Abstract

Passage of blood through a sorbent device for removal of bacteria and endotoxin by specific binding with immobilized, membrane-active, bactericidal peptides holds promise for treating severe blood infections. Peptide insertion in the target membrane and rapid/strong binding is desirable, while membrane disruption and release of degradation products to the circulating blood is not. Here we describe interactions between bacterial endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) and the membrane-active, bactericidal peptides WLBU2 and polymyxin B (PmB). Analysis of the interfacial behavior of mixtures of LPS and peptide using air-water interfacial tensiometry and optical waveguide lightmode spectroscopy strongly suggests insertion of intact LPS vesicles by the peptide WLBU2 without vesicle destabilization. In contrast, dynamic light scattering (DLS) studies show that LPS vesicles appear to undergo peptide-induced destabilization in the presence of PmB. Circular dichroism spectra further confirm that WLBU2, which shows disordered structure in aqueous solution and substantially helical structure in membrane-mimetic environments, is stably located within the LPS membrane in peptide-vesicle mixtures. We therefore expect that presentation of WLBU2 at an interface, if tethered in a fashion which preserves its mobility and solvent accessibility, will enable the capture of bacteria and endotoxin without promoting reintroduction of endotoxin to the circulating blood, thus minimizing adverse clinical outcomes. On the other hand, our results suggest no such favorable outcome of LPS interactions with polymyxin B.

Keywords: cationic amphiphilic peptides, WLBU2, polymyxin B, lipopolysaccharide, endotoxin, sepsis, interfacial tensiometry

Introduction

Severe sepsis is a blood infection that in the US alone affects about 750,000 people each year, killing 28-50% of them[1-3]. The number of sepsis-related deaths continues to increase, and is already greater than the annual number of deaths in the US from prostate cancer, breast cancer and AIDS combined. During bacterial growth or as a result of the action of antibacterial host factors, lipopolysaccharide (LPS, endotoxin) is released from the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. The high immunostimulatory potency of endotoxin causes dysregulation of the inflammatory response with elevated production and release of proinflammatory cytokines[4], leading to blood vessel damage and organ failure[1, 2].

Hemoperfusion, involving passage of blood through a sorbent device for the removal of selected targets, holds promise for treating sepsis[5-7]. Toraymyxin™, a commercial hemoperfusion device, has been used clinically in Japan since 1994 for removal of endotoxinby specific binding with the immobilized antimicrobial peptide polymyxin B (PmB), and was introduced to the European market in 2002[8]. However, such devices have not been widely adopted elsewhere, as clinical trials have shown little significant change in either endotoxin or cytokine concentrations, or in incidence of mortality[7, 9]. Several studies further indicated that hemoperfusion results in significant depletion of both white blood cells and platelets [10, 11]. PmB is covalently attached to a polystyrene fiber matrix within such devices, and it is fair to expect that immobilization in that way would strongly inhibit peptide mobility, accessibility, and activity[12-14]. In addition, nonspecific loss of blood protein, platelets and cells through interaction with the otherwise unprotected polystyrene surface is likely. The clinical utility of PmB itself has been limited due to nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity, monocyte stimulation (IL-1 release), and substantial blood protein losses can occur during operation of devices with immobilized PmB[5, 6, 15, 16]. In addition, PmB resistance among common pathogens is not rare[17].Successful hemoperfusion for sepsis treatment will require surface modification that will ensure highly selective capture of bacteria and endotoxin that reach the interface. In addition, surface coatings must provide pathogen binding functionality without evoking a host cell response, without nonspecific adsorption of protein, and without platelet activation and blood cell damage caused by cell-surface interactions.

Cationic amphiphilic peptides (CAPs) constitute a major class of antimicrobials that allow neutrophils and epithelial surfaces to rapidly inactivate invading pathogens[18, 19]. A number of CAPs have been shown to bind LPS with affinities comparable to PmB[20, 21]. For example, the CAP human cathelicidin peptide LL-37 has been shown to neutralize the biological activity of LPS and to protect rats from lethal endotoxin shock, revealing no statistically significant differences in antimicrobial or anti-endotoxin activities between LL-37 and PmB[22]. Despite the broad activity of LL-37 and other natural CAPs, their potency is inhibited in the presence of physiological concentrations of NaCl and divalent cations. However the 24-residue, de novo engineered peptide WLBU2, a synthetic analogue of LL-37, shows highly selective, potent activity against a broad spectrum of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria at physiologic NaCl and serum concentrations of Mg2+and Ca2+[23-26]. Moreover WLBU2 shows greater antimicrobial activity than either LL-37 or PmB, and is active against a much broader spectrum of bacteria [27, 28].

A major distinguishing feature of CAPs is their capacity to adopt an amphiphilic secondary structure in bacterial membranes, typically involving segregation of their positively-charged and hydrophobic groups onto opposing faces of an α-helix[18]. The propensity for α-helix formation in cell membranes correlates positively with CAP activity and selectivity of bacterial over human cells, and WLBU2 has been optimized specifically for formation of an amphipathic α-helix conformation in cell membranes[23-25, 28]. Finally, in addition to its broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity in blood, WLBU2 retains potency while bound to solid surfaces[14, 26, 27, 29, 30] and importantly, shows high affinity for adhesion of susceptible bacteria [27].

In this paper we describe the outcomes of a comparative study of molecular interactions of WLBU2 and PmB with LPS. Analysis of the competitive adsorption behavior of peptide and LPS recorded with optical waveguide lightmode spectroscopy (OWLS) and interfacial tensiometry, and analysis of peptide structure and particle size distribution in peptide-vesicle suspensions with circular dichroism (CD) and dynamic light scattering (DLS), were used to evaluate differences in the stability of peptide-vesicle association, and hence the associated potential of each peptide for use in hemoperfusion for endotoxin removal.

Materials and Methods

Peptides and Lipopolysaccharides

Unless otherwise specified, all reagents were purchased from commercial vendors and were of analytical reagent or higher grade. WLBU2 (RRWVRRVRRWVRRVVRVVRRWVRR, 3400.1 Da) was obtained from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). Polymyxin B sulfate (PmB, 1385.6 Da) and purified Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). All solutions were prepared using HPLC-grade water, and all peptides and LPS were used as received, without further purification.

Stock solutions of WLBU2 were made in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 10 mM sodium phosphate with 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.4), or in 0.5M HClO4 for circular dichroism. Working solutions at 50 μM or 5 μM concentrations were prepared in degassed PBS, using the calculated molar extinction coefficient at 280 nm (16,500 M-1 cm-1) of WLBU2 [31]. Similarly,10 mg/mL stock solutions of PmB in degassed PBS were diluted to 50 μM or 5 μM. LPS was dissolved in PBS to 10 mg/mL, and diluted to 0.1 mg/mL in degassed PBS. All dilute peptide/LPS solutions were prepared and degassed under vacuum with sonication immediately before use.

Surface Modification of OWLS Sensors

SiO2-coated OW2400cOWLS waveguides(MicroVacuum, Budapest, Hungary) were cleaned by submersion in 5% w/v sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for thirty minutes, followed by 10 min at 80 °C in 5:1:1 H2O:27% HCl:30% H2O2,then rinsed with HPLC H2O and dried under a stream of N2[32].Cleaned waveguide surfaces were modified with trichlorovinylsilane (TCVS, TCI America, Portland, OR) by a variation of the method of Popat[33-35]. Briefly, clean OWLS sensors were exposed to flowing dry N2in a sealed vessel for 1 hr to remove any residual surface moisture, after which 200 μL of TCVS was added and allowed to vaporize at 25 °C, while flowing N2 transportedthe TCVS vapor across the waveguide surfaces. The N2 flow was maintained for three hours, after which the sensors were cured at 120 °C for 30 min to stabilize the vinylsilane layer. Cleaned and modified sensors were stored in 1.5 mL centrifuge vials under N2 in the dark to prevent oxidation of the vinyl moieties.

Optical Waveguide Lightmode Spectroscopy

Silanized wave guides were equilibrated prior to use by incubation overnight in PBS [36], then rinsed with HPLC H2O, dried with N2, and immediately installed in the flow cell (4.8 uL total volume) of a MicroVacuum OWLS 210 instrument (Budapest, Hungary) equipped with a 4 mL narrow-bore Tygon® flow loop in line with the flow cell. Incoupling peak angles (±TE and TM) were recorded about four times per minute at 20 °C, and a stable baseline was achieved with PBS prior to the injection of peptide or LPS. Unless otherwise indicated, flow rates were maintained at 50 μL/minduring adsorption and elution steps. Peptides and LPS were introduced as mixtures (competitive adsorption) for 40 minutes, followed by a 40-minute rinse with flowing PBS.

Interfacial tensiometry

A FTÅ model T10 (First Ten Ångstroms, Portsmouth, VA) equipped with a Du Nuöy ring (CSC Scientific Co, Fairfax, VA) was used to measure the baseline surface tension of 6.5 mL of PBS, after which 500 μL of peptide or LPS stock solution was injected to reach final concentrations of 5 or 50 μM WLBU2 or PmB in PBS, with or without 0.1 mg/mL LPS. Data was collected for at least 20 min to determine the steady state surface tension of the resulting peptide and/or LPS solutions. The platinum ring was flamed to remove contaminants between experiments.

Dynamic Light Scattering

Apparent particle sizes of peptide and LPS solutions and mixtures were measured at 20 °C by dynamic light scattering (DLS) at 635 nm, using a Brookhaven Instruments 90 Plus Particle Size Analyzer (Holtsville, NY). Ten 1-minute scans were averaged for each sample, and cumulative size distributions extracted from the multimodal size distribution data.

Circular Dichroism

Peptide secondary structure in the presence or absence of LPS was evaluated in triplicate by circular dichroism (CD) using a Jasco J-815 spectropolarimeter (Easton, MD) at 25 °C. Spectra were recorded in a cylindrical cuvette (0.1 cm pathlength) from 185 to 260 nm in 0.5 nm increments after calibration with 0.6 mg/mL D(+)-camphorsulfonic acid, and 10 scans/sample were averaged to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. All concentrations of peptides and LPS were the same as for tensiometry and OWLS. The spectra from each of the three replicates for each sample differed only slightly (∼5%) in signal intensity;representative spectra are shown throughout. Peptide α-helix content was estimated from CD spectra using Dichro Web[37, 38].

Results and Discussion

Competitive adsorption of peptides and LPS at the air-water interface

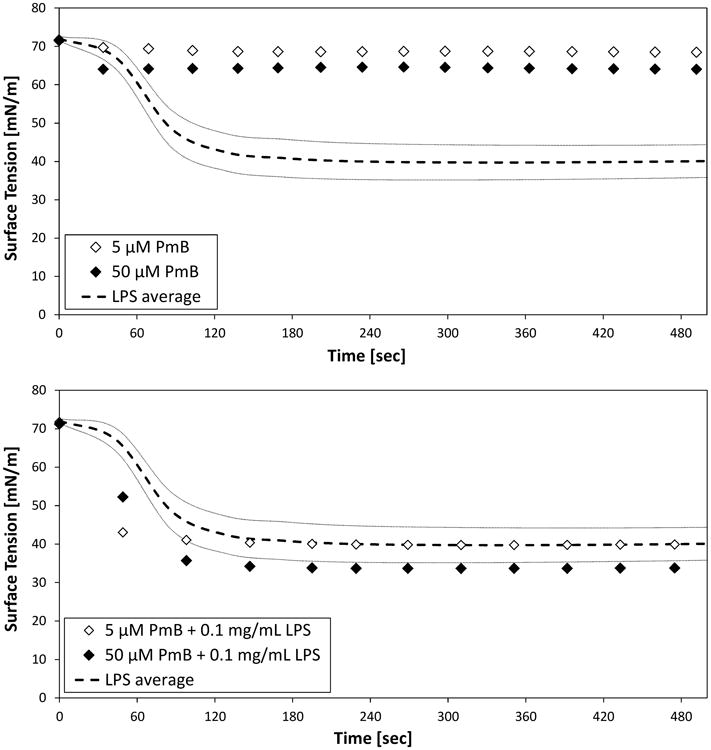

Surface tension depression was recorded for mixtures of LPS (0.1 mg/) and peptide at high (50 μM) or low (5 μM) peptide concentrations in buffer (Figures 1 and 2). In the absence of peptide, LPS vesicles decreased surface tension to a steady value of about 40 mN/m. In contrast, while 50 μM PmB slightly reduced surface tension, PMB had almost no effect on surface tension at 5 μM (Fig. 1, top). However, when PmB is mixed with LPS, a faster rate of surface tension decrease is observed at each concentration, and, in the case of 50 μMPmB, the surface tension is reduced to a greater extent than observed with LPS alone (Fig. 1, bottom).

Fig. 1.

Air-water tensiometry of suspensions of 5 or 50 μMPmBand 1.0 mg/mL LPS in PBS, as individual species (top) and as mixtures of peptide and LPS (bottom). Average values (- - -) and standard deviation (n =5, gray lines) are shown for LPS.

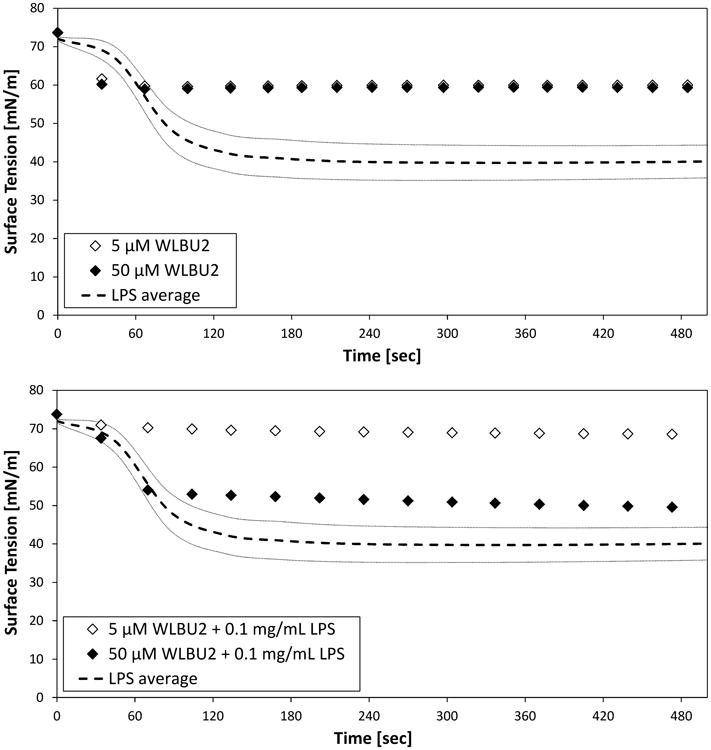

Fig. 2.

Air-water tensiometry of suspensions of 5 or 50 μM WLBU2 and 1.0 mg/mL LPS in PBS, as individual species (top) and as mixtures of peptide and LPS (bottom). Average values (- - -) and standard deviation (n =5, gray lines) are shown for LPS.

As with PmB, WLBU2 in the absence of LPS did not substantially decrease surface tension at either concentration (Fig. 2, top). However, unlike PmB, the similarity in the rate and extent of surface tension depression at each WLBU2 concentration suggests that monolayer coverage of the interface is achieved in each case.

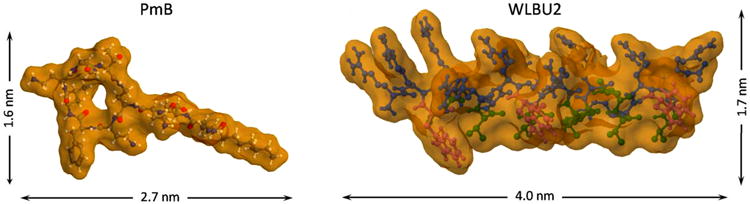

The dimensions of the peptides were determined using the open-source viewer Jmol™[39] from structures of PmB from the NCBI PubChem repository (CID 49800003),and a helical structure ofWLBU2 predicted using PEP-Fold [40, 41] (Fig. 3). From those dimensions, the expected surface concentrations of PmB and WLBU2 peptides adsorbed in a monolayer in a “side-on” or “end-on” conformation were estimated, assuming a footprint of the solution dimensions and close-packed rectangular (side-on) or hex-packed circular (end-on) configurations (Table 1). The ratio of the surface tension depression for WLBU2 relative to PmB (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, top panels) is about 3.23 at 5 μM peptide, and about 1.55 at 50 μM peptide. These values fall within limits based on expectations for monolayer coverage.

Fig. 3.

Molecular structure and approximate dimensions of PmB (left) and helical form of WLBU2 (right) peptide.

Table 1.

Size and estimated packing density of PmB and WLBU2 adsorbed “side-on” and “end-on” at an interface. Dimensions were estimated from published (PmB) or predicted (WLBU2) molecular structures.

| Peptide | MW (Da) | Length (nm) | Width(nm) | “Side-On” Monolayer (ng/cm2) | “End-On” Monolayer (ng/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PmB | 1385.6 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 53 | 86 |

| WLBU2 | 3400.1 | 4.0 | 1.7 | 83 | 180 |

Mixtures of LPS and WLBU2 behave quite differently from the mixtures of PmB and LPS (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, bottom panels). In particular, the presence of WLBU2 with LPS results in appreciably reduced surface tension depression when compared to LPS alone (Fig. 2, bottom). At the low (5 μM) concentration of WLBU2, the surface tension depression is nearly negligible compared to that associated with either WLBU2 or LPS alone. At higher (50 μM) WLBU2 concentrations in an LPS-WLBU2 mixture, the surface tension was depressed substantially, but did not reach that of LPS alone.

These results strongly suggest that suspensions of LPS with WLBU2 are more stable than similar suspensions of LPS with PmB. In particular, suspensions of LPS with WLBU2 show substantially less surface activity (e.g., vesicle adsorption and spreading at the interface) than is exhibited by LPS alone (Fig. 2, bottom). In contrast, suspensions of LPS with polymyxin B show greater surface activity than is observed for LPS alone (Fig. 1, bottom).

These findings are potentially consistent with the notion that peptide insertion (into the vesicle membrane) and stabilization of intact LPS vesicles occurs in the case of WLBU2, while peptide-induced destabilization of LPS vesicles occurs in the case of PmB. We further tested this hypothesis by evaluating the adsorption behavior of peptide-LPS mixtures at a hydrophobic solid surface, and observation of peptide 2° structure and particle size distributions in such mixtures.

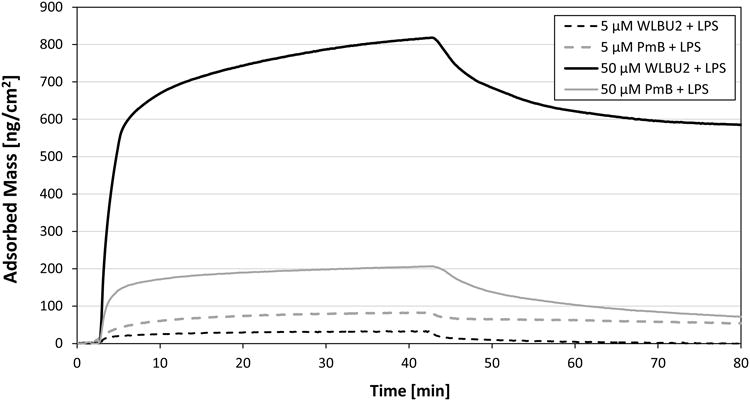

Competitive adsorption of peptides and LPS at a hydrophobic solid surface

Fig. 4 shows the adsorption and elution kinetics recorded with mixtures of LPS (0.1 mg/mL) and peptide at high (50 μM) or low (5 μM) peptide concentrations. The total mass remaining after elution was similar for both mixtures containing PmB, with final adsorbed masses of 74 or 55 ng/cm2, respectively. The adsorption kinetics of LPS in the presence of PmB (Fig. 4) are also consistent with the tensiometry results of Fig. 1, and suggest that destabilized LPS vesicles adsorb and spread at the interface.

Fig. 4.

OWLS kinetic data for competitive adsorption from mixtures of LPS (0.1 mg/mL) and peptide at low (5 μM) and high (50 μM) peptide concentrations.

In contrast, the final adsorbed massesafter elution for mixtures containing 0.1 mg/mL LPS and 5 or 50 μM WLBU2 were substantially different. The final adsorbed mass was nearly zero at the low peptide concentration, but reached 590 ng/cm2 with 50 μM WLBU2. The observation of extremely low surface activity (i.e. adsorbed amounts) in WLBU2-LPS mixtures at low peptide concentration is consistent with the tensiometry results (Fig. 2, bottom). It also suggests that LPS vesicles formed under these conditions are less able to spread at the hydrophobic surface, presumably due to their association with the membrane-active peptide WLBU2. The reason for the high value of adsorbed mass remaining after elution in the case of the 50 μM WLBU2-LPS mixture is not obvious. With reference to Fig. 2 (bottom), however, the high adsorption would not be consistent with any enhancement of LPS vesicle spreading at the interface. Rather, it suggests that intact WLBU2-associated LPS vesicles are adsorbed at the solid-liquid interface, without spreading.

Peptide structure in peptide-LPS mixtures

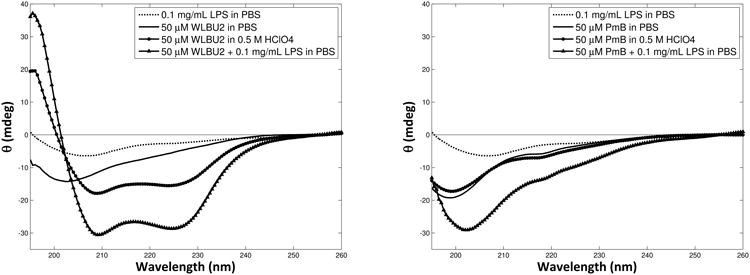

WLBU2 structure is substantially disordered in aqueous solution, but becomes increasingly helical in the presence of certain anions (e.g. ClO4–)[42], membrane-mimetic solvents, or bacterial membranes. For example, Deslouches et al. (2005b) showed that WLBU2 has no appreciable stable structure in water, but reaches 81% α-helix content in an ideal membrane mimetic solvent (30% trifluoroethanol in phosphate buffer)[25]. Circular dichroism shows that WLBU2 gains substantial helicity when mixed with LPS (Fig. 5, left), reaching 78% α-helix content. This strongly suggests that the peptide is located almost exclusively within the membranes of the LPS vesicles. Due to its rigid cyclic structure, PmB would not be expected to become substantially α-helical, and in fact shows no appreciable helical structure under any conditions (Fig. 5, right). The CD spectrum from the PmB-LPS mixture appears to be primarily the sum of the CD signal from PmB and LPS alone.

Fig. 5.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of 50 μM WLBU2 (left) or PmB (right) in PBS, with helix-inducing perchlorate ions (0.5 M), or in the presence of LPS vesicles (0.1 mg/mL).

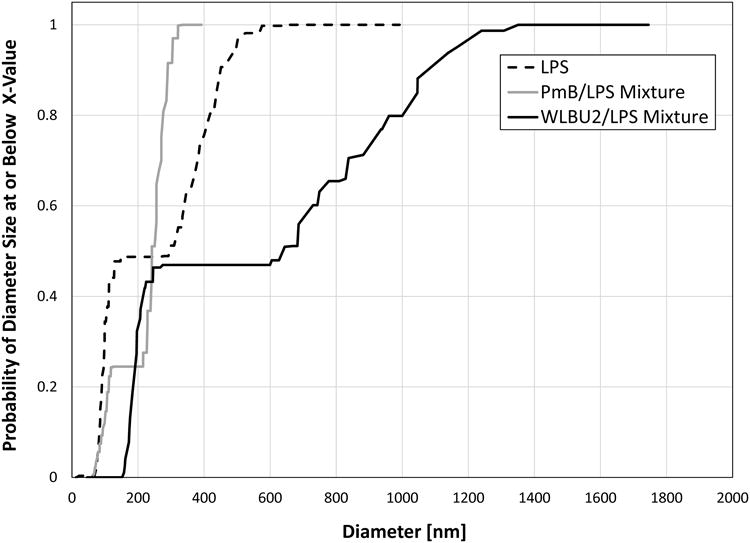

Vesicle size distribution in peptide-LPS mixtures

Dynamic light scattering analysis of peptide-LPS mixtures and peptide-free LPS suspensions are presented in Fig. 6 as the cumulative oversize distribution of particle diameter. The particle size distribution was bimodal in all cases. At the lower mode, the presence of WLBU2 increased the apparent particle diameter of LPS, from 95±11 nm to 195±13 nm (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3), while addition of PmB had very little effect on particle size in the lower mode (89±19 nm). At the upper mode, however, the presence of PmB decreased the mean particle diameter from 408±56 nm to 262±26 nm, consistent with disruption of the LPS vesicles. In contrast, the presence of WLBU2 greatly increased both the mean and the range of particle sizes, with a mean diameter of 909±204 nm. This increase in particle size and polydispersity suggests that WLBU2 induces aggregation of LPS vesicles.

Fig. 6.

Cumulative oversize distribution of particle diameter in peptide-LPS suspensions from dynamic light scattering (DLS).

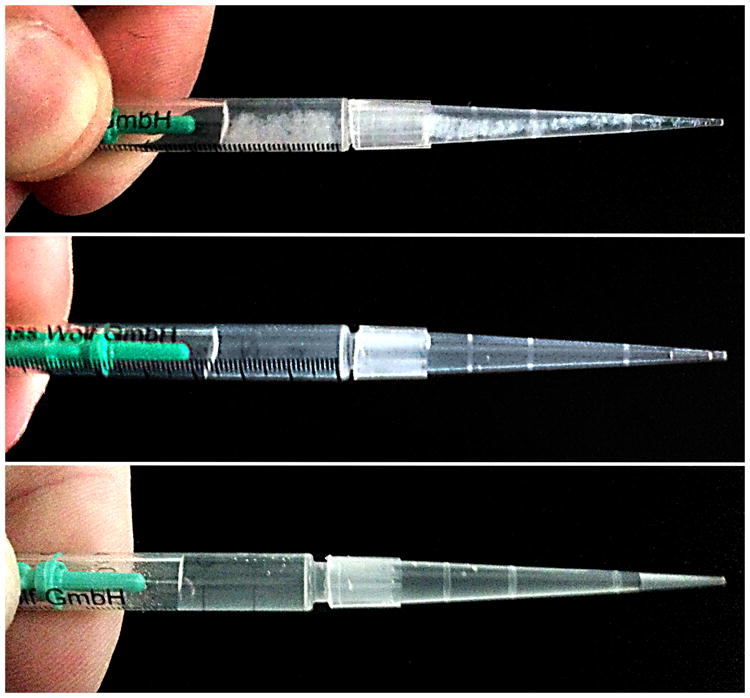

Anecdotal evidence recorded during preparation of peptide-LPS suspensions at high concentrations (700 μM peptide and 1.4 mg/mL LPS) suggest that the increase in LPS particle diameter in the presence of WLBU2 is not caused by an increase in the individual vesicle size, but rather is due to large-scale aggregation of vesicles (Fig. 7). While there was aslight increase in opalescence of LPS suspensions when PmBwas added, the large-scale aggregation observed with WLBU2-LPS did not occurin either the PmB-LPS or peptide-free LPS suspensions. No aggregation was observed in the LPS-free solutions of peptide, evenat concentrations as high as 1.4 mM.

Fig. 7.

Visible aggregation rapidly occurs in concentrated mixtures of WLBU2 and LPS (top), but not in PmB-LPS (middle) or peptide-free LPS suspensions (bottom).

Taken together, the results described above strongly support the hypothesis that peptide insertion and stabilization of intact LPS vesicles occurs in the case of WLBU2, while PmB causes peptide-induced destabilization and disruption of LPS vesicles. Taken together, the results described above strongly suggest that PmB causes peptide-induced destabilization and disruption of LPS vesicles. In contrast, WLBU2 does not appear to destabilize LPS vesicles, and may even induce aggregation of the vesicles. Moreover, they suggest that the high value of adsorbed mass for WLBU2-LPS mixtures at high peptide concentration (Fig. 4) can be attributed to location of intact WLBU2-LPS vesicles or vesicle aggregates at the interface. We are currently evaluating the feasibility of endotoxin capture using membrane-active peptides which have been covalently tethered to surfaces by short and long hydrophilic linkers, and results from that work will contribute to the subject of a future report.

Conclusions

Analysis of the interfacial behavior of mixtures of LPS and peptides using interfacial tensiometryand OWLS, evaluation of peptide structure using CD, and determination of the particle size distributions using DLS all strongly suggest that peptide insertion into intact LPS vesicles occurs without destabilization in the case of WLBU2, while PmB appears to cause peptide-induced destabilization and disruption of LPS vesicles. In the context of blood purification with hemoperfusion, the most desired outcome is insertion and tight binding of the peptide in the bacterial membrane or LPS vesicle, without destabilizing the membrane. Disruption and concomitant lysis of the membrane could cause there turn of LPS or cellular degradation products to the circulating blood, and is not desirable. Thus, we expect that presentation of WLBU2 at an interface, tethered in a fashion preserving its solvent accessibility and mobility, may promote the capture of pathogens or endotoxin that reach the surface without destabilizing or disrupting the captured vesicle or pathogen. Based on the results provided here, there is no reason to expect a similar outcome with PmB.

Research Highlights.

WLBU2 strongly binds lipopolysaccharide (LPS, endotoxin) vesicles

Polymyxin B appears to destabilize and disrupt the membrane of LPS vesicles

WLBU2 becomes α-helical and stably locates in the membrane of LPS vesicles

Hemoperfusion sorbents based on WLBU2 hold promise for treatment of sepsis

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Kerry McPhailand Dr. Jeff Nason for the use of their CD and DLS instruments, respectively. This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB, grant no. R01EB011567). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIBIB or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Wax RS. Epidemiology of sepsis: An update. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S109–S116. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002;420:885–891. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood K, Angus D. Pharmacoeconomic implications of new therapies in sepsis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22:895–906. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422140-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuno N, Ikeda T, Ikeda K, Hama K, Iwamoto H, Uchiyama M, Kozaki K, Narumi Y, Kikuchi K, Degawa H, Nagao T. Changes of cytokines in direct endotoxin adsorption treatment on postoperative multiple organ failure. Ther Apher. 2001;5:36–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-0968.2001.005001036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anspach FB. Endotoxin removal by affinity sorbents. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2001;49:665–681. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(01)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buttenschoen K, Radermacher P, Bracht H. Endotoxin elimination in sepsis: Physiology and therapeutic application. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2010;395:597–605. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0658-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies B, Cohen J. Endotoxin removal devices for the treatment of sepsis and septic shock. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2011;11:65–71. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoji H. Extracorporeal endotoxin removal for the treatment of sepsis:Endotoxin adsorption cartridge (Toraymyxin) Theor Apheresis Dial. 2003;7:108–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-0968.2003.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincent JL, Laterre PF, Cohen J, Burchardi H, Bruining H, Lerma FA, Wittebole X, De Backer D, Brett S, Marzo D, Nakamura H, John S. A pilot-controlled study of a polymyxin B-immobilized hemoperfusion cartridge in patients with severe sepsis secondary to intra-abdominal infection. Shock. 2005;23:400–405. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000159930.87737.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda T. Hemoadsorption in critical care. Ther Apher. 2002;6:189–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-0968.2002.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueno T, Sugino M, Nemoto H, Shoji H, Kakita A, Watanabe M. Effect over time of endotoxin adsorption therapy in sepsis. Theor Apheresis Dial. 2005;9:128–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1774-9987.2005.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hlady V, Buijs J. Protein adsorption on solid surfaces. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1996;7:72–77. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(96)80098-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neff JA, Tresco PA, Caldwell KD. Surface modification for controlled studies of cell–ligand interactions. Biomaterials. 1999;20:2377–2393. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onaizi SA, Leong SSJ. Tethering antimicrobial peptides: Current status and potential challenges. Biotechnol Adv. 2011;29:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anspach FB, Hilbeck O. Removal of endotoxins by affinity sorbents. J Chromatogr. 1995;711:81–92. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(95)00126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, Paterson DL. Colistin: The re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2006;6:589–601. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogardt M, Schmoldt S, Götzfried M, Adler K, Heesemann J. Pitfalls of polymyxin antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:1057–1061. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hancock REW. Cationic peptides: Effectors in innate immunity and novel antimicrobials. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2001;1:156–164. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hancock REW, Rozek A. Role of membranes in the activities of antimicrobial cationic peptides. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;206:143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gough M, Hancock R, Kelly N. Antiendotoxin activity of cationic peptide antimicrobial agents. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4922–4927. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.4922-4927.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott MG, Yan H, Hancock REW. Biological properties of structurally related a-helical cationic antimicrobial peptides. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2005–2009. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.2005-2009.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cirioni O, Giacometti A, Ghiselli R, Bergnach C, Orlando F, Silvestri C, Mocchegiani F, Licci A, Skerlavaj B, Rocchi M, Saba V, Zanetti M, Scalise G. LL-37 protects rats against lethal sepsis caused by gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1672–1679. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1672-1679.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deslouches B, Gonzalez IA, DeAlmeida D, Islam K, Steele C, Montelaro RC, Mietzner TA. De novo-derived cationic antimicrobial peptide activity in a murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:669–672. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deslouches B, Islam K, Craigo JK, Paranjape SM, Montelaro RC, Mietzner TA. Activity of the de novo engineered antimicrobial peptide WLBU2 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in human serum and whole blood: Implications for systemic applications. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3208–3216. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3208-3216.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deslouches B, Phadke SM, Lazarevic V, Cascio M, Islam K, Montelaro RC, Mietzner TA. De novo generation of cationic antimicrobial peptides: Influence of length and tryptophan substitution on antimicrobial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:316–322. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.1.316-322.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montelaro RC, Mietzner TA. U.S. Patent 6,887,847,2005 Virus derived antimicrobial peptides.

- 27.Gonzalez IA, Wong XX, De Almeida D, Yurko R, Watkins S, Islam K, Montelaro RC, El-Ghannam A, Mietzner TA. Peptides as potent antimicrobials tethered to a solid surface: Implications for medical devices. Nature Precedings. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skinner MC, Kiselev AO, Isaacs CE, Mietzner TA, Montelaro RC, Lampe MF. Evaluation of WLBU2 peptide and 3-O-octyl-sn-glycerol lipid as active ingredients for a topical microbicide formulation targeting Chlamydia trachomatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:627–636. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00635-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costa F, Carvalho IF, Montelaro RC, Gomes P, Martins MCL. Covalent immobilization of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) onto biomaterial surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:1431–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McClanahan JR, Peyyala R, Mahajan R, Montelaro RC, Novak KF, Puleo DA. Bioactivity of WLBU2 peptide antibiotic in combination with bioerodible polymer. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38:530–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryder MP, McGuire J, Schilke KF. Cleaning requirements for silica-coated sensors used in optical waveguide lightmode spectroscopy. Surf Interface Anal. 2013;45:1805–1809. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Popat KC, Johnson RW, Desai TA. Characterization of vapor deposited thin silane films on silicon substrates for biomedical microdevices. Surf Coat Technol. 2002;154:253–261. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dill JK, Auxier JA, Schilke KF, McGuire J. Quantifying nisin adsorption behavior at pendant PEO layers. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2013;395:300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lampi MC, Wu X, Schilke KF, McGuire J. Structural attributes affecting peptide entrapment in PEO brush layers. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;106:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramsden JJ. Porosity of pyrolysed sol-gel waveguides. J Mater Chem. 1994;4:1263–1265. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitmore L, Wallace BA. Dichroweb, an online server for protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W668–W673. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitmore L, Wallace BA. Protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopy: Methods and reference databases. Biopolymers. 2008;89:392–400. doi: 10.1002/bip.20853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herráez A. Biomolecules in the computer: Jmol to the rescue. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education. 2006;34:255–261. doi: 10.1002/bmb.2006.494034042644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maupetit J, Derreumaux P, Tuffery P. Pep-fold: An online resource for de novo peptide structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W498–W503. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thévenet P, Shen Y, Maupetit J, Guyon F, Derreumaux P, Tufféry P. Pep-fold: An updated de novo structure prediction server for both linear and disulfide bonded cyclic peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W288–W293. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu X, Ryder MP, McGuire J, Schilke KF. Adsorption, structural alteration and elution of peptides at pendant PEO layers. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;112:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]