Abstract

Approximately 20% of patients with multiple myeloma (MM) have renal failure at diagnosis, and about 5% are dialysis-dependent. Many of these patients are considered ineligible for autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-HSCT) because of a high risk of treatment-related toxicity. We evaluated the outcome of 46 patient with MM and renal failure, defined as serum creatinine >2 mg/dL sustained for >1 month before the start of preparative regimen. Patients received auto-HSCT at our institution between September 1997 and September 2006. Median serum creatinine and creatinine clearance (CrCl) at auto-HSCT were 2.9 mg/dL (range: 2.0–12.5) and 33 mL/min (range: 8.7–63), respectively. Ten patients (21%) were dialysis-dependent. Median follow-up in surviving patients was 34 months (range: 5–81). Complete (CR) and partial responses (PR) after auto-HSCT were seen in 9 (22%) and 22 (53%) of the 41 evaluable patients, with an overall response rate of 75%. Two patients (4%) died within 100 days of auto-HSCT. Grade 2–4 nonhematologic adverse events were seen in 18 patients (39%) and included cardiac arrythmias, pulmonary edema, and hyperbilirubinemia. Significant improvement in renal function, defined as an increase in flomerular filtration rate (GFR) by 25% above baseline, was seen in 15 patients (32%). Kaplan-Meier estimates of 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 36% and 64%, respectively. In conclusion, auto HSCT can be offered to patients with MM and renal failure with acceptable toxicity and with a significant improvement in renal function in approximately one-third of the transplanted patients. In this analysis, a melphalan (Mel) dose of 200 mg/m2 was not associated with an increase in toxicity or nonrelapse (Mel) mortality (NRM).

Keywords: Myeloma, Renal failure, Autologous

INTRODUCTION

Renal insufficiency is frequently observed in multiple myeloma (MM). Up to 20% of newly diagnosed patients have renal failure, defined as serum creatinine >2 mg/dL [1,2]. Several factors contribute to renal failure in MM patients, including monoclonal light-chain-induced proximal tubular damage, hypercalcemia, dehydration, infection, hyperuricemia, and the use of nephrotoxic drugs [2]. Amyloid deposition and plasma cell infiltration are less frequent causes for renal impairment [3]. Renal failure was a predictor of poor prognosis in early chemotherapy trials for MM. Patients requiring dialysis were reported to have a poorer prognosis [4]. Renal failure is also considered a marker of high tumor burden and inadequate therapy [5].

High-dose chemotherapy (HDT) using melphalan (Mel) 200 mg/m2 with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-HSCT) improves the outcome of patients with MM in terms of remission rates and survival with a nonrelapse mortality (NRM) of <5% [6,7]. Because of concerns about higher rates of treatment-related toxicity and NRM, patients with renal insufficiency are frequently excluded from HDT protocols [8]. A few recent reports have addressed the role of HDT and auto-HSCT in patients with MM and concurrent renal failure, and showed that this treatment is feasible in patients with renal insufficiency, even in a dialysis-dependent setting [8–10]. The objective of this retrospective analysis study was to evaluate the safety and feasibility of this approach in patients with myeloma and renal failure, who received HDT and auto-HSCT at our institution. We also analyzed the impact of Mel dose on the outcome, and the reversibility of renal failure.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Forty-six patients with MM and concomitant renal failure, defined as a serum creatinine ≥2 mg/dL sustained for more than 1 month before the start of preparative regimen HSCT. Patients received high-dose melphalan followed by auto-HSCT were included in this analysis. Patients received auto-HSCT between April 1997 and September 2006. Ten patients (21%) were hemodialysis-dependent. Median age at auto-HSCT was 55 years (range: 29–72). Forty-two patients were <65 years old and 4 were ≥65 years old. Median interval between diagnosis and transplant was 12 months (range: 5–107). All patients gave written informed consent before auto-HSCT, which was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Treatment

Peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) were mobilized and collected following granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) alone (36) or chemotherapy + G-CSF (10) [11]. All 46 patients received high-dose Mel on days −4 and −3. Thirty-three patients received a Mel dose of 200 mg/m2, 9 patients received 180 mg/m2, and 4 patients received 140 mg/m2 [11,12]. Patients with older age or worse renal impairment were not intended to receive a lower Mel dose. Before this analysis, the common practice of some attending physicians was to use a lower mel dose for patients with impaired renal function, a practice that was not uniform and hence the discrepancy in doses. Unmanipulated autologous stem cells were infused 48 hours later. All patients received G-CSF, 5 μg/kg/day from day +1 until the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was 0.5 × 109/L for 2 consecutive days, in accordance with our departmental guidelines. Blood products were given for hemoglobin ≤8 g/dL and platelets <20 × 109/L. Hemodialysis was administered as indicated in dialysis-dependent patients. Mucositis prophylaxis included standard mouth care and prophylactic antimicrobial agents according to standard departmental guidelines. None of the patients receive keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) for mucositis prophylaxis.

Renal Failure

Renal failure was defined as serum creatinine ≥2 mg/dL sustained for >1 month before the start of preparative regimen [8,9,13,14]. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was derived from the serum creatinine values by the Cockcroft Gault formula. This formula is considered a Level A recommendation for accurate measurement of renal function [15]. The data on patient’s sex, height, and weight at the time of transplant were taken into consideration for baseline GFR calculations. GFR was calculated for each patient at baseline (pretransplant) and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after auto-HSCT. Based on the baseline GFR at the initial diagnosis the patients were subgrouped as chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages 3 to 5 (Table 1) according to the National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI initiative) [16].

Table 1.

Chronic Kidney Disease Staging*

| Stage | Description | GFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 |

|---|---|---|

| —† | At increased risk | ≥60 (with chronic kidney disease risk factors) |

| 1 | Kidney damage: normal or increased GFR | ≥90 |

| 2 | Kidney damage, mild decrease in GFR | 60–89 |

| 3 | Moderately decreased GFR | 30–59 |

| 4 | Severely decreased GFR | 15–29 |

| 5 | Kidney failure | <15 (or dialysis) |

GFR indicates glomerular filtration rate.

National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative Classification, Prevalence, and Action Plan for Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease.

Stages 1 to 5 indicate patients with chronic kidney disease; the first row, without a stage number, indicates patients at increased risk for developing chronic kidney disease.

Chronic kidney disease is defined as either kidney damage or GFR less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 for 3 or more months.

Kidney damage is defined as pathologic abnormalities or markers of damage, including abnormalities in blood or urine tests or imaging studies.

Improvement in renal function was defined as an increase in GFR by ≥25% compared to the baseline. Patients were also grouped according to dialysis dependency status.

Response Criteria

The european group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) response criteria were used to define complete remission (CR), partial response (PR), and relapse [17]. CR was defined as the absence of original monoclonal protein in urine and serum by immunofixation, <5% plasma cells in marrow aspirate, and no increase in the size or number of lytic bony lesions. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as 1 of the following: (1) >25% increase in serum or urine monoclonal protein, or plasma cells in the bone marrow, or (2) increase in the size or number of lytic bony lesions. All responses were in reference to auto-HSCT.

Statistical Methods

The primary endpoints were overall survival (OS) and NRM at day +100 and 1 year after transplantation. Outcomes were estimated starting on the day of auto-HSCT. NRM was defined as death occurring in the absence of progression or relapse of malignancy, and was estimated using the cumulative incidence method considering disease progression as a competing risk. Actuarial OS and progression-free survival (PFS) were estimated by the method of Kaplan-Meier. Outcomes according to pretransplantation characteristics were compared on univariate analysis using the Cox’s proportional hazards model. Multivariate analysis was not possible because of sample size considerations. All p values presented are 2-sided. Statistical analyses were carried out using Stata 8.0.

RESULTS

Patients

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the 46 patients included in this analysis. The median age was 54 years (range: 29–72). Median number of prior treatments was 3 (range: 0–6). Ten patients (21%) were dialysis-dependent at the time of auto-HSCT, 8 on hemodialysis and 2 on peritoneal dialysis. Thirty-three patients received Mel 200 mg/m2, whereas 13 patients received a Mel dose of either 140 or 180 mg/m2. There was no association between M dose and the following: severity of renal failure/dialysis dependence (P =.57); or age >65 years (P =.31).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 46 Patients Undergoing Auto-HSCT While in Renal Failure

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Males | 31 (67%) |

| Median age (range) | 56 (29–72 years) |

| Durie-Salmon stage III | 27 (56%) |

| Dialysis dependence | 10 (22%)* |

| Light chain-only disease | 25 (54%) |

| Albumin <4 g/L | 29 (63%) |

| LDH >618 U/L | 17 (37%) |

| β2M > 8 mg/L | 23 (50%) |

| Median prior chemotherapies (range) | 3 (0–6) |

| Median CD34 cells ×106/kg (range) | 4.47 (1.4–9.7) |

| Cytogenesis | |

| Abnormal | 10 (21%) |

| Normal | 27 (56%) |

| Unknown | 9 (23%) |

| Response to prior chemotherapy | |

| Partial response | 27(58%) |

| Minimal response | 8 (18%) |

| Nonresponder | 8 (18%) |

| Progressive | 2 (4%) |

| Unknown | 1 (2%) |

| Melphalan dose | |

| 180 mg/m2 | 9 (29%) |

| 200 mg/m2 | 33 (65%) |

| 140 mg/m2 | 4 (6%) |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant | |

| ≤12 months | 28 (61%) |

| >12 months | 18 (39%) |

| Mobilization regimen | |

| G-CSF only | 36 (78%) |

| Chemo + G-CSF | 10 (22%) |

LDH indicates lactic dehydrogenase; β2M, beta 2 microglobulin; G-CSF, granulocyte colony stimulating factor; auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Two patients were on peritoneal dialysis.

Stem Cell Mobilization and Engraftment

PBSCs were mobilized with G-CSF alone in 36 cases and with chemotherapy + G-CSF in 10 cases. Ten (21%) patients with high tumor burden received chemotherapy + G-CSF 10 μg/kg/day, with modified CVAD regimen (Cy, vincristine, adriamycin, and dexamethasone) to achieve optimal cytoreduction. An adequate number of CD34+ cells (>2 × 106/kg ) were collected from all 46 patients. Median times to neutrophil (ANC ≥0.5 × 109/L) and platelet engraftment (>50 × 109/L) were 10 (range: 9–18) and 12 (range: 8–81) days, respectively.

Treatment-Related Toxicity

Two patients died of nonrelapse within 100 days (100-day NRM: 4%) and a total of 3 patients had died at 1 year (1 year NRM: 7%). None of the patients receiving Mel 200 mg/m2 died in the first 100 days (100-day NRM 0%) versus 2 of 13 in the who received either 140 or 180 mg/m2 (P =.07). One patient died of sepsis/multiorgan failure, and 1 from pulmonary failure/idiopathic pneumonia syndrome. The cause of death was not known in 1 patient, who died at an outside institution. Grade II/IV nonhematologic toxicity was reported in 18 (39%) patients. None of the 10 dialysis-dependent patients died of nonrelapse causes. There was no significant difference in grade II–IV toxicity between dialysis-dependent and dialysis independent patients (13/36 versus 5/10, P = .4). The adverse events included cardiac arrythmias, pulmonary edema, hyperbilirubinemia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The most common toxicities were diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and dysphagia. Severe mucositis (grade >3) was seen in only 6% of patients.

Clinical Response and Survival

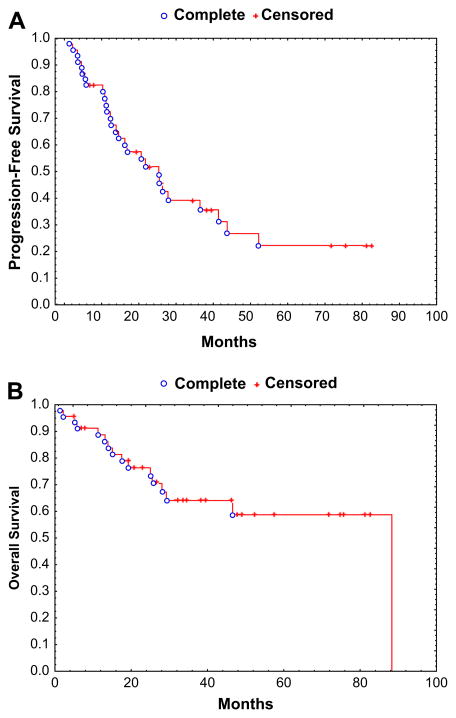

Median follow-up among surviving patients was 34 months (range: 5–81). CR and PR were seen in 9 (22%) and 22 (53%) of the 41 evaluable patients, respectively, with an overall response rate (ORR) of 75% from the time of auto-HSCT. As of last follow-up, 16 patients have died. Median PFS was 25 months, and median OS has not been reached. Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates of 3-year PFS and OS were 36% and 64%, respectively. Thirty patients (62.5%) are still alive after a median follow-up of 34 months, and 18 patients (39%) are alive and progression free.

Figure 1.

(A) Kaplan-Meier estimate of progression-free survival in 46 patients receiving auto-HSCT for MM and renal failure. (B) Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival in 46 patients receiving auto-HSCT for MM and renal failure.

Renal Function

Fifteen patients (32%) experienced a sustained improvement in renal function, defined as an increase in GFR by 25% above baseline on 2 separate occasions, 3 months apart. There was a downstaging of renal failure in 10 patients (21%). However, none of the 10 dialysis-dependent patients were able to attain independence from dialysis. The OS was not affected by the stage of CKD (P = .9).

Prognostic Factors

Serum creatinine prior to auto-HSCT, disease status at auto-HSCT, dialysis-dependence, stage of chronic renal disease, Mel dose, or serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) did not emerge as significant predictors of PFS or OS. This retrospective analysis, however, was not powered to detect the impact of various prognostic factors in a small and heterogeneous population.

DISCUSSION

Renal failure is a well-known complication of MM and is considered a marker for poor prognosis [5]. Several randomized trials support the role of HDT and auto-HSCT as standard treatment for MM because of its association with a higher CR rate, and longer event-free survival (EFS) and OS [6,7]. Patients with concomitant renal failure are generally excluded from this treatment because of an increased risk of morbidity and mortality. These morbidities include infections, encephalopathy, and mucositis. Some studies have reported a 5% to 29% risk of NRM in this patient population [18]. Badros et al. [9] reported an early NRM of 5% with Mel 140 mg/m2, and 7% with Mel 200 mg/m2. A report from the same institution by Lee et al. [14] reported a 6-month NRM of 11% in 59 dialysis-dependent patients. Three other studies reported an NRM of 17%, 18.5%, and 29% [8,10,19]. Our study, in comparison, reports an NRM of only 4% at 100 days, and 6% at 1-year post-HSCT. In our report, only 1 of 33 patients receiving Mel 200 mg/m2 died of nonrelapse causes, which was not different from the NRM seen at lower Mel doses of 140 mg/m2 (1 of 4) and 180 mg/m2 (1 of 9). Notably, there was no NRM in 10 dialysis-dependent patients after a 1-year follow-up. This improvement in NRM may be because of patient selection because these patients other than renal failure were acceptable candidates for HDT with adequate vital organ function. An improvement in supportive care measures including antimicrobial and mucositis prophylaxis may also have contributed to low treatment-related mortality (TRM).

Auto-HSCT in patients with MM and renal failure has been associated with partial or complete recovery of renal function, even in dialysis-dependent patients [8–10,14]. Lee et al. [14] reported an improvement in renal function manifested as dialysis independence in 13 of the 54 evaluable patients (24%). In contrast, Badros et al. [9] reported a partial recovery of renal function in only 2 of the 38 dialysis-dependent patients. In our series, 15 of 46 (32%) experienced a sustained and quantifiable improvement in renal function. There was downstaging of renal failure in 10 patients (21%). Furthermore, 3 of the 10 dialysis-requiring patients also achieved an improvement in renal function, although none of them achieved independence from dialysis. That may be related to irreversible renal damage or the duration of renal failure. Renal failure or dialysis did not interfere with PBSC mobilization or collection in this cohort of patients, and an average of >4 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg were collected. The time to neutrophil and platelet engraftment was comparable to patients with normal renal function [20].

Significant cardiac, pulmonary, and neurologic toxicity have been reported with a Mel dose of 200 mg/m2 [9], and a reduced dose, 140 mg/m2, was recommended. In this report, even with a Mel dose of 200 mg/m2 in 33 of 46 patients, grade II/IV nonhematologic toxicity was seen in 18 (39%) patients, with most of adverse events being mild and reversible. Some of the common events were diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and dysphagia. This lower rate of adverse events may be related to improvements in supportive care, although suboptimal documentation of adverse events cannot be ruled out because of retrospective nature of this analysis. We compared the outcome of this analysis with the outcome of 48 MM patients who received Mel 200 mg/m2 and had serum creatinine of<2 mg and were treated between 2004 and 2006. Although not a direct comparison, the outcome did not appear to be significantly different between the 2 groups. The 100-day NRM, ORR, 3-year PFS, and OS in the group with normal function were 0%, 85%, 25%, and 35, respectively. In comparison, the 100-day NRM, ORR, 3-year PFS, and OS were 0%, 85%, 36%, and 64%, respectively, in the current analysis [21].

Our study had the inherent limitations of a retrospective analysis, including the variability in Mel dose and disease status and a relatively small number of patients. It would be helpful to develop a standardized regimen tailored for patients with impaired renal function. Future prospective clinical trials may address the optimal Mel dose, impact of renal failure on Mel pharmacokinetics, role of newer antimyeloma agents in preparative regimens, and the timing of auto-HSCT in patients with MM and concomitant renal failure.

In summary, auto-HSCT may be offered to patients with MM and renal failure, with acceptable toxicity and NRM, and a significant improvement in renal function in one-third of these patients. In this analysis, a Mel dose of 200 mg/m2 was not associated with an increase in toxicity or NRM.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Knudsen LM, Hippe E, Hjorth M, Holmberg E, Westin J. Renal function in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma—a demographic study of 1353 patients. The Nordic Myeloma Study Group. Eur J Haematol. 1994;53:207–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1994.tb00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:21–33. doi: 10.4065/78.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith A, Wisloff F, Samson D. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma 2005. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:410–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knudsen LM, Hjorth M, Hippe E. Renal failure in multiple myeloma: reversibility and impact on the prognosis. Nordic Myeloma Study Group. Eur J Haematol. 2000;65:175–181. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2000.90221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blade J, Fernandez-Llama P, Bosch F, et al. Renal failure in multiple myeloma: presenting features and predictors of outcome in 94 patients from a single institution. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1889–1893. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attal M, Harousseau JL, Stoppa AM, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of autologous bone marrow transplantation and chemotherapy in multiple myeloma. Intergroupe Francais du Myelome. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:91–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607113350204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Child JA, Morgan GJ, Davies FE, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem-cell rescue for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1875–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knudsen LM, Nielsen B, Gimsing P, Geisler C. Autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: outcome in patients with renal failure. Eur J Haematol. 2005;75:27–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badros A, Barlogie B, Siegel E, et al. Results of autologous stem cell transplant in multiple myeloma patients with renal failure. Br J Haematol. 2001;114:822–829. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bird JM, Fuge R, Sirohi B, et al. The clinical outcome and toxicity of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with myeloma or amyloid and severe renal impairment: a British Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation study. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:385–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badros A, Barlogie B, Siegel E, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation in elderly multiple myeloma patients over the age of 70 years. Br J Haematol. 2001;114:600–607. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donato ML, Feasel AM, Weber DM, et al. Scleromyxedema: role of high-dose melphalan with autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;107:463–466. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kastritis E, Anagnostopoulos A, Roussou M, et al. Reversibility of renal failure in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients treated with high dose dexamethasone-containing regimens and the impact of novel agents. Haematologica. 2007;92:546–549. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CK, Zangari M, Barlogie B, et al. Dialysis-dependent renal failure in patients with myeloma can be reversed by high-dose myeloablative therapy and autotransplant. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:823–828. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poge U, Gerhardt T, Palmedo H, Klehr HU, Sauerbruch T, Woitas RP. MDRD equations for estimation of GFR in renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1306–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:137–147. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blade J, Samson D, Reece D, et al. Criteria for evaluating disease response and progression in patients with multiple myeloma treated by high-dose therapy and haemopoietic stem cell transplantation. Myeloma Subcommittee of the EBMT. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplant. Br J Haematol. 1998;102:1115–1123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuh A, Dandridge J, Haydon P, Littlewood TJ. Encephalopathy complicating high-dose melphalan. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:1141–1143. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.San Miguel JF, Lahuerta JJ, Garcia-Sanz R, et al. Are myeloma patients with renal failure candidates for autologous stem cell transplantation? Hematol J. 2000;1:28–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qazilbash MH, Saliba RM, Hosing C, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation is safe and feasible in elderly patients with multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:279–283. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qazilbash MH, Saliba RM, Nieto Y, et al. Arsenic trioxide with ascorbic acid and high-dose melphalan: results of a phase II randomized trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:1401–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]