Abstract

Background

Numerous disease modifying drugs for osteoarthritis (DMOADs) are under investigation. However, patients’ preferences for drugs to prevent progression of OA are not known. The objective of this study was to quantify patient preferences for potential DMOADs.

Methods

We administered a conjoint analysis survey to 304 patients attending outpatient general medicine and specialty clinics. All patients seated in the waiting rooms were asked if they would participate in a survey to elicit opinions about arthritis treatments. We performed simulations to estimate preferences for four options to prevent worsening of knee OA: Best Case (pill, highest benefit, lowest risk, lowest cost), Worst Case (infusion, lowest benefit, highest risk, highest cost), Moderate Subcutaneous Injection (injection, lowest benefit, mid-level risk, mid-level cost), and Moderate Infusion (same as previous except administered by infusion).

Results

Subjects’ median age was 57 years; 55% were female and 69% were Caucasian. Segmentation analyses revealed 4 patterns of preferences. A small minority (5%) who do not want to perform subcutaneous injections and will only consider DMOADs under the Best-Case scenario. Approximately 20% are risk sensitive and are willing to take DMOADs under the Best-Case scenario, but start rejecting these medications as risk increases. A significant number reject DMOADs under all conditions (16.4%); however, the largest segment (59.2%) has a strong preference for DMOADs across all scenarios.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that a significant percent of a non-selected outpatient population might be willing to accept at least a moderate degree of risk in order to prevent worsening knee OA.

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common cause of knee pain and lower extremity disability in older adults (1). Persons with knee OA have significantly lower quality of life scores in all domains compared to age-matched controls (2). This disease affects approximately 27 million Americans and costs $10.3 billion and $185.5 billion in indirect and direct costs respectively (3). The impact and costs related to knee OA are expected to continue to rise as the number of older adults in the population increases.

The effect sizes of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment options for knee OA are modest (4). Total knee arthroplasty is highly effective, however, recent data have shown that up to 20% of patients are dissatisfied after the procedure (5–8), and not all patients want (9), or are eligible for surgery. Moreover, TKA imposes limitations on several sports-related activity which may be important to more active individuals. Given the significant impact of OA and the limitations of both medical and surgical options, there is strong interest in developing disease modifying drugs (DMOADs) to prevent or minimize the pain and disability due to this disease.

At present, there are no Food and Drug Administration approved DMOADs (10). Numerous therapeutic strategies aimed at inhibiting synovial inflammatory mediators, cartilage degradation, and subchondral bone remodeling or promoting cartilage repair are under investigation. Demonstrating the efficacy of these agents is expected to be challenging as detailed in a recent report developed in response to a request by the Commissioner’s Office of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (11). This document summarizes the current methodological standards for conducting randomized clinical trials (RCTs) involving DMOADs and makes a series of recommendations for future research (12–16). It emphasizes the importance of ensuring the adequate safety of new therapies as well as an acceptable balance between the risks and benefits of potential DMOADs (14, 16). Missing from the FDA report, however, is the patient’s perspective. Given that the decision to ultimately use a DMOAD will depend on patients’ values, an understanding of patients’ preferences for potential DMOADs should inform 1) which treatment options are included in RCTs, 2) the choice of outcomes used to demonstrate efficacy, and 3) what constitutes an acceptable safety profile for a specified expected benefit.

Patients’ treatment preferences for OA are generally sought at the individual level in the form of testimonials (e.g. Food and Drug Administration hearings for the approval of new drugs) or in the aggregate to describe preferences of patient populations as a whole or by specific demographic or clinical subgroups (17–20). However, these approaches do not reveal whether the importance that patients attach to specific medication characteristics and their willingness to try a DMOAD cluster into distinct segments of the population that are similar within themselves but statistically different from other groups. Segmentation analysis allows one to subdivide a large population into meaningful segments which vary in their demands, or in this case, their treatment preferences. This approach has been successfully used to reveal clusters of consumer preferences for goods and more recently to reveal varying patterns of preferences for public health interventions [e.g., to decrease bullying (21), increase booster seat use (22), and increase uptake of mosquito control strategies (23)], however, few data are available to support this approach as a means to understanding patient variability in treatment preferences (24, 25).

The objectives of this study were to 1) quantify patient preferences for hypothetical DMOADs over a specified range of risks, benefits and costs using conjoint analysis and 2) determine the added value of latent class segmentation analysis in understanding the breadth of patients’ perspectives.

Methods

A research assistant-administered a paper and pencil survey to a convenience sample of 304 patients attending general medicine and subspecialty outpatient clinics affiliated with a large university medical center. The survey was administered prior to scheduled clinic appointments. Subjects were not compensated for their participation. Patients were recruited without regard to a known diagnosis of OA or their reported level of knee pain, because the criteria for DMOAD eligibility have not been defined. The presence/absence of knee pain was taken into account in the analyses.

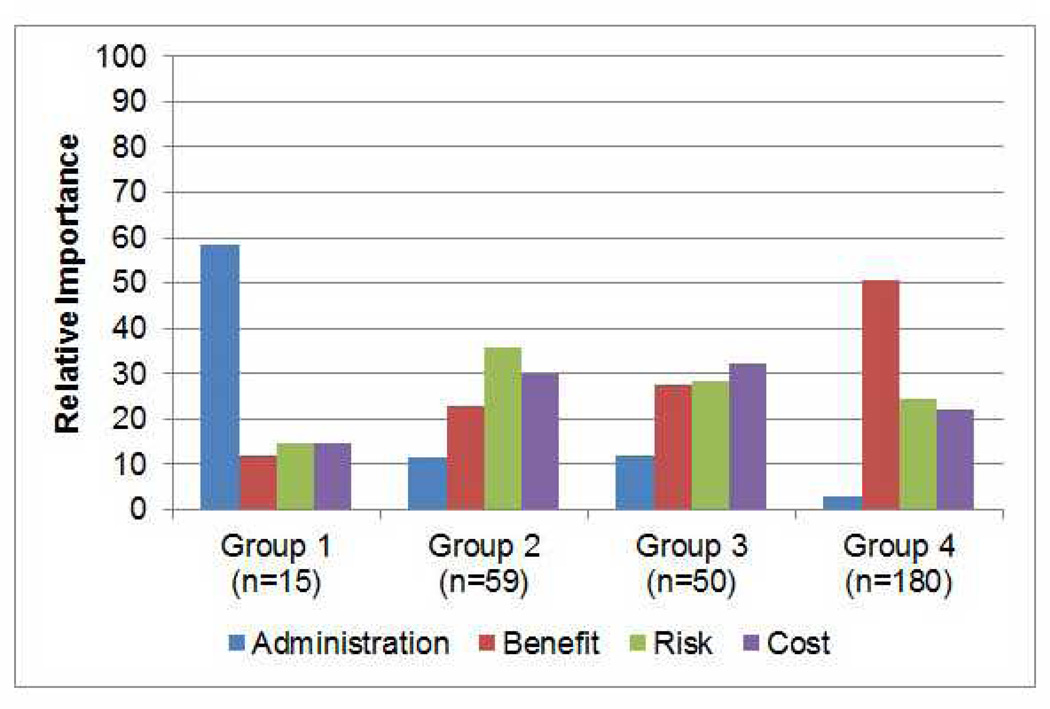

Preferences were ascertained using choice-based conjoint analysis (CBC). CBC is a computerized questionnaire which assesses preferences by asking respondents to choose a preferred option from a set of hypothetical alternatives (see example in Figure 1). Conjoint analysis assumes that each option is a composite of different characteristics, and that each characteristic represents one of a number of levels. Levels refer to the range of estimates for each characteristic. Respondents do not evaluate treatment alternatives directly. Preferences are calculated based on how participants value differences between competing options. Answers to respondent-specific questions allow the investigator to infer values for specific treatment characteristics and to predict which option most closely suits each participant’s individual preferences.

Figure 1.

Example of a Random Choice Task

If these were your only options, which would you choose?

The survey was designed using Sawtooth Software, SSI Web 8.0. It was composed of four attributes, each having three levels (detailed in Appendix A): (1) route of administration (pill taken once a day, weekly subcutaneous injection, monthly infusion), (2) expected benefit (prevents OA progression in 40%, 60%, or 80% of patients taking the medication), (3) risk of drug toxicity (mild: < 1 week and reversible; moderate: 1–2 weeks and requires treatment; serious: requires hospitalization), and (4) cost (easy, somewhat, hard to afford). The survey included an educational component describing all medication characteristics using lay terminology (Appendix A).

Each subject performed 12 random choice tasks each with three hypothetical medications and a “None” option (See example in Figure 1). Given the number of attributes (4) and the number of possible levels per attribute (3), the total number of possible combinations was 34=81. We therefore used the software’s complete enumeration strategy to construct the 12 choice sets. The complete enumeration method ensures that 1) each level is shown as few times as possible in a single task, 2) each level is shown approximately an equal number of times across the choice tasks, and 3) the level of one characteristic is chosen independently of the levels of other characteristics. The program was set to generate a design for 300 versions of the survey. The standard error for each level was 0.02 and the efficiencies reported were all 1.000.

In addition to the 12 choice sets where levels were assigned as per the above described strategy, we included two fixed tasks in which the investigators defined the options in the choice set in order to gauge the accuracy of the utility estimates. Both fixed tasks held route of administration and cost constant (pill and easy to afford, respectively). The first task also held benefit constant at 60% and increased the severity of side effects across the three choices presented. The second fixed task held the risk of side effects at mild and route of administration as a pill and decreased benefit across the three choices presented (from 80%, to 60% to 40%). The responses of the fixed tasks (i.e. hold out tasks) were not included in the simulations.

After the respondents completed the CBC survey, we collected demographic characteristics, frequency of knee pain (on a 5-point scale ranging from “Very Often” to “Never”), and report of physician diagnosed knee arthritis (Yes/No). The protocol was approved by the Yale Human Studies Research Program.

Statistical Analysis

For each respondent, utilities (zero-centered values) were calculated for each level of each attribute using Hierarchical Bayes (HB) modeling (Sawtooth CBC/HB system for hierarchical Bayes estimation version 4.0). HB modeling has the advantage that it can better incorporate heterogeneity between respondents’ choices (26). In HB modeling, the sample averages (prior information) are used to update the individual utilities in a number of iterations until the sample averages stop changing between iterations. After this convergence, the cycle is run several thousand more times and the estimates of each iteration are saved and averaged. Utilities were entered in SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and merged with the respondents’ characteristics. We calculated the percentage of importance that respondents assigned to each attribute by dividing the range of utilities for each attribute by the sum of the ranges and multiplying by 100. We subsequently performed Latent Class analysis (Sawtooth Software, SSI Web 8.0.) to examine whether preferences clustered by specific segments. Class solutions were replicated five times from random starting seeds.

We used Sawtooth Software Market Research Tools (SMRT) to estimate preferences separately for four hypothetical options versus no DMOAD (None): 1. Best-Case scenario: pill taken once a day, providing benefit in 80% of people, risk of mild drug toxicity, and easy to afford. 2. Worst-Case scenario: monthly intravenous infusion, providing benefit in 40% of people, risk of serious drug toxicity, and hard to afford. Scenarios 3 and 4 were moderate: Both were described as providing benefit in 60% of people, risk of moderate drug toxicity, and somewhat hard to afford. The only difference was that #3 was administered by subcutaneous injection and #4 by intravenous infusion. Market simulators were used to convert the raw utilities into preferences for specific options (27, 28). In this study, treatment preferences were generated using the randomized first choice model in which utilities are summed across the levels corresponding to each option and then exponentiated and rescaled so that they sum to 100. This model is based on the assumption that subjects’ prefer the option with the highest utility. The randomized first choice model accounts for the error in the point estimates of the utilities as well as the variation in each respondent’s total utility for each option. This model has been shown to have better predictive ability than other models (27).

Differences in patient characteristics across groups were examined using least square means and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables respectively. Variables significantly associated with preference were subsequently examined in a logistic regression model.

Results

304 subjects participated. Their median age was 57 years (range = 34–89); 55% were female; 69% Caucasian; 45% were currently employed; 37% were college graduates. 29% reported having knee pain often or very often; 28% reported having knee pain sometimes, and 30% reported having physician diagnosed knee arthritis. Approximately 10% of subjects chose an inferior option (i.e. an option with a greater risk of side effects or fewer benefits when all other characteristics were held constant) on the fixed choice tasks. 80.6% of subjects chose the dominant option in the first fixed task and 7.6% chose the “None” option. The results were similar for the second fixed task, in which 82.6% chose the dominant option and 6.3% chose “None”.

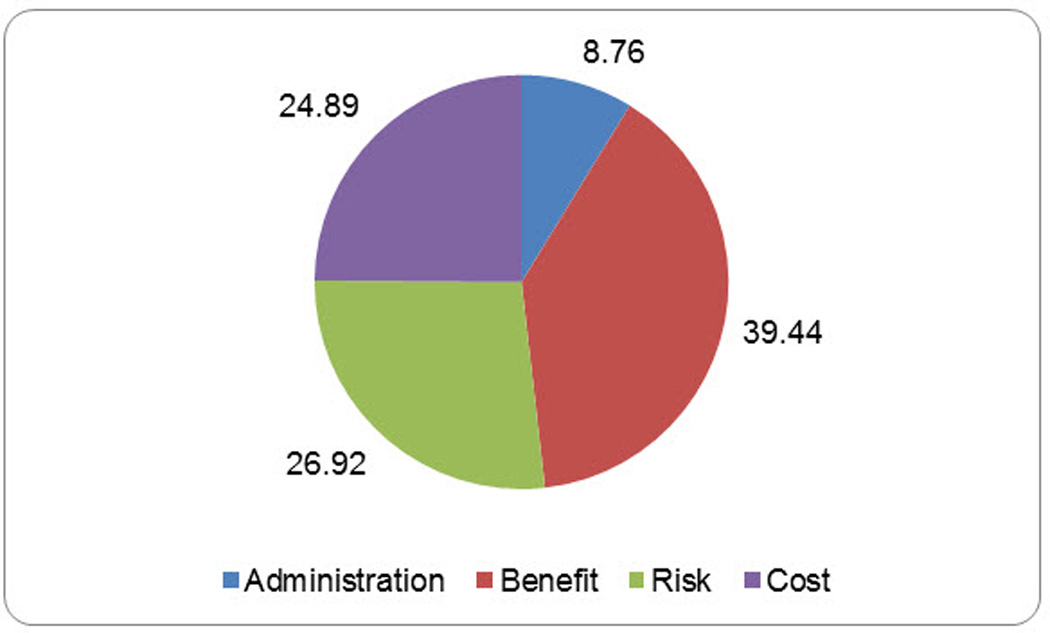

Results Using Aggregate Data

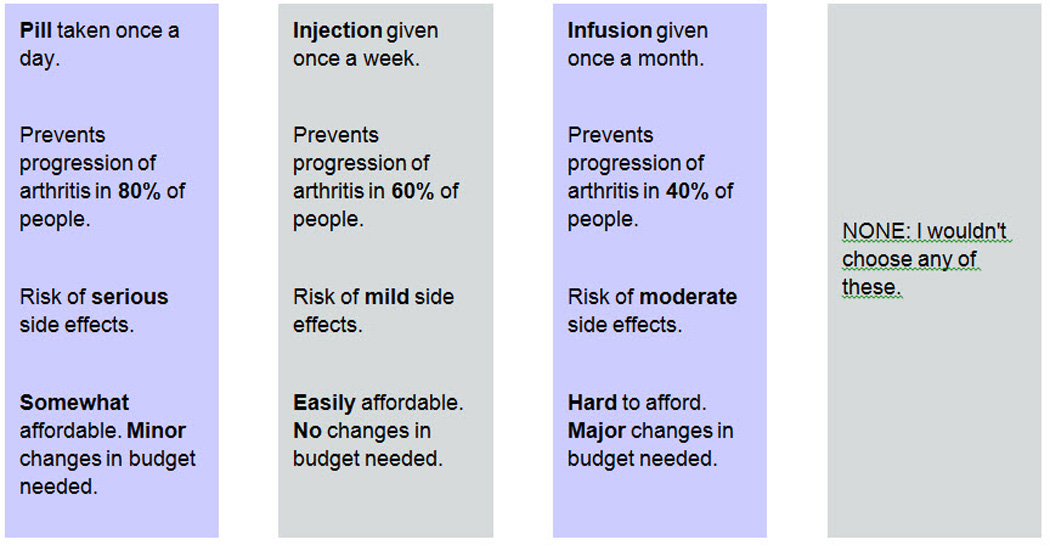

Figure 2 displays the relative importance of each attribute, given the levels included in the survey. Overall, potential benefit was the most influential factor (39.4%), followed by risk of side effects (26.9%), cost (24.5%) and route of administration (8.8%). Aggregate preferences are shown in the first column of Table 1. The majority of subjects (80%) were willing to try a DMOAD under the Best-Case scenario, i.e., an easy to afford pill, where 80% benefit and there is a risk of mild side effects. These results are consistent with the results of the second fixed task included in the survey. In the Worst-Case scenario (hard to afford infusion associated with a risk of serious side effects in which 40% are expected to benefit), 53% of subjects were willing to try a DMOAD. Approximately 65% of subjects were willing to try a “somewhat” affordable medication administered by injection or infusion that benefits 60% of people and is associated with a risk of moderate side effects (i.e., Scenarios 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Aggregate Relative Importances* of the Characteristics Studied

* Relative importances are specific to the attributes and levels include in the survey and sum to 100.

Table 1.

Percent Preferring Treatment (Vs. No treatment) for Each of Four Hypothetical Options by Group

| Scenario | Total (N=304) |

Group 1 (N=15) |

Group 2 (N=59) |

Group 3 (N=50) |

Group 4 (N=180) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best case | 80.2 | 99.4 | 98.2 | 18.4 | 89.8 |

| Worst case | 52.7 | 0.7 | 4.4 | 7.6 | 85.4 |

| Subcutaneous injection | 66.4 | 5.3 | 67.2 | 12.4 | 86.3 |

| Intravenous injection | 64.4 | 20.2 | 54.9 | 11.1 | 86.1 |

Best case: pill, 80% benefit, mild side effects, easy to afford

Worst case: Intravenous infusion, 40% benefit, serious side effects, hard to afford

Subcutaneous injection: Subcutaneous injection, 60% benefit, moderate side effects, somewhat hard to afford

Intravenous injection: Intravenous injection, 60% benefit, moderate side effects, somewhat hard to afford

Results Using Segmented Data

Segmentation analysis revealed four distinct groups based on segment size and interpretability as factors (Bayesian information criterion reported in Table 2). The relative importance for each attribute by group across the levels included in the survey is included in Figure 3. Group 1 (n=15) was comprised of a small number of subjects who were strongly influenced by route of administration. Subjects in Group 2 (n=59) were most strongly influenced by risk. Those in Group 3 (n=50) were not differentially influenced by benefit, risk or cost. Group 4 (n=180) comprised the majority of subjects who were focused primarily on potential benefit.

Table 2.

Summary of Replications

| Groups | Bayesian Information Criterion |

|---|---|

| 2 | 8844.26575 |

| 2 | 8844.27207 |

| 2 | 8844.26216 |

| 2 | 8844.27227 |

| 2 | 8844.27906 |

| 3 | 8639.10816 |

| 3 | 8639.10697 |

| 3 | 8639.11313 |

| 3 | 8639.10763 |

| 3 | 8685.31116 |

| 4 | 8528.71418 |

| 4 | 8529.27546 |

| 4 | 8528.71362 |

| 4 | 8527.70120 |

| 4 | 8528.71352 |

| 5 | 8528.90647 |

| 5 | 8542.47271 |

| 5 | 8517.26240 |

| 5 | 8426.20141 |

| 5 | 8542.48539 |

Figure 3.

Relative Importance of Each Characteristic Studied by Group

Preferences for DMOADs for each of the four scenarios are described in Table 1. Group 1 represent a small minority who are averse to performing subcutaneous injections and will only consider DMOADs under the Best-Case scenario. Group 2 members are risk sensitive. They are willing to take DMOADS under the Best-Case scenario, but will start rejecting these medications under more moderate scenarios, and will not consider DMOADs under the Worst-Case scenario. A significant number reject DMOADs under all conditions (Group 3); however members of the largest segment (Group 4) have a strong preference for DMOADs across all scenarios.

The demographic characteristics per group are described in Table 3. In unadjusted analyses, Black and less well educated subjects were more likely to be influenced by route of administration (p<0.001 and p=0.03, respectively) and those reporting having excellent or very good health status were more likely to reject DMOADs (p=0.006). We found no significant associations between knee pain or physician-diagnosed arthritis and preference for DMOADs. Those reporting having excellent or very good health status remained significantly more likely to belong to Group 3 (reject DMOADs) than other groups after controlling for ethnicity and level of education [Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI= 2.17 (1.14 – 4.12)] (Table 4).

Table 3.

Subject Characteristics by Group

| Group 1 (n=15) |

Group 2 (n=59) |

Group 3 (n=50) |

Group 4 (n=180) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 55 (12) | 57 (10) | 60 (11) | 59 (11) | 0.28 |

| Female, n (%) | 6 (40) | 29 (49) | 29 (58) | 103 (57) | 0.44 |

| Black, n (%) | 12 (80) | 16 (27) | 9 (18) | 35 (19) | <0.0001 |

| Excellent or very good health status, n (%) | 3 (20) | 20 (34) | 31 (62) | 81 (45) | 0.006 |

| Knee pain occurs often or very often, n (%) | 7 (47) | 15 (25) | 15 (30) | 52 (29) | 0.45 |

| Physician diagnosed knee arthritis, n (%) | 6 (40) | 15 (25) | 16 (32) | 53 (29) | 0.70 |

| At least some college, n (%) | 5 (33) | 38 (64) | 38 (76) | 118 (66) | 0.03 |

| Married, n (%) | 5 (33) | 25 (42) | 28 (56) | 95 (53) | 0.23 |

| Employed, n (%) | 3 (20) | 29 (49) | 21 (42) | 83 (46) | 0.22 |

Table 4.

Association between Subject Characteristicsand Unwillingness to Try a DMOAD

| Characteristic | Adjusted Odds Ratio* (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Excellent or very good health status | 2.17 (1.14 – 4.12) |

| At least some college | 1.54 (0.77 – 3.26) |

| Black | 0.93 (0.46 – 1.91) |

Logistic regression model including all four variables.

Discussion

We found that using a robust method of measuring preferences generated important information for understanding patterns of patient preferences for DMOADs. Our results suggest that a significant percent of people are willing to take a DMOAD over a range of risk-benefit ratios. Specifically, 59% were willing to try a parenteral medication which benefits 40% of patients and is associated with a serious risk of infection (probability 1 to 10%) requiring prolonged hospitalization. This finding reflects the significant impact of knee OA on functioning and quality of life (29, 30) and suggests that many patients might be willing to accept some degree of risk in order to prevent worsening knee OA.

The segmentation analysis reveals distinct patterns of preferences which clarify the breadth of patients’ perspectives. Specifically, we found that respondents can be categorized into four groups: A small percentage (5%) that is unwilling to consider any medication administered by injection, a moderate percentage (19%) that is risk sensitive, a second moderate percentage (16%) that is not willing to consider DMOADs under any circumstances, and a large percentage (59%) that is focused on preventing progression and is willing to try a DMOAD across all risk:benefit ratios presented. These patterns [aversion to self-administered injections, risk sensitive (i.e., willing to take medications but only across a specified range of benefits and risks), medication averse (in general reluctant to take medications), and medication favorable (primarily focused on potential benefits)] have strong face validity in that they mirror preferences commonly seen in clinical practice across diverse treatment conditions. The findings, if replicated in larger samples of patients with early knee OA, should inform the criteria by which regulatory agencies define what constitutes an acceptable balance for DMOADs.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine preferences for potential DMOADs. The strengths in this study lie in the methods used to quantify preferences and perform the segmentation analyses. In the aggregate, the responses reveal that the majority of people (80%) are willing to try a DMOAD under the Best case scenario, and that this percentage decreases to just over half as the risk:benefit ratio increases. The results generated from the segmentation analyses are much more informative as they demonstrate specific patterns of preferences and how prevalent each of these patterns is expected to be in the population of interest. Preferences were constructed using a robust method which relies solely on each patient’s evaluation of specific risks and benefits and is not biased based on brand name or product recognition.

There are also important limitations to this study. The results, while based on a reasonable sample size, do not reflect those of a population-based sample. Moreover, information on non-participants is not available. We did not include a specified level of knee pain as an eligibility criterion, because there may be a role for DMOAD in patients with a high risk for debilitating knee OA who are asymptomatic or have minimal levels of knee pain. Data regarding patient characteristics (such as severity of knee pain) are limited because of the relatively short amount of time we had to conduct the survey. However, one would expect even greater risk tolerance among patients with greater levels of knee pain. The attributes and levels included in the study were chosen to reflect a broad range of medication characteristics; still, the results can only be generalized to the characteristics included in the survey. Therefore, we cannot know, for example, whether the majority of subjects exhibiting a strong preference for a DMOAD (those belonging to Group 4) would be as willing to take a medication that benefited less than 40% of subjects. We did not include an attribute to differentiate between preferences for traditional pharmacologic agents and neutraceuticals (e.g., avocado soybean unsaponifiables). Whether subjects (especially those in Group 3) would be more willing to try a neutraceutical, or other non-pharmacologic options such as exercise or weight loss, should be examined in future studies. Approximately 10% of subjects chose an inferior option on the fixed choice task. This figure is consistent with other reports (33–35). We included the data from all respondents in the analyses, because 1) other choices may have been accurate, and 2) data suggests that participants frequently have a plausible rationale for choosing illogical options (36). While patient preferences are an essential element of decision making, data demonstrating whether preference predicts uptake and adherence are limited (37) and this inference requires future research.

Patients’ treatment preferences are known to vary significantly. This finding remains after taking into account expected differences due to access (such as cost), disease activity, and sociodemographic characteristics. As indicated by the estimates provided for the total study population, aggregating choice data may be misleading. Segmentation analysis of conjoint data generates more informative estimates which can be used to better understand and predict patterns of patients’ preferences and plan for future therapies to prevent progression of knee OA.

Significance and Innovation.

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of disability for which many disease modifying drugs (DMOADs) are currently under development.

To date, principles guiding the development of DMOADs are based solely on clinicians’ and researchers’ preferences.

Patients’ preferences should inform the research and development of DMOADS.

This is the first study to quantify patients’ preferences for potential new medications aimed at altering the progression of knee OA.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number AR060231-01 (Fraenkel). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Suter is supported in part by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Contract Number HHSM-500-2008-0025I/HHSM-500-T0001, Modification No. 000008. Dr. Cunningham is supported in part by the Jack Laidlaw Chair in Patient-Centered Health Care. Dr Hawker is supported by the F.M. Hill Chair in Academic Women’s Medicine.

Appendix

Each question that you will see will have 4 pieces of information:

The way the medication is taken

How well the medication works

The possible risks

The cost

The way the medication is taken:

In this survey medications can be taken in 1 of 3 ways:

As 1 pill taken once a day. You can assume the medication can be taken at any time during the day with or without food.

As an injection once a week. This is the same as the way diabetics give themselves insulin shots.

As an infusion once a month. You can assume that the infusion can be done in your doctor's office or in a clinic and that it would take 2 hours.

How well the medication works:

Again you will see 3 options. The medication will be described as either:

Preventing the progression of arthritis in 80% of people.

Preventing the progression of arthritis in 60% of people.

Preventing the progression of arthritis in 40% of people.

Preventing the progression of arthritis means that the medication prevents arthritis from worsening so that you can continue to maintain your quality of life and do the activities you enjoy.

The possible risks:

The risks will be described as either mild, moderate or serious.

Assume that for each case the side effects happen in 1% to 10% of people who take the medication.

Examples of mild side effects are mild rash, headache, or stomach upset. These side effects last less than 1 week, do not interfere with your normal lifestyle and go away without treatment.

Examples of moderate side effects are sinusitis or bronchitis. These side effects last between 1 and 2 weeks, sometimes can affect your lifestyle, and get better with treatment you can take at home (for example antibiotics).

Examples of serious side effects are bad infections, like pneumonia. These side effects can last more than 2 weeks, significantly impact your lifestyle and need to be treated in the hospital.

Cost:

Lastly you will also see information on cost. Here we are talking about the cost you need to pay (whether or not you have insurance). Cost will be described in terms of how easy it is to afford the medication and whether or not you need to make any changes in you budget in order to be able to pay for the medication

References

- 1.Jordan KP, Wilkie R, Muller S, et al. Measurement of change in function and disability in osteoarthritis: Current approaches and future challenges. Current Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:525–530. 10. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832e45fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briggs A, Scott E, Steele K. Impact of osteoarthritis and analgesic treatment on quality of life of an elderly population. Ann Pharmacotherapy. 1999;33:1154–1159. doi: 10.1345/aph.18411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotlarz H, Gunnarsson CL, Fang H, Rizzo JA. Insurer and out-of-pocket costs of osteoarthritis in the US: Evidence from national survey data. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3546–3553. doi: 10.1002/art.24984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Hochberg MC, et al. Osteoarthritis: New Insights. Part 2: Treatment approaches. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:726–737. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-9-200011070-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker PN, van der Meulen JH, Lewsey J, Gregg PJ. The role of pain and function in determining patient satisfaction after total knee replacement: Data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2007;89:893–900. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B7.19091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim TK, Chang CB, Kang YG, Kim SJ, Seong SC. Causes and predictors of patient's dissatisfaction after uncomplicated total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robertsson O, Dunbar M, Pehrsson T, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Patient satisfaction after knee arthroplasty: A report on 27,372 knees operated on between 1981 and 1995 in Sweden. Acta Orthopaedica. 2000;71:262–267. doi: 10.1080/000164700317411852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435. 2011-000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, et al. Determining the need for hip and knee arthroplasty: The role of clinical severity and patients' preferences. Med Care. 2001;39:206–216. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Felson DT, Brandt KD. Unresolved questions in rheumatology: Motion for debate: Osteoarthritis Clinical trials have not identified efficacious therapies because traditional imaging outcome measures are inadequate. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2748–2758. doi: 10.1002/art.38086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abramson SB, Dougados M, Berenbaum F, et al. http://www.oarsi.org/pdfs/publications_newsroom/2011/07282010_fda_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abramson SB, Berenbaum F, Hochberg MC, Moskowitz RW. Introduction to OARSI FDA initiative OAC special edition. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2011;19:475–477. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conaghan PG, Hunter DJ, Maillefert JF, Reichmann WM, Losina E. Summary and recommendations of the OARSI FDA Osteoarthritis Assessment of Structural Change Working Group. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2011;19:606–610. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan JM, Sowers MF, Messier SP, et al. Methodologic issues in clinical trials for prevention or risk reduction in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2011;19:500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reichmann WM, Maillefert JF, Hunter DJ, Katz JN, Conaghan PG, Losina E. Responsiveness to change and reliability of measurement of radiographic joint space width in osteoarthritis of the knee: A systematic review. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2011;19:550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strand V, Bloch DA, Leff R, Peloso PM, Simon LS. Safety issues in the development of treatments for osteoarthritis: Recommendations of the Safety Considerations Working Group. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2011;19:493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bozic KJ, Chiu V, Slover JD, Immerman I, Kahn JG. Patient preferences and willingness to pay for arthroplasty surgery in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:503.e2–506.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraenkel L, Bogardus ST, Jr, Concato J, Wittink DR. Treatment options in knee osteoarthritis: The patient's perspective. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1299–1304. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.12.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratcliffe J, Buxton M, McGarry T, Sheldon R, Chancellor J. Patients' preferences for characteristics associated with treatments for osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2004;43:337–345. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson CG, Chalmers A, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Klinkhoff A, Carswell A, Kopec JA. Pain relief in osteoarthritis: patients' willingness to risk medication-induced gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular complications. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1569–1575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunningham CE, Vaillancourt T, Rimas H, et al. Modeling the bullying prevention program preferences of educators: a discrete choice conjoint experiment. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009;37:929–943. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunningham CE, Bruce BS, Snowdon AW, et al. Modeling improvements in booster seat use: a discrete choice conjoint experiment. Accident Anal Prev. 2011;43:1999–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith RA, Barclay VC, Findeis JL. Investigating preferences for mosquito-control technologies in Mozambique with latent class analysis. Malaria J. 2011;10:200. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wittink MN, Morales KH, Cary M, Gallo JJ, Bartels SJ. Towards personalizing treatment for depression : Developing treatment values markers. The Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2013;6:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s40271-013-0003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waschbusch DA, Cunningham CE, Pelham WE, et al. A discrete choice conjoint experiment to evaluate parent preferences for treatment of young, medication naive children with ADHD. J Clin Child Adoles Psychol. 2011;40:546–561. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orme B. Hierarchical Bayes regression analysis: technical paper. Technical Paper Series. Sequim: Sawtooth Software; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huber J, Orme B, Miller R. The value of choice simulators. In: Gustafsson A, Herrmann AF, editors. Conjoint measurement. Fourth ed. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 347–362. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orme B. Getting started with conjoint analysis: strategies for product design and pricing research. Second ed. Madison: Research Publishers LLC; 2010. Market simulators for conjoint analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiBonaventura M, Gupta S, McDonald M, Sadosky A. Evaluating the health and economic impact of osteoarthritis pain in the workforce: results from the National Health and Wellness Survey. BMC Musculoskelet Di. 2011;12:83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook C, Pietrobon R, Hegedus E. Osteoarthritis and the impact on quality of life health indicators. Rheumatology Int. 2007;27:315–321. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults—United States, 2005. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:421–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevalence of doctor diagnosed arthritis and arthritis attributable activity limitation—United States, 2007–2009. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1261–1265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips KA, Maddala T, Johnson FR. Measuring preferences for health care interventions using conjoint analysis: An application to HIV testing. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1681–1705. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ratcliffe J, Buxton M. Patients' preferences regarding the process and outcomes of life-saving technology. An application of conjoint analysis to liver transplantation. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1999;15:340–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryan M, Hughes J. Using conjoint analysis to assess women's preferences for miscarriage management. Health Econ. 1997;6:261–273. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199705)6:3<261::aid-hec262>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan M, Watson V, Entwistle V. Rationalising the 'irrational': a think aloud study of discrete choice experiment responses. Health Econ. 2009;18:321–336. doi: 10.1002/hec.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilder CM, Elbogen EB, Moser LL, Swanson JW, Swartz MS. Medication preferences and adherence among individuals with severe mental illness and psychiatric advance directives. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:380–385. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.4.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]