Abstract

A β-glucan synthase gene was isolated from the genomic DNA of polypore mushroom Sparassis crispa, which reportedly produces unusually high amount of soluble β-1,3-glucan (β-glucan). Sequencing and subsequent open reading frame analysis of the isolated gene revealed that the gene (5,502 bp) consisted of 10 exons separated by nine introns. The predicted mRNA encoded a β-glucan synthase protein, consisting of 1,576 amino acid residues. Comparison of the predicted protein sequence with multiple fungal β-glucan synthases estimated that the isolated gene contained a complete N-terminus but was lacking approximately 70 amino acid residues in the C-terminus. Fungal β-glucan synthases are integral membrane proteins, containing the two catalytic and two transmembrane domains. The lacking C-terminal part of S. crispa β-glucan synthase was estimated to include catalytically insignificant transmembrane α-helices and loops. Sequence analysis of 101 fungal β-glucan synthases, obtained from public databases, revealed that the β-glucan synthases with various fungal origins were categorized into corresponding fungal groups in the classification system. Interestingly, mushrooms belonging to the class Agaricomycetes were found to contain two distinct types (Type I and II) of β-glucan synthases with the type-specific sequence signatures in the loop regions. S. crispa β-glucan synthase in this study belonged to Type II family, meaning Type I β-glucan synthase is expected to be discovered in S. crispa. The high productivity of soluble β-glucan was not explained but detailed biochemical studies on the catalytic loop domain in the S. crispa β-glucan synthase will provide better explanations.

Keywords: β-Glucan, Cell wall, Glucan synthase, Sparassis crispa

The cell wall of fungi is composed of chitin, β-1,3-glucan (hereinafter β-glucan), and glycoproteins as the main components. Chitin is a polymer of N-acetylglucosamine linked through β-1,4-glycosidic bonds. In the case of filamentous fungi, chitin accounts for 10~20% of the total dry weight. Chitin polymers form microfibril structures through intermolecular hydrogen bonds, and the microfibrils enclose the cell membrane to maintain cell integrity. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, three chitin synthases (Chs1, Chs2, and Chs3) are involved in the biosynthesis of chitin [1]. β-Glucan, a predominant cell wall component, is a polymer of glucose linked through β-1,3-glycosidic bonds. It occupies 50% of the fungal dry weight. S. cerevisiae synthesizes β-glucan through the activities of two independent β-glucan synthases (Fks1 and Fks2) using UDP-glucose and a precursor β-glucan as substrates. Membrane-bound Rho I GTPase is known to regulate the activity of Fks1 and Fks2 as a regulatory subunit [2]. In fungi, β-glucan synthase is encoded by a corresponding gene with the size of 5~6 kbp, which expresses a large protein with a size of ~200 kDa [3, 4]. β-Glucan synthase is an integral membrane protein, which consists of two cytosolic domains (C1 and C2) and two transmembrane domains (TM1 and TM2). In the case of Fks1, the catalytic C2 domain is located in the cytoplasmic side of membrane linked to the two TM domains. TM1 and TM2 are composed of six and seven transmembrane α-helices, respectively [5].

Fungal β-glucans, particularly mushroom β-glucans reportedly activate immune system. Some β-glucans have been developed as anti-cancer drugs, such as krestin (Grifola frondosa) [6, 7], lentinan (Lentinula edodes) [8], and schizophyllan (Schizophyllum commune) [9]. These mushroom anti-cancer drugs do not directly kill cancer cells instead suppress cancer cell proliferation by activating immunity within cancer patients. β-Glucans are recognized by the pattern-recognition receptor Dectin-1 on dendritic cells, monocytes, and B cells as a signature of fungal infection [10]. Binding of β-glucans to Dectin-1 eventually leads to the activation of adaptive immune responses, including expression of tumor suppression cytokines [11, 12].

The content of soluble β-glucan, which is of particular importance in immune stimulation, is essentially dependent on mushroom species. Cultivated mushrooms, Pleurotus ostreatus, P. eryngii, P. pulmonarius, and L. edodes, consist of 0.6~1.5% soluble β-glucan on a dry weight basis [13]. The content can vary according to the cultivation conditions, such as the carbon to nitrogen ratio of the substrate, pH, and culture temperature [14]. Interestingly, polypore mushroom Sparassis crispa has been reported to contain an unusually high amount of soluble β-glucan (40% dry weight) in its fruiting body [15]. Hot water or alkali extract of S. crispa displays anti-tumor activity and stimulates hematopoietic responses [16]. S. crispa is a parasitic and saprotrophic mushroom, growing on the roots or basis of oak or conifer trees. It is also considered to be a brown-rot fungus since it does not produce lignin-degrading enzyme [17]. This mushroom has drawn much attention as a soluble β-glucan producer, but further study has been impeded due to its extremely slow growth rate. As an alternative, the production of β-glucan through mycelial culture has been recently examined by introducing a high β-glucan producing mutant strain [18].

In this study, the β-glucan synthase gene from a S. crispa strain was isolated and its primary structure was examined by comparative study with known fungal β-glucan synthase genes in order to provide an explanation for the unusual high β-glucan productivity of S. crispa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions

S. crispa IUM4010 was obtained from the Culture Collection of Wild Mushrooms (CCWM), University of Incheon, Korea. The strain was maintained on potato-dextrose agar medium (Ventech Bio Co., Eumseong, Korea). For the liquid culture, the mushroom mycelia were cultured in potato dextrose broth (PDB; Ventech Bio Co.) with gentle shaking at 25℃ for 2~3 wk.

Extraction of genomic DNA

Genomic DNA was extracted from the mushroom mycelia grown in PDB using the previously described method [19]. In brief, the mushroom mycelia were harvested and then ground with a mortar and pestle. The ground powder was then suspended in 0.5mL of lysing buffer (50mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.2M EDTA, and 10 µg/mL of proteinase K; Sigma-Aldrich Co. St. Louis, MO, USA) to a final concentration of 1 g/mL, after which the suspension was incubated for 10 min at 65℃. The clarified supernatant was obtained by centrifugation. The nucleic acids in the solution were precipitated with 40% isopropanol. The precipitates were dried and then resuspended in 0.2mL of TE buffer containing 0.05mL/mL of RNase. The solution was incubated at 50℃ for 10min. Proteins in the solution were removed by treatment with 0.2mL of chloroform: isoamylalcohol (24 : 1) solution. The isopropanol precipitates were suspended in 0.1 mL of TE buffer for further analysis.

Isolation of β-glucan synthase gene

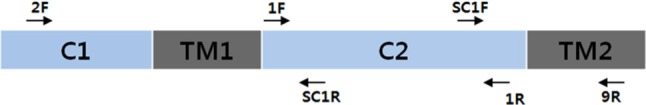

To isolate the β-glucan synthase gene from genomic DNA, degenerated primer sets were designed from a conserved C2 domain region of 19 fungal β-glucan synthase gene sequences (1F, 1R in Table 1, Fig. 1). PCR using the primer set yielded a 1.5 kbp product. The sequence of the C2 domain product was determined, and then new specific primers (SC1R, SC1F) targeting the outside of C2 domain were generated. The second PCR reactions were performed using combinations of the specific primers and degenerated primers (2F, 9R). The primer sets 2F/SC1R and SC1F/9R targeted 5' and 3' regions of the C2 domain, respectively. The PCR reactions yielded a 2 kbp DNA band for the 5' region and a 1.5 kbp band for the 3' region. The DNA sequences for both products were determined and assembled with the C2 domain sequence, yielding an incomplete β-glucan synthase gene sequence with a size of 4,905 bp. The remaining 5' end region was further determined by inverse PCR technology [20]. As a result, the sequence of the S. crispa β-glucan synthase gene with a size of 5,502 bp was determined and deposited into Genebank (accession No. KJ187309).

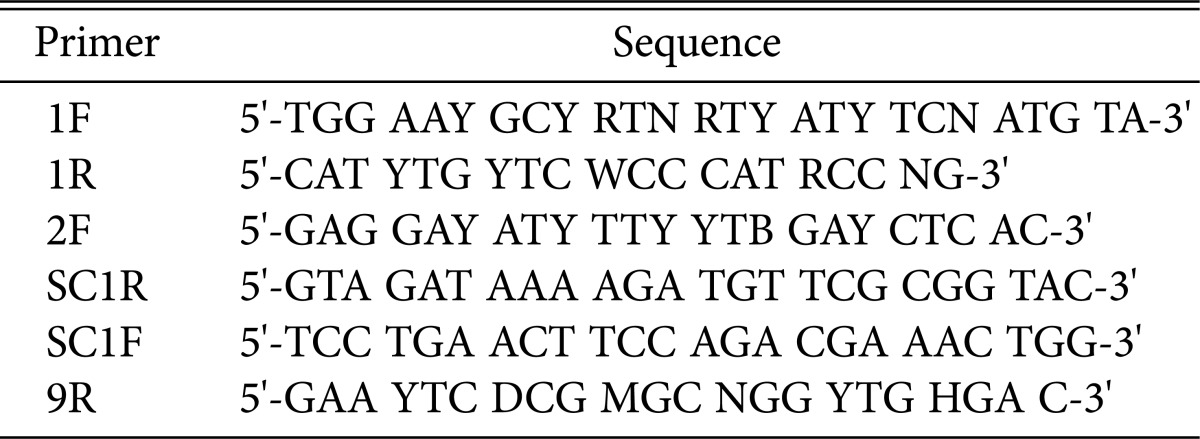

Table 1.

Primers for the cloning of β-glucan synthase gene in Sparassis crispa

Fig. 1.

Locations of primers targeting the β-glucan synthase gene in Sparassis crispa. Two catalytic domains are marked as C1 and C2. The transmembrane domains are marked as TM1 and TM2.

Analysis of β-glucan synthase gene structure

The exon arrangement of the S. crispa β-glucan synthase gene was analyzed by FGENESH software (http://linux1.softberry.com/) [21] using Coprinopsis cinerea genome as a reference. Transmembrane domain of the β-glucan synthase protein was analyzed by Phobius software (http://phobius.sbc.su.se/) [22]. Phylogenetic analysis with the fungal β-glucan synthases was conducted using MEGA ver. 2.0 software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Primary structure of the S. crispa β-glucan synthase gene

The DNA sequence with a size of 5,502 bp for the S. crispa β-glucan synthase gene was determined. Sequence comparison analysis of multiple fungal β-glucan synthase genes revealed that the determined sequence was incomplete, lacking approximately 400 bp at the 3' end region. The β-glucan synthase gene was analyzed by the FGENESH program to predict the open reading frame using the C. cinerea genome as the reference. As a result, the β-glucan synthase gene was found to consist of 10 exon sequences separated by nine introns. The predicted size of the mRNA was 4,728 bp. The mRNA encoded a polypeptide consisting of 1,576 amino acid residues. Since mushroom β-glucan synthases of this type are generally composed of 1,640~1,650 amino acid residues, the S. crispa β-glucan synthase in this study is estimated to be devoid of approximately 70 amino acids at its C-terminus. However, the protein regions critical for enzyme function, including the active site, are mostly contained within the 1,500 amino acid residues for fungal β-glucan synthase [5]. The amino acid sequence for S. crispa β-glucan synthase is estimated to carry most of the information required for the analysis of enzyme function.

Domain analysis for S. crispa β-glucan synthase

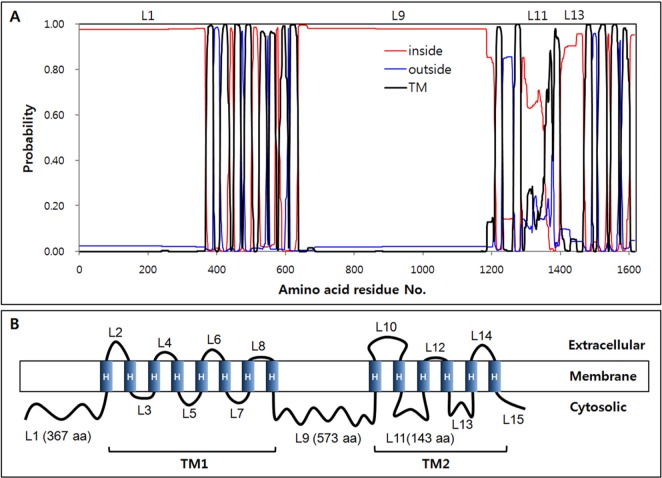

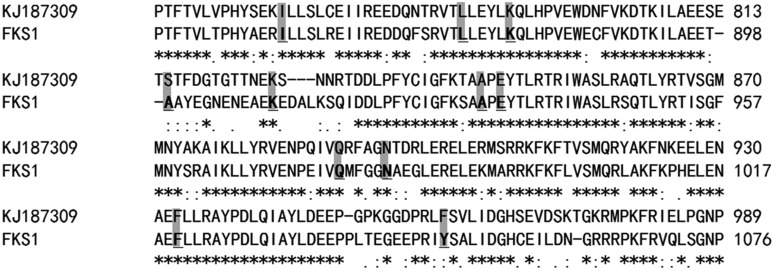

Fungal β-glucan synthase is an integral membrane protein, consisting of two cytosolic and two transmembrane domains [1, 23]. Topology of S. crispa β-glucan synthase was analyzed by the Phobius program to predict the functional domain regions. As shown in Fig. 2A, S. crispa β-glucan synthase was predicted to consist of 15 loops (L1~L15) and 14 transmembrane α-helices (H1~H14). Catalytic domains C1 and C2, homologous to Fks1, were found in L1 and L9, respectively. The two domains were separated by the transmembrane domain TM1, which was shown to comprise eight transmembrane α-helices (H1~H8). TM2, composed of six transmembrane α-helices (H7~H14), was located at the C-terminus of the protein (Fig. 2B). The large loop structures L1, L9, and L11 with lengths of 367, 573, and 143 aa, respectively, were located at the cytosolic side of the membrane, implying their function in the synthesis of β-glucan. In the yeast homologue Fks1, the L9 loop was reported to play a critical role in enzyme catalysis [24]. Mutations in the core catalytic regionof the Fks1 L9 loop, ranging 830~1,050 aa, caused more than 80% reduction in catalytic activity, as shown by the mutant strains fks1-1144 (L872F, E907K, N982S) and fks1-1154 (K877N, A899S, Q977P) [25]. The L9 loop of S. crispa β-glucan synthase was highly homologous to that of Fks1 (Fig. 3). The amino acid residues reported to affect the catalytic activity of Fks1 were well conserved in S. crispa β-glucan synthase (Fig. 3, shaded amino acids).

Fig. 2.

Topology of the β-glucan synthase from Sparassis crispa. A, Predicted topology by Phobius software; B, Schematic description based on the predicted topology. Random loops were designated as L1~L15. Transmembrane α-helices were marked as H in panel (B).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of core catalytic regions in the L9 loops of Sparassis crispa (KJ187309) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (FKS1). The shaded amino acids were reported to be important for catalytic function of FKS1 [24].

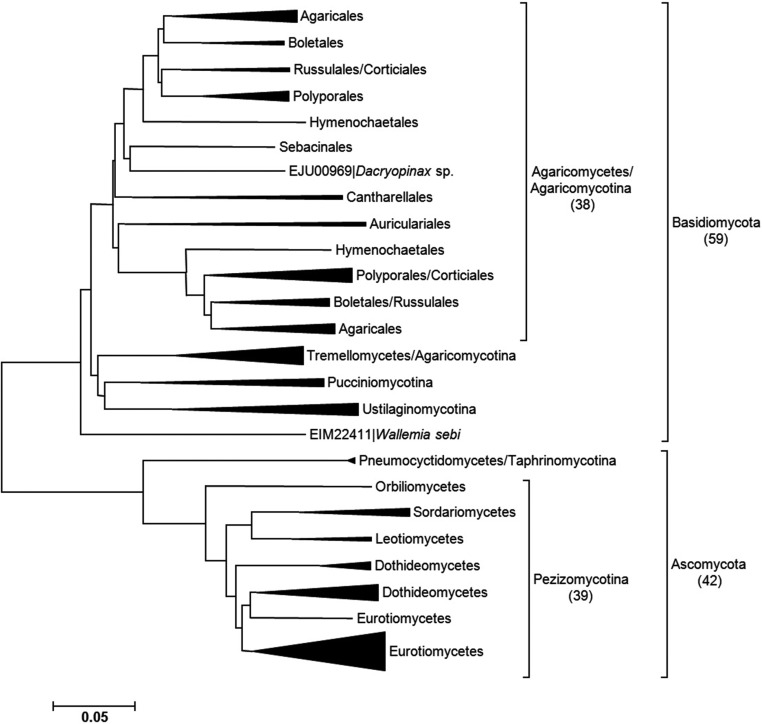

Analysis of fungal β-glucan synthase family

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the amino acid sequences of 101 fungal β-glucan synthases registered in Genebank in order to elucidate the diversity of β-glucan synthase as well as the exact position of S. crispa β-glucan synthase. All fungal β-glucan synthases were categorized into two phyla (Ascomycota and Basidiomycota) of the classification system (Fig. 4). In Ascomycota, most of the β-glucan synthases belonged to the subphylum Pezizomycotina. In Basidiomycota, the enzyme was distributed to four different subphyla, but most belonged to the class Agaricomycetes in the subphylum Agraricomycotina (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of fungal β-glucan synthases. The number in the parenthesis is the number of sequences belonging to the corresponding group.

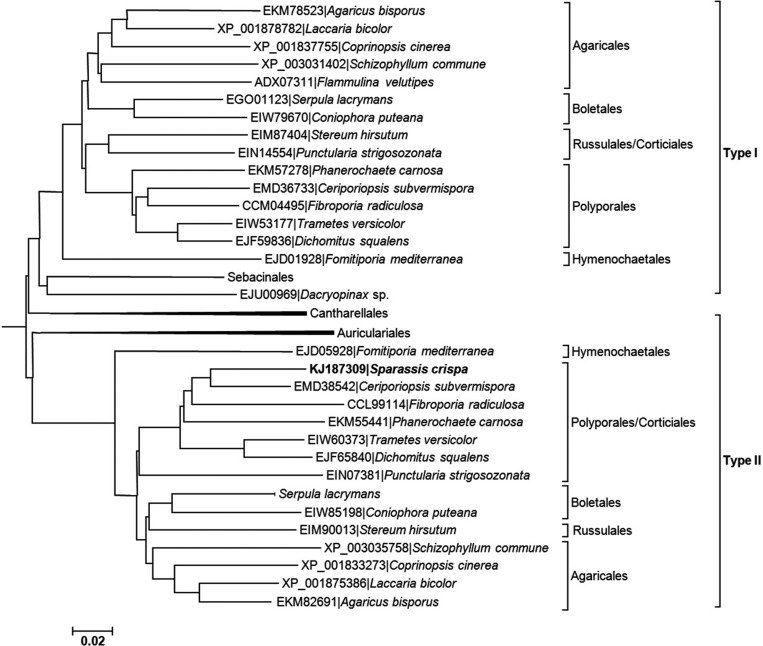

Those mushrooms only in the class Agaricomycetes, including Agaricus bisporus, Trametes versicolor, Schizophyllum commune, and C. cinerea, were found to contain two distinct types of β-glucan synthases (Fig. 5). For example, A. bisporus carries two different β-glucan synthases, EKM78523 and EKM82691. Therefore, having two different types of β-glucan synthases in the same cell appears to be a common characteristic of Agaricomycetes mushrooms. The reason why only these mushrooms display this feature is not clear, but it may imply gene duplication in the common ancestor of Agaricomycetes and subsequent divergent evolution of each β-glucan synthase gene in the same organism. S. crispa β-glucan synthase in this study belonged to Type II family (Fig. 5), meaning Type I β-glucan synthase is expected to be discovered in S. crispa.

Fig. 5.

Sequence analysis of β-glucan synthases belonging to the class Agaricomycetes. The β-glucan synthase from Sparassis crispa belonged to Type II.

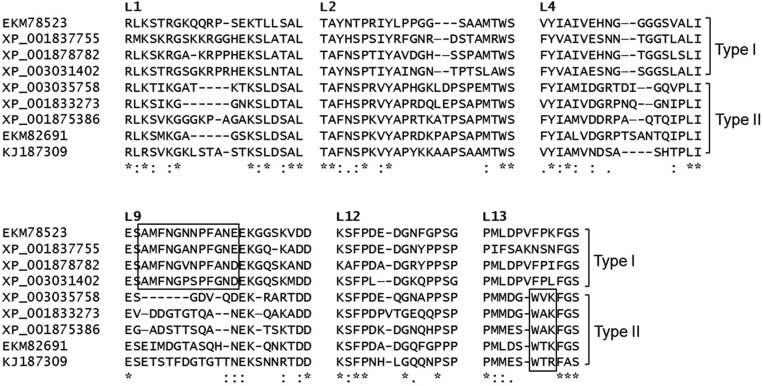

Characteristics of Type I and Type II β-glucan synthases

Multiple sequence alignment analysis was conducted on the two different types of β-glucan synthases from A. bisporus, C. cinerea, Laccaria bicolor, S. commune, and S. crispa. TM domains were mostly conserved regardless of type. However, we detected highly variable, but specific for Type I or Type II family, regions in the loops, L1, L2, L4, L9, L12, and L13 (Fig. 6). In the L9 loop, a conserved sequence motif (AMFNGXNPFAXE/D) was discovered in Type I, whereas it was deleted or randomized in Type II (Fig. 6, boxed region in L9). A distinct sequence motif for Type II was also discovered. The consensus sequence WXK/R in L13 was a specific sequence signature for Type II β-glucan synthase. S. crispa β-glucan synthase carries this signature as WTR.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the loop regions in Type I and Type II β-glucan synthases. The boxed regions contain type-specific signatures.

S. cerevisiae, a member of Ascomycota, produces two β-glucan synthases from two independent genes, FKS1 and FKS2. However, these enzymes are highly homologous proteins and do not belong to any type of Agaricomycetes β-glucan synthase. The L9 catalytic loop regions for both enzymes are virtually identical, implying that both enzymes may have similar catalytic activity. FKS1 is primarily expressed in the vegetative growth, whereas FKS2 is expressed under stress conditions, including starvation, sporulation, and mating [26]. Therefore, S. cerevisiae β-glucan synthases are catalytically identical but functionally independent enzymes.

Mushrooms belonging to Agaricomycetes express two types of β-glucan synthases, that are potentially different in terms of catalytic activity as suggested by different amino acid arrangements in the catalytic loop region, may function in different developmental stages. Transcriptome analyses of A. bisporus H97 in different developmental stages have shown that Type II β-glucan synthase (XP_006458137, a homologue of EKM78523) was constantly expressed throughout the developmental stages whereas Type I β-glucan synthase (XP_006455356, a homologue of EKM82691) was highly expressed in the fruiting body stage [27]. Further studies will clarify the detailed role of these enzymes. The exceptionally high production of soluble β-glucan by S. crispa was not fully explained. Comparative biochemical study with various Agaricomycetes β-glucan synthases will provide better explanations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by GyeongNam Technopark program (#70011463), the Ministry of Knowledge Economy, Korea.

References

- 1.Orlean P. Architecture and biosynthesis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall. Genetics. 2012;192:775–818. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.144485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang MS, Cabib E. Regulation of fungal cell wall growth: a guanine nucleotide-binding, proteinaceous component required for activity of (1/3)-β-D-glucan synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:5808–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan GC, Chan WK, Sze DM. The effects of β-glucan on human immune and cancer cells. J Hematol Oncol. 2009;2:25. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-2-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ujita M, Katsuno Y, Szuki K, Sugiyama K, Takeda E, Hara A, Yokoyama E. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the β-1,3-glucan synthase catalytic subunit gene from a medicinal fungus, Cordyceps militaris. Mycoscience. 2006;47:98–105. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson ME, Edlind TD. Topological and mutational analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fks1. Eukaryot Cell. 2012;11:952–960. doi: 10.1128/EC.00082-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakazato H, Koike A, Saji S, Ogawa N, Sakamoto J. Efficacy of immunochemotherapy as adjuvant treatment after curative resection of gastric cancer. Lancet. 1994;343:1122–1126. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maehara Y, Tsujitani S, Saeki H, Oki E, Yoshinaga K, Emi Y, Morita M, Kohnoe S, Kakeji Y, Yano T, et al. Biological mechanism and clinical effect of protein-bound polysaccharide K (KRESTIN®): review of development and future perspectives. Surg Today. 2012;42:8–28. doi: 10.1007/s00595-011-0075-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Li S, Wang X, Zhang L, Cheung PC. Advances in lentinan: isolation, structure, chain conformation and bioactivities. Food Hydrocoll. 2011;25:196–206. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mansour A, Daba A, Baddour N, El-Saadani M, Aleem E. Schizophyllan inhibits the development of mammary and hepatic carcinomas induced by 7,12 dimethylbenz(α)anthracene and decreases cell proliferation: comparison with tamoxifen. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1579–1596. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1224-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers NC, Slack EC, Edwards AD, Nolte MA, Schulz O, Schweighoffer E, Williams DL, Gordon S, Tybulewicz VL, Brown GD, et al. Syk-dependent cytokine induction by Dectin-1 reveals a novel pattern recognition pathway for C type lectins. Immunity. 2005;22:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodridge HS, Simmons RM, Underhill DM. Dectin-1 stimulation by Candida albicans yeast or zymosan triggers NFAT activation in macrophages and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:3107–3115. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palm NW, Medzhitov R. Pattern recognition receptors and control of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:221–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rop O, Mlcek J, Jurikova T. Beta-glucans in higher fungi and their health effects. Nutr Rev. 2009;67:624–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang JC, Hu SH, Liang ZC, Yeh CJ. Optimization for the production of water-soluble polysaccharide from Pleurotus citrinopileatus in submerged culture and its antitumor effect. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;67:759–766. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1833-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura T. Natural products and biological activity of the pharmacologically active cauliflower mushroom Sparassis crispa. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:982317. doi: 10.1155/2013/982317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohno N, Miura NN, Nakajima M, Yadomae T. Antitumor 1,3-beta-glucan from cultured fruit body of Sparassis crispa. Biol Pharm Bull. 2000;23:866–872. doi: 10.1248/bpb.23.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HJ, Kim JS, Yi CK. Decay damage of Japanese larch (Larix leptolepis) caused by two butt-rot fungi, Phaeolus schweinitzii and Sparassis crispa. J Korean For Soc. 1990;79:138–143. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SR, Kang HW, Ro HS. Generation and evaluation of high β-glucan producing mutant trains of Sparassis crispa. Mycobiology. 2013;41:159–163. doi: 10.5941/MYCO.2013.41.3.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le QV, Won HK, Lee TS, Lee CY, Lee HS, Ro HS. Retrotransposon microsatellite amplified polymorphism strain fingerprinting markers applicable to various mushroom species. Mycobiology. 2008;36:161–166. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2008.36.3.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin VJ, Mohn WW. An alternative inverse PCR (IPCR) method to amplify DNA sequences flanking Tn5 transposon insertions. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;35:163–166. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(98)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solovyev V, Kosarev P, Seledsov I, Vorobyev D. Automatic annotation of eukaryotic genes, pseudogenes and promoters. Genome Biol. 2006;7(Suppl 1):S10. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-s1-s10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Käll L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer EL. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douglas CM, Foor F, Marrinan JA, Morin N, Nielsen JB, Dahl AM, Mazur P, Baginsky W, Li W, El-Sherbeini M, et al. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae FKS1 (ETG1) gene encodes an integral membrane protein which is a subunit of 1,3-beta-D-glucan synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12907–12911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dijkgraaf GJ, Abe M, Ohya Y, Bussey H. Mutations in Fks1p affect the cell wall content of β-1,3- and β-1,6-glucan in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2002;19:671–690. doi: 10.1002/yea.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okada H, Abe M, Asakawa-Minemura M, Hirata A, Qadota H, Morishita K, Ohnuki S, Nogami S, Ohya Y. Multiple functional domains of the yeast l,3-beta-glucan synthase subunit Fks1p revealed by quantitative phenotypic analysis of temperature-sensitive mutants. Genetics. 2010;184:1013–1024. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.109892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazur P, Morin N, Baginsky W, el-Sherbeini M, Clemas JA, Nielsen JB, Foor F. Differential expression and function of two homologous subunits of yeast 1,3-beta-D-glucan synthase. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5671–5681. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morin E, Kohler A, Baker AR, Foulongne-Oriol M, Lombard V, Nagye LG, Ohm RA, Patyshakuliyeva A, Brun A, Aerts AL, et al. Genome sequence of the button mushroom Agaricus bisporus reveals mechanisms governing adaptation to a humic-rich ecological niche. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:17501–17506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206847109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]