Abstract

Affinity chromatography has become an important tool for characterizing biomolecular interactions. The use of affinity microcolumns, which contain immobilized binding agents and have volumes in the mid-to-low microliter range, has received particular attention in recent years. Potential advantages of affinity microcolumns include the many analysis and detection formats that can be used with these columns, as well as the need for only small amounts of supports and immobilized binding agents. This review examines how affinity microcolumns have been used to examine biomolecular interactions. Both capillary-based microcolumns and short microcolumns are considered. The use of affinity microcolumns with zonal elution and frontal analysis methods are discussed. The techniques of peak decay analysis, ultrafast affinity extraction, split-peak analysis, and band-broadening studies are also explored. The principles of these methods are examined and various applications are provided to illustrate the use of these methods with affinity microcolumns. It is shown how these techniques can be utilized to provide information on the binding strength and kinetics of an interaction, as well as on the number and types of binding sites. It is further demonstrated how information on competition or displacement effects can be obtained by these methods.

Keywords: Affinity microcolumns, High-performance affinity chromatography, Biointeraction analysis, Zonal elution, Frontal affinity chromatography, Ultrafast affinity extraction

1. Introduction

Biomolecular interactions make up an important component of the many pathways and responses that are present in living systems. These interactions include the binding of substrates and co-factors to enzymes, antigens to antibodies, proteins to proteins, and sugars to lectins, as well as the binding of small molecules such as hormones and drugs with transport proteins and receptors [1–4]. These interactions can determine the eventual activity, distribution, excretion, metabolism, and effects of a solute or biomolecule in the body. In addition, the binding of small molecules with proteins can determine the solubility of hydrophobic compounds and can be an important source of direct or indirect competition between different solutes with the same binding protein (e.g., drug–drug interactions) [5–12].

Various techniques can be employed for examining biomolecular interactions. These methods include X-ray crystallography, fluorescence spectroscopy, absorption spectroscopy, ultrafiltration, equilibrium dialysis, capillary electrophoresis, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) [5,6,10,13–27]. Two other, related methods that have seen increasing use in the study of biomolecular interactions are affinity chromatography and high-performance affinity chromatography (HPAC, also known as high-performance liquid affinity chromatography or HPLAC) [1–4,9,11,28–30]. These methods use a chromatographic column and support that contain an immobilized biologically related agent (e.g., a protein or receptor) as the stationary phase. This immobilized agent can then be used to study the binding of injected compounds to the column or as a probe to examine the interaction of an injected compound with another binding agent in the mobile phase [2,3]. Various types of columns and formats can be used in these experiments [1–3,9,11,31–33]. However, one topic that has been of growing interest in the analysis of biomolecular interactions is the use of affinity microcolumns for such work (i.e., columns containing affinity ligands and with volumes in the mid-to-low microliter range) [1,2,34–39].

This review examines the developments and applications that have appeared in the use of affinity microcolumns as related to the characterization of biomolecular interactions. First, the basic principles behind affinity chromatography and HPAC are described, especially as related to the use of these methods in investigating biomolecular interactions. The general types of affinity microcolumns that have been reported for binding studies are next considered. These microcolumns range from open-tubular capillaries and packed capillaries to small columns based on monoliths or particulate supports [2,4,40–55]. The various approaches that have been used with affinity microcolumns for binding studies are then discussed. This discussion includes various formats based on zonal elution and frontal analysis [1,2,11,31,34,50–59]. In addition, techniques such as peak decay analysis, split-peak analysis, ultrafast affinity extraction, and band-broadening measurements are discussed [2,11,31,34,55]. The principles behind each method are described, along with the advantages and possible limitations of these methods. Various examples are also provided to illustrate the use of these techniques with affinity microcolumns. These examples range from drug–protein interactions (including those involving chiral drugs), to antibody–antigen interactions, the binding of enzymes with inhibitors, and the interactions of lectins with sugars, among others.

1.1. Basic principles of affinity chromatography and HPAC

Affinity chromatography is a liquid chromatographic technique that uses a biologically related binding agent, or “affinity ligand”, as the stationary phase to separate or analyze sample components [3,60–64]. This stationary phase can be created by covalently attaching, entrapping, absorbing or in some other way immobilizing the affinity ligand to a chromatographic support [3,60,61]. This solid support and the stationary phase are placed within a column or capillary that can then be used for the purification, separation or analysis of targets capable of binding to the affinity ligand [28,61–70]. The retention and separation of a target from other sample components is based on the specific and reversible interactions that characterize many biological interactions, such as the binding of an antibody with an antigen or a hormone with a receptor [1–3,61–64]. If the interaction is strong (i.e., with an association equilibrium constant greater than 105–106 M−1), an elution buffer and a change in the pH, temperature, or mobile phase composition may be required to remove the target from the column [34,71,72]. If weaker binding is present (i.e., an association equilibrium constant of 105–106 M−1 or less), it may be possible to elute the target under isocratic conditions. This latter method is sometimes referred to as weak affinity chromatography (WAC) [29,30]. The variety of elution formats, immobilized ligands, and columns that can be used in affinity chromatography has made this method a valuable tool for the study of biomolecular interactions [1–3,31,51,57], as will be discussed in this review.

In any type of affinity chromatography, the support that is used for the immobilized affinity ligand should have low non-specific binding to sample components and yet be easy to modify for ligand attachment [60–64,73–76]. Traditional affinity chromatography typically employs relatively inexpensive supports and non-rigid materials with low-to-moderate efficiencies, such as agarose gels or other carbohydrate-based materials [3,62,63,73]. In the method of HPAC, which is the type of affinity chromatography utilized with most affinity microcolumns, the support is a material that has sufficient mechanical stability and efficiency for use in HPLC [3,9,61,64,73,74]. This type of support, in turn, tends to provide HPAC with better speed and precision than traditional affinity chromatography, along with greater ease of automation through the use of HPLC systems [1,4,59,61,73–76]. Possible supports for HPAC include particulate materials based on modified silica or glass, azalactone beads, and hydroxylated polystyrene media [1,3,61,73,74]. Various types of monolithic supports have also been considered for use in HPAC and affinity chromatography, such as those based on organic polymers, silica monoliths, cryogels and modified forms of agarose [4,73,75–82]. The recent interest in monoliths for these affinity-based separations is due to several useful features of these supports, including their rapid mass transfer properties, low back pressures, and ability to be made in a variety of shapes and sizes [4,73,75,76,79,82].

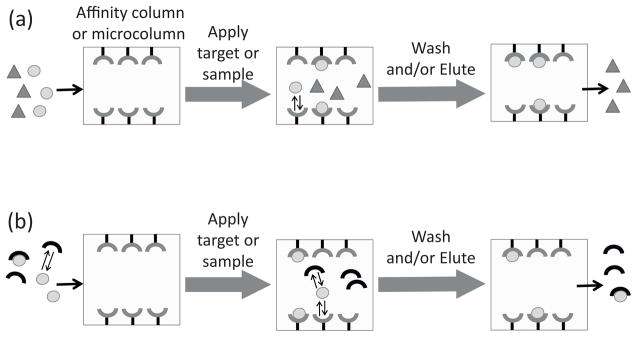

The use of affinity chromatography and HPAC for the study of biomolecular interactions is sometimes referred to as analytical affinity chromatography, quantitative affinity chromatography, or biointeraction chromatography [2,3,11,31,51–59,61,83]. This type of approach either examines the interaction of an applied target with the immobilized affinity ligand or uses the affinity ligand to examine interactions of the target with another binding agent in the mobile phase (see Fig. 1) [2,31,61]. A great deal of information can be obtained through such experiments. This information can include data on the number of interaction sites for the target with a binding agent, the equilibrium constants for this process, and the rate of the interaction [2,11,31,51,55,57,61,83,84]. Data can also be obtained on the types of competition the target may have with other compounds for interactions with the binding agent, and the structure and location of the sites that are involved in these interactions [31,57,84]. The specific approaches that can be used with affinity microcolumns to obtain this information are described later in this review.

Fig. 1.

Two general schemes for the use of HPAC and affinity chromatography to study biomolecular interactions based on (a) the binding of an applied target with the immobilized affinity ligand or (b) use of the affinity ligand to examine interactions of the target with another binding agent in solution.

1.2. Types of affinity microcolumns

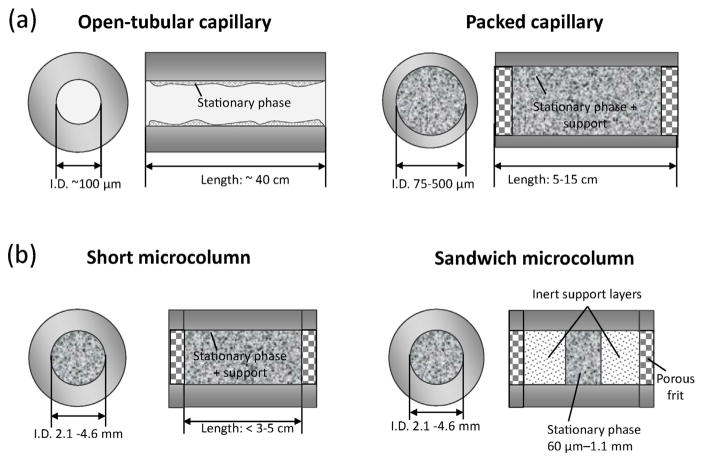

A reduction in column size has been of interest in the fields of HPLC and chromatographic separations for many years. This interest initially appeared due to some common limitations with traditional 10–25 cm × 4.6 mm i.d. HPLC columns, such as issues related to high backpressures, solvent consumption, and difficulties in working with small sample volumes [85]. To overcome these limitations, work began in the 1970s to reduce the size of columns in chromatographic systems and to produce various types of small-volume columns [86–89]. Examples of approaches that have been used specifically in HPAC and affinity chromatography to produce affinity microcolumns are shown in Fig. 2 [34–39].

Fig. 2.

Examples of affinity microcolumns that have been used for studying biomolecular interactions, including designs based on (a) open-tubular or packed capillaries and (b) short microcolumns or sandwich microcolumns.

The first approach for reducing the size of a chromatographic column is to decrease the column’s inner diameter, as is illustrated in Fig. 2(a). This change is usually accompanied by an increase in column length to maintain or provide high efficiency for the system while still giving an overall decrease in volume versus traditional columns. This approach may involve the use of either open-tubular capillary columns or packed capillary columns [85]. Open-tubular capillaries that have been used with affinity ligands for binding studies have generally had an inner diameter of 100 μm and lengths of 30–40 cm, giving total volumes of approximately 2–4 μL [35–37]. Packed capillaries that have been used with affinity ligands and binding studies have had an inner diameter of up to 0.5 mm and a length that ranges from 5 to 15 cm (volumes, 10–30 μL) [35–37,41,42,46–49,90–92].

There are several advantages to using the open-tubular or packed capillary columns in affinity-based binding studies. For instance, the flow rates applied to such columns are usually quite low (i.e., in the nL/min to μL/min range) and the efficiencies can be high, resulting in a significant reduction in mobile phase consumption and sample size requirements [85,93]. One potential disadvantage is that these capillary columns often require specialized equipment that is designed for work at low flow rates and high efficiencies (e.g., microbore or nano-HPLC systems) [41,43,85,93]. However, these columns are attractive for use with on-line detection by mass spectrometry, which can provide high sensitivity in detecting small amounts of targets and can be used to confirm the identity of a target in a mixture of applied compounds [94–96].

Another approach for decreasing the column size is to reduce the length of the column, as shown in Fig. 2(b). This type of design can be employed in separations that do not require high efficiencies, such as those based on simple adsorption/desorption mechanisms and selective binding for affinity separations involving moderate-to-high strength interactions [3,58,60,61,97]. Various types of short microcolumns based on particulate supports or monolithic materials have been developed for affinity separations and binding studies. These columns often have an inner diameter of 2.1 mm or smaller and lengths of 1–5 cm (i.e., volumes less than 35–175 μL). Other possible formats include affinity disks, with an inner diameter of 4.6 mm and lengths of 1–2 mm [80,98–100], or sandwich affinity microcolumns, with effective lengths as small as 60–250 μm and volumes of only 0.2–0.9 μL [101]. A few advantages of using these columns in binding studies are that they are easy to employ with traditional HPLC systems, and they require only a small amount of support and binding agent. This type of column is often capable of withstanding high flow rates, because of its low backpressure, and can provide sample residence times in the second to millisecond range [38,40,102].

One advantage to utilizing either type of affinity microcolumn is that they are compatible with a variety of detection approaches. These detection forms include absorbance, fluorescence and near-infrared fluorescence, chemiluminescence, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry, and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry [35–42,46–49,90,102]. The small volume of affinity microcolumns [42,43,103] also leads to a significant decrease in the amount of support and affinity ligand that are needed for binding studies when compared to more traditional affinity columns [80,97,101–104]. In a large number of cases, it is possible to reuse the same binding agent for many experiments, which further helps to improve the precision and to decrease the cost of this method [50,105,106].

2. Zonal elution and affinity microcolumns

2.1. Principles of zonal elution

Zonal elution is one of the most common formats in HPAC and affinity chromatography for studying biomolecular interactions. This method was first used with affinity columns in 1974 [107] and is based on the measurement of peak retention times, retention factors or peak profiles. This approach can be used to provide information on the strength of binding by a target with an affinity ligand and on the competition of the target with other compounds for the binding agent [1–3,11,31,51,57,108,109]. In this type of experiment, a narrow plug of the target is injected onto the affinity column under isocratic conditions as a detector is used to monitor the elution time or profile for the injected analyte. If relatively fast association and dissociation kinetics are present on the time scale of the experiment, the retention time of the target should be directly related to the target’s strength of binding to the immobilized agent and the amount of active binding agent that is present in the column [2,11,30,31,109]. Factors that can be altered during zonal elution experiments include the mobile phase pH, ionic strength and polarity, as well as the temperature, type of target, type of affinity ligand in the column, and the presence of competing or displacing agents in the mobile phase. By monitoring the changes in the retention for the target as these conditions are varied, detailed data can be obtained on the nature of the interactions between the target and the immobilized binding agent [2,11,31,66,70,109–111].

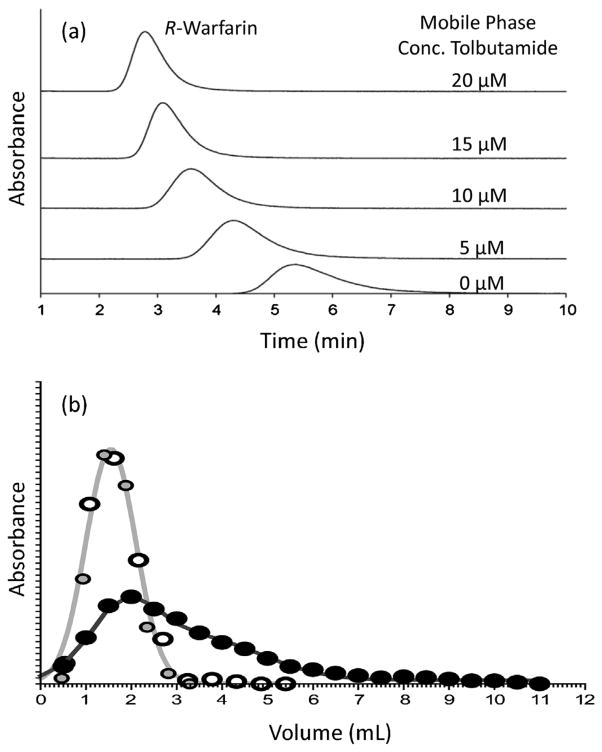

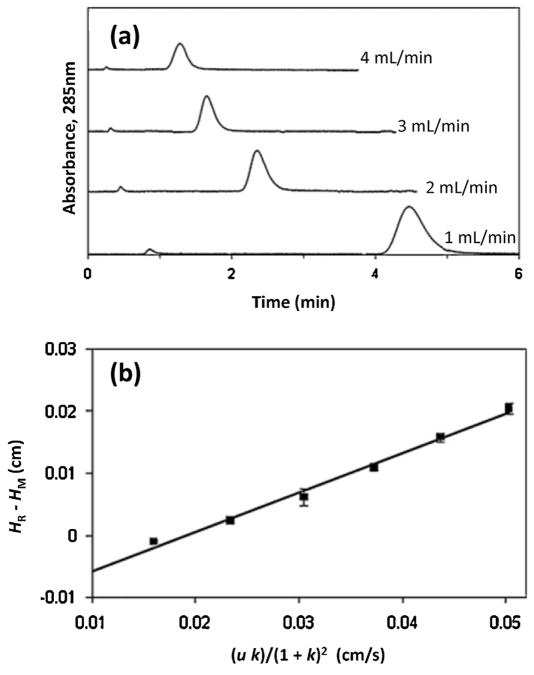

Fig. 3(a) shows a typical zonal elution experiment in which competition by a mobile phase additive causes a shift in the retention of an injected target as these two compounds compete for binding sites on an immobilized affinity ligand [110]. This example shows the chromatograms generated during injections of the site-selective probe R-warfarin onto a 2 cm × 2.1 mm i.d. column (volume, 69 μL) that contained the immobilized protein human serum albumin (HSA), with the drug tolbutamide being placed into the mobile phase as a competing agent. In this specific experiment, a decrease was observed in the retention of R-warfarin as the concentration of tolbutamide was increased, indicating that either direct competition or a negative allosteric effect was occurring between these two compounds on HSA [110].

Fig. 3.

Examples of the use of zonal elution with affinity microcolumns in examining biomolecular interactions. In (a) competition studies based on zonal elution were carried out using the injection of R-warfarin as a site-specific probe onto a microcolumn containing immobilized human serum albumin (HSA) in the presence of various concentrations of tolbutamide in the mobile phase. The results in (b) show the elution profiles for retinoic acid receptor γ (RARγ) that was applied to columns containing apo-cellular retinoic acid binding protein II (CRABP II) (open circles) or holo-CRABP II (black circles) and in the presence of retinoic acid; the gray-shaded circles represent an elution profile of carbonic anhydrase II (CA II) applied to an apo-CRABP II column. Adapted with permission from Refs. [110,112].

Another format in which zonal elution has been employed with microcolumns is shown in Fig. 3(b). In this case, the immobilized binding agent is used to examine the binding of a retained target with a second binding agent that is applied in the mobile phase [112]. The column in this particular example was 275 μL in volume and contained an immobilized form of cellular retinoic acid binding protein (CRABP) that was initially loaded with the target retinoic acid. A sample of a second possible binding agent for retinoic acid (i.e., retinoic acid receptor isoform γ, or RARγ) was then applied to the column and examined for its elution profile. The presence of a shift in the elution profile for this applied binding agent versus a control was used to detect an interaction between RARγ and CRABP during the transfer of retinoic acid between these binding agents [112].

One advantage of zonal elution is it requires only a small amount of target for injection. This method can also examine more than one compound in a sample provided there is adequate resolution between the peaks for these compounds or a detection format is employed that can distinguish between these eluting solutes [57]. As is illustrated in Fig. 3(a and b), it is also possible with zonal elution to obtain information on site-specific interactions, on the competition of two targets for the same binding agent [109,113,114] or on the competition of two binding agents to the same target [115]. As will be demonstrated in the next few sections, this format can also provide information on the strength of binding and the effects that changes in the structure of a target or binding agent may have on an interaction.

2.2. Estimating binding strength and retention using affinity microcolumns

Zonal elution can be used in a variety of ways to obtain information on biomolecular interactions. An important parameter to measure when describing these interactions is the degree or strength of binding that occurs in the system [11,57,116–126]. This information can be obtained from the retention time or retention factor (k) for a target that is injected onto an affinity column. This retention factor can be calculated from the observed elution times through the following relationship,

| (1) |

where tR is the observed retention time for the injected target, and tM is the column void time.

If relatively fast association/dissociation kinetics and linear elution conditions are present during the measurement of the retention factor (i.e., the apparent value of k is not affected by the amount of injected sample or the flow rate), Eq. (2) can be used to relate this retention factor to the number of binding sites for the target in the affinity column and to the association equilibrium constants for the target at these sites [11,31].

| (2) |

In this equation, the terms Ka1 through Kan represent the association equilibrium constants for the target at each of its binding sites in the column, n1 through nn are the fractions for each type of site in the column, mL is the total moles of all binding sites in the column, and VM is the void volume of the column.

The global association equilibrium constant (nKa) for the interaction of a target with the immobilized binding agent can be obtained from the numerator of Eq. (2), where nKa is the summation of the terms Ka1n1 through Kannn. This term is directly proportional to k if all of the binding sites have independent interactions with the target. If the target binds to only one type of site on the affinity ligand and in the column, the multisite equation in Eq. (2) can be rearranged to the simpler form that is provided in Eq. (3),

| (3) |

where Ka is the association equilibrium constant for the interaction, mL/VM represents the molar concentration of the binding sites for this interaction, and other terms are as defined previously [11,31].

A few recent studies have examined the ability of short affinity microcolumns to be used with zonal elution for estimates of retention factors and binding strength. One set of experiments was carried out at various flow rates for the drugs carbamazepine and warfarin when applied to HSA affinity microcolumns [116]. These columns contained 4.6 mm i.d. silica monoliths with lengths of 1–5 mm or were 4.6 mm i.d. columns that were 3 mm in length and that contained HSA immobilized to silica particles. It was found that similar retention factors were obtained for warfarin on 3–5 mm long microcolumns, and for carbamazepine when the column length ranged from 1 to 5 mm. These results indicated micro-columns as short as 1–3 mm could be used to provide reproducible retention factors for drug–protein binding studies that involve systems with binding constants in the range of 103–106 M−1 [116]. Additional work was carried out with racemic warfarin and L-tryptophan on 2.1 mm i.d. HSA microcolumns that contained silica particles and that ranged in length from 1 mm to 2 cm. This report also indicated that columns as small as only a few millimeters in length could be used for zonal elution studies of drug–protein binding for systems with affinities of 104–106 M−1 [103]. Some loss of precision in retention measurements did occur with the use of these small columns and there was a greater chance of column overloading [103,116]. However, it was noted that the latter effect could be dealt with by decreasing the sample load or by using reference compounds and retention ratios to adjust for shifts in the retention factors [103].

The fact that the retention factor is related both to the association equilibrium constants and number of binding sites for an interaction can be used in a variety of ways. For instance, retention factor measurements of R- and S-propranolol, as model drugs, have been used in examining the long-term stability of affinity microcolumns that contained high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) [117–119]. If an independent estimate is available for the binding capacity (mL), it is possible to use this information with measured retention factors and Eqs. (2) or (3) to estimate the value of nKa for a multi-site system, or Ka for a single-site interaction. This method has been used to screen and compare the binding of several site-selective probes and sulfonylurea drugs on microcolumns containing entrapped samples of HSA or glycated HSA [120]. Zonal elution data (with detection based on mass spectrometry) has been combined with binding capacities obtained by frontal analysis on a packed capillary containing cyclin G-associated kinase for drug discovery; the results were then used to estimate and rank the affinity of the kinase for a series of drug fragments [123]. A similar method was used to rank the binding constants for various drug fragments with the chaperone protein HSP90 (see Fig. 4) [50] and for various carbohydrates in their binding to hen egg-white lysozyme [54]. It is also possible to use the ratio of the retention factor to the known amount of binding agent to provide an index that is related to nKa or Ka [126]. This technique has been used to compare the activities and properties for proteins attached within organic-based monoliths that were prepared under various polymerization conditions [100].

Fig. 4.

Use of zonal elution and mass spectrometry with a 0.5 mm i.d. × 10 cm packed capillary containing the N-terminal domain of the protein HSP90 to compare the relative retention of four drug fragments (four upper chromatograms in each plot), using adenosine (bottom chromatogram in each plot) as a reference. Adapted with permission from Ref. [50].

2.3. Competition and displacement studies using affinity microcolumns

Zonal elution and traditional HPAC or affinity columns have often been employed in studying the competition and displacement between drugs and other solutes during solute-protein interactions [11,31,45,57,84]. In this type of experiment, a competing agent is placed at a fixed concentration in the mobile phase. A small pulse of a target or site-selective probe is then injected onto the column and allowed to interact with the immobilized binding agent, as illustrated earlier in Fig. 3(a). As the target passes through the column, the competing agent may influence binding by the target to the affinity ligand through direct competition or allosteric effects. When these data are fit to the response that is predicted by various models, the types of interactions that are occurring between the target, competing agent and immobilized binding agent can be determined. This, in turn, can provide information on the number of interaction sites, the location of these sites (i.e., through the use of site-selective probes), and the binding strength at particular sites [31,127–133].

To illustrate this process, Eq. (4) shows the response that would be expected between the retention factor for an injected solute and the concentration of a competing agent in the mobile phase if these two solutes have direct competition at a single type of site on an affinity column [11,31,57].

| (4) |

In this equation, Ka,AL and Ka,IL are the association equilibrium constants for the interactions of the immobilized binding agent (or affinity ligand, L) with the target/analyte (A) and the competing agent (I) at their site of competition. This relationship predicts that a linear response with a positive slope should be obtained for a plot of 1/k versus [I] if A and I have a single site of competition. This relationship, in turn, can be used to provide the value of Ka,IL for I at its site of competition with A. If no competition is present between A and I, this type of plot will show only random variations in 1/k as [I] is increased. If negative allosteric effects or multisite interactions are present, deviations from a linear response at low concentrations of I should be obtained. If positive allosteric effects are present, the value of 1/k should decrease as the concentration of I is increased [31,57].

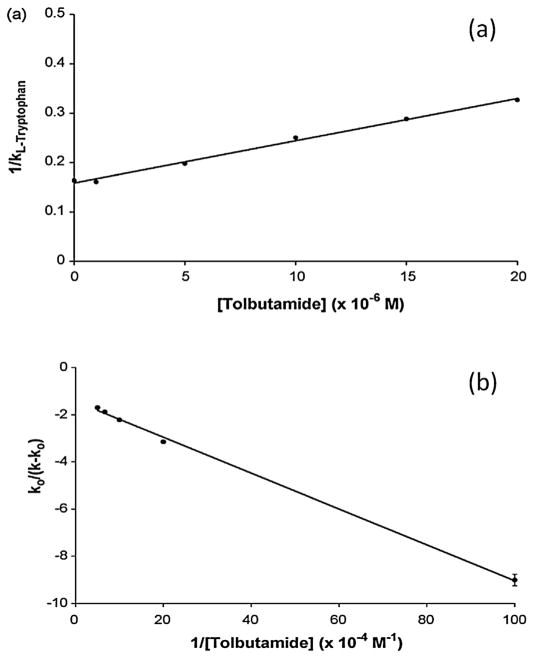

Plots made according to Eq. (4) have been used in many recent studies involving affinity microcolumns. An example of a plot from a study that used a microcolumn containing HSA is shown in Fig. 5(a) [110]. In this case, a linear response was obtained in a plot of 1/k for L-tryptophan as the concentration of tolbutamide was varied in the mobile phase. This result indicated that tolbutamide had direct competition with L-tryptophan at Sudlow site II, the known binding site for the latter compound with HSA. The same approach has been employed with affinity microcolumns to investigate the competition of various probes with a number of other drugs during their interactions with the proteins HSA, glycated HSA, and α1-acid glycoprotein (AGP) [44,45,109,110,113,130–133]. Alternative forms of Eqs. (3) and (4) have been used with other systems [51,53,84,134]. One example was the use of competitive zonal elution studies to examine the binding of L-fucose, as a mobile phase additive, to immobilized Aleuria aurantia lectin as injections of the oligosaccharide LNF III were made as a probe [51].

Fig. 5.

Results of zonal elution competition studies on HSA microcolumns examining the change in retention of (a) L-tryptophan as a probe for Sudlow site II and (b) R-warfarin as a probe for Sudlow site I in the presence of tolbutamide as a competing agent. The solid lines show the best-fit responses that were obtained when fitting (a) Eq. (4) or (b) Eq. (5) to the data. These results were obtained under similar or identical conditions to those used in Fig. 3(a). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [110].

Another type of graph that can be used to analyze both direct competition and allosteric effects using zonal elution data is given in Fig. 5(b). In this case, a plot of k0/(k − k0) versus 1/[I] is made according to Eq. (5), where k0 and k are the retention factors for injected target A in the absence and presence of the competing agent, respectively [135].

| (5) |

This equation is based on a model where A and I may have direct competition at a single site or allosteric interactions through two different sites. If an allosteric effect is present, the ability of A to bind to L is influenced by the binding of I on L, which causes the association equilibrium constant for A to change from Ka,AL to . This change can also be described by the coupling constant βI→A, which is equal to the ratio . A linear relationship obtained from this plot can be used to determine the association equilibrium constant for I with L (Ka,IL) and the coupling constant, βI→A. A value of βI→A between 0 and 1 indicates that a negative allosteric effect is present between A and I, while a positive allosteric effect is indicated if βI→A is larger than 1. A unique advantage of this method is that it can be used to look independently at both directions of an allosteric effect by changing which compound is used as A or I in the experiment [135–137].

Plots made according to Eq. (5) have been used in various studies of biomolecular interactions based on affinity microcolumns. Fig. 5(b) is one example, which was used to determine how binding by R-warfarin to HSA was affected by tolbutamide as a competing agent. This plot was used to help differentiate between allosteric effects and multi-site binding during the interaction of these two solutes on an HSA microcolumn [110]. Eq. (5) and similar plots have been utilized with microcolumns to study the interactions between various fatty acids and sulfonylureas with HSA or glycated HSA [138] and allosteric effects that may occur on AGP as it binds to S-propranolol and warfarin [113].

Experiments based on competition studies and zonal elution can further be used to determine the location and structure of binding regions on proteins or other biomolecules. This is done by using an injected probe compound that is known to bind to a specific site on the protein or affinity ligand, with the competing agent in the mobile phase being the compound for which possible interactions at this site are being examined [31]. Such an experiment is illustrated by the examples provided in Fig. 5. With this technique it is possible to develop a model of both the number of binding regions a solute may have with a protein, or other type of affinity ligand, and the association equilibrium constants for the solute at each of these sites. This technique has been used with microcolumns containing HSA or modified forms of this protein to study the interactions of drugs such as acetohexamide, tolbutamide, gliclazide, gliben-clamide and imipramine at Sudlow sites I and II or the digitoxin site of this protein [44,45,110,130–133,139]. The same method has been employed to look for common binding regions of drugs and drug enantiomers on microcolumns that contained AGP [113].

2.4. Other applications of zonal elution with affinity microcolumns

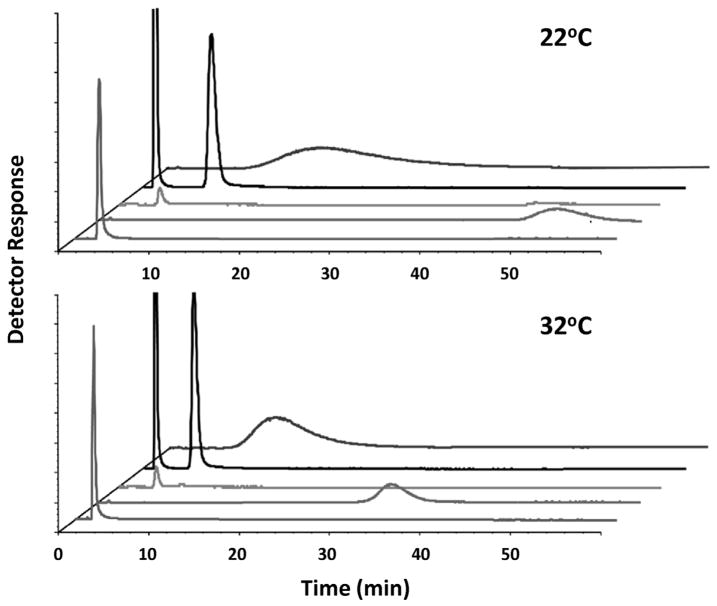

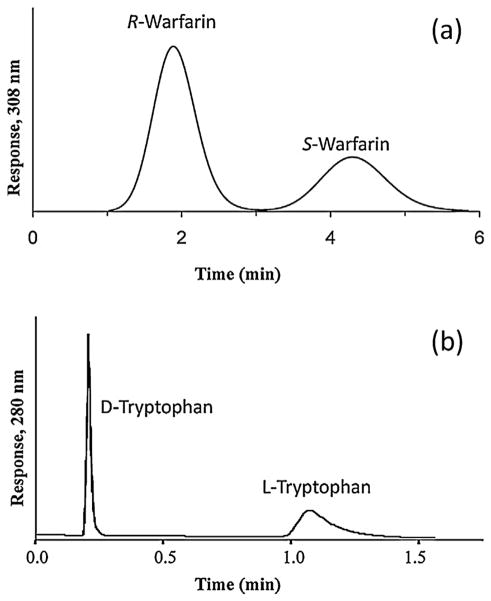

Another application of zonal elution is its use in examining the effects of various conditions on binding of the target with the affinity ligand. Conditions that can be altered during such studies include the temperature, pH, ionic strength and content of the mobile phase [31,66,70,111,140–142]. For instance, varying the polarity of the mobile phase can be used to alter non-polar interactions between a target and a protein, and/or change the conformation of the protein or the target. This is a common tactic used with chiral stationary phases based on proteins to alter their retention and stereoselectivity [40,140,141,143]. Some examples are provided in Fig. 6, in which an organic modifier was used to increase the speed of chiral separations for R/S-warfarin and D/L-tryptophan on a 4.6 mm i.d. × 10 mm microcolumn that contained HSA immobilized to an organic monolith [100].

Fig. 6.

Chiral separations for (a) R- and S-warfarin and (b) D- and L-tryptophan on a 4.6 mm i.d. × 10 mm microcolumn containing HSA immobilized to a monolith based on a co-polymer of glycidyl methacrylate and ethylene glycol dimethacrylate. The mobile phase was pH 7.4, 0.067 M phosphate buffer that contained 0.5% 1-propanol and the flow rate was (a) 2.0 mL/min or (b) 3.0 mL/min. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [100].

It is also possible to use zonal elution to examine the effects of changes in the structure of a target on its interactions with a given binding agent. This general approach can involve creating a quantitative structure–retention relationship (QSRR), in which the retention factors for a set of structurally related molecules are measured on an affinity column under otherwise similar temperature and mobile phase conditions. These data are then compared to various factors that describe the structural components of the applied targets to see which of these factors most affected the retention [35,144–147]. This technique has been used with traditional HPAC columns to investigate the skin permeation of several organic molecules through the use of a column containing immobilized keratin [144], to characterize binding of HSA to benzodiazepine drugs [145–147], and to examine the interactions of AGP with antihistamines, beta-adrenolytic drugs, and other agents [148–154]. In work with affinity microcolumns, the same general method has been used to compare the binding of various sulfonylurea drugs at both Sudlow sites I and II of HSA [155].

A related approach is to use affinity microcolumns to see how biomolecular interactions change as variations are made in the structure of the immobilized binding agent [156–158]. This tactic has been used to see how the non-enzymatic glycation of HSA, as occurs during diabetes [129,159], may alter the binding of this protein to various drugs and solutes. These studies have used R-warfarin, L-tryptophan and digitoxin as probes (i.e., for Sudlow sites I and II and the digitoxin site of HSA, respectively), along with samples of glycated HSA that had various known levels of modification. The results for in vitro glycated samples indicated that changes in the affinities for sulfonylurea drugs and L-tryptophan did occur as the level of glycation for HSA was increased and that these changes differed between solutes and the binding site that was examined [45,110,130–133]. Similar effects were seen in affinity microcolumns that contained in vivo glycated HSA that was obtained from several patients with diabetes [44].

Affinity microcolumns and zonal elution have also been used in the high-throughput screening of compound fragment mixtures based on WAC and mass spectrometry (WAC-MS). This method has been utilized to screen the binding of drugs to albumin [32] and binding of compound fragments to protease [52,160] or kinase targets [123]. As an example, one recent study showed that 111 fragments could be screened on a capillary column containing the protein HSP90, as illustrated earlier in Fig. 4. The results of WAC were found to show good agreement with data obtained by NMR, SPR, and isothermal titration calorimetry, as well as crystallographic data [50].

3. Frontal analysis and affinity microcolumns

3.1. Principles of frontal analysis

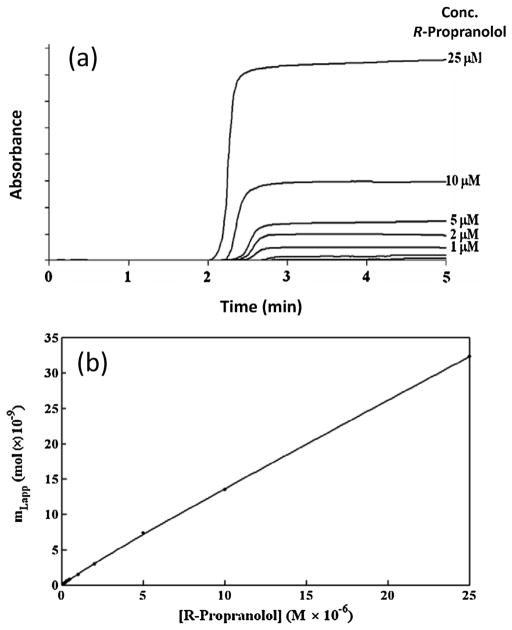

Frontal analysis, or frontal affinity chromatography (FAC), is another common technique that is used in HPAC and affinity chromatography to study biomolecular interactions. In this method, a target solution is continuously applied to a column while the amount of target that elutes from the end of the column is monitored [57,109,161]. As the target binds to the immobilized affinity ligand, the column begins to become saturated and the amount of the target that elutes from the column increases with time or with the volume of applied target [31]. The result is the formation of a breakthrough curve, as is illustrated in Fig. 7(a) for R-propranolol that was applied to an affinity microcolumn containing HDL as the binding agent [117].

Fig. 7.

(a) Typical chromatograms (i.e., breakthrough curves) obtained for a frontal analysis experiment, as obtained here for the application of various solutions R-propranolol to a 5 cm × 2.1 mm i.d. column containing immobilized high-density lipoprotein (HDL). (b) Analysis of frontal analysis data obtained for R-propranolol on the HDL column by fitting to the results to a model based on a combination of a saturable binding site and a non-saturable interaction. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [117].

Frontal analysis was first used with traditional affinity columns in the mid-to-late 1970s [162–164]. In the early 1990s this technique was used with HPAC to study drug–protein binding [165]. Over the last 10–15 years, this method has been utilized with various types of affinity microcolumns and capillary columns for binding studies; this includes the combination of this method with mass spectrometry, giving a method known as frontal affinity chromatography–mass spectrometry (or FAC-MS) [46,90–92,117,166].

There are several advantages, and potential disadvantages, to using frontal analysis versus zonal elution to examine a biomolecular interaction. For instance, frontal analysis is easier to use in providing independent information on both the overall number of binding sites for an interaction and the equilibrium constants for these interactions [11,31]. On the other hand, zonal elution competition experiments, as discussed in the previous section, are more convenient for identifying interaction sites and measuring binding constants specifically at these sites. Frontal analysis tends to require more solute than zonal elution, but column overloading effects are not a problem in frontal analysis because column saturation is actually a desirable feature for at least part of such an experiment [31]. In addition, the higher amounts of a target that are typically used in frontal analysis can make it easier to detect an interaction with this method than when using zonal elution [31,46,90].

3.2. Estimating binding strength and number of sites using affinity microcolumns

An important application of frontal analysis is the use of this approach to obtain information on both the overall number of interaction sites an applied target has with an immobilized affinity ligand and the equilibrium constants for these interactions. Data can be obtained for this purpose by applying to the affinity column a wide range of target concentrations, as demonstrated earlier in Fig. 7(a). The mean position of the breakthrough curve is then measured at each applied concentration of the target, and the resulting data are fit to various binding models, as illustrated in Fig. 7(b) [117]. For instance, either Eq. (6) or (7) can be used to describe a system in which a single-site interaction is occurring between the target and the immobilized binding agent [31].

| (6) |

| (7) |

In these equations, mL,app is the apparent moles of target that is required to reach the mean position of the breakthrough curve at a given concentration of the applied target or analyte ([A]). The term Ka is the association equilibrium constant for this process, and mL is the total moles of active binding sites that are involved in this interaction. By using a non-linear fit of mL,app versus [A] to Eq. (6), or a linear fit of 1/mL,app versus 1/[A] to Eq. (7), the values of both Ka and mL can be obtained for this system. If multiple types of binding sites or interactions are present, alternative binding models and equations can also be fit to the data [31,167,168].

An example of this type of analysis when using an affinity micro-column is provided in Fig. 7(b). This example shows the use of a model based on both a saturable binding site and a non-saturable interaction to describe the interactions of R-propranolol with HDL [117]. This approach has been employed with small columns in HPAC and with other drugs and serum agents, such as the binding of S-propranolol and verapamil with HDL [117], the interactions of R- and S-propranolol with LDL [118], the binding of drugs with AGP [113,169–173], and the interactions of various drugs and solutes with HSA or modified HSA [44,45,108,110,130–133,139]. Frontal analysis was used to determine the binding capacity of adenosine on a packed capillary containing cyclin G-associated kinase [123], and FAC-MS has been used with open-tubular capillaries containing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors to compare and rank the binding of the agents to various urediofibrate-like dual agonists [36]. Capillary monolith columns containing lectins or enzymes have been employed with FAC-MS to examine the equilibrium constants of applied targets with these affinity ligands [41,46,48]. FAC-MS has also been coupled with capillary columns for the high throughput screening of enzyme inhibitors, oligosaccharides, and other targets for immobilized binding agents [166].

The effect of column size on the results of frontal analysis experiments has been recently examined for systems with low-to-moderate affinity interactions [103]. This work used HSA as the immobilized binding agent and warfarin as a model target (i.e., a drug with single-site binding to HSA and a well-characterized affinity for this site). Table 1 shows the results that were obtained for 2.1 mm i.d. microcolumns with lengths ranging from 2 cm down to only 1 mm and packed with silica particles. Each of these columns gave a good fit for their frontal analysis data to a single-site model, and the measured binding capacity decreased in proportion to the total column volume. It was also found that all of these columns gave association equilibrium values that were in good agreement with literature values; however, the results obtained for the short columns did have less precision that those obtained for the longer columns. The main benefit of using the shorter columns was the much smaller amount of immobilized binding agent that they required and their shorter residence times. These features made these affinity microcolumns appealing for future use in the high-throughput screening of drug candidates and in rapid studies of drug-protein binding [103].

Table 1.

Effect of column length on the association equilibrium constants (Ka ) and binding capacities (mL ) measured by frontal analysis for warfarin on affinity microcolumns containing immobilized human serum albumina.

| Column length (mm) | Column volume (μL) | mL (nmol) | Ka (×105 M−1) | Relative activityb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 69 | 27.6 (±0.2) | 2.0 (±0.1) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 10 | 35 | 9.7 (±0.2) | 3.0 (±0.1) | 0.68 (±0.02) |

| 5 | 17 | 4.1 (±0.3) | 3.4 (±0.3) | 0.58 (±0.05) |

| 3 | 10 | 3.8 (±0.3) | 2.3 (±0.1) | 0.92 (±0.08) |

| 2 | 6.9 | 2.6 (±0.3) | 2.1 (±0.2) | 0.92 (±0.08) |

| 1 | 3.5 | 1.2 (±0.1) | 2.6 (±0.8) | 0.83 (±0.08) |

The inner diameter of all the columns was 2.1 mm. The Ka and mL values provided are the average results obtained over flow rates ranging from 0.5 or 1.0 to 2.0 mL/min. The results in this table are based on data provided in Ref. [103].

The relative activities were determined by comparing the specific activity measured for each column to the specific activity measured for the 2 cm long column.

3.3. Competition and displacement studies using affinity microcolumns

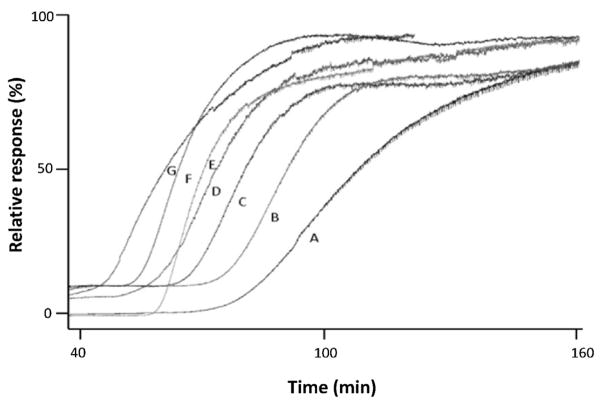

Frontal analysis, and especially FAC-MS, has also been used to examine the competition between potential targets and immobilized binding agents on affinity microcolumns [36,37,57]. In this type of study, a competing agent is added with the target in the mobile phase. The resulting chromatograms are then analyzed by measuring the change in breakthrough time or volume of the target as a function of the competing agent’s concentration (see Fig. 8) [37]. Direct competition or negative allosteric effects between the target and competing agent can be detected when the breakthrough time decreases with an increase in the competing agent’s concentration. Alternatively, positive allosteric effects can lead to a larger breakthrough time for the target as the concentration of the competing agent is increased [57].

Fig. 8.

Example of a displacement experiment using frontal analysis and detection based on mass spectrometry. These chromatograms show the effects of adding (B) vitexin, (C) naringenin, (D) apigenin, (E) quercetin, (F) kaempferol, or (G) luteolin to a solution containing (A) quercetin as the target and applied to a 30 cm × 100 μm i.d. open-tubular capillary column containing an immobilized form of the histone decarboxylase SIRT6. Adapted with permission from Ref. [37].

It is possible to obtain a qualitative ranking of the strength of displacing agents based on chromatograms like those in Fig. 8, but a quantitative analysis of such data is possible as well. For instance, Eq. (8) has been used to describe the interactions between a competing agent (I) and the target during such an experiment [36,37,174–176].

| (8) |

In this expression, Kd,IL is the dissociation equilibrium constant of the competing agent with the immobilized affinity ligand, [I] is the concentration of the competing agent, VR is the breakthrough volume of the target, and Vmin is the breakthrough volume of the target when the interaction being examined is completely suppressed (i.e., as can be determined by running the target with a high concentration of the competing agent). The term P is the product of the number of active binding sites and the term Kd,IL/Kd,AL, where Kd,AL is the dissociation equilibrium constant for the target (or analyte) with the immobilized ligand.

Several reports have used Eq. (8) or equivalent relationships in displacement studies based on FAC-MS and affinity microcolumns [36,37]. The example in Fig. 8 utilized an open-tubular capillary that contained the histone deacetylase SIRT6. This column was used with FAC-MS to estimate the dissociation equilibrium constants for several structurally related flavonoids based on their ability to displace quercetin, a known inhibitor for SIRT6 [37]. Open-tubular capillaries containing the ligand binding domains of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors were employed in a similar manner to examine the interactions and rank the affinities of ureidofibrate-like dual agonists with these columns [36].

3.4. Other applications of frontal analysis with affinity microcolumns

As mentioned earlier, changes in factors such as the temperature or mobile phase can alter a biomolecular interaction. Like zonal elution, frontal analysis can be employed to see how such changes may alter an interaction. One advantage of using frontal analysis for this purpose is it can be used to independently examine how both the affinity and moles of binding sites are affected by a change in the temperature or reaction conditions [31,143]. As an example, the effect of temperature on the binding for Rand S-propranolol with HDL and LDL has been studied using affinity microcolumns [117–119]. The results showed that a change in temperature had little effect on either the association equilibrium constants or the binding capacities between these drugs and binding agents [117–119].

Frontal analysis has also been used to examine the binding of solutes to modified proteins. This technique has been utilized to compare the binding of several solutes to HSA that has been modified to various extents by glycation [44,45,130–133]. Both the affinities and binding capacities for targets such as warfarin, L-tryptophan and sulfonylurea drugs were considered in going from normal HSA to in vitro [45,130–133] or in vivo [44] samples of glycated HSA. Warfarin and L-tryptophan were found to bind to both sets of proteins through a single-site interaction [122,131], but the sulfonylurea drugs interacted through a two-site model that involved a set of high and low affinity sites [130]. The results indicated that the glycation of HSA could affect the affinity of this protein for L-tryptophan and some of the sulfonylurea drugs, but no appreciable change was noted for warfarin under modification conditions similar to those seen in diabetes [44,131].

Affinity microcolumns and frontal analysis have been used in a growing number of reports for the high-throughput screening of compound mixtures with regards to their binding to biological ligands. This research has used FAC-MS to rank and measure the binding of several applied compounds in a single experiment, as demonstrated with columns that have contained enzymes, antibodies, lectins or human estrogen receptor β [166]. FAC-MS and such columns have been employed to screen the binding of enzyme inhibitors, oligosaccharides and peptide libraries [49,166,175,176]. For instance, an open-tubular capillary containing an immobilized nuclear receptor was used in FAC-MS to determine the relative affinities for a series of chiral fibrates with this receptor [35].

4. Other methods for studying biomolecular interactions using affinity microcolumns

4.1. Peak decay analysis

Peak decay analysis is a method for kinetic analysis that is particularly well-suited for use with affinity microcolumns [177–180]. This method was first described in 1987 [177] and was originally based on the application of a target to an immobilized binding agent, followed by the application of a high concentration of a competing agent to displace the retained analyte. This early work used a column containing the lectin concanavalin A to determine the dissociation rate constant for the sugar 4-methylumbelliferyl α-D-mannopyranoside from this binding agent, with 4-methylumbelliferyl α-D-galactopyranoside acting as a competing agent to avoid rebinding by the target sugar during the elution process [177]. It was shown in later work with weak-to-moderate affinity systems that a modified version of this method can be used in which no competing agent is required [178–180].

In a typical peak decay experiment, the elution step is carried out at a flow rate, column size and/or competing agent concentration that prevents the displaced analyte from rebinding to the column [31,177–180]. The flow rate, support material and column size also need to be selected to provide mass transfer between the flowing and stagnant regions of the mobile phase that is faster than the rate of dissociation for the target from the immobilized binding agent. If these conditions are met, the resulting elution profile can be used to obtain the dissociation rate constant for the target from the binding agent [31,177].

Once the elution profile has been collected for the target, a plot can be made of the logarithm of the peak response versus time. If dissociation of the target from the immobilized binding agent is the rate-limiting step for elution and no rebinding of the target occurs to the column, Eq. (9) can be used to determine the dissociation rate constant for the target from the immobilized binding agent [31,177].

| (9) |

In this equation, the mEo is the initial moles of target that were bound to the column, mEe is the moles of the target that elute in the mobile phase at time t, and kd is the dissociation rate constant of the target from the immobilized binding agent. Under the given conditions, Eq. (9) predicts that there should be a linear relationship between the natural logarithm of the elution peak, ln(dmEe/dt), and the time allowed for target elution, t. The dissociation rate constant can then be obtained from the slope of the resulting curve [2,31,177].

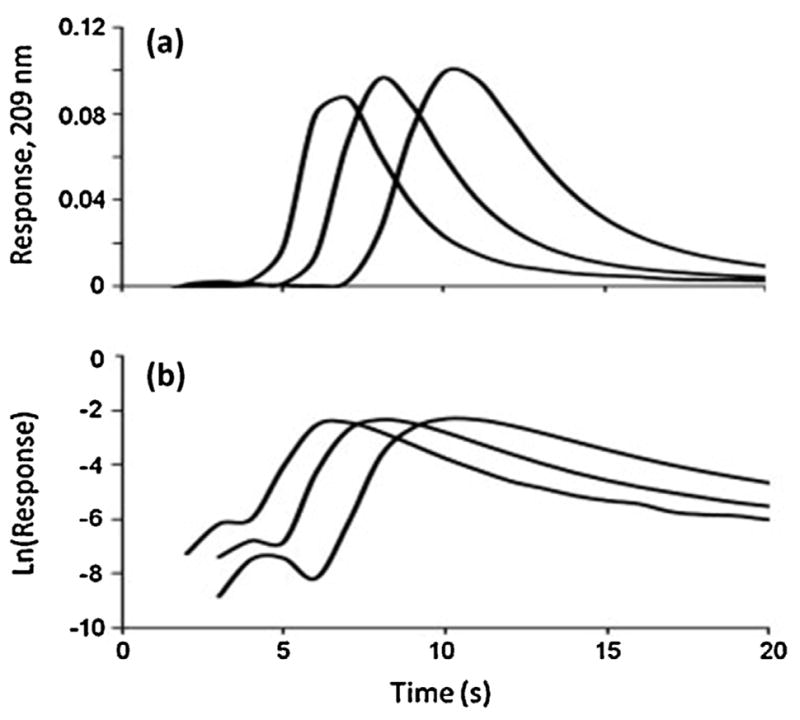

An example of peak decay experiment is shown in Fig. 9, in which the dissociation of nortriptyline is examined by using the peak decay method with an AGP microcolumn containing silica particles [180]. This particular example is based on a non-competitive peak decay method, in which short microcolumns and high flow rates, rather than a competing agent, are used to reduce the possibility of a target rebinding to the column. This method has recently been modified for use with affinity microcolumns containing silica monoliths to study the dissociation rates for a large set of drugs (i.e., warfarin, diazepam, imipramine, acetohexamide, tolbutamide, amitriptyline, carboplatin, cisplatin, chloramphenicol, nortriptyline, quinidine and verapamil) with HSA [173,180]. This approach has also been applied with affinity microcolumns that contain AGP to estimate the dissociation rate constants of this protein for amitriptyline and lidocaine, as well as nortriptyline [180].

Fig. 9.

Typical results for a peak decay experiment, as obtained for the injection of nortriptyline at flow rates of 5, 7 or 9 mL/min (from right-to-left) on a 1 mm × 4.6 mm i.d. microcolumn containing immobilized AGP. This example includes the (a) elution profiles and (b) natural logarithm of these elution profiles for a 100 μL injection of 20 μM nortriptyline. Reproduced with permission Ref. [180].

Another variation of the peak decay method occurs when a change in a factor such as pH is used to cause release of the target and to prevent rebinding of this target to the column. For example, this method was used to determine the dissociation rate constants of the herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), and related solutes, from immobilized antibodies at various pH values and flow rates. This information was then used to help in the design and optimization of an HPAC system for the analysis of 2,4-D and related herbicides in water samples [179]. The peak decay method has also been utilized to study the elution kinetics of thyroxine from columns containing immobilized antibodies or aptamers [181] and to examine the dissociation of immunoglobulin G-class antibodies from protein G (i.e., an antibody-binding protein) [113].

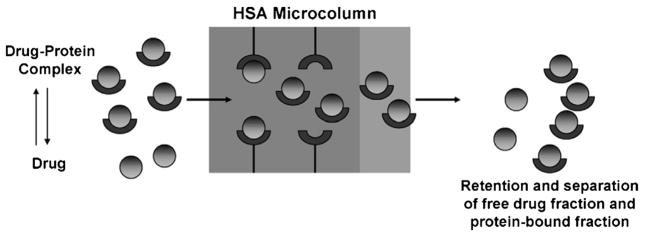

4.2. Ultrafast affinity extraction

Another method for examining biomolecular interactions and using microcolumns is ultrafast affinity extraction [38,39,80,101,102,104,182]. This approach examines the interaction of a target and a binding agent that is in solution but uses an affinity microcolumn to probe the non-bound, or free, fraction of the target that remains. In this technique, the target is injected in the presence or absence of the soluble binding agent onto a microcolumn that contains an affinity ligand that can selectively retain the target in its free form. This affinity ligand may be a specific agent, such as an antibody for a given target [80,101,182]. Alternatively, the affinity ligand may be a more general binding agent, such as a serum transport protein like HSA for the retention of various drugs [38,39,102,104]. If the flow rate and column conditions are selected correctly, the residence time for the sample in the column can be made small enough that no significant dissociation will occur of the target from the soluble binding agent as the sample passes through the column. For instance, affinity microcolumns have been used to produce sample residence times down to the low-to-mid millisecond range for this method [38,40,104].

This type of study is carried out by using the general scheme shown in Fig. 10, in which an affinity microcolumn containing HSA is used to separate the free and protein-bound fractions of a drug or small target in a sample [38]. In this example, the protein-bound fraction of the target and the protein in the sample will elute first in the non-retained fraction. This is followed later by elution of the retained free fraction of the target. The free fraction of the target can then be determined by comparing the measuring retained peaks for the target in the presence or absence of the soluble binding agent. This information, in turn, can be used to determine the association equilibrium constant for the interaction of the target with the binding agent in the sample if the binding agent’s total concentration is also known. For instance, Eqs. (10) and (11) describe the relationship between the observed free fraction (f) and the association equilibrium constant (Ka) for a target (A) and soluble binding agent (P) that have a single-site interaction.

Fig. 10.

General scheme for the use of ultrafast affinity extraction with an HSA microcolumn to separate the free and protein-bound fractions of a drug or solute in an injected sample. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [38].

| (10) |

| (11) |

In these equations, CA is the total concentration of the target in the original sample, CP is the total concentration of soluble binding agent, and [A-P] is the concentration of the target-binding agent complex in the original sample [38,40].

One advantage of free fraction analysis is its ability for rapid measurements. This is partly due to the fact that sample residence times in the range of only a few hundred milliseconds or less are used to minimize the possibility that the target may dissociate from the soluble binding agent during the analysis [38,40,104]. It has been shown that the results obtained by this technique are comparable to those found with the reference methods such as ultrafiltration and equilibrium dialysis, among others [38–40,57,182]. Furthermore, because this method directly examines the interactions between a target and a soluble binding agent, it is not subject to the immobilization effects that can occur with other affinity methods if improper conditions are used to couple the binding agent to the support [38,39,80,101,102,104,182].

Several recent studies have used ultrafast affinity extraction to examine biomolecular interactions. For instance, this method has been used with immobilized antibodies and fluorescence detection to measure the free drug fraction in mixtures of warfarin and HSA [104]. This technique has also been combined with a displacement immunoassay to measure the free fraction of thyroxine and phenytoin in clinical samples by using chemiluminescence or near-infrared fluorescence detection [39,102,182]. Use of this scheme to estimate association equilibrium constants has been shown with HSA and drugs such as R- or S-warfarin, S-ibuprofen and imipramine to give good agreement with the values obtained by other methods [38]. In a recent study, a multi-dimensional HPAC system was developed by combining ultrafast affinity extraction with a chiral stationary phase to simultaneously examine the free fraction of warfarin enantiomers in serum or drug–protein mixtures. The binding constants that were estimated for R- and S-warfarin with HSA or serum by this approach also gave results comparable to those of a reference method and literature values [40].

4.3. Split-peak analysis

The split-peak method is another technique that is readily employed with affinity microcolumns. This is a method of kinetic analysis that is based on the fact that there is a probability during a chromatographic separation that a small fraction of target will elute non-retained from the column without interacting with the stationary phase. In HPAC, this method can be used to study the rate of association of a target with an immobilized binding agent by using column size and flow rate conditions that promote the probability of this effect [97].

The following equation describes how the relative size of the non-retained target fraction (f) will change with the flow rate when a small amount of target is injected onto such a column [97].

| (12) |

In Eq. (12), F is the flow rate, mL is the moles of active and immobilized binding agent in the column, and Ve is the excluded volume (i.e., the volume of flow mobile phase) in the column. The term k1 is the forward mass transfer rate constant for the target as it moves from the flow mobile phase region to the stagnant mobile phase at the surface or within the pores of the support, and ka is the association rate constant for the target as it binds to the affinity ligand in the column. This equation shows that the rate-limiting step in the binding of the target to the column can be either mass transfer in the mobile phase, as represented by the term 1/(k1Ve), or adsorption to the affinity ligand, as represented by 1/(kamL). Thus, information can be obtained on the interaction of the target with the affinity ligand if the term 1/(kamL) is made comparable to or larger than 1/(k1Ve) [97].

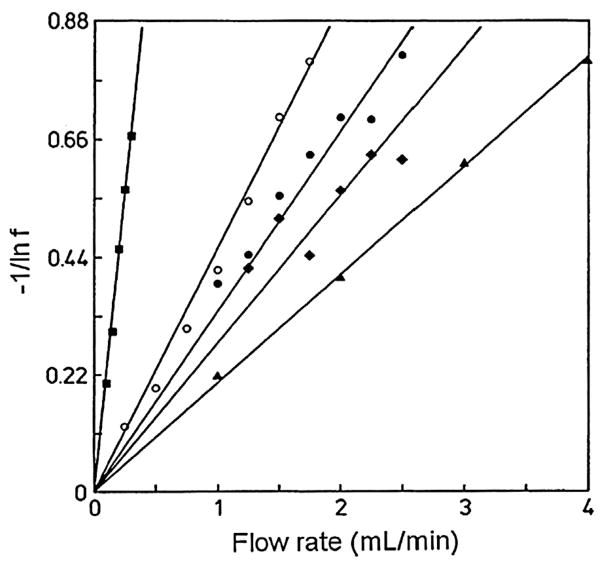

The results for a typical series of split-peak experiments are shown in Fig. 11 [97]. As part of this process, the peak areas for the retained and non-retained fractions of an injected target are first made over a range of flow rates and at various sample concentrations. A plot of −1/ln(f) versus F is then made according to Eq. (12) at each sample concentration, and the measured slopes are extrapolated to an infinitely dilute sample [97,183,184]. This slope is then compared to independent estimates of the mass transfer contribution, 1/(k1Ve), by injecting the same analyte on an inert control column or on a column with rapid association kinetics. If a separate estimate of mL is also available, this process allows 1/(kamL) and ka to be obtained [97]. A key advantage of this approach is it requires only peak area measurements. The main disadvantage is this method tends to be limited to targets and binding agents with relatively slow dissociation kinetics, which generally corresponds with high affinity interactions [2,97].

Fig. 11.

Analysis of split-peak data according to Eq. (12) for injections of rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) onto protein A columns prepared by various immobilization methods and supports. The conditions for each plot were as follows: Schiff base method, 500 Å pore size silica, 22 μg IgG (●); Schiff base method, 500 Å pore size support, 11 μg IgG (●); Schiff base method, 50 Å pore size support, 15 μg IgG (▲); carbonyldiimidazole method, 500 Å pore size support, 2.7 μg IgG (■); and ester/amide method, 500 Å pore size support, 8.2 μg IgG (◆). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [97].

Several applications have appeared for the split-peak method using affinity microcolumns. For instance, this technique was originally used to study and compare the binding kinetics of rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) on various columns containing protein A that was immobilized by different methods (see Fig. 11) [97]. Based on this data it was possible to obtain the association rate constant for IgG with each protein A support [97,183], which later made it possible to optimize and use one of these supports for the analysis of human IgG in clinical samples [185]. This method has also been utilized to determine the apparent association rate constants for IgG on columns containing only protein A or protein G, or a mixture of these two antibody-binding agents [184].

A modified form of the split-peak method has been reported for the case where there is non-linear elution and an adsorption-limited rate for target retention [184,186–190]. This modified approach has been used to examine the association kinetics of HSA with a variety of antibody-based systems [188–190]. In addition, this non-linear method has been utilized to help model and describe the behavior of chromatographic-based competitive binding immunoassays [186,191,192]. Recent work has also expanded this method for use in a frontal analysis format to examine the binding of herbicides with immobilized antibodies [179] and thyroxine with immobilized antibodies or aptamers for this hormone [181].

4.4. Band-broadening studies and peak profiling

There are several methods for studying the kinetics of a biomolecular interaction based on the use of HPAC and affinity chromatography [11]. For example, systems that have low-to-moderate strength interactions (i.e., Ka < 106 M−1) can be examined through the use of band-broadening measurements [11,31]. This technique, known as the plate height method, involves a measurement of the total plate height at several flow rates for a target on a control column containing no binding agent and on an affinity column that contains the immobilized binding agent of interest. These data are then used to determine the plate height contribution due to stationary phase mass transfer (Hk). This term is of interest because it is related to the dissociation rate of the target’s interaction with the immobilized binding agent, as indicated by Eq. (12).

| (12) |

In Eq. (12), u is the linear velocity of the mobile phase in the column, k is the retention factor of the injected target, and kd is the dissociation rate constant between the target and immobilized binding agent. According to this relationship, a plot of Hk versus (uk)/(1 + k)2 should give a linear relationship with a slope that can provide the value of kd [31].

The plate height method has been applied with traditional HPAC columns to study the association and dissociation kinetics of R/S-warfarin and D/L-tryptophan with HSA [121]. This method has also been used to examine the changes in binding of R/S-warfarin and D/L-tryptophan that occur as a result of the change in reaction conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, and organic modifier content of the mobile phase) [121]. Although this method has not been used directly with microcolumns, preliminary work with both silica particles and silica monoliths indicates that plate height measurements suitable for this type of work can be carried out by using 2.1 mm i.d. columns as small as 1–5 mm in length [103,116].

Peak profiling is a variation on this general scheme which directly combines band-broadening data for a target on a control column and an affinity column, as determined under linear elution conditions. This method was first proposed in 1975 [193] and involves a determination of the retention times and total plate heights on the affinity column for the target and a non-retained solute (or for the target on a control column, in the latter case). Such measurements have been made at a single flow rate to find the value of kd for the interaction of the target with an immobilized binding agent, or these measurements can be made at multiple flow rates [44,193–198].

One way that peak profiling data can be analyzed is according to Eq. (13),

| (13) |

where HR is the plate height for the target on the affinity column and HM is the plate height of the non-retained solute on the same column, or for the target on an inert control column. The other terms are the same as defined for Eq. (12). It is possible with this new relationship to either calculate the value of kd at a single flow rate or to make a plot of (HR − HM) versus (uk)/(1 + k)2 for data obtained at several flow rates and to use the slope of the resulting line to get kd [44]. Both Eqs. (12) and (13) are for a situation in which the target has only a single type of interaction with the affinity column. Recently, an expanded set of equations have been described for use with systems that have multi-site interactions with both the support and an affinity ligand [198].

The peak profiling method has been applied to several systems in recent studies. For instance, this method was used to examine the dissociation rate of L-tryptophan from immobilized HSA, giving a value for kd that was consistent with those obtained by other methods [195]. The multi-site method for peak profiling has been used to determine the dissociation rate constants for carbamazepine and imipramine with HSA (see Fig. 12) [194]. A modified form of this technique has also been employed to compare the dissociation rate constants of chiral metabolites for the drug phenytoin with HSA [194]. As work continues in the creation of improved affinity micro-columns, including the use of capillaries [35,36,46–48,92,129] or monoliths [4,73,75,76], it is expected that peak profiling can also be applied to separations that employ such columns.

Fig. 12.

(a) Chromatograms obtained at several flow rates and (b) analysis of the resulting band-broadening data according to Eq. (13) for studies of the dissociation rate of carbamazepine from a 5 cm × 4.6 mm i.d. HSA column by the peak profiling method. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [194].

5. Conclusions

This review discussed various methods based on affinity microcolumns for the study of biomolecular interactions. These microcolumns, which have typical volumes in the mid-to-low microliter range, contain an immobilized binding agent for the selective retention of target compounds. In binding studies, these columns can be used to examine the target’s interaction with the immobilized binding agent or can use this immobilized agent to probe interactions of the target with secondary binding agents in the mobile phase. Microcolumns can be made by decreasing the inner diameter and increasing the column length, as is used in affinity open-tubular capillaries or packed capillaries (i.e., for separations requiring a high efficiency), or by reducing the length of the column (i.e., as can be used in separations that do not require high efficiencies). Either type of microcolumn can be employed with many detection formats and can lead to a significant decrease in the amount of binding agent and support that are needed versus traditional columns for affinity chromatography or HPAC.

Affinity microcolumns can be used in many formats and can provide a wide range of information on biomolecular interactions. Two techniques that are commonly used in these studies are zonal elution and frontal analysis. With these methods, it is possible to determine the degree of binding between a target and binding agent, to measure the equilibrium constant for this interaction, and to estimate the number of binding sites. It is further possible to investigate the ability of a target to compete with other compounds and to look at the effects of changing the reaction conditions, the structure of the binding agent, or the type of target. Other methods that have been used with affinity microcolumns include peak decay analysis, ultrafast affinity extraction and split-peak analysis. The possible use of band-broadening measurements and peak profiling with affinity microcolumns was discussed as well. These techniques can provide data on the association/dissociation rates of a biomolecular interaction and can probe the binding of a target with a soluble binding agent.

The potential advantages and versatility of affinity micro-columns make them attractive tools for biochemical analysis. This is illustrated by the diverse group of applications that has already been reported for affinity microcolumns in the analysis of biomolecular interactions. Applications that were described in this report included studies on the interactions of pharmaceutical agents with serum proteins, the binding of antibodies with their targets and antibody proteins, the screening of libraries for potential enzyme inhibitors, and the binding of lectins with sugars. As further developments appear in the design and use of affinity microcolumns, it is expected that these columns and their associated techniques will continue to grow in importance as means for examining biomolecular interactions in biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were supported by the NIH under grants R01 GM044931 and R01 DK069629, the NSF REU program, and the NSF/EPSCoR program under grant EPS-1004094. R. Matsuda was supported, in part, under a fellowship through the Molecular Mechanisms of Disease program at the University of Nebraska.

References

- 1.Schiel JE, Mallik R, Soman S, Joseph KS, Hage DS. J Sep Sci. 2006;29:719–737. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200500501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaiken IM. Analytical Affinity Chromatography. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hage DS. In: Handbook of HPLC. Corradini D, Katz E, Eksteen R, Shoenmakers P, Miller N, editors. Vol. 4. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1998. pp. 483–498. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mallik R, Hage DS. J Sep Sci. 2006;29:1686–1704. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200600152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwong TC. Clin Chim Acta. 1985;151:193–216. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(85)90082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svensson CK, Woodruff MN, Baxter JG, Lalka D. Clin Pharmacokin. 1986;11:450–469. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198611060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindup WE. In: Progress in Drug Metabolism. Bridges JW, Chasseaud LF, Gibson GG, editors. Taylor & Francis; New York: 1987. pp. 141–185. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters T., Jr . All About Albumin: Biochemistry, Genetics and Medical Applications. New York: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wainer IW. Trends Anal Chem. 1993;12:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter DC, Ho JX. Adv Prot Chem. 1994;45:153–203. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hage DS, Tweed SA. J Chromatogr B. 1997;699:499–525. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herve F, Urien S, Albengres E, Duche JC, Tillement JP. Clin Pharmacokin. 1994;26:44–58. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199426010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan S, Gerson B. Clin Lab Med. 1987;7:279–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barre J, Didey F, Delion F, Tillement JP. Ther Drug Monit. 1988;10:133–143. doi: 10.1097/00007691-198802000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinze A, Holzgrabe U. Bioforum. 2005;28:21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhirkov YA, Piotrovskii VK. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1984;36:844–845. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1984.tb04891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitlam JB, Brown KF. J Pharm Sci. 1981;70:146–150. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600700208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, Zhang L, Zhang X. Anal Sci. 2006;22:1515–1518. doi: 10.2116/analsci.22.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia Z. Curr Pharm Anal. 2005;1:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heegaard NHH, Schou C. In: Handbook of Affinity Chromatography. Hage DS, editor. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. pp. 699–735. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Chen X, Yue Y, Zhang J, Song Y. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:2876–2883. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erim FB, Krak JC. Chromatogr B. 1998;710:205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Busch MHA, Carels LB, Boelens HFM, Kraak JC, Poppe H. J Chromatogr A. 1997;777:311–328. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(97)00369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim H, Austin J, Hage DS. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:956–963. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200203)23:6<956::AID-ELPS956>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Day YSN, Myszka DG. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:333–343. doi: 10.1002/jps.10293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sulkowska A, Bojko B, Rownicka J, Rezner P, Sulkoxski WW. J Mol Struct. 2005;744–747:781–787. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shortridge MD, Mercier KS, Hage DS, Harbison GS, Powers R. J Combin Chem. 2008;10:948–958. doi: 10.1021/cc800122m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohlson S, Hansson L, Larsson PO, Mosbach K. FEBS Lett. 1978;93:5–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80792-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohlson S, Lundblad A, Zopf D. Anal Biochem. 1988;169:204–208. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90275-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zopf D, Ohlson S. Nature. 1990;346:87–88. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hage DS, Chen J. In: Handbook of Affinity Chromatography. Hage DS, editor. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. pp. 595–628. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohlson S, Shoravi S, Fex T, Isaksson R. Anal Biochem. 2006;359:120–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wikström P, Larsson PO. J Chromatogr. 1987;388:123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)94473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiel JE, Hage DS. J Sep Sci. 2009;32:1507–1522. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200800685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calleri E, Fracchiolla G, Montanari R, Pochetti G, Lavecchia A, Loiodice F, Laghezza A, Piemontese L, Massolini G, Temporini C. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1232:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Temporini C, Pochetti G, Fracchiolla G, Piemontese L, Montanari R, Moaddel R, Laghezza A, Altieri F, Cervoni L, Ubiali D, Prada E, Loiodice F, Massolini G, Calleri E. J Chromatogr A. 2013;1284:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.01.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh N, Ravichandran S, Norton DD, Fugmann SD, Moaddel R. Anal Biochem. 2013;436:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mallik R, Yoo MJ, Briscoe CJ, Hage DS. J Chromatogr A. 2010;1217:2796–2803. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohnmacht CM, Schiel JE, Hage DS. Anal Chem. 2006;78:7547–7556. doi: 10.1021/ac061215f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng X, Yoo MJ, Hage DS. Analyst. 2013;138:6262–6265. doi: 10.1039/c3an01315d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tetala KKR, Chen B, Visser GM, van Beek TA. J Sep Sci. 2007;30:2828–2835. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200700356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palcic MM, Zhang B, Qian X, Rempel B, Hindsgaul O. Methods Enzymol. 2003;362:369–372. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)01026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erxleben H, Ruzicka J. Analyst. 2005;130:469–471. doi: 10.1039/b501039j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anguizola J, Joseph KS, Barnaby OS, Matsuda R, Alvarado G, Clarke W, Cerny RL, Hage DS. Anal Chem. 2013;85:4453–4460. doi: 10.1021/ac303734c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]