Abstract

Despite a burgeoning literature that documents numerous positive implications of forgiveness, scholars know very little about the potential negative implications of forgiveness. In particular, the tendency to express forgiveness may lead offenders to feel free to offend again by removing unwanted consequences for their behavior (e.g., anger, criticism, rejection, loneliness) that would otherwise discourage reoffending. Consistent with this possibility, the current longitudinal study of newlywed couples revealed a positive association between spouses’ reports of their tendencies to express forgiveness to their partners and those partners’ reports of psychological and physical aggression. Specifically, although spouses who reported being relatively more forgiving experienced psychological and physical aggression that remained stable over the first 4 years of marriage, spouses who reported being relatively less forgiving experienced declines in both forms of aggression over time. These findings join just a few others in demonstrating that forgiveness is not a panacea.

Keywords: forgiveness, marriage, recidivism, aggression, intimate partner violence

Although close romantic relationships are a source of some of life’s most gratifying experiences, they can also be the source of some of life’s most painful experiences. Partners may at times criticize one another, fail to adequately support one another, betray one another, or perpetrate psychological or physical abuse against one another. How should intimates respond to these and the other offenses to best prevent them from being repeated?

One way intimates can respond to the offenses that occur in their close relationships is to forgive their partners—that is, to experience a reduction in motivations toward revenge and avoidance and an increase in the motivation to continue the relationship (McCullough et al., 1998; McCullough, Worthington, & Rachal, 1997). And at least one theoretical perspective suggests that forgiveness should discourage partners from reoffending. Specifically, Gouldner (1960) described a universal norm of reciprocity that makes two demands: “(1) people should help those who have helped them, and (2) people should not injure those who have helped them” (p. 171). According to this norm, forgiven partners should feel obligated to reciprocate the prosocial act of forgiveness by not offending again in the future.

Nevertheless, a different theoretical perspective provides reason to expect the opposite—that forgiveness may permit partners to continue to offend. Specifically, theories of operant learning (e.g., Skinner, 1969) posit that people will continue to demonstrate existing patterns of behavior unless those behaviors are followed by unwanted consequences that motivate them to behave differently. Because unforgiven partners may experience numerous unwanted consequences for their offenses (e.g., anger, criticism, rejection, loneliness), they should be motivated to avoid repeating those offenses in the future. Because forgiveness may remove such unwanted consequences, in contrast, forgiven partners may continue offending.

The goal of the current research was to evaluate the implications of the tendency to express forgiveness to partners for changes in those partners’ reports of two particularly destructive behaviors—psychological and physical aggression. In pursuit of this goal, the following introduction is divided into four sections. The first section describes how theoretical and empirical work on the norm of reciprocity suggests that forgiveness should be associated with less reoffending. The second section describes how theoretical and empirical work on operant learning alternatively suggests that forgiveness should be associated with more reoffending. The third section argues that operant learning perspectives should provide a better account of the association between forgiveness and partner reoffending in close relationships than the norm of reciprocity because operant learning perspectives are better able to predict the pattern of domain-specific behaviors over substantial periods of time. Finally, the last section describes the current 4-year longitudinal study that tested the prediction that the tendency to express forgiveness to a partner is positively associated with changes in the extent to which that partner continues to perpetrate psychological and physical aggression over time.

Reciprocity and the Role of Forgiveness in Reoffending

Gouldner (1960) did not merely contend that the norm of reciprocity existed; he argued it was necessary to keep social systems stable. Without this norm, he argued, and without the consequential ability of relationship partners to hold one another accountable for a mutually beneficial exchange of resources, partners would not be able to protect themselves from exploitation by the other. Indeed, not only does the norm of reciprocity appear to operate in relationships based almost entirely on the exchange of resources, such as relationships between employees and their employers (Coyle-Shapiro & Kessler, 2002) and relationships between countries (e.g., Keohane, 1986), the norm of reciprocity appears to dictate the behavioral exchanges that occur in even the most communal relationships, such as marriage (for reviews, see Gottman, 1998; Van Yperen & Buunk, 1994). In a seminal study, for example, Gottman, Markman, and Notarius (1977) observed the sequential pattern of nonverbal behaviors exchanged between married partners engaged in problem-solving discussions. According to those observations, partners tended to reciprocate one another’s positive and negative behaviors. When one partner expressed positive affect, for example, the other partner tended to respond by also expressing positive affect. When one partner expressed negative affect, in contrast, the other partner tended to respond by also expressing negative affect.

Such patterns suggest that forgiven transgressors should be less likely to repeat their transgressions; to the extent that the victim of a transgression is able to forgive the transgressor, the norm of reciprocity dictates that the transgressor should respond with his or her own positive rather than negative behavior. Wallace, Exline, and Baumeister (2008) provided evidence consistent with this possibility. In two studies, participants were less likely to transgress against a stranger they believed had forgiven them for an offense than a stranger they believed had not forgiven them for an offense.

Fincham and Beach (2002) argued that forgiveness should have similar implications for the negative behaviors sometimes exchanged over the course of long-term close relationships. As they put it, “Either partner could likely act like a ‘circuit breaker,’ leading to a rapid de-escalation of the exchange. The ability of one spouse to forgive the partner for negative behavior, therefore, might lead to less negative behavior in the other.” Accordingly, Fincham and Beach went on to predict that “one person’s stylistic tendency to forgive should be the best antidote to the other’s use of psychological aggression” (pp. 241–242). Consistent with that prediction, their two cross-sectional studies of marriage revealed a negative association between spouses’ reports of their tendencies to forgive their partners and those partners’ reports of psychological aggression.

Nevertheless, the cross-sectional nature of those studies makes it impossible to draw causal conclusions regarding the association between spouses’ forgiveness and their partners’ negative behavior. Consistent with the norm of reciprocity, the negative associations between forgiveness and psychological aggression may have emerged because spouses’ forgiveness predicted less frequent psychological aggression by their partners. It is equally plausible, however, that less frequent psychological aggression perpetrated by those partners may have predicted a greater willingness of the spouses to forgive.

Operant Learning and the Role of Forgiveness in Reoffending

Theories of operant learning (e.g., Skinner, 1969) offer a contrasting view of the implications of forgiveness for reoffending. According to such theories, people are less likely to repeat existing patterns of behavior only if those behaviors are followed by unwanted outcomes. Accordingly, transgressors should continue to repeat their transgressions unless those transgressions are followed by unwanted consequences that motivate them to behave differently. Consistent with this idea, recent research indicates that negative behaviors, such as anger and criticism, motivate partners to change (McNulty & Russell, 2010; Overall, Fletcher, Simpson, & Sibley, 2009). Overall et al. (2009), for instance, reported that intimates’ tendencies to exhibit such direct negative behaviors predicted their partners’ self-reported willingness to change.

But forgiveness is antithetical to these behaviors (e.g., Cloke, 1993; Davenport, 1991; Denton & Martin, 1998; Enright & Human Development Study Group, 1991; Fitzgibbons, 1986; McCullough et al., 1997, 1998; North, 1987; see Lawler et al., 2003; Sells & Hargrave, 1998). McCullough et al. (1997) defined forgiveness as “the set of motivational changes whereby one becomes (a) decreasingly motivated to retaliate against an offending relationship partner, (b) decreasingly motivated to maintain estrangement from the offender, and (c) increasingly motivated by conciliation and goodwill for the offender” (pp. 321–322). Likewise, Enright and Human Development Study Group (1991) defined forgiveness as abandoning one’s right to negative emotions and behavioral responses directed at the transgressor. In support of such definitions, numerous studies indicate forgiveness is negatively associated with unwanted consequences for transgressors, such as anger (Lawler et al., 2005; Lin, Mack, Enright, Krahn, & Baskin, 2004) and isolation (Tsang, McCullough, & Fincham, 2006).

Accordingly, forgiven partners may not be motivated to discontinue their negative behaviors. Rather, the partners of forgiving individuals may learn that those individuals are unlikely to respond to their offenses with unwanted behaviors and, based on the principles of operant learning, continue to offend. The partners of less forgiving individuals, in contrast, may learn that those individuals are particularly likely to respond to their offenses with unwanted behaviors and thus stop offending.

Operant Learning Versus the Norm of Reciprocity

Which perspective provides the best description of the association between forgiveness and reoffending in close relationships? Recognizing the extent to which each theory can predict domain-specific behaviors over time may help answer this question. Research on the norm of reciprocity suggests reciprocations do not need to be domain specific. Rather, studies frequently demonstrate the norm of reciprocity by showing that participants will reciprocate one favor, such as being given a soft drink or a bottle of water, with a completely unrelated favor, such as delivering envelopes across campus or buying lottery tickets (e.g., Boster, Fediuk, & Kotowski, 2001; Burger, Horita, Kinoshita, Roberts, & Vera, 1997; Edlund, Sagarin, & Johnson, 2007; Regan, 1971). Accordingly, although close relationship partners can reciprocate forgiveness by refraining from future offenses, they can also reciprocate forgiveness by engaging in prosocial behaviors unrelated to the transgression. For example, although a husband who is forgiven by his wife for lying to her can reciprocate that forgiveness by telling her the truth in the future, he can also reciprocate that forgiveness by being extra supportive, giving her gifts, or being particularly affectionate.

And there is reason to expect forgiven partners to more frequently comply with the norm of reciprocity by engaging in prosocial behaviors unrelated to the transgression. Research indicates that people are most motivated to conform the norm of reciprocity immediately (Burger et al., 1997). Because forgiven partners may not immediately face motivations and opportunities to continue their offenses, however, they may not immediately have the opportunity to reciprocate forgiveness by refraining from such offenses. Accordingly, the motivation to immediately comply with the norm of reciprocity may lead forgiven partners to engage in prosocial behaviors unrelated to their transgressions. For example, because a husband who is forgiven by his wife for lying to her will likely not immediately face the motivation and opportunity to lie to her again, he will likely not be able to immediately reciprocate her forgiveness by resisting the temptation to lie. Instead, the motivation to immediately comply with the norm of reciprocity may lead him to engage in prosocial behaviors unrelated to the lie—such as being extra supportive, giving her gifts, or being particularly affectionate. Indeed, the participants who were less likely to reoffend strangers in the two studies by Wallace et al. (2008) faced the opportunity to reciprocate forgiveness immediately after they were forgiven. In ongoing close relationships in which partners can reciprocate forgiveness through numerous prosocial behaviors that may be unrelated to the transgression, however, the norm of reciprocity may not best predict the link between forgiveness and the extent to which partners will engage in the same transgression again.

Instead, given that principles of operant learning were specifically formulated to describe the relationship between the consequences of a specific behavior and future occurrences of that same behavior, such principles should provide a better description of the link between forgiveness and reoffending. Specifically, whereas partners who tend to be forgiven for their offenses should learn to anticipate being forgiven for those same offenses in the future, partners who tend to not be forgiven for their offenses should learn to anticipate not being forgiven for those same offenses in the future. In turn, those learned behavioral contingencies should predict the extent to which partners repeat their negative behaviors.

Although no studies have directly examined the link between forgiveness and changes in the same negative behavior over time, several studies are consistent with the predictions derived from theories of operant learning. For instance, Luchies, Finkel, McNulty, and Kumashiro (2010, Study 1) reported that more forgiving spouses experienced decreases in self-respect over time to the extent that they were married to less agreeable partners. Similarly McNulty (2008a) reported that more forgiving spouses experienced increases in the severity of their marital problems over time to the extent that they were married to partners who demonstrated relatively high levels of negative verbal behavior. Consistent with predictions derived from theories of operant learning, perhaps forgiving relatively disagreeable or negative partners led to decreased self-respect and increased problem severity in those studies because it failed to discourage those partners from continuing their negative behaviors. Indeed, McNulty (2010a) recently used a daily diary study to show that spouses were more likely to report that their partners had transgressed against them on days after they reported having forgiven those partners than days after they reported having not forgiven those partners. Nevertheless, given that spouses in that study reported only whether their partners engaged in a “negative behavior” each day and not what that negative behavior was, it is unclear whether forgiveness predicted a general tendency to behave negatively the next day or a tendency to repeat the same offense that was forgiven the previous day.

Overview of the Current Study

The current longitudinal study of newlywed couples evaluated the link between spouses’ reports of their tendencies to express forgiveness to their partners and changes in the same behavior over time—psychological and physical aggression. At baseline, both members of the couple reported their tendencies to express forgiveness to one another and the extent to which they had perpetrated acts of psychological and physical aggression against one another. Then, both members of the couple again reported their psychological and physical aggression three more times over the course of 4 years. Analyses tested the hypothesis that spouses’ tendencies to express forgiveness to their partners would be positively associated with changes in those partners’ reports of aggression over time.

Method

Participants

Participants were 72 first-married couples participating in a broader study of marital development.1 All participants were first assessed within 6 months after the wedding (M = 3.2, SD = 1.6). Participants were recruited from communities in and around north-central Ohio using two methods. The first was to place advertisements in community newspapers and bridal shops offering payment to couples willing to participate in a longitudinal study of newlyweds. The second was to send invitations to eligible couples who had completed marriage license applications in counties near the study location. All couples responding to either solicitation were screened for eligibility in an initial telephone interview. Inclusion required that (a) this was the first marriage for each partner, (b) the couple had been married less than 6 months, (c) each partner was at least 18 years of age, and (d) each partner spoke English and had completed at least 10 years of education (to ensure comprehension of the questionnaires).

On average, husbands were 24.9 years (SD = 4.4) old and had completed 14.2 years (SD = 2.5) of education. Of husbands, 74% were employed full-time and 11% were full-time students. The median income range identified by husbands was $15,001 to $20,000 per year. Of husbands, 93% were Caucasian, 4% identified as African American, and 3% identified as other. On average, wives were 23.5 years (SD = 3.8) old and had completed 14.7 years (SD = 2.2) of education. Of wives, 49% were employed full-time and 26% were full-time students. The median income range identified by wives was $10,001 to $15,000 per year. Of wives, 96% were Caucasian and 4% were African American.

Procedure

As part of the broader aims of the study, couples attended a laboratory session at baseline. Before that session, they were mailed a packet of questionnaires to complete at home and bring with them to their appointment. This packet included a consent form approved by the local human subjects review board, self-report measures of forgiveness, physical and psychological aggression, and various individual difference measures, and a letter instructing participants to complete all questionnaires independently of one another and to bring their completed questionnaires to their upcoming laboratory session.

At approximately 6- to 8-month intervals subsequent to the initial assessment, couples were recontacted by phone or email and again mailed a packet of questionnaires that contained the same measure of psychological and physical aggression, along with a postage-paid return envelope and a letter of instruction reminding couples to complete forms independently of one another. After completing each phase, couples were mailed a $50 check for participating. This procedure was used at every 6- to 8-month interval with the exception that Wave 5 occurred approximately 12 months after Wave 4. Given that the aggression measure asked spouses to report the aggression they had perpetrated in the past year, only the data collected at every other 6-month assessment were analyzed here. Thus, the current analyses are based on up to four assessments that spanned the first 4 years of marriage.

Materials

Tendency to express forgiveness

At Time 1, participants reported their tendencies to express forgiveness to their marital partner by completing a measure modeled after the Transgression Narrative Test of Forgivingness (TNTF; Berry et al., 2001). Specifically, this measure presented spouses with detailed descriptions of five hypothetical marital transgressions that varied in severity (e.g., the partner snapped at and insulted the spouse) and asked them to report whether they would “express forgiveness” (1 = definitely no, 7 = definitely yes). Spouses’ responses to these five items were averaged to create an index that captured their tendency to express forgiveness that ranged from 1 to 7. Internal consistency was adequate (husbands’ coefficient α = .81, wives’ coefficient α = .84).

Although novel, this measure of forgiveness is theoretically appropriate for at least three reasons. First, it is expressions of forgiveness, not necessarily feelings of forgiveness, that should remove unwanted consequences of partners’ offenses and thus increase the chances that those partners will reoffend.2 Second, it is a general tendency to express forgiveness, rather than just one or two specific acts of forgiveness, that should shape partners learning contingencies over substantial amounts of time, like the first several years of marriage. Finally, it is the tendency to express forgiveness to the partner, rather than the tendency to forgive others generally, that should be most directly related to partners’ subsequent behaviors. Consistent with the idea that this measure distinguished between such tendencies, although it was correlated with a more general measure of the tendency to forgive, Brown’s (2003) Tendency to Forgive Scale (for wives, r = .39, p < .01; for husbands, r = .28, p < .05), supporting its construct validity, the modest size of the correlations indicates that people’s tendencies to express forgiveness to their romantic partners can differ from their tendencies to forgive generally.

Psychological and physical aggression

At Time 1 and all yearly follow-ups, participants reported how frequently they had perpetrated six psychologically aggressive behaviors (insulted or swore at the spouse; sulked or refused to talk about an issue; stomped out of the room, house, or yard; did or saying something to spite the other, threatened to hit or throw something; and threw, smashed, hit, or kicked something) and eight physically aggressive behaviors (threw something at spouse, pushed, grabbed, or shoved the spouse, slapped the spouse, kicked, bit or hit the spouse with a fist, hit or tried to hit the spouse with something, beat up the spouse, threatened to use a knife or gun, and used a knife or gun) from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979) during arguments over the past year on a 4-point scale from 0 (never) to 3 (more than twice). Reports were summed at each wave of data collection.

Covariates

Several qualities likely to be confounded with the tendency to express forgiveness to the partner and partner aggression were assessed at Time 1 to be ruled out as third variable explanations. Marital satisfaction was assessed using the 7-item Quality Marriage Index (Norton, 1983; range = 6–45, husbands’ and wives’ α = .93). Self-esteem was assessed using the 10-item Rosenberg (1965) Self-Esteem Scale (range = 1–4, husbands’ α = .87, wives’ α = .84). Quality of alternatives outside the relationship was assessed using a 5-item scale that assessed spouse’s perceived abilities to leave the relationship (Frye, McNulty, & Karney, 2008; range = 1–7, husbands’ α = .77, wives’ α = .79). Attachment insecurity was assessed using the 36-item Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998) (for anxiety, range = 1–7, husbands’ α = .91, wives’ α = .90; for avoidance, range = 1–7, husbands’ α = .91, wives’ α = .88). Agreeableness and neuroticism were assessed using the 10-item Agreeableness and Neuroticism subscales of the Big Five Personality Inventory short-form developed by Goldberg (1999; for agreeableness, range = 1–5, husbands’ α = .74, wives’ α = .83; for neuroticism, range = 1–5, husbands’ α = .90, wives’ α = .88).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics of the tendency to express forgiveness and the covariates are reported in Table 1. As the table reveals, both husbands and wives tended to report being relatively likely to express forgiveness to their partners, on average. Nevertheless, the standard deviations of those reports indicate that some spouses were more likely to express forgiveness to their partners than others. Also, husbands and wives reported relatively high levels of marital satisfaction and self-esteem, relatively few better alternatives outside the relationship, relatively low levels of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance, relatively high levels of agreeableness, and neuroticism scores that were near the midpoint. Nevertheless, the standard deviations indicated substantial variability in those variables as well. Notably, husbands reported higher levels of attachment avoidance than did wives, t(70) = 2.17, p < .05, lower levels of agreeableness than did wives, t(71) = 6.99, p < .001, and lower levels of neuroticism than did wives, t(71) = 5.04, p < .001

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Husbands

|

Wives

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Tendency to express forgiveness | 5.19 | 1.28 | 5.04 | 1.24 |

| Marital satisfaction | 40.97 | 4.81 | 41.74 | 4.96 |

| Self-esteem | 3.40 | 0.51 | 3.45 | 0.45 |

| Quality of alternatives | 1.89 | 1.44 | 2.34 | 1.50 |

| Attachment anxiety | 2.14 | 0.97 | 2.02 | 0.85 |

| Attachment avoidance | 2.07 | 0.88 | 1.83 | 0.68 |

| Agreeableness | 3.79 | 0.51 | 4.34 | 0.48 |

| Neuroticism | 2.37 | 0.83 | 3.02 | 0.77 |

Correlations between the tendency to express forgiveness and the covariates are reported in Table 2. Several results are worth highlighting. First, the tendency to express forgiveness was positively associated with own marital satisfaction among both husbands and wives. Second, the tendency to express forgiveness was negatively associated with neuroticism and marginally negatively associated with quality of alternatives among husbands. Third, the tendency to express forgiveness was positively associated with agreeableness and marginally positively associated with self-esteem among wives. Fourth, associations between the tendency to express forgiveness and both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance failed to reach significance among either husbands or wives. Finally, husbands’ and wives’ tendencies to express forgiveness to one another were positively associated.

Table 2.

Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Tendency to express forgiveness | .32** | .26* | .23† | −.13 | −.03 | .02 | .37** | −.11 |

| 2. Marital satisfaction | .25* | .41** | .47** | −.23† | −.32** | −.39** | .36** | −.29* |

| 3. Self-esteem | .01 | .20† | .27* | −.08 | −.35** | −.33** | .32** | −.34** |

| 4. Quality of alternatives | −.21† | −.15 | −.05 | .39** | −.08 | −.00 | .12 | .12 |

| 5. Attachment anxiety | −.07 | −.34** | −.21† | .05 | .20† | .56** | −.05 | .52** |

| 6. Attachment avoidance | −.08 | −.17 | −.30* | .00 | .61** | .29* | −.11 | .42** |

| 7. Agreeableness | .17 | .22† | .31** | .05 | −.13 | −.14 | .01 | −.13 |

| 8. Neuroticism | −.23* | −.30* | −.18 | −.05 | .30* | .14 | .10 | .05 |

Note: Wives’ correlations appear above the diagonal, husbands’ correlations appear below the diagonal, and correlations between husbands and wives appear on the diagonal in bold.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Describing the Trajectory of Psychological and Physical Aggression

Average levels of husbands’ and wives’ psychological and physical aggression at each yearly assessment are reported in Table 3. As Table 3 reveals, partners reported moderate levels of psychological aggression on average that appeared to diminish over time and lower levels of physical aggression on average that also appeared to diminish over time. To assess such within-person change, growth curve analyses (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1987) described trajectories of partners’ psychological and physical aggression using the Hierarchical Linear Modeling 6.08 computer program (Bryk, Raudenbush, & Congdon, 2004). Specifically, partners’ reports of psychological and physical aggression were each regressed onto time of assessment, defined as years since baseline, using the following Level 1 equation:

| (1) |

where Ytp is the psychological or physical aggression of partner p at Time t; π0p is the psychological or physical aggression of partner p at Time 1 (i.e., the initial aggression for partner p), π1p is the rate of linear change in psychological or physical aggression of partner p, and etp is the residual variance in repeated measurements for partner p. This model can be understood as a within-subjects regression of partners’ psychological or physical aggression onto time of assessment, where the autocorrelation from repeated assessments was controlled in the second level of the analysis and the shared variance between husbands’ and wives’ data was controlled in a third level of the analysis. Notably, because trajectories could be computed for all spouses who participated in at least one assessment, these analyses were based on all 144 individuals.

Table 3.

Mean Psychological and Physical Aggression Scores Across Waves of Measurement for Husbands and Wives

| Time 1 | Time 3 | Time 5 | Time 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological aggression | ||||

| Husbands | ||||

| M | 6.22 | 5.42 | 5.02 | 5.05 |

| SD | 4.77 | 4.31 | 4.05 | 4.56 |

| N | 72 | 56 | 53 | 37 |

| Wives | ||||

| M | 7.15 | 6.43 | 6.23 | 5.63 |

| SD | 5.08 | 4.36 | 4.51 | 4.98 |

| N | 72 | 60 | 56 | 37 |

| Physical aggression | ||||

| Husbands | ||||

| M | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.25 | 0.30 |

| SD | 0.91 | 2.31 | 0.68 | 1.05 |

| N | 72 | 56 | 53 | 37 |

| Wives | ||||

| M | 1.24 | 0.70 | 0.82 | 0.76 |

| SD | 2.59 | 2.41 | 2.14 | 2.41 |

| N | 72 | 60 | 56 | 37 |

Mean estimates and standard deviations of the growth curve parameters estimated by Equation 1 and t-statistics that test whether those estimates differed from 0 are presented in Table 4. As the table reveals, the intercepts produced by those analyses revealed that partners reported perpetrating almost seven acts of psychological aggression in the beginning of the study on average and just less than one act of physical aggression in the beginning of the study on average. Notably, tests of each Sex × Time interaction revealed that wives reported perpetrating marginally more psychological aggression than husbands, B = −0.46, SE = 0.27, t(142) = −1.73, p = .09, and significantly more physical aggression than husbands, B = −0.32, SE = 0.11, t(142) = −2.84, p < .01, in the beginning of the study. The slopes produced by these analyses revealed that reports of both psychological and physical aggression tended to decrease over the course of the study, on average. Though husbands and wives did not differ in the extent to which their reports of psychological aggression changed over the course of the study, B = 0.05, SE = 0.08, t(142) = 0.64, p > .50, wives reported significantly stronger decreases in physical aggression over time, B = 0.05, SE = 0.24, t(142) = 2.05, p < .05.

Table 4.

Trajectories of Psychological and Physical Aggression

| B | SD | t | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological aggression | |||

| Intercept | 6.65 | 2.72 | 13.79*** |

| Slope | −0.29 | 0.41 | −2.36* |

| Physical aggression | |||

| Intercept | 0.84 | 1.22 | 4.09*** |

| Slope | −0.09 | 0.01 | −2.12* |

Note: df = 71.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Does the tendency to express forgiveness account for changes in partner aggression over time?

The hypothesis that the tendency to express forgiveness would be positively associated with changes in partner aggression was tested by regressing both the intercepts and slopes of each form of partner aggression estimated in Equation 1 onto spouses’ reports of their own tendencies to express forgiveness in a second level of the analysis. The nonindependence of husbands’ and wives’ data was controlled in the third level of the model. Intercept and slope estimates were allowed to vary randomly across spouses and couples. Notably, given positive skew in the distribution of the physical aggression data, models accounting for the trajectory of physical aggression specified a Poisson distribution for that variable.

Results regarding the association between the tendency to express forgiveness and the initial levels of partner aggression (i.e., the intercepts of the trajectories estimated in Equation 1) are reported in the top portion of each section of Table 5. Consistent with prior research (Fincham & Beach, 2002), the tendency to express forgiveness was marginally negatively associated with initial levels of psychological aggression and significantly negatively associated with initial levels of physical aggression, indicating that, not surprisingly, spouses were less likely to express forgiveness to more psychologically and physically aggressive partners.

Table 5.

Associations Between the Tendency to Express Forgiveness and the Trajectories of Psychological and Physical Aggression

| B | SE | Effect size r | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological aggression | |||

| Intercepts | |||

| Constant | 6.66 | 0.46 | .86*** |

| Tendency to express forgiveness | −0.11 | 0.06 | −.14† |

| Slopes | |||

| Constant | −3.04−1 | 1.16−1 | −.30* |

| Tendency to express forgiveness | 0.38−1 | 0.16−1 | .19* |

| Physical aggression | |||

| Intercepts | |||

| Constant | 7.47−1a | 1.97−1 | .17 |

| Tendency to express forgiveness | −0.68−1 | 0.25−1 | −.22** |

| Slopes | |||

| Constant | −1.08−1 | 0.29−1 | −.41** |

| Tendency to express forgiveness | 0.24−1 | 0.04−1 | .49*** |

Note: For constant, df = 71; for tendency to express forgiveness, df = 142.

Exp(B).

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Results regarding the association between the tendency to express forgiveness and changes in partner aggression (i.e., the slopes of the trajectories estimated in Equation 1) are reported in the bottom portions of each section of Table 5. Consistent with predictions, the tendency to express forgiveness was positively associated with changes in both forms of aggression. Importantly, tests of each Sex × Forgiveness × Time interaction revealed that neither association varied by participant sex.

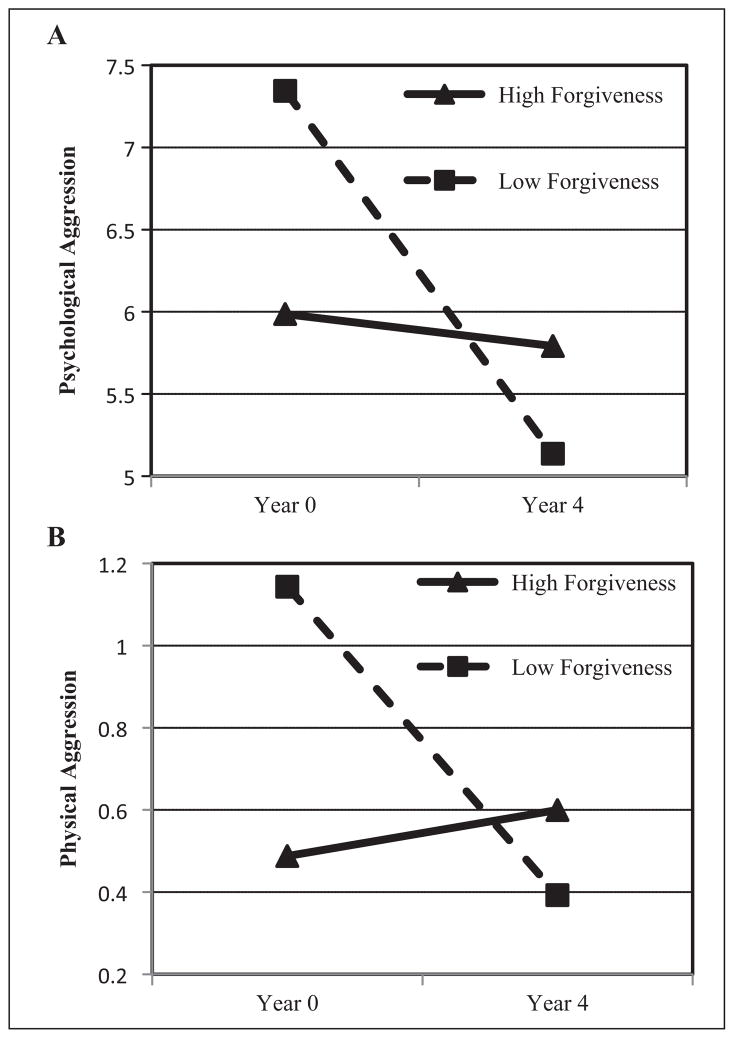

The predicted trajectories of each form of partners’ aggression were plotted for spouses 1 SD above and below the mean of the tendency to express forgiveness. Those plots are depicted in Figure 1. As revealed in Panel A, the partners of spouses who reported being more likely to express forgiveness reported levels of psychological aggression that appeared to remain relatively stable over the 4-year course of the study, whereas the partners of spouses who reported being less likely to express forgiveness reported levels of psychological aggression that appeared to decrease substantially over the course of the study. Simple slopes analyses confirmed these appearances. Specifically, the partners of spouses who reported being 1 SD more likely to express forgiveness than the mean reported levels of psychological aggression that remained stable over the course the study, B = −0.06, SE = 0.16, t(71) = −0.40, ns, whereas the partners of spouses who reported being 1 SD less likely to express forgiveness than the mean reported levels of psychological aggression that declined over the course of the study, B = −0.54, SE = 0.16, t(71) = −3.32, p < .01.

Figure 1.

Tendencies to express forgiveness and trajectories of partner aggression (A and B)

Likewise, as revealed in Panel B, the partners of spouses who reported being more likely to express forgiveness reported levels of physical aggression that appeared to remain relatively stable over the 4-year course of the study, whereas the partners of spouses who reported being less likely to express forgiveness reported levels of physical aggression that appeared to decrease substantially over the course of the study. Simple slopes analyses confirmed these appearances as well. Specifically, the partners of spouses who reported being 1 SD more likely to express forgiveness than the mean reported levels of physical aggression that remained stable over the course the study, B = 0.04, SE = 0.03, t(71) = 0.99, ns, whereas the partners of spouses who reported being 1 SD less likely to express forgiveness than the mean reported levels of physical aggression that declined over the course of the study, B = −0.23, SE = 0.07, t(71) = −3.15, p < .01.

Did the associations between the tendency to express forgiveness and changes in psychological and physical aggression emerge because of regression to the mean?

Given that the partners of spouses who reported being more likely to express forgiveness reported higher (or marginally higher) levels of each form of aggression initially, it is possible that associations between the tendency to express forgiveness and changes in each form aggression emerged because the partners of spouses who reported being less likely to express forgiveness simply had more room to demonstrate decreases in aggression—that is, regression to the mean. I conducted a set of analyses to help rule out this possibility. Specifically, I again regressed both the intercepts and slopes of each form partner aggression estimated in Equation 1 onto spouses’ reports of their tendencies to express forgiveness to their partners in a second level of the analysis, but this time I also entered the baseline levels of each form of aggression to account for variance in changes in that form of aggression in that second level of the analysis. Notably, I also removed those baseline reports from the Level 1 analysis that estimated the each growth curve (to avoid redundancy). If the associations that emerged between the tendency to express forgiveness and changes in each form of aggression were the result of initial levels of that form of aggression, controlling for initial levels of aggression should eliminate those associations. It did not. The tendency to express forgiveness to the partner remained positively associated with changes in each form of partner aggression even after initial levels of that form of aggression were removed from the trajectory and instead controlled in the second level of the analysis, for psychological aggression, B = 5.59−2, SE = 2.74−2, t(141) = 2.04, p < .05; for physical aggression, B = 3.25−2, SE = 1.02−2, t(141) = 3.19, p < .01.

Did the associations between the tendency to express forgiveness and changes in psychological and physical aggression emerge because of differential attrition?

Given that only 37 of the 72 couples participated in the last phase of data collection analyzed here, it is also possible that the associations between the tendency to express forgiveness and changes in partner aggression emerged because of differential attrition. Indeed, although direct comparisons revealed that husbands who completed the last assessment did not differ from husbands who did not complete the last assessment in their tendencies to forgive, their initial experiences of partner psychological aggression or physical aggression, or changes in their experiences of partners psychological aggression, such husbands did experience more stable physical aggression from their partners than husbands who did not complete the last assessment, t(140) = 3.97, p < .001. Likewise, although direct comparisons revealed that wives who completed the last assessment did not differ from wives who did not complete the last assessment in their initial experiences of partner psychological aggression or physical aggression or changes in their experiences of their partners’ psychological aggression, such wives did experience more stable physical aggression from their partners, t(140) = 3.56, p < .01, and were marginally more forgiving than were wives who did not complete the last assessment, t(70) = 1.94, p = .06. Accordingly, I examined whether or not these differences accounted for the association between the tendency to express forgiveness and changes in psychological and physical aggression. Specifically, I created a dummy code that indicated whether or not each partner completed the final assessment and reestimated the associations between the tendency to express forgiveness and changes in aggression while controlling that variable. The tendency to express forgiveness remained positively associated with changes in both forms of partners’ aggression, controlling for whether spouses completed the final assessment, for psychological aggression, B = 3.70−2, SE = 1.64−2, t(72) = 2.25, p < .05; for physical aggression, B = 2.13−2, SE = 0.47−2, t(141) = 4.50, p < .001.3

Did the associations between the tendency to express forgiveness and changes in psychological and physical aggression emerge because of third variables?

Finally, it is also possible that several other third variables correlated with both the tendency to express forgiveness and partner aggression account for the association between the tendency to express forgiveness and changes in partner aggression. Thus, I conducted one final set of analyses to help rule out this possibility. Specifically, I again regressed both the intercepts and slopes of each form partner aggression estimated in Equation 1 onto spouses’ reports of their tendencies to express forgiveness to their partners in a second level of the analysis, but this time I also entered (a) participant sex, (b) own marital satisfaction, (c) own self-esteem, (d) own reported quality of alternatives outside the relationship, (e) own agreeableness, (f) own neuroticism, (g) own attachment anxiety, and (h) own attachment avoidance. Spouses’ self-reported tendencies to express forgiveness continued to predict changes in each form of partner aggression even after all these variables were controlled, for psychological aggression, B = 3.61−2, SE = 1.76−2, t(134) = 2.05, p < .05; for physical aggression, B = 3.23−2, SE = 0.41−2, t(134) = 7.97, p < .001.

Discussion

Existing theoretical perspectives provide competing predictions regarding the implications of forgiveness for the extent to which partners will continue their negative behaviors. Theories of reciprocity (e.g., Buunk & Schaufeli, 1999; Gouldner, 1960) suggest that forgiven partners may be less likely to reoffend because they should feel obligated to reciprocate forgivers’ benevolence. Theories of operant learning (e.g., Skinner, 1969), in contrast, suggest that forgiven partners may continue to reoffend because forgiveness should remove unwanted consequences of their transgressions that would otherwise motivate them to refrain from repeating their offenses.

Given that the norm of reciprocity may best explain the association between forgiveness and reoffending when people are faced with immediate opportunities to reoffend (see Wallace et al., 2008) whereas operant learning perspectives should provide a better description of the sequence of domain-specific behaviors that emerge over the course of long-term close relationships, the current research tested the prediction that spouses’ tendencies to express forgiveness to their partners would be positively associated with changes in those partners’ psychological and physical aggression over time. Results were consistent with this prediction. Specifically, the partners of spouses who reported being more likely to express forgiveness to them reported perpetrating acts of psychological and physical aggression against those partners that remained stable over the first 4 years of marriage, whereas the partners of spouses who reported being less likely to express forgiveness to them reported acts of psychological and physical aggression that decreased over those 4 years. Notably, the positive association between spouses’ tendencies to express forgiveness and changes in their partners’ aggression (a) emerged in analyses of both psychological and physical aggression, (b) did not vary across husbands and wives, (c) was not the result of initial levels of aggression, (d) emerged controlling for any variables associated with differential attrition, and (e) emerged controlling for participant sex, relationship satisfaction, self-esteem, the quality of alternatives outside the relationship, attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, agreeableness, and neuroticism. In other words, the positive association between the tendency to express forgiveness to the partner and changes in that partner’s aggression appears to be quite robust.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The finding that the tendency to express more forgiveness predicted stable levels of both psychological and physical aggression over time whereas the tendency to express less forgiveness predicted decreases in both forms of aggression has important theoretical implications. Specifically, it challenges numerous long-standing theories of relationships that suggest negative behaviors should be avoided because they lead to immediate negative evaluations of the relationship (e.g., Gottman, 1979; Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Rusbult, 1980, 1983; Rusbult, Verette, Whitney, Slovik, & Lipkus, 1991; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959; Walster, Walster, & Berscheid, 1978; Wills, Weiss, & Patterson, 1974). What may be missing from such theories is the idea that although negative behaviors may indeed be unsatisfying initially, they can motivate necessary changes in the partner. For instance, Overall et al. (2009) demonstrated that direct negative statements to a relationship partner, which tend to be associated with more negative evaluations of the relationship immediately (for a review, see Heyman, 2001), predicted positive change in the partner 1 year later. Similarly, McNulty and Russell (2010) reported that, among spouses facing more severe relationship problems, the tendency to exhibit more direct negative behaviors was associated with lessened problem severity and more stable relationship satisfaction over time than the tendency to refrain from such behaviors. In line with such findings, a growing body of research indicates that a variety of processes that are associated with higher levels of satisfaction initially, such as positive illusions, positive attributions, positive expectancies, and, in the current research, forgiveness, can harm relationships over time if they allow serious problems to go unaddressed and unresolved (e.g., McNulty & Karney, 2004; McNulty, O’Mara, & Karney, 2008; for a review, see McNulty, 2010b). Accordingly, theories of relationship maintenance may benefit from revisions that consider both the long- and short-term implications of various processes.

The current findings have important practical implications as well. Specifically, they question the net benefits of interventions designed to promote forgiveness. Although such interventions tend to promote feeling forgiveness rather than expressing forgiveness to the partner (for an example, see Gordon, Baucom, & Snyder, 2005), clients who learn to feel forgiveness may be more likely to express those feelings to their partners, either directly or indirectly. Accordingly, although interventions that promote forgiveness have proved successful in raising self-esteem and positive affect (Lundahl, Taylor, Stevenson, & Roberts, 2008), the current findings suggest that such benefits may come at an important cost—the continued risk of partner transgressions such as psychological and physical aggression. Accordingly, clients may benefit to the extent that practitioners weigh the potential benefits of forgiveness against this potential cost of expressing forgiveness before promoting forgiveness in ongoing relationships. Ultimately, whether or not it is beneficial to forgive a partner may depend on the frequency and/or severity of that partner’s transgression(s). Specifically, forgiving infrequent or minor offenses may be advisable because any repeat occurrences of such offenses should also be infrequent or minor and thus not outweigh the benefits of forgiveness. Nevertheless, forgiving frequent or major offenses, such as frequent verbal abuse (see McNulty, 2008a) or any physical abuse (see Gordon, Burton, & Porter, 2004), may be less advisable because any repeat occurrences of such frequent or severe offenses may damage the victim or relationship and thus outweigh the benefits of forgiveness.

Directions for Future Research

The current research also suggests several avenues for future research. First, although the measure of forgiveness used here—spouses’ reports of their tendencies to express forgiveness to their partners—provided a theoretically appropriate way to test the current hypothesis derived from theories of operant learning, future research may benefit by examining whether or not other measures and definitions of forgiveness demonstrate similar implications for partner behavior. For example, although people’s tendencies to express forgiveness to their partners appear to predict the extent to which those partners will reoffend, it remains unknown whether feeling forgiveness but not expressing that forgiveness to the partner has similar implications. On one hand, it may be that experiences of forgiveness that remain unknown to the partner do not remove unwanted consequences for that partner and thus do not predict reoffending. Alternatively, it may be that feeling forgiveness indirectly removes unwanted consequences for the partner and thus also predicts reoffending. Indeed, various conceptualizations of forgiveness (e.g., Fincham & Beach, 2001; McCullough et al., 1997, 1998) suggest forgiveness is a tendency to become more motivated to approach the transgressor and less motivated to avoid the transgressor. Accordingly, even forgiveness that is not directly communicated to the partner may predict reoffending by promoting contact and thus removing unwanted isolation or loneliness.

Likewise, future research may benefit by examining the implications of other definitions of forgiveness. The current study left definitions of forgiveness up to the participants. Although laypersons’ definitions of forgiveness deviate somewhat from the definitions used by researchers and practitioners (see Kearns & Fincham, 2004), laypersons are the ones who decode one another’s expressions of forgiveness. That is, when a wife tells her husband that she forgives him, he will use his definition of forgiveness, not researchers’ definitions of forgiveness, to understand what she means and behave accordingly. Thus, the current measure was an ecologically valid way to test the current hypothesis. However, forgiveness as defined by forgiveness scholars—for example, forgiveness that is distinct from forgetting or condoning (Gordon et al., 2005) or forgiveness that is distinct from reconciliation (Fincham & Beach, 2001)—may not have the same implications for recidivism. Knowing whether different definitions of forgiveness have similar or different effects on recidivism will allow researchers to know whether and what particular components of forgiveness as defined by laypersons are responsible for the positive association between expressing forgiveness and reoffending that emerged here.

Finally, future research may benefit by identifying moderators of the main effects that emerged here. Although the tendency to express forgiveness was positively associated with partners’ negative behavior in this study on average, contextual models of relationships (e.g., Bradbury & Fincham, 1991) and recent research (see McNulty, 2010b) suggest that such effects may vary according to important contextual variables. Indeed, although McNulty (2008a) reported that forgiveness was associated with less satisfaction and more severe problems over time among spouses married to partners who behaved negatively relatively frequently, he also reported that forgiveness was associated with greater satisfaction and fewer problems over time among spouses married to partners who behaved negatively only rarely. Similarly, although Luchies et al. (2010) reported that forgiveness was associated with decreased self-respect among intimates whose partners did not make amends or were disagreeable, they also reported that forgiveness was associated with more self-respect among intimates whose partners made amends or were agreeable. Perhaps these or other qualities of offenders moderate the main effects of forgiveness on partner behavior that emerged here, such that forgiveness is unrelated or even negatively related to reoffending among more agreeable and less negative partners.

Strengths and Limitations

Several strengths of the current research enhance confidence in the conclusions drawn here. First, the current study demonstrated the association between one partner’s reports of forgiveness and changes in the other partner’s reports of psychological aggression, providing confidence that the associations did not emerge as the result of common method or self-presentational variance. Second, although the average rate of retention in most longitudinal research of marriage is 69% (Karney & Bradbury, 1995), the current longitudinal analyses were based 100% of the original sample and emerged controlling for whether or not spouses completed the fourth and final assessment. Third, the current study accounted for change in two forms of a theoretically and practically important behavior, aggression, over the first several years of meaningful relationships, marriages, providing confidence that the results reported here are ecologically valid.

Nevertheless, several qualities of this research limit the extent to which some conclusions can be drawn with confidence until these findings can be extended. First, although the longitudinal nature of the data helped eliminate ambiguity regarding the causal direction of the relationships that emerged, and although analyses controlled for the influence of several third variables (i.e., relationship satisfaction, self-esteem, quality of alternatives outside the relationship, attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, agreeableness, and neuroticism), it is possible that other third variables not assessed and controlled here may account for these findings. Ultimately, experimental studies that manipulate expressions of forgiveness and assess partner negative behavior will be most convincing in demonstrating the causal effect of forgiveness on partner reoffending. Second, although assessing newlyweds allowed the opportunity to assess broader variability in change over time while at the same time minimizing differences in relationship duration and age, it also minimized the extent to which these findings can be generalized to other relevant types of relationships such as dating couples, more established marriages, friendships, parent–child relationships, and employee–employer relationships. It is possible that these findings are particularly likely to emerge in new marriages as couples negotiate patterns of behavior that may be just developing. Future research may benefit by examining whether expressing forgiveness has similar implications in other types of relationships. Finally, the couples assessed in this study were rather similar in age, race, ethnicity, cultural background, and religious affiliation. Although the current studies did demonstrate that the predicted effect did not vary across one important demographic factor, sex, future research may benefit by examining whether the association between the tendency to express forgiveness and recidivism varies across other demographic factors in more varied samples.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Preparation for this article was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Development Grant RHD058314A awarded to James K. McNulty.

Footnotes

Although data from the sample described here are described in other articles (Baker & McNulty, 2010, in press; Fisher & McNulty, 2008; Frye, McNulty, & Karney, 2008; Little, McNulty, & Russell, 2010; Luchies, Finkel, McNulty, & Kumashiro, 2010; McNulty, 2008a, 2008b; McNulty & Fisher, 2008; McNulty & Hellmuth, 2008; McNulty & Russell, 2010; Russell & McNulty, 2011), there has been little overlap between the variables examined in these prior articles and the variables examined here. The two exceptions are that the five items that assessed participants’ tendencies to express forgiveness at baseline used in the present article were used in conjunction with five other items to that assessed participants tendencies to feel forgiveness to (a) predict changes in satisfaction and problems over 2 years in McNulty (2008a) and (b) predict changes in self-respect over 4.5 years in Luchies et al. (2010). However, the current article investigates the association between these five items and changes in a conceptually distinct variable—partner psychological aggression. Furthermore, the findings reported in the current article are independent of the findings reported in those studies in that controlling for those outcomes does not change the results reported here. Notably, the decision to use only the five items that assessed participants’ tendency to express forgiveness and not the five items that assessed participants’ tendencies to feel forgiveness was made a priori based on the belief that expressions of forgiveness should be most apparent to the partner and thus most directly related to partners’ tendencies to reoffend according to the theoretical perspectives that guided the current hypothesis.

See Note 1.

I also conducted an analysis using only the data from the 37 couples who participated during the final assessment. The tendency to express forgiveness was positively associated with changes in both psychological and physical aggression in this subsample as well.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Baker L, McNulty JK. Shyness and marriage: Does shyness shape even established relationships? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:665–676. doi: 10.1177/0146167210367489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker L, McNulty JK. Self-compassion and relationship maintenance: The moderating roles of conscientiousness and gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0021884. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Worthington EL, Jr, Parrott L, III, O’Connor L, Wade NG. Dispositional forgiveness: development and construct validity of the Transgression Narrative Test of Forgiveness (TNTF) Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1277–1290. [Google Scholar]

- Boster FJ, Fediuk TA, Kotowski MJ. The effectiveness of an altruistic appeal in the presence and absence of favors. Communication Monographs. 2001;68:340–346. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Fincham FD. A contextual model for advancing the study of marital interaction. In: Fletcher GJO, Fincham FD, editors. Cognition in close relationships. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York, NY: Guilford; 1998. pp. 394–428. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RP. Measuring individual differences in the tendency to forgive: Construct validity and links with depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:759–771. doi: 10.1177/0146167203029006008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Application of hierarchical linear models to assessing change. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW, Congdon RT. HLM: Hierarchical linear modeling with the HLM/2L and HLM/3L programs. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Burger JM, Horita M, Kinoshita L, Roberts K, Vera C. The effects of time on the norm of reciprocity. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1997;19:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Schaufeli WB. Reciprocity in interpersonal relationships: An evolutionary perspective on its importance for health and well-being. European Review of Social Psychology. 1999;10:259–291. [Google Scholar]

- Cloke K. Revenge, forgiveness, and the magic of mediation. Mediation Quarterly. 1993;11:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle-Shapiro JAM, Kessler I. Reciprocity through the lens of the psychological contract: Employee and employer perspectives. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. 2002;11:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport DS. The functions of anger and forgiveness: Guidelines for psychotherapy with victims. Psychotherapy. 1991;28:140–133. [Google Scholar]

- Denton RT, Martin MW. Defining forgiveness: An empirical exploration of process and role. American Journal of Family Therapy. 1998;26:281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Edlund JE, Sagarin BJ, Johnson BS. Reciprocity and the belief in a just world. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:589–596. [Google Scholar]

- Enright RD. Human Development Study Group. The moral development of forgiveness. In: Kurtines W, Gewirtz J, editors. Handbook of moral behavior and development. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 123–152. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SR. Forgiving in close relationships. Advances in Psychology Research. 2001;7:163–197. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH. Forgiveness in marriage: Implications for psychological aggression and constructive communication. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher TD, McNulty JK. Neuroticism and marital satisfaction: The mediating role played by the sexual relationship. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:112–122. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbons RP. The cognitive and emotive uses of forgiveness in the treatment of anger. Psychotherapy. 1986;23:629–633. [Google Scholar]

- Frye NE, McNulty JK, Karney BR. How do constraints on leaving a marriage affect behavior within the marriage? Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:153–161. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. A broad-bandwidth, public-domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In: Mervielde I, Deary IJ, De Fruyt F, Ostendorf F, editors. Personality psychology in Europe. Vol. 7. Tilburg, Netherlands: Tilburg University Press; 1999. pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon K, Baucom DH, Snyder DK. Forgiveness in couples: Divorce, infidelity, and couples therapy. In: Worthington EL, editor. Handbook of forgiveness. New York, NY: Routledge; 2005. pp. 407–422. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KC, Burton S, Porter L. Predicting the intentions of women in domestic violent shelters to return to partners: Does forgiveness play a role? Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:331–338. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. Marital interaction. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. Psychology and the study of marital processes. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:169–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Markman H, Notarius C. The topology of marital conflict: A sequential analysis of verbal and nonverbal behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1977;53:461–477. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner AW. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review. 1960;25:161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE. Observation of couple conflicts: Clinical assessment applications, stubborn truths, and shaky foundations. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:5–35. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns JN, Fincham FD. A prototype analysis of forgiveness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:838–855. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keohane RO. Reciprocity in international relations. International Organization. 1986;40:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lawler KA, Younger JW, Piferi RL, Billington E, Jobe R, Edmondson K, Jones WH. A change of heart: Cardiovascular correlates of forgiveness in response to interpersonal conflicts. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:373–393. doi: 10.1023/a:1025771716686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler KA, Younger JW, Piferi RL, Jobe RL, Edmonsdson KA, Jones WH. The unique effects of forgiveness on health: An exploration of pathways. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;28:157–167. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-3665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WF, Mack D, Enright RD, Krahn D, Baskin TW. Effects of forgiveness therapy on anger, mood, and vulnerability to substance use among inpatient substance-dependent clients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1114–1121. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little KC, McNulty JK, Russell VM. Sex buffers intimates against the negative implications of attachment insecurity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:484–498. doi: 10.1177/0146167209352494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchies LB, Finkel EJ, McNulty JK, Kumashiro M. The doormat effect: When forgiving erodes self-respect and self-concept clarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98:734–749. doi: 10.1037/a0017838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl BW, Taylor MJ, Stevenson R, Roberts KD. Process-based forgiveness interventions: A meta-analytic review. Research on Social Work Practice. 2008;18:465–478. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Rachal KC, Sandage SJ, Worthington EL, Jr, Brown SW, Hight TL. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1586–1603. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.6.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Worthington EL, Rachal KC. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:321–336. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK. Forgiveness in marriage: Putting the benefits into context. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008a;22:171–175. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK. Neuroticism and interpersonal negativity: The independent contributions of behavior and perceptions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008b;34:1439–1450. doi: 10.1177/0146167208322558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK. Forgiveness increases the likelihood of subsequent partner transgressions in marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010a;24:787–790. doi: 10.1037/a0021678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK. When positive processes hurt relationships. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010b;19:167–171. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Fisher TD. Gender differences in response to sexual expectancies and changes in sexual frequency: A short-term longitudinal investigation of sexual satisfaction in newly married heterosexual couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:229–240. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Hellmuth JC. Emotion regulation and intimate partner violence in newlyweds. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:794–797. doi: 10.1037/a0013516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Karney BR. Positive expectations in the early years of marriage: Should couples expect the best or brace for the worst? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:729–743. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, O’Mara EM, Karney BR. Benevolent cognitions as a strategy of relationship maintenance: Don’t sweat the small stuff. but it’s not all small stuff. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:631–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Russell VM. When “negative” behaviors are positive: A contextual analysis of the long-term effects of problem-solving behaviors on changes in relationship satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98:587–604. doi: 10.1037/a0017479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North J. Wrongdoing and forgiveness. Philosophy. 1987;62:499–508. [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1983;45:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Overall NC, Fletcher GJO, Simpson JA, Sibley CG. Regulating partners in intimate relationships: The costs and benefits of different communication strategies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:620–639. doi: 10.1037/a0012961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan DT. Effects of a favor and liking on compliance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1971;7:627–639. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE. Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1980;16:172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE. A longitudinal test of the investment model. The development (and deterioration) of satisfaction and commitment in heterosexual involvements. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45:100–117. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Verette J, Whitney GA, Slovik LE, Lipkus I. Accommodation processes in close relationships: Theory and preliminary empirical evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Russell VM, McNulty JK. Frequent sex protects intimates from the negative implications of their neuroticism. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2011;2:220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Sells JN, Hargrave TD. Forgiveness: A review of the theoretical and empirical literature. Journal of Family Therapy. 1998;20:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Contingencies of reinforcement. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut JW, Kelley HH. The social psychology of groups. Oxford, England: Wiley; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang J, McCullough ME, Fincham F. The longitudinal association between forgiveness and relationship closeness and commitment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:448–472. [Google Scholar]

- Van Yperen NW, Buunk BP. Social comparison and social exchange in marital relationships. In: Lerner MJ, Mikula G, editors. Entitlement and the affectional bond: Justice in close relationships. New York, NY: Plenum; 1994. pp. 89–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace HM, Exline JJ, Baumeister RF. Interpersonal consequences of forgiveness: Does forgiveness deter or encourage repeat offenses? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:453–460. [Google Scholar]

- Walster E, Walster GW, Berscheid E. Equity: Theory and research. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Weiss RL, Patterson GR. A behavioral analysis of the determinants of marital satisfaction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:802–811. doi: 10.1037/h0037524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]