Abstract

Patients and methods

We present a retrospective analysis of 99 consecutive patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas who were older than 65 years at the time of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous progenitor cell transplantation.

Results

Median age at transplant was 68 years (range 65–82). Thirty-six percent of patients had a hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index of >2 at the time of transplantation. The cumulative nonrelapse mortality was 8% [95% confidence interval (CI) 4–17] at 26 months and the 3-year overall survival (OS) was 61% (95% CI 49–71). On multivariate analysis, disease status at transplant and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) > normal were significant predictors for OS (P = 0.002). Comorbidity index of >2 did not impact OS but did predict for higher risk of developing grade 3–5 toxicity (P = 0.006). Eight patients developed secondary myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myelogenous leukemia after transplantation (cumulative incidence 16%).

Conclusions

Patients with relapsed lymphomas who are >65 years of age should be considered transplant candidates, particularly if they have chemosensitive disease and normal LDH levels at the time of transplantation. Patients with comorbidity index of >2 can also undergo transplantation with acceptable outcomes but may be at higher risk for developing toxicity.

Keywords: autologous transplant, elderly, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

introduction

Induction chemotherapy with anthracycline-based regimen can produce complete remission (CR) rates of 50%–70% in patients with newly diagnosed aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL). However, 40%–60% of patients achieving a CR ultimately relapse leading to long-term disease-free survival (DFS) of 40% [1, 2]. In patients with relapsed or refractory disease, the prognosis with chemotherapy alone is generally poor [3].

High-dose therapy (HDT) and autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation (AHPCT) have shown to improve the outcome in relapsed patients who have chemosensitive disease [4, 5]. In the PARMA trial, patients randomly assigned to receive AHPCT had significantly better 5-year overall survival (OS) and DFS than patients receiving continued standard dose chemotherapy [6]. This study involved patients under the age of 55 years, and the role of autologous stem cell transplantation is not well established in older patients.

The majority of lymphoma cases occur in patients older than 65 years. These patients typically have poorer outcomes because of the difficulties encountered during chemotherapy administration, presence of concomitant diseases, diminished organ function, and altered drug metabolism [7]. Only limited information is available on the feasibility and efficacy of HDT and AHPCT in patients >65 years of age [8–17]. We report here results on 99 patients with relapsed or refractory NHL who underwent HDT followed by AHPCT at our institution over 10-year period from June 1996 to March 2006. The aim of this study was to determine the toxicity and nonrelapse mortality (NRM) in this population and to identify prognostic factors if any associated with survival.

patients and methods

We identified all patients who had histologically proven NHL and were older than 65 years of age who received high-dose chemotherapy and AHPCT, treated at our institution from June 1996 to March 2006. Data were collected from an institutional database of blood and marrow transplant recipients and from review of patient records. Patients with uncontrolled medical illness or active infection at the time of planned transplantation were not eligible to receive AHPCT. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients were treated on protocols approved by the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board or as standard of care. The institutional review board approved this retrospective review.

Patient evaluation before transplantation consisted of physical examination, complete blood count, serum chemistry panel, chest radiography, computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, gallium scan or positron emission tomograpy, and bone marrow (BM) aspiration and biopsy. The studies were repeated at 1, 3, and 6 months after transplantation and every 6 months thereafter for 5 years. Hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index (HCT-CI) scores were generated as described by Sorror et al. [18].

collection and processing of progenitor cells

Peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC) were obtained either from steady state or during recovery from chemotherapy depending on the protocols for stem cell collection that were active at the time of study entry. The target progenitor cell dose was ≥4 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg with a minimal acceptable dose of ≥2 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg. Patients who failed to reach that target could undergo BM harvest at the discretion of the treating physician. BM was obtained by multiple aspirations from the right and left iliac crest under general anesthesia. A total of 1000–1500 ml of marrow was obtained for a target total nucleated cell dose of at least 3 × 108 cells/kg. All products were cryopreserved using standard techniques.

preparative regimens and transplantation

The preparative regimen comprised of BEAM (carmustine 300 mg/m2 on day −6, etoposide 200 mg/m2 every 12 h on days −5 to −2, cytarabine 200 mg/m2 every 12 h on days −5 to −2, and melphalan 140 mg/m2 on day −1) with (42%) or without (35%) rituximab in 87 patients [19]. Ten patients who were older than 65 years of age received BEAM (carmustine 300 mg/m2 on day −6, etoposide 100 mg/m2 every 12 h on days −5 to −2, cytarabine 100 mg/m2 every 12 h on days −5 to −2, and melphalan 140 mg/m2 on day −1) with rituximab (10%). Twelve patients received cyclophosphamide/total body irradiation (Cy/TBI) [20] with or without rituximab (10%) or BEAM, rituximab, and ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®) (2%). The source of stem cells was PBPC in 89% (88 of 99) and BM in 8% (8 of 99) of patients. All patients received growth factors starting at day 0 or +1 after transplantation (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor, or both) and continuing till the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was ≥0.5 × 109/l for three consecutive days. All patients were admitted to the hospital for the transplant. They were discharged to outpatient area once they had engrafted and/or were able to take adequate oral intake. All patients received antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal prophylaxis from day of admission through engraftment (antibacterial) or through day +30 after transplantation (antiviral and antifungal). Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis carinii was started after engraftment and continued for a minimum of 6 months after transplantation. First-line therapy for neutropenic fever was a combination of fourth generation cephalosporin and vancomycin. Patients received prophylactic packed red blood cell and platelet transfusions if hemoglobin was <8 g/dl and platelets were <20 × 109/l, respectively. All patients received i.v. fluids for hydration from the start of preparative regimen until they were able to fully recover oral feeding and fluid intake.

response criteria

CR was defined as the disappearance of all clinical evidence of lymphoma for a minimum of 4 weeks with no persisting symptoms related to the disease. When feasible, biopsy of any residual mass was carried out. For a patient to be categorized as a complete responder, any residual masses had to remain unchanged for 6 months or longer. Partial remission (PR) was defined as a >50% decrease in the sum of the products of the two longest diameters of all measurable lesions for at least 4 weeks and nonmeasurable lesions also had to decrease by at least 50%. Additionally, no lesion could increase in size and no new lesion could appear. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as a >25% increase in the sum of the products of the two longest diameters of any measurable lesion or the appearance of a new lesion. Patients who achieved at least a PR with salvage chemotherapy administered before transplantation were considered to have chemosensitive disease and patients who had less than a PR were classified as chemoresistant.

statistical analysis

Primary end points for the study were toxicity [graded as Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse events (CTCAE v 3.0) [21]], NRM, and OS (time from AHPCT until death or last follow-up). Time to treatment failure (TTF) (time from AHPCT until disease relapse, disease progression, death during remission, or last follow-up) was also calculated for the most common subtypes of lymphomas. The methods of Kaplan and Meier [22] were used to estimate the median OS and the median TTF. Cox’s [23] proportional hazards regression model evaluate potential prognostic factors for development of grades 3–5 toxicity and OS in univariate and multivariate analysis. Statistical significance was determined at the 0.05 level. Factors with significance at the 0.05 level in univariate analysis were further evaluated in the multivariate analysis. Statistical significance was determined at the 0.05 level. Analysis was carried out using STATA [24].

results

patient and transplant characteristics

From June 1996 to March 2006, a total of 99 consecutive patients who were older than 65 years of age and underwent HDT and AHPCT for refractory or recurrent NHL at our institution were identified. Patient and transplant characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. There were 30 women and 69 men. The median age at diagnosis of lymphoma was 65 years (range 47–81 years) and median age at transplant was 68 years (range 65–82 years). Fifty-three percent had diffuse large cell lymphoma, and 89% were chemosensitive, achieving at least a partial remission to prior chemotherapy. The median number of prior chemotherapy regimens was two (range 1–8). At the time of transplant, 30% of patients had stage III or IV disease and 64% of patients had a HCT-CI of ≤2.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| N = 99 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years), median (range) | 65 (47–81) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 69 | 70 |

| Female | 30 | 30 |

| Age at transplant (years), median (range) | 68 (65–82) | |

| Interval from diagnosis to transplant (years), median (range) | 2.2 (0.5–18) | |

| Prior chemotherapy regimens, median (range) | 2 (1–8) | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase > normal | 24 | 24 |

| IPI at study entry, median (range) | 1 (0–4) | |

| IPI > 1 | 43 | 44 |

| Ann arbor stage | ||

| 0–II | 69 | 70 |

| III–IV | 30 | 30 |

| Zubrod performance status score < 2 | 98 | 99 |

| Comorbidity index | ||

| ≤2 | 63 | 64 |

| >2 | 36 | 36 |

| Histology at diagnosis | ||

| Diffuse large cell lymphoma | 53 | 53.5 |

| Diffuse mixed cell lymphoma | 2 | 2 |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 15 | 15 |

| Follicular grades 1–3 lymphoma | 11 | 11 |

| Composite/discordant | 8 | 8 |

| Peripheral T-cell lymphoma | 4 | 4 |

| Other large-cell lymphoma | 5 | 5 |

| Small noncleaved cell—Burkitt like | 1 | 1 |

| Disease status at transplant | ||

| CR/CRu | 44 | 45 |

| PR | 44 | 44 |

| SD/PD | 7/4 | 11 |

IPI, International Prognostic Index; CR/CRu, complete remission/complete remission unconfirmed; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease.

Table 2.

Transplant characteristics

| N = 99 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Conditioning regimen | ||

| BEAM | 35 | 35 |

| BEAM/rituximab | 52 | 53 |

| BEAM/rituximab + Zevalin | 2 | 2 |

| Cy/TBI ± rituximab | 10 | 10 |

| Rituximab/no rituximab | 57/42 | 58/42 |

| Source of stem cells | ||

| PBPC | 88 | 89 |

| BM | 8 | 8 |

| PBPC plus BM | 3 | 3 |

| CD34 infused, median (range) | ||

| ≤5 × 106/kg | 61 | 3.5 (0.08–4.92) |

| >5 × 106/kg | 37 | 7.4 (5.03–32.2) |

| Length of hospital stay in days, median (range) | 23 (6–85) | |

| Days to ANC ≥500/mm3 (n = 99) | 10 (7–47) | |

| Days to PLT ≥20 000/mm3 (n = 89) | 13 (6–375) | |

| Number of PRBC units infused, median (range) | 4 (0–50) | |

| Number of PLT transfusions required, median (range) | 4 (0–35) | |

| Readmissions in first 100 days after AHPCT | 38 | |

BEAM, BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan; Cy/TBI, cyclophosphamide/total body irradiation; PBPC, peripheral blood progenitor cells; BM, bone marrow; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; PLT, platelets; AHPCT, autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation.

transplant and engraftment

The median CD34+ cell dose infused/kg was 4.4 × 106 (0.08–32.2). All patients engrafted. Median time to reach an ANC of ≥0.5 × 109/l was 10 days (range 7–47). Ten patients never achieved a platelet count of 20 × 109/l. For the remaining 89 patients, the median time to reach platelet count of ≥20 × 109/l was 13 days (range 6–375). Median number of packed red blood cell units transfused were four (range 0–50) and the median number of platelet transfusions required was four (range 0–35).

toxicity

Median length of hospital stay was 23 days (range 6–85) for AHPCT with 38% of patients requiring readmission within the first 100 days. A total of 58 patients developed infectious complications after transplantation. The most commonly isolated organisms were Coagulase-negative staplylococcus (13 patients), Clostridium difficile colitis (6 patients), Candida spp. (7 patients), Cytomegalovirus reactivation (6 patients), and Cytomegalovirus infection (1 patient). There were 15 episodes of fever with no organism identified on cultures (pneumonia, sinusitis, and cellulitis). The most common toxicity was gastrointestinal (mucositis, stomatitis, and diarrhea) in 16% of patients. A total of 36 patients experienced grades 3–5 toxicity (CTCAE v 3.0) Table 3.

Table 3.

Regimen related toxicity grades 3–5 (CTCAE v 3.0)

| Age years (n) | 65–69 (58 patients) | 70–75 (34 patients) | >75 (8 patients) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity grade | 3/4/5 | 3/4/5 | 3/4/5 |

| Pulmonary (pneumonitis/fibrosis) | 1/1/0 | 0/0/1 | 0/0/1 |

| GI (diarrhea) | 6/0/0 | 2/0/0 | 0/0/0 |

| GI (mucositis/stomatitis) | 6/0/0 | 0/0/0 | 1/0/1 |

| GI (nausea) | 0/0/0 | 0/0/0 | 1/0/0 |

| Neurologic (confusion) | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | 0/0/0 |

| GU (inc creatinine) | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 |

| Hepatic (inc ALT/AST) | 1/1/0 | 0/0/0 | 0/0/0 |

| Cardiovascular | 4/0/0 | 1/0/0 | 2/2/0 |

| Allergy (BCNU) | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | 0/0/0 |

| Skin rash | 1/0/0 | 1/0/0 | 0/0/0 |

| Fatigue/bone pain | 2/0/0 | 0/0/0 | 1/0/0 |

| Total toxicities | 24/2/0 | 7/0/1 | 6/2/2 |

| Total patients | 24 | 8 | 4 |

GI, gastrointestinal; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

nonrelapse mortality

At the time of this report, a total of 39 patients have died. Cumulative NRM was 8% [95% confidence interval (CI) 4–17] at 26 months and 12% (95% CI 6–22) at 36 months. Four patients died before day 100, three due to transplant-related causes and one due to disease progression. The most common cause of death was disease relapse/progression in 21 (54%) patients, followed by secondary myelodysplasia/acute myelogenous leukemia in eight patients (20%). Causes of death are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Causes of death

| Cause | Number of patients (%), N = 39 |

|---|---|

| Disease relapse | 21 (54) |

| Infections | 2 (5) |

| Organ failure | 3 (8) |

| Cardiac failure | 1 |

| Renal failure | 1 |

| Pulmonary | 1 |

| Secondary malignancy | 8 (20) |

| Other/unknown | 5 (13) |

response to AHPCT and OS

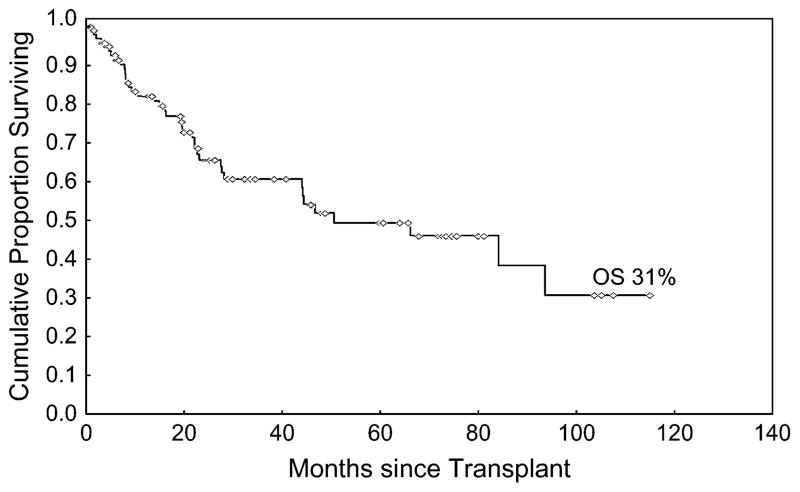

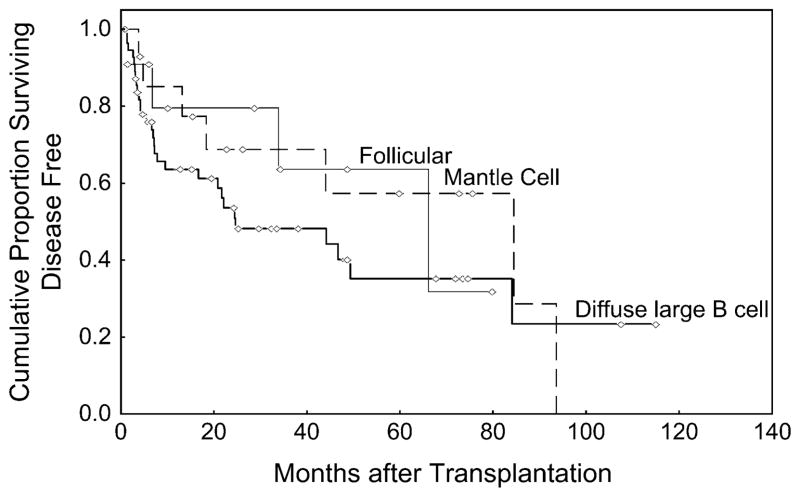

A total of 83 (83%) patients achieved a CR after transplantation. At the time of this analysis, the median follow time among survivors is 26 months (range 1–115). The 3-year OS for the entire cohort was 61% (95% CI 49–71) (Figure 1). The TTF at 3 years was 48% (95% CI 33–62), 69% (95% CI 36–87), and 64% (95% CI 22–87) for diffuse large B cell, mantle cell, and follicular lymphomas, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Overall survival form the time of transplantation.

Figure 2.

Time to treatment failure.

prognostic factors

In the univariate analysis, International Prognostic Index (IPI) > 1, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) > upper limit of normal, having received BM grafts, and having stable disease (SD)/PD at the time of transplantation were associated with a significantly worse OS (P < 0.05). On multivariate analysis, only LDH > upper limit of normal [HR 3.3 (95% CI 1.6–6.8); P = 0.002] and having SD/PD [HR 4.3 (95% CI 1.7–10.9); P = 0.002] remained significant factors for survival. Of the eight patients who received BM grafts, four also had LDH values > normal and due to the small number of patients we were unable to adjust for graft type in the multivariate analysis for OS. Age, gender, histology, number of prior chemotherapy regimens, rituximab in the preparative regimen, time from diagnosis to AHPCT, HCT-CI, and stem cell dose infused were not significant predictors of OS (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for overall survival

| n | Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazards ratio | 95% CI | P value | Hazards ratio | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Age > 68 years | 48 | 1.2 | 0.6–2.4 | 0.7 | |||

| Prior response | |||||||

| CR/CRu | 44 | ||||||

| PR | 44 | 0.9 | 0.4–2.1 | 0.8 | |||

| SD/PD | 11 | 4.3 | 1.7–10.9 | 0.002 | 4.3 | 1.7–10.9 | 0.002 |

| International prognostic index | |||||||

| >1 | 43 | 2.4 | 1.2–4.9 | 0.02 | |||

| ≤1 | 55 | ||||||

| Lactate dehydrogenase levels | |||||||

| >normal | 24 | 3.3 | 1.6–6.9 | 0.001 | 3.3 | 1.6–6.8 | 0.002 |

| ≤normal | 74 | ||||||

| Stage at transplant | |||||||

| 0–II | 69 | ||||||

| III–IV | 30 | 1.4 | 0.7–2.9 | 0.4 | |||

| Time from diagnosis to transplant (years) | |||||||

| >2 | 55 | 1.03 | 0.5–2.1 | 0.9 | |||

| ≤2 | 44 | ||||||

| HCT-CI | |||||||

| ≤2 | 63 | 0.7 | 0.3–1.5 | 0.4 | |||

| >2 | 36 | ||||||

| Number of prior chemotherapy regimens | |||||||

| >2 | 38 | 1.45 | 0.7–2.97 | 0.3 | |||

| ≤2 | 61 | ||||||

| CD34 infused/kg | |||||||

| ≤5 × 106 | 61 | ||||||

| >5 × 106 | 37 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.2 | 0.1 | |||

| Preparative regimen | |||||||

| BEAM versus all other | 1.9 | 0.9–3.9 | 0.07 | ||||

CI, confidence interval; CR/CRu, complete remission, complete remission unconfirmed; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index; BEAM, BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan.

Having a HCT-CI of ≤2 at the time of transplantation predicted for a lower incidence of grades 3–5 toxicity (HR 0.3, P = 0.006). Other factors that impacted on the development of grades 3–5 toxicity included receiving Cy/TBI (P = 0.001) as the preparative regimen and age <68 years (P < 0.001). IPI score, disease status and stage at the time of AHPCT, LDH, number of prior chemotherapy regimens, time from diagnosis to AHPCT, source of stem cells, rituximab in the preparative regimen, and stem cell dose infused were not significant predictors for developing grades 3–5 toxicity.

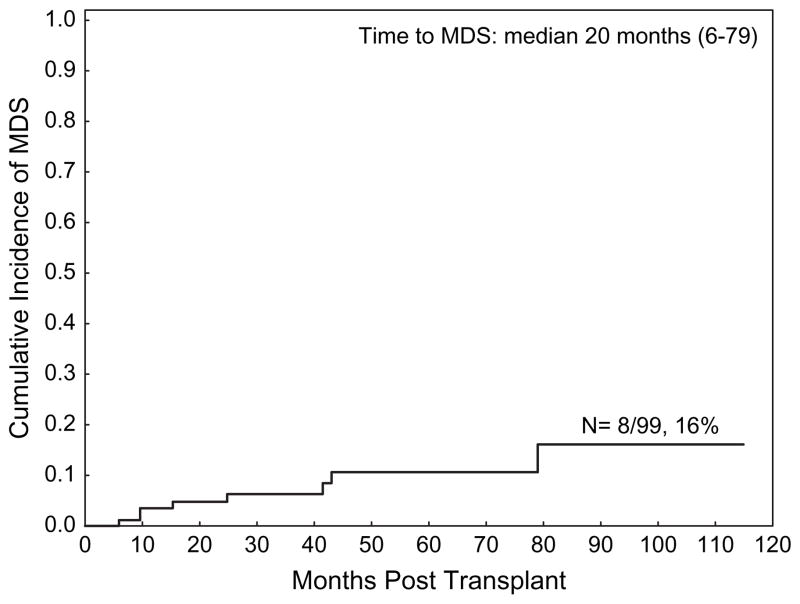

secondary myelodysplasia/acute leukemia

A total of eight patients developed secondary myelodysplasia/acute leukemia after transplantation at a median of 20 months after AHPCT (range 6–79 months). The cumulative incidence of developing secondary myelodysplasia/acute leukemia was 16% (95% CI 7–35) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of secondary myelodysplasia/leukemia.

discussion

This retrospective analysis is the largest study published to date that examines the outcome of autologous stem cell transplantation in patients older than 65 years of age. Until recently, elderly patients were not considered to be appropriate candidates for clinical trials of HDT and AHPCT because of concerns regarding the toxicity of high-dose chemotherapy in older, frailer patients. On the basis of the PARMA study [6] and others, HDT followed by AHPCT is currently considered to be the standard of care for young patients with relapsed chemosensitive aggressive NHL. The upper age limit for autologous transplantation in the PARMA study was only 55 years, the use of autologous stem cell transplantation in older patients is not well established.

No randomized studies have been carried out in older patients. Several small studies have indicated that autologous transplants can be carried out in older patients with hematologic malignancies [8–17], but only limited information is available on the feasibility and efficacy of HDT and AHPCT in patients >65 years of age.

The median age of the patients at the time of AHPCT in these studies ranged from 62 to 67 years. The study where the median age was 67 years, however, included only 10 patients [12]. The 100-day transplant-related mortality (TRM) ranged from 0% to 11%, which is comparable to our study in which the 100-day mortality was 4% and the cumulative NRM at 26 months was 8%. The mortality is comparable to the studies in patients <60 years of age. For example, early TRM was 3% in NHL patients <60 years of age who received AHPCT in Finland (1990–2003) [17] and 0% in a single institution study [19].

In a recent study by Jantunen et al., a total of 88 NHL patients >60 years old received AHPCT in six Finnish transplant centers between 1994 and 2004. Median age in their study was 63 years (range 60–70 years), and only 17 patients were >65 years. The median time to engraftment of neutrophils >0.5 × 109/l and platelets >20 × 109/l were 10 and 14 days, respectively. The 100-day TRM was 11%. With a median follow-up of 21 months for all patients, 45 patients (51%) were alive. The authors concluded that AHPCT is feasible in selected elderly patients with NHL but in their study the early TRM seemed to be higher than in younger patients [17]. Although the results are similar to those observed in our study, the median age at the time of transplantation was higher in our study (68 versus 63 years).

In the present study, disease status and LDH levels at the time of transplantation were the only factor that impacted OS on multivariate analysis. The 3-year OS for the entire cohort was 61% (95% CI 49–71) (Figure 1). The 3-year TTF was 48% (95% CI 33–62), 69% (95% CI 36–87), and 64% (95% CI 22–87) for diffuse large B cell, mantle cell, and follicular lymphomas, respectively (Figure 2). In a parallel study of AHPCT in patients who were younger than 65 years of age at the time of their transplantation for relapsed chemosensitive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, the OS and DFS at 2 years were 80% and 67%, respectively [19].

Eligibility criteria for transplantation typically include consideration for comorbidities. HCT-CI of >2 at the time of transplantation did not predict for higher NRM. Patients with higher scores, however, were at significantly higher risk for developing grades 3–5 toxicity after transplantation. Although this scoring system was originally described for patients undergoing allogeneic transplants, it has been applied to elderly patients undergoing chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia [25, 26] and also appears useful for evaluation of autologous stem cell transplantation.

The cumulative incidence of secondary leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome was 16% in this study. This appears somewhat higher than in many studies of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous transplantation in younger patients. This may be a reflection of the rising incidence of myelodysplasia with age [26]. All eight patients who developed secondary myelodysplasia/leukemia were >65 years of age at the time of their transplantation. There was also a trend toward increasing incidence in patients who had received >3 chemotherapy regimens before transplantation. However, because of the small number of cases none of these reached statistical significance on univariate analysis.

One of the limitations of this study and others is the retrospective nature of this analysis. Thus, we are not able to determine how many elderly patients were not considered candidates for AHPCT because of age, Zubrod Performance status score, failure to mobilize adequate stem cells, or other, more severe comorbidities.

In conclusion, this retrospective analysis indicates that elderly patients can undergo high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation with acceptable NRM. Patients with relapsed NHL who achieve a CR/PR to salvage chemotherapy and have normal LDH have the best prognosis. Although, the numbers are small in our study, HCT-CI of ≥2 had a greater risk for grade 3 or higher toxicity but not NRM. Patients over the age of 65 years should be considered candidates for HDT and stem cell transplantation and should also be included in clinical trials to optimize the management of lymphomas.

References

- 1.Armitage J. Treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1023–1030. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304083281409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher RI, Gaynor ER, Dahlberg S, Oken MM, et al. Comparison of a standard regimen (CHOP) with three intensive chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1002–1006. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304083281404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armitage JO, Vose JM, Bierman PJ, et al. Salvage therapy for patients with lymphoma. Semin Oncol. 1994;21:82–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vose JM, Rizzo DJ, Tao-Wu J, et al. Autologous transplantation for diffuse aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma in first relapse or second remission. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004;10:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philip T, Armitage JO, Spitzer G, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation after failure of conventional chemotherapy in adults with intermediate-grade or high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1493–1498. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706113162401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1540–1545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thieblemont C, Coiffier B. Lymphoma in older patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1916–1923. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olivieri A, Capelli D, Montanari M, et al. Very low toxicity and good quality of life in 48 elderly patients autotransplanted for hematological malignancies: a single center experience. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:1189–1195. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stamatoullas A, Fruchart C, Khalfallah S, et al. Peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for relapsed or refractory aggressive lymphoma in patients over 60 years of age. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:31–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreau P, Milpied N, Voillat L, et al. Peripheral blood stem cell transplantation as front-line therapy in patients aged 61 to 65 years: a pilot study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:1193–1196. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gopal AK, Gooley TA, Golden JB, et al. Efficacy of high-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in adults 60 years of age and older. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:593–599. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zallio F, Cuttica A, Caracciolo D, et al. Feasibility of peripheral blood progenitor cell mobilization and harvest to support chemotherapy intensification in elderly patients with poor prognosis: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:448–453. doi: 10.1007/s00277-002-0492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bitran JD, Klein L, Link D, et al. High-dose myeloablative therapy and autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation for elderly patients (greater than 65 years of age) with relapsed large cell lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:383–388. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(03)00099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buadi FK, Micallef IN, Ansell SM, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for older patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:1017–1022. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leger CS, Bredeson C, Kearns B, et al. Autologous blood and marrow transplantation in patients 60 years and older. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2000;6:204–210. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(00)70044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villela L, Sureda A, Canals C, et al. Low transplant related mortality in older patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2003;88:300–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jantunen E, Itala M, Juvonen E, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation in elderly (>60 years) patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a nation-wide analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:367–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106:2912–2919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khouri IF, Saliba RM, Hosing C, et al. Concurrent administration of high-dose rituximab before and after autologous stem-cell transplantation for relapsed aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2240–2247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khouri IF, Romaguera J, Kantarjian H, et al. Hyper-CVAD and high-dose methotrexate/cytarabine followed by stem-cell transplantation: an active regimen for aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3803–3809. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.12.3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, et al. CTCAE v3. 0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:176–181. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilcoxon F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biometrics. 1945;1:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 24.StataCorp: Stata Corporation. StataCorp: Stata Statistical Software. Release 7.0. Stata Corporation; College Station, TX: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giles FJ, Borthakur G, Ravandi F, et al. The haematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index score is predictive of early death and survival in patients over 60 years of age receiving induction therapy for acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:624–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Etienne A, Esterni B, Charbonnier A, et al. Comorbidity is an independent predictor of complete remission in elderly patients receiving induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2007;109:1376–1383. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]