Abstract

Contextual models of relationships and recent theories of attachment system activation suggest that experiences that promote intimacy, such as sexual intercourse, may moderate the negative implications of attachment insecurity. In two independent studies, 207 couples reported their attachment insecurity, the frequency of their sexual intercourse over the past 30 days, their expectancies for their partner’s availability, and their marital satisfaction, and in a 7-day diary they reported their daily sexual and relationship satisfaction and their expectancies for how satisfied they would be with their partners’ availability the next day. Attachment avoidance was unrelated to marital satisfaction among spouses reporting more frequent sex, and attachment anxiety was unrelated to marital satisfaction among spouses reporting more daily sexual satisfaction. Both effects were mediated by expectancies for partner availability. These findings suggest that the effects of attachment insecurity are not immutable but vary according to the context of the relationship.

Keywords: attachment, sex, marriage, relationship satisfaction, intimacy

There appears to be little hope of happiness for insecurely attached individuals, at least in terms of their romantic relationships. Study after study documents the negative interpersonal processes and outcomes of individuals with both anxious and avoidant attachment styles. Such insecurely attached individuals tend to explain their interpersonal experiences more negatively (e.g., Collins & Feeney, 2004), behave more negatively both when discussing relationship problems (e.g., Simpson, Rholes, & Phillips, 1996) and when seeking and providing support (e.g., Collins & Feeney, 2000), experience more negative daily emotions (Simpson, Collins, Tran, & Haydon, 2007), and are less satisfied with their romantic relationships in general (for review, see Cassidy & Shaver, 1999).

Yet despite the consistency of this research, more contextual approaches to the study of relationships suggest that even insecurely attached people can have satisfying relationships, given particular protective factors. Karney and Bradbury’s (1995) stress–vulnerability–adaptation model, for example, notes that the effects of enduring vulnerabilities, like attachment style, are moderated by other enduring traits and external factors. Nevertheless, we are aware of no research that has demonstrated any personal or relationship factors that protect both anxious and avoidant intimates from the negative implications of their insecure attachment representations.

The overarching goal of the current research was to investigate whether the frequency and/or quality of an intimacy-promoting behavior, sexual intercourse, moderates the effects of attachment insecurity on relationship satisfaction. To this end, the first section of the Introduction summarizes theory and research, noting that threats to intimacy play an important role in determining whether insecure representations of relationships are activated and thus have implications for the relationship. The second section highlights the intimate nature of sex and accordingly reviews evidence consistent with the possibility that more frequent and/or satisfying sex may provide a level of intimacy that can minimize the extent to which the insecure system gets activated and thus allow both anxiously and avoidantly attached intimates to be more satisfied with their relationships. Finally, the third section provides an overview of two independent studies that examined (a) the number of times newlywed spouses engaged in sex over the past 30 days and (b) whether reports of their daily sexual satisfaction moderated the association between their attachment style and their marital satisfaction, and whether expectancies for the availability of their partners mediated these effects.

Attachment Insecurity, Intimacy, and Relationship Satisfaction

Identifying factors that may protect insecure intimates from the negative implications of their insecure attachment systems requires understanding why insecurely attached individuals struggle to be satisfied in their romantic relationships in the first place. According to Mikulincer and Shaver’s (2003; see also Shaver & Mikulincer, 2002) recent model of attachment system activation, such struggles occur because insecure intimates respond differently than secure intimates to attachment system activation, which inevitably occurs in face of threats (e.g., separation or conflict). Specifically, whereas secure individuals tend to remain relatively satisfied with their relationships under conditions of threat (e.g., Mikulincer, Gillath, & Shaver, 2002; Simpson, Rholes, & Nelligan, 1992), insecure individuals become unhappy under conditions of threat because activation of the attachment system triggers processes that ultimately harm their relationships. For example, because anxiously attached intimates tend to believe their partners might be available, they tend to respond to attachment system activation by becoming hypervigilant to signs of threat and persistently seeking reassurance of a partner’s availability, processes that lead them to be less satisfied (e.g., Collins & Feeney, 2004). In contrast, because avoidantly attached intimates tend to feel rather certain that their partners will not be available, they tend to respond to attachment system activation by withdrawing from their partners and becoming rigidly self-reliant, processes that lead them to be less satisfied as well (e.g., Simpson et al., 1992).

But what if the attachment systems of anxiously and avoidantly attached individuals are not activated in the first place, or activated only infrequently? Although Mikulincer and Shaver’s (2003) model posits that insecure individuals may demonstrate residual habits associated with their attachment orientation under neutral conditions, it suggests that insecure attachment systems are most harmful to their relationship when they are activated. Accordingly, circumstances that inhibit attachment system activation, such as events that lead to feelings of intimacy and diminished threat, may serve as protective factors that buffer insecure intimates from many of the negative implications of their insecure attachment systems. Several studies provide support for this idea among anxiously attached individuals (Carnelley & Rowe, 2007; Mikulincer, Hirschberger, Nachmias, & Gillath, 2001; Rom & Mikulincer 2003). For instance, Rom and Mikulincer (2003) demonstrated that the positive association between individuals’ attachment anxiety and their performance on a group task, performed with an experimental group, was moderated by the perceived cohesion of that group. Specifically, although greater attachment anxiety was associated with poorer performance on the task in less cohesive groups, attachment anxiety was unrelated to performance in more cohesive groups.

What about avoidantly attached individuals? Should circumstances that promote intimacy protect them from the negative implications of their attachments systems as well? Given that avoidant individuals tend to desire less intimacy once their attachment systems are activated, it could be argued that more intimacy would make avoidantly attached intimates less satisfied. Indeed, in one of their studies, Rom and Mikulincer (2003) reported that avoidant individuals performed worse under high group cohesion conditions than under low group cohesion conditions. Likewise, several other studies demonstrate that avoidant intimates respond more negatively to circumstances that promote or raise awareness of intimacy in their close relationships (Birnbaum, Reis, Mikulincer, Gillath, & Orpaz, 2006; Bogaert & Sadava, 2002; Collins & Feeney, 2000; Simpson et al., 1992). However, Mikulincer and Shaver’s (2003) model suggests these responses should be limited to situations in which the avoidant system has already been activated. After all, although they immediately engage in deactivating strategies once their attachment systems are activated, even avoidantly attached intimates appear to desire love and intimacy at the preconscious level (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2002; see also, Mikulincer, Birnbaum, Woddis, & Nachmias, 2000; Mikulincer et al., 2002). Accordingly, in relationships and situations that inhibit the attachment system from being activated in the first place, even avoidant individuals may function similarly to secure individuals.

Attachment Insecurity and Sex

What qualities may lead to the closeness and intimacy necessary to minimize activation of attachment system in established and committed romantic relationships? One behavior that promotes intimacy in such relationships is sex (Regan & Berscheid, 1996; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2006). Indeed, levels of oxytocin are elevated during both sexual arousal (Carmichael et al., 1987) and sexual climax (Carter, 1992), and increased levels of oxytocin have been linked to both pair bonding in animals (e.g., Cho, DeVries, Williams, & Carter, 1999) and perceptions of closeness in humans (Grewen, Girdler, Amico, & Light, 2005). Moreover, merely thinking about sex appears to lead to increased accessibility of intimacy-related thoughts, prorelationship attitudes, and motivations to strengthen existing relationships (Gillath, Mikulincer, Birnbaum, & Shaver, 2008). Accordingly, in line with Mikulincer and Shaver’s (2003) model, insecure intimates who engage in more frequent and/or satisfying sex with their partners may tend to feel high levels of intimacy that may inhibit the activation of insecure attachment representations and allow them to experience levels of relationship satisfaction that are similar to those experienced by secure intimates. Alternatively, insecure intimates who engage in infrequent or unsatisfying sexual intercourse should feel low levels of intimacy that may activate their insecure attachment representations and thus lead to the lower levels of satisfaction with the relationship that are typically observed.

Though we are aware of no research that has addressed this possibility directly, two studies provide some indirect support for it. First, Butzer and Campbell (2008) reported that satisfaction with the sexual relationship moderated the effects of attachment anxiety on relationship satisfaction, such that anxiously attached intimates who reported higher levels of sexual satisfaction also reported higher levels of relationship satisfaction. Second, Birnbaum et al. (2006) reported similar findings using daily reports of specific sexual experiences, demonstrating that anxiously attached intimates who reported positive sexual experiences reported higher levels of relationship satisfaction.

The extent to which these studies support the prediction that frequent and/or quality sex moderates the effects of insecure attachment on relationship satisfaction is limited in two important ways, however. First, neither of these studies reported any evidence that sex can buffer intimates against the negative effects of attachment avoidance. In fact, several studies suggest the opposite may be true, showing that avoidant individuals report more negative motivations for and implications of sex (Birnbaum et al., 2006; Bogaert & Sadava, 2002; Schachner & Shaver, 2004). Nevertheless, as argued previously, these negative experiences with sex may be unique to situations in which the attachment system is likely to be activated. Indeed, all of these studies demonstrated the negative association between attachment avoidance and sex in samples of individuals likely to be experiencing low levels of intimacy and commitment, such as individuals not in committed or established relationships (Birnbaum et al., 2006, Study 1; Bogaert & Sadava, 2002; Schachner & Shaver, 2004) or cohabiting couples who were not married (Birnbaum et al., 2006, Study 2). However, if, as argued previously, more frequent sex in established and committed relationships prevents avoidant attachment representations from being activated in the first place, frequent sex in such relationships may be adaptive even for avoidantly attached intimates.

Second, studies on whether sex moderates the negative effects of attachment insecurity have not examined the mechanism of such effects. A key component of Mikulincer and Shaver’s (2003) model is that once the attachment system is activated, insecure intimates call up their more negative expectancies regarding the availability and responsiveness of their partners—expectancies that lead them to think and behave in relationship-damaging ways. Accordingly, if sex prevents the attachment system from being activated in the first place, one reason insecure intimates who experience more frequent and/or satisfying sex are able to remain more satisfied in their relationships may be that those negative expectancies are less accessible. Although no studies have explored the extent to which sexual behavior can shape such expectancies for the partner’s availability, participants primed to feel more secure do report more positive and fewer negative interpersonal expectancies (Rowe & Carnelley, 2003).

Overview of the Current Research

We used data drawn from two independent studies of newlyweds to test whether couples’ reports of the frequency and quality of their sex moderated the effects of both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on marital satisfaction, and whether those effects were mediated by expectancies for the availability of their partners. Given that the procedures used in each study were nearly identical, we describe both studies simultaneously below. Also, given that the measures used in each study were identical, we analyzed the two samples together but controlled for idiosyncratic differences between them.

Newlyweds are an appropriate sample with which to address these issues for at least three reasons. First, in contrast to prior samples that have included individuals not currently involved in a relationship (Birnbaum et al., 2006, Study 1; Bogaert & Sadava, 2002; Schachner & Shaver, 2004) or couples with potentially unique experiences with commitment (Birnbaum et al., 2006, Study 2), sampling from newlyweds ensured that these couples were in established relationships and, given the proximity of their wedding, likely to be experiencing high levels of commitment. Second, the frequency of sex appears to decline rapidly over the first year of marriage (James, 1981) and thus may be most closely tied to relationship satisfaction during this time. Third, because 20% of couples divorce within the first 5 years of marriage (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002), studying spouses just after the wedding allows researchers to capture important variance by including responses from couples who divorce early.

We tested our predictions in two sets of analyses. In the first set of analyses, we used data from both studies to examine whether reports of the number of times spouses had engaged in sex over the previous 30 days moderated the association between reports of marital satisfaction and reports of both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance, and whether those interactive effects were mediated by spouses’ expectancies regarding their partner’s availability. We predicted that although attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance would be associated with lower levels of marital satisfaction, on average, those associations would be qualified by interactive effects of frequency of sex, such that attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance would be unrelated to marital satisfaction among spouses reporting having engaged in more frequent sex over the past 30 days. Furthermore, given the premise that more frequent sex should have its effects by minimizing attachment system activation, we also predicted that these effects would be mediated by more positive expectancies for partner availability.

In the second set of analyses, we used data from a 7-day diary completed by participants in both studies to examine whether daily reports of sexual satisfaction similarly moderated the association between daily marital satisfaction and attachment insecurity, and whether those interactive effects were mediated by expectancies regarding their partners’ availability. We predicted that although both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance would be associated with lower daily satisfaction with the relationship on average, those associations would be qualified by interactive effects of daily sexual satisfaction, such that attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance would be unrelated to marital satisfaction on days when spouses reported higher levels of sexual satisfaction. Furthermore, given the premise that more satisfying sex should have its effects by minimizing attachment system activation, we also predicted that these effects would be mediated by more positive expectancies for partner availability.

Method

Participants

Participants in Study 1 were 72 newlywed couples recruited from northern Ohio. Participants in Study 2 were 135 newlywed couples recruited from eastern Tennessee.1 Couples in both studies were recruited using two methods. The first was to place advertisements in community newspapers and bridal shops offering payment to couples willing to participate in a study of newlyweds. The second was to send invitations to eligible couples who had completed marriage license applications in counties near study locations. All couples responding to either solicitation were screened for eligibility in an initial telephone interview. Inclusion required that: (a) this was the first marriage for each partner, (b) the couple had been married less than 6 months, (c) each partner was at least 18 years of age, and (d) each partner spoke English and had completed at least 10 years of education (to ensure comprehension of the questionnaires). As part of a larger aim of Study 2 (i.e., to allow a similar probability of transitioning to first parenthood for all couples), that study additionally required that couples did not have children and that wives were not older than 35. Eligible couples were scheduled to attend an initial laboratory session and mailed a packet of survey measures.

Demographic summaries of the participants in both samples are presented in Table 1. As the table reveals, participants were of comparable age across both samples, with both spouses in their mid-20s and husbands being slightly older than wives, on average. Reflecting the education level of each community, participants in Study 1 reported relatively lower levels of education, on average, whereas participants in Study 2 reported relatively higher levels of education, on average. Furthermore, a large proportion of participants in both studies was employed full-time at the beginning of the study, whereas a minority of participants was in school full-time. The median income, combined across spouses, was between $30,000 and $40,000 in each study. Only 10 couples (14%) in Study 1 lived together before marriage whereas 62 couples (56%) in Study 2 lived together before marriage. The majority of participants were Caucasian (> 90%).

Table 1.

Sample Demographics

| Spouse | Age

|

Years of education

|

Full-time employed

|

Full-time students

|

Income group

|

Cohabited

|

Caucasian

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | % | % | Mdn ($000) | SD ($000) | % | % | |

| Study 1 (N = 72) | ||||||||||

| Husbands | 24.92 | (4.39) | 14.15 | (2.48) | 74 | 11 | $15–$20 | ($4.83) | 14 | 93 |

| Wives | 23.54 | (3.85) | 14.72 | (2.24) | 49 | 26 | $15–$20 | ($4.41) | 14 | 96 |

| Study 2 (N = 135) | ||||||||||

| Husbands | 25.90 | (4.57) | 15.69 | (2.38) | 70 | 26 | $20–$25 | ($7.21) | 56 | 91 |

| Wives | 24.21 | (3.59) | 18.14 | (1.88) | 56 | 28 | $10–$15 | ($5.41) | 56 | 93 |

Procedure

Procedures were nearly identical in both studies. As part of a larger study on marital development, couples attended a 3-hour laboratory session. Before the session, they were mailed a packet of questionnaires to complete at home and bring with them to their appointment. This packet included a consent form approved by the university Institutional Review Board, a self-report measure of marital satisfaction, a self-report measure of the number of times the couple had engaged in sexual intercourse over the past 30 days, a self-report measure of attachment anxiety and avoidance, a self-report measure of expectancies for partner availability, and a letter instructing couples to complete all questionnaires independently of one another. After completing their sessions, couples were paid ($60 in Study 1, $80 in Study 2)2 for participating in this phase of each study.

Before leaving the lab, each spouse was provided with seven stamped and addressed envelopes. Each envelope contained a one-page questionnaire that included items designed to assess spouses’ feelings of sexual and relationship satisfaction on the current day, as well as expectancies for how satisfied they would be the following day with their partner’s availability. Couples were paid an additional $25 for completing all 14 diaries, or $1.50 per diary if they failed to return all pages.

Measures

Attachment style

Attachment style was measured in both studies using the Experiences in Close Relationships scale (ECR; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). The ECR measures attachment on two dimensions: Attachment Avoidance and Attachment Anxiety. The Avoidance subscale is derived from 18 items that capture the extent to which spouses attempt to maintain distance from a partner (e.g. “I get uncomfortable when a romantic partner wants to be very close”). The Anxiety subscale is derived from 18 items that describe the degree of concern spouses have about losing a partner or frustration over an inability to become sufficiently close to a partner (e.g. “I worry about being abandoned,” “I find that my partner(s) don’t want to get as close as I would like”). Participants were asked to rate how much they agreed or disagreed with these statements on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = disagree strongly, 7 = agree strongly). Means were formed with higher scores indicating more attachment insecurity. Internal consistency was high in both studies (Study 1: coefficient alphas = .91 for husbands’ anxiety, .92 for wives’ anxiety, .92 for husbands’ avoidance, and .94 for wives’ avoidance; Study 2: coefficient alphas = .91 for husbands’ anxiety, .90 for wives’ anxiety, .91 for husbands’ avoidance, and .88 for wives’ avoidance).

Frequency of sex

Frequency of sex was assessed in both studies with one item that asked each spouse to provide a numerical estimate of the number of times they had engaged in intercourse with their partner in the past 30 days. Because both partners reported on the same behavior, and because individual reports of sexual behavior have been shown to be less reliable in the past (e.g., Jacobson & Moore, 1981), husbands’ and wives’ reports of their frequency of sex were averaged to form an index of couple frequency of sex. Surprisingly, husbands’ and wives’ reports were highly correlated (Study 1: r = .86; Study 2: r = .91). These high correlations may have emerged because the range of reports between couples was large (see Table 2), allowing even raw disagreements between partners to be similar in a relative sense.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Independent Variables

| Measure | Husbands

|

Wives

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Marital satisfaction | ||||

| Study 1 | 40.97 | (4.81) | 41.32 | (5.94) |

| Study 2 | 42.59 | (3.18) | 42.40 | (3.47) |

| Attachment anxiety | ||||

| Study 1 | 2.14 | (0.97) | 2.02 | (0.85) |

| Study 2 | 2.04 | (0.95) | 2.00 | (0.98) |

| Attachment avoidance | ||||

| Study 1 | 2.06 | (0.88) | 1.82 | (0.68) |

| Study 2 | 2.04 | (0.89) | 1.79 | (0.84) |

| Frequency of sex during past 30 days | ||||

| Study 1 | 12.08 | (10.78) | 12.73 | (10.29) |

| Study 2 | 15.79 | (12.71) | 15.38 | (12.12) |

| Availability expectancies | ||||

| Study 1 | 4.40 | (0.69) | 4.43 | (0.60) |

| Study 2 | 4.49 | (0.71) | 4.56 | (0.65) |

| Diary sexual satisfaction | ||||

| Study 1 | 5.39 | (1.49) | 5.30 | (1.24) |

| Study 2 | 5.45 | (1.23) | 5.35 | (1.18) |

| Diary availability expectancies | ||||

| Study 1 | 6.03 | (0.81) | 6.02 | (0.75) |

| Study 2 | 6.67 | (0.71) | 6.11 | (0.71) |

| Diary relationship satisfaction | ||||

| Study 1 | 6.40 | (0.73) | 6.37 | (0.64) |

| Study 2 | 6.37 | (0.61) | 6.32 | (0.67) |

Marital satisfaction

We assessed global marital satisfaction using a version of the Semantic Differential (SMD; Osgood, Suci, & Tannenbaum, 1957). This version of the SMD is a 15-item measure that asks participants to evaluate their relationship according to sets of opposing adjectives (e.g., good–bad, pleasant–unpleasant, satisfying–unsatisfying) on a 7-point scale. Thus, scores on the SMD could range from 15 to 105, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction with the marriage. Internal consistency was high (Study 1: coefficient alphas = .94 for husbands and .94 for wives; Study 2: coefficient alphas = .89 for husbands and .91 for wives).

Expectancies for availability

Given the prediction that the interactive effects of frequency of sex and attachment style would be mediated by expectancies for the partner’s availability, we used two items to assess spouses’ tendencies to hold more or less positive expectancies for their partner’s availability. The first question assessed spouses’ expectancies for how satisfied they would be with the affection in the relationship on a scale from 1 (expect to be not at all satisfied) to 5 (expect to be completely satisfied). The second question assessed spouses’ expectancies for how satisfied they would be with the trust in the relationship on a scale from 1 (expect to be not at all satisfied) to 5 (expect to be completely satisfied). These two items were highly correlated in Study 1 (rs = .53 for husbands and .52 for wives) but only weakly correlated in Study 2 (rs = .18 for husbands and .20 for wives), though both correlations in Study 2 were significant.

Daily sexual satisfaction

Daily sexual satisfaction was assessed in both studies through the following question that appeared daily on the 7-day diary: “Thinking about the past 24 hours, how satisfied were you with your sex life?” on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all satisfied, 7 = extremely satisfied).

Daily relationship satisfaction

Daily satisfaction with the relationship was assessed in both studies through the following three questions modified from the Kansas Marital Satisfaction scale (Schumm et al., 1986) that appeared daily on the 7-day diary: (a) “How satisfied were you with your partner today?” (b) “How satisfied were you with your relationship today?” and (c) “How satisfied were you with your marriage today?” (1 = not at all satisfied, 7 = extremely satisfied). Participants’ daily responses to each item were highly consistent (coefficient alphas ranged from .92 to .97 for husbands and from .89 to .96 for wives), so they were summed to form scores of daily relationship satisfaction for husbands and wives.

Daily expectancies for availability

Given the prediction that the interactive effects of daily sexual satisfaction and attachment style would be mediated by expectancies for the partner’s availability, we used the following four items that also appeared on the 7-day diary to assess spouses’ expectancies for their partners’ availability over “the next 24 hours”: (a) “How satisfied do you expect to be with how affectionate your spouse will be?” (b) “How satisfied do you expect to be with how dependable your spouse will be?” (c) “How satisfied do you expect to be with how your spouse will support you?” and (d) “How satisfied do you expect to be with the amount of time the two of you will spend together?” (1 = not at all satisfied, 7 = extremely satisfied). Participants’ daily responses to each item were highly consistent (coefficient alphas ranged from .73 to .86 for husbands and from .67 to .88 for wives), so they were summed to form scores of daily expectancies for partner availability for husbands and wives.

Analysis Strategy

A set of between-subjects analyses tested the extent to which reports of sexual frequency moderated the extent to which attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were associated with marital satisfaction. Given the nonindependence of husbands’ and wives’ reports, these analyses were conducted in a two-level multilevel model (Bryk & Raudenbush, 2002) using the HLM 6.2 computer program. In the first level, marital satisfaction was regressed onto attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, frequency of sex, the interaction between frequency of sex and attachment anxiety, the interaction between frequency of sex and attachment avoidance, and participant sex. The nonindependence of husbands’ and wives’ data was controlled in the second level with a randomly varying intercept term. Five participants were excluded from these analyses because they failed to properly fill out the marital satisfaction measure. Additionally, a set of within- and between-subjects analyses tested the extent to which daily variation in sexual satisfaction moderated the extent to which attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were associated with daily satisfaction with the relationship, and the extent to which daily expectancies for availability mediated those associations. These analyses were conducted in a three-level multilevel model in which daily relationship satisfaction was regressed onto daily sexual satisfaction and participant sex in the first level, attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were examined as moderators of this association in the second level, and the nonindependence of husbands and wives data was controlled in the third level with a randomly varying intercept term. As mentioned in the Overview, given that the measures used in each study were identical, we analyzed the two samples together but controlled for idiosyncratic differences between the two studies by entering a dummy code for study into the couple level of each analysis (Level 2 in the between-subjects analyses and Level 3 in the within-subjects analyses). Importantly, follow-up analyses indicated that none of the effects varied across study or participant sex.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics for the independent variables for both studies are presented in Table 2. As would be expected in samples of newlyweds, husbands and wives tended to report high levels of satisfaction with their relationships and high expectancies for their partners’ availability, on average. Also not surprisingly, these newlyweds reported relatively high levels of security, with scores similar to those typically found in community samples of adult couples (e.g., Butzer & Camp-bell, 2008). Standard deviations indicated substantial variability across spouses in both samples, however, suggesting some spouses were more anxious and avoidant than others. The average reported frequency of sex was also high, with couples in both studies reporting having had sex almost once every 2 days over the previous 30 days, on average. Nevertheless, there was considerable variability in all those reports as well, as indicated by the substantial standard deviations. In fact, reports ranged from 0 to 90 instances of sex over the past 30 days. Paired samples t tests revealed only one gender difference in these variables: Consistent with other research (see Schmitt et al., 2003), husbands reported significantly more attachment avoidance than wives in both studies: Study 1, t(71) = 2.15, p < .05, and Study 2, t(133) = 2.92, p < .01.

Data obtained from the diary component of both studies are also reported in Table 2. Of the 72 couples in Study 1, 64 (89%) husbands and 64 (89%) wives returned at least two diaries and were thus included in these and subsequent analyses. Of the 135 couples in Study 2, 115 (85%) husbands and 119 (88%) wives returned at least two diaries and were thus included in these and subsequent analyses. Consistent with the global reports of marital satisfaction described previously, these newlyweds were relatively satisfied with their relationships on a daily basis, on average. Likewise, spouses were relatively satisfied with the sexual aspects of their relationships across days, on average. Finally, spouses also tended to hold high expectancies for availability across days, on average. Nevertheless, there was substantial variability in all of these variables, as well. There were no significant differences between husbands and wives in these daily reports.

Correlations among the independent variables are presented in Table 3. Seven results are worth highlighting. First, levels of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were positively correlated with one another within husbands and wives (Study 1: husbands rs = .61 for husbands and .56 for wives; Study 2: rs = .46 for husbands and .51 for wives; all ps < .001), suggesting the need to control each variable to examine the unique effects of avoidance and anxiety in tests of the primary hypotheses. Second, replicating the robust association between insecure attachment and relationship satisfaction, both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were negatively associated with global and daily marital satisfaction within both husbands and wives in both studies. Third, attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance demonstrated a pattern of weak and inconsistent negative associations with both frequency of sex and daily sexual satisfaction. Accordingly, the data should provide a fair test of our hypothesis, as it appears that at least some husbands and wives engaged in frequent or satisfying sex regardless of insecure attachment. Fourth, both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were associated with more negative expectancies about partner availability for husbands and wives in both studies, with the exception that the global measure of expectancies was not associated with wives’ insecurity in Study 1. Fifth, the daily measures were moderately associated with the global measures, suggesting that this was a similar but methodologically distinct way to test the current hypotheses. Sixth, correlations between the demographic factors and frequency of sex indicate that older husbands in both studies, older wives in Study 2, more educated wives in Study 1, employed wives in Study 2, and cohabiting couples in both studies engaged in sex less frequently. Wives who were in school reported having more sex in both studies. Likewise, older husbands in Study 1, employed husbands in Study 1, husbands who made more money in Study 1, and cohabiting husbands and wives in Study 1 reported lower levels of daily sexual satisfaction. Seventh, within studies, correlations between husbands and wives were all positive and statistically significant, with the exception that associations between husbands’ and wives’ employment in Study 1 and their income in Study 2 did not reach significance.

Table 3.

Correlations Among Predictors

| Study 1

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| 1. Marital satisfaction | .37** | −.39*** | −.38*** | .28*** | .34** | .59*** | .52*** | .44*** | .14 | .12 | .07 | .05 | .17† | −.25* |

| 2. Attachment anxiety | −.30** | .20* | .56*** | −.05 | −.06 | −.36** | −.24* | −.27* | .16† | −.09 | .07 | −.09 | −.08 | .08 |

| 3. Attachment avoidance | −.16† | .61*** | .29** | .09 | −.07 | −.46*** | −.26* | −.42*** | .27* | .11 | .02 | −.04 | .14 | .23* |

| 4. Frequency of sex | −.02 | −.11 | −.24* | 1.00 | .07 | .06 | .43*** | .14 | −.15 | −.04 | −.12 | .22* | −.14 | −.24* |

| 5. Expectancies | .45*** | −.31** | −.24* | .04 | .22* | .28* | .31** | .22* | .03 | −.18† | −.04 | −.08 | −.16 | .02 |

| 6. Daily marital satisfaction | .76*** | −.35** | −.35** | .01 | .64*** | .75*** | .41*** | .67*** | −.11 | .05 | .10 | .26* | .03 | −.14 |

| 7. Daily sexual satisfaction | .45*** | −.23* | −.08 | .33** | .40*** | .58*** | .68*** | .71*** | −.15 | −.07 | −.13 | .03 | .06 | −.34** |

| 8. Daily expectancies | .57*** | −.19† | −.18† | .05 | .60*** | .78*** | .76*** | . 65*** | −.18† | −.06 | −.06 | .05 | −.05 | −.28* |

| 9. Age | −.17† | .02 | .09 | −.19† | −.18† | −.20† | −.18† | −.29* | .62*** | .37** | .20* | −.30* | .60*** | −.07 |

| 10. Years of education | −.01 | −.10 | −.09 | −.17† | −.10 | −.08 | −.09 | −.09 | .21* | .43** | .06 | .11 | .58*** | −.01 |

| 11. Employed now | −.15 | −.01 | −.14 | −.04 | −.24* | −.26* | −.34*** | −.34** | −.10 | .21* | −.03 | −.18† | .31** | .19† |

| 12. In school now | .10 | −.03 | .01 | .01 | −.12 | .15 | −.06 | .02 | .19† | .27* | .09 | .24* | −.30** | −.03 |

| 13. Income category | −.08 | .03 | −.19 | −.22* | −.19† | −.10 | −.33** | −.26* | .46*** | .29** | .31** | −.01 | .31** | .10 |

| 14. Cohabited | −.04 | .12 | .13 | −.20* | −.23* | −.08 | −.22* | −.18† | −.16† | −.27* | −.01 | .03 | −.02 | 1.00 |

| Study 2

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| 1. Marital satisfaction | .32*** | −.23** | −.24** | .22** | .44*** | .55*** | .40*** | .52*** | −.10 | −.05 | −.09 | .13† | .07 | −.02 |

| 2. Attachment anxiety | −.25** | .42*** | .51*** | −.13† | −.35*** | −.22** | −.26** | −.32*** | .08 | .01 | −.04 | −.11 | −.06 | .07 |

| 3. Attachment avoidance | −.24** | .46*** | .26** | −.05 | −.20** | −.19* | −.17* | −.26** | .14† | .07 | −.09 | −.07 | −.09 | .05 |

| 4. Frequency of sex | .17* | −.19* | −.26** | 1.00 | .24** | .11 | .32*** | .26** | −.33*** | −.20* | −.33*** | .17* | .09 | −.39*** |

| 5. Expectancies | .38*** | −.22** | −.30*** | .19* | .44*** | .32*** | .29** | .40*** | −.06 | −.14† | .06 | .19* | .06 | −.08 |

| 6. Daily marital satisfaction | .41*** | −.14† | −.13† | .05 | .38*** | .57*** | .50*** | .65*** | .03 | .02 | .05 | .04 | .09 | .09 |

| 7. Daily sexual satisfaction | .32*** | −.26** | −.38*** | .28** | .35*** | .50*** | .41*** | .70*** | −.10 | −.08 | .05 | .13 | .12 | −.04 |

| 8. Daily expectancies | .51*** | −.18* | −.22** | .20* | .43*** | .74*** | .72*** | .55*** | −.11 | −.13† | .03 | .15† | .09 | .01 |

| 9. Age | −.10 | .04 | .04 | −.26** | −.03 | −.10 | −.11 | −.05 | .69*** | .56*** | .21** | −.21** | −.06 | .13 |

| 10. Years of education | −.03 | −.18* | −.03 | −.01 | −.01 | −.07 | −.09 | −.06 | .40*** | .47*** | .07 | .07 | −.14 | −.07 |

| 11. Employed now | −.04 | −.09 | −.06 | .01 | .01 | .12 | .10 | .09 | −.06 | .07 | .16* | −.26** | .05 | .06 |

| 12. In school now | .04 | −.05 | .01 | −.03 | .12 | .01 | .03 | −.02 | −.15* | .25** | −.05 | .22** | −.08 | −.06 |

| 13. Income category | .11 | .14† | .02 | −.03 | .09 | .10 | .02 | .16* | −.14* | −.12† | .05 | .06 | −.02 | −.09 |

| 14. Cohabited | .18* | .19* | .15* | −.31*** | −.10 | .16* | −.09 | .09 | .16* | −.17* | −.02 | −.04 | −.02 | 1.00 |

NOTE: Wives’ correlations appear above the diagonal, husbands’ correlations appear below the diagonal, and correlations between husbands and wives appear on the diagonal in bold.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Did Frequency of Sex Moderate the Effects of Attachment Insecurity on Marital Satisfaction?

The first set of analyses examined whether frequency of sex moderated the robust negative effects of attachment insecurity on global marital satisfaction. We conducted one analysis in pursuit of this goal, collapsing across but controlling for study and participant sex. In the first level of a multilevel model, we regressed marital satisfaction onto a mean-centered attachment anxiety score, a mean-centered attachment avoidance score, a mean-centered frequency of sex score, the product of the mean-centered anxiety and frequency scores, the product of the mean-centered avoidance and frequency scores, and a dummy code representing sex. In the second level of the model that controlled for the nonindependence of husbands’ and wives’ data, we regressed the average level of couples’ satisfaction onto a dummy code representing cohabitation, a dummy code representing study, and a random effect. Notably, follow-up analyses revealed that none of the significant effects varied significantly across participant sex or study.

The results of the analysis are reported in Table 4.3 As seen there, consistent with predictions, a significant positive interaction emerged between frequency of sex and attachment avoidance. Notably, although the Frequency of Sex × Attachment Anxiety interaction did not reach significance once the interactive effect of attachment avoidance was controlled, the magnitude of that effect did not differ from the magnitude of the Frequency of Sex × Attachment Avoidance interaction, χ2(1) = 0.27, p > .50.4

Table 4.

Interactions Between Attachment Insecurity and Reports of Sexual Frequency Predicting Marital Satisfaction

| B | SE | Effect size r | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 96.67 | 0.44 | — |

| Study | 2.33 | 1.20 | .14† |

| Cohabitation | 1.48 | 0.97 | .11 |

| Sex | 0.87 | 0.88 | .05 |

| Anxiety | −1.04−1 | 0.31−1 | −.17** |

| Avoidance | −0.74−1 | 0.31−1 | −.12* |

| Frequency of sex | 1.22−1 | 0.29−1 | .21*** |

| Attachment Anxiety × Frequency | 2.27−3 | 2.74−3 | .04 |

| Attachment Avoidance × Frequency | 4.16−3 | 1.94−3 | .11* |

NOTE: For study and cohabitation, dfs = 200. For all variables, dfs = 392. ‘

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

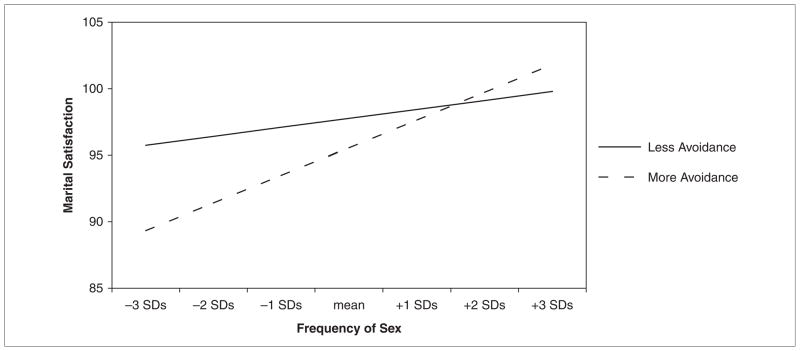

To determine the nature of the significant Frequency of Sex × Attachment Avoidance interaction, it was deconstructed by plotting the predicted means of marital satisfaction for participants who were 1 SD above and below the mean on attachment avoidance and at the various levels of sexual frequency within the sample—up to ±3 SD. The result of that plot appears in Figure 1. As the plot reveals, consistent with predictions, the association between attachment avoidance and marital satisfaction was most pronounced among spouses reporting relatively low frequency of sex, whereas that association became less pronounced as spouses experienced more sex in their relationships. In fact, identifying the regions of significance using procedures outlined by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006) revealed that attachment avoidance was unassociated with marital satisfaction among spouses who reported more than 0.37 SD more frequent sex than the average.

Figure 1.

Interaction between frequency of sex and attachment avoidance accounting for marital satisfaction

Were the Interactive Effects of Sexual Frequency and Attachment Insecurity on Marital Satisfaction Mediated by Expectancies for the Partner’s Availability?

Given our premise that more frequent sex would help buffer intimates from the negative implications of their insecure attachment systems by inhibiting attachment system activation, we predicted that the interactive effects of frequency of sex and attachment avoidance would be mediated by their expectancies for the partner’s availability. We tested for mediation by computing asymmetric confidence intervals for the mediated effect following the procedures described by MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, and Lockwood (2007). Those procedures required two sets of additional analyses. First, we estimated the interactive effects of sexual frequency and attachment avoidance on the expected mediator, expectancies for availability, by repeating the analyses described previously, substituting expectancies for availability for marital satisfaction as the dependent variable. Indeed, frequency of sex marginally moderated the effects of attachment avoidance on expectancies for availability, B = 2.00−4, SE = 1.16−4, t(392) = 1.72, p = .09, r = .09. Notably, frequency of sex also moderated the effect of attachment anxiety on availability expectancies, B = 2.15−4, SE = 1.04−4, t(392) = 2.08, p < .05, r = .10. Neither of these effects varied in strength across participant sex or across the two studies. Second, we estimated the association between expectancies for availability and marital satisfaction, controlling for the interactive effects of sexual frequency and both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. Indeed, expectancies for availability were associated with marital satisfaction, B = 6.60, SE = 1.21, t(391) = 5.43, p < .001, r = .27. This effect did not vary across participant sex or study. Finally, we multiplied these two effects together to obtain an estimate of the mediated effect (B = 1.32−3) and computed the corresponding 90% confidence interval (8.00−5:2.70−3) that indicated the mediated effect was marginally significant.

Did Daily Sexual Satisfaction Moderate the Association Between Attachment Style and Daily Satisfaction With the Relationship?

Next, we analyzed whether the same interactive pattern between sex and attachment style that emerged in the between-subjects analysis described previously also emerged within people over the 1-week course of the diary. Specifically, we estimated the within-subjects association between daily sexual satisfaction and daily relationship satisfaction in the first level of a multilevel model. Then, in the second level of the model, we simultaneously estimated the extent to which attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance interacted with that association, controlling for the effects of each attachment variable and participant sex on daily relationship satisfaction. Finally, as was the case in the between-subjects analyses reported previously, we controlled for study and cohabitation by entering a dummy code of each variable to account for variance in average level of satisfaction in the third level of the model. Notably, follow-up analyses revealed that none of the significant effects varied significantly across participant sex or study.

The results of this analysis are reported in Table 5. As can be seen there, daily sexual satisfaction interacted with the association between attachment anxiety and daily relationship satisfaction. Notably, although the interactive effects of sexual satisfaction and attachment avoidance did not reach significance once the interactive effect of attachment anxiety was controlled, the magnitude of that effect did not differ from the magnitude of the Sexual Satisfaction × Attachment Anxiety interaction, χ2(1) = 0.37, p > .50.5

Table 5.

Interactions Between Attachment Insecurity and Daily Diary Reports of Sexual Satisfaction Predicting Marital Satisfaction

| B | SE | Effect size r | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 6.29 | 0.05 | — |

| Study | 4.74−2 | 5.94−2 | .06 |

| Cohabitation | 0.12 | 0.06 | .16* |

| Sex | 3.39−2 | 3.47−2 | .05 |

| Anxiety | −5.61−3 | 1.89−3 | −.15** |

| Avoidance | −6.72−3 | 2.26−3 | −.15** |

| Daily sexual satisfaction | 2.26−1 | 0.19−1 | .52*** |

| Attachment Anxiety × Sexual Satisfaction | 1.97−3 | 0.97−3 | .10* |

| Attachment Avoidance × Sexual Satisfaction | 0.83−3 | 1.28−3 | .03 |

NOTE: For study and cohabitation, dfs = 187. For sex, anxiety, and avoidance, dfs = 373. For daily sexual satisfaction, Attachment Anxiety × Sexual Satisfaction, and Attachment Avoidance × Sexual Satisfaction, dfs = 374.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

To determine the nature of the Sexual Satisfaction × Attachment Anxiety interaction, it was deconstructed by plotting the predicted means of daily relationship satisfaction for participants who were 1 SD above and below the mean on attachment anxiety and at the various levels of sexual satisfaction within the sample—up to ±3 SD. The result of that plot appears in Figure 2. As the plot reveals, consistent with predictions, and as was found regarding attachment avoidance in the between-subjects analysis, the association between attachment anxiety and marital satisfaction was most pronounced on days that spouses reported relatively low sexual satisfaction, whereas that association became less pronounced on days that spouses reported greater sexual satisfaction. In fact, identifying the regions of significance using procedures outlined by Preacher et al. (2006) revealed that attachment anxiety was unassociated with marital satisfaction on days that spouses reported sexual satisfaction that was greater than 0.75 SD above the mean.

Figure 2.

Interaction between daily sexual satisfaction and attachment anxiety accounting for daily marital satisfaction

Were the Interactive Effects of Daily Sexual Satisfaction on Daily Relationship Satisfaction Mediated by Daily Expectations for the Partner’s Availability?

Finally, as we did regarding the between-subjects effects for avoidance, we tested whether expectancies for partner availability mediated the interactive effects of sexual satisfaction and attachment anxiety. First, we conducted analyses to estimate the interactive effects of daily sexual satisfaction and attachment anxiety on the expected mediator, daily expectancies for partner availability, but this time substituted daily expectancies for daily satisfaction as the dependent variable. Indeed, sexual satisfaction interacted with the association between attachment anxiety and expectancies for availability, B = 2.67−3, SE = 0.96−3, t(374) = 2.77, p < .01, r = .14, but not attachment avoidance, B = −0.60−3, SE = 0.93−3, t(374) = −0.65, p > .50, r = .03. Notably, these effects did not vary in strength across participant sex or across the two studies. Second, we estimated the association between daily expectancies for availability and daily relationship satisfaction, controlling for the interactive effects of sexual satisfaction and both forms of attachment insecurity. Indeed, daily expectancies for availability were associated with daily relationship satisfaction, B = 5.04−1, SE = .34−1, t(376) = 14.01, p < .001, r = .59. This effect did not vary across participant sex or study. Finally, we multiplied these two effects together to obtain an estimate of the mediated effect, B = 1.35−3, and computed the corresponding 95% confidence interval (4.00−4:2.33−3) that indicated the mediated effect was significant. Notably, once expectancies for availability were controlled, the interaction between sexual satisfaction and attachment anxiety failed to reach significance, B = .001, SE = .49−3, t(374) = 0.53, p > .50, suggesting that expectancies for availability fully mediated the interactive effects of attachment anxiety and daily sexual satisfaction on daily global satisfaction.

Discussion

Study Rationale and Summary of Results

Owing to Karney and Bradbury’s (1995) vulnerability–stress–adaptation model of relationships and Mikulincer and Shaver’s (2003) model of attachment system activation, the current studies tested the prediction that more frequent and satisfying sex can buffer intimates from the negative implications of attachment insecurity. Consistent with those predictions, although both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were negatively associated with marital satisfaction, on average, attachment avoidance was unrelated to marital satisfaction among spouses reporting more frequent sex, and attachment anxiety was unrelated to daily marital satisfaction on days that spouses reported more satisfying sex. Furthermore, consistent with the premise that frequent and/or quality sex should buffer spouses against the negative effects of attachment insecurity by inhibiting the activation of the attachment system in the first place, the interactive effects of attachment insecurity and sex were mediated by expectancies for greater availability of the partner—expectancies that would be unlikely among insecure intimates with activated attachment systems. Lending confidence to these findings, neither varied across husbands or wives or across two independent studies, each emerged in conceptually similar but empirically distinct analyses, and both emerged controlling for whether couples cohabited before marriage.

A few inconsistencies did emerge, however. In the between-subjects analysis that examined the interactive association between frequency of sex and attachment insecurity on marital satisfaction, the number of times couples had engaged in sexual intercourse over the past 30 days only moderated the effects of attachment avoidance on marital satisfaction; the interactive effect of frequency of sex and attachment anxiety did not reach significance. Likewise, in the within-subjects analysis that examined the interactive association between daily sexual satisfaction and attachment insecurity on daily marital satisfaction, daily sexual satisfaction only moderated the effects of attachment anxiety on daily global satisfaction; the interactive effect of daily sexual satisfaction and attachment avoidance did not reach significance. Nevertheless, the two interactive effects did not differ from one another statistically and both interactive effects emerged in both sets of analyses when each interactive effect was estimated separately (see Notes 4 and 5).

Directions for Future Research

The fact that each interactive effect was particularly robust in different analyses does suggest a direction for future research, however. Specifically, this result suggests that there may be something unique about frequent sex that is particularly adaptive for avoidantly attached intimates and something unique about satisfying sex that is particularly adaptive for anxiously attached intimates. In line with Bartholomew and Horowitz’s (1991) distinction between anxiously attached intimates’ negative views of self and avoidantly attached intimates’ negative views of others, perhaps satisfying sex helps anxious intimates feel more positively about the self and frequent sex helps avoidant intimates feel more positively about their partners. Although, as noted previously, the two studies described here did not provide any strong evidence for this possibility, in that the interactive effects of frequency and daily satisfaction did not differ from one another statistically. Other research has found that sexual satisfaction moderates the association between attachment anxiety and relationship satisfaction but not the association between attachment avoidance and relationship satisfaction (see Butzer & Campbell, 2008). Future research may benefit by addressing the possible distinction between frequent and satisfying sex for anxiously and avoidantly attached intimates.

Future research may also benefit by examining whether various qualities of sex further moderate the effects that emerged here. For example, the different motivations underlying sexual behavior may determine whether sex benefits or harms the relationships of insecure intimates. Given that all the couples examined here were newlyweds, both members of the couples investigated in these two studies may have been particularly likely to have engaged in sex for more intimate reasons (e.g., to express passion, experience closeness), on average, which may explain the interactions that emerged in the current work. Intimates who engage in nonintimate sex (e.g., coerced sex, sex to enhance self-esteem, sex to fulfill nonintimate desires) may not experience the same benefits. Indeed, research on couples not limited to the newlywed stage of their relationships suggests that avoidantly attached intimates are more likely to engage in such nonintimate sex (e.g., Schachner & Shaver, 2004), which may differentially affect their satisfaction with the relationship (Butzer & Campbell, 2008). Accordingly, future research may benefit by examining various factors that may determine whether sex promotes or undermines intimacy and thus the direction in which it moderates the effects of attachment insecurity on relationship satisfaction, such as who initiated the sex, intimates’ body positions during the sex (e.g., face-to-face vs. not), whether the sex included foreplay, and the length of the sexual encounter.

Theoretical and Methodological Implications

The findings reported here have several theoretical implications. First, in line with Mikulincer and Shaver’s (2003) model, the current findings join others (Rom & Mikulincer, 2003) in suggesting that factors that enhance feelings of intimacy may prevent the attachment system from being activated and thus buffer intimates from the negative implications of attachment insecurity. Consistent with this possibility, the effects were mediated by one likely consequence of an inactive insecure attachment system, positive expectancies for the availability of the partner, and they emerged among not only anxiously attached spouses but also among avoidantly attached spouses. Although anxiously attached intimates should respond positively to intimacy regardless of attachment system activation, avoidantly attached intimates should only respond positively to sex when the attachment system has not been activated. Indeed, other studies have suggested that sex can be harmful to avoidantly attached intimates (Birnbaum et al., 2006), presumably in conditions when the attachment system is activated (e.g., less intimate sex, sex outside of a close relationship). Future research may benefit from examining other factors that protect insecure intimates from the negative implications of their attachment styles by promoting intimacy (e.g., hugging, kissing, handholding, and support).

Second, the current findings also met Fraley and Shaver’s (2000) recent call for research integrating the attachment system and the sexual system. Such an integration makes sense given that both systems likely evolved to promote gene survival (Bowlby, 1969/1982; Diamond, 2003; Eagle, 2007; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2006); the sexual system evolved to pass genes from one generation to the next (Buss & Kenrick, 1998) and the attachment system likely evolved to maintain necessary physical and emotional closeness with supportive others (Bowlby, 1969/1982; Diamond, 2003). In fact, the similarity of these evolutionary goals suggests that behaviors that satisfy the needs of one system may also satisfy the needs of the other system. Consistent with this idea, the current research demonstrates that behaviors that satisfy the needs of the sexual system, such as frequent and quality sex (see Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 1997), can help satisfy the needs of the attachment system by helping insecure spouses expect their partners to be more available and thus feel more satisfied in their marriages. Likewise, other research suggests that factors that satisfy the needs of the attachment system, such as greater satisfaction with the relationship, can help satisfy the needs of the sexual system (see Lawrance & Byers, 1995). Of course, although they evolved for similar reasons, the sexual and attachment systems did not evolve for the same reason (Bowlby, 1969/1982; Diamond, 2003). Accordingly, behaviors that satisfy one system may not always satisfy the other system. Indeed, as described throughout this article, other work suggests that insecurely attached intimates sometimes have trouble integrating sex and attachment needs (Birnbaum, 2007; Butzer & Campbell, 2008; Eagle, 2007; see also Mikulincer et al., 2002). Given that research demonstrating insecure individuals’ difficulties integrating the two systems has relied on samples containing intimates not in committed and established relationships, and given that the current work using newlyweds demonstrated that sex benefited both anxiously and avoidantly attached spouses, one factor that may determine the feasibility of integrating the two systems may be the level of intimacy or commitment in the relationship. Future work may benefit by examining the extent to which commitment and other factors help insecure intimates integrate the sexual and attachment systems.

Finally, the possibility that commitment may moderate the interactive effects that emerged here suggests an important methodological implication for future work. Specifically, researchers may benefit by considering the various commitment levels of the participants in the samples they use, either by using samples of similarly committed intimates or by examining the moderating role of commitment in more heterogeneous samples. Indeed, recent research demonstrated that whether attachment-related processes such as behavior (McNulty & Russell, in press), attributions (McNulty, O’Mara, & Karney, 2008), and expectancies (McNulty & Karney, 2004) lead to positive or negative outcomes depends on the broader context of a relationship.

Study Strengths, Limitations, and Caveats

Our confidence in the findings reported here is enhanced by several strengths of the research. First, the findings emerged in two conceptually similar but empirically distinct analyses and did not vary across participant sex, anxious or avoidant attachment styles, or two independent studies, suggesting they are robust. Second, both studies controlled for the nonindependence of couples’ data and the autocorrelation due to the repeated assessments in the diary using multilevel modeling, thus reducing the likelihood that the significant effects emerged because of inaccurate estimates of the error terms. Finally, both studies sampled from newlyweds, which allowed us to assess both couples who will remain married and those who will eventually divorce.

Despite these strengths, several qualities of this research limit interpretations and the generalizations of the present findings until they can be expanded. First, these data are correlational, and thus causal conclusions regarding the direction of these effects should be made with caution. Although experimental replication of the effects may not be feasible, research manipulating other intimacy-related behavior may provide stronger evidence that intimacy reduces the activation of insecure attachment representations. Second, although the fact that frequent and/or quality sex was beneficial to both anxiously and avoidantly attached intimates suggests that sex operated by inhibiting activation of the attachment system, our measure of attachment system activation—expectancies for availability—was indirect. Future research may benefit by more directly assessing whether the attachment system is activated versus not activated among intimates engaged in frequent and satisfying versus infrequent and less satisfying sexual activity with their partners. Third, although the homogeneity of our samples helped minimize the influence of variables outside the scope of the current research, such homogeneity limits generalizability of these findings. Specifically, in addition to being limited to noncoerced, intimacy-enhancing sex with an established partner, as noted previously, the benefits of sex to insecurely attached intimates may be limited to newer marriages, as sex declines substantially over the first year of marriage (James, 1981) and thus may become less important to the relationship. Future research may benefit by attempting to examine whether relationship status or length of relationship moderates any of the effects that emerged here.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Letitia Clarke, Timothy Dove, Kendra Krichbaum, Kevin McFarland, Lynn Ousley, Jennifer Schurman, Lindsay Smouther, Corwin Thompson, Renee Vidor, Karen Walters, and Danielle Wentworth for their assistance in data collection in Study 1, and Levi Baker, Katie Fitzpatrick, Kelsey Kennedy, Ian Saxton, and Carolyn Wenner for their assistance in data collection and data entry in Study 2.

Funding

The authors received the following financial support for their research and/or authorship of this article: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant RHD058314 and a Seed Grant Award from The Ohio State University, Mansfield, to James K. McNulty.

Footnotes

Data from Study 1 have been described in several articles (Fisher & McNulty, 2008; Frye, McNulty, & Karney, 2008; McNulty, 2008a, 2008b; McNulty & Fisher, 2008), but there has been little overlap between the variables examined in these articles and the variables examined here. The one exception is that the sexual frequency data were related to sexual satisfaction in McNulty and Fisher (2008). That report did not examine attachment style.

Participants in Study 2 were paid more to account for additional tasks completed. Specifically, whereas the participants in Study 1 completed two problem-solving discussions, participants in Study 2 completed two problem-solving discussions and two social support discussions.

Although the Frequency of Sex × Attachment Anxiety interaction did not reach significance in the analysis that controlled for the Frequency of Sex × Attachment Avoidance interaction, a significant and positive Frequency of Sex × Attachment Anxiety interaction was marginally significant with a one-tailed test in a separate analysis that did not control for the Frequency of Sex × Attachment Avoidance interaction but did control for the avoidance main effect, B = 4.09−3, SE = 2.75−3, t = 1.49, p = .07, one-tailed.

Although the Sexual Satisfaction × Attachment Avoidance interaction did not reach significance in the analysis that controlled for the Sexual Satisfaction × Attachment Anxiety interaction, a marginally significant positive Sexual Satisfaction × Attachment Avoidance interaction was significant with a one-tailed test in a separate analysis that did not control for the Sexual Satisfaction × Attachment Anxiety interaction but did control for the anxiety main effect, B = 1.98−3, SE = 1.18−3, t = 1.67, p < .05, one-tailed.

Reprints and permission: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflict of Interests

The authors had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

References

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum GE. Attachment orientations, sexual functioning, and relationship satisfaction in a community sample of women. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum GE, Reis HT, Mikulincer M, Gillath O, Orpaz A. When sex is more than just sex: Attachment orientations, sexual experience, and relationship quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:929–943. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert AF, Sadava S. Adult attachment and sexual behavior. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1982. (Original work published 1969) [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. Vital Health Statistics, Series 23, No. 2. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. Cohabitation, marriage, divorce and remarriage in the United States. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford; 1998. pp. 394–428. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM, Kenrick DT. Evolutionary and social psychology. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of social psychology. Vol. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 982–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Butzer B, Campbell L. Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships. 2008;15:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael MS, Humbert R, Dixen J, Palmisano G, Greenleaf W, Davidson JM. Plasma oxytocin increases in the human sexual response. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1987;64:27–31. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnelley KB, Rowe AC. Repeated priming of attachment security influences later views of self and relationships. Personal Relationships. 2007;14:307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS. Oxytocin and sexual behavior. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1992;16:131–144. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Shaver PR. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cho MM, DeVries CA, Williams JR, Carter SC. The effects of oxytocin and vasopressin on partner preferences in male and female prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Behavioral Neuroscience. 1999;113:1071–1079. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.5.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Feeney BC. A safe haven: An attachment theory perspective on support seeking and caregiving in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:1053–1073. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Feeney BC. Working models of attachment shape perceptions of social support: Evidence from experimental and observational studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:363–383. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. What does sexual orientation orient? A biobehavioral model distinguishing romantic love and sexual desire. Psychological Review. 2003;110:173–192. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.110.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle M. Attachment and sexuality. In: Diamond D, Blatt S, Lichtenberg JD, editors. Attachment and sexuality. New York: Analytic Press; 2007. pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher TD, McNulty JK. Neuroticism and marital satisfaction: The mediating role played by the sexual relationship. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:112–122. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General Psychology. 2000;4:132–154. [Google Scholar]

- Frye NE, McNulty JK, Karney BR. How do constraints on leaving a marriage affect behavior within the marriage? Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:153–161. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillath O, Mikulincer M, Birnbaum GE, Shaver PR. When sex primes love: Subliminal sexual priming motivates relationship goal pursuit. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34:1057–1069. doi: 10.1177/0146167208318141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewen KM, Girdler SS, Amico J, Light KC. Effects of partner support on resting oxytocin, cortisol, norepinephrine, and blood pressure before and after warm partner contact. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67:531–538. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000170341.88395.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haavio-Mannila E, Kontula O. Correlates of increased sexual satisfaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1997;26:399–419. doi: 10.1023/a:1024591318836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Moore D. Spouses as observers of the events in their relationships. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;49:269–277. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James WH. The honeymoon effect on marital coitus. Journal of Sex Research. 1981;17:114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrance K, Byers ES. Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Personal Relationships. 1995;2:267–285. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK. Neuroticism and interpersonal negativity: The independent contributions of behavior and perceptions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008a;34:1439–1450. doi: 10.1177/0146167208322558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK. Forgiveness in marriage: Putting the benefits into context. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008b;22:171–175. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Fisher TD. Gender differences in response to sexual expectancies and changes in sexual frequency: A short-term longitudinal investigation of sexual satisfaction in newly married heterosexual couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:229–240. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Karney BR. Positive expectations in the early years of marriage: Should couples expect the best or brace for the worst? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:729–743. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, O’Mara EM, Karney BR. Benevolent cognitions as a strategy of relationship maintenance: Don’t sweat the small stuff … but it’s not all small stuff. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:631–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Russell VM. When “negative” behaviors are positive: A contextual analysis of the long-term effects of problem-solving behaviors on changes in relationship satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0017479. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Birnbaum G, Woddis D, Nachmias O. Stress and accessibility of proximity-related thoughts: Exploring the normative and intraindividual components of attachment theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:509–523. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Gillath O, Shaver PR. Activation of the attachment system in adulthood: Threat-related primes increase the accessibility of mental representations of attachment figures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:881–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Hirschberger G, Nachmias O, Gillath O. The affective component of the secure base schema: Affective priming with representations of attachment security. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:305–321. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic; 2003. pp. 53–152. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. A behavioral systems perspective on the psychodynamics of attachment and sexuality. In: Diamond D, Blatt S, Lichtenberg JD, editors. Attachment and sexuality. New York: Analytic Press; 2007. pp. 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood CE, Suci GJ, Tannenbaum PH. The measurement of meaning. Champaign: University of Illinois Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Regan PC, Berscheid E. Beliefs about the state, goals, and objects of sexual desire. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 1996;22:110–120. doi: 10.1080/00926239608404915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rom E, Mikulincer M. Attachment theory and group processes: The association between attachment style and group-related representations, goals, memories, and functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1220–1235. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. Essential of behavioral research: Methods and data analysis. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe AC, Carnelley KB. Attachment style differences in the processing of attachment-relevant information: Primed-style effects on recall, interpersonal expectations, and affect. Personal Relationships. 2003;10:59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Schachner DA, Shaver PR. Attachment dimensions and sexual motives. Personal Relationships. 2004;11:179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt DP, Alcalay L, Allensworth M, Allik J, Ault L, Auster I, et al. Are men more universally dismissing than women? Gender differences in romantic attachment across 62 cultural regions. Personal Relationships. 2003;10:307–331. [Google Scholar]

- Schumm WR, Paff-Bergen LA, Hatch RC, Obiorah FC, Copeland JM, Meens LD, et al. Concurrent and discriminant validity of the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1986;48:381–387. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. Attachment-related psycho-dynamics. Attachment and Human Development. 2002;4:133–161. doi: 10.1080/14616730210154171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. A behavioral systems approach to romantic love relationships: Attachment, caregiving, and sex. In: Sternberg RJ, Weis K, editors. The psychology of love. 2. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2006. pp. 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Collins AW, Tran S, Haydon KC. Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:355–367. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Nelligan JS. Support seeking and support giving within couples in an anxiety-provoking situation: The role of attachment styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:434–446. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Phillips D. Conflict in close relationships: An attachment perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:899–914. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.5.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]