Abstract

The field of positive psychology rests on the assumption that certain psychological traits and processes are inherently beneficial for well-being. We review evidence that challenges this assumption. First, we review data from 4 independent longitudinal studies of marriage revealing that 4 ostensibly positive processes—forgiveness, optimistic expectations, positive thoughts, and kindness—can either benefit or harm well-being depending on the context in which they operate. Although all 4 processes predicted better relationship well-being among spouses in healthy marriages, they predicted worse relationship well-being in more troubled marriages. Then, we review evidence from other research that reveals that whether ostensibly positive psychological traits and processes benefit or harm well-being depends on the context of various noninterpersonal domains as well. Finally, we conclude by arguing that any movement to promote well-being may be most successful to the extent that it (a) examines the conditions under which the same traits and processes may promote versus threaten well-being, (b) examines both healthy and unhealthy people, (c) examines well-being over substantial periods of time, and (d) avoids labeling psychological traits and processes as positive or negative.

Keywords: positive psychology, marriage, context, well-being, health

Over the past two decades, there has been a strong push to study various psychological traits and processes presumed to be positive—that is, beneficial for well-being. This push gained considerable impetus during the 1998 Presidential Address of the American Psychological Association, when then President Martin E. P. Seligman (1999) formally established the field of positive psychology. During that address and in an article published in the American Psychologist (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000b), Seligman argued that psychology before that point had been too focused on what is wrong with people and thus could not tell us what is right with people—an understanding he argued was necessary if we are to help people achieve their full potential. Accordingly, Seligman introduced the field of positive psychology as a way to promote the study of psychological characteristics presumed to benefit well-being. The field has grown spectacularly since then, with the appearance of special journal issues (e.g., American Psychologist, Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000a; Psychological Inquiry, 2003, Vol. 14, No. 2; Review of General Psychology, Baumeister & Simonton, 2005), handbooks (e.g., Linley & Joseph, 2004; Ong & van Dulmen, 2007; Snyder & Lopez, 2002), textbooks (e.g., Carr, 2004; Compton, 2005; Peterson, 2006), and a new journal in 2006, the Journal of Positive Psychology.

Notwithstanding this spectacular growth, some have observed that positive psychologists have not paid enough attention to the interpersonal context in which people spend much of their lives (Fincham & Beach, 2010; Maniaci & Reis, 2010). The purpose of the current article is to show that doing so provides a crucial organizing principle thus far missing from the study of optimal functioning: Psychological traits and processes are not inherently positive or negative; instead, whether psychological characteristics promote or undermine well-being depends on the context in which they operate. If true, this principle indicates a need to think beyond positive psychology.

Challenging a Key Assumption

When Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000b) introduced positive psychology in their seminal article, they stated,

The field of positive psychology at the subjective level is about valued subjective experiences: well-being, contentment, and satisfaction (in the past); hope and optimism (for the future); and flow and happiness (in the present). At the individual level, it is about positive individual traits: the capacity for love and vocation, courage, interpersonal skill, aesthetic sensibility, perseverance, forgiveness, originality, future mindedness, spirituality, high talent, and wisdom. At the group level, it is about the civic virtues and the institutions that move individuals toward better citizenship: responsibility, nurturance, altruism, civility, moderation, tolerance, and work ethic. (p. 5)

By defining the field of positive psychology as numerous psychological characteristics, Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi implied that the listed characteristics are inherently positive. But are they?

Attending to the interpersonal context in which these and other so-called positive psychological characteristics operate suggests otherwise. Consider a woman in a physically abusive relationship, for example. Most existing research, much of which is based primarily on people not facing physical abuse, suggests that people and their relationships benefit to the extent that they (a) attribute their partners’ negative behavior to external sources rather than dispositional characteristics of those partners (see Bradbury & Fincham, 1990), (b) are optimistic about future interactions with their partners (McNulty & Karney, 2002), (c) forgive their partners (Fincham, Hall, & Beach, 2006), (d) remember their positive experiences with their relationships and forget their more negative ones (Karney & Coombs, 2000), and (e) remain committed to their partners (Rusbult, 1980). In reality, however, those strategies may harm a woman in a physically abusive relationship. Rather than thinking and behaving so charitably, such women may benefit from (a) attributing their partner’s abuse to his dispositional qualities rather than external sources, (b) expecting the abuse to continue, (c) not forgiving the abuse, (d) remembering the abuse, and (e) being less committed to the relationship. In other words, so-called positive processes can sometimes be harmful for well-being, whereas processes thought to be negative can sometimes be beneficial for well-being.

Of course, most people do not face severe interpersonal abuse, leaving it possible that these and other so-called positive psychological processes are beneficial for most people. We challenge this assumption is the next section, however, by describing data from four longitudinal studies of newlywed couples drawn from the community to show that whether several psychological characteristics claimed as positive by the positive psychology movement help or harm relationship well-being depends on the context in which they operate.

A Contextual View of the Implications of Psychological Processes for Well-Being

Lewin (1935) recognized that behavior is not determined solely by people’s psychological characteristics but is instead determined jointly by the interplay between those characteristics and qualities of people’s social environments. Our perspective is very similar; we argue that well-being is not determined solely by people’s psychological characteristics but instead is instead determined jointly by the interplay between those characteristics and qualities of people’s social environments. Data from four independent longitudinal studies of marriage provide direct evidence for this perspective.

Forgiveness

Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000b) identified forgiveness as a key positive individual trait. Indeed, several studies indicate that more forgiving individuals show signs of better physical and psychological health (e.g., Berry, Worthington, O’Connor, Parrott, & Wade, 2005; Brown, 2003; Lawler et al., 2003, 2005; Toussaint, Williams, Musick, & Everson, 2001; Witvliet, Ludwig, & Vander Laan, 2001). Witvliet et al. (2001), for example, showed that compared with lack of forgiveness, forgiveness had beneficial effects on systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and mean arterial pressure. Likewise, using a national probability sample of U.S. adults, Toussaint et al. (2001) found that forgiveness was negatively related to psychological distress and positively related to life satisfaction. Other work indicates forgiveness is also associated with better relationship health (e.g., Fincham, Beach, & Davila, 2007; McCullough et al., 1998; Paleari, Regalia, & Fincham, 2005). Fincham et al. (2007), for instance, showed that wives’ forgiveness was positively associated with improvements in husbands’ self-reported communication 12 months later.

Nevertheless, a few studies suggest that forgiveness may not always be so beneficial (Gordon, Burton, & Porter, 2004; McNulty, 2010, 2011). Gordon et al. (2004), for example, sampled women at a domestic violence shelter and reported that more forgiving women reported being more likely to return to their abusive partners. Moreover, McNulty (2010) recently found that whereas less forgiving spouses experienced declines in the frequency with which their partners perpetrated psychological and physical aggression over the first five years of marriage, more forgiving spouses actually experienced stable or growing levels of psychological and physical aggression over those years.

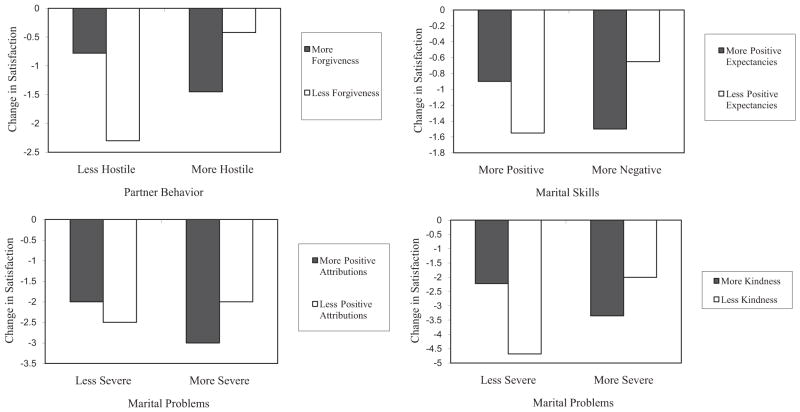

So, is forgiveness positive psychology or negative psychology? We argue it is neither. Rather, forgiveness is a process that can be either beneficial or harmful, depending on characteristics of the relationship in which it occurs. McNulty (2008) used a sample of 72 newlywed couples who reported their marital satisfaction up to four times over the course of two years to make this point. Although forgiveness was positively associated with marital satisfaction initially, the association between spouses’ forgiveness and changes in their marital satisfaction depended on the frequency with which their partners directed hostile behaviors (e.g., sarcasm, insulting, swearing) toward them. As can be seen in the top left panel of Figure 1, even though forgiveness helped maintain marital satisfaction among spouses married to partners who rarely engaged in hostile behaviors, forgiveness was associated with steeper declines in satisfaction among spouses married to partners who more frequently engaged in hostile behaviors.

Figure 1. Psychological Processes in Context.

Note. Each plot depicts the predicted means for people one standard deviation above and below the mean on each variable involved in the interaction. Data depicted in the upper left plot were drawn from a broader study of 72 newlywed couples from Northern Ohio assessed from 2003 through 2006. Data depicted in the upper right plot were drawn from a broader study of 82 newlywed couples from Northern Florida assessed from 1998 through 2002. Data depicted in the bottom left plot were drawn from the same study of 82 couples depicted in the upper right and a broader study of 169 newlywed couples from Northern Florida assessed from 2001 through 2005. Data depicted in the bottom right plot were drawn from a broader study of 135 newlywed couples from Eastern Tennessee assessed from 2006 through 2008.

Luchies, Finkel, McNulty, and Kumashiro (2010) demonstrated similar implications of forgiveness for people’s views of themselves. In one study (Study 1), whereas more forgiving spouses experienced increases in self-respect over time when they were married to partners who were high in agreeableness, more forgiving spouses experienced decreases in self-respect over time when they were married to partners who were low in agreeableness. Further, an experimental replication (Study 3) provided causal evidence for the contextualized implications of forgiveness. People randomly assigned to believe they had forgiven a transgressor who had made amends experienced an increased sense of self-concept clarity, whereas people randomly assigned to believe they had forgiven a transgressor who had not made amends experienced a decreased sense of self-concept clarity.

The implications of forgiveness for subsequent partner offending appear to depend on characteristics of that partner as well. McNulty and Russell (2011) demonstrated that spouses’ tendencies to forgive their partners interacted with those partners’ levels of agreeableness to predict changes in the extent to which those partners continued their psychological aggression over the first two years of marriage. Specifically, the tendency to forgive agreeable partners was associated with decreases in those partners’ use of psychological aggression over time, whereas the tendency to forgive disagreeable partners was associated with increases in those partners’ use of psychological aggression over time.

Of course, the study of forgiveness is a relative newcomer to the field of psychological research and widespread agreement on the very nature of this construct has not been achieved (Fincham, 2009). For example, researchers disagree on whether forgiveness is simply the absence of negative feelings (e.g., McCullough, Fincham, & Tsang, 2003) or also the presence of positive feelings (e.g., Fincham, Beach, & Davila, 2004). Further, whereas most psychologists agree that forgiveness does not imply condoning or reconciliation, some estimates indicate that as many as 20% of laypersons believe forgiveness implies condoning and/or reconciliation (Kearns & Fincham, 2004). Notably, all of the research on the contextual implications of forgiveness has left definitions of forgiveness up to participants themselves. As a result, one might reasonably wonder whether these studies of forgiveness are representative of the traits central to positive psychology. We therefore turn to consider other characteristics identified as positive in the positive psychology movement.

Optimism

One of the core constructs of the positive psychology movement is optimism (Carver & Scheier, 2002; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000b), defined as generalized expectancies for desirable future outcomes (Carver, Scheier, Segerstrom, 2010). Indeed, optimism and expectancies for desirable outcomes have been positively associated with individual well-being in numerous studies (e.g., Aspinwall & Richter, 1999; Brissette, Scheier, & Carver, 2002; Scheier & Carver, 1985; Taylor, Lichtman, & Wood, 1984; for a review, see Carver, Scheier, & Segerstrom, 2010). Brissette et al. (2002), for example, reported that optimism was associated with decreased stress and depression among participants experiencing the transition to college. Additionally, optimism and expectancies for favorable outcomes have been positively associated with interpersonal well-being in numerous studies (Downey, Freitas, Michaelis, & Khouri, 1998; McNulty & Karney, 2002; Srivastava, McGonigal, Richards, Butler, & Gross, 2006). Srivastava et al. (2006), for example, reported that more optimistic intimates perceived more support from their partners than did less optimistic intimates.

However, other studies indicate that optimism and expectancies for desirable outcomes can have harmful consequences (Gibson & Sanbonmatsu, 2004; Isaacowitz & Seligman, 2002; Norem, 2001; Shepperd & McNulty, 2002). Gibson and Sanbonmatsu (2004), for example, reported three studies showing that optimists are less likely to disengage from gambling— even after experiencing gambling losses. Further, in contrast to the typically positive implications of optimism among young and middle-aged participants, Isaacowitz and Seligman (2002) found that optimism was associated with increased depression over time in a sample of older participants.

As with forgiveness, these contrasting findings can be reconciled by recognizing that whether optimism and expectancies for desirable outcomes have beneficial or harmful implications depends on the context in which they occur. McNulty and Karney (2004) used a sample of 82 newlywed couples who reported their marital satisfaction eight times over the course of four years to make this point. Although expectancies for desirable relationship outcomes (e.g., improved marital satisfaction) were associated with higher levels of satisfaction initially, the effects of those expectancies on changes in marital satisfaction depended on spouses’ abilities to confirm them. As can be seen in the top right panel of Figure 1, although expectancies for desirable outcomes helped maintain satisfaction among spouses who tended to think and behave like satisfied couples—that is, make positive attributions for one another’s undesirable behaviors (see Bradbury & Fincham, 1990) and refrain from criticizing one another (see Heyman, 2001)—those same expectancies led to declines in satisfaction among spouses who lacked those skills.

Benevolent Attributions

Just as positive psychologists have labeled optimistic expectancies for the future as positive, they have labeled optimistic or benevolent explanations of the present as positive (e.g., Peterson & Steen, 2002; Seligman, 1991; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000b). Seeming to support this view, the tendency to make relatively optimistic interpretations of undesirable experiences has been associated with both individual (e.g., Alloy & Abramson, 1979; Anderson, 1999; Golin, Sweeney, & Shaeffer, 1981; Kuiper, 1978; Needles & Abramson, 1990) and interpersonal well-being (e.g., for reviews, see Bradbury & Fincham, 1990; Fincham, 2001). Regarding individual well-being, Golin et al. (1981) demonstrated that college students who tended to view the causes of undesirable outcomes as less global and less stable experienced fewer depressive symptoms two months later. At the interpersonal level, Karney and Bradbury (2000) demonstrated that married spouses who made more external, less global, and less stable attributions for their partners’ negative behaviors remained more satisfied with their relationships over four years. In fact, this pattern of attributions was at one time labeled relationship enhancing in the marital literature (Holtzworth-Munroe & Jacobson, 1985) and gave rise to therapy attempts to inculcate such attributions (e.g., Baucom & Lester, 1986), attempts that strongly influenced the way couples therapy is practiced today (see Epstein & Baucom, 2002).

However, interpreting the causes of negative experiences in a favorable manner is not always beneficial. For example, some authors have noted that optimistic interpretations about one’s own negative behavior can undermine the motivation to seek improvements (e.g., Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998; Major & Schmader, 1998; Steele, Spencer, & Aronson, 2002). Further, several studies of relationships suggest that women who make more external attributions for their partners’ negative behavior run the risk of experiencing psychological or physical abuse (Katz, Arias, Beach, Brody, & Roman, 1995; Pape & Arias, 2000; Truman-Schram, Cann, Calhoun, & Vanwallendael, 2000).

Two independent longitudinal studies of marriage reconciled these paradoxical effects of benevolent attributions for relationships by attending to the context of the relationship. McNulty, O’Mara, and Karney (2008) used one longitudinal study of 82 newlywed couples and a second longitudinal study of 169 newlywed couples to demonstrate that even though benevolent attributions of a partner’s undesirable behaviors were positively associated with marital satisfaction initially, the effects of such attributions on changes in marital satisfaction depended on the severity of the problems that partners faced in their marriages. As can be seen in the bottom left panel of Figure 1, more benevolent attributions (e.g., believing the partner was not responsible for an undesirable behavior) most effectively maintained satisfaction among spouses facing relatively minor problems. In contrast, however, less benevolent attributions (e.g., believing the partner was responsible for an undesirable behavior) most effectively maintained satisfaction among spouses who faced more severe problems. Notably, subsequent analyses revealed that these interactive effects were mediated by changes in the severity of the problems themselves. Spouses who made benevolent attributions in the context of severe problems experienced declines in satisfaction because their problems remained severe, whereas spouses who made less benevolent attributions in the context of severe problems experienced more stable satisfaction because their problems improved.

Kindness

Positive psychologists have also extolled the benefits of kindness (Duckworth, Steen, & Seligman, 2005; Kauffman, 2006; Peterson, 2006; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). Consistent with this view, numerous studies provide evidence for intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of kindness (e.g., Buchanan & Bardi, 2010; Otake, Shimai, Tanaka-Matsumi, Otsui, & Frederickson, 2006; Pasch & Bradbury, 1998; Tkach, 2006; for a review, see Post, 2005). Buchanan and Bardi (2010), for example, demonstrated that, compared with control participants, participants randomly assigned to perform acts of kindness every day for 10 days became more satisfied with their lives. Likewise, studies of intimate relationships demonstrate that being kind to a partner during a time of personal need is associated with greater relationship satisfaction (e.g., Pasch & Bradbury, 1998). Even being kind to oneself appears to promote well-being (Leary, Tate, Adams, Allen, & Hancock, 2007; Neff, 2003). In this regard, Leary et al. (2007) reported that people who reported a tendency to be self-compassionate, or treat themselves kindly after their mistakes, reported less negative affect than people who reported a tendency to be less self-compassionate.

Nevertheless, several studies suggest that kindness can have harmful implications. For instance, research on the most advantageous strategies to use while playing prisoner’s dilemma games indicates that kinder players (i.e., those who are more likely to cooperate) experience more competitions as those games develop over time (Axelrod, 1980). Likewise, other research indicates that unkindness can offer benefits to relationships (Cohan & Bradbury, 1997; Gottman & Krokoff, 1989; Heavey, Layne, & Christensen, 1993; Karney & Bradbury, 1997). For example, Karney and Bradbury (1997) used growth curve modeling to demonstrate that wives’ tendencies to engage in unkind behaviors during problem-solving discussions (e.g., rejection, criticism) predicted more stable satisfaction among both husbands and wives across eight assessments of marital satisfaction spanning four years.

Once again, longitudinal research demonstrates that whether unkindness harms or benefits relationships depends on the nature of those relationships. Using one sample of 72 newlywed couples who reported their marital satisfaction up to eight times over the course of five years and a second sample of 135 newlywed couples who reported their marital satisfaction up to three times over the course of one year, McNulty and Russell (2010) demonstrated that, even though being unkind during problem-solving interactions was negatively associated with marital satisfaction initially, the association between spouses’ unkind behaviors (e.g., criticizing the partner, rejecting the partner) and changes in their marital satisfaction depended on the severity of the problems those spouses faced in their marriages. As can be seen in the bottom right panel of Figure 1, even though observations of spouses’ tendencies to blame, command, and reject their partners predicted greater declines in marital satisfaction among those who faced rather minor problems, those same behaviors predicted more stable satisfaction among those who faced more severe marital problems. As in McNulty et al.’s (2008) study described earlier, this association emerged because the more negative behaviors exchanged in the marriages characterized by more severe problems were associated with improvements in those problems.

Although McNulty and Russell’s (2010) research examined the effects of unkindness, other research suggests that the effects of kindness are just as contextual. Specifically, Maisel and Gable (2009) recently reported that the implications of one partner’s support for the other partner’s relationship satisfaction depended on how responsive that support was to the recipient. Whereas visible support was positively associated with relationship well-being when it was seen as responsive to one’s needs, it was negatively associated with relationship well-being when it was seen as unresponsive to those needs.

The Moderating Role of Noninterpersonal Contexts

Although our perspective was informed by the role of the interpersonal context in determining whether processes have beneficial or harmful implications, it is important to note that noninterpersonal contexts appear to play a similar role (Baker & McNulty, 2011; Cohen et al., 1999; Fredrickson & Losada, 2005; Noordewier & Stapel, 2010; Sieber et al., 1992). Cohen et al. (1999), for example, demonstrated that whether dispositional optimism was associated with better or worse immune responding depended on whether participants faced chronic or acute stressors. Whereas optimism was associated with better immune responding among people facing more acute stressors, it was associated with worse immune responding among people facing more chronic stressors. Likewise, Baker and McNulty (2011) recently found that the relationship implications of men’s tendencies to be kind to themselves following interpersonal mistakes are moderated by conscientiousness. Whereas self-compassionate men who were high in conscientiousness (a) reported being more motivated to correct their interpersonal mistakes, (b) were observed as more likely to engage in constructive problem-solving behaviors, and (c) experienced stable relationship satisfaction over time, self-compassionate men who were low in conscientiousness (a) reported being less motivated to correct their interpersonal mistakes, (b) were observed as less likely to engage in constructive problem-solving behaviors, and (c) experienced steeper declines in relationship satisfaction over time. Finally, Fredrickson and Losada (2005) reported that the implications of desirable emotions for well-being depend on their frequency relative to undesirable emotions. Whereas having fewer than 3-to-1 desirable-to-undesirable emotions is harmful for well-being, it is also harmful to have more than about 11-to-1 desirable-to-undesirable emotions.

Finally, although our review has focused mostly on the role of context in determining how psychological characteristics shape individual well-being, it is important to note that the way psychological characteristics shape group well-being also appears to depend on the context in which they operate. In contrast to Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi’s (2000b) claim that altruism is a key process that promotes collective well-being, for example, Batson, Batson, et al. (1995) demonstrated that altruistic motivations can actually undermine collective well-being in some circumstances. Participants randomly assigned to feel empathy for one member of a group, an emotion Batson (1998) argued promotes altruism, allocated more resources to that member of the group to the detriment of the group as a whole. Further, Batson, Klein, Highberger, and Shaw (1995) demonstrated that altruistic motivations can lead people to violate their own moral principles to the detriment of others. Compared with control participants, participants randomly assigned to feel empathy for a terminally ill child ostensibly on a waiting list to receive medication that would substantially improve her quality of life were more likely to allow her to skip ahead of other children on the waiting list to immediately receive the drug, even though they believed doing so was wrong.

Summary

In summary, a key assumption of the positive psychology movement is that certain psychological traits and processes constitute a positive psychology that should be promoted to realize optimal functioning. In contrast to this assumption, our review indicates that psychological traits and processes are not inherently positive or negative; rather, their implications for well-being depend on the circumstances in which they operate. Accordingly, the future course of positive psychology needs to be carefully considered. We do so in the next section.

An Alternative Approach to the Study of Well-Being

Where should psychologists go from here? To be clear, our goal is not to undercut the important contribution positive psychology has already made to our discipline. Thanks to the positive psychology movement, researchers are now studying psychological traits and processes that have received little attention in the past. Further, it is not our goal to argue that attempting to understand how people achieve optimal well-being is unimportant. Such an understanding is extremely important. Rather, our goal is to argue that we need to take a different approach to the study of well-being.

First, psychologists need to move beyond examining the main effects of traits and processes that may promote well-being on average to study the factors that determine when, for whom, and to what extent those factors are associated with well-being. Failing to do so will result in an incomplete understanding of the contextual nature of psychological characteristics that could have harmful implications. For example, numerous positive psychologists have argued that the knowledge acquired from research on positive psychology should inform therapy and prevention efforts (e.g., Bono & McCullough, 2006; Duckworth et al., 2005; Frisch, 2006; Ingram & Snyder, 2006; Karwoski, Garratt, & Ilardi, 2006; Seligman, 2002; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000b; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Although the traits and processes studied by positive psychologists may indeed benefit some clients, such benefits may be the exception rather than the rule. People who seek therapy usually do so because they are experiencing suboptimal outcomes. Our review suggests that the psychological characteristics that benefit people experiencing optimal circumstances may not only fail to help people experiencing suboptimal circumstances, but may harm them.

It is important to note that some positive psychologists have made similar arguments. Gable and Haidt (2005), for example, argued that “positive psychology must move beyond the description of main effects (optimism, humor, forgiveness, and curiosity are good) and begin to look more closely at the complex interactions that are the hallmark of most of psychology” (p. 108). Some researchers within the field of positive psychology provide a model for such research. For example, Fredrickson and Losada’s (2005) research on the optimal ratio of positive to negative emotions described earlier demonstrates that whereas desirable emotions can be beneficial in the context of a few undesirable emotions, those same emotions can be harmful in the context of too few undesirable emotions. Similarly, Maisel and Gable’s (2009) research, also described earlier, demonstrates that even though support provision can be beneficial to a relationship when it is responsive to one’s needs, it can be detrimental to a relationship when it is not responsive to one’s needs. Both programs of research provide important insights into the contextual nature of psychological processes many presume to be beneficial.

Second, to adequately capture the moderating role of various contextual factors, we need to study the implications of psychological characteristics in the context of both health and dysfunction and in the context of both happy and unhappy people. Just as studying dysfunction cannot tell researchers how to promote flourishing, as some positive psychologists have argued (e.g., Gable & Haidt, 2005; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Seligman & Pawelski, 2003), studying flourishing cannot tell us how to improve or prevent suffering. As our review makes clear, the processes that benefit people facing optimal circumstances can harm people facing suboptimal circumstances. Accordingly, understanding how to relieve suffering requires studying people who are suffering, and understanding how to prevent suffering requires studying people at risk for suffering.

Some researchers within the field of positive psychology provide a model for addressing this issue as well. Phipps (2007), for example, described the benefits of a repressive adaptive style for well-being among children diagnosed with cancer. Kashdan, Uswatte, and Julian (2006) demonstrated the positive association between gratitude and well-being among war veterans diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder. Without such work, the potential breadth of the benefits of these processes would be less clear.

Third, researchers need to move beyond cross-sectional studies to examine the implications of psychological traits and processes over substantial periods of time. In all four longitudinal studies described earlier, processes presumed to be beneficial by positive psychologists were indeed associated with better well-being initially. Nevertheless, those same processes were harmful to some people over substantial periods of time—years in those cases. Accordingly, developing a complete understanding of how to promote well-being requires research that provides insights into not only the short-term implications of various psychological traits and processes but also the long-term implications of those characteristics.

Although some positive psychologists have indeed used longitudinal methods to evaluate the effectiveness of various positive psychological interventions for promoting well-being, the majority of those studies have examined only the short-term implications of such interventions using immediate postintervention follow-ups (for a review, see Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Accordingly, it remains unclear whether the immediate benefits observed in those studies last over substantial periods of time or whether the presumed positive psychological characteristics become harmful for some people—as they did in the longitudinal studies of marriage described earlier.

Ideally, research will follow all three of these recommendations. Studying psychologically healthy and unhealthy people without examining whether the different contexts of those people moderate the implications of various psychological traits and processes will provide information about what is beneficial for the average person in the sample—not everyone in the sample. Likewise, examining potential contextual moderators of the implications of psychological traits and processes for well-being in samples of people experiencing mostly positive or mostly negative conditions will provide a restricted view of the contextual implications of those psychological characteristics—not a view based on a full range of measurement. In addition, examining the contextual implications of psychological processes for well-being in diverse samples but doing so only cross-sectionally or over short periods of time may provide insights into only the short-term implications of such characteristics—not the long-term consequences that may be more harmful for some people. Only by examining the short- and long-term contextual implications of psychological processes for well-being in diverse samples can psychologists develop a complete understanding of well-being.

Beyond Positive Psychology?

Whereas the first three recommendations offer ways to improve the field of positive psychology, some of which have already been suggested and/or followed by some positive psychologists, this last recommendation questions its existence. Specifically, as earlier critics of positive psychology have contended (e.g., Lazarus, 2003), psychologists need to move beyond labeling psychological traits and processes as positive. Continuing to do so imposes values on science that influence not only what we study but also what we predict and thus report. Although most philosophers of science agree that values are an inextricable part of the scientific process (see Kincaid, Dupré, & Wylie, 2007), using values to form hypotheses allows them undue influence. Indeed, given that unpredicted effects are far less likely to be published than predicted results (Mahoney, 1977), presuming and thus predicting that a particular psychological characteristic will benefit people could lead researchers to accumulate knowledge consistent with that presumption— even if it is inaccurate.

Some positive psychologists have noted that they look forward to the time when positive psychology is “just plain psychology” (Gable & Haidt, 2005, p. 109) because it will have realized its attempt to provide “an understanding of the complete human condition” (p. 109). From our different perspective, we argue that positive psychology needs to be thought of as just plain psychology before psychologists can have a fuller understanding of the complete human condition. That is, an understanding of the complete human condition requires recognizing that psychological traits and processes are not inherently positive or negative—whether they have positive or negative implications depends on the context in which they operate. Psychology is not positive or negative—psychology is psychology.

Contributor Information

James K. McNulty, University of Tennessee

Frank D. Fincham, Florida State University

References

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: Sadder but wiser? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1979;108:441–485. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.108.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA. Attributional style, depression, and loneliness: A cross-cultural comparison of American and Chinese students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:482–499. doi: 10.1177/0146167299025004007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Richter L. Optimism and self-mastery predict more rapid disengagement from unsolvable tasks in the presence of alternatives. Motivation and Emotion. 1999;23:221–245. doi: 10.1023/A:1021367331817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod R. More effective choice in the prisoner’s dilemma. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 1980;24:379–403. doi: 10.1177/002200278002400301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LR, McNulty JK. Self-compassion and relationship maintenance: The moderating roles of conscientiousness and gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100:853–873. doi: 10.1037/a0021884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD. Altruism and prosocial behavior. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4. Vol. 2. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 282–316. [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, Batson JG, Todd RM, Brummett BH, Shaw LL, Aldeguer CMR. Empathy and the collective good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:619–631. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, Klein TR, Highberger L, Shaw LL. Immorality from empathy-induced altruism: When compassion and justice conflict. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:1042–1054. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.68.6.1042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Lester GW. The usefulness of cognitive restructuring as an adjunct to behavioral marital therapy. Behavior Therapy. 1986;17:385–403. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(86)80070-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Simonton DK, editors. Positive psychology [Special issue] Review of General Psychology. 2005;9(2) [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Worthington EL, Jr, O’Connor LE, Parrott L, III, Wade NG. Forgivingness, vengeful rumination, and affective traits. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:183–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono G, McCullough ME. Positive responses to benefit and harm: Bringing forgiveness and gratitude into cognitive psychotherapy. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;20:147–158. doi: 10.1891/jcop.20.2.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Fincham FD. Attributions in marriage: Review and critique. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:3–33. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissette I, Scheier MF, Carver CS. The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:102–111. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RP. Measuring individual differences in the tendency to forgive: Construct validity and links with depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:759–771. doi: 10.1177/0146167203029006008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan KE, Bardi A. Acts of kindness and acts of novelty affect life satisfaction. Journal of Social Psychology. 2010;150:235–237. doi: 10.1080/00224540903365554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A. Positive psychology: The science of happiness and human strengths. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Optimism. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Handbook of positive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC. Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:879–889. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohan CL, Bradbury TN. Negative life events, marital interaction, and the longitudinal course of newlywed marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:114–128. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen F, Kearney KA, Zegans LS, Kemeny ME, Neuhaus JM, Stites DP. Differential immune system changes with acute and persistent stress for optimists vs. pessimists. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 1999;13:155–174. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1998.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WC. An introduction to positive psychology. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4. Vol. 2. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 504–553. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Freitas AL, Michaelis B, Khouri H. The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: Rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:545–560. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth AL, Steen TA, Seligman MEP. Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:629–651. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein NB, Baucom DH. Enhanced cognitive–behavioral therapy for couples: A contextual approach. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD. Attributions and close relationships: From balkanization to integration. In: Fletcher GJ, Clark M, editors. Blackwell handbook of social psychology. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell; 2001. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD. Forgiveness: Integral to a science of close relationships? In: Mikulincer M, Shaver P, editors. Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature. Washington, DC: APA Books; 2009. pp. 347–365. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH. Marriage in the new millennium: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:630–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00722.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH, Davila J. Forgiveness and conflict resolution in marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:72–81. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH, Davila J. Longitudinal relations between forgiveness and conflict resolution in marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:542–545. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Hall JH, Beach SRH. Forgiveness in marriage: Current status and future directions. Family Relations. 2006;55:415–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.callf.x-i1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Losada MF. Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist. 2005;60:678–686. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MB. Quality of life therapy: Applying a life satisfaction approach to positive psychology and cognitive therapy. New York, NY: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gable S, Haidt J. What (and why) is positive psychology? Review of General Psychology. 2005;9:103–110. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson B, Sanbonmatsu DM. Optimism, pessimism and gambling: The downside of optimism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:149–160. doi: 10.1177/0146167203259929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golin S, Sweeney PD, Shaeffer DE. The causality of causal attributions in depression: A cross-lagged panel correlational analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1981;90:14–22. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.90.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KC, Burton S, Porter L. Predicting the intentions of women in domestic violence shelters to return to partners: Does forgiveness play a role? Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:331–338. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Krokoff LJ. Marital interaction and satisfaction: A longitudinal view. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:47–52. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.57.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heavey CL, Layne C, Christensen A. Gender and conflict structure in marital interaction: A replication and extension. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:16–27. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE. Observation of couple conflicts: Clinical assessment applications, stubborn truths, and shaky foundations. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:5–35. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.13.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Jacobson NS. Causal attributions of married couples: When do they search for causes? What do they conclude when they do? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48:1398–1412. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.48.6.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE, Snyder CR. Blending the good with the bad: Integrating positive psychology and cognitive psychotherapy. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;20:117–122. doi: 10.1891/jcop.20.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Seligman MEP. Cognitive style predictors of affect change in older adults. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2002;54:233–253. doi: 10.2190/J6E5-NP5K-2UC4-2F8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Neuroticism, marital interaction, and the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:1075–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.5.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Attributions in marriage: State or trait? A growth curve analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:295–309. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Coombs RH. Memory bias in long-term close relationships: Consistency or improvement? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:959–970. doi: 10.1177/01461672002610006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karwoski L, Garratt GM, Ilardi SS. On the integration of cognitive–behavioral therapy for depression and positive psychology. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;20:159–170. doi: 10.1891/jcop.20.2.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Uswatte G, Julian T. Gratitude and hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in Vietnam War veterans. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:177–199. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Arias I, Beach SRH, Brody G, Roman P. Excuses, excuses: Accounting for the effects of partner violence on marital satisfaction and stability. Violence and Victims. 1995;10:315–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman C. Positive psychology: The science at the heart of coaching. In: Stober DR, Grant AM, editors. Evidence based coaching handbook: Putting best practices to work for your clients. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. pp. 219–253. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns JN, Fincham FD. A prototype analysis of forgiveness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:838–855. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid H, Dupré J, Wylie A. Value-free science? Ideals and illusions. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper NA. Depression and causal attributions for success and failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1978;36:236–246. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.36.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler KA, Younger JW, Piferi RL, Billington E, Jobe RL, Edmondson KA, Jones WH. A change of heart: Cardiovascular correlates of forgiveness in response to interpersonal conflicts. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:373–393. doi: 10.1023/A:1025771716686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler KA, Younger JW, Piferi RL, Jobe RL, Edmondson KA, Jones WH. The unique effects of forgiveness on health: An exploration of pathways. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;28:157–167. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-3665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Does the positive psychology movement have legs? Psychological Inquiry. 2003;14:93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Tate EB, Adams CE, Allen AB, Hancock J. Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:887–904. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin K. In: A dynamic theory of personality: Selected papers. Adams DE, Zener KE, translators. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Linley PA, Joseph S, editors. Positive psychology in practice. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Luchies LB, Finkel EJ, McNulty JK, Kumashiro M. The doormat effect: When forgiving erodes self-respect and self-concept clarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98:734–749. doi: 10.1037/a0017838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney MJ. Publication prejudices. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1977;1:161–175. doi: 10.1007/BF01173636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maisel NC, Gable SL. The paradox of received social support: The importance of responsiveness. Psychological Science. 2009;20:928–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Schmader T. Coping with stigma through psychological disengagement. In: Swim JK, Stangor C, editors. Prejudice: The target’s perspective. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 219–241. [Google Scholar]

- Maniaci MR, Reis HT. The marriage of positive psychology and relationship science: A reply to Fincham and Beach. Journal of Family Theory and Review. 2010;2:47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00037.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Fincham FD, Tsang J. Forgiveness, forbearance, and time: The temporal unfolding of transgression-related interpersonal motivations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:540–557. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Rachal KC, Sandage SJ, Worthington EL, Jr, Brown SW, Hight TL. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1586–1603. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK. Forgiveness in marriage: Putting the benefits into context. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:171–175. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK. Forgiveness increases the likelihood of subsequent partner transgressions in marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:787–790. doi: 10.1037/a0021678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK. The dark side of forgiveness: The tendency to forgive predicts continued psychological and physical aggression in marriage. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2011;37:770–783. doi: 10.1177/0146167211407077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Karney BR. Expectancy confirmation in appraisals of marital interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:764–775. doi: 10.1177/0146167202289006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Karney BR. Positive expectations in the early years of marriage: Should couples expect the best or brace for the worst? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:729–743. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, O’Mara EM, Karney BR. Benevolent cognitions as a strategy of relationship maintenance: “Don’t sweat the small stuff” but it’s not all small stuff. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:631–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Russell VM. When “negative” behaviors are positive: A contextual analysis of the long-term effects of problem-solving behaviors on changes in relationship satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98:587–604. doi: 10.1037/a0017479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Russell VM. Whether forgiveness leads to more or less reoffending depends on offender agreeableness. 2011. Forgive and forget, or forgive and regret? Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needles DJ, Abramson LY. Positive life events, attributional style, and hopefulness: Testing a model of recovery from depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:156–165. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.99.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2003;2:223–250. doi: 10.1080/15298860309027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noordewier MK, Stapel DA. Affects of the unexpected: When inconsistency feels good (or bad) Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:642–654. doi: 10.1177/0146167209357746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norem JK. The positive power of negative thinking. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, van Dulmen MHM, editors. Oxford handbook of methods in positive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Otake K, Shimai S, Tanaka-Matsumi J, Otsui K, Fredrickson BL. Happy people become happier through kindness: A counting kindnesses intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2006;7:361–375. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-3650-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paleari G, Regalia C, Fincham FD. Marital quality, forgiveness, empathy, and rumination: A longitudinal analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:368–378. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape K, Arias I. The role of perceptions and attributions in battered women’s intentions to permanently end their violent relationships. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:201–214. doi: 10.1023/A:1005498109271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pasch LA, Bradbury TN. Social support, conflict, and the development of marital dysfunction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:219–230. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C. A primer in positive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Steen T. Optimistic explanatory style. In: Snyder CR, Lopez S, editors. Handbook of positive psychology. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 244–256. [Google Scholar]

- Phipps S. Adaptive style in children with cancer: Implications for a positive psychology approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:1055–1066. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post SG. Altruism, happiness, and health: It’s good to be good. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;12:66–77. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1202_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE. Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1980;16:172–186. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(80)90007-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP. Learned optimism. New York, NY: Knopf; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP. The president’s address [printed in the 1998 APA annual report] American Psychologist. 1999;54:559–562. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP. Positive psychology, positive prevention, and positive therapy. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. Handbook of positive psychology. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology [Special issue] American Psychologist. 2000a;55(1) doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist. 2000b;55:5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Pawelski JO. Positive psychology: FAQs. Psychological Inquiry. 2003;14:159–163. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist. 2005;60:410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepperd JA, McNulty JK. The affective consequences of expected and unexpected outcomes. Psychological Science. 2002;13:85–88. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber WJ, Rodin J, Larson L, Ortega S, Cummings N, Levy S, Herberman R. Modulation of human natural killer cell activity by exposure to uncontrollable stress. Brain Behavior and Immunity. 1992;6:141–156. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(92)90014-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:467–487. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Lopez SJ. Handbook of positive psychology. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, McGonigal KM, Richards JM, Butler EA, Gross JJ. Optimism in close relationships: How seeing things in a positive light makes them so. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:143–153. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Spencer SJ, Aronson J. Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 379–440. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Lichtman RR, Wood JV. Attributions, beliefs about control, and adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:489–502. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkach CT. Unlocking the treasury of human kindness: Enduring improvements in mood, happiness and self-evaluations. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: Sciences and Engineering. 2006;67(1):603. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint LL, Williams DR, Musick MA, Everson SA. Forgiveness and health: Age differences in a U.S. probability sample. Journal of Adult Development. 2001;8:249–257. doi: 10.1023/A:1011394629736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Truman-Schram DM, Cann A, Calhoun L, Vanwallendael L. Leaving an abusive dating relationship: An investment model comparison of women who stay versus women who leave. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2000;19:161–183. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2000.19.2.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witvliet CV, Ludwig T, Vander Laan K. Granting forgiveness or harboring grudges: Implications for emotion, physiology, and health. Psychological Science. 2001;12:117–123. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]