Abstract

The FERM domain protein Merlin, encoded by the NF2 tumor suppressor gene, regulates cell proliferation in response to adhesive signaling. The growth inhibitory function of Merlin is induced by intercellular adhesion and inactivated by joint integrin/receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Merlin contributes to the formation of cell junctions in polarized tissues, activates anti-mitogenic signaling at tight-junctions, and inhibits oncogenic gene expression. Thus, inactivation of Merlin causes uncontrolled mitogenic signaling and tumorigenesis. Merlin's predominant tumor suppressive functions are attributable to its control of oncogenic gene expression through regulation of Hippo signaling. Notably, Merlin translocates to the nucleus where it directly inhibits the CRL4DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase, thereby suppressing inhibition of the Lats kinases. A dichotomy in NF2 function has emerged whereby Merlin acts at the cell cortex to organize cell junctions and propagate anti-mitogenic signaling, whereas it inhibits oncogenic gene expression through the inhibition of CRL4DCAF1 and activation of Hippo signaling. The biochemical events underlying Merlin's normal function and tumor suppressive activity will be discussed in this Review, with emphasis on recent discoveries that have greatly influenced our understanding of Merlin biology.

Keywords: Merlin, NF2, Hippo signaling pathway, Contact inhibition, DCAF1, CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase

Introduction

The ability of normal cells to survive and proliferate is dictated by environmental cues, including intercellular and matrix adhesions as well as the presence of growth factors. Normal cells undergo growth arrest when detached from the extracellular matrix or when they come into contact with adjacent cells and form intercellular junctions [1]. Neoplastic cells evade contact inhibition of proliferation, which leads to the disruption of tissue organization - a distinguishing event in cancer [2]. The NF2 (Neurofibromatosis Type 2) tumor suppressor gene encodes the FERM (4.1 protein/Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin) domain protein Merlin, which is coordinately regulated by intercellular adhesion and attachment to the extracellular matrix [3-7]. Cadherin engagement inactivates PAK, causing an accumulation of the active, dephosphorylated form of Merlin. Notably, since integrin attachment to the extracellular matrix activates PAK, Merlin can therefore be regulated independently of contact-mediated signaling events [7].

Neurofibromatosis type 2 patients carry a single mutated NF2 allele and develop a highly specific subset of central and peripheral nervous system tumors. NF2-associated tumors include schwannomas, meningiomas, and ependymomas, which arise from the Schwann cells comprising the myelin sheath surrounding sensory and motor neurons, arachnoid cap cells within the arachnoid villi in the meninges, and ependymal cells lining the CSF-filled ventricles of the brain and central spinal canal, respectively. In addition to the autosomal dominant NF2 disorder, non-germline Merlin deficiency is a driving force in sporadic occurrences of nearly all vestibular schwannomas, a majority of meningiomas, and a notable fraction of ependymomas. Moreover, Merlin was found to be inactivated in a large proportion of malignant mesotheliomas [8,9] and to a lesser extent in other solid tumors [10-13].

Due in large part to Merlin's high sequence homology to the ERM (Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin) family of cytoskeletal linker proteins, it was widely assumed that Merlin suppresses mitogenic signaling at the cell cortex to mediate contact inhibition and tumor suppression [14]. Active Merlin suppresses Rac-PAK signaling [7,15-17], restrains activation of mTORC1 independently of Akt [18,19], inhibits PI3K-Akt and FAK-Src signaling [20,21], and negatively regulates the EGFR-Ras-ERK pathway [22,23]. However, the mechanisms by which Merlin inhibits these pathways remain unclear, and furthermore, the relative contribution of these pro-mitogenic signals to various Merlin-deficient malignancies is unknown. Interestingly, Merlin activates the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway to suppress the transcriptional coactivators YAP/TAZ in mammals or the Drosophila ortholog Yorkie, revealing a conserved role for Merlin in regulation of organ size, stem cell behavior, and cell proliferation [24-26]. Notably, few germline or somatic mutations of Hippo pathway components have been discovered in human tumors - the exception being Merlin, which remains as one of the only bona fide tumor suppressors in the Hippo pathway.

Merlin's upstream regulation has been extensively characterized, and recently reported models of regulation and post-translational modification will be highlighted in this Review. Post-translational modification of Merlin is vitally important to its conversion between dormant and growth-inhibitory states, where the dephosphorylated and more open state is now considered to be active in contact inhibition and tumor suppression [27]. However, without crystallographic analyses of full-length Merlin in both its active and inactive conformations, structural inferences drawn from biochemical experiments must be approached with caution. Apropos of the myriad upstream signals and modifications affecting Merlin, the downstream biochemical functions of Merlin have been the subject of intensive research for two decades, yet a consensus mechanism for Merlin's function in normal tissues has not been reached. It is becoming apparent that Merlin functions primarily in two branches – contact inhibition of proliferation and tumor suppression. Although these branches are naturally intertwined, the distinct locations of Merlin function and respective interactors in those subcellular compartments lend credence to a concept of a bimodal function.

Recent studies among the ever-increasing breadth of NF2 literature have revealed important high-affinity interactors governing Merlin's biochemical function. Notably, Merlin regulates tight junction-associated Angiomotin to inhibit Rac signaling [28], and nuclear-localized Merlin inhibits the CRL4DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase to suppress oncogenic gene expression [29]. Moreover, Merlin's regulation of YAP/TAZ is a burgeoning and highly provocative field due to the multifarious roles of Hippo signaling in organ growth, stem cell maintenance, and cancer. Recent studies have also shed light on Merlin's conformational changes that regulate its intramolecular associations and downstream signaling, providing fundamental insight into Merlin's regulation and biochemical function. In this Review, we will explore Merlin's rich biochemical background and examine new insights that are shaping our understanding of Merlin's role in normal biology and how its loss leads to the deregulation of a multitude of signaling pathways leading to tumorigenesis.

The NF2 gene

NF2 maps to the long arm of chromosome 22 and encodes two Merlin isoforms. The longer, dominant Merlin isoform 1 (Merlin-1 or Merlin), has an extended carboxy-terminal tail that is encoded by exon 17 (Fig. 1A). Merlin isoform 2 (Merlin-2), on the other hand, contains the alternatively spliced exon 16 which ends in a stop codon, encoding 11 unique residues following amino acid 579 as compared to Merlin-1 [10]. Notably, Merlin-2 lacks carboxy-terminal residues required for intramolecular binding between the amino-terminal FERM domain and the carboxy-terminal tail, possibly leading to a constitutively open conformation [30,31]. Recent studies have found that Merlin-2 inhibits cell proliferation and attenuates downstream mitogenic signaling to the same extent as Merlin-1 [27,32].

Figure 1.

(A) Merlin structure and overview of pathogenic mutations. Merlin is a 595-residue protein divided into three structurally distinct regions – an amino-terminal FERM domain, an α-helical coiled-coil domain, and a carboxy-terminal hydrophilic tail. Merlin's FERM domain is further subdivided into three globular subdomains. Nf2 encodes 16 exons, terminating with exon 17 in the canonical Merlin isoform. The positions of patient-derived missense mutations or single residue deletions are indicated below the exon schematic, with mutation frequency indicated by a heat map. Either these mutations underlie NF2 tracked within a family, were found in two or more unrelated patients, or experimental evidence was obtained to confirm their pathogenicity. Mutational data were obtained from Ahronowitz et al, 2007 [48] and Li et al, 2010 [29]. (B) Adhesion-mediated regulation of the Merlin activation cycle. (Left) In contact-inhibited cells, dephosphorylated Merlin accumulates as a result of intercellular adhesions which lead to PAK inhibition. Merlin may also be activated via MYPT1-mediated dephosphorylation. (Right) Conversely, in proliferating cells, integrin-mediated anchorage to the cell matrix and stimulation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) activate Rac, in turn activating PAK and leading to phosphorylation of Merlin at Serine 518. In response to high cyclic AMP levels, PKA also phosphorylates Merlin at serine 518. Serine 518 phosphorylation increases the interdomain binding between Merlin's carboxy-terminus and FERM domain, maintaining Merlin in a more closed, inactive form.

Merlin protein structure and intramolecular association

The biochemical functions of Merlin are imparted by three mechanisms - post-translational modification, localization, and interaction with downstream effectors. Merlin is composed of a globular amino-terminal FERM domain and a carboxy-terminal hydrophilic tail joined by a flexible coiled-coil segment, displaying structural resemblance to the FERM domain-containing ERM proteins (Fig. 1A) [33,34]. This resemblance is most apparent in the first 300 residues of Merlin's FERM domain, which share ∼65% sequence identity with canonical ERMs. However, Merlin has several notable differences in its primary sequence that distinguish it in form and function from its ERM counterparts. Merlin's amino-terminus contains a 7-residue conserved Blue box motif and 17 unique amino-terminal residues [35,36]. Importantly, Merlin lacks a canonical actin-binding motif that is otherwise conserved among ERMs and paramount to their function at the cortical cytoskeleton [14].

A central mechanism in Merlin and ERM function is the formation of homo- and heterotypic interactions that regulate their activity. The majority of ERMs within cells are held in a dormant state imparted by an intramolecular association between the FERM domain and the C-terminal tail [37-39]. Disruption of this association and subsequent activation is achieved by phosphorylation of an ERM C-terminal threonine residue by Rho kinase. Active ERMs bind to cytoplasmic domains of cell-adhesion receptors such as CD44 and ICAM via their FERM domains while their C-termini interact with and regulate the cortical actin cytoskeleton [40,41]. Furthermore, once opened, active ERM proteins may form interactions amongst themselves and with Merlin [37]. Merlin's intramolecular associations and subsequent activation states have been a subject of intensive study for nearly 20 years [27,30,31,38,42-44], yet a consensus model to explain the relationship between its phosphorylation and interdomain binding in the context of seemingly contrary genetic evidence has only recently been uncovered.

It is well established that Merlin switches from an active state to an inactive state by phosphorylation at serine 518 (Fig. 1B) [45]. Phospho-mimetic (S518D) or phospho-deficient (S518A) permutations strongly correlate with Merlin's growth-permissive or growth-inhibitory functions, respectively [27,29,46]. Essentially, serine 518 phosphorylation acts as a binary switch in which dephosphorylated Merlin functions in adhesion signaling while phosphorylated Merlin remains dormant, although studies within the last five years have shown this to be an oversimplified interpretation. Several lines of evidence suggest that Merlin exists in multiple states that vary between “fully open” and “fully closed” forms which are regulated primarily by S518 phosphorylation, and moreover, FRET studies reveal that Merlin's FERM domain and carboxy-terminus are constitutively held in close proximity, undergoing only subtle changes upon post-translational modification [27,47]. A classic study found that Merlin-2 – which lacks the carboxy-terminal residues necessary for intramolecular interaction - is unable to function in contact inhibition or tumor suppression [30]. This observation led to a hypothesis that was held for over a decade positing that dephosphorylated and active Merlin functions in a closed conformation.

Recently, two independent laboratories found that Merlin-2 suppresses growth in mammalian cell lines, suggesting that interdomain binding is dispensable for Merlin's adhesion signaling [27,32]. Through comprehensive biochemical investigation, Anthony Bretscher's group reported that phosphorylated Merlin displays higher interdomain binding and that Merlin therefore inhibits cell growth in its open state [27]. These results are underscored by the observation that a stably closed Merlin mutant does not suppress cell growth, whereas Merlin-2 and the S518A mutant -which are both defective in interdomain binding and therefore more open - suppress growth to the same extent as wild-type Merlin. Cumulatively, these results reveal that S518 phosphorylation and mutations that cause Merlin to become more closed result in decreased growth inhibition, whereas more open forms of Merlin - those that are increasingly defective in interdomain binding - are more active in growth inhibition. This finding contributes greatly to a consensus of Merlin structure and function as it relates to normal biology and tumor suppression, resolving a decade-old schism between biochemical observations and in vivo genetic studies.

Biochemical studies have provided essential insight into Merlin's conformational changes and resulting activation, which are now largely corroborated by genetic data. Most patient-derived truncations and a vast majority of non-truncating mutations occur within the FERM domain (Fig. 1A), lending credence to its quintessential role in anti-mitogenic signaling and tumor suppression [48]. Initially discovered in Drosophila, the “Blue box motif” is a conserved region within the FERM subdomain F2 corresponding to residues 177-183 in human Merlin. Substitution of these residues with alanines imparts loss of contact inhibition and promotes tumorigenesis in NIH-3T3 cells [49]. Mutations in the Blue box act in a dominant negative manner in both Drosophila and mammals, displaying the importance of the FERM domain in Merlin's tumor suppressive function. As compared to the FERM domain, mutations are scarce in Merlin's carboxy-terminal tail and are dramatically reduced in the central α-helical domain, again implying that Merlin's downstream tumor suppressive functions a re imposed by the FERM domain (Fig. 1A) [48]. Notably, replacement of Merlin's F2 subdomain with that of the ERM protein Ezrin abolishes its growth suppressive activity, while individual or combined replacement of subdomains F1 and F3 do not affect proliferation [32]. These results imply that subdomain F2 of Merlin's FERM domain is largely responsible for Merlin's growth inhibitory effects. Truncating mutations correlate with increased NF2 severity and predominate among NF2 patients, while missense mutations - although more rare - allow for a more systematic interpretation of Merlin's biochemical role in tumor suppression. Merlin's FERM domain interacts directly with the CRL4DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase inhibiting its ubiquitination activity and downstream oncogenic signaling. Multiple patient-derived missense mutants, including those mapping to subdomain F2, are defective in CRL4DCAF1 interaction, despite the fact that some of these mutations were predicted to cause little structural perturbation [29,34].

Recent biochemical insights combined with more than a decade of patient-derived genetic data provide crucial insight into Merlin's normal biochemical function and role in tumor suppression. Merlin's α-helical domain and carboxy-terminus function in maintaining Merlin in an inactive conformation during normal biological function, and may further be necessary for functions underneath the cell cortex in the organization of cell junctions and in contact inhibition. However, while interdomain binding is an important part of Merlin's regulation and normal cellular functions, the overall structure and specific protein-interacting domains within Merlin's amino-terminal FERM domain are essential for contact inhibition and tumor suppression.

Post-Translational Modification of Merlin

Merlin is regulated by multiple post-translational modifications downstream of an ever-expanding array of intracellular and extracellular cues. Receptor tyrosine kinases and integrins relay pro-mitogenic signals by activating CDC42 and Rac, which in turn activate p21-activated kinase (PAK) (Fig. 1B). Activated PAK directly phosphorylates Merlin at serine 518, leading to an increase in carboxy-terminal association with the FERM domain and subsequent inactivation, presumably through masking of protein-interacting domains on the FERM domain which are necessary for downstream signaling or occlusion of a nuclear localization signal [29,33]. Since Merlin has a long half-life within cells, it is a compelling hypothesis that phosphatases exist to dephosphorylate Merlin at serine 518 and dynamically control levels of the dephosphorylated active form. MYPT1-PP1δ (MYPT1) is a phosphatase that was shown to dephosphorylate Merlin [22] (Fig. 1B), and recent evidence revealed that it may be inhibited by Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) [50]. It remains to be determined whether MYPT1-mediated Merlin activation via dephosphorylation is a major mechanism in NF2 pathogenesis and Merlin-deficient tumors, or whether nascent and dephosphorylated Merlin largely functions in this capacity.

The phosphorylation status of serine 518 drives Merlin's activation cycle, although other modifications modulate Merlin's conformation and downstream biochemical functions. Phospho-peptide mapping and band-shift experiments revealed that Merlin is phosphorylated at multiple sites and that serine 518 phosphorylation may be necessary for subsequent phosphorylation at other residues [51,52]. In addition to PAK-mediated phosphorylation, PKA was shown to independently phosphorylate Merlin at serine 518 and serine 10, the latter modification affecting the actin cytoskeleton [53,54]. Merlin's phosphoregulation by PKA may be an important mechanism in cells which are sensitive to the cyclic AMP-PKA signaling axis, including the pathogenically relevant Schwann cells [55]. AKT phosphorylates Merlin at two additional sites -threonine 230 and serine 315 – and this phosphorylation causes decreased interdomain binding, intermolecular binding to phosphoinositides and PIKE-L (a GTPase that enhances PI3K activity), and ubiquitination [56]. The observation that AKT-mediated phosphorylation blocks Merlin's interaction with PIKE-L supports an inhibitory role for this interaction [20,56]. This finding also raises the possibility that constitutive activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway resulting from PTEN loss or activating PI3K mutations would lead to Merlin inactivation, imparting a PI3K feed-forward mechanism. However, speculation that Merlin is inactivated by decreased interdomain binding conflicts with the recent observations that the open form of Merlin is active [27,32]. Moreover, the importance of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in Merlin's degradation is debatable, as cycloheximide chase experiments revealed that Merlin has a half-life exceeding 24 hours [29], although this does not rule out other ubiquitination-mediated effects on Merlin function. Akt- and PAK-mediated phosphorylation of Merlin was recently shown to promote its sumoylation - an ubiquitin-like modification - which was found to affect Merlin's subcellular localization, interdomain binding, and growth-inhibitory activity [57]. However, the requirement for sumoylation in Merlin's normal function and in tumor suppression remains incompletely understood since'serine 518 phosphorylation, which renders Merlin inactive, appears to promote its sumoylation.

Merlin Localization and Function

Functions at the Plasma Membrane, Cell Cortex, and Cytoskeleton

As cells become confluent, Merlin interacts with membrane-associated proteins where it regulates the formation of membrane domains [58]. Merlin's organization of intercellular contacts is central to its normal function in contact inhibition, which is disrupted in Merlin-deficient tissues [59]. Indeed, Merlin was initially interpreted as functioning at the cell cortex due to its homology to ERM proteins and its localization by immunostaining [60]. This notion was supported in Drosophila by the observation that nascent Merlin is recruited to the plasma membrane [36,61]. These observations were corroborated by Merlin's role in the establishment of adherens junctions in confluent cells and localization in lamellipodia and membrane ruffles [5,7,62-64]. Merlin interacts with a number of proteins that are localized at or underneath the plasma membrane, including other ERMs, NHERF, the intracellular domain of CD44, α-catenin at maturing adherens junctions, and Angiomotin at tight junctions [6,28,59,60,65].

In keratinocytes and skin epithelium, Merlin is recruited to α-catenin and promotes its binding to Par3, aiding in the maturation of adherens junctions (Fig. 2A) [59]. This is consistent with the disruption of adherens junctions in Merlin-deficient primary fibroblasts and keratinocytes [5]. Interestingly, α-catenin can bind to 14-3-3 protein, which sequesters phosphorylated YAP in the cytoplasm and suppresses YAP-mediated transcription [66,67]. Moreover, it was recently discovered that α-catenin interacts with the APC tumor suppressor to promote the ubiquitination and degradation of β-catenin as well as repression of Wnt target genes in the nucleus [68]. Since Merlin's interaction with α-catenin and its role in junction formation was exclusively studied in skin and fibroblasts, it is difficult to put this mechanism in the context of NF2 pathogenesis and other Merlin-deficient malignancies. It will be of great interest to see whether Merlin's interactions with α-catenin leads to the suppression of YAP- and β-catenin-mediated oncogenic gene expression in pathogenically-relevant tissues.

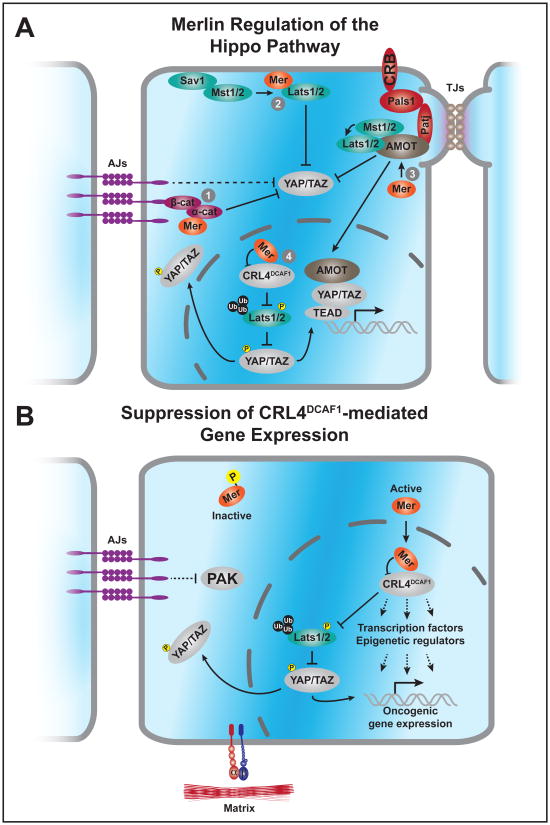

Figure 2.

(A) Merlin activates the Hippo pathway to suppress YAP/TAZ through regulation of core kinase components at the plasma membrane, through inhibition of the CRL4DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase in the nucleus, and by regulating cell junction-associated proteins that modulate Hippo signaling. (1) At adherens junctions, E-cadheren promotes Hippo signaling while α-catenin sequesters 14-3-3 protein-bound YAP. Merlin interacts with α-catenin at maturing adherens junctions in skin epithelium, plausibly influencing Hippo signaling at this subcellular compartment. (2) At the plasma membrane, Mn recruits the Lats kinases and coordinates their activation by Mst1, driving phosphorylation and inhibition of YAP/TAZ. (3) The Crumbs homolog (CRB) complex recruits Angiomotin (AMOT), which directly binds Hippo pathway components. AMOT serves as a scaffold for Mst1/2 and Lats1/2 activation and also directly binds and inhibits YAP. Conversely, the p180 isoform of AMOT promotes YAP function in the nucleus. Merlin interacts with AMOT at tight junctions to suppress Rac activity, however, it remains to be determined how Merlin influences Angiomotin's inhibition of YAP at tight junctions or YAP-activating functions in the nucleus. (4) Dephosphorylated Merlin translocates to the nucleus and inhibits CRL4DCAF1, preventing this E3 ligase from ubiquitinating and inhibiting Lats1/2. These core Hippo pathway components, activated by an upstream kinase, phosphorylate and inactivate YAP/TAZ.

(B) Merlin's regulation of CRL4DCAF1 impinges on multiple downstream epigenetic mechanisms and blocks oncogenic gene expression. In contact inhibited cells, active Merlin translocates to the nucleus where it binds to and inhibits the CRL4DCAF1 E3 Ubiquitin ligase. Active or dysregulated CRL4DCAF1 induces an oncogenic gene expression program by promoting downstream Hippo pathway targets via inhibition of the Lats1/2 kinases and through modulation of epigenetic modifiers and transcription factors.

Merlin interacts with the scaffold and signaling protein Angiomotin at mature tight junctions, regulating contact inhibition and potentially tumor suppression (Fig. 2A) [28]. Angiomotin exists in two isoforms - both of which interact with Merlin - and associate with tight junctions through interactions with Patj, Pals1, and Mupp1 [69,70]. At assembled tight junctions, Merlin binds to Angiomotin and displaces Rich - a GTPase Activating Protein for Rac - thus suppressing Rac-PAK signaling [28]. Therefore, Merlin's inhibition of Rac at tight junctions promotes contact inhibition and acts as a barrier to mitogenic signaling [7]. One major caveat to this finding is that Angiomotin interacts not only with Merlin's α-helical and carboxy-terminal domains, but also with phospho-deficient and phospho-mimetic Merlin mutants [28]. These results strongly imply that Merlin binds to Angiomotin regardless of its activation status, and therefore, independently of growth suppressive stimuli. Further work is needed to fully understand the role of Angiomotin in Merlin's function in normal cells and in Merlin-deficient tumorigenesis.

A fraction of Merlin has been found to localize to cholesterol-dependent membrane domains -which were interpreted as lipid rafts - as a result of phosphoinositide binding [71,72]. Active Merlin was shown to bind phosphoinositides in several studies, although there is contradicting evidence as to whether this occurs in Merlin's active or inactive forms [72,73], raising uncertainty over the relevance of this interaction to adhesion signaling. However, a Merlin mutant lacking residues necessary for phosphoinositide binding - K79, K80, K269, E270, K278, and K279 - was significantly defective in suppressing growth of Merlin-deficient cells [72]. This observation was supported by experiments confirming that the Merlin mutant retained normal folding. However, the ability of the phosphoinositide-binding mutant to interact with other proteins that were previously shown to mediate Merlin's function was not tested. Notably, mutation of Merlin E270 abolishes interaction with CRL4DCAF1, which could explain the growth-suppression defects of the phosphoinositide-binding mutant [29]. Merlin's phosphoinositide binding and potential localization to lipid rafts requires further scrutiny to determine its relevance both in normal biological function and in Merlin-deficient pathogenesis.

In addition to Merlin's localization at the cortex and contact-dependent membrane domains, Merlin functions in the cytoplasm to control cytoskeletal dynamics and vesicular transport. Merlin associates with actin and tubulin in the cytoplasm [32,74,75], although Merlin's association with the actin cytoskeleton is dispensable for tumorigenesis [32,76]. Merlin migrates along microtubules in a kinesin-1- and dynein-dependent manner [75], and Merlin was recently found to slow the turnover of microtubules, thus stabilizing them [77]. In addition, Merlin has been found to promote microtubule-mediated anterograde transport of vesicles [78], which could function in promoting the transport of anti-mitogenic biomolecules or regulating the availability of growth factors at the plasma membrane. Merlin's effects on the actin cytoskeleton do not appear to be pathogenically relevant, and it remains to be demonstrated whether regulation of microtubule dynamics is necessary in Merlin-mediated contact inhibition and tumor suppression in vivo. Therefore, current models imply that Merlin largely enforces contact inhibition and the organization of membrane domains by acting at the plasma membrane or cortex, while Merlin's strongest tumor suppressive functions are enforced in another cellular compartment.

Nuclear Localization and Inhibition of CRL4DCAF1

Dephosphorylated Merlin translocates to the nucleus where it binds to and inhibits the CRL4DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase (Fig 2B) [29], which was the first identification of a nuclear binding partner for Merlin. Observation that the dephosphorylated form of Merlin preferentially translocates to the nucleus while the phosphorylated form is largely excluded is consistent with the long-standing observation that Merlin suppresses tumorigenesis in its dephosphorylated form [27,29,32,49]. Moreover, several reports have characterized Merlin's localization in the nucleus, and Merlin migrates towards the nucleus by microtubule-based transport in Drosophila [57,75,79,80]. Although Merlin lacks a canonical nuclear localization sequence, it contains a motif on its carboxy-terminus that promotes nuclear export by the CRM1-exportin pathway [80], and truncations that remove these residues show increased nuclear localization [29,32]. Interestingly, the isolated FERM domain of Merlin is necessary and sufficient for nuclear localization, once again highlighting the importance of Merlin's FERM domain in its normal function (Table 1) [29]. Moreover, the dephosphorylated form of Merlin preferentially localizes to the nucleus in confluent and growth factor-deprived cells, when Merlin's anti-mitogenic effects would be most active [29]. As the phosphorylated, more closed form of Merlin is excluded from the nucleus, interdomain binding imposed by S518 phosphorylation may occlude the FERM domain residues necessary for nuclear translocation [27,29]. Since a large proportion of Merlin shuttles to the nucleus in contact-inhibited cells, Merlin's nuclear function - particularly inhibition of the oncogenic CRL4DCAF1 ubiquitin ligase - may be vital for growth suppression [29]. Indeed, multiple lines of evidence suggest that Merlin suppresses tumorigenesis largely through inhibition of CRL4DCAF1. Genetic epistasis experiments in several cell lines - including pathogenically relevant human schwannoma and mesothelioma cells - reveal that Merlin mediates its tumor suppressive and anti-mitogenic effects through inhibition of CRL4DCAF1. Notably, multiple patient-derived Merlin missense mutants are unable to interact with DCAF1 as a result of nuclear localization defects, disruption of Merlin-DCAF1 binding, or a combination of these aberrations (Table 1) [29]. Understanding more about CRL4DCAF1 biology and its interaction with Merlin and other binding partners is an important step in conceptualizing how Merlin's inhibition of this E3 ligase is an important stepping stone in the control of multiple pro-oncogenic signaling pathways.

Table 1.

Patient-derived NF2 mutations abrogate Merlin's regulation of CRL4DCAF1. The indicated patient-derived missense and truncation mutants are defective in nuclear translocation, direct binding to CRL4DCAF1 suppression of CRL4DCAF1-mediated ubiquitination, or a combination of these mechanisms. As a result, the NF2-derived missense mutants are unable to interact with CRL4DCAF1 In vivo permitting the dysregulated ligase to promote tumorigenesis. NT, not tested. Data were obtained from Li et al, 2010 [29].

|

DCAF1 (DDB1 and Cul4-Associated Factor 1) was originally identified as VprBp (Vpr-binding protein) – a cytoplasmic protein that binds to the HIV-1 viral accessory protein Vpr [81,82], before it was found to function as the substrate recognition subunit of the CRL4DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase [83]. Viral Vpr and the related Vpx proteins promote HIV and SIV infection by functioning as adaptors that bind to DCAF1 and usurp its recruitment of substrates to degrade proteins that normally suppress viral infectivity [84,85]. In fact, viral subversion of E3 ubiquitin ligases occurs in a number of human diseases [83,86-89]. SAMHD1 is a viral restriction factor which functions in myeloid-lineage cells and resting CD4+ T-cells by reducing the concentration of cellular dNTPs and thus inhibiting the viral reverse transcriptase. In HIV-2 and SIV, Vpx binds to DCAF1 and acts as an adaptor to co-opt the ubiquitin-conjugating machinery to target and degrade SAMHD1 [90-95]. A recent landmark study found that Vpx binds the WD40 domain of DCAF1 to produce a new surface that recruits SAMHD1, providing the first structural elucidation of lentiviral hijacking of the cell's ubiquitin-proteasome system [96]. These studies provide a starting point to understand how CRL4DCAF1 binds its targets, and furthermore, how Merlin may serve as an inhibitory pseudo-substrate (Fig. 3A).

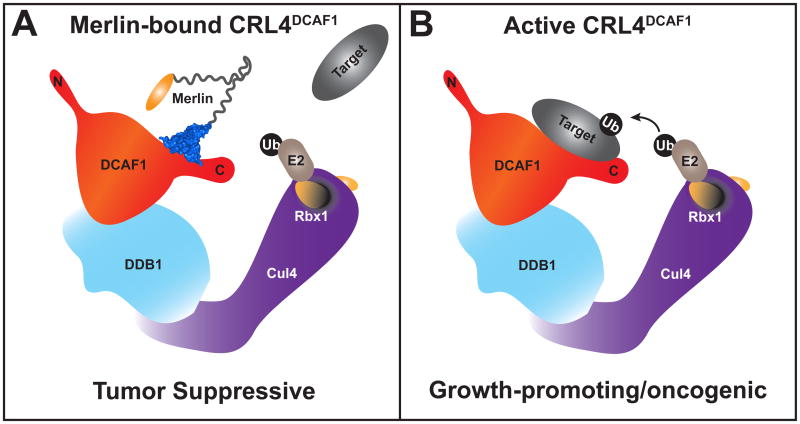

Figure 3.

(A) Active Merlin translocates to the nucleus and binds to the carboxy-terminus of DCAF1, acting as a pseudo-substrate to block CRL4DCAF1 from recruiting and ubiquitinating target proteins. Merlin's inhibition of CRL4DCAF1 suppresses oncogenic gene expression. (B) CRL4DCAF1 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase consisting of the substrate-recruiting DCAF1 protein which is linked to the amino-terminal domain of a cullin (Cul4A/B) backbone through DDB1, which is itself a large multi-domain protein. Bound to the cullin carboxy-terminal domain, Rbx1 uses its RING domain to recruit a ubiquitin-charged E2, which directs conjugation of ubiquitin to a DCAF1-bound target protein.

Structural analysis of the DCAF1-Vpx-SAMHD1 complex revealed that Vpx creates a new binding surface by enclosing a portion of the DCAF1 WD40 domain. The WD40 domain of DCAF1, near the carboxy-terminus, is a seven-bladed β-propeller that forms an overall fan shape [96]. Residues within the WD40 domain are necessary for interacting with DDB1 and therefore docking to the CRL4 complex [83]. As Vpx-associated DCAF1 is able to recruit SAMHD1 and mediate its ubiquitination [96], it is plausible that DCAF1 uses portions of its WD40 domain to bind native targets. A recent study found that DCAF1 can recruit mono-methylated proteins using the hydrophobic pocket within its chromo domain, which resides in the amino-terminal half of the protein [97]. In addition to the role of CRL4DCAF1 in ubiquitination, DCAF1 has a putative kinase domain near the amino-terminus which imparts intrinsic kinase activity towards histone H2A to downregulate anti-mitogenic genes [98]. Combined, these studies reveal that DCAF1 can interact with multiple target proteins using several distinct regions spanning its primary sequence. However, without further structural characterization of full-length DCAF1, it cannot be ruled out that these domains are juxtaposed, and that one or more protein-interacting regions act in a single multifunctional recruitment domain.

DCAF1 was established as the substrate recognition component of the CRL4DCAF1 E3 ligase (Fig. 3B) nearly ten years ago [83], and several CRL4DCAF1 targets have been discovered. Vpr-and Vpx-mediated targeting of SAMHD1 and the uracil DNA glycosylase UNG2 direct these proteins to proteasomal degradation [91,99]. Moreover, it was found that CRL4DCAF1 is recruited by Vpr to activate the SLX4 complex, a structure-specific endonuclease whose ectopic activation results in G2/M arrest and evasion of innate immunity in HIV-infected cells [100]. Native DCAF1 -binding proteins include Merlin, the nuclear orphan receptor Rorα, histones H2A and H3, HDAC, the polarity protein Lgl, the lymphoid cell-specific V(D)J recombination protein RAG1, and the replication factor Mcm10 [29,97,101-104]. Several of these proteins -particularly the histones and HDAC – can broadly affect epigenetics, suggesting that Merlin's inhibition of CRL4DCAF1 can greatly alter gene expression. It was recently observed that CRL4DCAF1 interacts with and promotes activation of TET proteins, a family of enzymes that convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) [105]. These conversions cause epigenetic modifications that regulates DNA demethylation and therefore gene transcription, which were shown to have dramatic effects during embryonic development and tumorigenesis. Notably, loss of TET2 is a common occurrence in myeloid leukemia and 5hmC reduction is a distinguishing feature of melanoma and is observed in a range of other solid tumors [106]. However, the mechanism by which CRL4DCAF1 regulates TET proteins – whether by ubiquitination or another modification – is currently unknown. Indeed, the mechanism by which CRL4DCAF1 modulates several bona fide interactors remains elusive, and it is unclear whether ubiquitination of these targets is necessary or sufficient for their regulation. Regardless, these findings suggest that CRLDCAF1 can multifariously modulate epigenetics (Fig. 2B), and its dysregulation following Merlin deficiency shifts cells towards an oncogenic gene expression program. Indeed, Merlin expression and DCAF1 knockdown in Merlin-deficient cells reveal that Merlin suppresses tumorigenesis largely through DCAF1 inhibition, providing further support that Merlin regulates oncogenic gene expression through its inhibition of the CRL4DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase [29].

Merlin's FERM domain binds the carboxy-terminal acidic tail of DCAF1, which is outside of the WD40 domain [29]. Since the DCAF1 acidic tail is adjacent to its WD40 domain in its primary sequence, it is possible that Merlin's binding to the tail brings it in close proximity to the binding surface of the WD40 propeller (Fig. 3A). However, many possibilities exist to explain how Merlin can reduce CRL4DCAF1 activity [29], which is further complicated by the multiple protein-interacting domains within DCAF1. A groundwork explanation is that Merlin occludes one or more of the DCAF1 targeting domains without significant structural perturbation. In addition to -or instead of - direct competition of target recruitment, Merlin's binding may cause dramatic structural alterations, thus attenuating DCAF1 targeting abilities. Further biochemical studies and structural analyses will be paramount in gaining mechanistic insight into Merlin's inhibition of CRL4DCAF1.

Convergence on YAP and TAZ

The size of multicellular organisms and their composite tissues is tightly regulated by restricting cell size and proliferation [107,108]. The Hippo pathway has emerged as a potent regulator of organ size throughout the animal kingdom. Notably, genetic experiments in Drosophila and mice revealed that the Hippo pathway controls cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis, and disruption of the pathway at multiple levels leads to tissue overgrowth and tumorigenesis [109,110]. This is particularly evident in mouse genetic models, where dysregulation of Hippo pathway proteins in the liver elicits dramatic hepatomegaly and development of a range of tumors [24,111-114]. The Hippo pathway is canonically driven by a core kinase cascade consisting of the Ste20-like kinases Mst1 and Mst2 (Mst1/2), which in conjunction with Sav1, phosphorylate and activate the NDR family kinases Lats1 and Lats2 (Lats1/2) along with cofactors Mob1A and Mob1B. Active Lats kinases phosphorylate and inactivate the YAP and TAZ transcriptional coactivators (Fig. 2A). In the absence of Hippo signaling, active YAP and TAZ translocate to the nucleus to promote transcription of genes that drive proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and stemness [26,115]. The atypical cadherin Fat, along with the apical polarity protein Crumbs, function in Drosophila to activate the Hippo pathway. These proteins activate the FERM domain protein Expanded, which complexes with Merlin and Kibra to activate the core kinase cascade [116-119]. Although the core kinase cascade is evolutionary conserved between Mammals and Drosophila, the upstream signaling promoting activation of the Hippo pathway has diverged.

It has recently become evident that some of the key proteins regulating the core Hippo cascade in Drosophila evolved after the divergence of arthropods. It is unclear whether Drosophila Expanded (Ex) and Fat have orthologs in vertebrates, and the mammalian proteins which bare closest resemblance appear to function primarily through Hippo-independent mechanisms [120-123]. The adherens junction protein Echinoid and the unconventional myosin Dachs - a downstream target of Fat - regulate the Drosophila Hippo pathway but are absent in vertebrates. Angiomotin was retained during the evolution of chordates as a regulator of Hippo signaling but was replaced with Ex at the base of the arthropod lineage [123]. The evolution of a novel domain in Ex to bind Yki - the Drosophila ortholog of YAP - reestablished Crumbs-mediated regulation of Hippo signaling which was uncoupled when the PDZ-binding motif of Yki was lost during arthropod evolution. In addition to these evolutionary shifts in regulation of Hippo signaling, Merlin's input into the pathway appears to be more complicated in mammals.

It is becomingly increasingly clear in mammals that multiple signals converge to affect the Hippo core kinase cascade in addition to canonical Hippo signaling [115]. Upstream of the core cassette, Merlin can interact with Kibra to activate the Hippo kinase cascade, although the biochemical mechanism is unclear [24,117]. Merlin is recruited to tight junctions by Angiomotin, which serves as a scaffold for PDZ- and WW-domain- containing proteins including Hippo pathway components (Fig. 2A) [124-127]. Interestingly, tight junction-associated Angiomotin directly binds phosphorylated YAP and TAZ and retains them at the cortex [124,127] and also serves as a scaffold for activation of the Hippo core kinases Mst2 and Lats2, promoting canonical YAP/TAZ inhibition [125]. Since Merlin binds to Angiomotin and displaces other complexed proteins, it is plausible that Merlin's binding could modulate Angiomotin recruitment of Hippo components. It remains to be tested whether Merlin promotes or inhibits Angiomotin's direct effects on Hippo signaling. Recently it was found that the p130 isoform of Angiomotin promotes YAP function by disrupting its association with Lats1 in the cytoplasm, and furthermore, by binding to YAP in the nucleus to drive expression of a subset of YAP target genes to drive tumorigenesis (Fig. 2A) [128]. It will be of great interest to determine whether Angiomotin is shuttled to the nucleus to promote YAP function in sparse cells or cells that have had their tight junctions disrupted. Combined, these results suggest Angiomotin has tumor suppressive and growth-promoting functions, which may depend on the tissue, cellular, or biochemical environment. Identification of the contexts in which Angiomotin functions to inhibit or promote Hippo signaling - including the biochemical function of Merlin in these processes – will provide important mechanistic insight into both Merlin function and Hippo signaling.

Drosophila genetics experiments provided strong evidence that Merlin functions with Ex to activate Hippo signaling [25]. However, two recent landmark studies revealed separate, nonlinear mechanisms by which Merlin promotes Hippo signaling. DJ Pan's group found that Merlin could directly bind to Wts/Lats in both Drosophila and mammals, recruiting these proteins to the plasma membrane to be phosphorylated by active Mst1/2 (Fig. 2A) [129]. This study further used genetic experiments in mammalian cells to show that Merlin promotes downstream Hippo signaling independently of Mst1/2, revealing Merlin's direct biochemical role in regulating the Hippo pathway. More recently, however, our group found that dysregulated CRL4DCAF1 promotes YAP function and TEAD-dependent transcription by ubiquitinating and inhibiting Lats1/2 in the nucleus (Fig. 2A) [130]. Genetic experiments and analysis of Merlin mutations revealed that CRL4DCAF1-mediated inhibition of Lats1/2 sustains the tumorigenicity of Merlin-deficient cells. Compellingly, analysis of clinical samples strongly suggested that this YAP- and TAZ-promoting circuit of the Hippo pathway functions in Merlin-deficient malignancies. Furthermore, our experiments revealed that tumor-derived Merlin mutants are invariably defective in binding to CRL4DCAF1 yet retain Lats1 binding providing genetic evidence that Merlin's interaction with Lats1 at the plasma membrane is not sufficient to suppress tumorigenesis. Merlin's recruitment of Lats1 at the plasma membrane is an important and evolutionary conserved non-canonical Hippo pathway mechanism. However, it appears that Merlin's suppression of the CRL4DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase is a paramount tumor suppressive clamp embedded in the human Hippo pathway. In vivo insight into the contribution of both of these mechanisms in mammals will be an essential step in validating their significance in the context of normal function and tumorigenesis. These findings further emphasize the lack of conservation between the linear model for Hippo activation in Drosophila and the multifarious regulation of YAP and TAZ in mammals. Combined, insights over the past five years have shown that Merlin regulates the Hippo pathway at multiple levels, yet these signals seem to invariably converge to regulate YAP and TAZ activation [115]. As a next step, it will be important to determine the spatio-temporal hierarchy of Merlin's effects on Hippo signaling and the importance of these pathways in pathogenically relevant tissues, which may unmask the most significant drugable targets for Merlin-deficient malignancies.

Conclusions

The biochemical mechanisms underlying Merlin-mediated growth suppression are unraveling at an accelerating rate, with several critical observations occuring within the past five years. It is becoming increasingly clear that Merlin suppresses cell proliferation through two modes that are defined by functions at the cortex or in the nucleus. By linking Par3 to α-catenin at adherens junctions, Merlin promotes cell adhesions and thereby tissue organization in skin epithelium [59]. At tight junctions, Merlin's binding to Angiomotin releases Rich, which inactivates Rac and thereby attenuates mitogenic signaling [7,28]. As Angiomotin directly suppresses Hippo signaling in the cytoplasm [124,125,127] and promotes YAP activity in the nucleus [128], further insight is needed to understand the contextual relevance of these observations as well as how Merlin may be involved. Moreover, as α-catenin inhibits YAP and Wnt-β-catenin signaling, Merlin's potential regulation of these pathways through interactions with α-catenin warrants investigation. In contrast to Merlin's cortex-specific roles that largely influence cell junctions and Rac signaling, intercellular and cortical cues lead to accumulation of dephosphorylated Merlin, which translocates to the nucleus and attenuates oncogenic gene expression via inhibition of CRL4DCAF1 [29] As CRL4DCAF1 regulates several proteins that broadly control transcription and epigenetics [98,104,105], Merlin is poised to dramatically alter the expression of genes in response to adhesion signaling. Furthermore, Merlin's inhibition of CRL4DCAF1 prevents this E3 ligase from ubiquitinating and inhibitiing the Lats kinases, maintaining a clamp to restrict Hippo signaling to YAP [130]. Along with the findings that Merlin recruits Lats1 at the plasma membrane to promote Hippo signaling, these recently discovered mechansims link Merlin to a pathway that has potent affects on cell proliferation, stemness, and contact inhibition [1,115,129,130].

Recently, it was found that genetic ablation of Merlin promotes drug resistance in melanoma, suggesting that loss of Merlin can drive tumor evolution following initial cancer-causing oncogenic insults [131]. This finding reiterates Merlin's broad tumor suppressive role and highlights the need to establish Merlin's biochemical functions in normal tissue and to delineate the vital pathways dysregulated in Merlin-deficient tumorigenesis. The signaling pathways known to be regulated by Merlin lay as a cornerstone for understanding Merlin's functions in adhesion signaling and tumor suppression. Research to define the importance and hierarchy of these pathways, particularly in the pursuit of drugable targets in Merlin-deficient tumors, can be expected in the near future. While in vivo models will be paramount in identifying and alleviating pathogenic aberrations resulting from Merlin loss, biochemical investigation - including full-length crystallographic analyses of the inactive and active forms of Merlin - will simultaneously shed light on Merlin's normal function and guide the advent of therapies targeting Merlin-deficient malignancies.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Wei Li and Kelly Gillen for their insights and comments on the manuscript, my fellow lab members for their support, and my mentor for his guidance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McClatchey AI, Yap AS. Contact inhibition (of proliferation) redux. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:685–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouleau GA, et al. Alteration in a new gene encoding a putative membrane-organizing protein causes neuro-fibromatosis type 2. Nature. 1993;363:515–21. doi: 10.1038/363515a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trofatter J, et al. A novel moesin-, ezrin-, radixin-like gene is a candidate for the neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor. Cell. 1993;75:826. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90501-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lallemand D, Curto M, Saotome I, Giovannini M, McClatchey AI. NF2 deficiency promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis by destabilizing adherens junctions. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1090–100. doi: 10.1101/gad.1054603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison H, et al. The NF2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, mediates contact inhibition of growth through interactions with CD44. Genes Dev. 2001;15:968–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.189601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada T, Lopez-Lago M, Giancotti FG. Merlin/NF-2 mediates contact inhibition of growth by suppressing recruitment of Rac to the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:361–71. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng JQ, Lee WC, Klein MA, Cheng GZ, Jhanwar SC, Testa JR. Frequent mutations of NF2 and allelic loss from chromosome band 22q12 in malignant mesothelioma: evidence for a two-hit mechanism of NF2 inactivation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;24:238–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bott M, et al. The nuclear deubiquitinase BAP1 is commonly inactivated by somatic mutations and 3p21.1 losses in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:668–72. doi: 10.1038/ng.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bianchi AB, et al. Mutations in transcript isoforms of the neurofibromatosis 2 gene in multiple human tumour types. Nat Genet. 1994;6:185–92. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalgliesh GL, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 2010;463:360–3. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau YK, Murray LB, Houshmandi SS, Xu Y, Gutmann DH, Yu Q. Merlin is a potent inhibitor of glioma growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5733–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rustgi AK, Xu L, Pinney D, Sterner C, Beauchamp R, Schmidt S, Gusella JF, Ramesh V. Neurofibromatosis 2 gene in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1995;84:24–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(95)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McClatchey AI, Fehon RG. Merlin and the ERM proteins--regulators of receptor distribution and signaling at the cell cortex. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaempchen K, Mielke K, Utermark T, Langmesser S, Hanemann CO. Upregulation of the Rac1/JNK signaling pathway in primary human schwannoma cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1211–21. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kissil JL, Wilker EW, Johnson KC, Eckman MS, Yaffe MB, Jacks T. Merlin, the product of the Nf2 tumor suppressor gene, is an inhibitor of the p21-activated kinase, Pak1. Mol Cell. 2003;12:841–9. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00382-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw RJ, et al. The Nf2 tumor suppressor, merlin, functions in Rac-dependent signaling. Dev Cell. 2001;1:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James MF, Han S, Polizzano C, Plotkin SR, Manning BD, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Gusella JF, Ramesh V. NF2/merlin is a novel negative regulator of mTOR complex 1, and activation of mTORC1 is associated with meningioma and schwannoma growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4250–61. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01581-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez-Lago MA, Okada T, Murillo MM, Socci N, Giancotti FG. Loss of the tumor suppressor gene NF2, encoding merlin, constitutively activates integrin-dependent mTORC1 signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4235–49. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01578-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rong R, Tang X, Gutmann DH, Ye K. Neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) tumor suppressor merlin inhibits phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase through binding to PIKE-L. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18200–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405971102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poulikakos PI, Xiao GH, Gallagher R, Jablonski S, Jhanwar SC, Testa JR. Re-expression of the tumor suppressor NF2/merlin inhibits invasiveness in mesothelioma cells and negatively regulates FAK. Oncogene. 2006;25:5960–5968. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin H, Sperka T, Herrlich P, Morrison H. Tumorigenic transformation by CPI-17 through inhibition of a merlin phosphatase. Nature. 2006;442:576–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ammoun S, Flaiz C, Ristic N, Schuldt J, Hanemann CO. Dissecting and targeting the growth factor-dependent and growth factor-independent extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in human schwannoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5236–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang N, et al. The Merlin/NF2 tumor suppressor functions through the YAP oncoprotein to regulate tissue homeostasis in mammals. Dev Cell. 2010;19:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamaratoglu F, Willecke M, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Hyun E, Tao C, Jafar-Nejad H, Halder G. The tumour-suppressor genes NF2/Merlin and Expanded act through Hippo signalling to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:27–36. doi: 10.1038/ncb1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao B, et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2747–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sher I, Hanemann CO, Karplus PA, Bretscher A. The tumor suppressor merlin controls growth in its open state, and phosphorylation converts it to a less-active more-closed state. Dev Cell. 2012;22:703–5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yi C, et al. A tight junction-associated Merlin-angiomotin complex mediates Merlin's regulation of mitogenic signaling and tumor suppressive functions. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:527–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li W, et al. Merlin/NF2 suppresses tumorigenesis by inhibiting the E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4(DCAF1) in the nucleus. Cell. 2010;140:477–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherman L, Xu H, Geist R, Saporito-Irwin S, Howells N, Ponta H, Herrlich P, Gutmann D. Interdomain binding mediates tumor growth suppression by the NF2 gene product. Oncogene. 1997;15:2505–2509. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez-Agosti C, Wiederhold T, Herndon ME, Gusella J, Ramesh V. Interdomain interaction of merlin isoforms and its influence on intermolecular binding to NHE- RF. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34438–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lallemand D, Saint-Amaux AL, Giovannini M. Tumor-suppression functions of merlin are independent of its role as an organizer of the actin cytoskeleton in Schwann cells. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:4141–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.045914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bretscher A, Edwards K, Fehon RG. ERM proteins and merlin: integrators at the cell cortex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:586–99. doi: 10.1038/nrm882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimizu T, Seto A, Maita N, Hamada K, Tsukita S, Hakoshima T. Structural basis for neurofibromatosis type 2. Crystal structure of the merlin FERM domain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10332–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109979200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson KC, Kissil JL, Fry JL, Jacks T. Cellular transformation by a FERM domain mutant of the Nf2 tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2002;21:5990–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LaJeunesse DR, McCartney BM, Fehon RG. Structural analysis of Drosophila merlin reveals functional domains important for growth control and subcellular localization. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1589–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gary R, Bretscher A. Ezrin self-association involves binding of an N-terminal domain to a normally masked C-terminal domain that includes the F-actin binding site. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1061–75. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.8.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Q, Nance MR, Kulikauskas R, Nyberg K, Fehon R, Karplus PA, Bretscher A, Tesmer JJ. Self-masking in an intact ERM-merlin protein: an active role for the central alpha-helical domain. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:1446–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearson MA, Reczek D, Bretscher A, Karplus PA. Structure of the ERM protein moesin reveals the FERM domain fold masked by an extended actin binding tail domain. Cell. 2000;101:259–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80836-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heiska L, Alfthan K, Grönholm M, Vilja P, Vaheri A, Carpén O. Association of ezrin with intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and -2 (ICAM-1 and ICAM-2). Regulation by phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21893–900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsukita S, Oishi K, Sato N, Sagara J, Kawai A. ERM family members as molecular linkers between the cell surface glycoprotein CD44 and actin-based cytoskeletons. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:391–401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen R, Reczek D, Bretscher A. Hierarchy of merlin and ezrin N- and C-terminal domain interactions in homo- and heterotypic associations and their relationship to binding of scaffolding proteins EBP50 and E3KARP. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7621–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006708200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gutmann DH, Haipek CA, Hoang Lu K. Neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor protein, merlin, forms two functionally important intramolecular associations. J Neurosci Res. 1999;58:706–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meng JJ, et al. Interaction between two isoforms of the NF2 tumor suppressor protein, merlin, and between merlin and ezrin, suggests modulation of ERM proteins by merlin. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:491–502. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001115)62:4<491::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rong R, Surace EI, Haipek CA, Gutmann DH, Ye K. Serine 518 phosphorylation modulates merlin intramolecular association and binding to critical effectors important for NF2 growth suppression. Oncogene. 2004;23:8447–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Surace EI, Haipek CA, Gutmann DH. Effect of merlin phosphorylation on neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) gene function. Oncogene. 2004;23:580–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hennigan RF, Foster LA, Chaiken MF, Mani T, Gomes MM, Herr AB, Ip W. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis of merlin conformational changes. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:54–67. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00248-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahronowitz I, Xin W, Kiely R, Sims K, MacCollin M, Nunes FP. Mutational spectrum of the NF2 gene: a meta-analysis of 12 years of research and diagnostic laboratory findings. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:1–12. doi: 10.1002/humu.20393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kissil JL, Johnson KC, Eckman MS, Jacks T. Merlin phosphorylation by p21- activated kinase 2 and effects of phosphorylation on merlin localization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10394–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serrano I, McDonald PC, Lock F, Muller WJ, Dedhar S. Inactivation of the Hippo tumour suppressor pathway by integrin-linked kinase. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2976. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaw R, et al. The Nf2 tumor suppressor, merlin, functions in Rac-dependent signaling. Developmental cell. 2001;1:63–72. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaw RJ, McClatchey AI, Jacks T. Regulation of the neurofibromatosis type 2 tumor suppressor protein, merlin, by adhesion and growth arrest stimuli. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7757–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laulajainen M, Muranen T, Carpen O, Gronholm M. Protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of the NF2 tumor suppressor protein merlin at serine 10 affects the actin cytoskeleton. Oncogene. 2008;27:3233–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alfthan K, Heiska L, Gronholm M, Renkema GH, Carpen O. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylates merlin at serine 518 independently of p21-activated kinase and promotes merlin-ezrin heterodimerization. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18559–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim HA, DeClue JE, Ratner N. cAMP-dependent protein kinase A is required for Schwann cell growth: interactions between the cAMP and neuregulin/tyrosine kinase pathways. J Neurosci Res. 1997;49:236–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang X, et al. Akt phosphorylation regulates the tumour-suppressor merlin through ubiquitination and degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1199–207. doi: 10.1038/ncb1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qi Q, Liu X, Brat DJ, Ye K. Merlin sumoylation is required for its tumor suppressor activity. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McClatchey AI, Giovannini M. Membrane organization and tumorigenesis--the NF2 tumor suppressor, Merlin. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2265–77. doi: 10.1101/gad.1335605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gladden AB, Hebert AM, Schneeberger EE, McClatchey AI. The NF2 tumor suppressor, Merlin, regulates epidermal development through the establishment of a junctional polarity complex. Dev Cell. 2010;19:727–39. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sainio M, et al. Neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor protein colocalizes with ezrin and CD44 and associates with actin-containing cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 18):2249–60. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.18.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCartney BM, Fehon RG. Distinct cellular and subcellular patterns of expression imply distinct functions for the Drosophila homologues of moesin and the neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor, merlin. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:843–52. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.4.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shaw RJ, McClatchey AI, Jacks T. Localization and functional domains of the neurofibromatosis type II tumor suppressor, merlin. Cell Growth Differ. 1998;9:287–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gonzalez-Agosti C, Xu L, Pinney D, Beauchamp R, Hobbs W, Gusella J, Ramesh V. The merlin tumor suppressor localizes preferentially in membrane ruffles. Oncogene. 1996;13:1239–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scherer S, Gutmann D. Expression of the neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, in Schwann cells. Journal of neuroscience research. 1996;46:595–605. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19961201)46:5<595::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murthy A, Gonzalez-Agosti C, Cordero E, Pinney D, Candia C, Solomon F, Gusella J, Ramesh V. NHE-RF, a regulatory cofactor for Na(+)-H+ exchange, is a common interactor for merlin and ERM (MERM) proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1273–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schlegelmilch K, et al. Yap1 acts downstream of alpha-catenin to control epidermal proliferation. Cell. 2011;144:782–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Silvis MR, et al. alpha-catenin is a tumor suppressor that controls cell accumulation by regulating the localization and activity of the transcriptional coactivator Yap1. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra33. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Choi SH, Estarás C, Moresco JJ, Yates JR, Jones KA. α-Catenin interacts with APC to regulate β-catenin proteolysis and transcriptional repression of Wnt target genes. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2473–88. doi: 10.1101/gad.229062.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wells CD, et al. A Rich1/Amot complex regulates the Cdc42 GTPase and apical-polarity proteins in epithelial cells. Cell. 2006;125:535–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ernkvist M, et al. The Amot/Patj/Syx signaling complex spatially controls RhoA GTPase activity in migrating endothelial cells. Blood. 2009;113:244–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-153874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stickney JT, Bacon WC, Rojas M, Ratner N, Ip W. Activation of the tumor suppressor merlin modulates its interaction with lipid rafts. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2717–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mani T, Hennigan RF, Foster LA, Conrady DG, Herr AB, Ip W. FERM domain phosphoinositide binding targets merlin to the membrane and is essential for its growth- suppressive function. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1983–96. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00609-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Okada M, Wang Y, Jang SW, Tang X, Neri LM, Ye K. Akt phosphorylation of merlin enhances its binding to phosphatidylinositols and inhibits the tumor-suppressive activities of merlin. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4043–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brault E, Gautreau A, Lamarine M, Callebaut I, Thomas G, Goutebroze L. Normal membrane localization and actin association of the NF2 tumor suppressor protein are dependent on folding of its N-terminal domain. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1901–12. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.10.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bensenor LB, Barlan K, Rice SE, Fehon RG, Gelfand VI. Microtubule-mediated transport of the tumor-suppressor protein Merlin and its mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7311–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907389107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xu HM, Gutmann DH. Merlin differentially associates with the microtubule and actin cytoskeleton. J Neurosci Res. 1998;51:403–15. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980201)51:3<403::AID-JNR13>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smole Z, Thoma CR, Applegate KT, Duda M, Gutbrodt KL, Danuser G, Krek W. Tumor Suppressor NF2/Merlin Is a Microtubule Stabilizer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:353–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hennigan RF, Moon CA, Parysek LM, Monk KR, Morfini G, Berth S, Brady S, Ratner N. The NF2 tumor suppressor regulates microtubule-based vesicle trafficking via a novel Rac, MLK and p38(SAPK) pathway. Oncogene. 2013;32:1135–43. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Muranen T, Gronholm M, Renkema GH, Carpen O. Cell cycle-dependent nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the neurofibromatosis 2 tumour suppressor merlin. Oncogene. 2005;24:1150–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kressel M, Schmucker B. Nucleocytoplasmic transfer of the NF2 tumor suppressor protein merlin is regulated by exon 2 and a CRM1-dependent nuclear export signal in exon 15. Human Molecular Genetics. 2002;11:2269–2278. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.19.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang S, Feng Y, Narayan O, Zhao LJ. Cytoplasmic retention of HIV-1 regulatory protein Vpr by protein-protein interaction with a novel human cytoplasmic protein VprBP. Gene. 2001;263:131–40. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00583-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhao LJ, Mukherjee S, Narayan O. Biochemical mechanism of HIV-I Vpr function. Specific interaction with a cellular protein. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15577–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Angers S, Li T, Yi X, MacCoss MJ, Moon RT, Zheng N. Molecular architecture and assembly of the DDB1-CUL4A ubiquitin ligase machinery. Nature. 2006;443:590–3. doi: 10.1038/nature05175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hrecka K, Gierszewska M, Srivastava S, Kozaczkiewicz L, Swanson S, Florens L, Washburn M, Skowronski J. Lentiviral Vpr usurps Cul4-DDB1[VprBP] E3 ubiquitin ligase to modulate cell cycle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:11778–11783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702102104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Le Rouzic E, Belaidouni N, Estrabaud E, Morel M, Rain JC, Transy C, Margottin-Goguet F. HIV1 Vpr arrests the cell cycle by recruiting DCAF1/VprBP, a receptor of the Cul4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:182–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.2.3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li T, Robert EI, van Breugel PC, Strubin M, Zheng N. A promiscuous alpha-helical motif anchors viral hijackers and substrate receptors to the CUL4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase machinery. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:105–11. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Andrejeva J, Poole E, Young DF, Goodbourn S, Randall RE. The p127 subunit (DDB1) of the UV-DNA damage repair binding protein is essential for the targeted degradation of STAT1 by the V protein of the paramyxovirus simian virus 5. J Virol. 2002;76:11379–86. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11379-11386.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li T, Chen X, Garbutt KC, Zhou P, Zheng N. Structure of DDB1 in complex with a paramyxovirus V protein: viral hijack of a propeller cluster in ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 2006;124:105–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Laguette N, et al. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature. 2011;474:654–7. doi: 10.1038/nature10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hrecka K, et al. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature. 2011;474:658–61. doi: 10.1038/nature10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lim ES, Fregoso OI, McCoy CO, Matsen FA, Malik HS, Emerman M. The ability of primate lentiviruses to degrade the monocyte restriction factor SAMHD1 preceded the birth of the viral accessory protein Vpx. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ahn J, Hao C, Yan J, DeLucia M, Mehrens J, Wang C, Gronenborn A, Skowronski J. HIV/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) accessory virulence factor Vpx loads the host cell restriction factor SAMHD1 onto the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex CRL4DCAF1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:12550–12558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.340711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Descours B, et al. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 reverse transcription in quiescent CD4(+) T-cells. Retrovirology. 2012;9:87. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Baldauf HM, et al. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4(+) T cells. Nat Med. 2012;18:1682–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schwefel D, Groom HC, Boucherit VC, Christodoulou E, Walker PA, Stoye JP, Bishop KN, Taylor IA. Structural basis of lentiviral subversion of a cellular protein degradation pathway. Nature. 2014;505:234–8. doi: 10.1038/nature12815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee J, et al. EZH2 generates a methyl degron that is recognized by the DCAF1/DDB1/CUL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Molecular cell. 2012;48:572–586. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kim K, et al. VprBP has intrinsic kinase activity targeting histone H2A and represses gene transcription. Mol Cell. 2013;52:459–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ahn J, Vu T, Novince Z, Guerrero-Santoro J, Rapic-Otrin V, Gronenborn AM. HIV-1 Vpr loads uracil DNA glycosylase-2 onto DCAF1, a substrate recognition subunit of a cullin 4A-ring E3 ubiquitin ligase for proteasome-dependent degradation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37333–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.133181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Laguette N, et al. Premature Activation of the SLX4 Complex by Vpr Promotes G2/M Arrest and Escape from Innate Immune Sensing. Cell. 2014;156:134–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tamori Y, et al. Involvement of Lgl and Mahjong/VprBP in cell competition. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kassmeier MD, et al. VprBP binds full-length RAG1 and is required for B-cell development and V(D)J recombination fidelity. EMBO J. 2012;31:945–58. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kaur M, Khan M, Kar A, Sharma A, Saxena S. CRL4-DDB1-VPRBP ubiquitin ligase mediates the stress triggered proteolysis of Mcm10. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:7332–7346. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kim K, Heo K, Choi J, Jackson S, Kim H, Xiong Y, An W. Vpr-binding protein antagonizes p53-mediated transcription via direct interaction with H3 tail. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:783–96. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06037-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yu C, et al. CRL4 complex regulates mammalian oocyte survival and reprogramming by activation of TET proteins. Science. 2013;342:1518–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1244587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tan L, Shi YG. Tet family proteins and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in development and disease. Development. 2012;139:1895–902. doi: 10.1242/dev.070771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Conlon I, Raff M. Size control in animal development. Cell. 1999;96:235–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lloyd AC. The regulation of cell size. Cell. 2013;154:1194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pan D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2010;19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhao B, Tumaneng K, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue regeneration and stem cell self-renewal. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:877–83. doi: 10.1038/ncb2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhou D, et al. Mst1 and Mst2 maintain hepatocyte quiescence and suppress hepatocellular carcinoma development through inactivation of the Yap1 oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:425–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lee KP, et al. The Hippo-Salvador pathway restrains hepatic oval cell proliferation, liver size, and liver tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8248–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912203107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lu L, et al. Hippo signaling is a potent in vivo growth and tumor suppressor pathway in the mammalian liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911427107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Song H, et al. Mammalian Mst1 and Mst2 kinases play essential roles in organ size control and tumor suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1431–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911409107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Johnson R, Halder G. The two faces of Hippo: targeting the Hippo pathway for regenerative medicine and cancer treatment. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:63–79. doi: 10.1038/nrd4161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen CL, Gajewski KM, Hamaratoglu F, Bossuyt W, Sansores-Garcia L, Tao C, Halder G. The apical-basal cell polarity determinant Crumbs regulates Hippo signaling in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15810–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yu J, Zheng Y, Dong J, Klusza S, Deng WM, Pan D. Kibra functions as a tumor suppressor protein that regulates Hippo signaling in conjunction with Merlin and Expanded. Dev Cell. 2010;18:288–99. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]