Abstract

Objective

Depression and Chronic Low Back Pain (CLBP) are both frequent and commonly comorbid in older adults seeking primary care. Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) such as venlafaxine may be effective in treating comorbid depression and CLBP. For patients with comorbid depression and CLBP, our goal was to identify “easy-to-use” early clinical variables associated with response to 6 weeks of low-dose venlafaxine pharmacotherapy that could be used to construct a clinically-useful predictive model in future studies.

Methods

We report data from the first 140 patients completing phase 1 of the ADAPT clinical trial. Patients aged ≥60 with concurrent depression and CLBP received 6-weeks of open-label venlafaxine 150mg/day and supportive management. Using univariate and multivariate methods, we examined a variety of clinical predictors and their association with response to both depression and CLBP; change in depression; and change in pain scores at 6 weeks.

Results

26.4% of patients responded for both depression and pain with venlafaxine. Early improvement in pain at 2 weeks predicted improved response rates (p=0.027). Similarly, positive changes in depression and pain at 2 weeks independently predicted continued improvement at 6 weeks in depression and pain, respectively (p<0.001).

Conclusions

An important minority of patients benefitted from 6 weeks of venlafaxine 150mg/day. Early improvement in depression and pain at 2 weeks may predict continued improvement at week 6. Future studies must examine whether patients who have a poor initial response may benefit from increasing the SNRI dose, switching, or augmenting with other treatments after 2 weeks of pharmacotherapy.

Keywords: Primary Care, Back Pain, Depression, Geriatrics, Venlafaxine, Predictors of Response, Clinical Trial

Introduction

Depression and chronic low back pain (CLBP) are common in older adults treated in primary care, with point prevalence rates approaching 12% for both conditions (1, 2). In late-life, these conditions are frequently co-morbid, sharing risk factors, a linked biology, and overlapping psychological signatures (3, 4). Levels of depression have been found to be higher in CLBP than in other common pain syndromes in late-life (e.g., knee osteoarthritis) (5). Furthermore, CLBP and depression, especially when comorbid, increase the risk of other medical conditions and negative outcomes, such as falls and drug interactions (6).

There is an emerging body of evidence suggesting that treatment of CLBP can improve depressive symptoms and vice versa (7, 8). Because of an aging population in North America, research into parsimonious treatment strategies that simultaneously target both conditions is necessary to minimize polypharmacy and optimize outcomes. Linking depression treatment with care of physical conditions such as CLBP also may decrease the stigma of receiving treatment for a psychiatric condition, improving both adherence and clinical outcomes (9). Identifying predictors of early response for both depression and CLBP may help limit unnecessarily long pharmacotherapy attempts in patients with probable future non-response so often encountered in comorbid depression and medical conditions (10). Providing primary care physicians (PCPs) with simple predictors of early response for these linked conditions is important since they deliver 50% of all mental health care in the United States (11) and are the first-line providers for older adults living with comorbid depression and CLBP (1, 12).

Since PCPs have heavy patient loads and usually lack specialized training in mental health (11), pharmacotherapy treatment strategies for older adults living with comorbid depression and CLBP are especially attractive. Given the multifactorial nature of CLBP in older adults, which often includes a neuropathic etiology (3, 13), and the fact that many of these patients have not responded to first-line treatment with a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI), a Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor (SNRI) may be a more suitable choice for antidepressant and analgesic pharmacotherapy. Indeed there are data supporting the use of SNRIs and tricyclics in patients living with comorbid depression and chronic pain (14–16). For example, our group observed that in a 12-week open-label trial, duloxetine was effective in treating comorbid depression and CLBP in late-life (15). This finding was replicated in a 16-week randomized controlled trial (14). PCPs need to know the characteristics of early response to SNRI pharmacotherapy.

Using data from an open-label clinical trial using lower-dose venlafaxine for older adults with CLBP and depression (up to 150 mg/day), we explored easy-to-use potential predictors of response for both mood and low back pain at six weeks. Our goal was to identify early predictors of those who will respond to 6 weeks of treatment with this attractive and straightforward primary care approach, which would allow the construction of definitive clinically-useful predictive models in future studies.

Methods

We examined data from Phase 1 of the Addressing Depression and Pain Together (ADAPT) study (17). ADAPT is an ongoing NIH-funded clinical trial (NCTO1124188) testing a stepped-care approach for older adults living with comorbid depression and CLBP. The study has been approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and all participants provided signed informed consent.

Patient Population and Recruitment Procedures

Participants were aged ≥60, had a Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) (18) diagnosis of a depressive syndrome (major depression, minor depression, dysthymia), and a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) score ≥10 (19), consistent with at least moderate depression severity, the patient population recommended by the McArthur Guidelines to receive depression treatment in primary care (20). Participants also identified CLBP as their primary pain problem, a history of failed treatments for CLBP (e.g., oral or topical analgesics, physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, surgery, injections), and a Numeric Rating Scale for lower back pain (NRS) severity rating of ≥ 8 (theoretical range 0–20). The NRS is a validated scale that assesses average lower back pain intensity over the past week and is a preferred scale to demonstrate pain intensity in older adults (21). Using a 0–20 range was found to be more useful in older adults than a 0–10 scale (21)

We excluded subjects with the following problems: unstable medical conditions; substance use disorders; dementia; psychotic disorders; bipolar disorder; those who were wheelchair bound; or those involved in legal action related to low back pain. We did not exclude subjects with fibromyalgia or neuropathic pain because these conditions are common in older adults (13) and are sometimes responsive to antidepressant treatment (17). Patients were recruited from PCP practice settings in the Pittsburgh metropolitan area, research registries, and on-air and print advertisements. The recruitment strategies and participant entry criteria are described in further detail elsewhere (17).

Study Intervention

In phase 1 of ADAPT, all patients received 6 weeks of open-label treatment with venlafaxine and 30-minute weekly supportive management sessions which promoted adherence, assessed and managed treatment-emergent side effects, and monitored concerns of safety and suicidality. Venlafaxine was increased up to 150mg/day (or the highest tolerated dose) in the first 9 days and maintained at that level for the remainder of the 6-week trial. If a participant was taking another antidepressant, this was discontinued before starting venlafaxine. In order to be representative of usual practice and to minimize the chance of worsening symptoms and emerging suicidality, there was no “washout” period. Participants were permitted to remain on currently prescribed doses of analgesics and other pain treatments (e.g., stably attended physical therapy) for the duration of the study.

Outcomes

Our primary dichotomous outcome was clinical response in both depression and pain at 6 weeks. Based on previous work in this field (17), we defined response as PHQ-9 ≤5 (22) and ≥30% improvement on the NRS for low back pain (23). PHQ-9 and NRS had been measured every week. For response, we required that both the depression and pain criteria be met for two consecutive weeks (17).

Our secondary continuous outcomes were changes in depression (PHQ-9) and low back pain (NRS) scores at 6 weeks. We chose these scales because of their user-friendliness and potential ease of implementation in primary care settings. 6-week outcome was chosen because 1) this is consistent with the duration of time depressed patients are usually exposed to antidepressant during the acute phase of treatment; 2) because we have observed that if low back pain is going to respond to antidepressant pharmacotherapy, it usually does so by around week 2 (15), and 3) because 6 week is a reasonable surrogate marker for long-term improvement at 12-week and 1-year follow-up: i.e. if someone has not responded by 6 weeks, they are very unlikely to respond at later time points (24–26).

“Easy-to-Use” Predictor Variables

Our predictor variables were clinical questionnaires and tools that would be easy to administer at baseline and at two weeks in PCP settings, with a track-record of being well-tolerated in these settings: Baseline PHQ-9; Change in PHQ-9 at 2 weeks; Baseline NRS; Change in NRS at 2-weeks; Baseline Pain Map score (a self-report map of the human body, where patients indicate the location(s) pain is experienced, scored from 0–45) (27); Patient Global Impression of Change (PGI-C) at 2 weeks; Baseline Brief Symptom Inventory - Anxiety (28); and the diagnosis of fibromyalgia at baseline (29). We also chose three single-question items that could be easily asked prior to treatment that may be associated with both depression and CLBP response: Previous back surgery; Pain interfering with Sleep; and Pain radiating below the knee (30). Two-week change in NRS and PHQ-9 were chosen as variables because of recent evidence that 2-week SNRI antidepressant response is predictive of 12-week improvement in late-life depression (31): We tested whether the same principle applied to pain/depression response with low-dose venlafaxine.

Data Analysis

Baseline descriptive statistics (%(n), mean, median, standard deviation) were generated to characterize the study population, including demographics, PRIME-MD psychiatric diagnoses, and our 11 predictor variables. We then assessed associations of the primary and secondary outcomes with our predictor variables. For these analyses, chi-squared testing and bivariate correlational analyses were used as appropriate. For the bivariate correlational analyses, the Shapiro-Wilk Test were first used to assess whether continuous variables fit a normal distribution, thereby allowing us to decide between parametric (Pearson’s) and non-parametric (Spearman’s) analyses. If a predictor variable had a significant association with our outcomes on bivariate statistical testing, this variable was included in subsequent multivariate analyses. We conducted three multivariate analyses: a logistic regression with “response to both pain/depression at 6-week follow-up” as dependent variable and two multiple linear regression analyses using the dependent variables 6-week change in NRS and 6-week change in PHQ-9, respectively. Similar analytic approaches having been used when examining early predictors of depression response (31). We chose to analyze Phase 1 completers because 6-week data was available for these patients and we were most interested in early predictors of response/improvement in depression and CLBP at 6 weeks.

Analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 statistical software (IBM, Chicago, IL) and G*Power 3.13 (Universitat Kiel, Germany).

Results

Of the 174 participants recruited into the ADAPT project as of October 15th, 2013, 140 participants completed phase 1. The 34 non-completers either withdrew consent (16), developed possible medication side effects (7), terminated due to treatment-related issues (8), or had new unrelated medical problems (3). With regards to baseline characteristics, phase 1 non-completers but did not differ from completers. The baseline characteristics for completers are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics for Phase 1 Completers (n=140)

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median | Theoretical Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Mean Age (years) | 70.6 (± 8.4) | 68.5 | >60 |

| %Male | 38.6% (n=54) | - | - |

| %Caucasian | 83.6% (n=117) | - | - |

| PRIME-MD Depression and Anxiety Diagnoses (%, n) | |||

| Major Depression | 88.6% (n=124) | - | - |

| Minor Depression | 22.9% (n=32) | - | - |

| Dysthymia | 7.9% (n=11) | - | - |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 34.2% (n=48) | - | - |

| Panic Disorder (PD) | 14.2% (n=10) | - | - |

| Other Anxiety Disorders* | 22.9% (n=32) | - | - |

| Baseline Pain and Depression Scores | |||

| PHQ-9 (Depression) | 16.0 (4.2) | 16 | 0–27 |

| NRS (Pain) | 11.8 (3.1) | 11.5 | 0–20 |

| Other Baseline Clinical Descriptors | |||

| Meets ACR criteria for Fibromyalgia | 30.7% (n=43) | - | - |

| Previous Back Surgery | 34.3% (n=48) | - | - |

| Pain Interferes with Sleep | 78.1% (n=107) | - | - |

| Has Pain Below the Knee | 67.4% (n=93) | - | - |

| Pain Map Score | 13.0 (8.5) | 10 | 0–45 |

| Brief Symptom Inventory - Anxiety (BSI) | 1.01 (0.81) | 1 | 0–4 |

| Use of Non-Opioid Analgesics | 63.5% (n=89) | - | - |

| Use of Opioid Analgesics on a Regular basis | 20.7% (n=29) | - | - |

Other Anxiety Disorders includes: Panic Attacks or Agoraphobia Not Meeting Criteria for Panic Disorder Social Phobia; Obsessions; Compulsions; Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder; Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Of the 140 completers, 37 (26.4%) met criteria for response for both depression and CLBP. When considering the depression and pain response criteria separately at 6 weeks, 43.6% (61/140) had a ≥30% improvement on the NRS for low back pain, while 32.1% (45/140) achieved a PHQ-9 ≤5. Over 6 weeks, the mean decrease in PHQ-9 was 7.0 (±5.3), while the NRS decreased by 3.0 (±4.8).

Between our main outcome (response for both CLBP and depression) and the predictor variables, five univariate associations were found: Baseline Fibromyalgia was associated with reduced likelihood of response (OR=0.33, p=0.019), as was higher Baseline BSI-Anxiety (rho=−0.22, p=0.008), a higher Pain Map Score (rho=−0.25, p=0.003), a higher Baseline PHQ-9 (rho= −0.27, p=0.001), and a lower two-week change in NRS (rho= −0.18, p=0.034). In logistic regression (including all 5 variables), though, only two-week change in NRS independently predicted clinical response: OR=0.89 per point decrease in NRS at 2 weeks, p=0.027. (Overall R2 for the model=0.23) (table 2). The sensitivity and specificity of the logistic regression model was 27.0% (10/37) and 88.8% (87/98), respectively. The logistic regression model accurately predicted 27.0% of responders and 88.8% of non-responders, successfully predicting 71.5% of outcomes overall. Based on chance, we would have expected successful predictions in only 61% of outcomes overall.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Model with “Response in Both Depression and Pain at 6 weeks” as Dependent Variable (n=140)

| Predictor | B | SE B | Odds Ratio for Responding to both Depression and Pain at 6 weeks | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibromyalgia | −0.51 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.38 |

| Baseline BSI | −0.38 | 0.31 | 0.68 | 0.22 |

| Pain Map Score | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.96 | 0.19 |

| Baseline PHQ-9 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.91 | 0.12 |

| 2-week Change in NRS | −0.11 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 0.027 |

Nagelkerke R2 = 0.23

For our secondary outcome of depression, greater change in PHQ-9 at 2 weeks was associated with a greater degree of change in PHQ-9 by 6 weeks (univariate r=0.51, p<0.001), as was a greater week-2 change in PGI-C (rho=0.24, p=0.014). In multiple linear regression using these 2 variables, 2-week change in PHQ-9 was independently and positively associated with 6-week change in PHQ-9 (Beta=0.49, p<0.001), while PGI-C was not (p=0.75) (overall R2=0.23 for model). Thus, for each 1-point increase on 2-week change in PHQ-9, the 6-week change in PHQ-9 rose by .49 points.

For pain, the baseline PHQ-9 (rho=0.16, p=0.062) and the 2-week Change in NRS (rho=0.41, p<0.001) were correlated with 6-week Change in NRS. Baseline PHQ-9 (Beta=0.15, p=0.022) and 2-week Change in NRS (Beta=0.46, p<0.001) were both independently and positively associated with change in NRS at 6 weeks (R2=0.26 for 2-variable multiple linear regression model).

At our sample size (n=140), using a two-tailed alpha of 0.05 and power (1−β)=80%, we were able to detect small-moderate effect sizes and higher (OR<0.60 (dichotomous variable in logistic regression with 5 predictor variables), f2>0.06 (multiple regression with 2 predictor variables), ρ >0.23 (univariate regression/bivariate correlation).

Since 2-week change in PHQ-9 and NRS were correlated with 6-week change in PHQ-9 and NRS, respectively, we explored whether this association would be stronger if change at 3-, 4-, or 5-week follow-up were used. Although 5-week change in NRS/PHQ-9 appeared to most predictive (multivariate beta = 0.61 and 0.58 for NRS and PHQ-9, respectively), the predictive value at 2 weeks appeared to be comparable to those found at 3 weeks (PHQ-9 and NRS) and 4-weeks (PHQ-9) (tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Strength of association between change in NRS at week “n” and 6-week change in NRS

| Univariate | Multivariate (after controlling for Baseline PHQ-9) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2-week change in NRS | Beta=0.47, p<0.001 | Beta=0.44, p<0.001 |

| 3-week change in NRS | Beta=0.41, p<0.001 | Beta=0.38, p<0.001 |

| 4-week change in NRS | Beta=0.57, p<0.001 | Beta=0.55, p<0.001 |

| 5-week change in NRS | Beta=0.64, p<0.001 | Beta=0.61, p<0.001 |

Table 4.

Strength of association between change in PHQ-9 at week “n” and 6-week change in PHQ-9

| Univariate | Multivariate (after controlling for 2-week PGI-C) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2-week change in PHQ-9 | Beta=0.46, p<0.001 | Beta=0.49, p<0.001 |

| 3-week change in PHQ-9 | Beta=0.47, p<0.001 | Beta=0.44, p<0.001 |

| 4-week change in PHQ-9 | Beta=0.47, p<0.001 | Beta=0.45, p<0.001 |

| 5-week change in PHQ-9 | Beta=0.60, p<0.001 | Beta=0.58, p<0.001 |

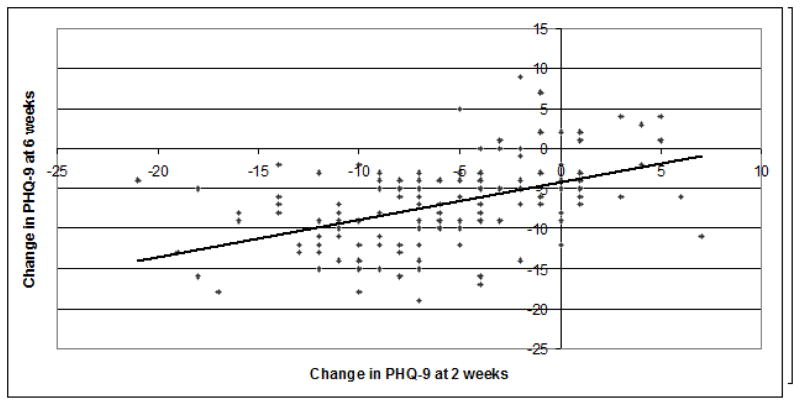

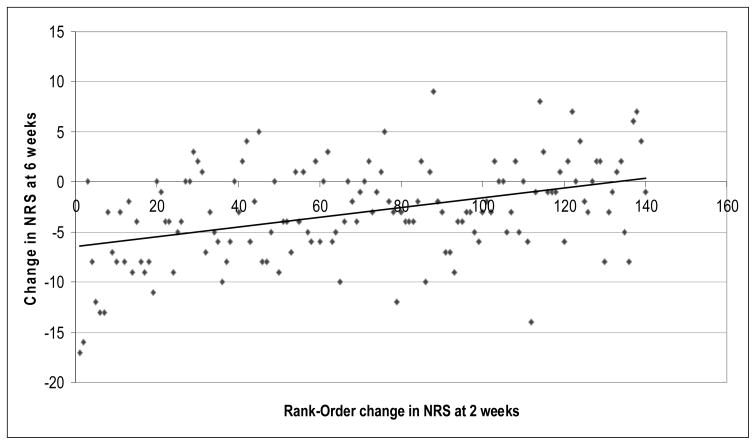

For the purposes of illustration, we have included simple bivariate scatter-plots for our two secondary outcomes with 2-week change in PHQ-9 and NRS, respectively (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Change in PHQ-9 at 2 weeks as a Predictor of Change in PHQ-9 at 6 weeks (n=140)

Univariate Pearson Correlation: r=0.51, p<0.001

This figure illustrates the correlation between Change in PHQ-9 at 2 weeks and Change in PHQ-9 at 6 weeks.

Figure 2.

Change in NRS at 2 weeks as a Predictor of Change in NRS at 6 weeks (n=140)

Univariate Spearman Correlation: rho=0.41, p<0.001

This figure illustrates the non-parametric (spearman) correlation between Change in NRS at 2 weeks and Change in NRS at 6 weeks.

Rank-Order Change in NRS at 2 weeks was computed by ordering values of “Change in NRS at 2 weeks” in ascending order (1–140). The largest “changes in NRS at 2 week” values had the highest numbers for rank-order change (e.g. 140).

Discussion

In this study, a substantial fraction of participants (26.4%) showed a response in terms of both depression and CLBP after 6 weeks open-label venlafaxine and supportive management. When each outcome is considered separately, 43.6% and 32.1% responded to pain and to depression, respectively. These figures are lower than a 12-week study of duloxetine 120mg/day in older adults, with approximately 50% responding to both pain and depression (15). Given that all patients in the current study previously failed CLBP treatment(s) and were exposed to low-dose venlafaxine for only 6 weeks, we are still impressed by this level of treatment response.

We found that patients with improvement in pain at 2 weeks were more likely to achieve response to both depression and pain after 6 weeks of venlafaxine 150mg/day. Although our logistic regression model (Table 2) was not very predictive of identifying responders (27.0%), it was able to predict non-responders with reasonable accuracy (88.8%) for response to both depression and pain at 6 weeks. One consequence of this is the following: if a patient had no improvement in pain in the first 2 weeks, we could be fairly confident that subsequent response would be unlikely.

Baseline low back pain (NRS) or depression (PHQ-9) severity, though, did not predict response at 6 weeks - i.e. regardless of pre-morbid pain or depression scores, patients appeared to have similar rates of response to both pain and depression. Our study only included patients with unsuccessful past pain treatments who reported both moderate-severe current pain and depressive symptoms. Given that less than half of patients respond to both CLBP and depression after 12 weeks of high-dose SNRI treatment (15), it is impressive that 26.4% of patients responded in our 6-week trial. This suggests that low-dose venlafaxine 150mg/day may be an effective therapeutic strategy in an important minority of CLBP/depression patients, irrespective of their pre-morbid pain and depression severity.

Perhaps our most exciting finding is that the change in PHQ-9 and NRS scores in the first two weeks of treatment correlated positively with 6-week change in PHQ-9 and NRS, respectively. Furthermore, the association between change at 2-weeks and 6-week change was comparable to those found at 3 weeks (for both PHQ-9 and NRS) and 4-weeks (for PHQ-9). This has direct implications to the clinical management of older depressed CLBP patients in primary care. Our data suggests that PCPs can feel more confident that what they are observing is progress for their patients when they see an early improvement in either pain or depression. If venlafaxine prescribed at 150 mg/day does not lead to a response for either low back pain or depression by week two of treatment, there is less likely to be subsequent response with another month of exposure to this dose of venlafaxine. We must caution, though, that patients have variability in their outcome, these are exploratory results, and the correlation between 2 and 6 week improvement is by no means perfect. Two-week change in NRS and PHQ-9 explained 21 and 25% of the variance in 6-week change, meaning that additional, less “easy-to-use” clinical variables may be necessary to predict more of the variation in depression and pain outcome.

With regards to pain, but not depression, our findings are consistent with previous SNRI studies in CLBP samples. As a group, patients’ pain often responded within the first two-weeks and frequently remained improved for the remainder of the treatment period (14, 15).

Also, we found that baseline PHQ-9 was positively correlated with 6-week change in NRS. Taken with our other findings, this means that while improvement in 2-week depression scores does not predict improvement in pain, patients who are initially more depressed may have equal or better pain response to venlafaxine. This contradicts previous evidence, which suggested that SNRI-treated patients with low baseline depressive symptoms improved the most (14, 15). In addition, two-week change in PHQ-9 did not appear to predict six-week change in NRS and vice versa, suggesting that a patient who presents primarily for CLBP and has an early improvement to their pain need not necessarily be discouraged if their depression has not changed in the same fashion. The evidence largely suggests that pain (32) and CLBP (3), in particular, have a bidirectional relationship with depression. It is possible that although pain and depressive response may not initially be synchronous (14), pain and depression severity generally move in the same direction in longer term follow-up (32).

Our findings have implications for future research. Past work has demonstrated that an adequate trial of antidepressant pharmacotherapy in late-life depression is 4 weeks: if there is no indication of improvement by 4 weeks, there is unlikely to be subsequent improvement (24). In the field of depression and CLBP, compared to switching from escitalopram to duloxetine at 8 weeks, switching at 4 weeks led to superior outcomes (14). No study to date has looked specifically at switching strategies when treating depression and CLBP exclusively with SNRIs. From our data, it appears that improvements in pain and depression can be detected as early as 2 weeks. Future studies could examine the clinical and cost-effectiveness outcomes of modifying low-dose SNRI therapy in “non-improvers” at 2 weeks. Potential approaches could include: increasing SNRI doses to higher levels (e.g. venlafaxine 225–300mg/day); switching to another SNRI or tricyclic antidepressant (e.g. duloxetine or nortriptyline); or augmenting with additional monoaminergic or analgesic medication, psychotherapy, or physiotherapy.

Limitations

Phase 1 of ADAPT involves open-label non-randomized treatment with venlafaxine without a control group, which makes it difficult to ascertain whether some patients had a placebo response. Our sample size limited our ability to detect all possible predictor variables, but with 140 participants we were still able to reliably detect correlations with small-moderate effect sizes. As well, even though patients in this study were treatment-refractory, with high rates of back surgery and most having previously seen a pain specialist, there remains some uncertainty as to whether some patients would have responded simply to supportive care alone. This is especially true since care management can affect depression and CLBP response (15). As well, we used PHQ-9 ≤5, a relatively rigorous threshold for depression response. For many patients, especially those with severe depression, change in PHQ-9 may be a more clinically important and achievable outcome in a short SNRI trial. As well, using detailed genetic, psychological, and physiological variables may have improved the potential predictive value of our statistical models, we did not include these since our main goal was to identify “easy-to-use” predictors that would be feasible in busy primary care settings. Additionally, since we used the same dataset for model building and accuracy testing, our stated accuracy of 71.5% may have been an overestimate. Lastly, although our current model predicted 88.8% of non-responders, it was only able to accurately predict 27.0% of responders. Consequently, future research will be required in order to construct definitive predictive models for clinical practice.

Conclusions

It is encouraging that a considerable number of patients benefitted from 6 weeks of open-label venlafaxine 150mg/day and supportive care, regardless of their initial severity of pain or depression. PCPs may also appreciate that depressive and pain outcome as early as 2 weeks may help predict whether patients will subsequently improve in these domains. This represents a significant deviation from current clinical practice: although adult depression guidelines suggest switching/adding agents if there is <20% improvement after 2 weeks (25), experts treating older adults with depression and CLBP suggest waiting at least 4–8 weeks prior to changing treatment (14). Future studies are needed to confirm whether patients with depression and CLBP who have a poor initial response to a low-dose SNRI may benefit from increasing the SNRI dose, switching, or augmenting with other treatments after 2 weeks of pharmacotherapy.

Footnotes

This manuscript has not been previously published or presented.

Conflicts of Interest:/Disclosures Summary:

This work was funded by grant AG033575 (Jordan Karp) and by grant KL2 RR024154 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Medications were provided by Pfizer for this investigator-initiated trial. Clinicaltrials.gov Trial Registration Identifier: NCT01124188. Soham Rej is funded by Master’s awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Federation de Recherche en Sante Quebec (FRSQ). Dr. Karp has received medication supplies for investigator-initiated research from Pfizer, and Reckitt Benckiser. Dr. Rej and Dr. Dew have no potential conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Lyness JM, Caine ED, King DA, Cox C, Yoediono Z. Psychiatric disorders in older primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(4):249–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP, Jackman AM, Darter JD, Wallace AS, et al. The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(3):251–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karp JF, Shega JW, Morone NE, Weiner DK. Advances in understanding the mechanisms and management of persistent pain in older adults. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(1):111–20. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellegaard H, Pedersen BD. Stress is dominant in patients with depression and chronic low back pain. A qualitative study of psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with non-specific low back pain of 3–12 months’ duration. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morone NE, Karp JF, Lynch CS, Bost JE, El Khoudary SR, Weiner DK. Impact of chronic musculoskeletal pathology on older adults: a study of differences between knee OA and low back pain. Pain Med. 2009;10(4):693–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee WK, Kong KA, Park H. Effect of Preexisting Musculoskeletal Diseases on the 1-Year Incidence of Fall-related Injuries. J Prev Med Public Health. 2012;45(5):283–90. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.5.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skolasky RL, Riley LH, 3rd, Maggard AM, Wegener ST. The relationship between pain and depressive symptoms after lumbar spine surgery. Pain. 2012;153(10):2092–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid MC, Otis J, Barry LC, Kerns RD. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain in older persons: a preliminary study. Pain medicine. 2003;4(3):223–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002;288(22):2836–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Lavori PW, Trivedi MH, Sackeim HA, et al. Sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25(1):119–42. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Triana AC, Olson MM, Trevino DB. A new paradigm for teaching behavior change: Implications for residency training in family medicine and psychiatry. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, Tang L, Williams JW, Jr, Kroenke K, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2003;290(18):2428–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiner DK. Office management of chronic pain in the elderly. Am J Med. 2007;120(4):306–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romera I, Perez V, Manuel Menchon J, Schacht A, Papen R, Neuhauser D, et al. Early vs. conventional switching of antidepressants in patients with MDD and moderate to severe pain: A double-blind randomized study. J Affect Disord. 2012;143(1–3):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karp JF, Weiner DK, Dew MA, Begley A, Miller MD, Reynolds CF., 3rd Duloxetine and care management treatment of older adults with comorbid major depressive disorder and chronic low back pain: results of an open-label pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(6):633–42. doi: 10.1002/gps.2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan MJ, Reesor K, Mikail S, Fisher R. The treatment of depression in chronic low back pain: review and recommendations. Pain. 1992;50(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90107-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karp JF, Rollman BL, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Morse JQ, Lotrich F, Mazumdar S, et al. Addressing both depression and pain in late life: the methodology of the ADAPT study. Pain Med. 2012;13(3):405–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01322.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. Jama. 1999;282(18):1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han C, Voils CI, Williams JW., Jr Uptake of Web-Based Clinical Resources from the MacArthur Initiative on Depression and Primary Care. Community Ment Health J. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herr KA, Spratt K, Mobily PR, Richardson G. Pain intensity assessment in older adults: use of experimental pain to compare psychometric properties and usability of selected pain scales with younger adults. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(4):207–19. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Wu J, Hoke S, Sutherland J, et al. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2009;301(20):2099–110. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrar JT, Portenoy RK, Berlin JA, Kinman JL, Strom BL. Defining the clinically important difference in pain outcome measures. Pain. 2000;88(3):287–94. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulsant BH, Houck PR, Gildengers AG, Andreescu C, Dew MA, Pollock BG, et al. What is the optimal duration of a short-term antidepressant trial when treating geriatric depression? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(2):113–20. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000204471.07214.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kennedy SH, Lam RW, Parikh SV, Patten SB, Ravindran AV. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. Introduction. Journal of affective disorders. 2009;117 (Suppl 1):S1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andreescu C, Mulsant BH, Houck PR, Whyte EM, Mazumdar S, Dombrovski AY, et al. Empirically derived decision trees for the treatment of late-life depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):855–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eggermont LH, Shmerling RH, Leveille SG. Tender point count, pain, and mobility in the older population: the mobilize Boston study. J Pain. 2010;11(1):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sayar K, Aksu G, Ak I, Tosun M. Venlafaxine treatment of fibromyalgia. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(11):1561–5. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costa Lda C, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Hancock MJ, Herbert RD, Refshauge KM, et al. Prognosis for patients with chronic low back pain: inception cohort study. Bmj. 2009;339:b3829. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joel I, Begley AE, Mulsant BH, Lenze EJ, Mazumdar S, Dew MA, et al. Dynamic Prediction of Treatment Response in Late-Life Depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, Wu J, Bair MJ, Krebs EE, Damush TM, Tu W. Reciprocal relationship between pain and depression: a 12-month longitudinal analysis in primary care. J Pain. 2011;12(9):964–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]