Abstract

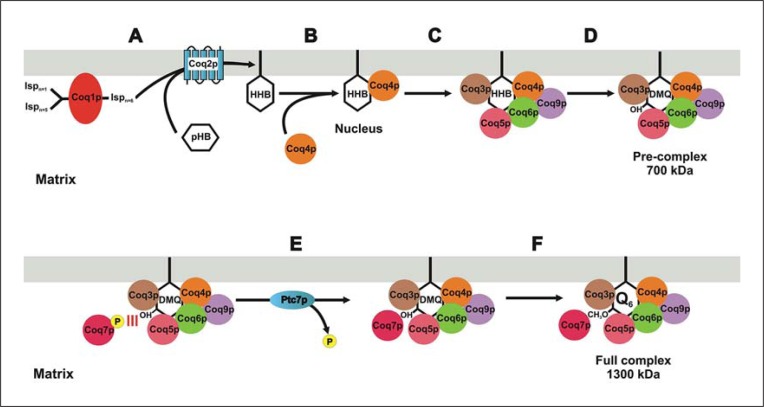

Coenzyme Q (CoQ) is a mitochondrial lipid, which functions mainly as an electron carrier from complex I or II to complex III at the mitochondrial inner membrane, and also as antioxidant in cell membranes. CoQ is needed as electron acceptor in β-oxidation of fatty acids and pyridine nucleotide biosynthesis, and it is responsible for opening the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. The yeast model has been very useful to analyze the synthesis of CoQ, and therefore, most of the knowledge about its regulation was obtained from the Saccharomyces cerevisiae model. CoQ biosynthesis is regulated to support 2 processes: the bioenergetic metabolism and the antioxidant defense. Alterations of the carbon source in yeast, or in nutrient availability in yeasts or mammalian cells, upregulate genes encoding proteins involved in CoQ synthesis. Oxidative stress, generated by chemical or physical agents or by serum deprivation, modifies specifically the expression of some COQ genes by means of stress transcription factors such as Msn2/4p, Yap1p or Hsf1p. In general, the induction of COQ gene expression produced by metabolic changes or stress is modulated downstream by other regulatory mechanisms such as the protein import to mitochondria, the assembly of a multi-enzymatic complex composed by Coq proteins and also the existence of a phosphorylation cycle that regulates the last steps of CoQ biosynthesis. The CoQ biosynthetic complex assembly starts with the production of a nucleating lipid such as HHB by the action of the Coq2 protein. Then, the Coq4 protein recognizes the precursor HHB acting as the nucleus of the complex. The activity of Coq8p, probably as kinase, allows the formation of an initial pre-complex containing all Coq proteins with the exception of Coq7p. This pre-complex leads to the synthesis of 5-demethoxy-Q6 (DMQ6), the Coq7p substrate. When de novo CoQ biosynthesis is required, Coq7p becomes dephosphorylated by the action of Ptc7p increasing the synthesis rate of CoQ6. This critical model is needed for a better understanding of CoQ biosynthesis. Taking into account that patients with CoQ10 deficiency maintain to some extent the machinery to synthesize CoQ, new promising strategies for the treatment of CoQ10 deficiency will require a better understanding of the regulation of CoQ biosynthesis in the future.

Key Words: Coenzyme Q, Mitochondria, Protein complex, Respiration, Ubiquinone, Yeast

When coenzyme Q (CoQ) was discovered in 1957 by F.L. Crane [Crane et al., 1957] as a novel component of the respiratory electron chain system, the future and crucial role of CoQ was not completely revealed. However, CoQ discovery was not an incidental event; it was part of a general study to analyze mitochondrial components [Crane, 2007]. Obviously, the importance of CoQ as a mitochondrial electron carrier was reinforced when CoQ was chosen as the lipid electron carrier by the electro-osmotic theory [Mitchell, 1961]. After that, the important function carried out by CoQ in mitochondria to provide energy to the cell has been demonstrated. This function obscures that CoQ is involved in other cell functions that are needed for an adequate metabolism as they are not visible under normal levels of CoQ. However, it is likely that patients affected by CoQ deficiency exhibit adequate energy generation, which implies that other CoQ-dependent functions are responsible for their characteristic phenotype non-related with bioenergetics. In this sense, CoQ is required as electron acceptor in some reactions of β-oxidation [Frerman, 1988] and nucleotide synthesis [Jones, 1980; Nagy et al., 1992], it regulates the opening of the mitochondrial potential transition pore [Fontaine et al., 1998; Fontaine and Bernardi, 1999; Walter et al., 2000], and it is also required by the uncoupler protein UCP1 to transfer protons at the matrix [Echtay et al., 2000]. Out of the mitochondria, CoQ has been described as a direct lipophilic antioxidant [Do et al., 1996; Bentinger et al., 2007] that can also help to recycle other lipid or water soluble antioxidants such as vitamin E [Beyer, 1994; Kagan et al., 1998] or ascorbic acid [Santos-Ocaña et al., 1995, 1998; Gómez-Díaz et al., 1997a, b; Arroyo et al., 2004].

CoQ10 deficiency diseases are a subgroup of rare disorders included in the family of mitochondrial diseases [Quinzii et al., 2007a]. CoQ10 deficiencies can be classified in 5 groups according to the specific affection of organs and systems [Quinzii et al., 2008], all related to a decrease of ATP availability and a mitochondrial dysfunction. In the last years, patients with mutations in genes directly associated with the CoQ10 synthesis have been studied [Lopez et al., 2006; López-Martín et al., 2007; Mollet et al., 2008; Lagier-Tourenne and Tazir, 2008; Duncan et al., 2009; Heeringa et al., 2011; Salviati et al., 2012] which allowed a classification into primary (PDSS1, PDSS2, COQ2, COQ4, COQ6, COQ9, and ADCK3) or secondary CoQ10 deficiency (when other genes non-related to CoQ10 are affected) [DiMauro, 2006].

In general, patients with CoQ10 deficiency show a wide range of CoQ10 content [Quinzii et al., 2007a, b] that correlates with the severity of the phenotype. In patients with a high deficiency, there is a general problem of energy availability that is usually incompatible with birth or leads to death at young age. Moderate levels of CoQ10 allow development up to birth, and some patients reach juvenile or adult ages with several types of clinical symptoms, some of them produced by an energy shortage, but others are related with defects in additional functions of CoQ10 such as the synthesis of pyridine-nucleotides [López-Martín et al., 2007]. Low CoQ10 levels are also detected in patients with mitochondrial diseases non-related to genes involved in CoQ10 biosynthesis (secondary deficiency), in patients with neurodegenerative diseases [Shults et al., 2002; Battino et al., 2003; Mancuso et al., 2006; Stack et al., 2008] and also in aged people [Turunen et al., 2004].

Oral supplementation is so far the best approach to increase CoQ10 levels in patients [Ogasahara et al., 1989; Rotig et al., 2000; Salviati et al., 2005]. However, several studies have reported that the improvement obtained by oral supplementation does not generally apply to all cases and depends on the symptoms detected in patients and the genetic origin of the deficiency [Musumeci et al., 2001; Lamperti et al., 2003; Aure et al., 2004; Quinzii et al., 2005; Artuch et al., 2006; Mollet et al., 2008; Lagier-Tourenne and Tazir, 2008]. The treatment of patients has been afforded by the use of CoQ10 analogs such as MitoQ [Tauskela, 2007] or idebenone [Meier and Buyse, 2009]. The main effect of those molecules is to improve the antioxidant protection [Becker et al., 2010; Smith and Murphy, 2010], but only a low effect has been obtained at the respiratory chain [Plecita-Hlavata et al., 2009].

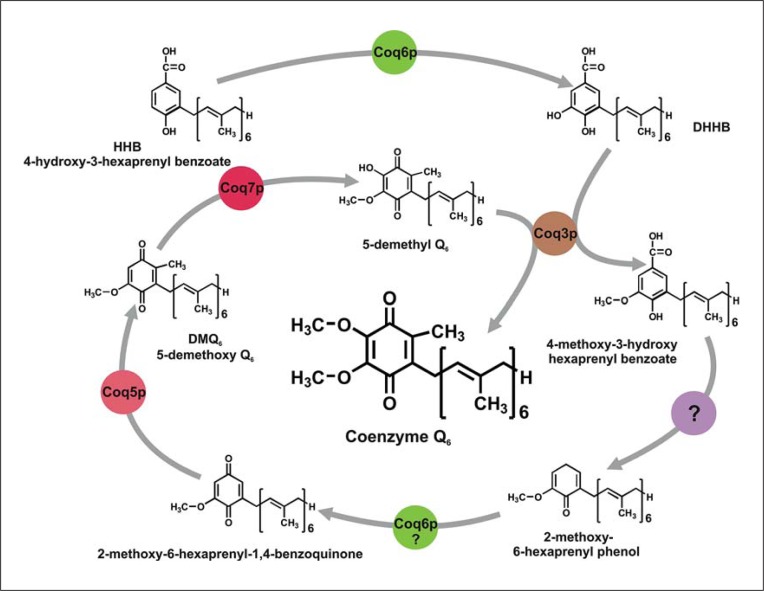

A complementary alternative may be to increase the endogenous CoQ10 synthesis in all tissues. Some approaches based on the use of peroxisome activators through PPAR-α such as di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) [Bentinger et al., 2003] or polyisoprenoid epoxides [Bentinger et al., 2008a, b] have been described. However, both approaches have not been tested in humans and do not affect the CoQ10 biosynthetic pathway specifically. In all cases, it is tempting to speculate that induction of the endogenous CoQ biosynthesis could be the best solution since the CoQ10 biosynthetic machinery is present to some extent in patients independently of the severity of the deficiency. Finding targets to increase the CoQ10 biosynthesis will be our goal in the next years, but it requires a better understanding of the regulation of CoQ10 biosynthesis. This is the focus of this review: to analyze the state of the art of regulation of CoQ biosynthesis. However, although human CoQ10 deficiency has been an emerging topic in the last decade, most of the information has been obtained from the yeast model Saccharomyces cerevisiae. This review focuses on this organism, but known details of CoQ10 biosynthesis in mammals or human are also included. For a better understanding of the CoQ biosynthetic pathway, a general scheme for yeast is depicted in figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Biosynthetic pathway of CoQ in yeast. The pathway of CoQ6 biosynthesis starting from the first molecule with the quinone structure (polar ring and isoprene chain). This molecule is produced by the action of Coq1p and Coq2p that are not included in the scheme. Coq6p is a monooxygenase that catalyzes the DHHB synthesis and probably the synthesis of 2-methoxy-6-hexaprenyl-1,4-benzoquinone; Coq3p is an O-methyltransferase that catalyzes 2 O-methylations, Coq5p catalyzes a C-methylation and Coq7p catalyzes the hydroxylation of DMQ6. For the decarboxylation of 4-methoxy-3-hydroxy hexaprenyl benzoate, the responsible enzyme has not been found. Other proteins such as Coq4p and Coq8p are required to synthesize CoQ6 but do not show catalytic activity.

CoQ and the Bioenergetic Metabolism

Taking into account the main function of CoQ as a component of the respiratory chain, it is reasonable to hypothesize a connection between the regulation of CoQ biosynthesis and the respiratory function. Obviously, this points to a big difference between human and yeast models; yeasts are facultative aerobic fermenters, they can usually grow as fermenters in glucose even in presence of oxygen, but can also grow as respiratory organism in the absence of fermentable carbon sources [Gancedo, 1998]. This allows studying the transition from fermentation to respiration as a model of CoQ6 biosynthesis activation since this molecule is needed preferentially during respiration. Results from Sippel et al. [1983] demonstrated this relationship; higher levels of glucose in the culture media clearly decrease the amount of CoQ6 in yeasts. This amount was inversely correlated with the amount of a quinone precursor, 3,4-dihydroxy-5-hexaprenyl benzoate (DHHB), that was previously described as a precursor of CoQ6 biosynthesis in eukaryotic cells [Goewert et al., 1981]. The repression produced by an excess of glucose is a typical feature of some yeasts such as S. cerevisiae which is mediated via the repression of Snf1p kinase [Gancedo, 1998], a protein complex that belongs to the family of AMPK kinases [Santangelo, 2006]. Snf1p is kept inactive in the presence of glucose, but at levels under 0.5%, the repression is lost, and Snf1p induces the expression of downstream genes that are required for the use of other carbon sources such as ethanol, lactate or glycerol. At this point, it is very interesting to analyze the effect of cAMP [Sippel et al., 1983], since high levels of CoQ6 are correlated with high levels of cAMP. The addition of cAMP in the presence of 10% glucose shows CoQ6 levels similar to those obtained with non-repressing conditions. That supports the idea that phosphorylation may be a regulatory element to consider in CoQ6 biosynthesis. It is possible to argue that PKA activation may be a general regulatory element for mitochondrial metabolism, but the specific accumulation of DHHB before the first methylation reaction of the pathway points to a specific mechanism involving the phosphorylation of Coq proteins (see fig. 1).

The decrease of glucose concentration in yeast growing in YPD medium and the raising of ethanol modify considerably the metabolic state of yeast. When glucose is exhausted, ethanol starts to be consumed, but it requires a modification of metabolism that produces a shift named post-diauxic-shift or PDS [Pedruzzi et al., 2000]. This growth stage initiates a respiratory metabolism that needs a higher amount of CoQ6. It has been reported that CoQ6 and DMQ6 (5-demethoxy-coenzyme Q6) levels are affected in yeast cultured in YPD: initially, DMQ6 is accumulated until PDS initiation, and then DMQ6 decreases and CoQ6 becomes the predominant quinone in the yeast [Padilla et al., 2009]. These facts support the idea of a DMQ6 to CoQ6 conversion after PDS [Padilla et al., 2009]. In the same study, this change of quinone concentration is correlated with the expression of several COQ genes such as COQ3, COQ4, COQ5, COQ7, and COQ8. A similar result has been found in high-throughput mRNA expression studies [DeRisi et al., 1997] for all COQ genes.

DMQ6 is not the only accumulated intermediate in yeast during the growth in YPD. 4-Hydroxy-3-hexaprenyl benzoate (HHB) is also accumulated at a high proportion (∼80%) against total quinones during the exponential phase of growth [Poon et al., 1995] but is a minor component at stationary phase. This fact agrees with the idea that CoQ6 biosynthesis shows at least 2 different intermediates, the first at the initial stages of the specific quinone ring formation (HHB) and also a second molecule (DMQ6) close to the last stage of synthesis. HHB may be produced during the initial exponential phase because there is high availability of energy produced by fermentation, and DMQ6 is produced at the initial PDS growth to accumulate an intermediate that is ready to be converted in CoQ6 when it is required. In this sense, DMQ6 is accumulated in wild-type yeast and does show neither mitochondrial electron transport nor antioxidant protection properties [Padilla et al., 2004].

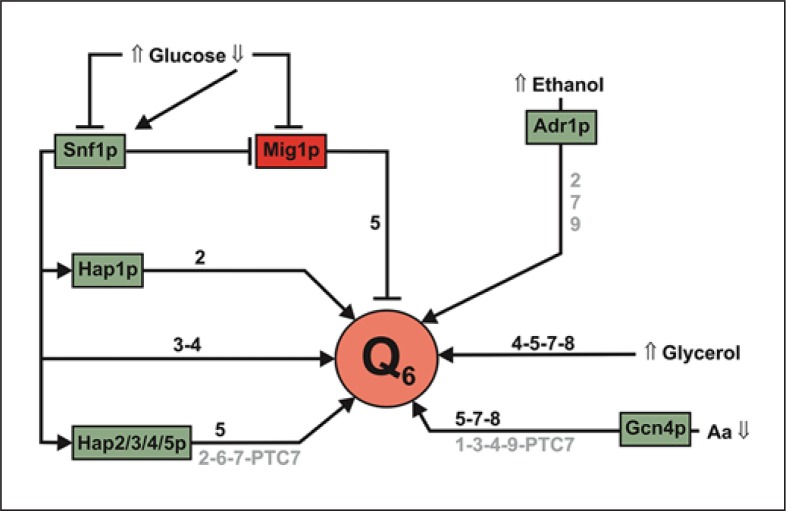

The simplest method to detect respiratory-deficient yeasts is the growth in glycerol as carbon source. This is useful to study CoQ6 biosynthesis because the change of glucose to glycerol-based media induces the expression of COQ5 [Hagerman et al., 2002], although in the particular case of COQ5, the growth in oleic acid as carbon source produces a higher induction than glycerol. Oleic acid degradation in yeast requires its oxidation in peroxisomes, while CoQ6, unlike in other organisms, is not required as an electron acceptor [Hiltunen et al., 2003; Antonenkov et al., 2010]. Therefore, the higher requirements of CoQ6 under oleic acid growth must be related to the mitochondrial electron transport and also to the protection of peroxisome membranes against the oxidative stress generated in this cellular compartment. However, in the previously cited study [Hagerman et al., 2002], the determination of CoQ6 under glycerol growth was not performed. Recently, it has been reported that the growth in glycerol increases the accumulation of CoQ6 in wild-type yeast [Padilla et al., 2009] with the simultaneous reduction of DMQ6. In the same study, the glycerol growth induces the expression of several COQ genes such as COQ5, COQ7 and COQ8, the relative mRNA level being 3 times higher than that obtained from glucose growth. The COQ4 gene is another gene that is upregulated by growth in YPG, similar to some other mitochondrial proteins such as subunits of the complex IV [Belogrudov et al., 2001]. In summary, some COQ genes are upregulated when yeast is grown under respiratory conditions. However, little is known about the transcription factors involved in this regulation. There is one study that specifically analyzes transcription factors involved in the synthesis of CoQ6 [Hagerman and Willis, 2002], but unfortunately, this study only focuses on the COQ5 gene. This gene is regulated by Hap2p, a subunit of the HAP complex (heme activated-glucose repressed CCAAT-binding complex) that is a global regulator of respiratory gene expression (fig. 2). Also, COQ5 expression is down-regulated by Mig1p, a transcription factor that collaborates in glucose repression. Mig1p is phosphorylated by Snf1p (which is active with low glucose and dephosphorylated by Glc7p). Other studies devoted to a general transcriptional analysis have shown that COQ2 is upregulated by Hap1p, a transcription factor that produces a response based on the levels of heme and oxygen [Harbison et al., 2004; Hickman and Winston, 2007]. Using the platform YEASTRACT [Monteiro et al., 2008; Abdulrehman et al., 2011], it is possible to find potential promoter sequences recognized by transcription factors involved in the mitochondrial respiratory metabolism (table 1) such as Hap3p, Hap4p, Hap5p, and Adr1p. Curiously, the amino acid starvation through the transcription factor Gcn4p induces the expression of most COQ genes (documented or potential regulation). Glutamate is considered as the node of metabolism required for the biosynthesis of 16 amino acids. Since the source of glutamate is α-ketoglutarate, a Krebs cycle intermediate, the activation of mitochondria and then the respiratory metabolism is a required factor to increase the amino acid biosynthesis. A general view of this regulatory process is shown in figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Summary of the transcriptional regulation of CoQ6 biosynthesis depending on carbon sources and the bioenergetic metabolism. CoQ6 biosynthesis is modulated by several transcription factors related to the response to different fermentable and non-fermentable carbon sources, and also by amino acid deprivation. Green factors indicate activation and red factors correspond to repression. Black numbers indicate documented expression and grey numbers correspond to a putative expression of the respective COQ genes and PTC7.

Table 1.

COQ gene regulation by transcription factors involved in the bioenergetic metabolism

| Transcription factor | Documented regulation | Potential regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Hap1p | COQ2 [Harbison et al., 2004] | COQ2 |

| Hap2p | COQ5 [Hagerman and Willis, 2002] | COQ2, COQ6, COQ7 |

| Hap3 | COQ2, COQ6, PTC7 | |

| Hap4 | COQ2, COQ6, PTC7 | |

| Hap5 | COQ2, COQ6, PTC7 | |

| Mig1p | COQ5 [Hagerman and Willis, 2002] | |

| Gcn4p | COQ5, COQ8 [Moxley et al., 2009], COQ7 [Staschke et al., 2010] | COQ8, COQ1, COQ3, COQ4, COQ9, PTC7 |

| Adr1p | COQ2, COQ7, COQ9 |

Little is known about the effect of the bioenergetic metabolism in mammalian or human cells in CoQ biosynthesis. The most relevant data comes from nutritional interventions such as caloric restriction (CR). CR in yeast induces a life span extension by the activation of the respiratory metabolism [Lin et al., 2002; Ocampo et al., 2012]. A similar effect was found in HeLa cells cultured in serum from rats subjected to CR conditions: at the same time, CR promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and improves the bioenergetic efficiency [Lopez-Lluch et al., 2006]. An increased mitochondrial biogenesis was produced in muscle from human individuals subjected to CR conditions [Civitarese et al., 2007], although in both cases CoQ10 level was not measured. However, CoQ determination in 2 CR-treated murine models, mice [Lass et al., 1999] and rats [Kamzalov and Sohal, 2004], demonstrates that CoQ level decreases along the life, but it is higher compared to control in aged CR animals. In mammalian cells, the activation of the mitochondrial metabolism by CR and probably by other interventions increases the amount of CoQ.

CoQ Biosynthesis and Oxidative Stress

The antioxidant protection is a second function of CoQ [Frei et al., 1990; Bentinger et al., 2007]. In yeast, the better characterized antioxidant role of CoQ6 was the protection of phospholipid peroxidation detected in COQ3 null mutants (coq3) growing in the presence of linolenic acid [Do et al., 1996]. That effect applies to all CoQ6-deficient strains [Schultz and Clarke, 1999]. The incubation of wild-type yeast with linolenic acid upregulates several genes such as COQ3 and COQ7 [Padilla et al., 2009] and also drives the DMQ6 conversion to CoQ6. It is very interesting that this conversion requires the hydroxylase activity of Coq7p and the O-methyltransferase activity of Coq3p. However, the translational or post-translational nature of this regulation was not determined. Other oxidant compounds such as hydrogen peroxide did not affect COQ gene expression [Padilla et al., 2009]. Using the platform YEASTRACT [Monteiro et al., 2008; Abdulrehman et al., 2011], it is possible to find potential promoter sequences recognized by transcription factors involved in the induction of antioxidant defenses such as Msn2p, Msn4p, Yap1p, and Hsf1p (table 2). Msn2/4p are activated under stress conditions, Yap1p is specific to the antioxidant response to H2O2 and Cd2+ and Hsf1p produces a response against heat shock. All COQ genes are upregulated (documented or potential regulation) by a general situation of stress, but only COQ1 shows a specific response to H2O2 and only COQ4 and COQ6 for hyperthermia.

Table 2.

COQ gene regulation by transcription factors involved in oxidative stress response

| Transcription factor | Documented regulation | Potential regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Msn2/4p | COQ1 [Lai et al., 2005] | COQ1, COQ2, COQ4, COQ6, COQ7, COQ9 COQ3, COQ4, COQ5, COQ6, COQ7, COQ8 |

| COQ6 [Berry and Gasch, 2008] | ||

| Yap1p | COQ1 [Thorsen et al., 2007] | |

| Hsf1p | COQ4, COQ6 [Eastmond and Nelson, 2006] |

In this case, in mammalian cells, it is possible to find 2 examples of the oxidative stress role to promote CoQ biosynthesis upregulation. Serum deprivation is a method widely used to produce a moderate oxidative stress treatment that increases mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and Ca2+ release [Kuznetsov et al., 2008]. This method is comparable to others that induce cell death based on oxidative stress treatments [Kuznetsov et al., 2011], apoptosis being the most important consequence of serum deprivation. Previously, several studies have demonstrated that exogenous CoQ10 shows a protective role against oxidative stress. This is the case of CEM-C7H2 cells that undergo apoptosis after serum deprivation conditions but are protected in presence of exogenous CoQ10 [Fernández-Ayala et al., 2000]. This protection is produced by the inhibition of ceramide release and caspase-3 activation through the inhibition of plasma membrane-bound neutral sphingomyelinase [Navas et al., 2002]. The mild oxidative stress produced by serum deprivation not only induces apoptosis but also increases CoQ10 levels in the plasma membrane [Barroso et al., 1997]. It suggests a regulatory function of serum deprivation probably through oxidative stress signals. However, in those studies only plasma membrane CoQ10 levels were measured but not the total amount or the synthesis rate. It is possible that another mechanism such as CoQ10 transport from mitochondria or other endomembranes [Fernandez-Ayala et al., 2005; Padilla-López et al., 2009] was the origin of CoQ10 accumulation instead of an increased synthesis. More convincing results regarding the molecular mechanism of oxidative stress to induce CoQ biosynthesis were obtained from the effect of the chemotherapeutic drug camptothecin (CPT). This drug is a topoisomerase inhibitor that induces DNA damage and oxidative stress [Gorman et al., 1997] and therefore apoptosis. Initially, the oxidative stress generated is unlikely to be associated with DNA damage, but the effect of CPT is inversely related with reduced glutathione content [Troyano et al., 2001]. CPT treatment in several cancer cell lines increases the amount of total CoQ10 [Brea-Calvo et al., 2006], this increase being dose-dependent and inhibited by the presence of antioxidants. The CPT mechanism to increase CoQ10 biosynthesis requires the activation of the COQ7 gene by the transcription factor NF-κB [Brea-Calvo et al., 2009]. COQ7 in yeast is an important component of the CoQ biosynthetic complex catalyzing a reaction of hydroxylation and also shows a crucial function on the regulation of the CoQ biosynthetic complex activity in yeast.

Evidence of a CoQ Biosynthetic Complex in Yeast

Biosynthesis of CoQ requires the participation of at least 9 genes in yeast directly involved in the synthesis of the quinone ring. A crucial question in the field has been to identify whether Coq proteins adopt a linear pathway as in E. coli [Gibson and Young, 1978] or require the formation of a protein complex. Several lines of evidence strongly support the second option, the existence of a biosynthetic complex of CoQ6.

Nature of Precursors in Null and Point Mutants

A common property for null COQ mutants is the accumulation of HHB (fig. 1) from COQ3 to COQ9 genes even for regulatory proteins such as Coq4p [Poon et al., 1997; Gin et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2005]. However, some point mutants in COQ genes accumulate the expected intermediate or diagnostic precursor. In the COQ7 gene, several point mutants such as qm30 or e2519 [Padilla et al., 2004] or E194K [Tran et al., 2006] accumulate DMQ6 instead of HHB. The DMQ6 synthesis requires the participation of several Coq proteins, and it is located in the final steps of the biosynthetic pathway (fig. 1), supporting the idea of the existence of a complex to produce CoQ6. Several point mutants in the COQ series such as COQ4, COQ5, COQ8 [Baba et al., 2004; Marbois et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2011] are able to partially restore the steady state of other Coq proteins. In the case of COQ4 or COQ8, the lack of diagnostic precursors could be expected given that these proteins play a regulatory role. More interesting is the case of Coq5p, a C-methyltransferase. This effect suggests that most Coq proteins show a dual role, catalytic and structural, namely some mutations can remove the enzymatic function, but the presence of protein in mitochondria supports the complex assembly. Another important fact is analyzing the effect produced by null mutations on the presence of other Coq proteins in yeast mitochondria.

Steady-State Levels of Coq Proteins in Mitochondria

The steady-state levels of Coq proteins constitute an interesting approach to analyze the complex existence. If a possible component of a multi-enzymatic complex is absent in mitochondria by a null mutation in another gene, it constitutes an indicator of the complex existence. The first study performed to analyze the steady-state levels of Coq proteins was focused on the protein Coq3p [Hsu et al., 2000], basically thanks to the existence of specific antibodies and the possibility to measure the O-methyltransferase activity. It was the first of numerous analyses conducted in the laboratory of Dr. C.F. Clarke [Baba et al., 2004; Gin and Clarke, 2005; Hsieh et al., 2007; Marbois et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2011, 2012]. With these data, it was possible to establish 3 types of Coq proteins: (a) proteins always present in mitochondria independent of the null mutant analyzed, such as Coq1p, Coq2p, Coq5p, and Coq8p, (b) proteins that show a lower expression, such as Coq3p and Coq4p, and (c) proteins that completely disappear, such as Coq6p, Coq7p and Coq9p. With the premise that if a subunit of a complex cannot be assembled, it will be removed and degraded from mitochondria [Arlt et al., 1998; Rugarli and Langer, 2012], the proteins unaffected in null mutants (Coq1p, Coq2p, Coq5p and Coq8p) must be independent of the complex formation. In the case of Coq1p and Coq2p, it is possible that their contribution to the complex formation is the synthesis of a quinone-like precursor that is required to start the complex assembly (fig. 3A, B). More difficult to explain is the function of Coq5p and Coq8p. These proteins are likely required to initiate the complex and can be located at the mitochondria even if the complex is not produced.

Fig. 3.

Model of the biosynthetic complex for CoQ6. The model is a summary of already published data and non-well-defined ideas shown in the text. A The precursor. The first quinone-like molecule is the 4-hydroxy-3-hexaprenyl benzoate (HHB) that is produced by the action of Coq1p and Coq2p in mitochondria. Both proteins are required to synthesize CoQ6 but are not present in the complex. HHB is accumulated at the exponential phase of growth during fermentation. B The nucleation. Coq4p recognizes HHB and starts the nucleation process. The action of Coq4p must be triggered by the mere accumulation of Coq4p produced when cells reach the PDS. However, previous activation by a kinase cannot be excluded. C Formation of the 700-kDa pre-complex. During the PDS, the activity of Coq4p bound to HHB starts the recruitment of Coq proteins to produce the 700-kDa complex or pre-complex. D Pre-complex activity. Because the pre-complex does not contain Coq7p, the activity of the pre-complex facilitates the accumulation of DMQ6 during PDS. E The role of Ptc7p on the final assembly. Coq7p has been phosphorylated previously and cannot be a component of the pre-complex due to steric hindrance or charge repulsion with some components of the pre-complex. The phosphatase Ptc7p dephosphorylates Coq7p, erasing the repulsion from the pre-complex. F The full complex assembly. Coq7p bound to the pre-complex catalyzes the penultimate step of CoQ6 biosynthesis after the formation of the full 1,300-kDa complex.

Components of the CoQ6 Biosynthesis Complex

The presence of a Coq protein in mitochondria itself does not demonstrate the participation in a biosynthetic complex and does not allow to deduce the complex composition. It was possible to obtain information using new approaches such as detection of mitochondrial complexes by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) and BN-PAGE. Initially, a 700-kDa complex containing Coq3p, Coq4p, Coq6p, and Coq9p but not Coq1p or Coq5p was detected using SEC [Marbois et al., 2005; Hsieh et al., 2007]. The detection of O-methyltransferase activity in the same fractions demonstrates the presence of Coq3p and also validates the method. BN-PAGE analysis confirmed the presence of Coq3p, Coq4p, Coq5p, and Coq9p in the 700-kDa complex [Tauche et al., 2008; Marbois et al., 2009]. A second complex was detected by SEC at a high molecular weight (1,300 kDa) containing Coq3p, Coq4p and Coq7p [Tran et al., 2006; Marbois et al., 2009].

In summary, the CoQ6 complex assembly is produced in 2 steps; the initial one is the formation of a pre-complex of 700 kDa containing most of the Coq proteins that are affected in null mutants, with the exception of Coq7p (fig. 3C). The pre-complex accumulates the precursor of Coq7p, DMQ6 (fig. 3D). The second step is the full complex assembly after the addition of Coq7p (fig. 3E, F) and produces CoQ6. Coq8p remains as an intriguing component that must play an extremely important role in complex formation although there is no evidence of its presence in both complexes. Coq8p overexpression studies point out the crucial function of this protein in CoQ6 biosynthesis.

Overexpression Studies

Suppression studies by gene overexpression are very useful tools to analyze the structure or composition of multi-enzymatic complexes. In the specific case of CoQ6, this analysis was performed with COQ8 overexpression in several null mutant strains. The first null mutant analyzed was the COQ7 null mutant (coq7) that was subjected to COQ8 and COQ4 gene overexpression because at this time both genes did not show any catalytic activity [Padilla et al., 2009]. However, only COQ8 overexpression allowed the accumulation of DMQ6 in coq7 mutants. This was the starting point of a set of experiments clarifying the structure of the CoQ6 biosynthetic complex. It was used to demonstrate the role of Coq6p as C5-hydroxylase. The addition of vanillic (4-hydroxy-3-methoxy benzoate) acid together with COQ8 overexpression restored the CoQ6 synthesis in a COQ6 null mutant strain (coq6) [Ozeir et al., 2011]; vanillic acid bypassed the lack of Coq6p, but COQ8 overexpression made possible the complex stabilization required to modify vanillic acid to CoQ6. Without the addition of exogenous molecules, it was possible to analyze the accumulation of diagnostic intermediates and the steady-state levels of Coq proteins after COQ8 overexpression [Xie et al., 2012]. That method validates the DMQ6 accumulation in coq7 mutants produced by complex stabilization, and it also demonstrates the C-methyltransferase activity of Coq5p. The same approach applied to coq3 and coq4 mutants (COQ8 overexpression) seems to be ineffective because it only produces the accumulation of HHB. For coq3 mutants, it yields the expected results, but for coq4 mutants, it supports the idea of an initial function of Coq4p in the assembly of the complex.

These lines of evidence demonstrate that CoQ6 biosynthesis in yeast is the result of the assembly of a multi-enzymatic complex composed of some Coq catalytic proteins and also other Coq regulatory proteins. This complex seems to be nucleated around the first quinone molecule (HHB) and Coq4p (fig. 3A, B). Most of the Coq proteins are bound to the initial HHB-Coq4p to produce the 700-kDa pre-complex (fig. 3C) that accumulates DMQ6. Coq7p is bound to the pre-complex when high levels of CoQ6 are required. The remaining question to solve is the nature of the mechanism which makes possible the full complex containing Coq7p (fig. 3F) that finally produces CoQ6.

Regulation of CoQ Biosynthesis by Phosphorylation

The protein encoded by COQ7 seems to be a regulatory element in CoQ6 biosynthesis. Coq7p catalyzes the hydroxylation of DMQ6 (fig. 1). DMQ6 is accumulated in wild-type strains [Sippel et al., 1983; Padilla et al., 2004, 2009] and in some point mutants of COQ7 growing in glucose. The model of CoQ6 biosynthesis indicated above shows that Coq7p does not seem to be required for the 700-kDa pre-complex, but it requires the participation of Coq7p to produce CoQ6 in the 1,300-kDa complex (fig. 3F). Coq7p has been described as a protein that can be phosphorylated by Coq8p [Tauche et al., 2008; Xie et al., 2011], but recently Coq7p phosphorylation has been associated with the metabolic state of yeast [Martin-Montalvo et al., 2011]. The introduction of 3 phosphosite modifications in Coq7p detected by a NetPhos analysis [Ingrell et al., 2007] leads to non-phosphorylatable proteins (Ser20, Ser28, Thr32 to Ala20, Ala28, Ala32). The expression of the triple modified version of COQ7 in a coq7 null mutant dramatically increases CoQ6 up to 250%. When CoQ6 is needed, the dephosphorylation of Coq7p must be a requisite to facilitate the interaction of Coq7p with the pre-complex rendering the full 1,300-kDa complex (fig. 3F).

In S. cerevisiae, 7 of the 33 phosphatases [Sakumoto et al., 1999] encoded in the yeast genome are mitochondrial phosphatases [Claros and Vincens, 1996], but in most cases the function is known with the exception of Ptc7p, which belongs to the PPM family [Martin-Montalvo et al., 2013]. Ptc7p dephosphorylates Coq7p in vivo and in vitro [Martin-Montalvo et al., 2013], and it is expressed in non-fermentable carbon sources and in oxidative stress conditions. Coq7p phosphorylated in vitro by PKA is dephosphorylated by Ptc7p, corroborating that the lack of PTC7 leads to the accumulation of phosphorylated Coq7p in vivo. A direct relationship between Coq7p and Ptc7p was demonstrated when the non-phosphorylatable version of Coq7p (COQ7p-AAA) was expressed in a PTC7 null mutant strain (ptc7) [Martin-Montalvo et al., 2013]. This overexpression produces a high amount of CoQ6 (250% compared to control) since phosphatase is not needed when Coq7p is constitutively dephosphorylated. This supports completely the function of Ptc7p as Coq7p-phosphatase and points out the Ptc7p functions as a regulator of CoQ6 biosynthesis in particular and as regulator of mitochondrial metabolism in general.

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The biosynthesis of CoQ is regulated in order to match mainly 2 cellular processes, the bioenergetic metabolism and the antioxidant defense. At the transcriptional level, higher CoQ requirements caused by the carbon source in yeast or the availability of nutrients in yeasts and mammalian cells modify dramatically the expression of genes involved in CoQ synthesis. In a similar way, oxidative stress generated by different agents such as chemical reagents or serum deprivation induces the specific expression of genes involved in CoQ synthesis. Clearly, the induction of COQ gene expression increases the amount of CoQ, but this expression is modulated by new regulatory steps associated with the protein import to mitochondria and mainly with post-translational modifications such as the CoQ biosynthetic complex assembly and a phosphorylation cycle. Complex assembly is as process involving 3 steps: nucleation, pre-complex assembly and full complex assembly. The phosphorylation of Coq7p and the consequent dephosphorylation by the phosphatase Ptc7p is the mechanism explaining the last step. This model for regulation of CoQ6 biosynthesis introduces a target to improve the CoQ biosynthesis, the triangle composed by the subject of phosphorylation, Coq7p, the phosphatase, Ptc7p, and the kinase, probably Coq8p.

However, CoQ biosynthesis is a topic far from being completed and the model depicted here (fig. 3) will require further research. Several methods must be applied to finish the description of a model for CoQ biosynthesis. It will require obtaining crystallographic models for Coq proteins and also the application of massive proteomic analysis, both promising strategies in order to analyze Coq protein relationships and possible interactions with other mitochondrial complexes or proteins.

The studies performed on regulation of CoQ6 biosynthesis in yeast can be transferred to the human model in which most of the Coq proteins are homologous to yeast proteins and can complement successfully null mutant strains [López-Martín et al., 2007; Casarin et al., 2008; Heeringa et al., 2011]. A better knowledge of this mechanism will be useful to find potential targets for new therapeutic approaches to improve the level of endogenous CoQ10 in patients affected by primary or secondary deficiency.

Acknowledgement

The work was supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spanish PI11/00078, Junta de Andalucía P08-CTS-03988 and by the International Q10 Association ‘Phosphorylation based regulation of coenzyme Q biosynthesis in yeast’. A.M.-M. received a predoctoral fellowship from the Consejería de Innovación Ciencia y Empresa, Junta de Andalucía (Spain). I.G.-M. received a predoctoral fellowship from the Plan Propio of the Universidad Pablo de Olavide de Sevilla. T.P.V. and P.G.D. received a predoctoral fellowship from the CIBERER-ISCIII (Spain). We thank Gloria Brea Calvo and Ignacio Guerra Pérez for the critical reading of the manuscript, Plácido Navas for supporting the work and also Ana Sánchez Cuesta for her technical help.

References

- Abdulrehman D, Monteiro PT, Teixeira MC, Mira NP, Lourenço AB, et al. YEASTRACT: providing a programmatic access to curated transcriptional regulatory associations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through a web services interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D136–D140. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonenkov VD, Grunau S, Ohlmeier S, Hiltunen JK. Peroxisomes are oxidative organelles. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:525–537. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlt H, Steglich G, Perryman R, Guiard B, Neupert W, Langer T. The formation of respiratory chain complexes in mitochondria is under the proteolytic control of the m-AAA protease. EMBO J. 1998;17:4837–4847. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo BA, Villalba JMJM, Arroyo A, Rodríguez-Aguilera JCJ, Santos-Ocaña C, Navas P. Stabilization of extracellular ascorbate mediated by coenzyme Q transmembrane electron transport. Methods Enzymol. 2004;378:207–217. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)78017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artuch R, Brea-Calvo G, Briones P, Aracil A, Galvan M, et al. Cerebellar ataxia with coenzyme Q10 deficiency: diagnosis and follow-up after coenzyme Q10 supplementation. J Neurol Sci. 2006;246:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aure K, Benoist JF, Ogier de Baulny H, Romero NB, Rigal O, Lombes A. Progression despite replacement of a myopathic form of coenzyme Q10 defect. Neurology. 2004;63:727–729. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134607.76780.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba SW, Belogrudov GI, Lee JC, Lee PT, Strahan J, et al. Yeast Coq5 C-methyltransferase is required for stability of other polypeptides involved in coenzyme Q biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10052–10059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313712200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso MP, Gomez-Diaz C, Villalba JM, Buron MI, Lopez-Lluch G, Navas P. Plasma membrane ubiquinone controls ceramide production and prevents cell death induced by serum withdrawal. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1997;29:259–267. doi: 10.1023/a:1022462111175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battino M, Bompadre S, Leone L, Devecchi E, Degiuli A, et al. Coenzyme Q, vitamin E and Apo-E alleles in Alzheimer disease. Biofactors. 2003;18:277–281. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520180231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker C, Bray-French K, Drewe J. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of idebenone. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2010;6:1437–1444. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2010.530656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belogrudov GI, Lee PT, Jonassen T, Hsu AY, Gin P, Clarke CF. Yeast COQ4 encodes a mitochondrial protein required for coenzyme Q synthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;392:48–58. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentinger M, Turunen M, Zhang XX, Wan YJ, Dallner G. Involvement of retinoid X receptor alpha in coenzyme Q metabolism. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:795–803. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01447-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentinger M, Brismar K, Dallner G. The antioxidant role of coenzyme Q. Mitochondrion. 2007;7(suppl):S41–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentinger M, Tekle M, Brismar K, Chojnacki T, Swiezewska E, Dallner G. Polyisoprenoid epoxides stimulate the biosynthesis of coenzyme Q and inhibit cholesterol synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2008a;283:14645–14653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentinger M, Tekle M, Brismar K, Chojnacki T, Swiezewska E, Dallner G. Stimulation of coenzyme Q synthesis. Biofactors. 2008b;32:99–111. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520320112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DB, Gasch AP. Stress-activated genomic expression changes serve a preparative role for impending stress in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4580–4587. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer RE. The role of ascorbate in antioxidant protection of biomembranes: interaction with vitamin E and coenzyme Q. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1994;26:349–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00762775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brea-Calvo G, Rodríguez-Hernández A, Fernández-Ayala DJ, Navas P, Sánchez-Alcázar JA. Chemotherapy induces an increase in coenzyme Q10 levels in cancer cell lines. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:1293–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brea-Calvo G, Siendones E, Sanchez-Alcazar JA, de Cabo R, Navas P. Cell survival from chemotherapy depends on NF-kappaB transcriptional up-regulation of coenzyme Q biosynthesis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casarin A, Jimenez-Ortega JC, Trevisson E, Pertegato V, Doimo M, et al. Functional characterization of human COQ4 a gene required for coenzyme Q10 biosynthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civitarese AE, Carling S, Heilbronn LK, Hulver MH, Ukropcova B, et al. Calorie restriction increases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis in healthy humans. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claros MG, Vincens P. Computational method to predict mitochondrially imported proteins and their targeting sequences. Eur J Biochem. 1996;241:779–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane FL. Discovery of ubiquinone (coenzyme Q) and an overview of function. Mitochondrion. 2007;7(suppl):S2–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane FL, Hatefi Y, Lester RL, Widmer C. Isolation of a quinone from beef heart mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1957;25:220–221. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(57)90457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRisi JL, Iyer VR, Brown PO. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science. 1997;278:680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMauro S. Mitochondrial myopathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18:636–641. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000245729.17759.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do TQ, Schultz JR, Clarke CF. Enhanced sensitivity of ubiquinone-deficient mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to products of autoxidized polyunsaturated fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7534–7539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AJ, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Meunier B, Costello H, Hargreaves IP, et al. A nonsense mutation in COQ9 causes autosomal-recessive neonatal-onset primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency: a potentially treatable form of mitochondrial disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:558–566. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond DL, Nelson HC. Genome-wide analysis reveals new roles for the activation domains of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae heat shock transcription factor (Hsf1) during the transient heat shock response. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32909–32921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602454200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echtay KS, Winkler E, Klingenberg M. Coenzyme Q is an obligatory cofactor for uncoupling protein function. Nature. 2000;408:609–613. doi: 10.1038/35046114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ayala DJ, Martín SF, Barroso MP, Gómez-Díaz C, Villalba JM, et al. Coenzyme Q protects cells against serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis by inhibition of ceramide release and caspase-3 activation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:263–275. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.2-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Ayala DJ, Brea-Calvo G, Lopez-Lluch G, Navas P. Coenzyme Q distribution in HL-60 human cells depends on the endomembrane system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1713:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine E, Bernardi P. Progress on the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: regulation by complex I and ubiquinone analogs. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1999;31:335–345. doi: 10.1023/a:1005475802350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine E, Ichas F, Bernardi P. A ubiquinone-binding site regulates the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25734–25740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei B, Kim MC, Ames BN. Ubiquinol-10 is an effective lipid-soluble antioxidant at physiological concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4879–4883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frerman FE. Acyl-CoA dehydrogenases, electron transfer flavoprotein and electron transfer flavoprotein dehydrogenase. Biochem Soc Trans. 1988;16:416–418. doi: 10.1042/bst0160416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancedo JM. Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:334–361. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.334-361.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson F, Young IG. Isolation and characterization of intermediates in ubiquinone biosynthesis. Methods Enzymol. 1978;53:600–609. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)53061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gin P, Clarke CF. Genetic evidence for a multi-subunit complex in coenzyme Q biosynthesis in yeast and the role of the Coq1 hexaprenyl diphosphate synthase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2676–2681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gin P, Hsu AY, Rothman SC, Jonassen T, Lee PT, et al. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae COQ6 gene encodes a mitochondrial flavin-dependent monooxygenase required for coenzyme Q biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25308–25316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goewert RR, Sippel CJ, Olson RE. Identification of 3,4-dihydroxy-5-hexaprenylbenzoic acid as an intermediate in the biosynthesis of ubiquinone-6 by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry. 1981;20:4217–4223. doi: 10.1021/bi00517a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Díaz C, Rodríguez-Aguilera JC, Barroso MP, Villalba JM, Navarro F, et al. Antioxidant ascorbate is stabilized by NADH-coenzyme Q10 reductase in the plasma membrane. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1997a;29:251–257. doi: 10.1023/a:1022410127104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Díaz C, Villalba JM, Pérez-Vicente R, Crane FL, Navas P. Ascorbate stabilization is stimulated in rho(0)HL-60 cells by CoQ10 increase at the plasma membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997b;234:79–81. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman A, McGowan A, Cotter TG. Role of peroxide and superoxide anion during tumour cell apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 1997;404:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RA, Willis RA. The yeast gene COQ5 is differentially regulated by Mig1p, Rtg3p and Hap2p. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1578:51–58. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RA, Trotter PJ, Willis RA. The regulation of COQ5 gene expression by energy source. Free Radic Res. 2002;36:485–490. doi: 10.1080/10715760290021360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbison CT, Gordon DB, Lee TI, Rinaldi NJ, Macisaac KD, et al. Transcriptional regulatory code of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2004;431:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nature02800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SF, Chernin G, Chaki M, Zhou W, Sloan AJ, et al. COQ6 mutations in human patients produce nephrotic syndrome with sensorineural deafness. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2013–2024. doi: 10.1172/JCI45693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman MJ, Winston F. Heme levels switch the function of Hap1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae between transcriptional activator and transcriptional repressor. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7414–7424. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00887-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltunen JK, Mursula AM, Rottensteiner H, Wierenga RK, Kastaniotis AJ, Gurvitz A. The biochemistry of peroxisomal β-oxidation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:35–64. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh EEJ, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Tran UC, Saiki R, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Coq9 polypeptide is a subunit of the mitochondrial coenzyme Q biosynthetic complex. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;463:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu AY, Do TQ, Lee PT, Clarke CF. Genetic evidence for a multi-subunit complex in the O-methyltransferase steps of coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2000;1484:287–297. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingrell CR, Miller ML, Jensen ON, Blom N. NetPhosYeast: prediction of protein phosphorylation sites in yeast. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:895–897. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A, Gin P, Marbois BN, Hsieh EJ, Wu M, et al. COQ9 a new gene required for the biosynthesis of coenzyme Q in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31397–31404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones ME. Pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthesis in animals: genes, enzymes, and regulation of UMP biosynthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:253–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan VE, Tyurina YY, Witt E. Role of coenzyme Q and superoxide in vitamin E cycling. Subcell Biochem. 1998;30:491–507. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1789-8_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamzalov S, Sohal RS. Effect of age and caloric restriction on coenzyme Q and alpha-tocopherol levels in the rat. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1199–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov AV, Smigelskaite J, Doblander C, Janakiraman M, Hermann M, et al. Survival signaling by C-RAF: mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and Ca2+ are critical targets. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2304–2313. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00683-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov AV, Kehrer I, Kozlov AV, Haller M, Redl H, et al. Mitochondrial ROS production under cellular stress: comparison of different detection methods. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;400:2383–2390. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-4764-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagier-Tourenne C, Tazir M. ADCK3, an ancestral kinase, is mutated in a form of recessive ataxia associated with coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:661–672. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L, Kosorukoff AL, Burke PV, Kwast KE. Dynamical remodeling of the transcriptome during short-term anaerobiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae differential response and role of Msn2 and/or Msn4 and other factors in galactose and glucose media. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4075–4091. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.4075-4091.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamperti C, Naini A, Hirano M, De Vivo DC, Bertini E, et al. Cerebellar ataxia and coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Neurology. 2003;60:1206–1208. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055089.39373.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass A, Forster MJ, Sohal RS. Effects of coenzyme Q10 and alpha-tocopherol administration on their tissue levels in the mouse: elevation of mitochondrial alpha-tocopherol by coenzyme Q10. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:1375–1382. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Kaeberlein M, Andalis A, Sturtz L, Defossez PA, et al. Calorie restriction extends Saccharomyces cerevisiaelifespan by increasing respiration. Nature. 2002;418:344–348. doi: 10.1038/nature00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez LC, Schuelke M, Quinzii CM, Kanki T, Rodenburg RJ, et al. Leigh syndrome with nephropathy and CoQ10 deficiency due to decaprenyl diphosphate synthase subunit 2 (PDSS2) mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:1125–1129. doi: 10.1086/510023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Lluch G, Hunt N, Jones B, Zhu M, Jamieson H, et al. Calorie restriction induces mitochondrial biogenesis and bioenergetic efficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1768–1773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510452103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Martín JM, Salviati L, Trevisson E, Montini G, DiMauro S, et al. Missense mutation of the COQ2 gene causes defects of bioenergetics and de novo pyrimidine synthesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1091–1097. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso M, Choub A, Filosto M, Petrozzi L, Cafforio G, et al. Coenzyme Q10 and neurological diseases: an update. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2006;3:378–382. [Google Scholar]

- Marbois B, Gin P, Faull KF, Poon WW, Lee PT, et al. Coq3 and Coq4 define a polypeptide complex in yeast mitochondria for the biosynthesis of coenzyme Q. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20231–20238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501315200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marbois B, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Clarke CF. The yeast Coq4 polypeptide organizes a mitochondrial protein complex essential for coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Biochim Biophys. 2009;1791:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Montalvo A, Gonzalez-Mariscal I, Padilla S, Ballesteros M, Brautigan DL, et al. Respiratory-induced coenzyme Q biosynthesis is regulated by a phosphorylation cycle of Cat5p/Coq7p. Biochem J. 2011;114:107–114. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Montalvo A, Gonzalez-Mariscal I, Pomares-Viciana T, Padilla-Lopez S, Ballesteros M, et al. The phosphatase Ptc7 induces coenzyme Q biosynthesis by activating the hydroxylase Coq7 in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:28126–28137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.474494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier T, Buyse G. Idebenone: an emerging therapy for Friedreich ataxia. J Neurol. 2009;256(suppl):25–30. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-1005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. Coupling of phosphorylation to electron and hydrogen transfer by a chemi-osmotic type of mechanism. Nature. 1961;191:144–148. doi: 10.1038/191144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollet J, Delahodde A, Serre V, Chretien D, Schlemmer D, et al. CABC1 gene mutations cause ubiquinone deficiency with cerebellar ataxia and seizures. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro PT, Mendes ND, Teixeira MC, d'Orey S, Tenreiro S, et al. YEASTRACT-DISCOVERER: new tools to improve the analysis of transcriptional regulatory associations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D132–136. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxley JF, Jewett MC, Antoniewicz MR, Villas-Boas SG, Alper H, et al. Linking high-resolution metabolic flux phenotypes and transcriptional regulation in yeast modulated by the global regulator Gcn4p. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6477–6482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811091106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musumeci O, Naini A, Slonim AE, Skavin N, Hadjigeorgiou GL, et al. Familial cerebellar ataxia with muscle coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Neurology. 2001;56:849–855. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.7.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy M, Lacroute F, Thomas D. Divergent evolution of pyrimidine biosynthesis between anaerobic and aerobic yeasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8966–8970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.8966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navas P, Fernandez-Ayala DM, Martin SF, Lopez-Lluch G, De Caboa R, et al. Ceramide-dependent caspase 3 activation is prevented by coenzyme Q from plasma membrane in serum-deprived cells. Free Radic Res. 2002;36:369–374. doi: 10.1080/10715760290021207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo A, Liu J, Schroeder EA, Shadel GSS, Barrientos A. Mitochondrial respiratory thresholds regulate yeast chronological life span and its extension by caloric restriction. Cell Metab. 2012;16:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasahara S, Engel AG, Frens D, Mack D. Muscle coenzyme Q deficiency in familial mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2379–2382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozeir M, Mühlenhoff U, Webert H, Lill R, Fontecave M, Pierrel F. Coenzyme Q biosynthesis: Coq6 is required for the C5-hydroxylation reaction and substrate analogs rescue Coq6 deficiency. Chem Biol. 2011;18:1134–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla S, Jonassen T, Jiménez-Hidalgo M, Fernández-Ayala DJM, López-Lluch G, et al. Demethoxy-Q, an intermediate of coenzyme Q biosynthesis, fails to support respiration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and lacks antioxidant activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25995–26004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla S, Tran UC, Jiménez-Hidalgo M, López-Martín JM, Martín-Montalvo A, et al. Hydroxylation of demethoxy-Q6 constitutes a control point in yeast coenzyme Q6 biosynthesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:173–186. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-López S, Jiménez-Hidalgo M, Martín-Montalvo A, Clarke CF, Navas P, et al. Genetic evidence for the requirement of the endocytic pathway in the uptake of coenzyme Q6 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:1238–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedruzzi I, Bürckert N, Egger P, De Virgilio C. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ras/cAMP pathway controls post-diauxic shift element-dependent transcription through the zinc finger protein Gis1. EMBO J. 2000;19:2569–2579. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plecita-Hlavata L, Jezek J, Jezek P. Pro-oxidant mitochondrial matrix-targeted ubiquinone MitoQ10 acts as anti-oxidant at retarded electron transport or proton pumping within complex I. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1697–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon WW, Marbois BN, Faull KF, Clarke CF. 3-Hexaprenyl-4-hydrobenzoic acid forms a predominant intermediate pool in ubiquinone biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;320:305–314. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(95)90014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon WW, Do TQ, Marbois BN, Clarke CF. Sensitivity to treatment with polyunsaturated fatty acids is a general characteristic of the ubiquinone-deficient yeast coq mutants. Mol Aspects Med. 1997;18(Suppl):S121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(97)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinzii CM, Kattah AG, Naini A, Akman HO, Mootha VK, et al. Coenzyme Q deficiency and cerebellar ataxia associated with an aprataxin mutation. Neurology. 2005;64:539–541. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150588.75281.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinzii CM, DiMauro S, Hirano M. Human coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Neurochem Res. 2007a;32:723–727. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9190-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinzii CM, Hirano M, DiMauro S. CoQ10 deficiency diseases in adults. Mitochondrion. 2007b;7(suppl):S122–S126. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinzii CM, Lopez LC, Naini A, DiMauro S, Hirano M. Human CoQ10 deficiencies. Biofactors. 2008;32:113–118. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520320113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotig A, Appelkvist EL, Geromel V, Chretien D, Kadhom N, et al. Quinone-responsive multiple respiratory-chain dysfunction due to widespread coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Lancet. 2000;356:391–395. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugarli EI, Langer T. Mitochondrial quality control: a matter of life and death for neurons. EMBO J. 2012;31:1336–1349. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakumoto N, Mukai Y, Uchida K, Kouchi T, Kuwajima J, et al. A series of protein phosphatase gene disruptants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1999;15:1669–1679. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199911)15:15<1669::AID-YEA480>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salviati L, Sacconi S, Murer L, Zacchello G, Franceschini L, et al. Infantile encephalomyopathy and nephropathy with CoQ10 deficiency: a CoQ10-responsive condition. Neurology. 2005;65:606–608. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172859.55579.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salviati L, Trevisson E, Rodriguez Hernandez MA, Casarin A, Pertegato V, et al. Haploinsufficiency of COQ4 causes coenzyme Q10 deficiency. J Med Genet. 2012;49:187–191. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo GM. Glucose signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:253–282. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.253-282.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Ocaña C, Navas P, Crane FL, Córdoba F. Extracellular ascorbate stabilization as a result of transplasma electron transfer in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1995;27:597–603. doi: 10.1007/BF02111657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Ocaña C, Córdoba F, Crane FL, Clarke CF, Navas P. Coenzyme Q6 and iron reduction are responsible for the extracellular ascorbate stabilization at the plasma membrane of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8099–8105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz JR, Clarke CF. Characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ubiquinone-deficient mutants. Biofactors. 1999;9:121–129. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520090206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shults CW, Oakes D, Kieburtz K, Beal MF, Haas R, et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 in early Parkinson disease: evidence of slowing of the functional decline. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1541–1550. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.10.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippel CJ, Goewert RR, Slachman FN, Olson RE. The regulation of ubiquinone-6 biosynthesis by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RAJ, Murphy MP. Animal and human studies with the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1201:96–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack EC, Matson WR, Ferrante RJ. Evidence of oxidant damage in Huntington's disease: translational strategies using antioxidants. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1147:79–92. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staschke KA, Dey S, Zaborske JM, Palam LR, McClintick JN, et al. Integration of general amino acid control and target of rapamycin (TOR) regulatory pathways in nitrogen assimilation in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16893–16911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauche A, Krause-Buchholz U, Rödel G. Ubiquinone biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae the molecular organization of O-methylase Coq3p depends on Abc1p/Coq8p. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008;8:1263–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauskela JS. MitoQ – a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant. IDrugs. 2007;10:399–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen M, Lagniel G, Kristiansson E, Junot C, Nerman O, et al. Quantitative transcriptome, proteome, and sulfur metabolite profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae response to arsenite. Physiol Genomics. 2007;30:35–43. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00236.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran UC, Marbois B, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Jonassen T, Clarke CF. Complementation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae coq7 mutants by mitochondrial targeting of the Escherichia coli UbiF polypeptide: two functions of yeast Coq7 polypeptide in coenzyme Q biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16401–16409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513267200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troyano A, Fernández C, Sancho P, de Blas E, Aller P. Effect of glutathione depletion on antitumor drug toxicity (apoptosis and necrosis) in U-937 human promonocytic cells. The role of intracellular oxidation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47107–47115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104516200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turunen M, Olsson J, Dallner G. Metabolism and function of coenzyme Q. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1660:171–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter L, Nogueira V, Leverve X, Heitz MP, Bernardi P, Fontaine E. Three classes of ubiquinone analogs regulate the mitochondrial permeability transition pore through a common site. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29521–29527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie LX, Hsieh EJ, Watanabe S, Allan CM, Chen JY, et al. Expression of the human atypical kinase ADCK3 rescues coenzyme Q biosynthesis and phosphorylation of Coq polypeptides in yeast coq8mutants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1811:348–360. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie LX, Ozeir M, Tang JY, Chen JY, Jaquinod SK, et al. Over-expression of the Coq8 kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae coq null mutants allows for accumulation of diagnostic intermediates of the coenzyme Q6 biosynthetic pathway. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23571–23581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.360354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]