Abstract

AIM: To compare the need for infliximab dose intensification in two cohorts of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC).

METHODS: Single centre, uncontrolled, observational study. Consecutive patients with CD and UC who responded to infliximab induction doses were included. Data collected in a prospectively maintained database were retrospectively analysed. Differences in the rates of dose intensification per patient-month and the intensification-free survival time were compared. We also evaluated the interval between the first infliximab induction dose and the first infliximab escalated dose. The weight-adjusted infliximab administration costs were also calculated.

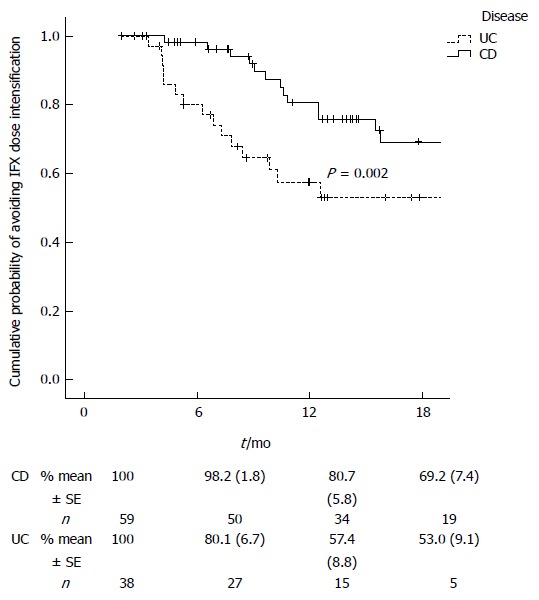

RESULTS: Fifty nine patients with CD and 38 patients with UC were enrolled. The rate of intensification per patient-month was 3.9% for UC and 1.4% for CD (P = 0.005). The median time from baseline to intensification was significantly shorter in UC compared to CD [6.6 mo (IQR: 4.2-9.5 mo) vs 10.7 mo (IQR: 8.9-11.7 mo), P = 0.005]. In the survival analysis, the cumulative probability of avoiding infliximab dose intensification was significantly higher in CD (P = 0.002). In the multivariate analysis, disease (UC vs CD) was the only factor significantly associated with dose intensification. The infiximab administration costs during the first year were significantly higher for UC compared to CD (mean ± SD 234.9 ± 53.3 Euros/kg vs 212.3 ± 15.1 Euros/kg, P = 0.03).

CONCLUSION: The rate of infliximab dose intensification per patient-month is significantly higher in UC patients. The infliximab administration costs are also significantly higher in patients with UC.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, Infliximab, Dose intensification, Costs

Core tip: Infliximab dose intensification to counteract loss of response is well established in the management of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD). In ulcerative colitis, the need for infliximab dose intensification is less well established. The study compares for the first time the need for infliximab dose intensification for ulcerative colitis and CD in the same clinical setting. The need for infliximab dose intensification was significantly higher in patients with ulcerative colitis compared to patients with Crohn’s disease. The drug administration costs were also higher in patients with ulcerative colitis. Our data provide a rational basis for economic planning in patients with ulcerative colitis selected for anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Infliximab is a monoclonal antibody that targets tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and it is indicated for Crohn’s disease (CD) and moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis (UC), among other conditions[1]. In the pivotal clinical trials of infliximab in CD, patients were randomized to placebo, 5 or 10 mg/kg maintenance dosing after an initial response[2,3]. In the ACCENT I trial for luminal CD, dose intensification was allowed in patients who had lost response during maintenance therapy. An analysis of the results of this trial showed that approximately 90% of those in the 5 mg/kg maintenance arm and 80% of those in the 10 mg/kg maintenance arm re-established response on switching to a higher dose (10 and 15 mg/kg), respectively[4]. In the case of UC, the pivotal studies used for approval did not allow dose intensification on loss of response during maintenance[5]. Although the pivotal clinical trials provide less support for dose intensification in UC, in clinical practice, the need for infliximab dose intensification as a result of loss of response has been reported by a number of authors[6-10].

In a systematic review in CD patients, the annual risk of loss of infliximab response and need for infliximab dose intensification was consistently established at around 13% per patient-year[11]. In UC patients the need for infliximab dose intensification is less well defined.

No studies have directly compared the need for dose intensification in CD and UC, even though loss of response is a problem in clinical practice common to both diseases. The primary objective of this study was to compare the need for and time to infliximab dose intensification in patients with CD and patients with UC in the same clinical setting. The drug administration costs were also compared between cohorts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and selection of patients

In this single centre, uncontrolled observational study, data collected prospectively as part of a well-established treatment protocol (see below) were retrospectively analyzed by chart review. All consecutive patients with CD or UC who started infliximab in the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Unit of our hospital between July 2008 and January 2010 were included. Only patients who responded to the three infliximab induction doses according to standard criteria and received at least the first infliximab maintenance dose were eligible. Infliximab was administered for CD or UC according to the indications accepted in the summary of product characteristics. The main reasons for prescription of infliximab were steroid-refractory disease and steroid dependence for both cohorts and perianal disease in the case of CD patients. The study was approved by the local hospital ethics committee.

Criteria for dose intensification

Patients were assessed for the need of infliximab dose intensification by two specialists in inflammatory bowel disease with more than 15 years of experience in this field. Prescription of infliximab in our unit follows a standard protocol that requires systematic recording in the database of demographic and disease characteristics prior to starting treatment, as well as information about therapy (doses administered and any adverse reactions). The demographic characteristics and disease characteristics of the patients on initiating treatment were extracted from this database. For the purposes of the analysis, the initiation of treatment was taken as baseline.

The need for dose intensification, whether by increased dose or decreased dosing interval, was noted. For patients who required dose intensification, the time relative to baseline (that is, the first induction dose) was recorded. For patients who did not require dose intensification, time on infliximab was calculated as the interval between the first infliximab induction dose and either the last follow-up visit or the time of infliximab discontinuation. Other treatment parameters such as concomitant corticosteroid or immunomodulatory therapy were also extracted. Adverse events were recorded throughout the infliximab treatment (both before and, if applicable, after intensification) in the clinical database.

Loss of response to infliximab was evaluated at each visit during maintenance therapy. In patients with luminal CD or UC the need for infliximab intensification was supported by measuring the Harvey-Bradshaw index[12] or the 9-point partial Mayo score[13], respectively. Loss of response was defined in those patients who responded to the infliximab induction doses but were not in remission as follows: Harvey-Bradshaw score ≥ 5 for luminal CD or 9-point partial Mayo score ≥ 4 for UC. Loss of response in fistulising CD was evaluated by assessing the number of draining fistulae, the amount of discharge and the presence of pain and the restriction of daily activities. Although these measures, together with the C-reactive protein (CRP) values, were used to guide the decision to intensify the dose, the final decision was made by the investigators taking into account the overall clinical situation of the patient. Before intensification in patients in whom an infection was suspected, other causes of persistent symptoms including coexistent cytomegalovirus or Clostridium difficile were ruled out.

Infliximab administration costs

The infiximab administration costs were calculated as the purchase price paid by the hospital together with the total number of infusions and the number of vials used per administration. The cost of the drug treatment was derived from the Catalogue of Pharmaceutical Specialties of the Spanish General Council of Pharmacists for the year 2010. The costs of the remaining resources, mainly day-care hospitalizations for infliximab administration, were obtained from the Spanish health-care costs database SOIKOS. The total administration costs (infliximab, pre-medication and day-care hospitalization costs) were calculated for each patient who were in treatment for at least 1 year. Results were weight-adjusted and expressed as cost (Euros) per kilogram for the first year of treatment.

Outcomes

The co-primary endpoints were the differences in the rates of patients requiring infliximab dose intensification per month and the intensification-free survival time between the cohorts of patients with CD or UC. We also evaluated the interval between the first infliximab induction dose and the first infliximab escalated dose. Potential predictors of the need for infliximab dose intensification such as age, gender, type of disease (CD or UC), disease duration, reason for infliximab prescription (steroid dependence, steroid-refractory disease, or perianal disease in the case of CD) and steroid or immunosuppressant use at baseline were investigated. We also calculated the impact of the type of disease and the need for dose intensification on infliximab administration costs.

Statistical analysis

Study variables were summarized descriptively using number and percentage for discrete variables and mean ± SD or medians (IQR) as appropriate for continuous variables. Demographic, disease and treatment characteristics were explored using the χ2 test for qualitative variables and the Student t-test and the median test if applicable for quantitative variables. The rates of intensification per patient-month of treatment were calculated. Intensification-free survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between curves evaluated using the Breslow exact test. A Cox proportional hazards survival regression analysis was employed to estimate the adjusted hazard ratios and their 95%CI. Variables with P < 0.10 in the univariate analysis were included in the model. The null hypothesis was rejected in each statistical test when P < 0.05. Analysis was performed using the SPSS version 15.0 (Chicago, IL, United States) statistical package for Microsoft Windows.

RESULTS

Ninety-seven patients from our prospectively maintained database of about 1400 patients with inflammatory bowel disease were evaluated. Demographic characteristics and the use of steroids or immunosuppressants at baseline (time of first infliximab induction dose) are shown in Table 1. The two cohorts showed no differences regarding sex, age and disease duration. At the time of diagnosis, more patients with CD were smokers, whereas more patients with UC were ex-smokers. Infliximab was indicated due to steroid-refractory disease in a higher proportion of UC patients. In one-third of CD patients (n = 19), infliximab was prescribed to treat complex perianal disease. Twenty-six patients (70%) had extensive UC, and 12 (30%) left-sided colitis. A greater proportion of UC patients were receiving steroids at baseline (P < 0.001). Infliximab was never administered as salvage therapy to hospitalized patients with severe UC refractory to intravenous steroids. There were no significant differences in the proportions of patients who were receiving immunomodulator treatment at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients enrolled n (%)

| Baseline characteristics | Ulcerative colitis | Crohn’s disease | P |

| (n = 38) | (n = 59) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Men | 16 (42.1) | 33 (55.9) | 0.184 |

| Women | 22 (57.9) | 26 (44.1) | |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 41.9 (14.2) | 38.9 (38.9) | 0.312 |

| Duration of disease [median (interquartile range), yr] | 4.5 (2-10.3) | 6 (1-12) | 0.738 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Non-smoker | 15 (39.5) | 21 (35.6) | 0.003 |

| Smoker | 8 (21.1) | 30 (50.8) | |

| Ex-smoker | 15 (39.5) | 8 (13.6) | |

| Steroid status | |||

| Neither steroid dependent nor refractory | 0 | 19 (32.2) | < 0.001 |

| Steroid dependent | 21 (55.3) | 33 (55.9) | |

| Steroid refractory | 17 (44.7) | 7 (11.9) | |

| Steroid use at induction | |||

| No | 10 (26.3) | 38 (64.4) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 28 (73.7) | 21 (35.6) | |

| Immunomodulator therapy | |||

| No | 7 (18.4) | 14 (23.7) | 0.536 |

| Yes | 31 (81.6) | 45 (76.3) |

Thirty-two patients required infliximab dose intensification, 16 of 38 (42%) patients with UC and 16 of 59 (27%) patients with CD. At the time of intensification, patients with luminal CD had a Harvey-Bradshaw score of 8.2 ± 4.6 (range 5-13) and the patients with UC a 9-point partial Mayo score of 5.9 ± 1.5 (range 4-8). Of these 32 patients with dose intensification, the dose was increased to 10 mg/kg every 8 wk in 10 patients and the dosing interval was shortened in the remaining 22 (to 5 mg/kg every 6 wk in 20 patients and to 5 mg/kg every 4 wk in two patients). There were no significant differences according to type of intensification between the two cohorts. At time of intensification, 18 out of 32 (56.3%) patients were on immunomodulators; the proportion was similar regardless of type of disease. Before the first intensified dose of infliximab, the mean ± SD CRP (mg/dL) was 1.8 (2.9) for patients with CD and 1.4 (3.2) for patients with UC.

Need for infliximab dose intensification

The duration of exposure to infliximab was longer in patients with CD than in patients with UC [median 13.1 mo (IQR: 8.1-23.3 mo) vs 9 mo (IQR: 5.2-12.5 mo), P = 0.006] (Table 2). Total exposure to infliximab was 404 mo for the 38 patients with UC compared to 1133 mo for the 59 patients with CD. The rates of patients requiring dose intensification per month with infliximab were significantly higher for UC compared with CD (3.9% vs 1.4% per month, P = 0.005). The rate of infliximab dose intensification per patient-month was not significantly different between perianal and luminal CD (1.2% vs 1.6% per month, P = 0.4). Patients with UC showed a significantly higher rate of infliximab dose intensification per patient-month when compared with the cohort of patients with luminal CD (3.9% vs 1.6% per month, P = 0.03). No significant differences in the rate of infliximab dose intensification per patient-month were observed for luminal CD according to Montreal localization (L1 vs L2+L3, P = 0.6).

Table 2.

Summary of dose intensification

| Dose intensification | Ulcerative colitis | Crohn’s disease | P value |

| (n = 38) | (n = 59) | ||

| Time on infliximab1 [median (interquartile range), mo] | 9 (5.2-12.5) | 13.1 (8.1-23.3) | 0.006 |

| Rate of intensification per patient-month | 3.9% | 1.4% | 0.005 |

| Time to infliximab intensification [median (interquartile range), mo] | 6.6 (4.2-9.5) | 10.7 (8.9-15.7) | 0.005 |

Time on infliximab: Interval of time between the first infliximab induction dose and the first infliximab intensified dose, or for patients who did not require dose intensification time between the initiation of infliximab and either the last follow-up visit or the time of infliximab discontinuation.

In patients who needed infliximab intensification, the median time from baseline to intensification was significantly shorter in the UC cohort compared to the CD cohort [6.6 mo (IQR: 4.2-9.5 mo) vs 10.7 mo (IQR: 8.9-11.7 mo), P = 0.005]. As shown in Figure 1, the Kaplan-Meier curves for cumulative probability of avoiding dose intensification rapidly separated for the two cohorts. The cumulative probability of avoiding infliximab dose intensification was higher in CD patients, with the Breslow exact test showing a highly significant difference (P = 0.002).

Figure 1.

Cumulative probability of avoiding infliximab dose intensification. The data below indicate the number and percent of patients at risk. Comparison using the Breslow test. CD: Crohn’s disease; UC: Ulcerative colitis.

Predictors of the need for infliximab dose intensification

The only factor significantly associated with the rates of patients requiring dose intensification per month was disease, with intensification being more likely with UC (HR = 2.73, 95%CI: 1.31-5.69, P = 0.007) (Table 3). Patients who were receiving immunomodulator treatment at baseline showed a trend toward a lower adjusted rate of infliximab intensification (HR = 0.51, 95%CI: 0.24-1.07, P = 0.08). Neither the need for steroids at baseline nor having steroid-refractory disease at baseline were associated with the need for infliximab dose intensification.

Table 3.

Summary of factors associated with dose intensification in the multivariate analysis

| Factor | Adjusted Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Corticosteroid dependence (yes/no) | 1.359 | 0.425-4.343 | 0.605 |

| Age | 1.015 | 0.991-1.040 | 0.216 |

| Induction with corticosteroids (yes/no) | 1.258 | 0.521-3.041 | 0.610 |

| 0Immunomodulator use (yes/no) | 0.510 | 0.242-1.073 | 0.076 |

| Disease (ulcerative colitis vs Crohn´s disease) | 2.732 | 1.313-5.686 | 0.007 |

Infliximab administration costs

The infiximab administration costs during the first year were significantly higher for UC patients compared to CD patients (mean ± SD 234.9 ± 53.3 Euros/kg vs 212.3 ± 15.1 Euros/kg, P = 0.03). The first-year infiximab administration costs to patients weighting 70 kg were 16443 Euros for UC and 14861 Euros for CD. In the multivariate analysis, only the type of disease (P = 0.02) and the need for infliximab dose intensification (P = 0.008) were associated with increased drug costs.

Safety

Twenty-five patients experienced a total of 42 adverse events during the whole follow-up period. Five adverse events were classified as severe: 2 herpes zoster, 1 severe delayed hypersensitivity reaction, 1 viral meningitis and 1 leishmaniosis. Six adverse events led to the discontinuation of infliximab: 1 herpes zoster, 1 severe delayed hypersensitivity reaction, 1 viral meningitis and 3 acute infusion reactions. Two of the severe adverse events that led to discontinuation occurred in patients with intensified doses.

DISCUSSION

This study compares for the first time the need for infliximab dose intensification between patients with UC and CD in the same clinical setting. Our study also provides an updated comparison of the drug administration costs between cohorts, which is necessary in understanding the economic burden of inflammatory bowel disease. Infliximab is a chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody with a high affinity for TNF-α, which is an important cytokine in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease[14]. The validity of using TNF-α as a therapeutic target has been demonstrated in randomized clinical trials with infliximab in both the induction and maintenance setting of luminal[2] and fistulising CD[3] and in UC[5].

Despite the proven efficacy of infliximab in the maintenance setting, loss of response is a real problem. Gisbert et al[11] reviewed 16 studies that assessed loss of response in CD. For follow-up durations of between 5 and 72 mo, the loss of response ranged from 11% to 54%. The authors calculated that the annual risk of loss of infliximab response was 13.1%, which is similar to the rate found in our study (1.4% per patient-month or 16.8% annually of patients who lost response and required dose intensification). Gisbert et al[11] also studied the outcomes of infliximab dose intensification and found evidence of the effectiveness of the approach. For example, in the ACCENT 1 study, dose intensification to 10 mg/kg was effective in 90% of the patients in the 5 mg/kg dose arm who had loss response[4]. In a multicentre study, dose intensification, whether by doubling the infliximab dose or by shortening the dosing interval to 5 mg/kg every 4 wk, enabled response to be regained in 73% of patients[15].

In the case of UC, the need for infliximab dose intensification is less well defined. The extension study of the pivotal ACT trial reported that only 7% of patients required dose intensification[6]. The situation in clinical practice, however, would seem to be very different. In observational studies, the proportion of patients who needed infliximab dose intensification ranged between 42% and 58% for follow-ups between 14 and 18 mo (Table 4)[7-10]. The need for intensification in our study (42% after a median of 9 mo of follow-up) is within the range reported in the other studies performed in a clinical practice setting[7-10].

Table 4.

Summary of studies of infliximab dose intensification in ulcerative colitis: Proportion of patients who needed infliximab intensification

| Ref. | Patients1 | Median duration of follow-up (mo) | Dose intensification |

| Rostholder et al[7] | 50 | 142 | 54% |

| Oussalah et al[8] | 80 | 18 | 45% |

| Seow et al[9] | 93 | 14 | 58% |

| Arias et al[10] | 136 | 14 | 46% |

| Present study | 38 | 9 | 42% |

Only patients who responded and started maintenance therapy;

Mean duration.

To the best of our knowledge there are no studies published comparing the need for infliximab dose intensification for UC and CD in the same hospital or by the same specialists. Given that the rationale for dose intensification in UC is not supported by randomized studies, such a comparison provides further support for this therapeutic approach. There is also a need for long term observational data on the costs incurred by patients selected for anti-TNF-α therapy, without forgetting that the intensification of the drug is one of the main drivers of the increased direct costs[16]. Our study confirmed that the drug intensification rates had a significant impact on infiximab administration costs. The infiximab administration costs were higher in patients with UC, and this was related to the increased need for drug intensification in this cohort of patients.

We observe a higher rate of dose intensification per patient-month in patients with UC, and this dose intensification is also required earlier than in patients with CD. Although it could be argued that the size of the cohort and follow-up are limited, we have compared more than 400 and 1100 mo of follow-up for patients with UC and CD, respectively, resulting in highly significant differences in the primary endpoints. In addition the differences were established very early in time, and do not seem reasonable that it would change with longer follow-ups. Loss of response to infliximab and other anti-TNF-α agents in CD is generally thought to arise because of the immunogenic nature of these drugs. For example, in a paediatric study, 22% of responders at the end of follow-up had developed anti-infliximab antibodies compared to 75% of children who had lost response[17]. In patients with UC, repeated administration may lead to the development of anti-infliximab antibodies over time, inducing a drop in infliximab trough serum levels and hence the need for dose intensification[9]. Arias et al[10] showed that patients with UC who displayed low infliximab trough levels demonstrated shorter time to dose intensification. However, in our study, the Kaplan-Meier curve of time to intensification (Figure 1) clearly shows that a proportion of patients with UC require dose intensification earlier in follow-up than is the case for Crohn’s patients. This is a reflection that more patients with UC need infliximab dose intensification at the start of the maintenance period. It may be that UC, which is a different disease entity, may require higher doses of infliximab for an initial control of the disease. Seow et al[9] described a high proportion of patients with UC with absent trough levels of infliximab that contrast with other studies in CD. They suggested that the explanation could be a more rapid clearance of infliximab in UC patients.

Several reasons might explain the reported high rates of infliximab dose intensification in patients with UC. First, such an approach in CD patients has been shown to be effective, while administration every 8 wk of the 10 mg/kg has been shown to have an equivalent safety profile compared to the lower dose, both in CD[2-4] and UC[6]. Second, in a subset of patients with UC, infliximab could be used as a last resort to avoid the need for colectomy. In a subanalysis of pooled data from the ACT1 and ACT2 trials, there was a significant difference between the 10 mg/kg dose group and placebo in terms of reduced need for colectomy but not for the 5 mg/kg dose group[18]. Third, when the study was performed, infliximab was the only anti-TNF agent approved for use in UC. In clinical practice, adalimumab has only been used as an alternative treatment in UC after discontinuation of infliximab due to an adverse effect or after loss of response despite intensification[19]. Cyclosporine is also useful when used as rescue therapy in acute severe steroid-refractory UC, but patients need to be hospitalized[20,21]. Interestingly, a recent survey of clinical practice showed that not only adult gastroenterologist but also paediatric gastroenterologist who prescribed infliximab considered that intensified doses of infliximab have a recognized role and perceived benefit in the treatment of some paediatric UC patients[22].

The study is subject to a number of limitations. First, this was a retrospective study. However, the data were collected prospectively by the same two inflammatory bowel disease specialists according to the infliximab treatment protocol. Another limitation of the study was the discretional criteria used to decide infliximab dose intensification. In the ACCENT 1 study the loss of response was defined by an increase in CDAI for patients with CD[4]. In the ULTRA 1 study the need for adalimumab dose intensification in patients with UC was defined according to the Partial Mayo Score values[23]. Therefore in clinical trials the definition of loss of response or inadequate response during the maintenance phase has been based on clinical activity indexes, and not on c-reactive protein values nor on endoscopic assessment. In our study, the physician global assessment, supported by the Harvey-Bradshaw score or the Partial Mayo Score, was used to guide the decision to intensify the infliximab dose. This assessment is subject to potential bias. CRP values were also taken into account in the final decision. In conclusion, in contrast to the case in clinical trials, the decision to escalate the dose of infliximab is based on “real life” clinical practice.

Another weakness of the study is that, in our clinical practice, infliximab trough serum levels and anti-infliximab antibodies titres are not usually determined. Such information could be useful for explaining the differences in the need for infliximab dose intensification between the two diseases, and also to understand the possible role of combination therapy in the reduction of anti-infliximab immunogenicity[24]. Genetic test were not available in our study. Genetic polymorphisms may contribute to predict efficacy of infliximab[25,26].

As regards the adverse effects profile, our results are similar to those of large controlled series in patients with CD or UC treated with infliximab[2,3,6].

In conclusion, in clinical practice, the rate of patient-months of treatment with need for infliximab dose intensification was higher in patients with UC compared to patients with CD. Patients with UC required intensification of infliximab dosing earlier and infliximab intensification-free survival was also lower in these patients. The infiximab administration costs were higher in patients with UC. Our data provide a rational basis for economic planning in patients with inflammatory bowel disease selected for anti-TNF-α therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Cristina Fernandez for her assistance in the statistical analysis and Dr. Gregory Morley for writing support and for reviewing the English manuscript.

COMMENTS

Background

Despite the proven efficacy of infliximab in the maintenance setting, loss of response is a real problem. Infliximab dose intensification to counteract loss of response is well established in the management of patients with CD. In UC, the need for infliximab dose intensification is less well established.

Research frontiers

The results provide a rational basis for economic planning in patients with inflammatory bowel disease selected for anti-TNF-α therapy.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The study compares for the first time the need for infliximab dose intensification for UC and CD in the same clinical setting.

Applications

The study also provides an updated comparison of the drug administration costs between cohorts, which is necessary in understanding the economic burden of inflammatory bowel disease. The infiximab administration costs were higher in patients with UC.

Terminology

Infliximab dose intensification: need for infliximab dose intensification, whether by increased dose or decreased dosing interval.

Peer review

The investigation has profound therapeutically implication highlighting the problem of intensification of infliximab in the phenotypes of inflammatory bowel disease, CD and UC, incorporating the administration costs as well.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Coffey JC, Efthymiou A, Gara N, Marina IG, Maric I S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G, Vermeire S. Review article: Infliximab therapy for inflammatory bowel disease--seven years on. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:451–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W, et al. Comparison of scheduled and episodic treatment strategies of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:402–413. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, de Villiers WJ, Blank M, Lang Y, et al. Long-term infliximab maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis: the ACT-1 and -2 extension studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:201–211. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rostholder E, Ahmed A, Cheifetz AS, Moss AC. Outcomes after escalation of infliximab therapy in ambulatory patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:562–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oussalah A, Evesque L, Laharie D, Roblin X, Boschetti G, Nancey S, Filippi J, Flourié B, Hebuterne X, Bigard MA, et al. A multicenter experience with infliximab for ulcerative colitis: outcomes and predictors of response, optimization, colectomy, and hospitalization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2617–2625. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seow CH, Newman A, Irwin SP, Steinhart AH, Silverberg MS, Greenberg GR. Trough serum infliximab: a predictive factor of clinical outcome for infliximab treatment in acute ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2010;59:49–54. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.183095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arias MT, Van de Casteele N, Drobne D, Ferrante M, Cleynen I, Ballet V, Rutgeerts P, Gils A, Vermeire S. Importance of trough serum levels and antibodies on long-term efficacy of infliximab therapy in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2012;6(Suppl 1):S5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisbert JP, Panés J. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:760–767. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Sandborn WJ, Dubois C, Rutgeerts P. Correlation between the Crohn’s disease activity and Harvey-Bradshaw indices in assessing Crohn’s disease severity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis JD, Chuai S, Nessel L, Lichtenstein GR, Aberra FN, Ellenberg JH. Use of the noninvasive components of the Mayo score to assess clinical response in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1660–1666. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Dullemen HM, van Deventer SJ, Hommes DW, Bijl HA, Jansen J, Tytgat GN, Woody J. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with anti-tumor necrosis factor chimeric monoclonal antibody (cA2) Gastroenterology. 1995;109:129–135. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz L, Gisbert JP, Manoogian B, Lin K, Steenholdt C, Mantzaris GJ, Atreja A, Ron Y, Swaminath A, Shah S, et al. Doubling the infliximab dose versus halving the infusion intervals in Crohn’s disease patients with loss of response. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2026–2033. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bodger K. Cost effectiveness of treatments for inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29:387–401. doi: 10.2165/11584820-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Candon S, Mosca A, Ruemmele F, Goulet O, Chatenoud L, Cézard JP. Clinical and biological consequences of immunization to infliximab in pediatric Crohn’s disease. Clin Immunol. 2006;118:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Lu J, Horgan K, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, et al. Colectomy rate comparison after treatment of ulcerative colitis with placebo or infliximab. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1250–1260; quiz 1520. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taxonera C, Estellés J, Fernández-Blanco I, Merino O, Marín-Jiménez I, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Saro C, García-Sánchez V, Gento E, Bastida G, et al. Adalimumab induction and maintenance therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis previously treated with infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:340–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, Allez M, Bouhnik Y, Filippi J, Zerbib F, Savoye G, Nachury M, Moreau J, et al. Ciclosporin versus infliximab in patients with severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1909–1915. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang KH, Burke JP, Coffey JC. Infliximab versus cyclosporine as rescue therapy in acute severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:287–293. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1602-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nattiv R, Wojcicki JM, Garnett EA, Gupta N, Heyman MB. High-dose infliximab for treatment of pediatric ulcerative colitis: a survey of clinical practice. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1229–1234. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i11.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, D’Haens G, Wolf DC, Kron M, Tighe MB, Lazar A, Thakkar RB. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:257–265.e1-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bortlik M, Duricova D, Malickova K, Machkova N, Bouzkova E, Hrdlicka L, Komarek A, Lukas M. Infliximab trough levels may predict sustained response to infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steenholdt C, Enevold C, Ainsworth MA, Brynskov J, Thomsen OØ, Bendtzen K. Genetic polymorphisms of tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1b and fas ligand are associated with clinical efficacy and/or acute severe infusion reactions to infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:650–659. doi: 10.1111/apt.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medrano LM, Taxonera C, Márquez A, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Gómez-García M, González-Artacho C, Pérez-Calle JL, Bermejo F, Lopez-Sanromán A, Martín Arranz MD, et al. Role of TNFRSF1B polymorphisms in the response of Crohn’s disease patients to infliximab. Hum Immunol. 2014;75:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]