Abstract

Background

The current AJCC staging system may not accurately reflect survival in patients with HPV+OPSCC. The purpose of this study is to develop a system that more precisely predicts survival.

Methods

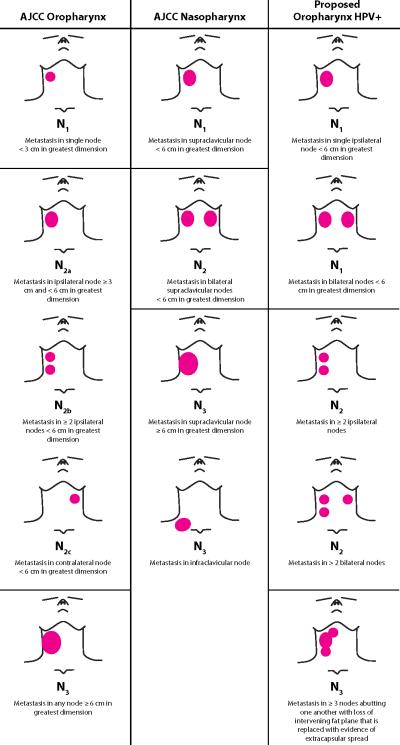

CT scans from 156 patients who underwent chemoradiation for advanced-stage OPSCC with >2years follow-up were reviewed. We modeled patterns of nodal metastasis associated with different survival rates. We defined HPV+N1 as a single node <6cm, ipsilaterally,contralaterally or bilaterally. HPV+N2 was defined as a single node ≥6cm or ≥2nodes ipsilaterally/contralaterally or ≥3nodes bilaterally. HPV+N3 was defined as matted nodes.

Results

There was no significant difference in DSS(p=0.14) or OS(p=0.16) by AJCC classification. In patients grouped by HPV+N1,HPV+N2,and HPV+N3 nodal classification, significant differences in DSS(100%,92%,55%,respectively,p=0.0001) and OS(100%,96%,55%,respectively,p=0.0001) were found.

Conclusions

A staging system with reclassification of size,bilaterality and matted nodes more accurately reflects survival differences in this cohort of patients. Review of the AJCC staging system with these criteria should be considered for HPV+OPSCC.

Keywords: Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Human Papillomavirus, American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System, Matted Nodes, Nodal Metastasis

Introduction

Patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) that are human papilloma virus (HPV) positive have a good prognosis despite most patients presenting with advanced stage III,IV disease. In a recent review of two clinical trials examining HPV status and survival in OPSCC, the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) reported that over 66% (478/721) of patients presented with advanced classification (N2 or N3) nodal disease. (1) Despite the advanced nodal classification at presentation, the strongest predictor of survival was HPV status, with a 3 year overall survival of 83.6% in this cohort. (1) The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 2010 guidelines currently stage regional metastasis in OPSCC based on size, number and laterally of lymph nodes involved with cancer. (2) While the staging system is continually updated every five years, the nodal staging system for OPSCC has not been modified since its inception in 1977. With the improved survival in patients with OPSCC who are HPV positive, the AJCC staging system may not accurately reflect survival in this virally associated disease.

Currently there are a number of clinical trials evaluating de-escalation in HPV positive patients. The logic around de-escalation is to treat patients less aggressively who present with more advanced stage disease. What if these patients are presenting at a more advanced stage because we are staging them with a system that does not apply to HPV+ patients? As we learn more about the molecular biology of cancers, one could imagine that we need to stage patients with a particular biology by one set of TMN criteria differently that another group of patients with a different biology despite the fact that the disease is arising from the same site. These types of adjustments have been made in other sites such as breast cancer with the BRCA gene. If the disease is biologically different perhaps at certain disease sites the disease will present differently based on TMN criteria.

Reconsideration of the staging system could refine risk stratification for OPSCC that may facilitate a return to the design of clinical trials based on risk stratification rather than the gross approach of de-escalation for patients who are presenting with a virally associated disease. We hypothesize that there are patterns of nodal metastasis in HPV positive OPSCC that are associated with varied survival outcomes more predictive than the current AJCC system.

Methods and Materials

Study population

This study was nested in a prospective phase II clinical trial (UMCC 02-021) designed to evaluate the toxicity and efficacy of weekly concomitant carboplatin, paclitaxel and intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for advanced stage (III,IV) OPSCC between 2003 and 2010. Patients were eligible for this study if they presented with previously untreated, AJCC nodal classification N1, N2, or N3, pathologically confirmed squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx who were HPV positive. Staging was performed in accordance with the 2010 American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system with clinical exam, direct laryngoscopy in the operating room and computed tomography (CT) scan and/or computed tomography/positron emission tomography (CT/PET). Patients were excluded if they had previous surgery or radiation therapy to the upper aerodigestive tract or neck imaging was not performed within 4 weeks of the initiation of treatment.

Population characteristics

One hundred fifty-six patients who met all inclusion criteria were identified and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were 215 patients who were initially screened for enrollment in this study. Ten patients were excluded because pretreatment imaging was unavailable for review and 19 patients were excluded because inadequate tissue available for analysis. There were 17 HPV negative patients and 13 patients classified AJCC N0 also excluded. There were 143 male patients and the mean age of the cohort was 56.1 years. The frequencies of involved subsites were 45% (70/156) base of tongue, 54% (84/156) tonsil, 1% (2/156) posterior pharyngeal wall. There were 30% (47/156) who had T4 tumors. Tobacco status was defined categorically as never, prior [quit greater than 6 months prior to diagnosis], or current use of cigarettes, cigars, pipe, chewing tobacco, snuff or snus. There were 50 never tobacco users, 56 prior tobacco users, and 50 current tobacco users.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Entire Cohort

| Characteristics | Entire Cohort n=156 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | mean (sd) | 56.3 |

| Sub-Site | BOT | 45% (70) |

| Tonsil | 54% (84) | |

| Posterior Pharyngeal Wall | 1% (2) | |

| Overall Stage | III | 7% (11) |

| IV | 93% (145) | |

| T stage | T1 | 20% (31) |

| T2 | 37% (57) | |

| T3 | 13% (21) | |

| T4 | 30% (47) | |

| N stage | N1 | 9% (14) |

| N2a | 8% (13) | |

| N2b | 42% (66) | |

| N2c | 25% (39) | |

| N3 | 15% (24) | |

| Tobacco Status | Never | 32% (50) |

| Prior | 36% (56) | |

| Current | 32% (50) | |

Tissue microarray and immunostaining

A tissue microarray (TMA) was constructed for 146/156 patients from pretreatment biopsies of the primary tumor by a previously described method. (3) There were 10 patients who did not have adequate tissue for TMA construction, therefore, single slides were made from paraffin embedded tissue samples and stained concurrently with the TMA. Separate cores were taken for DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis.

Staining for p16 was performed per protocol supplied by the kit (CINtec p16INK4a Histology Kit; mtm Laboratories, Westborough MA). Antibody binding was scored by a pathologist (JBM), using a continuous scale (ie, 10%, 30%, 90%, etc.) for the proportion of p16-positive tumor cells in each core or slide and percentage scored was broken down into a quartile scale of 1 to 4: 1 was less than 5%; 2, 5% to 20%; 3, 21% to 50%; and 4, 51% to 100% tumor staining. Intensity was scored as 1 equal to no staining; 2, low intensity; 3, moderate; and 4, high intensity. Scores for multiple cores from each patient were averaged. Staining for p16 was considered positive when >75% of tumor cells demonstrated strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining or >2 intensity.

Isolation of DNA from cored tissue samples was performed using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA concentration and purity were confirmed via NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). HPV status was determined by an ultra-sensitive method using real-time competitive polymerase chain reaction and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectroscopy with separation of products on a matrix-loaded silicon chip array, as described by Tang et al. (4)

HPV status was determined by the combination of immunohistochemistry, and/or PCR , and was considered positive if p16 staining was positive or when p16 staining was unavailable, then PCR assay was positive. Table 2 shows the five patients with discordances between p16 staining and PCR assay results. The two patients who were p16 negative but PCR assay positive were considered HPV negative and excluded. The pathologist was blinded to the clinical outcome.

Table 2.

Patients with Discordances between p16 Staining and PCR Assay Results

| Patient | PCR Assay Results | p16 Immunostain Proportion | HPV Status for Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Negative | 4 | Positive |

| 2 | Negative | 4 | Positive |

| 3 | HPV16 | 0 | Positive |

| 4 | Negative | 4 | Positive |

| 5 | HPV16 | 0 | Positive |

p16 Immunostain Proportions: 1= <5%, 2=5-20%, 3=21-50%, 4=51-100%

Patients are considered p16 positive if there is >5% staining pattern present

Treatment protocol

Radiation was given 5 days per week. The prescribed doses were 70 Gy at 2.0 Gy per fraction to gross disease and 59–63 Gy at 1.7–1.8 Gy per fraction to lowand high-risk subclinical regions, respectively, delivered concomitantly according to published methods. (5,6) Chemotherapy consisted of weekly carboplatin (AUC 1) intravenous over 30 minutes and paclitaxel 30 mg/m2 intravenous over 1 hour. Hydration and antiemetics were administered according to the standard of care.

Pretreatment imaging

Pretreatment CT or CT/PET scans obtained within four weeks of starting therapy were reviewed by a neuroradiologist (MI). Primary tumor site and size, distance of the primary tumor from the midline, and encasement of the carotid artery by the primary tumor were recorded. The size (largest two dimensions) and distribution (level I-V) of each lymph node was recorded for each level of the neck. AJCC N3 disease was defined clinically as a lymph node or group of lymph nodes greater than six centimeters. Matted nodes were defined as three nodes abutting one another with loss of intervening fat plane that is replaced with evidence of extracapsular spread with imaging. We have previously reported that matted nodes are predictive of a poor prognosis independent of age, T classification, HPV, EGFR and smoking status. (7) Extracapsular spread (ECS) was defined with imaging as loss of the sharp plane between the capsule of the lymph node and the surrounding fat.

Modeling Process

The first model we selected was a known model of poor prognosis in nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma defined by the 7th edition AJCC. Briefly, NasoN1 was defined as unilateral regional metastasis, all <6cm and above the supraclavicular fossa. NasoN2 was defined as bilateral regional metastasis, all < 6cm and above the supraclavicular fossa. NasoN3 was defined as node(s) greater than 6cm or regional metastasis in the supraclavicular fossa.

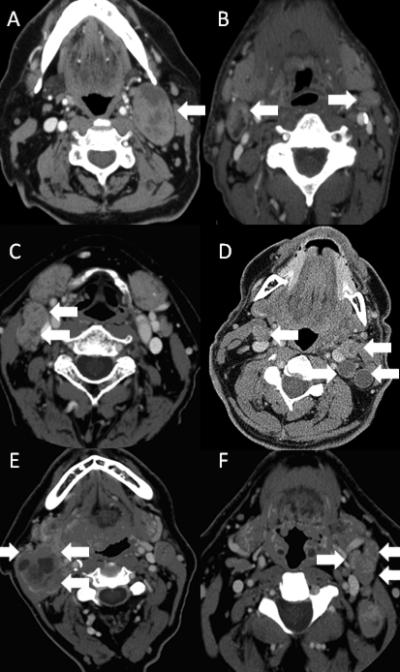

The second modeling approach selected patients with the worst prognosis. This group was defined by patients with matted nodes, as our previous work has shown, this cohort has a poor prognosis due to the development of distant metastasis. (7) We then determined that patients with single nodal metastasis, despite the conventional size criteria or laterality (ipsilateral, contralateral or bilateral) appeared to have an improved prognosis. This included patients previously determined to have AJCC N1, N2a, or N2c with only a single node on each side of the neck. Finally, there was a group of patients that had a node greater than 6cm or had greater than two nodes ipsilaterally/contralaterally or greater than 3 nodes bilaterally that were not matted who had an intermediate prognosis as compared to patients with matted nodes or those with a single nodal metastasis. Therefore, we defined HPV+N1 as patients who had a single node <6cm, ipsilaterally, contralaterally or bilaterally (AJCC N1, N2a or N2c with a single node bilaterally). We defined HPV+N2 as patients who had a single node ≥ 6cm or ≥2 nodes ipsilaterally or contralaterally or >3 nodes bilaterally (AJCC N2b, N2c with ≥3 nodes, or N3, without matted nodes). We defined HPV+N3 as patients with matted nodes. Table 3 summarizes the nodal classifications for each of the different systems. Radiographic examples for each of the HPV + N classifications are displayed in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1. Computed Tomography Scans Demonstrating Examples of HPV+N Staging System.

Panels A and B show examples of patients who were categorized as HPV+N1. Panel A shows a single metastatic node less than 6 centimeters in level II of the left neck (arrow). Panel B shows bilateral level 2 nodal metastasis without other node involvement (arrows). Panels C and D show examples of patients who were categorized as HPV+N2. Panel C shows two metastatic nodes in level II of the right neck (arrows). Panel D shows bilateral level 2 nodal metastasis with more than one metastatic node on the left (arrows). Panels E and F show examples of patients who were categorized as HPV+N3. Panel E and F show three nodes (arrows) with loss of intervening fat plane that is replaced with extracapsular spread (matted nodes).

Statistical analysis

The outcomes of interest were overall survival [OS] and disease-specific survival [DSS]. The start point for survival estimates was defined as date of diagnosis. An overall survival event was defined as death from any cause; disease specific survival events were defined as a death from cancer, deaths from other causes were censored at the date of death. Variables studied included age, gender, disease sub-site, AJCC T classification, AJCC N classification, AJCC Nasopharyngeal N classification, tobacco status, and the HPV+ N classification system presented above. Tobacco status was defined categorically as never, prior [quit greater than 6 months ago], or current use. The three different staging systems were also compared based on their performance in a Cox proportional-hazards model using the Akaike information criterion (AIC), where smaller values are considered better. Written informed consent was obtained in all patients, and this research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan.

Results

The 3-year overall survival, disease specific survival, and disease free survival for the entire cohort were 85%, 88%, and 77%, respectively, with a median follow-up of 42 months. The proportion of patients in the AJCC staging system, the NasoN staging system and the HPV+N staging system are stratified by T classification and shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Number of Patients within each Nodal System Stratified by T Classification

| AJCCN1 | AJCCN2 | AJCCN3 | NasoN1 | NasoN2 | NasoN3 | HPV+N1 | HPV+N2 | HPV+N3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 5 | 22 | 4 | 21 | 2 | 8 | 11 | 14 | 6 | 31 |

| T2 | 4 | 43 | 10 | 37 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 37 | 8 | 57 |

| T3 | 1 | 18 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 11 | 4 | 21 |

| T4 | 4 | 35 | 8 | 19 | 16 | 12 | 13 | 17 | 17 | 47 |

| Total | 14 | 118 | 24 | 88 | 34 | 34 | 42 | 79 | 35 | 156 |

AJCC – American Joint Committee on Cancer

Naso – Nasopharnygeal

HPV – Human Papillomavirus

There were a total of 34 recurrences in the cohort. There were 3 patients with local recurrences with 1/3 successfully salvaged and 4 patients with isolated regional recurrences with ¾ successfully salvaged. There was 1 patient with a local and regional recurrence who was successfully salvaged, but later died of other causes. There were 20 patients who developed distant metastasis, 15 died of disease, 4 are alive with disease and 1 patient who underwent wedge resection of the lung who is free of disease. There were 4 patients with a local recurrence and distant metastasis, 1 patient with a regional recurrence and distant metastasis, and 1 patient with a local, regional and distant recurrence, all of whom died of disease.

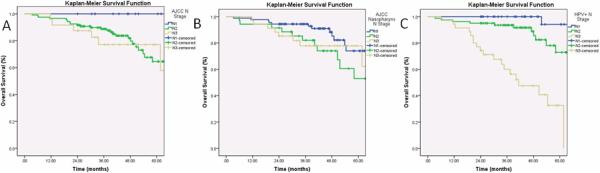

N classification by current AJCC staging system

When stratifying by the current AJCC nodal classification system, there was no difference in the OS by the log-rank test (p=0.16, Figure 2a). The 3-year OS stratified by the current AJCC nodal classification system for N1, N2 and N3 nodal disease was 100%, 86%, and 74%, respectively. The log-rank detects differences when comparing all three (N1, N2, N3) survival curves and does not detect differences between individual groups. Therefore, N stages were compared in a pair-wise fashion. There were no significant differences in OS when comparing patients with N1 and N2 (p=0.063) as well as N2 and N3 nodal disease (p=0.12). There was a significant difference when comparing N1 and N3 nodal disease (p=0.047).

Figure 2. Overall Survival Curves of the Entire Cohort Stratified by the American Joint Committee on Cancer Oropharyngeal Staging System, Nasopharyngeal (NasoN) Staging System, and the HPV N Positive (HPV+N) Staging System.

Figure 2a shows the OS of the entire cohort stratified by the AJCC staging system. There were no significant differences in OS when comparing patients with N1 and N2 (p=0.063) as well as N2 and N3 nodal disease (p=0.12). Figure 2b shows the OS of the entire cohort stratified by the NasoN staging system. There was no significant difference in OS when comparing NasoN2 and NasoN3 nodal disease (p=0.61). Figure 2c shows the OS of the entire cohort stratified by the HPV+N staging system. There were significant differences in OS when comparing patients with HPV+N1 and HPV+N2 (p=0.03) as well as HPV+N2 and HPV+N3 nodal disease (p=0.0001).

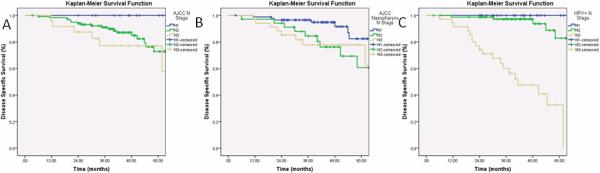

There was no significant difference in DSS when stratifying by the current AJCC nodal classification system by the log-rank test (p=0.14, Figure 3a). The 3-year DSS stratified by the current AJCC nodal classification system for N1, N2 and N3 nodal disease was 100%, 89%, and 74%, respectively. There were no significant differences in DSS when comparing patients with N1 and N2 (p=0.12) as well as N2 and N3 nodal disease (p=0.30). There was a significant difference when comparing N1 and N3 nodal disease (p=0.047). While the AJCC system demonstrates differences between patients with N1 and N3 disease, the DSS of all N classifications in this system is still above 60% at 5 years.

Figure 3. Disease Specific Survival Curves of the Entire Cohort Stratified by the American Joint Committee on Cancer Oropharyngeal Staging System, Nasopharyngeal (NasoN) Staging System, and the HPV N Positive (HPV+N) Staging System.

Figure 3a shows the DSS of the entire cohort stratified by the staging AJCC system. There were no significant differences in DSS when comparing patients with N1 and N2 (p=0.12) as well as N2 and N3 nodal disease (p=0.30). Figure 3b shows the DSS of the entire cohort stratified by the NasoN staging system. There was no significant difference in DSS when comparing NasoN2 and NasoN3 nodal disease (p=0.96). Figure 3c shows the DSS of the entire cohort stratified by the HPV+N staging system. There were significant differences in DSS when comparing patients with HPV+N1 and HPV+N2 (p=0.05) as well as HPV+N2 and HPV+N3 nodal disease (p=0.0001).

The 3-year DFS stratified by the current AJCC nodal classification system for N1, N2 and N3 nodal disease was 100%, 77%, and 53%, respectively. There were no significant differences in DFS when comparing patients with N1 and N2 (p=0.063) or N2 and N3 nodal disease (p=0.073). There was a significant difference when comparing N1 and N3 nodal disease (p=0.011).

N classification by current Nasopharyngeal AJCC staging system

When stratifying by the NasoN classification system, there was no significant difference in the OS by the log-rank test (p=0.12, Figure 2b) The 3-year OS stratified by NasoN1, NasoN2, and NasoN3 nodal stage disease was 92%, 80%, and 74%, respectively. There was a significant difference is OS when comparing patients with NasoN1 and NasoN2 (p=0.044). There was no significant difference in OS when comparing NasoN2 and NasoN3 nodal disease (p=0.61).

There was a significant difference in DSS when stratifying by the NasoN classification system by the log-rank test (p=0.03, Figure 3b). The 3-year DSS stratified by NasoN1, NasoN2, and NasoN3 nodal stage disease was 95%, 83%, and 74%, respectively. There was a significant difference is DSS when comparing patients with NasoN1 and NasoN2 (p=0.015). There was no significant difference in DSS when comparing NasoN2 and NasoN3 nodal disease (p=0.96). The NasoN staging system demonstrates a difference between patients with NasoN1 and NasoN2 disease, but the DSS of all N classifications in this system is still above 60% at 5 years.

The 3-year DFS stratified by NasoN1, NasoN2, and NasoN3 nodal stage disease was 84%, 73%, and 59%, respectively. There were no significant differences in DFS when comparing patients with NasoN1 and NasoN2 (p=0.06) or when comparing NasoN2 and NasoN3 nodal disease (p=0.41). There was a significant difference is DFS when comparing patients with NasoN1 and NasoN3 (p=0.004).

N classification by new HPV+ staging system

When stratifying by the HPV+N staging system, there was a significant difference in the OS by the log-rank test (p=0.0001, Figure 2c) The 3-year OS stratified by HPV+N1, HPV+N2, and HPV+N3 nodal stage disease was 100%, 92%, and 55%, respectively. More importantly, there were significant differences in OS when comparing patients with HPV+N1 and HPV+N2 (p=0.03) as well as HPV+N2 and HPV+N3 nodal disease (p=0.0001).

There was a significant difference in DSS when stratifying by HPV+N Staging system (p=0.0001, Figure 3c). The 3-year DSS stratified by HPV+N1, HPV+N2, and HPV+N3 nodal stage disease was 100%, 96%, and 55%, respectively. More importantly, there were significant differences in DSS when comparing patients with HPV+N1 and HPV+N2 (p=0.05) as well as HPV+N2 and HPV+N3 nodal disease (p=0.0001). This new system demonstrates significant differences between each N classification, and identifies a group of patients with extremely poor survival.

The 3-year DFS stratified by HPV+N1, HPV+N2, and HPV+N3 nodal stage disease was 100%, 88%, and 30%, respectively. There were significant differences in DFS when comparing patients with HPV+N1 and HPV+N2 (p=0.013) as well as HPV+N2 and HPV+N3 nodal disease (p=0.0001). There was a significant difference is DFS when comparing patients with HPV+N1 and HPV+N3 (p=0.0001) nodal disease.

The three different classification systems were also compared based on their performance in a Cox proportional-hazards model using the Akaike information criterion (AIC), where smaller values are considered better. HPV+ N classification had the best performance in models for DSS (AIC 171.4) compared to the current AJCC N classification (AIC 216.7) and nasopharyngeal AJCC N classification (211.8). There is no p value associated with type of measure, rather this is a “goodness of fit” model.

Discussion

In this HPV positive oropharyngeal cohort with N positive disease, we were able to demonstrate improved risk stratification for the nodal classification system. This finding suggests that further examination of the nodal classification in the AJCC staging system with these criteria should be considered for patients with HPV positive cancer.

In a recent prospective trial, Ang and colleagues examined “bulk of disease” in patients with OPSCC. (1) This was defined through the AJCC staging system as N2B, N2C or N3 disease, and these patients were considered to by higher risk for a disease specific event. We recently have examined the prognostic implications of different patterns of nodal metastasis, and have determined that patients with matted nodes, defined as three nodes abutting one another with loss of intervening fat plane that is replaced with radiologic evidence of extracapsular spread, have a poor prognosis independent of other known prognostic factors (T classification, EGFR expression, smoking status).(7) Therefore this may by a more accurate way of determining bulk of disease and defines a high risk group with a poor prognosis. Alternatively, the high incidence of other nodal metastatic patterns (AJCC N1, N2A, N2C with a single node) may not portend as poor a prognosis in this patient population.

The current nasopharyngeal (NasoN) nodal classification system was first developed by Ho in 1978 (8) and later modified by the AJCC. (2) It has been externally validated to predict prognosis in nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. When applying this system to our cohort of patients, NasoN did not predict prognosis. While it was able to stratify patients with unilateral versus bilateral neck metastasis (NasoN1 vs NasoN 2), supraclavicular nodal metastasis and nodal metastasis >6cm (NasoN3) was not a poor prognostic factor. In addition, this system did not identify a patient group with a poor prognosis (5 year survival of all groups >60%).

Our new system takes into account both HPV status and pattern of nodal metastasis. HPV status has been identified the single most important prognostic factor in OPSCC (greater than smoking, T and N classification) (1,7,10), and clinical trials are underway to de-escalate therapy in this cohort of patients. It is important during the de-escalation efforts that risk stratification is properly applied to identify patients at risk for treatment failure that could be placed at increased risk of partial response or recurrence by introducing less aggressive treatment regimens. Patients in the HPV+N3 group had a 3 year DSS of 55%, and might be considered for exclusion or stratification in such de-escalation trials.

The limitations of this study include a small sample size treated under a single protocol (other protocols may yield different outcomes). Further expansion and validation of these data is necessary to support a broad change in N classification criteria.

In conclusion, a nodal classification system based on reclassification of size, bilaterality and matted nodes more accurately reflects survival differences in this cohort of patients with OPSCC. A larger review of the nodal classification in the AJCC staging system with these criteria should be considered for patients with HPV positive OPSCC.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: P50 CA97248 NIH NCI NIDCR SPORE

Footnotes

This work was presented as an oral presentation at the 8th International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer in Toronto, ON.

Conflicts of interest and financial disclosures: None

References

- 1.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 1;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. Epub 2010 Jun 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. (7th Edition) 2010 ISBN: 978-0-387-88440-0. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar B, Cordell KG, Lee JS, Worden, et al. EGFR, p16, HPV Titer, Bcl-xL and p53, sex, and smoking as indicators of response to therapy and survival in oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jul 1;26(19):3128–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7662. Epub 2008 May 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang AL, Hauff SJ, Owen JH, et al. UM-SCC-104: a new human papillomavirus-16-positive cancer stem cell-containing head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell line. Head Neck. 2012 Oct;34(10):1480–91. doi: 10.1002/hed.21962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng FY, Kim HM, Lyden TH, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy of head and neck cancer aiming to reduce dysphagia: early dose-effect relationships for the swallowing structures. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007 Aug 1;68(5):1289–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.02.049. Epub 2007 Jun 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng FY, Kim HM, Lyden TH, et al. Intensity-modulated chemoradiotherapy aiming to reduce dysphagia in patients with oropharyngeal cancer: clinical and functional results. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Jun 1;28(16):2732–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6199. Epub 2010 Apr 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spector M, Gallagher K, Ibrahim M, et al. Matted Nodes: Poor Prognostic Factor in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Independent of HPV and EGFR Status. Head Neck. 2012 Jan 13; doi: 10.1002/hed.21997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho JHC. Stage classification of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a review. In: De The G, Eto Y, editors. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: etiology and control. IARC Scientific Pub. No. 20. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 1978. pp. 99–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper JS, Cohen R, Stevens RE. A comparison of staging systems for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 1998 Jul 15;83(2):213–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klozar J, Kratochvil V, Salakova M, et al. HPV status and regional metastasis in the prognosis of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008 Jul;265(Suppl 1):S75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0557-9. Epub 2007 Dec 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]