Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this article is to explore treatment needs and factors contributing to engagement in substance use and sobriety among women with co-occurring substance use and major depressive disorders as they return to the community from prison.

Design

This article used qualitative methods to evaluate the perspectives of 15 women with co-occurring substance use and major depressive disorders on the circumstances surrounding their relapse and recovery episodes following release from a U.S. prison. Women were recruited in prison; qualitative data were collected using semi-structured interviews conducted after prison release and were analyzed using grounded theory analysis. Survey data from 39 participants supplemented qualitative findings.

Findings

Results indicated that relationship, emotion, and mental health factors influenced women’s first post-prison substance use. Women attributed episodes of recovery to sober and social support, treatment, and building on recovery work done in prison. However, they described a need for comprehensive pre-release planning and post-release treatment that would address mental health, family, and housing/employment and more actively assist them in overcoming barriers to care.

Practical implications

In-prison and aftercare treatment should help depressed, substance using women prisoners reduce or manage negative affect, improve relationships, and obtain active and comprehensive transitional support.

Originality/value

Women with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders are a high-risk population for negative post-release outcomes, but limited information exists regarding the processes by which they relapse or retain recovery after release from prison. Findings inform treatment and aftercare development efforts.

Keywords: Prison, women, substance use disorder, major depressive disorder, treatment

1. Introduction

The United States incarcerates more individuals both in absolute terms and per capita than does any other country in the world (Walmsley, 2009). Drug crimes and other non-violent crimes such as property crimes account for 64% of the U.S. female state prison population (Guerino et al., 2011). As a result, women tend to serve short sentences (less than a year) and quickly return to the community (Bonczar, 2011). Understanding the processes by which women relapse to substances or maintain sobriety as they re-enter the community from prison is critical to designing successful aftercare strategies to prevent substance relapse and reincarceration.

Although the criminal justice system and its treatments have historically been designed for men, the increasing number of incarcerated women, especially substance-involved women, has brought more attention to their needs. Research on samples entering prison addiction treatment has found that, prior to prison, women used drugs more frequently, used harder drugs, and used them for different reasons than do men (pain alleviation vs. euphoria; Langan & Pelissier, 2001; Messina et al., 2003). Substance-involved female offenders are also more likely than male offenders to have a spouse or close friend with a drug problem (Langan & Pelissier, 2001; Messina et al., 2003, 2006; Pelissier et al., 2003). Other issues that complicate re-entry, such as low levels of education, poor vocational skills, co-occurring mental health problems, suicidality, physical or sexual abuse, and poor physical health, and childcare responsibilities are more common among substance-involved incarcerated women than among substance-involved incarcerated men (Adams et al., 2008; Greenfield et al., 2007; Langan & Pelissier, 2001; Messina et al., 2003, 2006; Pelissier et al., 2003; Zlotnick et al., 2008). These risks are in addition to those posed to all re-entering populations, including difficulties finding housing and employment, resurgence of high-risk behavior (Pelissier et al., 2007), and overdose (Binswanger et al., 2011; Moller et al., 2010).

Co-occurring mental health disorders are especially common among substance-using incarcerated women (Melnick et al., 2008). For example, 32–38% of women in prison substance use treatment meet lifetime criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD; Pelissier & O’Neil, 2000; Zlotnick et al., 2008). Co-occurring MDD may increase risk of relapse to substances and other adverse outcomes as women re-enter the community. For example, in community samples, depression has been associated with poorer prognosis after substance use treatment (Bottlender and Soyka, 2005; Brown et al., 1997; Brown et al., 1998; Kosten et al., 1986; McKay et al., 2002; Richardson et al., 2008; Rounsaville et al., 1986), and situations involving negative mood are among the most frequently cited precipitants of relapse across several substances (Hodgins et al., 1995; Shiffman et al., 1996; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004), especially for women (Zywiak et al.., 2006). In prisons, co-occurring psychiatric conditions, including MDD, have been associated with nearly three times the rate of dropout from substance use treatment programs (Brady et al., 2004). Depression predicts prison recidivism in women (Benda, 2005). Furthermore, the impairment in social (Hammen, 1991) and occupational (Broadhead et al., 1990) functioning seen with MDD can have serious consequences for a woman leaving prison, interfering with her ability to establish a stable life in the community. Although previous studies have identified women with co-occurring disorders as a high-risk population for substance use relapse, limited information exists regarding the processes by which they relapse or retain recovery after release from prison. Although some literature has addressed the effectiveness of psychopharmacologic and behavioral interventions for substance use among men or among returning prisoners in general (e.g., Kinlock et al., 2009; Sacks et al., 2012; Springer et al., 2012), little literature exists to guide the development of prison aftercare programs for substance-using women, especially those with co-occurring mental health conditions (Pelissier et al., 2007).

What limited research that does exist is primarily quantitative in nature (Pelissier et al., 2007). Although quantitative analysis is essential, with a poorly understood and high-risk population, it is possible that researchers would make erroneous assumptions of what is needed in terms of aftercare, potentially limiting our ability to intervene successfully to the unique needs of incarcerated women. Use of qualitative data allows participants to speak for themselves without overlaying researcher assumptions, and may be useful in developing treatments that are tailored to substance users’ specific needs and desires (Neale et al., 2005; Samson et al., 2001; Richardson et al., 2000). Moreover, use of such qualitative methods may permit a more in depth and honest understanding of the nature of relapse and barriers to treatment given that rapport is required to gather sensitive information from formerly incarcerated substance abusers (Neale et al., 2005). This study used individual semi-structured qualitative interviews to inform the understanding of the transitional treatment needs of incarcerated women with co-occurring disorders (MDD and substance use disorder) and the processes by which they re-initiate substance use or maintain sobriety as they re-enter the community.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants for the current study were taken from two trials of treatments for co-occurring substance use and MDD among incarcerated women nearing release to the community. Inclusion criteria for these trials were: (1) current primary (non substance-induced) MDD as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al., 1996) after at least 4 weeks of abstinence and prison substance use treatment, with a minimum 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale (HRSD; Hamilton, 1980) score of 18, indicating moderate to severe depression; (2) substance use disorder (abuse or dependence on alcohol or drugs) one month prior to incarceration as determined by the SCID; (3) 10–24 weeks away from prison release. Women who met SCID lifetime criteria for bipolar disorder or psychotic disorder were excluded. All participants could speak English. The first trial (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2012; registered at clinicaltrials.gov under number NCT00606996) compared an adapted version of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) to attention-matched psychoeducation on co-occurring disorders. The second (Johnson, Williams, & Zlotnick, under review) pilot tested an adaptation of IPT focused on improving network support for sobriety, and included post-release phone contact between prison counselors and re-entered women. Primary outcomes for both trials were post-prison substance use and depressive symptoms.

Prison substance use treatment as usual used cognitive-behavioral and 12-step approaches, and consisted primarily of large group drug education, with weekly individual sessions with bachelor’s level substance abuse counselors. At re-entry, women leaving prison are typically referred for substance abuse treatment in the community (residential or outpatient counseling and/or twelve-step self-help groups) and given two weeks of psychiatric medications; use of pharmacotherapy (e.g., methadone) to prevent post-release substance use is rare. Both trials added psychosocial treatment for MDD (either interpersonal psychotherapy or psychoeducation on co-occurring disorders groups that met 3 hours per week for 8 weeks) to prison day (18 hours per week) or residential (30 hours per week) substance abuse treatment as usual. The rationale was that additional targeted focus on reducing depression in the weeks leading up to re-entry might allow re-entering women to better cope with the stresses of re-entry. The first trial included 38 sentenced female prisoners from a northeastern U.S. state and took place between 2006 and 2009 (Johnson & Zlotnick, 2012). However, in following women as they returned to the community, we noticed that many women who relapsed to substances did so in the first few days after release, meaning that relapse often occurred before and possibly prevented women’s connection to post-release outpatient substance use and mental health treatment. Furthermore, many women experienced serious problems (e.g., unsafe living conditions, violence) within days of being released and before they were able to engage in post-release care. We were concerned that many women who had made good therapeutic strides in prison were doing so poorly so soon after prison release.

To better understand the processes by which women with co-occurring MDD and substance use were re-initiating substance use in the first days and weeks after community re-entry and to inform transitional intervention development efforts, we collected additional information in “epilogue interviews.” In 2009 and 2010, we were able to re-locate, re-consent, and interview 20 women (12 in the community and 8 who had been re-incarcerated) a mean of 13 (range 3 – 27) months after their index release from prison. The epilogue interviews (Table 1) included a structured verbal interview guide and a verbally administered survey about women’s post-release substance use and sobriety. Post hoc qualitative analysis used 15 of the 20 women from the first trial who provided audio recorded epilogue interviews (5 additional interviews were not recorded due to participants not consenting to recording, faulty recorders, or prison staff refusing to let recorders into their facilities).

Table 1.

Interview guide

| Relapse |

|---|

|

| Recovery |

|

| Desired Treatment Factors |

|

| Non-Qualitative Survey Questions |

For first post-prison drug use or heavy drinking, ask:

|

For periods of sobriety/recovery, ask:

|

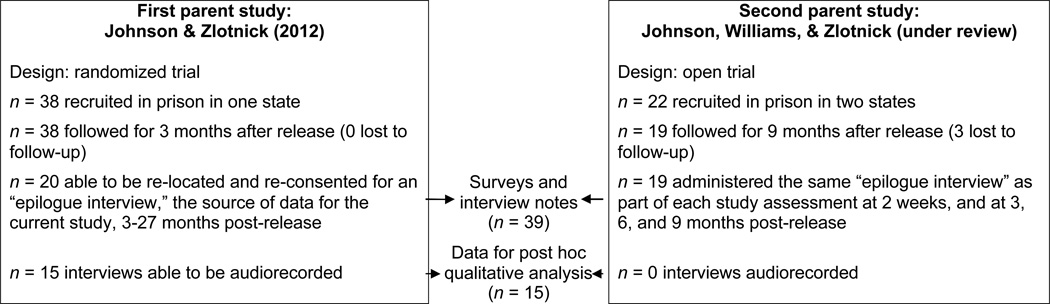

The second trial (Johnson, Williams, & Zlotnick, under review) included an additional 22 sentenced female prisoners from two northeastern states and took place from 2009 to 2011. We were able to conduct the same verbal epilogue interviews and surveys with 19 of these women as we had in the first trial. Because our original purpose was to understand what happened as women were released rather than to conduct qualitative research, we took careful written notes recording each participant’s response to each question, but did not audiotape epilogue interviews from the second trial. Because written notes provide less detail than do transcripts, interviews from the second trial have not been included in qualitative analysis. However, survey data and research staff interview notes from all 39 women (20 from the first trial and 19 from the second) were used to supplement findings from the first trial (see Figure 1), and are reported in Section 3.2. Because the epilogue was administered at several time points in the second trial (2 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months after release from prison), we used data about first substance use post prison release from the first interview where use was reported, and information about periods of sobriety from the last interview where such periods were reported.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants into current study

2.2. Procedures

Potential participants were recruited for the two original studies through announcements made in prison substance abuse programs. Based on those announcements, women privately volunteered for the initial assessment. Study staff conducted informed consent procedures in private rooms. There were no legal incentives and minimal financial incentives (US$30) for participation. Interviews for this study took place either as part of regularly scheduled assessments (for participants in the second trial) or following reconsent procedures (for participants in the first trial). The study followed ethical guidelines for research with prisoners under institutional and prison ethics review board approvals.

Epilogue interviews, including the structured verbal interview guide and a verbally administered survey about women’s post-release substance use and sobriety (Table 1), were conducted verbally and individually by the first author or a research assistant. A semi-structured interview protocol gathered data in three areas (Table 1). First, for participants who reported drug use or heavy drinking (4 or more drinks on one occasion) since their release from prison, questions were asked about the circumstances surrounding this first episode of use. Second, participants who reported periods of sobriety since release from prison were asked about factors contributing to this sobriety. Finally, all participants were asked what features of treatment were desirable for women with co-occurring substance use and MDD nearing prison release. Verbal survey questions assessed mood and interpersonal circumstances surrounding post-release use, as well as supports for recovery.

Timeline Followback Interview (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) data from the parent studies was used to quantify the timing of first post-prison use, and was cross-walked against the urine drug screens (which measured marijuana, cocaine, stimulant, opioid, and benzodiazepine use) conducted at 2 weeks and 3 months post-release in the parent studies.

2.3. Qualitative analysis

The 15 interviews that were audiotaped were transcribed and anonymized before coding. Open coding strategies (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) were used to generate a preliminary codebook which was iteratively refined as additional transcripts were coded. Data saturation (i.e., no new codes emerging as additional transcripts were identified) was verified before the final step of selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Finally, using the codebook generated from the initial open coding (which results in emergence and naming of categories) and axial coding (where codes developed through open coding are related to one another) steps, all transcripts were submitted to a final selective coding process in which the codebook was validated against the data and data saturation was re-verified.

A team of trained coders (3 to 5 for each transcript) analyzed and coded each transcribed interview allowing themes from each of the three areas of inquiry (relapse triggers, recovery facilitators, desired treatment factors) to emerge. Each coder independently reviewed, selected, and coded qualitative responses, which were entered into NVivo analysis software. Quotations that most accurately reflected an emerging concept (e.g., exposure to known relapse triggers) were chosen from among text that had been marked. During bi-weekly meetings, transcripts were discussed line-by-line, and coding among the coders was reconciled to represent team consensus about the meaning of utterances. Coding was initially conducted on the specific concept level (e.g., lack of housing), and codes were subsequently clustered into broader unified themes (e.g., housing and jobs). Coders independently conducted selective coding and discussed as the codebook was finalized and a closing team consensus meeting was used to conduct a final verification of the codebook.

3. Results

Characteristics of both the survey sample and the subset that provided qualitative interviews are shown in Table 2. The goal of qualitative data analysis (n = 15; Section 3.1) was to describe the context and precipitants of relapse and recovery and desired treatment factors for women prisoners with co-occurring substance use disorders and MDD as they returned to the community. Survey data (n = 39; Section 3.2) supplemented qualitative findings with quantitative and short answer responses. All participants endorsed the perspective that re-entry into the community is a challenging transition period with a heightened risk for relapse.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics

| Written survey sample (n = 39) | Subset with recorded qualitative interviews (n = 15) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 36 (9.8) | 36 (9.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African-American | 8 (20%) | 3 (20%) |

| Hispanic | 4 (10%) | 1 (7%) |

| Intake SCID-I substance use diagnosisa – n (percent) |

||

| Alcohol dependence | 26 (67%) | 11 (73%) |

| Cocaine dependence | 19 (49%) | 8 (53%) |

| Opioid dependence | 16 (41%) | 3 (20%)* |

| Sedative/hypnotic/anxiolytic dependence |

9 (23%) | 1(7%) |

| Median substance use patterns in 180 days prior to prison |

||

| Drug using days (SD) | 100 (65) | 67 (61) |

| Heavy drinking (5+ drinks) Days (SD) |

27 (55) | 66 (60) |

| Days abstinent from alcohol and drugs (SD) |

47 (51) | 71 (46) |

| Median sentence length in months (SD) |

11 (8) | 12 (13) |

| Community treatment received in first 3 months after prison release |

||

| Any residential treatment | 42% | 47% |

| Any substance use or mental health counseling |

77% | 79% |

| Any twelve-step self-help meetings |

89% | 100% |

| Any psychiatric medications | 63% | 57% |

| Any medications for substance abuse |

3% | 7% |

Percents add up to more than 100% because many participants had multiple substance dependence diagnoses

Participants in the qualitative subsample differed significantly from the remaining 24 participants for whom interviews were not recorded.

3.1. Qualitative Findings (n = 15)

3.1.1. Relapse triggers

Theme 1: Difficulty in romantic relationships

Many women described how romantic relationships contributed to risk for first post-release substance use. As one participant described: “I [found] out he was with his ex-girlfriend the night before. This is the cause of a lot of my problems. The drinking is because he always blows me off, so I started drinkin’.” In particular, having a partner who they discover is cheating on them, or a partner who sells and/or uses substances was also described to contribute to substance relapse. As one participant noted: “The person I was with sold. That's why.” More general relationship conflict, rejection, or perceived abandonment was also described as being a factor contributing to substance relapse. For example, one participant explained that, “Yeah, being hurt, abandoned. That’s what triggers [substance use].”

Theme 2: Uncomfortable emotions

ranging from hurt and loneliness to boredom, and the challenge of experiencing such emotions, were described as a major contributing factor to women’s first post-prison use of substances. For example, one woman noted that substance use was actively used as a coping mechanism for insecure feelings: “That’s my coping skill is to drink and drug when I’m feelin’ insecure about myself.” Another participant described a situation where feeling angry with a family member triggered her to drink: “That time I drank after. It was Saint Patrick’s Day, and I was really mad about my mother.” Other women described that the experience of feeling bored or lonely and not knowing what else to do often leads to picking up substances.

Theme 3: Mental health problems

In addition to general emotional factors, several women also described psychiatric problems playing a central role in their first post-release substance use. As all women in the study were diagnosed with MDD, the focus on mental health was often on depression (e.g., “I didn’t wanna’ feel depressed anymore and I know that if I drink I won’t feel anything.”). However, other psychiatric conditions also mentioned included anxiety, anger, mood swings, and having “nervous breakdowns”. Not having access to treatment, using medications inappropriately, or terminating medication use entirely was also described as a factor leading to relapse: “I picked up alcohol but I think it mighta’ had something to do with because there’d been a lapse of me not being on my meds for a coupla’, like maybe two weeks.”

Theme 4: Substance illness

Exposure to people, places, and things that are commonly known to trigger substance relapse was described as being central to first post-release substance use among participants. Participants even described that, at times, the exposure was entirely unexpected and undesired, but difficult to escape: “I ran into somebody… He stopped and said,’ Oh, you need a ride?’ And I said, ‘yeah, sure…’ And that was it. I really didn’t expect them to have that [drugs], either. It was a surprise.” Participants also described a common coping style of using substances. One participant noted: “It just helped me cope with my situation.” Alcohol as a gateway to other substance use was also described: “I just went to the liquor store. I went to the liquor store and picked up the alcohol. That’s what I usually do because then I can tell myself you know, that it wasn’t me that made the decision. It was because I had the alcohol in me, I picked up the drugs. That’s what I do.” Several participants also described the potent role of cravings and urges to use. For example, one woman described: “I just wanted the euphoric part of it, the high part of it, the numb part of it.” Some participants described trying to resist urges to use, but ultimately not being successful (particularly when the substance was in close proximity): “I mean, at first, I was like, ‘no no no no’. Then he did it, and I smelled it, I just had to have it. I couldn’t—I said oh, the hell with it, gimme some.” Participants also described wanting to believe that they could use in a more controlled way, but that limited use would often lead them back into more heavy and ongoing substance abuse: ‘It wasn’t meant to be like continual. I think I picked up saying, ya’ know, I could do it once… Then before I knew it, I was probably lying to myself because I know if I pick up, most of the time it’s stumble and fall.”

Theme 5: Lack of housing and employment

Participants described lack of stable housing, difficulty securing employment, and not having identification to permit them to obtain these basic necessities as relapse triggers. As one participant noted, “First, I’m homeless. I had no place to go. I had no job. So I just was drinking.” Several participants noted that upon discharge, they expected that the logistical aspects of their lives would fall into place quickly. When it became apparent that obtaining housing and a job would take more time, frustration and impatience would set in and, for some, triggered a relapse: “I tried to get work. I think that might’ve been one of the other things, you know, like everything wasn’t comin’ together.”

3.1.2. Recovery Facilitators

Theme 1: Support

The majority (13 of 15) of participants described aspects of social or sober support as integral to substance recovery. Sources of support described varied widely. Some participants noted that an important place where sober support could be sought was through treatment, either through attendance in a group treatment program with women who were a positive influence or through having a sponsor or mentor who could provide guidance and be called on during difficult times. Some people described family, including children, significant others, and parents, as being their central sober support. As one participant summed up, “You need a good network support system, you really do.” A number of women emphasized the importance of same-sex support, rather than romantic support, and discussed the role that toxic romantic relationships can play in substance use. For example, one participant noted that “…anyone in recovery needs a support system, preferably a female-dominated support system.” Several women also noted that a support system needed to be characterized by lack of judgment to permit them to open up more easily. In one participant’s words, she described that the most important thing was “… talking and people listening and people who have been there. Even some people who haven’t been there, but just people that—I think people that support you and people that pretty much are—will support you and will back you up and don’t judge you. I think that’s the hardest thing is finding somebody who doesn’t judge you.”

Theme 2: Avoiding known relapse triggers

A common Alcoholics Anonymous aphorism reflects the importance of avoiding people, places, and things that are known triggers for substance use. Many of the participants endorsed this strategy as one that promoted their sobriety. As one participant stated: You have to “get a network and stay away from the people, the surroundings that you were in. You gotta get away from what you were at. Like people, places and things.” Some participants spoke specifically about toxic romantic relationships as a trigger for relapse, and how avoidance of these relationships was of great importance. Some participants highlighted the utility of providing women re-entering the community with a controlled environment where triggers could be minimized, but described a preference that such an environment would “not [be] a lock-in thing.”

Theme 3: Clean time from prison or fear of future legal sanction

Several participants noted that accruing clean time during incarceration and/or fear of additional legal problems motivated them to stay sober. One participant stated: “I think being able to have some clean time helped.” With respect to the threat of additional jail time, one participant stated: “That’s gonna be much of the answer that I’m gonna give you is I didn’t want to go back to jail.”

Theme 4: Treatment

Participants described considerable benefit from treatment in promoting their recovery. Twelve-step programs were described as common, and useful when used at sufficient levels. As one participant described: “If you have a problem, go to an AA or NA meeting. They do help. They really do. I found out when I’m there, I feel better.” However, other mental and substance treatment was also described as being important, especially treatment that addressed their own unique mental health, interpersonal, or psychopharmacologic needs. Others mentioned learning relaxation skills, having a program focused on spirituality, and learning about the connection between mental health and substance use as helpful.

Theme 5: Motivation and confidence to make changes in substance use

Participants discussed the contribution of motivation and confidence to make and maintain lifestyle changes to recovery. One participant described her willingness to do “whatever it takes” because she was “…tired of coming [to jail]”. Other women described other motivating factors, including family, and specifically their children. As one woman stated, she was motivated to maintain sobriety for “…freedom. My son…. And plus just-I don’t know. I don’t wanna be a crackhead at 42 years old.” Confidence as a central ingredient to making changes was also highlighted: “I was confident… That’s it.”

Theme 6: Increased self-awareness and self-care

Participants noted that insight and taking good care of themselves, which they sometimes learned for the first time in prison, facilitated their recoveries. For example, insight into the connection between depression and substance use was described as contributing to recovery: “I think part of what helped me was I never recognized before that I had, the seriousness of my depression, and that it had an effect on whether I used a lot.” Other participants described the benefit of gaining insight into feelings, personal issues, and strengths. One participant also described that self-care was important in staying sober: “… Now I just put a little bit more effort into making myself feel better.”

Theme 7: Housing and employment

On a more practical level, women described the importance of having a safe place to go at prison release as promoting recovery. Having a job was also highlighted as being helpful because it kept women busy and distracted from alternative substance use activities. As one participant noted, “just pretty much staying busy and not having time for anybody” helped her to stay sober.

3.1.3. Recovery barriers

Theme 1: Barriers to accessing support

Participants described how difficult it was to access social support, both because they did not wish to access supports or because supports which they wished to access were unavailable. One participant attributed her isolation to having burned out support sources. She described, “I used to [call him] really bad, but he’s tired of hearing it.” Other participants described that reaching out to supports “didn’t help” to make them feel better. Still others reported a preference to deal with things on their own: “I don’t like to talk about things a lot. I just think I can take care of myself.” As a consequence of not having available supports, participants noted that engaging in self-help activities was challenging. One participant described the difficulty in attending twelve-step meetings alone: “I won’t go by myself. I know people that go on a Thursday night meeting I do go to, but I don’t like walking in alone.”

Theme 2: Challenges with treatment

Although several treatment factors were identified as facilitative of recovery, participants also described elements of treatment that were problematic. Several participants noted that some community treatment programs were overly punishing and judgmental, reducing their positive motivation to stay sober. One participant gave this suggestion: “Allow people to make mistakes. People are going to make mistakes. Don’t judge them for making a mistake, help them.” One participant described the consequences of an overly rigid and punitive treatment setting: “There people are in here for that, and they kick you out for any farty little thing.”

Some participants described feeling treatment fatigue as a result of participating in so many treatment programs. As one woman noted: “After a while, you get programmed out.” This participant went on to say “… To keep shoving people in that, after a while, when you’ve had so much of it, you just get defiant and you’re just like, ‘the heck with this.’”

In contrast, other women reported that they could not follow through with the treatment recommendations because of mental health or substance use problems. One woman described the impact of her depressive symptoms on her recovery: “I’m still supposed to be doing [classes], but I’m not going. I just cannot. I isolate. I don’t talk to nobody… I don’t want to be bothered.” Another participant reported that her inability to stop alcohol use prevented her from following through with treatment: “I got released to outpatient but I didn’t follow through with the outpatient and I was still drinking…”

3.1.4. Desired Treatment

Theme 1. Addressing comprehensive needs

Because many incarcerated women suffer problems in multiple life domains, addressing these various areas was highlighted as an important aspect of treatment. Participants described that treatment should address depression, substance use, medical, and interpersonal domains. As one participant observed: “Their dual diagnosis [treatments], I guess, have a long way to go.”

Theme 2: Provision of transition supports

The time of transition back into the community was described as a period during which numerous supports and resources would be beneficial for women. Participants specified needing someone they could turn to for emotional support and for and practical support that would be helpful in securing housing and work. One participant described such a person in this way: “Just maybe programs where they can transition you, I mean transition you fully back into the world. To society. You know, maybe placing women into employment if they’re able to work, or in sober housing…” Indeed, a number of participants noted that current transition programs are insufficient in providing useful resources. An identified transition support person, as well as general pre-release planning that would bridge women to identifying jobs, housing, treatment, and medication were also identified as being important. One participant described the challenge of finding these types of resources in this way: “Just getting’ outta’ jail and transitioning, ya’ know, like into the real world. Like they don’t know how hard it is to try to get a job when you have a record and all that – just everything’- living situations, like apartments or whatever.” Other participants specified the need for financial support to access medications, obtain food, and having help with “reuniting with their children.”

Theme 3: Not wanting to be in a locked environment

Several women noted the strong desire to have housing and treatment options that were not within locked facilities. One participant explained this in the following way: “Most people, when they get out of being locked up here, they don’t want to be locked up out there… We’re grown women. We want to live normally.” Another woman stated that being in a locked treatment or housing facility felt like being in a new jail.

3.2. Results from surveys and interview notes (n = 39)

3.2.1. Circumstances surrounding first substance use

Timeline Followback data indicated that twenty-eight of the 39 women reported heavy drinking or drug use since their index release from prison; for half (14) of the 28 women, this first use occurred within approximately 8 days of prison release. For at least 6 of the 28 women, first use occurred within one day of prison release. Half of the 28 women who reported use were released to residential treatment, including 2 who used in the first week after prison release. Among the 11 women who denied any heavy drinking or drug use following release from prison, only one had a urine drug screen test positive during the larger studies.

Of the 28 who reported drug use or heavy drinking, 17 were around others who were drinking or using at the time of their first use, 8 were alone, 2 were with others who did not drink or use; and 1 did not answer. Nine were with a romantic or sexual partner or ex-partner (7 of the partners drank/used and 2 did not). Most (20) of the women who used said they had sober support in their lives at the time; women cited a variety of reasons for not reaching out for help to avoid use. When asked why they didn’t reach out to their sober network rather than use that first time, many cited reasons such as impulsive use (“I didn’t consider reaching out at all… the drug was there, so I used it”), wanting to use, and denial of risk (“I keep telling myself I’m not an alcoholic,” “I thought I could take care of myself”). One woman noted that after she returned to an old neighborhood that she had been warned not to return to, she was too embarrassed to ask for help. Other women said that people were tired of hearing their problems or they were on the street and didn’t have a phone, and another eventually did reach out and get back into recovery after a week of use.

Women on average reported feeling dysphoric rather than happy right before their first post-prison drug or alcohol use. When rating their feelings right before use on a scale from “0 = not at all” to “10 = very,” women who used (n = 27; one woman did not respond) reporting on average feeling sad/depressed (M = 5.9, SD = 4.2), lonely (M = 5.7, SD = 4.1), hopeless/discouraged (M = 5.5, SD = 4.2), and angry/frustrated (M = 5.4, SD = 3.8), although some felt happy/excited (M = 3.9 for the 27 women, SD = 3.6).

When provided with a list of 24 reasons for their first relapse taken from theories of substance use treatment in the literature (e.g., cognitive-behavioral, motivational interviewing, twelve step theories) and asked to choose the top 3 that contributed to their first post-prison drug use or heavy drinking episode, the top-chosen reasons among the 28 women who used were “being with the wrong people” (n = 13; for 5 women, the “wrong person” included a romantic partner/ex), “other” (n = 11; for 8 women write-in reasons included depression, anger, and/or guilt and shame), “not being with enough of the right people” (n = 9), “relationship problems” (n = 8), “lonely” (n = 8), and “wanted to drink/use” (n = 8; see Table 3). Very few thought that needing more treatment, lack of skills, not being ready to change, and not caring if she went back to prison contributed to her relapse.

Table 3.

Endorsement of closed-answer reasons for relapse (n = 28 who reported heavy drinking or drug use after release from prison)

| Most-endorsed reasons for relapse (from a closed-answer list) |

| Being with the wrong people (n = 13) |

| “Other” (n = 11; write-in reasons included depression, anger, and/or guilt and shame) |

| Not being with enough of the right people (n = 9) |

| Relationship problems (n = 8) |

| Lonely (n = 8) |

| Wanted to drink/use (n = 8) |

| Employment or housing problems (n = 7) |

| Went to a risky place/situation (n = 7) |

| Moderately frequently endorsed reasons for relapse (from a closed-answer list) |

| I thought I could use/drink a little and then stop (n = 6) |

| Using/drinking seemed like fun at the time (n = 5) |

| Bored (n = 5) |

| Overwhelming urges/cravings (n = 4) |

| No one keeping track of me anymore (n = 4) |

| Got discouraged about recovery and gave up (n = 3) |

| Didn’t have enough confidence (n = 3) |

| Reasons for relapse that very few women endorsed |

| Needed more intensive treatment or 12-step groups (n = 2) |

| I didn’t have goals for my life (n = 2) |

| I didn’t have the right skills (n = 2) |

| Lack of motivation for recovery (n = 2) |

| I left prison or treatment planning to use (n = 2) |

| I was not ready to change drug use/drinking (n = 2) |

| I needed money, so I was around the wrong people or illegal activities (n = 1) |

| I didn’t think I could stay sober, so I didn’t try (n = 1) |

| I didn’t care if I went back to prison (n = 0) |

3.2.2. Recovery facilitators

38 women of the 39 reported periods of non-use in the months following prison. Women were provided a list of 24 reasons that they did not drink/use during periods of sobriety that were the opposites of the reasons for first use described above. They were asked to choose the top 3 reasons they thought they were not using or drinking heavily during periods of sobriety since prison release. The most commonly chosen reasons were “I was ready for change” (n = 21), “I didn’t want to go back to prison” (n = 15), and “I spent enough time with the right people” (n=12). Women described the “right people” as professional counselors and aftercare support, other women in residential treatment, people from 12-step meetings (including sponsors), family, and positive people in sober environments. Few women said that substance use did not seem like fun, they had few/no urges/cravings, and that they were sober because they had enough money or because they had fun/meaningful non-using things to do (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Endorsement of closed-answer reasons for periods of sobriety (n = 38 of the 39 who reported having post-release periods of sobriety)

| Most-endorsed reasons for sobriety (from a closed-answer list) |

| Was ready for change (n = 21) |

| Didn’t want to go back to prison (n = 15) |

| Spent enough time with the right people (n = 12) |

| Went to treatment and/or participated in 12-step groups (n = 11) |

| I had other goals for my life (n = 11) |

| Did not want to use/drink (n = 10) |

| Avoided the wrong people (n= 9) |

| Hopeful about recovery and feeling confident (n = 9) |

| Moderately frequently endorsed reasons for sobriety (from a closed-answer list) |

| I had the skills I needed to not drink or use (n = 8) |

| Someone (parole or another person) was keeping track of me (n = 8) |

| Left prison with a solid recovery plan (n = 7) |

| I was confident I would not drink or use (n = 7) |

| Other (n = 7; medications, meetings, and accessing treatment and sober resources) |

| Was motivated for recovery (n = 6) |

| Things were going well in relationships (n = 6) |

| I avoided risky places/situations (n = 6) |

| Things were going well with employment or housing (n = 5) |

| Not lonely – had enough support and friends around (n = 5) |

| I knew I could stay clean/sober, so I worked hard at it (n = 5) |

| I knew I couldn’t drink/use even a little, so I didn’t (n = 5) |

| Reasons for sobriety that very few women endorsed |

| Using/drinking did not seem like fun (n = 3) |

| Few/no urges/cravings (n = 2) |

| Had enough money so didn’t need the ‘wrong’ people or illegal activities (n = 1) |

| Not bored – had fun/meaningful non-using things to do (n = 0) |

3.2.3. Desired treatment

When the 28 women who reported post-release substance use were asked what they would have needed to avoid drinking or using the first time, several patterns emerged from their short-answer responses. Practical support was the most commonly mentioned. Women would have liked “more help transitioning to the real world.” This included help finding housing that was safe and not near women’s old using neighborhoods, help getting needed medications, more pre-release planning, help setting up post-release mental health counseling, and help obtaining a steady job and transportation. Several mentioned that they needed someone to ask for help when they ran into obstacles so they did not get overwhelmed by these practical transition tasks. They suggested that optimally, this transitional help should involve direct mentoring rather than simply provision of “how to” information.

Other common things women said they would have needed to avoid their first post-prison substance use included avoiding problematic romantic partners, emotional support (personal counseling, someone to listen and not criticize), better or more continuity in mental health treatment, not being in such a hurry to be out of treatment (“I wish my providers had noticed I was in a hurry to quit treatment and asked me why I had reservations”), and not going back to old neighborhoods. Six women said that there is nothing anyone could have done; they had made up their minds to use and “it’s within the person to change.”

Short-answer responses provided by all 39 women about their ideal post-release treatment program overwhelming related to provision of comprehensive treatment. This comprehensive treatment would include help with relationship problems (such as “help finding myself so I don’t keep finding bad men”), group and individual counseling for mental health and substance use problems, medical care, psychiatric care (including access to medications), training or education that “can assure at least an 80% chance of job placement,” a safe home or placement in the community like a sober house that’s not a lock-in like residential treatment (“not being locked up and told what to do”), domestic violence support, family treatment, nonjudgmental support groups for women transitioning out of prison, outreach for women to transition, reminders of the consequences of use (such as death, losing children, families, or homes), help with transportation, legal assistance, help with food and clothing, encouragement, sober activities, and a focus on self-care. Recognizing that it is difficult to find such comprehensive care in one place, several women said that ideally, they would have a support person such as a recovery or transition coach to help with appointments, practical issues, counseling, and recovery.

Even when asked about their ideal post-release program, women mentioned the difficulties they face at community re-entry. As one woman said, “Women need to be forewarned that it won’t be easy getting out. I had to deal with a lot of red tape to get clothes from a social service agency. In prison they made it sound like it would be easy to get services.” One woman went further to say that support people “lie” when they say they will help and at agencies women “just get bounced around and sign a lot of paperwork.” In particular, this woman didn’t feel that help with her resume was “real” help, because as a felon she has “no options. Real help would be to have some job getting out even it if was making sandwiches for the homeless.” Another woman said that embarrassment is an obstacle to requesting help: “Housing is the number one problem getting out, but a lot of women don’t make requests for housing help because it’s embarrassing.” Finally, women said the parole board should not “punish people when they ask for help” and that ideally, post-release treatment should be outpatient rather than residential treatment and that “People need to be allowed to make mistakes and not be tossed out of program because they messed up.” Other women also emphasized the importance of a personal connection that spans the transition period: “Set people up with a sponsor and have at least one face-to-face meeting before they leave prison.”

4. Discussion

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) have identified release planning and continuity of care as key service issues for women leaving prison, asserting that imprisoned women in all countries require continuity of care for their substance use and other health (including mental health) needs. They further stated that rates of prison aftercare follow-up for women are sub-optimal, and that providing this care is critical to correcting international gender inequity in prison health (UNODC, 2009; van den Bergh et al., 2010; see also Matheson et al., 2011).

Our findings highlighted the negative synergy between MDD and substance use disorder found in other populations, especially among women (e.g., Grant, 1995; Kessler et al., 1997), for women re-entering the community from prison. Negative mood states were commonly cited precipitants of relapse in our sample, especially discouragement or hurt feelings, although a small minority of women described using substances to “celebrate.” Incarcerated women around the world tend to be vulnerable; MDD and high rates of trauma (80% in this sample) contribute to periods of strong negative affect (Bardeen and Read, 2010; Bradley et al., 2011). It may be helpful for prison and aftercare programs to provide women with help managing or reducing uncomfortable feelings (e.g., hurt, loneliness, discouragement, depression, or anxiety) without substance use by teaching affect regulation skills, improving social support, using validation and empathy rather confrontional treatment techniques, and supplying needed psychiatric or addiction pharmacotherapy. In particular, although limit-setting is necessary, aftercare treatment that was overly punitive (such as treatment providers yelling at or criticizing women) exacerbated dysphoric feelings and led some women to flee residential treatment facilities that did not feel safe with little thought about where they were going next. Trauma-informed prison care and aftercare are important for this population (Cellucci & Pelton, 2011; Kubiak, 2004; Maloney & Moller, 2009).

Findings also add to the literature (Chandler et al., 2009; Luther et al., 2011; Matheson, 2011; Mallik-Kane & Visher, 2008; Richie, 2001; UNODC, 2009) highlighting the critical importance and vulnerability of the re-entry transition period. Half of the women in our sample who used or drank heavily did so within 8 days of prison release, several within the first day, suggesting that delays in accessing care post-release are risky. Although a few women left prison intending to drink or use drugs, the first use for most was unexpected and impulsive; some women encountered drugs in the car or bus ride home from prison. Provision of access to care (or contact with a provider, sponsor, or recovery coach they already know and trust) within hours or a day of being released may be an essential ingredient of aftercare.

Although most women had some source of support for sobriety in their lives at the time of their first post-prison substance use, many did not utilize this support because they used impulsively, wanted to use, denied risk, or were embarrassed to ask for help after doing something they had been warned not to do. Because many women may not ask for help in the moment, aftercare programs should be willing to help women who have already used or experienced significant challenges before they attend their first aftercare appointment. In addition, encouragement and active connection to sober, supportive others may be particularly important to women with co-occurring depression, who are prone to feeling discouraged or not wanting to reach out for support. For example, women said they were more likely to attend self-help meetings if they didn’t have to go alone. Active emotional and practical support may help women tolerate unfamiliar circumstances and help keep them from becoming overwhelmed with the myriad demands of re-entry.

In addition to non-judgmental support for sobriety, women described other recovery facilitators that helped them avoid use at least some of the time. They described abstinence and therapeutic work done in prison (such as increasing motivation and confidence to stay sober, self-awareness, better self-care) and continued urine drug screen monitoring after release as helpful to maintaining recovery. Avoiding known relapse triggers (such as drugs or a toxic relationship) was mentioned as important. Feeling that they were having success in finding safe housing and work also helped women maintain sobriety; discouragement with slow progress in these practical aspects was mentioned as a relapse precipitant.

Consistent with aftercare recommendations for other populations of re-entering women prisoners (Grella & Greenwell, 2007; UNODC, 2009), participants in this study were clear that the assistance that wanted and needed covered diverse aspects of their lives (substance use, mental health, medical, relationship issues, family issues including family reunification, opportunities to address partner violence, housing, employment, food, clothing, legal assistance). They were also clear that negotiating access to so many different services from different locations was challenging and could facilitate relapse. They wanted in-prison care to be more realistic about the practical difficulties of the transition period. They expressed a clear desire for more “hands-on” help transitioning to the “real world,” preferably from a single person (such as a case manager, mentor, or “recovery coach”), who would be able to help them make treatment appointments and coordinate the myriad practical and treatment challenges they faced. Ideally, links to comprehensive care or at least a person who the woman trusts to provide real, hands-on help should occur before the woman left prison. In fact, desire for an identified transition support person and more active, multifaceted pre-release planning were two of the most commonly mentioned themes.

A strength of this study is that it provides the perspectives of a vulnerable population whose needs often differ from their more studied male counterparts. It is the first study of which we are aware to examine the circumstances of first substance use following release from prison among women with co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders, providing detailed, specific information about re-initiation of substance use during this vulnerable period. Furthermore, given the opportunity to explain what they thought would be helpful, participants offered researchers and clinicians many specific details about an ideal treatment program, providing insight into the struggles and treatment needs of a high-risk, understudied population.

The study also has limitations. The sample is small. Participants came from prisons in two Northeastern U.S. states and it is unclear how results translate to other areas of the world. Because qualitative interviews were conducted to better understand phenomena observed in a treatment study, they were added to the study post hoc, meaning that interviews took place at varying lengths of time after prison release and 5 of the original 20 interviews were not recorded. Finally, participants in this study received 8 weeks of additional MDD-focused group treatment in prison, which may have influenced women’s explanations of the reasons for their relapse and recovery. However, study intervention was limited to 3 hours per week of mental health groups with no connection to other prison services. Therefore, participants’ experience of incarceration, re-entry planning, and the re-entry process were standard for the prison and were not affected by study participation.

Results point to the importance of helping depressed, substance using women prisoners reduce or manage negative affect, improve relationships, and obtain active and smooth transitional support. Qualitative interviews with providers underscored these findings and elaborated on service delivery challenges and options for providing better continuity of care between prison and community (Johnson et al., under review a). Our team has begun to test interventions to improve mood and relationships in the re-entry period (Johnson & Zlotnick 2012; Johnson & Zlotnick, 2008). We have also begun to test the feasibility of various in-reach and out-reach strategies for helping women bridging the transition from prison to the community, such as bringing community agencies into correctional facilities to meet women before they are released (Johnson et al., in press) and providing women with cell-phones to call prison counselors and other resources as needed in the risky days and weeks after release (Johnson et al., under review b). Additional research on low-cost, accessible, continuous, comprehensive transitional services for women with co-occurring disorders leaving prison is needed.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the U.S. National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA; K23 DA021159). NIDA had no role in the study design, conduct, or reporting of results.

Biographies

Dr. Johnson is an Associate Professor (Research) who conducts research on mental health and substance use treatments for incarcerated women.

Dr. Chatav is an Assistant Professor (Research).

Dr. Nargiso is a clinician and researcher.

Dr. Kuo is an Assistant Professor (Research).

Ms. Shefner is a student.

Ms. Williams is a research assistant.

Dr. Zlotnick is a Professor (Research).

Contributor Information

Jennifer E. Johnson, Department: Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University/Institution: Brown University, Town/City: Providence, State (US only): RI, Country: USA

Yael Chatav Schonbrun, Department: Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University/Institution: Brown University, Town/City: Providence, State (US only): RI, Country: USA

Jessica E. Nargiso, Department: Psychiatry, University/Institution: Massachusetts General Hospital, Town/City: Boston, State (US only): MA, Country: USA

Caroline C. Kuo, Department: Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, University/Institution: Brown University, Town/City: Providence, State (US only): RI, Country: USA

Ruth T. Shefner, Department: Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University/Institution: Brown University, Town/City: Providence, State (US only): RI, Country: USA

Collette A. Williams, Department: Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University/Institution: Brown University, Town/City: Providence, State (US only): RI, Country: USA

Caron Zlotnick, Department: Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University/Institution: Brown University, Town/City: Providence, State (US only): RI, Country: USA

References

- Adams S, Leukefeld CG, Peden AR. “Substance abuse treatment for women offenders: A research review”. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2008;Vol. 19:61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen JR, Read JP. “Attentional control, trauma, and affect regulation: A preliminary investigation”. Traumatology. 2010;Vol 16:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley B, DeFife JA, Guarnaccia C, Phifer J, Fani N, Ressler KJ, Westen D. “Emotion dysregulation and negative affect: Association with psychiatric symptoms”. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011;Vol 72:685–691. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06409blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benda BB. “Gender differences in life-course theory of recidivism: A survival analysis”. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2005;Vol. 49:325–342. doi: 10.1177/0306624X04271194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Lindsay RG, Stern MF. “Risk factors for all-cause, overdose and early deaths after release from prison in Washington state.”. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;Vol. 117:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonczar TP. “National Corrections Reporting Program: Sentence length by offense, admission type, sex, and race, 2009”. [accessed 6 December 2012];Bureau of Justice Statistics Reporting Program. 2011 available at: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=2056.

- Bottlender M, Soyka M. “Efficacy of an intensive outpatient rehabilitation program in alcoholism: predictors of outcome 6 months after treatment”. European Addiction Research. 2005;Vol. 11(No. 3):132–137. doi: 10.1159/000085548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady TM, Krebs CP, Laird G. “Psychiatric comorbidity and not completing jail-based substance abuse treatment”. American Journal on Addiction. 2004;Vol. 13:83–101. doi: 10.1080/10550490490265398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead W, Blazer D, George L, Tse C. “Depression, disability days and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiological survey”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;Vol. 264:2524–2528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Evans DM, Miller IW, Burgess ES, Mueller TI. “Cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in alcoholism”. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;Vol. 65:715–726. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Monti PM, Myers MG, Martin RA, Rivinus T, Dubreuil ME, Rohsenow DJ. “Depression among cocaine abusers in treatment: relation to cocaine and alcohol use and treatment outcome”. American Psychiatric Association. 1998;Vol. 155:220–225. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cellucci T, Peltan JR. “Childhood sexual abuse and substance abuse treatment utilization among substance-dependent incarcerated women,”. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2011;Vol 41:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND. “Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: improving public health and safety,”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;Vol 301:183–190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC. “Natural change and the troublesome use of substances: A life-course perspective”. In: Miller WR, Carroll KM, editors. Rethinking Substance Abuse: What the Science Shows, and What We Should Do About It. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Drug War Facts. [accessed 6 December 2012];Women & the drug war. Get the Facts: DrugWarFacts.org. 2012 available at: http://www.drugwarfacts.org/cms/Women.

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders: Patient Edition. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF. “Comorbidity between DSM-IV drug use disorders and major depression: Results of a national survey of adults,”. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1995;Vol. 7:481–497. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Brooks A, Gordon S, Green C, Kropp F, McHugh R, et al. “Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature”. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;Vol. 86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Greenwell L. “Treatment needs and completion of community-based aftercare among substance-abusing women offenders,”. Women’s Health Issues. 2007;Vol. 17:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerino P, Harrison PM, Sabol WJ. “Prisoners in 2010”. U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2011 December 2011, NCJ 236096. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Depression runs in families: the social context of risk and resilience in children of depressed mothers. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. “Rating depressive patients.”. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1980;Vol. 41(12,Sec2):21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins DC, el Guebaly N, Armstrong S. “Prospective and retrospective reports of mood states before relapse to substance use”. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;Vol. 63:400–407. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Schonbrun YC, Peabody M, Shefner RT, Fernandes K, Rosen RK, Zlotnick C. Provider experiences with prison care and aftercare for women with co-occurring disorders. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9397-8. under review a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Schonbrun YC, Stein MD. Pilot test of twelve-step linkage for alcohol abusing women leaving jail. Substance Abuse. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2013.794760. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Williams C, Zlotnick C. Development and pilot testing of a cellphone-based transitional intervention for women prisoners with comorbid substance use and depression. doi: 10.1177/0032885515587466. under review b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Zlotnick C. “Pilot study of treatment for major depression among women prisoners with substance use disorder”. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;Vol. 46(No. 9):1174–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Zlotnick C. “A pilot study of group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in substance abusing female prisoners”. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;Vol. 34:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. “Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey,”. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;Vol. 54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O’Grady KE. “A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: Results at 12 months post-release”. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;Vol. 37:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD. “A 2.5 year follow-up of depression, life crises, and treatment effects on abstinence among opioid addicts”. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;Vol. 43(No. 8):733–738. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800080019003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak SP. “The effects of PTSD on treatment adherence, drug relapse, and criminal recidivism in a sample of incarcerated men and women,”. Research on Social Work Practice. 2004;Vol. 14:424–433. [Google Scholar]

- Langan NP, Pelissier BMM. “Gender differences among prisoners in drug treatment”. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;Vol. 13:291–301. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther JB, Reichert ES, Holloway ED, Roth AM, Aalsma MC. “An exploration of community re-entry needs and services for prisoners: A focus on care to limit return to high-risk behavior,”. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2011;Vol. 25:475–481. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik-Kane K, Visher CA. “Health and Prisoner Reentry: How Physical, Mental, and Substance Abuse Conditions Shape the Process of Reintegration,”. Urban Institute: Justice Policy Center. 2008 Accessed on 3/1/2013 at http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/411617_health_prisoner_reentry.pdf.

- Matheson FI, Doherty S, Grant BA. “Community-based aftercare and return to custody in a national sample of substance-abusing women offenders.”. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;Vol. 101:1126–1132. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Pettinati HM, Morrison R, Feeley M, Mulvaney FD, Gallop R. “Relation of depression diagnoses to 2-year outcomes in cocaine-dependent patients in a randomized continuing care study”. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;Vol. 16:225–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick G, Coen C, Taxman FS, Sacks S, Zinsser KM. “Community-based co-occurring disorder (COD) intermediate and advanced treatment for offenders”. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2008;Vol. 26(No. 4):457–473. doi: 10.1002/bsl.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina NP, Burdon WM, Prendergast ML. “Assessing the needs of women in institutional therapeutic communities”. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2003;Vol. 37:89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Messina N, Burdon W, Hagopian G, Prendergast M. “Predictors of prison-based treatment outcomes: A comparison of men and women participants”. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2006;Vol. 32:7–28. doi: 10.1080/00952990500328463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller LF, Matic S, van den Bergh BJ, Moloney K, Hayton P, Gatherer A. “Acute drug-related mortality of people recently released from prisons”. Public Health. 2010;Vol. 124:637–639. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moloney KP, Moller LF. “Good practice for mental health programming for women in prison: Reframing the parameters,”. Public Health. 2009;Vol 123(6):431–433. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale J, Allen D, Coombes L. “Qualitative research methods within the addictions”. Addiction. 2005;Vol. 100:1584–1593. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan K, Rynne C, Miller J, O’Sullivan S, Fitzpatrick V, Hux M, et al. “A follow-up study on alcoholics with and without co-existing affective disorder”. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;Vol. 152:813–819. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.6.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelissier BMM, Camp SD, Gaes GG, Saylor WG, Rhodes W. “Gender differences in outcomes from prison-based residential treatment”. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;Vol. 24:149–160. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelissier B, Jones N, Cadigan T. “Drug treatment aftercare in the criminal justice system: A systematic review”. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;Vol. 32(No. 3):311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelissier B, O’Neil JA. “Antisocial personality and depression among incarcerated drug treatment participants”. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;Vol. 11:379–393. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, Baker M, Burns T, Lilford RJ, Muijen M. “Reflections on Methodological issues in mental health research”. Journal of Mental Health. 2000;Vol. 9:463–470. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson K, Baillie A, Reid S, Morley K, Teesson M, Sannibale C, et al. “Do acamprosate or naltrexone have an effect on daily drinking by reducing craving for Alcohol?”. Addiction. 2008;Vol. 103(No. 6):953–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie BE. “Challenges incarcerated women face as they return to their communities: Findings from life history interviews,”. Crime and Delinquency. 2001;Vol. 47:368–389. [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Kosten TR, Weissman MM, Kleber HD. “Prognostic significance of psychopathology in treated opiate addicts”. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;Vol. 43(No. 8):739–45. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800080025004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Dolinsky ZS, Babor TF, Meyer RE. “Psychopathology as a predictor of treatment outcome in alcoholics”. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;Vol. 44:505–13. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabol WJ, West HC, Cooper M. “Prisoners in 2008”. U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. 2009 December 2009, NCJ 228417. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks S, Chaple M, Sacks JY, McKendrick K, Cleland CM. “Randomized trial of a re-entry modified therapeutic community for offenders with co-occurring disorders: Crime outcomes,”. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;Vol. 42:247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson L, Singh R, Barua P. “Qualitative research as a means of intervention development”. Addiction Research and Theory. 2001;Vol. 9:587–599. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JD, Hickcox M. “First lapses to smoking: Within-subjects analysis of real-time reports”. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;Vol. 64:366–379. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. In: Time line follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. Litten R, Allen J, editors. Totowa New Hampshire: Measuring Alcohol Consumption, Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Qiu J, Saber-Tehrani AS, Altice FL. “Retention on buprenorphine is associated with high levels of maximum viral suppression among HIV-infected opioid dependent released prisoners.”. PLoS ONE. 2012;Vol. 7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038335. ArtID e38335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME, Salloum IM, Cornelius JD. “Comorbid alcoholism and depression: treatment issues”. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;Vol. 62(No. 20):32–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Women’s health in prison: correcting gender inequity in prison health. 2009 Accessed 2/5/13 at http://www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0004/76513/E92347.pdf.

- van den Bergh BJ, Moller LF, Hayton P. Women’s health in prisons: it is time to correct gender insensitivity and social injustice. Public Health. 2010;124(11):632–634. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley R. World prison population list. London: King’s College London International Centre for Prison Studies; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Klerman G, Paykel ES, Prusoff B, Hanson B. “Treatment effects on the social adjustment of depressed patients”. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1974;Vol. 30(No. 8):771–778. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760120033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. “Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: That was Zen, this is Tao”. American Psychologist. 2004;Vol. 59:224–235. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Clarke JG, Friedmann PD, Roberts MB, Sacks S, Melnick G. “Gender differences in comorbid disorders among offenders in prison substance abuse treatment programs”. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2008;Vol. 26:403–412. doi: 10.1002/bsl.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zywiak W, Stout RL, Trefry WB, Connors GJ, Westerberg VS, Maisto SA, Glasser I. “Alcohol relapse repetition, gender, and predictive validity”. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;Vol. 30(No. 4):349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]