Abstract

Background

We report the main results, among adults, of a cluster-randomised-trial of Well London, a community-engagement programme promoting healthy eating, physical activity and mental well-being in deprived neighbourhoods. The hypothesis was that benefits would be neighbourhood-wide, and not restricted to intervention participants. The trial was part of a multicomponent process/outcome evaluation which included non-experimental components (self-reported behaviour change amongst participants, case studies and evaluations of individual projects) which suggested health, well-being and social benefits to participants.

Methods

Twenty matched pairs of neighbourhoods in London were randomised to intervention/control condition. Primary outcomes (five portions fruit/vegetables/day; 5×30 m of moderate intensity physical activity/week, abnormal General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-12 score and Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) score) were measured by postintervention questionnaire survey, among 3986 adults in a random sample of households across neighbourhoods.

Results

There was no evidence of impact on primary outcomes: healthy eating (relative risk [RR] 1.04, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.17); physical activity (RR:1.01, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.16); abnormal GHQ12 (RR:1.15, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.61); WEMWBS (mean difference [MD]: −1.52, 95% CI −3.93 to 0.88). There was evidence of impact on some secondary outcomes: reducing unhealthy eating-score (MD: −0.14, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.27) and increased perception that people in the neighbourhood pulled together (RR: 1.92, 95% CI 1.12 to 3.29).

Conclusions

The trial findings do not provide evidence supporting the conclusion of non-experimental components of the evaluation that intervention improved health behaviours, well-being and social outcomes. Low participation rates and population churn likely compromised any impact of the intervention. Imprecise estimation of outcomes and sampling bias may also have influenced findings. There is a need for greater investment in refining such programmes before implementation; new methods to understand, longitudinally different pathways residents take through such interventions and their outcomes, and new theories of change that apply to each pathway.

Keywords: RANDOMISED TRIALS, DEPRIVATION, DIET, EXERCISE, HEALTH PROMOTION

Background

The persistence of stark health inequalities linked to levels of social disadvantage in high-income countries is well recognised.1 2 Many structural drivers, such as employment, education and income distribution lie in the field of macroeconomic and social policy.3 However, interventions which seek to act on the local social context of disadvantage have become more widespread,4–10 driven by the neighbourhood renewal policies popular since the late 1990s.11 12 This has paralleled a move in broader public service delivery from using needs-assessments to design and target professionally delivered services, towards highlighting and harnessing the skills, knowledge and resources of individuals and communities in coproducing and delivering services.13 14 The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has produced guidance on the use of community engagement for delivering health services and preventive interventions.13 This, together with a new systematic review, suggest that coproduced interventions impact health beyond the direct effects of their health content, through: (1) enhancing social support networks15 which provide a buffer against macrolevel structural drivers of poor health16 17 and (2) increasing the control people have over their local environments.18–22

Despite this increase in coproduction interventions in public health, evidence for their effectiveness remains limited, and there have been repeated calls to improve the quantity and quality of evaluation.15 21–23 However, such interventions are not usually delivered in ways that are amenable to the use of randomised experimental designs for assessing effectiveness, and some have questioned whether trials are appropriate to these interventions.24–27 In this paper, we present findings, among adults, from a cluster-randomised trial (CRT) of a community engagement intervention to promote health and well-being, delivered in deprived neighbourhoods in London: the Well London Programme. The trial was conducted as part of a wider evaluation which included collecting information on participation levels, and self-reported behaviour change among participants, as well as interviews with residents and local stakeholders and independent evaluations of individual projects. Findings of the wider non-experimental evaluation suggested health and other benefits from participation, as well as improved social cohesion, interagency collaboration and relationships between communities, decision makers and service providers.28

The CRT sought to determine the effectiveness of the Well London programme in improving healthy eating, physical activity and mental well-being in adults and adolescents, and enhancing the social characteristics, structure and function of the target communities, which are hypothesised to underpin changes in well-being and health behaviour outcomes.29 We sought evidence of neighbourhood-wide impact on residents, irrespective of their levels of engagement/exposure with the programme. In a companion paper in this edition, we explore levels of exposure to the programme within intervention neighbourhoods and association of these with outcomes30 The results of the accompanying qualitative study have been reported seperately.31 Outcomes among adolescents are being measured through ongoing school-based surveys, the results of which will be reported later in 2014.

Methods

The intervention

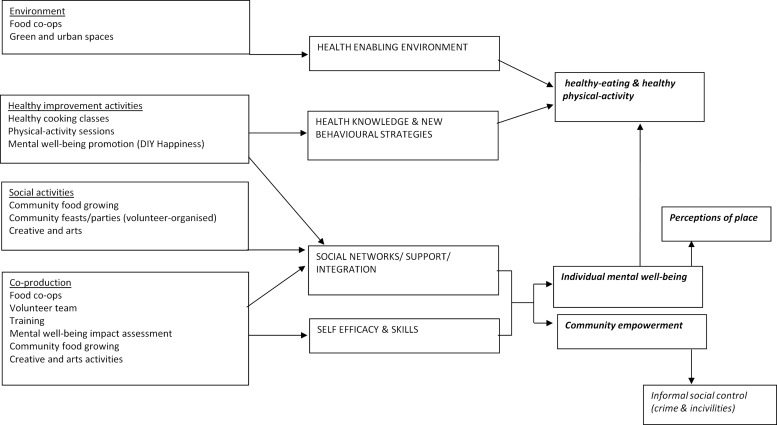

Well London is a multicomponent, community engagement programme for improving mental well-being, healthy eating and healthy physical activity in multiply deprived communities (See http://data.gov.uk/dataset/index-of-multiple-deprivation).32 33 Phase 1 of the programme comprised 14 interlinked projects developed and delivered in 20 deprived neighbourhoods in London, using a coproduction approach. Some projects focussed on the main outcomes, using traditional health behaviour change activities, while others sought to improve the local environment (eg, green spaces), provide cultural activities, and improve employment and training opportunities. A core group of volunteers (modelled on the UK National Health Service Health Trainers34-Well-London Delivery-Teams) in each neighbourhood, supported residents to participate in Well London, access services and improve health behaviours. All projects were locally adapted to community preferences, in line with current best practice.27 35 The overarching theory of change model is summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theory of change for the Well London programme.

The funding for the intervention was obtained on the basis of the following impact targets: a 50% increase in the proportion of adults (base estimate 27%) who eat five or more pieces of fruit and vegetables a day; a 70% increase in the proportion of adults taking 30 min of moderate-level physical activity five times a week (base estimate 18%); and a 30% increase in the proportion of adults achieving key thresholds on mental health and well-being indices. Well London Phase-1 was supported by the Big Lottery Well-being Fund and delivered between October 2007 and March 2011. This period is the subject of the evaluation reported here. Well London Phase-2 is being delivered in a further nine neighbourhoods in nine London boroughs. Further information about individual projects is provided on the Well London website33 and in online supplementary file 1. A summary of the timing and number of projects delivered in each intervention neighbourhood is provided in online supplementary file 2.

Trial design

A CRT design was selected because delivery was at neighbourhood level and to capture indirect effects of the intervention. The unit of intervention delivery and analysis for the CRT was the UK census lower-super-output-area (LSOA). The CRT included 20 intervention and 20 control neighbourhoods with high levels of deprivation, matched by borough. Control neighbourhoods received no additional intervention beyond routine public health practice. Outcomes were measured by household survey among adults before (baseline) and after (follow-up) intervention delivery. The trial registration is: ISRCTN68175121. Full details of the trial design and the analysis plan are published in the baseline survey paper30 and appendices and the protocol paper.32

Study objectives

To assess the effect of Well London for improving healthy eating, physical activity and mental well-being in communities receiving the intervention (not just in individuals who directly engaged with the programme).

To assess the effect of Well London on the social characteristics of communities and physical characteristics of neighbourhoods.

To assess the above effects in population subgroups, defined by age, gender, ethnicity, employment status and educational attainment.

Outcomes

We report intervention effects on primary and secondary health outcomes related to healthy eating, physical activity and mental well-being and a range of social outcomes as published previously36 and summarised in online supplementary files 3 and 4. Primary outcomes were: eating five portions of fruit/vegetables daily, taking 5×30 min moderate-intensity physical activity per week, abnormal/borderline GHQ-12 score and Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale score. All outcomes, except incivilities, were measured at the individual level through repeat cross-sectional adult surveys. Incivilities were measured by neighbourhood environmental audit. All outcomes were analysed at the cluster level.

Data collection

Household adult surveys

A cross-sectional household survey was conducted at baseline and follow-up. There was no longitudinal follow-up of individuals. Households were randomly selected in each intervention and control neighbourhood, using the Post Office Address File as a sampling frame. At responding addresses, interviews were sought with every eligible household member aged 16 years and older, and interviews were conducted where consent was given. Paper questionnaires were used at baseline and computer-assisted personal interviewing at follow-up. The target sample for each neighbourhood was 100 interviews at baseline and 100 at follow-up. The domains covered in the follow-up questionnaire (available on request) are detailed in online supplementary file 5.

Environmental audit

An environmental audit was used to capture data on characteristics of the neighbourhoods. Details of the characteristics observed are provided in online supplementary file 4 and in the baseline survey paper.36 The audit tool is available on request. Each neighbourhood was split into segments, and the audit tool applied to each segment. Composite neighbourhood-level indicators were created from the multiple segments by summing or averaging the segment-level ratings.

Sample size

The original sample size/power calculations (based on the impact targets presented in the description of the intervention above) are published in a trial design paper.32 Updated sample size/power calculations based on the between-cluster coefficients of variation estimated from the baseline survey are published in a further paper.36 These show that the trial was powered at 80% to detect a 22% increase in the prevalence of eating five-a-day and a 19% increase in the prevalence for doing 5×30 min of activity per week. The mental health outcomes were not measured at baseline.

Randomisation

The following process was used for selection of the neighbourhoods (LSOAs):

All 4765 LSOAs in London were ranked by the English Indices of Multiple Deprivation.37 38

The 20 London boroughs containing at least 4 LSOAs falling among the most deprived 11% in London were identified, and the four most deprived listed for each borough.

Local authorities and health professionals selected two non-contiguous LSOAs from the four identified in their borough.

These were randomly allocated, one to intervention, the other to control condition.

Statistical analysis

Overview

Effect-estimates were calculated by comparing intervention and control neighbourhoods at follow-up. The data were analysed according to the methods described by Hayes and Moulton for pair-matched cluster randomised trials.39 Crude and adjusted effect-estimates were calculated for all health and social outcomes.36

Means and proportions for the outcomes and sociodemographic characteristics are presented by trial arm with CIs based on robust SEs to account for clustering. All analyses were conducted in Stata V.11.2.40

Crude effect-estimates

We present differences in means for continuous outcomes and ratios of proportions for binary outcomes, with 95% CIs. The paired t test was used to test for differences between control and intervention neighbourhoods (mean differences for continuous and log (risk ratios) for binary outcomes) and corresponding 95% CIs were calculated using the t distribution.39

Adjusted effect-estimates

Estimates were adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment, employment status and neighbourhood-level summaries of the outcomes collected in the baseline survey using the two-stage method described by Hayes and Moulton,39 and summarised in online supplementary file 6.

Subgroup analyses

The adjusted effects on the primary health outcomes were estimated within subgroups of age, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment and employment status. Linear regression was used to test for heterogeneous effect of the intervention across subgroups (see online supplementary file 6).

Missing data

All analyses were conducted using complete cases because the levels of missing data in the outcomes were low (see online supplementary file 7). For all outcomes, complete cases were defined as survey respondents who were not missing the outcome variable or any sociodemographic variables used for adjustment. Sample size, therefore, differs between outcomes because of variability in completeness of outcome variables. For tables 2 and 3 the sample size for the estimates shown ranged from 1825 to 1876 for control neighbourhoods and from 1792 to 1886 for intervention neighbourhoods.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary health outcomes and intervention effect-estimates

|

Summary statistics Mean of continuous and prevalence of binary outcomes* |

Effect-estimates Risk ratio for binary outcomes, mean difference for continuous outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (95% CI) | Intervention (95% CI) | Unadjusted (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted† (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Primary health outcomes | ||||||

| Healthy eating—meeting five-a-day (fruit and vegetable portions) % | 53.4 (47.6 to 59.3) | 55.6 (50.3 to 60.9) | 1.02 (0.89 to 1.17) | 0.7 | 1.04 (0.93 to 1.17) | 0.5 |

| Physical activity—meeting 5×30 min moderate intensity activity per week, % | 66.5 (59.0 to 74.0) | 68.4 (63.5 to 73.2) | 1.04 (0.89 to 1.22) | 0.6 | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.16) | 0.9 |

| Mental well-being | ||||||

| Abnormal/borderline GHQ12 score % | 6.1 (4.7 to 7.6) | 7.2 (5.5 to 8.9) | 1.17 (0.84 to 1.63) | 0.3 | 1.15 (0.82 to 1.61) | 0.9 |

| Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale; mean score‡ | 60.1 (58.3 to 61.9) | 58.7 (56.8 to 60.5) | −1.59 (−4.10 to 0.91) | 0.2 | −1.52 (−3.93 to 0.88) | 0.2 |

| Secondary health outcomes | ||||||

| Unhealthy eating—mean score§ | 2.7 (2.6 to 2.8) | 2.5 (2.5 to 2.6) | −0.12 (−0.27 to 0.02) | 0.08 | −0.14 (−0.27 to −0.02) | 0.03 |

| Healthy eating—number of portions of fruit and vegetables per day—mean | 5.2 (5.0 to 5.5) | 5.3 (5.0 to 5.6) | 0.13 (−0.27 to 0.53) | 0.5 | 0.11 (−0.23 to 0.45) | 0.5 |

| Physical activity | ||||||

| Meeting 7×60 min moderate intensity activity per week % | 30.0 (21.6 to 38.5) | 31.6 (24.6 to 38.6) | 1.10 (0.62 to 1.94) | 0.7 | 1.02 (0.65 to 1.62) | 0.9 |

| Doing 150 min of moderate intensity activity per week % | 75.4 (68.0 to 82.9) | 77.0 (72.4 to 81.5) | 1.03 (0.89 to 1.20) | 0.6 | 1.00 (0.88 to 1.14) | 1.0 |

| Mean MET-minutes per week—mean | 2626 (1978 to 3279) | 2659 (2085 to 3233) | 4.2 (−778 to 787) | 1.0 | −113 (−847 to 621) | 0.7 |

| Mental well-being– mean GHQ 12 score¶ | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.8) | −0.003 (−0.13 to 0.12) | 1.0 | −0.01 (−0.15 to 0.12) | 0.4 |

*Overall mean or prevalence pooled over clusters (CI adjusted for clustering).

†Adjustment for age, gender, ethnicity, education, employment, appropriate baseline values.

‡Higher score indicates better mental well-being.

§Higher score indicates more unhealthy food consumption.

¶Higher score indicates poorer mental health.

GHQ, General Health Questionnaire.

Table 3.

Social outcomes and intervention effect-estimates

|

Summary statistics Mean of continuous and prevalence of binary outcomes* |

Effect-estimates Rate ratio for binary outcomes, mean difference for continuous outcomes |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (95% CI) | Intervention (95% CI) | Unadjusted (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted† (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Social networks; mean score possible range 0–112)‡ | 76.5 (70.6 to 82.4) | 78.2 (70.7 to 85.7) | 1.20 (−6.00 to 8.41) | 0.7 | 0.64 (−6.47 to 7.76) | 0.9 |

| Social support; mean score (possible range 0–6)§ | 3.2 (2.6 to 3.9) | 3.2 (2.4 to 4.0) | −0.03 (−1.06 to 1.00) | 1.0 | −0.04 (−1.02 to 0.94) | 0.9 |

| Social integration % agree | ||||||

| Some or most people in neighbourhood can be trusted | 39.3 (27.9 to 50.6) | 31.2 (24.0 to 38.4) | 0.85 (0.46 to 1.6) | 0.6 | 0.87 (0.48 to 1.56) | 0.6 |

| People from different backgrounds in the neighbourhood get on | 5.4 (3.4 to 7.5) | 9.2 (6.2 to 12.2) | 1.38 (0.81 to 2.33) | 0.2 | 1.30 (0.80 to 2.13) | 0.3 |

| Racial harassment is a problem in the neighbourhood | 13.7 (7.4 to 20.0) | 10.9 (4.6 to 17.1) | 0.62 (028 to 1.37) | 0.3 | 0.62 (0.29 to 1.31) | 0.3 |

| Collective efficacy % agree | ||||||

| People in the neighbourhood pull together to improve it | 13.0 (8.9 to 17.1) | 28.7 (18.2 to 39.2) | 2.0 (1.10 to 3.60) | 0.03 | 1.92 (1.12 to 3.29) | 0.02 |

| People in the neighbourhood help each other and do things together | 19.8 (12.5 to 27.2) | 15.4 (10.8 to 19.9) | 0.71 (0.38 to 1.32) | 0.3 | 0.71 (0.38 to 1.30) | 0.3 |

| Taken any action to solve problems in the local area in past 12 months | 39.7 (26.8 to 52.6) | 26.2 (17.7 to 34.8) | 0.69 (0.38 to 1.24) | 0.2 | 0.70 (0.42 to 1.19) | 0.2 |

| Volunteering; any in last 12 m % | 20.5 (15.8 to 25.2) | 18.7 (13.4 to 24.0) | 0.94 (0.60 to 1.47) | 0.8 | 0.95 (0.64 to 1.41) | 0.8 |

| Antisocial behaviour—resident perceptions—mean score (possible range 0–6)¶ | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.3) | 1.8 (1.3 to 2.2) | 0.05 (−0.46 to 0.57) | 0.8 | 0.05 (−0.43 to 0.53) | 0.8 |

| Antisocial behaviours/incivilities—environmental audit—mean score, (possible range 0–100)** | 8.8 (7.3 to 10.3) | 8.2 (6.8 to 9.7) | −0.5 (−1.9 to 0.9) | 0.4 | −0.6 (−1.9 to 0.8) | 0.4 |

| Fear of crime | ||||||

| Feel safe in the neighbourhood (day) % | 96.2 (94.4 to 97.9) | 95.4 (93.7 to 97.0) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) | 0.3 | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) | 0.3 |

| Feel safe in the neighbourhood at night % | 58.1 (48.5 to 67.8) | 57.8 (52.1 to 63.5) | 1.03 (0.81 to 1.32) | 0.8 | 1.02 (0.82 to 1.26) | 0.9 |

*Overall mean or prevalence pooled over clusters (CI adjusted for clustering).

†Adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, education and employment status except incivilities which are adjusted for baseline values only.

‡Higher score=greater social connectedness.

§Higher score=greater social support.

¶Higher score=higher levels of perceived incivilities (survey respondents).

**Higher score indicates higher levels of recorded incivilities (environmental audit).

Resident turnover and contamination

Respondents were asked how long they had lived in the neighbourhood. The following indicators of resident turnover were constructed in relation to key events in the delivery of the Well London programme:

The proportion arriving since Well London started.

The proportion arriving since the beginning of the final year of Well London.

The proportion arriving since Well London ended.

Effect-estimates were recalculated excluding respondents arriving into the CRT neighbourhoods after each of these events, to check whether duration of exposure to the intervention affected its impact.

The contamination rate in the control areas was calculated as the proportion of all survey respondents reporting having taken part in Well London.

Survey response rate

The response rate for the survey was calculated at the household level according to the approach used for the Health Survey for England41 as the percentage of all households visited where at least one adult was interviewed. Addresses that were non-residential or unoccupied were excluded from the denominator for the response rate. The household refusal rate was calculated as the proportion of visited households where contact was made but interviews refused.

Results

Participant flow

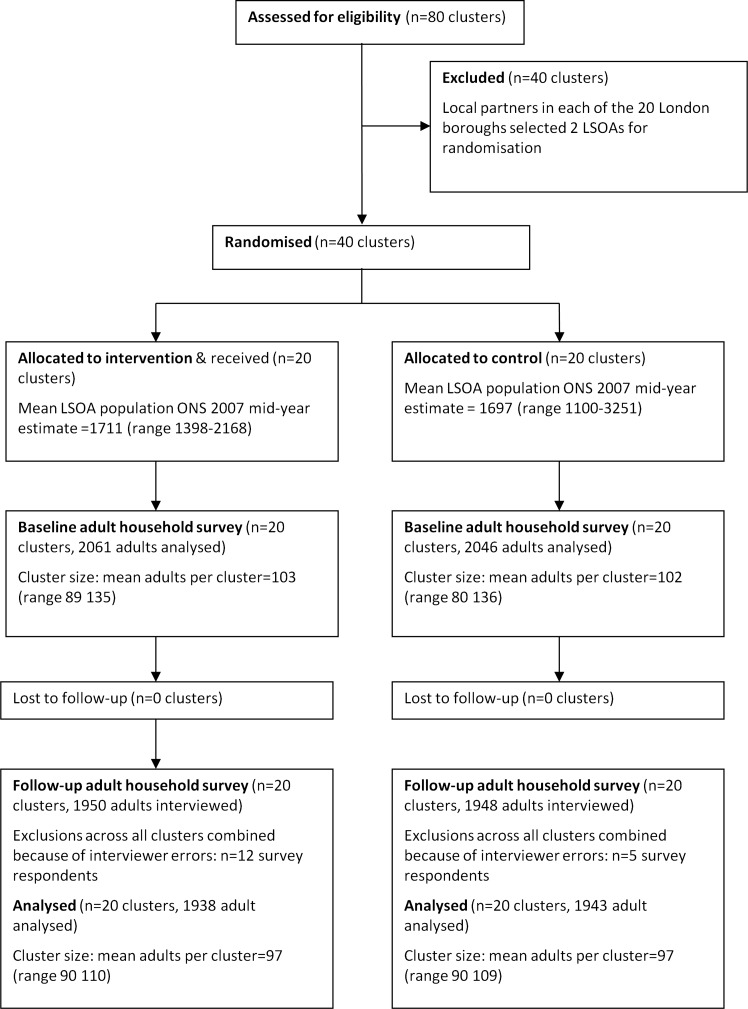

Figure 2 shows the flow of clusters and individuals through the stages of the trial.

Figure 2.

Flow of clusters and individuals through the phases of the Well London cluster-randomised trial.

Comparability of intervention and control neighbourhoods

The baseline survey findings showed intervention and control neighbourhoods to be similar in terms of demographic characteristics and primary health outcomes (table 1).36

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and primary outcomes in intervention and control groups for baseline and follow-up surveys

| Control | Intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n=2046) (95% CI) |

Follow-up (n=1876) (95% CI) |

Baseline (n=2061) (95% CI) |

Follow-up (n=1886) (95% CI) |

|

| Mean age in years | 38.4 (36.6 to 40.2) | 38.7 (37.2 to 40.2) | 38.0 (36.4 to 39.5) | 37.7 (36.4 to 39.1) |

| Gender % female | 52.7 (49.2 to 56.2) | 56.2 (53.1 to 59.3) | 57.5 (54.6 to 60.6) | 57.5 (54.5 to 60.5) |

| Ethnicity, % | ||||

| White British | 28.9 (22.0 to 35.7) | 23.0 (17.4 to 28.6) | 33.2 (25.5 to 40.9) | 25.7 (18.5 to 32.8) |

| White other | 14.0 (9.8 to 18.2) | 13.3 (9.1 to 17.4) | 12.6 (8.9 to 14.2) | 17.5 (12.8 to 22.2) |

| Black Caribbean | 12.1 (8.2 to 15.9) | 10.9 (6.4 to 15.5) | 11.4 (8.7 to 14.2) | 10.4 (8.1 to 12.7) |

| Black African | 18.0 (12.2 to 23.7) | 22.3 (17.0 to 27.6) | 15.6 (11.3 to 19.8) | 21.2 (15.2 to 27.1) |

| Indian/Pakistani/Bangladeshi | 11.6 (4.7 to 18.5) | 19.7 (10.2 to 29.2) | 9.3 (2.1 to 16.5) | 11.7 (5.7 to 17.8) |

| Other Asian | 4.6 (2.1 to 7.0) | 5.0 (2.7 to 7.4) | 4.3 (2.6 to 6.1) | 5.5 (3.9 to 7.1) |

| Mixed | 4.5 (3.3 to 5.6) | 2.2 (1.1 to 3.3) | 5.0 (3.2 to 6.8) | 3.7 (1.7 to 5.6) |

| Other | 6.5 (4.1 to 8.9) | 3.7 (1.5 to 5.8) | 8.6 (4.2 to 12.9) | 4.4 (1.9 to 6.9) |

| Level of educational attainment | ||||

| No formal qualifications | 8.8 (4.1 to 13.5) | 11.7 (6.3 to 17.2) | 11.8 (7.5 to 16.1) | 10.4 (5.6 to 15.2) |

| GCSE or equivalent | 32.2 (27.5 to 37.0) | 28.7 (23.3 to 34.1) | 32.9 (27.4 to 38.5) | 34.1 (29.0 to 39.2) |

| A-level or equivalent | 29.3 (26.0 to 32.6) | 19.9 (17.3 to 22.5) | 27.8 (23.9 to 31.5) | 22.1 (18.6 to 25.7) |

| University degree | 28.5 (23.2 to 33.9) | 36.9 (28.3 to 45.5) | 26.7 (21.7 to 31.8) | 31.3 (25.9 to 36.7) |

| Other | 1.1 (0.1 to 2.2) | 2.8 (1.1 to 4.5) | 0.8 (0.1 to 1.5) | 2.1 (0.4 to 3.7) |

| Employment % in paid employment (full or part-time) | 42.2 (37.1 to 47.3) | 42.8 (37.3 to 48.3) | 42.8 (38.3 to 47.3) | 42.3 (38.6 to 45.9) |

| Healthy eating—meeting five-a-day, % | 38.3 (33.9 to 42.7) | 53.4 (47.6 to 59.3) | 36.6 (33.1 to 40.1) | 55.6 (50.3 to 60.9) |

| Physical activity—meeting 5×30 min per week, % | 66.5 (61.2 to 71.7) | 66.5 (59.0 to 74.0) | 63.4 (56.5 to 70.3) | 68.4 (63.5 to 73.2) |

| Mental health—self-report feeling anxious or depressed % | 18.7 (13.6 to 23.8) | 9.0 (6.4 to 11.5) | 17.8 (13.6 to 22.0) | 8.4 (6.4 to 10.4) |

| Hope Scale Score* | 4.6 (4.5 to 4.7) | 4.8 (4.8 to 4.9) | 4.5 (4.4 to 4.6) | 4.9 (4.8 to 5.1) |

*Higher score indicates greater hopefulness.

GCSE, General Certificate of School Education.

Numbers analysed at follow-up

Out of 3335 addresses visited, at least one interview was conducted at 857, giving a household response rate of 26%. At 873 of 1712 addresses where verbal contact was successfully made interview was refused, giving a household refusal rate of 51%.

Data were analysed from 1938 adults in intervention neighbourhoods and 1948 adults in control neighbourhoods. The levels of missing sociodemographic data for adjustment and subgroup analyses, and missing outcome are shown in online supplementary file 7. None of the sociodemographic or outcome variables had more than 4% of values missing. Respondents in intervention and control neighbourhoods were comparable on sociodemographic characteristics at follow-up (table 1). Baseline and follow-up samples were similar on sociodemographic characteristics (table 1).

Outcomes

Effect-estimates are shown in table 2 (health outcomes) and table 3 (social and community outcomes). Primary outcomes were not significantly different in Well London intervention neighbourhoods compared with control neighbourhoods. Two secondary outcomes showed statistically significant differences between intervention and control neighbourhoods: unhealthy eating score (frequency of fried foods, savoury snacks, cakes/puddings, sweets/chocolate, sugary drinks) was lower in intervention neighbourhoods (mean difference: −0.14, 95% CI −0.27 to −0.02) and the proportion of residents thinking that people living in their neighbourhood pulled together to improve it was higher in intervention neighbourhoods (OR:1.92; 95% CI 1.12 to 3.29).

Subgroup analyses

There was no indication of any differential effects in subgroups defined by age, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment or employment status. Subgroup-specific effect-estimates are shown in online supplementary file 8.

Intervention participation, population turnover and contamination

The rate of participation in any Well London project measured by respondent recall in the follow-up survey was 3.1% (95% CI 1.6% to 4.6%). Of follow-up survey respondents, 41% had moved in since the beginning of intervention delivery, 20% since the final year of delivery, and 7% since the intervention had ended (table 4). However, there were no significant differences in participation rate when any of these three categories of in-migrants were excluded. Restricting the analysis of the outcomes to exclude new in-migrants in these three categories had no impact on the effect-estimates (data not shown). Among follow-up household adult survey respondents in control neighbourhoods, 0.9% (95% CI 0.1% to 1.7%) reported having participated in a project within the Well London programme.

Table 4.

Prevalence of in-migration into intervention LSOAs since key times in the Well London programme and prevalence of self-report intervention participation excluding in-migrants

| Per cent of survey respondents who had arrived in the LSOA since the intervention event (in row headings) (95% CI) | Participation rate if in-migrants are excluded (95% CI) (adjusted for clustering) | |

|---|---|---|

| In-migrant to LSOA since: | ||

| Well London started | 39.8% (35.1 to 44.4) | 3.5%(1.7 to 5.3) |

| Final year of Well London | 17.6% (14.1 to 20.8) | 3.3% (1.9 to 4.8) |

| Well London ended | 5.8% (3.6 to 8.1) | 3.3% (1.8 to 4.8) |

| Total participation rate (all survey respondents) | – | 3.1% (1.6 to 4.6) |

LSOA, lower-super-output-area.

Discussion

Interventions focussing on strengthening communities to improve health and well-being are increasingly used, but there have been few trials of the effectiveness of coproduction-oriented community engagement programmes in delivering community-wide improvements.15 22

Our findings do not provide evidence that the improvements in well-being and social outcomes identified by the non-experimental components of the Well London evaluation28 were achieved neighbourhood-wide. Primary outcomes were not significantly different between intervention and control neighbourhoods. Although there was evidence in intervention neighbourhoods of lower unhealthy eating scores, and higher proportions agreeing that their community pulled together, the public health relevance of these findings is unclear, particularly given the number of outcomes examined and the lack of change in other similar outcome measures.

We should consider potential explanations for these findings, including aspects of study design, population churn and levels of exposure to the intervention. First, there is recognised imprecision in questionnaire-based measurement of healthy eating and physical activity.42 43 This may have generated significant levels of non-differential outcome misclassification, leading in turn to underestimation of true effects, although we cannot exclude the possibility of differential misclassification across study arms. Second, there is potential for sampling bias, given the disappointingly low household response rate of 28%, and this could have acted to obscure either real benefits or non-benefits. Third, population churn in the intervention neighbourhoods was high (40% of follow-up respondents moved in since the start of Well London). There is evidence that coproduced interventions impact health beyond the direct effects of their health content, through enhancing social support networks15–17 and increasing people's control over local environments.18–22 Although exclusion of these in-migrants from analysis made no difference to effect-estimates, there remains the possibility that population churn reduced any indirect effects of the intervention or that those with more positive outcomes (whether directly or indirectly generated) moved out. But even if this were the case, the implication is that such interventions have less chance of success in neighbourhoods with high levels of population churn and, in practice, many deprived neighbourhoods experience similar levels of population churn.

Levels of participation in Well London in intervention neighbourhoods, estimated directly among follow-up questionnaire respondents, were lower than those estimated from the process evaluation.30 Possible explanations include poor recall and brand recognition and higher out-migration among participants. There is evidence that only those individuals who choose actively to engage with a programme experience the processes of personal and social change implied by the underlying theory of empowerment and transformation.15 21 22 The findings reported here as well as those from the accompanying paper,30 and the qualitative component of this trial31 (which demonstrated the reported beneficial effects of active engagement and participation in contrast to a lack of effect among self-identified ‘non-participants’), are consistent with this evidence. It is, therefore, a significant limitation of this study that there was no longitudinal quantitative follow-up of individuals participating in the programmes.

Participation data from the process evaluation28 31 showed significant participation by residents of areas surrounding the trial neighbourhoods, with two-thirds of participants living outside the defined intervention LSOAs. This highlights a tension in the evaluation of community-level programmes that use the area-based approach to community definition and programme delivery (eg, The New Deal44 and the Big Local). Trials are advocated as the most robust evidence of effectiveness,45 but CRTs require that communities be defined in advance. However, our findings suggest that it may be difficult for the geographical limits of the communities engaged by the intervention to be predicted in advance. It is therefore possible that the geographical ‘communities’ in which effects were measured do not correspond closely to the ‘communities’ engaged, which may help to explain our negative findings.

Furthermore, in a highly complex programme, such as Well London, which pragmatically mixes different models of community engagement and health improvement strategies, it is unclear what level and type of ‘participation’ could be expected to impact on which health and social outcomes and to what degree. All Well London activities had the potential to increase individual social networks and support, which could impact on mental well-being. However, only individuals participating in the more traditional health improvement activities would be likely to potentially change their diet and physical activity levels, and spaces on some of these projects were limited in comparison to the size of the populations living in the target neighbourhoods.

Using a CRT, we have asked the ‘simple’46 question ‘did Well London bring about neighbourhood-wide change in the outcomes?’ The balance of the results presented here provide no evidence of this. Low participation rates and population churn likely compromised any impact of the intervention. Given that this trial did not demonstrate that the Well London intervention had any important impact on outcomes, does this suggest that the approach was wrong, or that the implementation of the approach was not good enough? Certainly, the constraints of the funding provided by the Lottery limited the extent to which coproduction could be achieved and delays in implementing the core Well-London Delivery-Team components meant that delivery in many areas was over 2.5 rather than 3.5 years (see online supplementary file 2). Had more time and resources been available for coproduction and intervention development, it may be that the interventions could have been refined to deliver important effects. We believe that we need to establish better development pathways for health improvement interventions and proper investment in these ahead of trialling, if we are to meet the challenges of developing effective interventions for the prevention of chronic illness in the future.

What is already known on this subject?

Recent years have seen an increase in the use of community engagement, coproduction and place-making interventions to promote health and well-being in neighbourhoods. Despite this, evidence for their effectiveness remains limited, and there have been repeated calls to improve the quantity and quality of evaluation.

What this study adds?

This study reports the findings, among adults, of a cluster randomised trial (part of a wider evaluation) of the Well London programme which delivered a multicomponent intervention based on community engagement, coproduction and place-making principles in 20 multiply deprived communities over a 3.5-year period. The findings do not provide evidence supporting the conclusion of non-experimental components of the evaluation that intervention improved health behaviours and social outcomes. Low levels of participation and high levels of population churn may have compromised effectiveness. Imprecision in measurement of health behaviours and well-being, as well as sampling bias may have influenced findings. The paper highlights the inherent tensions in the use of cluster-randomised trials to measure the effects of ‘community’-level interventions since clusters are geographically defined, whereas natural communities may not be. Greater investment in refining such programmes before implementation and trialling will be desirable in the future.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was designed by AR, RH, AD, MP and DM and GP, CB and RH designed the analysis strategy. GP, GY, CB and AR carried out statistical analysis. GP drafted the manuscript and AR edited and finalised the submitted version. MP, RH, GP, CB, PT and PW made critical comments on successive drafts of the manuscript and all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. PT, ES, SL, KL carried out the fieldwork for the surveys.

Funding: This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant number: 083679), Greater London Authority.

Competing interests: The Institute for Health and Human Development, Directed by AR was funded by Big Lottery via the Greater London Authority to deliver the Community Engagement component of the Well London Intervention. The Greater London Authority was commissioned by the Big Lottery to develop and deliver the Well London Intervention.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the ethics committees at University of East London, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Westminster University. It conformed to the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All datasets will be available through the UK Data Archive.

References

- 1.Marmot M. The marmot review: fair society, healthy lives—strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010. London, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buck D, Frosini F. Clustering of unhealthy behaviours over time: Implications for policy and practice. London: The Kings Fund, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitehead M. A typology of actions to tackle social inequalities in health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:473–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Social determinants of health. USA: Oxford University Press, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce N, Davey Smith G. Is social capital the key to inequalities in health? Am J Public Health 2003;93:122–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muntaner C. Commentary: social capital, social class, and the slow progress of psychosocial epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 2004;33:674–80; discussion 700–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clow A, Hamer M. The iceberg of social disadvantage and chronic stress: implications for public health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010;35:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rugulies R. Invited commentary: structure and context matters—the need to emphasize “social” in “psychosocial epidemiology”. Am J Epidemiol 2012;175:620–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wardle J, Steptoe A. Socioeconomic differences in attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyles. J Epidemiol Commun H 2003;57:440–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egan M, Tannahill C, Petticrew M, et al. Psychosocial risk factors in home and community settings and their associations with population health and health inequalities: a systematic meta-review. BMC Public Health 2008;8:239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunter DJ. Public health policy. In: Orme J, Powell J, Taylor P, et al. eds. Public health for the 21st century. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press, McGraw-Hill Education, 2007;24–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackman T. Placing health: neighbourhood renewal, health improvement and complexity. Bristol: The Policy Press, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Community engagement to improve health. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foot J, Hopkins T. A glass half full: how an asset approach can improve community health and well-being. London: Improvement and Development Agency, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliot E, Byrne E, Shirani F, et al. Connected Communities: a review of theories, concepts and interventions relating to community-level strengths and their impact on health and well being. London: Arts and Humanities Research Council, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozbay F, Fitterling H, Charney D, et al. Social support and resilience to stress across the life span: a neurobiologic framework. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2008;10: 304–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, et al. Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry 2007;4:35–40 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallerstein N. Empowerment to reduce health disparities. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2002;59:72–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laverack G. Improving health outcomes through community empowerment: a review of the literature. J Health Popul Nutr 2006;24:113–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Attree P, French B, Milton B, et al. The experience of community engagement for individuals: a rapid review of evidence. Health Soc Care Community 2011;19:250–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milton B, Attree P, French B, et al. The impact of community engagement on health and social outcomes: a systematic review. Community Dev J 2011;47: 316–34. [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, McDaid D, et al. Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: as systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Health Technol Assess 2013. —in press [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hills D. Evaluation of community-level interventions for health improvement: a review of experience in the UK. London: Tavistock Institute, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bond L, Craig P, Egan M, et al. Evaluating complex interventions. Health improvement programmes: really too complex to evaluate? BMJ 2010;340:c1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macintyre S. Good intentions and received wisdom are not good enough: the need for controlled trials in public health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:564–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackenzie M, O'Donnell C, Halliday E, et al. Do health improvement programmes fit with MRC guidance on evaluating complex interventions? BMJ 2010;340:c185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? BMJ 2004;328:1561–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. The Well London Programme—Phase 1 2007–2011: Participant, Project, Community and Programme Level Evaluation. http://www.welllondon.org.uk/1145/research-and-evaluation.html.

- 29.Draper A, Clow A, Lynch R, et al. Buiding a logic model for a complex intervention: a worked example from the Well London CRCT. MRC Population Health Methods and Challenges Conference. Birmingham, UK, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips G, Bottomley C, Schmidt E, et al. Measures of exposure to the Well London Phase-1 intervention and their association with health, wellbeing and social outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:597–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derges J, Clow A, Lynch R, et al. Well London and the benefits of participation: results of a qualitatie study nested in a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wall M, Hayes R, Moore D, et al. Evaluation of community level interventions to address social and structural determinants of health: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2009;9:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Well London: communities working together for a healthier city. London.

- 34.South J, Woodward J, Lowcock D. New beginnings: stakeholder perspectives on the role of health trainers. J R Soc Promot Health 2007;127:224–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips G, Renton A, Moore DG, et al. The Well London program—a cluster randomized trial of community engagement for improving health behaviors and mental wellbeing: baseline survey results. Trials 2012;13:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noble M, Mclennan D, Wilkinson K, et al. The english indices of deprivation 2007. London: Department for Communities and Local Government, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neighbourhood Renewal Unit. The english indices of deprivation 2004: summary (revised). London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayes RJ, Moulton LH. Cluster randomised trials. Boca Ranton, Florida: Chapman & Hall, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corporation S. Stata Statistical Software, release 11. College Station, Texas: Stata Corporation LP, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Craig R, Mindell J. Joint health surveys unit. Health survey for england 2010 volume 2: methods and documentation. London: National Centre for Social Research; Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, UCL, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrari P, Friedenreich C, Matthews CE. The role of measurement error in estimating levels of physical activity. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:832–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kristal AR, Vizenor NC, Patterson RE, et al. Precision and bias of food frequency-based measures of fruit and vegetable intakes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2000;9:939–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popay J, Whitehead M, Badland HM, et al. Evaluating the health inequalities impact of the new deal for communities initiative Society for Social Medicine 56th Annual Scientific Conference. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine London: Journal of Epidemiology and Communtiy Health, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petticrew M, Roberts H. Evidence, hierarchies, and typologies: horses for courses. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003; 57:527–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petticrew M. When are complex interventions ‘complex’? When are simple interventions ‘simple’? Eur J Public Health 2011;21:397–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.