Abstract

Background

A small number of patients with variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) have been treated with intraventicular pentosan polysulfate (iPPS) and extended survival has been reported in some cases. To date, there have been no reports on the findings of postmortem examination of the brain in treated patients and the reasons for the extended survival are uncertain. We report on the neuropathological findings in a case of vCJD treated with PPS.

Methods

Data on survival in vCJD is available from information held at the National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit and includes the duration of illness in 176 cases of vCJD, five of which were treated with iPPS. One of these individuals, who received iPPS for 8 years and lived for 105 months, underwent postmortem examination, including neuropathological examination of the brain.

Results

The mean survival in vCJD is 17 months, with 40 months the maximum survival in patients not treated with PPS. In the 5 patients treated with PPS survival was 16 months, 45 months, 84 months, 105 months and 114 months. The patient who survived 105 months underwent postmortem examination which confirmed the diagnosis of vCJD and showed severe, but typical, changes, including neuronal loss, astrocytic gliosis and extensive prion protein (PrP) deposition in the brain. The patient was also given PPS for a short period by peripheral infusion and there was limited PrP immunostaining in lymphoreticular tissues such as spleen and appendix.

Conclusions

Treatment with iPPS did not reduce the overall neuropathological changes in the brain. The reduced peripheral immunostaining for PrP may reflect atrophy of these tissues in relation to chronic illness rather than a treatment effect. The reason for the long survival in patients treated with iPPS is unclear, but a treatment effect on the disease process cannot be excluded.

Keywords: CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE, PRION, NEUROPATHOLOGY

Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) is a zoonotic prion disease, linked to infection with the agent of bovine spongiform encephalopathy. There is no proven treatment for the underlying disease process. The suggestion, based on cell culture results, that quinacrine might be an effective treatment has not been confirmed by assessments of the efficacy of this drug.1 2 In 2004 animal studies provided evidence that intraventricular pentosan polysulfate (iPPS) might be an effective treatment in prion diseases3 and following a hearing in the High Court, which supported the provision of this treatment in vCJD, a small number of patients were treated with iPPS. One patient did not appear to respond to this treatment,4 but three others have been reported to have extended survival in comparison with that expected in vCJD5 6 and a fifth patient has been confirmed by reports in the media to have had long survival.

The reason for the extended survival is unknown and possibilities include a treatment effect, selection for treatment of patients likely to have long survival, high quality care, including early treatment of infection and chance.7 An observational study of the efficacy of iPPS concluded that there was some suggestion of a treatment effect7 and the Medical Research Council review on which this paper was based suggested that PPS was a potential therapy for prion disease. The possibility of a treatment effect has been raised by the report of a reduction in the amount of disease-associated prion protein (PrP) in the brain of a case of sporadic CJD treated with iPPS.8 This report describes the postmortem findings in a case of vCJD treated with iPPS.

Methods

The National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit obtains data on all cases of vCJD in the UK. The methodology of the Unit has been described in detail previously. Information on clinical features, including date of onset and death, together with details of drug therapy is obtained on all cases. Detailed information on the surgical procedures and PPS infusion in this case were provided by contributing authors (NVT, PKN). The results of the whole blood assay for vCJD were provided by author SM.

Postmortem examination was carried out by author DS at the request of the coroner and tissues were examined at the National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit using a standard protocol described previously. The methodologies for other investigations in this case, including western blot analysis, protease-resistant PrP (PrPres) sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation and genetic analysis have also been described previously.9

Ethical approval for the acquisition and use of autopsy material for research at the Edinburgh brain bank is covered by 11/ES/0022.

Results

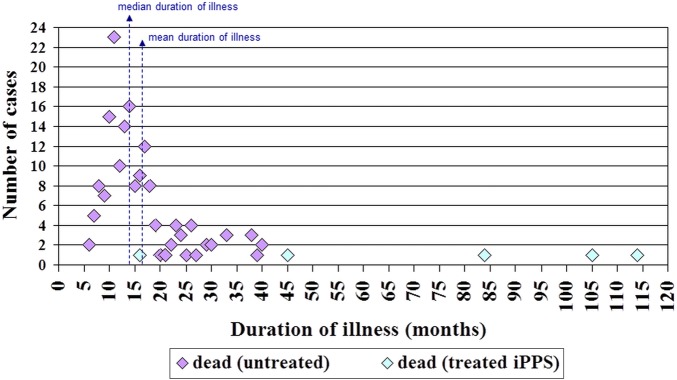

There have been 177 deaths from vCJD in the UK (as of August 2013) and the mean survival is 17 months from disease onset to death. Five of these cases received treatment with iPPS and the duration of illness in these cases is shown in figure 1, together with that of non-treated cases. The treated case that survived 105 months is described below.

Figure 1.

Duration of illness in cases of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) (n=176).

Case report

An 18-year-old girl presented in September 2003 with a 9 month history of personality change, anxiety, tearfulness and withdrawal. She performed unexpectedly badly in school examinations and in July developed forgetfulness and unsteadiness walking. The cognitive problems progressed and were associated with fleeting delusions and auditory hallucinations. She developed unpleasant sensory symptoms in the feet, slurring of speech and fidgety movements of the hands and arms. On examination there was cognitive impairment, together with dysarthria, limb and gait ataxia and choreiform movements in the limbs.

There was a past history of vertigo in 2002, with normal MRI brain scan, but no history of treatment with human growth hormone or prior neurosurgery and no family history of a similar disorder. MRI brain scan in 2003 showed the ‘pulvinar’ sign and no other cause for the presentation was apparent on extensive investigation. The clinical diagnosis was probable vCJD. Testing for abnormal PrP in blood in August 2011, using the novel assay described by Edgeworth et al,10 was negative.

After careful and full consideration of ethical and legal issues in a patient who lacked capacity, the clinicians accepted the wishes of the patient's family to begin treatment with iPPS which commenced in October 2003. Biventricular catheters were inserted using a stereotactic procedure and a programmable pump was implanted subcutaneously. Treatment with iPPS was given at a dosage of 11 μg/kg/day and following replacement of the catheters in 2011 the treatment was continued at 11 μg/kg/day up until the patient died. In 2007, additional systemic treatment with PPS was given by programmable pump via the external jugular vein in a dosage increasing from 1µg/kg/day to 4 μg/kg/day. The treatment was stopped after 12 weeks because of persisting infection and haematoma at the pump site, and the pump was removed.

Despite the treatment there was neurological deterioration and by December 2003 the patient was unable to walk and needed assistance to dress, bathe, wash and feed. There was difficulty with swallowing and a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was fitted in June 2005. Over subsequent years the patient's condition was relatively static with only subtle further clinical deterioration. She was wheelchair bound and fully dependent for activities of daily living. There was no verbal or clear sentient response, but at times the parents reported transient responsiveness to outside stimuli such as the pet dog or family videos, contrary to clinical observations. The patient received excellent care from her family, with additional nursing support and regular treatment by a physiotherapist.

The patient died suddenly in November 2011 and postmortem was carried out at the request of the coroner. The patient's family gave consent for detailed pathological investigation of the brain and peripheral tissues.

Postmortem results

The general postmortem revealed pulmonary oedema and mild bronchopneumonia. The brain showed severe atrophy and weighed 775 g. Tubing for the delivery system for PPS passed through the brain into the lateral ventricles. The other main organs were unremarkable.

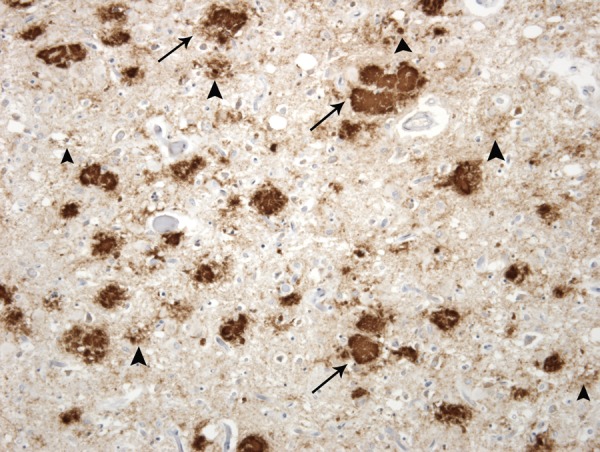

Examination of the fixed brain showed marked atrophy of the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres, brainstem and midbrain. On cross section, the hippocampus was relatively spared, but the deep grey matter nuclei of the cerebral hemispheres were atrophic and the subcortical white matter was firm and discoloured. No evidence of old or recent haemorrhage was identified. Microscopic examination confirmed marked atrophy of the major grey matter structures, accompanied by severe neuronal loss and widespread gliosis. The white matter was also markedly gliotic and showed secondary myelin loss as a consequence of axonal degeneration. Immunocytochemistry for PrP showed massive accumulation of abnormal PrP throughout the cerebral cortex and cerebellum, and also in the basal ganglia, thalamus and hypothalamus and to a lesser extent the brainstem. The pattern of deposition included florid plaques, small cluster plaques and some granular deposits (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prion protein (PrP) immunohistochemistry in the frontal cortex of the brain shows extensive deposition of disease-associated PrP (brown) in large florid plaques (arrows), cluster plaques (large arrowheads) and fine granular deposits (small arrowheads). 3F4 anti-PrP antibody with haematoxylin counterstain,×40.

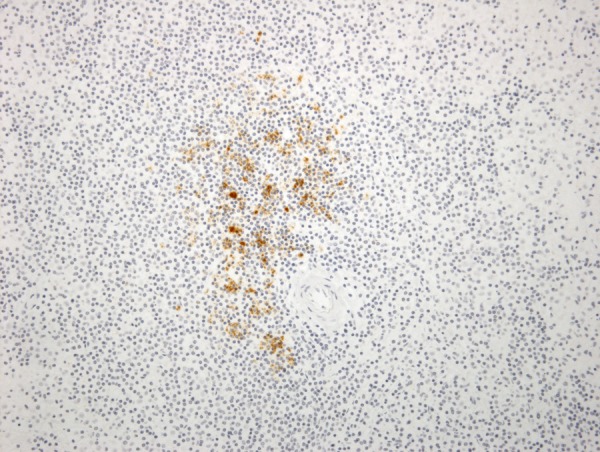

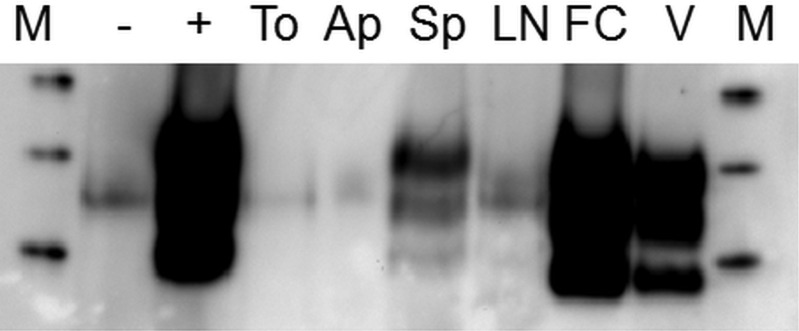

Sections of the appendix, lymph nodes, spleen and tonsil showed no evidence of abnormal PrP accumulation on routine immunohistochemistry. However, repeat immunohistochemical studies using an enhanced visualisation system showed PrP accumulation in follicular dendritic cells within the tonsil, lymph node, appendix and spleen.11 The spleen showed depletion of white pulp, with sparse follicular labelling (figure 3), which was confirmed on paraffin-embedded tissue blot studies for protease-resistant prion proteinres. Western blot analysis of frozen tissue samples from the cerebrum and cerebellum found high levels of PrPres with a type 2B isoform characteristic of vCJD,12 with highest levels in the occipital cortex and lowest levels in the thalamus. No specific signals for type 2B PrPres were obtained using the centrifugal enrichment method on samples of appendix, tonsil, lymph node or spleen. The sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation method allowed for detection of type 2B PrPres in the spleen, but not in appendix, lymph node or tonsil samples (figure 4). The patient was a methionine homozygote at codon 129 in the PrP gene.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry for prion protein (PrP) in the spleen shows labelling of follicular dendritic cells (brown) within a splenic follicle adjacent to an arteriole. 3F4 anti-PrP antibody with haematoxylin counterstain,×20.

Figure 4.

Sodium phosphotungstic acid (NaPTA) precipitation/western blotting analysis of lymphoreticular tissue samples for the presence of protease-resistant prion protein (PrPres). Samples of tonsil (To), appendix (Ap), spleen (Sp) and lymph node (LN) homogenate, each corresponding to 50 mg of tissue, from the index case, were analysed alongside spleen samples (− and +) from a control case with a non-Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) neurological disease. One of the latter control samples (+) had been spiked with brain frontal cortex homogenate from the index case corresponding to 300 µg of tissue prior to NaPTA precipitation. Brain frontal cortex homogenate from the index case (50 µg) and variant CJD frontal cortex homogenate reference standard (200 µg) were analysed directly, without prior NaPTA precipitation (FC and V, respectively). The molecular weight markers (M) are 40 kDa, 30 kDa and 20 kDa from top to bottom.

The pathological features confirmed the diagnosis of vCJD.

Discussion

The data presented in this paper suggests that treatment with iPPS may extend survival in vCJD. Four out of five treated patients survived for periods significantly longer than untreated patients (figure 1) and this suggests that chance alone is an unlikely explanation. All the treated cases received excellent nursing care, assisted feeding and active treatment of intercurrent illness, but this was also true for many of the ‘untreated’ cases of vCJD . There is an inverse relationship between age and survival in human prion diseases13 and the three longest survivors treated with iPPS were aged less than 20 years at the time of starting treatment. However, there have been 31 other cases of vCJD in the UK with an onset age less than 20 years in which the mean survival was only 20 months. Many of these cases received active treatment (but not iPPS) from an early stage and case selection is unlikely to explain the extended survival in the iPPS group.

If iPPS influences the underlying disease process, the evidence from the postmortem examination of the brain in this case does not suggest that the treatment has reduced the extent or severity of the brain pathology. In fact the pathological changes were severe including the extent of abnormal PrP deposition and this perhaps parallels the observed neurological deterioration in the index case and the severe neurological deficits present in the latter stages of the illness. One potential explanation for the extended survival is that iPPS treatment resulted in relative preservation of the brainstem nuclei and the sudden death, without a clear cause on the general autopsy, may indicate that death may have been due to a combination of central and peripheral processes.

The relative paucity of abnormal PrP in lymphoreticular system (LRS) might be as a result of the systemic treatment with PPS. However, atrophy of LRS in chronic illness is well recognised14 and it may be that the depletion of white matter pulp, observed in this case, may reflect a more general atrophy of LRS as an epiphenomenon rather than an effect of PPS treatment on the levels of peripheral abnormal PrP. The blood-based assay for vCJD has a reported sensitivity of 71% in known cases of vCJD, therefore no clear conclusion can be drawn from this test being negative10

In conclusion the evidence suggests that iPPS treatment may have extended survival in vCJD and that this is likely related to an effect on the underlying disease process. Although iPPS is clearly not a cure for vCJD, the fact that such a treatment has had a significant biological effect provides encouragement for the future development of treatment for human prion diseases.

Acknowledgments

The blood based assay for vCJD was performed at the MRC Prion Unit by Dr Graham Jackson and reviewed and reported by Professor John Collinge. The patient was reviewed by SM as part of his participation in the National Prion Monitoring Cohort study (Department of Health). The authors are grateful to Dr Mark Head, Dr Diane Ritchie, Dr Alexander Peden and Helen Yull for their expertise in the analysis of prion protein in tissue samples, and to Linda McCardle and Margaret LeGrice for expert neuropathological laboratory work.

Footnotes

Contributors: PKN was responsible for clinical data on the case. NVT was responsible for providing information on the operative procedures described in the article. DS was responsible for the pathological data provided in the article. SM was responsible for the results of the disease specific blood test described in the paper. RSGK contributed to the clinical data in the paper. RGW contributed to the clinical data in the paper and wrote the first draft of the article. JWI was responsible for the specialised neuropathological data in the paper. All authors contributed to writing the final version of the paper.

Funding: The brain bank at the National CJD Research and Surveillance Unit is part of the Edinburgh Brain Bank funded by MRC (G1100616). The National Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Research and Surveillance Unit is funded by the Department of Health and the Scottish Government.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Lothian Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Haik S, Brandel JP, Salomon BA, et al. Compassionate use of quinacrine in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease fails to show significant effects. Neurology 2004;63:2413–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collinge J, Gorham M, Hudson F, et al. Safety and efficacy of quinacrine in human prion disease (PRION-1 study): a patient-preference trial. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:334–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doh-ura K, Ishikawa K, Murakami-Kubo I, et al. Treatment of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy by intraventricular drug infusion in animal models. J Virol 2004;78:4999–5006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whittle IR, Knight RSG, Will RG. Unsuccessful intraventricular pentosan polysulphate treatment of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148:677–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parry A, Baker I, Stacey R, et al. Long term survival in a patient with variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease treated with intraventricular pentosan polysulphate. JNNP 2007;78:733–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Todd NV, Morrow J, Doh-ura K, et al. Cerebroventricular infusion of pentosan polysulphate in human variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Infection 2005;50:394–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bone I, Belton L, Walker AS, et al. Intraventricular pentosan polysulphate in human prion diseases: an observational study in the UK. European J Neurology 2008;15:458–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terada T, Tsuboi Y, Obi T, et al. Less protease-resistant PrP in a patient with sporadic treated with intraventricular pentosan polysulphate. Acta Neurol Scand 2010;121:127–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heath CA, Cooper SA, Murray K, et al. Validation of diagnostic criteria for variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann Neurol 2010;67:761–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edgeworth JA, Farmer M, Sicilia A, et al. Detection of prion infection in variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a blood-based assay. Lancet 2011; 377:487–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilton DA, Ghani AC, Conyers L, et al. Prevalence of lymphoreticular prion protein accumulation in UK tissue samples. J Pathol 2004; 203:733–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peden A, McCardle L, Head MW, et al. Variant CJD infection in the spleen of a neurologically asymptomatic UK adult patient with haemophilia. Haemophilia 2010;16:296–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pocchiari M, Puopolo M, Croes E, et al. Predictors of survival in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and other human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Brain 2004;127:2348–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trewby PN, Chipping PM, Palmer SJ, et al. Splenic atrophy in adult coeliac disease: is it reversible? Gut 1981;22:628–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]