1. The life cycle of the centrosome field

Centrosomes and centrioles were ‘born’ towards the end of the nineteenth century when they were first spotted and studied by astute cell and developmental biologists, including Edouard Van Beneden, as well as Theodor Boveri and Walther Fleming, who coined the terms ‘centrosome’ and ‘centriole’, respectively, that still designate these structures today. There was much initial excitement about centrosomes and centrioles, fuelled notably by their suggestive position in the cell centre, by their role during fertilization and by seminal experiments that lead to the formulation of the chromosomal theory of heredity. Daring postulates were put forth about their importance as polar corpuscle and organizers of cell division, as coordinators of karyokinesis and cytokinesis, or as drivers of malignant transformation. After this flamboyant debut, centrosomes and centrioles gradually left centre stage as the twentieth century unfolded. The advent of electron-microscopy in the 1950s revived interest in these structures, in particular when it became apparent that centrioles have a remarkable ninefold radial symmetric arrangement of microtubules that is also imparted onto cilia and flagella. However, detailed understanding of the mechanisms underlying the assembly and function of centrosomes and centrioles would have to wait several more decades.

To appreciate the uncertain state of affairs in the 1970s, one can consider the thoughtful chapter of Chandler Fulton [1, p. 170], who started his contribution with these words: ‘If one wandered about asking biologists to complete the sentence “Centrioles are…” the answers might well range from “I don't know” to “Centrioles are self-replicating organelles responsible for the synthesis and assembly of microtubules”. Although it is conceivable that the later reply contains a little truth, the “I don't know” is more likely to be the reply of an expert’.

How did we go from such uncertainty to the renaissance that this Theme Issue is heralding? The field has indeed experienced a rebirth as evidenced by comparing the few dozen articles on the centrosome published each year in the early 1980s with the over 400 contributions in the year 2013, or by considering the growing number of conferences in the field. Many novel avenues of research have been opened recently: the centrosome is back in the thinking of many cell and developmental biologists after a long eclipse during which even the term centrosome was neglected to the benefit of the acronym MTOC: Microtubule Organizing Centre.

2. A timely collective coverage

The centrosome thus represents an extremely timely topic for a collective coverage. After The centrosome in 1992 [2], The centrosome in cell replication and early development in 2000 [3] and Centrosomes in development and disease in 2004 [4], it seemed appropriate to assemble a novel collection of papers on the centrosome. This is why, in spite of the many excellent reviews published in recent years, we have accepted the invitation from the Commissioning Editor of the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B to assemble this Theme Issue entitled ‘The centrosome renaissance’.

Because such Theme Issues are restricted to a limited number of contributions, a focus needed to be given. We chose this focus to be the centrosome in animal cells, while including some information from other systems, including budding yeast and unicellular organisms. Regrettably, however, other important aspects of the field had to be neglected given the space constraints. We asked the authors not only to cover recent findings, but also to provide their views on the issues at stake and emphasize important questions for the future. We articulated the 16 contributions into four thematic groups: centrosomes in history and evolution, centrosome assembly and structure, the functions of centrosomes, as well as centrosomes in development and diseases. In addition, the present piece serves as a preface, whereas an exceptional account by Ulrich Scheer on Boveri's years in Würzburg, with newly discovered plates of his work, follows as a prologue and as a reminder of the origin of a field started over a century ago [5].

In order to have a Theme Issue that is representative of the main advances and concepts in the field, each contribution has been reviewed by two or three experts who could have written just as well on the particular topic they have been asked to review. Those reviewers who were willing to have their names disclosed are listed at the end of this preface. In this manner, in addition to the two undersigned who acted as joint editors for every chapter, the contents of this Theme Issue reflect the direct or indirect input of some 50 leading scientists in the field, whom we wish to thank wholeheartedly for their important contributions.

3. The main characters

In this preface, we attempt to set the stage for the Theme Issue, while avoiding redundancies with the individual contributions to the extent possible, such that the reader is invited to consult the respective papers for further information and references.

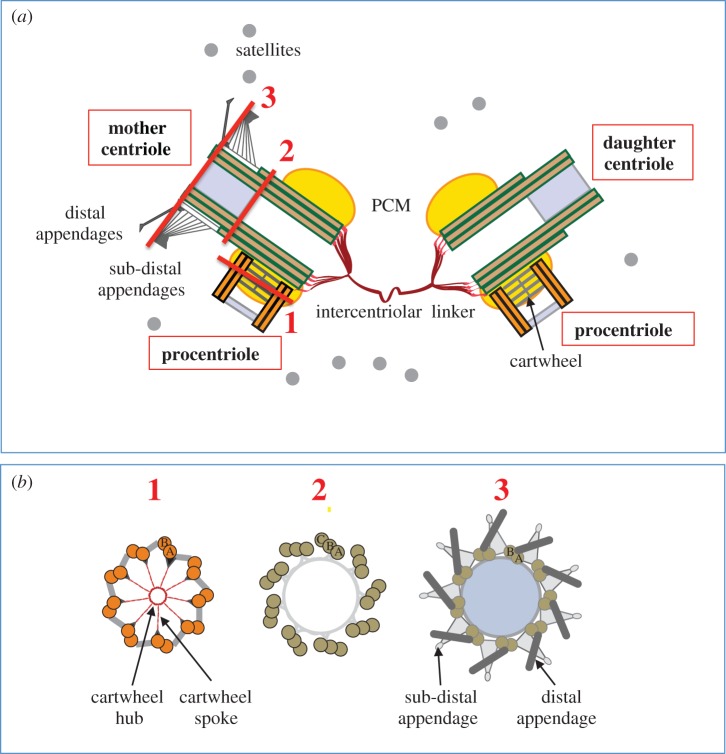

As in all fields, but especially in ones that span more than a century, during which conceptual frameworks and experimental approaches have changed substantially, there is a need to ensure some shared basic terminology to facilitate communication between members of the community and accelerate entry into the field for newcomers. For instance, until when should a procentriole be referred as such before being called a centriole in the canonical centrosome duplication cycle? Hereafter, we use the term procentriole to refer to a centriolar cylinder from the moment it is discernible next to the proximal end of a parental centriole, approximately at the G1/S transition, until mitosis of that cell cycle (figure 1a). During this time interval, a procentriole and the parental centriole next to which it emerges are referred to collectively as a diplosome. After disengagement of the procentriole from the parental centriole during mitosis and subsequent entry into G1, the younger structure, which used to be the procentriole, is now referred to as the daughter centriole, and the older one as the mother centriole (figure 1a). The mother centriole harbours distal and sub-distal appendages whose distribution mirrors the ninefold symmetry of the centriole, and which are acquired at the end of the cell cycle following that in which the procentriole emerged. The distal appendages mediate docking of the mother centriole to the plasma membrane in cells that exit the cell cycle. Once docked in that location, the mother centriole is referred to as the basal body, and by some workers as the kinetosome [7], and serves to template formation of the axoneme in cilia and flagella. Note that nowadays the basal body is frequently referred to as a centriole, both for simplicity and because basal bodies and centrioles can interconvert in many cell types. Note also that often, including in the present piece, the plural ‘centrioles’ is used to refer indiscriminately to all centriolar cylinders (i.e. jointly to centrioles and procentrioles).

Figure 1.

Centrosomes in human cells. (a) Representation of a pair of centrosomes in human cells viewed from the side during the S phase of the cell cycle. The lines designated 1, 2 and 3 indicate the positions corresponding to the cross sections shown in (b). The parental centrioles are approximately 450 nm long and approximately 250 nm in outer diameter. The grey region in the distal part represents the filled lumen in the region where centrin concentrates [6]. Note that for simplicity the cartwheel is represented with only four slices and that it is present only in the procentriole in human cells. Similarly for simplicity, the PCM/centrosomal matrix is represented solely around the proximal region, even though it is also present to a lesser extent around the more distal segments. (b) Corresponding cross sections, viewed from the proximal end, in regions 1 (proximal part of the centriole, with cartwheel highlighted and triplet microtubules denoted A, B, C), 2 (central part of the mother centriole, also with triplet microtubules) and 3 (distal part of the mother centriole, with double microtubules denoted A, B). (Online version in colour.)

Apart from centrioles, another main character in the plot is the pericentriolar material (PCM), also known as the centrosomal matrix, an electron-dense region that surrounds the centriolar cylinders, particularly their proximal part, and together with them constitutes the centrosome (figure 1a). It is now clear that centrioles and PCM are intimately linked to fulfil the numerous functions of the centrosome. However, when the centrosome was equated to an MTOC—when microtubule nucleation was the main function envisaged for the entire organelle—the dominant view was that centrioles were not important for centrosome function. That centrioles are instrumental in maintaining centrosome integrity was demonstrated in human cells by injection of monoclonal antibodies against polyglutamylated tubulin, a post-translational modification of α- and β-tubulin particularly prevalent in centrioles [8]; see §5). This led to centriole loss and subsequent dissolution of the entire centrosome. In Caenorhabditis elegans, partial depletion of centriolar components by RNAi results in smaller centrioles that recruit less PCM than in the wild-type, further indicating that PCM-size scales with centriolar material [9,10] . Therefore, centrioles play a fundamental role in assembling the centrosome organelle.

There are other cast members that are neither centriolar nor PCM components, yet clearly important for the overall architecture of the centrosome (figure 1a). These include the inter-centriolar linker that connects the mother centriole and the daughter centriole in G1, as well as the two diplosomes thereafter, as well as centriolar satellites, granules approximately 100 nm in diameter that remain incompletely described with respect to their composition and function, apart from being important for primary cilium assembly [11,12].

Besides knowing the cast of characters, it is also important to ensure that the nomenclature of the molecular players that participate in the play is accessible to a broad base of scientists. Too many proteins have been referred to under more than one name. For instance, the human protein related to C. elegans SAS-4 (Spindle ASsembly abnormal 4) has been referred to as SAS4 (to indicate its relatedness with the worm protein), as CPAP (for Centrosomal P4.1-Associated Protein, as it was first named, before the relationship to SAS-4 was known) or CENPJ (for Centromere Protein J, for reasons that remain unclear). Although this naming plethora is not an issue specific to the centrosome field, a concerted effort would be welcome to clarify the language.

We hope that the reader of this Theme Issue will be in a position to appreciate the fact that despite considerable progress in understanding the molecular composition, the assembly mechanisms and the numerous functions of centrosomes, many fascinating questions remain open. The field is at an exciting juncture: as many of the molecular mechanisms are being unravelled, the time is ripe for addressing some of the important long-standing questions, including ones that first emerged when this remarkable organelle was discovered over a century ago. We discuss below some of these questions, referring the reader to chapters of this Theme Issue for further information when appropriate.

4. On the origin and evolution of the centrosome

Some of the most pressing questions should probably be posed from an evolutionary perspective: given that the centrosome is not present in all multicellular organisms, nor in all cells of a given organism, one must ask what this organelle adds to the cell economy that explains its presence as well as its specialization in different biological systems. It is now well recognized that the centrosome evolved from an ancestral basal body/flagellum [13]. Whatever the actual scenario for the origin of the centrosome organelle in the Amorphea lineage (see chapter by Juliette Azimzadeh) [14], it is interesting to consider what consequences the many variations in centrosome structure and composition observed in extant eukaryotes may have on centrosome function. For instance, what are the functional consequences associated with the fact that many of the genes encoding centrosomal components present in unicellular organisms and in vertebrate species are missing in Drosophila or in C. elegans?

5. On centriolar microtubules

The microtubules that make up the walls of centrioles have a unique organization, unlike that of any other microtubule in the cell, except for the ones of the axoneme that they template. In particular, centriolar microtubules have a very slow turnover and are resistant to microtubule-destabilizing drugs or cold treatment [15]. Furthermore, centriolar microtubules can apparently resist the mitotic state that dramatically increases the turnover of cytoplasmic microtubules [16]. These properties are exhibited both by microtubule triplets (A, B and C microtubules) present in the proximal part of centrioles and microtubule doublets (A and B microtubules) found in the distal part of centrioles as well as in axonemes (figure 1a,b). Moreover, triplet microtubules, but not doublet microtubules, resist treatments with high temperature or high pressure [17]. Perhaps the exceptional stability of triplet microtubules stems from the short distance between the A microtubule of one triplet and the C microtubule of the adjacent triplet, which could provide additional mechanical strength. Moreover, triplet microtubules could provide different surface properties from that of doublets to associate with specific PCM proteins.

The mechanisms underlying the exceptional stability of centriolar microtubules are not sufficiently understood, but they are accompanied by the extensive post-translational modifications of tubulin subunits, including polyglutamylation, detyrosination, acetylation and polyglycylation [18]. These modifications are thought to be important for centriole integrity, as evidenced by the antibody injection experiments described above. By analogy to the impact of post-translational modifications on the binding of microtubule-associated proteins or motors on neuronal microtubules [18], one possibility is that such modifications promote the association of PCM proteins with centriolar microtubules, which in turn could contribute to centriole stability. Such reciprocal stabilization of the two compartments would increase over time, resulting in the accumulation of post-translational modifications, which are thus candidate biomarkers of centriole age. Another question in the realm of centriolar microtubules that deserves further investigation concerns the rare δ- and ε-tubulin, which are required, respectively, for the addition of C or B plus C microtubules [19–22]. What exactly do these tubulin variants bring to centrioles in those species that have them and how can they be dispensable in other species?

6. On centriole architecture

The structural complexity of the centriole is simply amazing, from the intricate cartwheel present within the procentriole at the onset of the assembly process to the elaborate appendages of the mother centriole added at the end of it (see article by Mark Winey and Eileen O'Toole) [23]. A central question in the field has been to unravel the mechanisms governing the near universal ninefold symmetry of this intricate biological edifice. The discovery that proteins of the SAS-6 family can self-assemble into ring-like structures from which emanate nine spokes that resemble a slice of the cartwheel provides an organizing principle at the root of such symmetry [24,25] (figure 1b; see article by Masafumi Hirono [26]). Because the nine spokes in these structures correspond to the coiled-coil domain of SAS-6 proteins, this model suggests that the length of this domain may determine the diameter of the centriole, although whether this is the case remains to be tested.

An interesting question pertains to how length of the centriole is controlled. The procentriole reaches a length approximately 80% of that of the parental centriole by the time of mitosis, with the remaining elongation taking place in the subsequent cell cycle [27,28]. How is centriole length precisely regulated? In human cells and in Drosophila, POC1 proteins are important for such regulation, since their depletion causes shorter centrioles while their overexpression results in overly long centrioles [29,30]. In human cells, overexpression of CPAP also leads to overly long centrioles, as does depletion of CP110, a protein which normally caps the very distal end of centrioles [31–33]. Although uncovering these components is an important step forward, the underlying mechanisms remain sketchy.

Is centriole length set by the extent of microtubule polymerization? What components, if any, regulate the polymerization of centriolar microtubules is not known. Given that the centriole is approximately 450 nm long in human cells, and that the polymerization rate of interphasic cytoplasmic microtubules is approximately 10 μm min−1 [16], it should take only a few seconds for microtubules exhibiting regular dynamics to reach this length. And yet procentriolar elongation takes hours in proliferating somatic cells [27]. Perhaps some of the centriolar proteins that bind tubulin dimers or microtubules, such as CPAP or Cep135 in human cells [34,35], can modulate polymerization dynamics in a manner that differs substantially from that of conventional microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs). Alternatively, perhaps negative regulation of conventional MAPs, which would lead them to function less efficiently than usual, takes place during centriole assembly. Clearly, the analysis of centriolar microtubules and their regulation is an exciting frontier of research. Centriole elongation also involves the assembly of an intra-luminal structure in the distal end (figure 1). Except for the presence of Centrin proteins and the Centrin-binding protein POC5, which is required for the assembly of the distal part of centrioles [36], little is known about the molecular composition of this intra-luminal structure or about its interaction with the centriole wall. This interaction could, however, participate in maintaining the cohesion of the centriole and controlling its diameter [37].

Increased understanding of questions related to centriole architecture offers the exciting prospect of obtaining molecular handles to tinker with the underlying principles so as to probe their biological significance: what would be the consequences of having a procentriole that has the wrong diameter or is too short? A thorough understanding of the system might even enable one to engineer centrioles at will. Synthetic centrioles are on the horizon.

7. On pericentriolar material organization

How centrioles can help organize the PCM is not yet clear, but perhaps the exceptional stability of centriolar microtubules provides a favourable milieu for recruiting γ-tubulin-containing nucleation complexes. Recent results obtained by super-resolution microscopy indicate that the PCM is organized in a stereotyped manner around the centriole [38,39], in line with the notion that the latter organizes the former. However, the influence may be bidirectional here as well. Perhaps the organized network of PCM proteins surrounding the proximal part of the parental centriole is key in ensuring that the procentriole forms orthogonal to it. There is a land of discovery ahead regarding the mechanisms mediating interaction between centrioles and PCM, as exemplified by work with the Drosophila PCM protein Cnn [40]: what are the association kinetics of proteins that bridge the external wall of centrioles with the innermost part of the PCM and have properties that allow them to transform the order inherent to centrioles into ordered assembly of the surrounding PCM? More generally, what physico-chemical properties explain why the PCM excludes ribosomes, for example, and allow the concentration of many specific proteins and activities? More generally, how is the boundary of the PCM controlled (see article by Tony Hyman and collaborators) [41]? During the cleavage divisions of early embryos, part of the answer is cell size, as was evident from the days of Boveri and established quantitatively more recently in C. elegans [42].

How does the PCM interact with the two sets of appendages associated with the mother centriole? Insights into this question could come from analysing how appendages attach to the centriole during mitotic exit. Analysis by electron microscopy established that centrosome organization is modified during mitosis, with the PCM forming a perfect halo around each parental centriole and the appendages transiently disappearing from the mother centriole before reforming on both parental centrioles [43–45]. This is also the moment when the former daughter centriole reaches its full length and thus completes the centriole maturation process. Investigations of centrosome remodelling during mitosis promises to yield interesting insights about the completion of centriole biogenesis, which may be coupled to the disengagement step and the priming of centriole duplication that take place at this moment.

8. On centrosome duplication: from yeast to man

To what extent are the mechanisms of centrosome duplication conserved across evolution? Historically, two ideas were most prevalent to explain the apparent self-reproduction of the centrosome: first, a crystallization-based mechanism, with the local concentration of a given component acting as a nucleating agent; second, a nucleic acid-based mechanism, whereby an analogous principle to that governing replication of the genetic material would hold for duplicating the centrosome. Whereas there is currently no solid evidence in favour of the second proposal, the local oligomerization of SAS-6 proteins at the site of cartwheel assembly supports the first idea. The duplication of the spindle pole body (SPB) in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae also relies in part on the first mechanism, with Spc42p forming a two-dimensional crystal at the core of the satellite that will form the new SPB [46]. However, Spc42 crystallization does not occur at the very onset of the duplication process. Instead, the most initial step entails duplication of the so-called half-bridge according to a remarkably simple molecular mechanism of mirror-image assembly (see article by John Kilmartin) [47]. Is this principle evolutionarily conserved, perhaps representing the core of an ancient mechanism that is present but not yet appreciated in the context of centriole duplication? Conceivably, the two major components of the SPB half-bridge, Cdc31p and Sfi1p, which are the only SPB components present in S. cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe and vertebrates, may participate in a similar mechanism in metazoans. If so, where should one look for the presence of this mechanism in animal centrosomes. Perhaps in the connection between the nucleus and the centrosome, which is ensured by the half-bridge in S. cerevisiae; or else in the link between the centriole and the procentriole, by analogy with the relationship between the half-bridge and the SPB. An electron-dense structure connecting the proximal end of the parental centriole with the nascent procentriole has been observed in human cell [48], but neither the Cd31p-related protein Centrin3 nor the Sfi1p homologue hSfi1 seem to be enriched at that location.

If not Centrin3 or hSfi1, what else may initiate the process of procentriolar formation in animal cells? Intriguingly, the onset of formation is preceded by a change in the distribution of the Plk4 kinase from being uniformly distributed around the proximal part of the parental centriole to being concentrated on a single site: this transition may represent a critical symmetry breaking event [38] (also see articles by Kip Sluder [49], as well as by Elif Firat-Karalar and Tim Stearns [50]). Does such Plk4 concentration occur next to a specific triplet microtubule? Rotational asymmetries do exist around basal bodies, as evidenced by the stereotypical distribution of rootlets and other structures associate with basal bodies in flagellates and ciliates [51]. Does this occur because each triplet microtubule is unique in some way, or does this stereotyped distribution reflect asymmetries inherent in the cytoskeletal elements that are connected to the basal bodies?

Regardless of whether the local concentration of Plk4 initiates procentriole formation, it is important to note that the current body of evidence speaks against the notion of ‘templating’ in the strict sense of the term for centriole duplication. Indeed, there is currently no evidence for the copying of a putative mould, be it made of nucleic acids or proteins, and which would be present in the parental centriole to then serve as a blueprint for procentriole assembly. Therefore, the term ‘templated formation’ that has been used often to describe the process by which a procentriole is seeded next to a parental centriole in proliferating cells does not seem appropriate. Instead, we suggest using the more neutral term of ‘centriole-guided’ procentriole formation. Whatever the term eventually adopted by the community, it is necessary to distinguish the templated formation of ciliary and flagellar axonemes from the basal body from such centriole-guided formation of procentrioles.

9. On the connection with the nucleus

Not only does the centrosome reproduce during the cell cycle, but so also do cellular constituents that are associated with it. Indeed, the centrosome is not free within the cytoplasm, but instead is anchored to other compartments, particularly the nucleus. This connection is essential for the migration of nuclei in large eggs or in the fly syncytial embryo, as well as for overall cell polarity. The flagellar apparatus is also connected to the nucleus in most unicellular organisms, with rare exceptions such as kinetoplastids where the basal boy is connected to the kinetoplast [52]. Importantly, the connections that anchor centrosomes have to be reproduced along with the centrosome itself in order to retain them in the two daughter cells. This renders the complete reproduction of the centrosome a topologically complex process. The positioning of centrosomes at the cell centre depends on the dynamics of microtubules that are anchored primarily on the mother centriole, whereas the daughter centriole alone cannot remain at the cell centre [53]. However, upon depolymerization of cytoplasmic microtubules, the drift of the mother centriole from the central position of the cell is minimal [53], indicating that other connections contribute to proper positioning. Perhaps distal appendages play a role in anchoring the mother centriole to another network such as the actin cytoskeleton.

Could the need to maintain connections with other compartments explain the striking conservation of ancestral centrin genes, whose products are concentrated in the distal lumen of centrioles and accumulate early during procentriole formation (figure 1a)? Centrin was discovered in two green algae as the major component of calcium-dependent contractile striated flagellar roots connecting the basal bodies to the nucleus, the so-called Nucleus Basal Body Connector (NBBC) [54,55]. Calcium treatment causes shortening of the connector fibres [55]. In C. reinhardtii, this connector forms a sort of perinuclear basket, and mutation of the centrin gene results in defective connection between the basal bodies and the nucleus, as well as variable flagella number, indicating that the NBBC is instrumental in coordinating the segregation of basal bodies and nucleus [56].

The C. reinhardtii centrin gene defines a sub-family of centrin genes (CEN2), the presence of which always correlates with that of a basal body/axoneme motile apparatus, being for example absent in plants, higher fungi such as yeasts, or animals like C. elegans [13]. Accordingly, loss of centrin2 alters primary ciliogenesis and promotes abnormalities related to ciliopathies in zebrafish embryos [57]. Another centrin gene, discovered as a Cell Division Cycle gene (CDC31) in the yeast S. cerevisiae, is required for SPB duplication and cannot be complemented by centrin2 genes, thus defining another conserved centrin sub-family (CEN3) [58]. Present in fungi and most animals, but absent in plants, the CEN3 subfamily apparently co-evolved with the presence of centrosomes or SPBs, with the notable exception of flies and worms [13]. The CEN3 subfamily could participate in the connection between the nucleus and the centrosome/SPB in some species, as it does in S. cerevisiae, whereas Ecdysozoa such as flies and worms would have evolved a different type of connection in which CEN3 is dispensable. Of note, whereas Cen3p is more concentrated in the centrosome of vertebrate cells [58], Cen2p is most abundant in the nucleus and the cytoplasm [6] and participates also in the nucleotide excision repair reaction [59]. Intriguingly, nucleotide excision repair after UV-irradiation is the only known function that is impaired upon knocking out all centrin genes in DT40 chicken lymphoma B cells [60]. However, this function does not require the calcium-binding capacity of Cen2p, whereas its recruitment to the centrosome and its binding to the centrosomal centrin-binding POC5 does [6,61]. The centrosomal calcium-dependent functions may be complemented in this cell line by other members of the Calmodulin superfamily.

10. On the centrosome as signalling centre

An appealing and relatively recent role ascribed to the centrosome is one in the integration and coordination of signalling pathways (see article by Erich Nigg and collaborators) [62], which had been suggested by the analogous and more established role of the yeast SPB. Many aspects, including long suspected links between centrosomes and DNA damage response pathways, have begun to be unravelled and will likely be deciphered further in the years to come. Could there even be something in common between the centrosome as a signalling centre and the cilium being used in major signalling transduction cascades (see article by Maxence Nachury) [63]? The molecular and functional similarities between cilia and immune synapses in which centrosome repositioning at the plasma membrane is critical (see article by Jane Stinchcombe and Gillian Griffith) [64] further lends support to the notion that the centrosome functions as a signalling hub in many biological contexts.

The centrosome may also act as a signalling centre in a setting where it is usually perceived as a mere source of microtubules. The ability of centrosomes to propel the associated male pronucleus towards the centre of large marine or amphibian eggs in a matter of minutes fascinated the early students of fertilization and development. How can centrosomes and the microtubules they nucleate sense egg size and shape to reach the cell centre in due time to be coordinated with mitotic entry? Microtubules possess an autonomous ability to reach the geometric centre of a given volume [65], but in vivo biochemical waves emanating from centrosomes are important also to set the timing of cell division (see article by Tim Mitchison and collaborators) [66]. The idea that centrosomes can set gradients of enzymatic activities is not new, but the field is at a stage where these ideas can be modelled and tested with the appropriate experimental approaches. The fact that the Golgi apparatus can also act as an MTOC in vertebrate cells (see article by Rosa Rios) [67] adds another layer of complexity to this topic in offering yet another potential source of signalling.

11. On the mother–daughter asymmetry

It is now well established that the conservative duplication of centrioles and of the yeast SPBs, resulting in an old and a new unit, contributes to asymmetric cell division and stemness (see article by Jose Reina and Tano Gonzalez) [68]. But why should there be two centrioles per centrosome instead of one, as is the case in the yeast SPB? In animal cells, the capacity of the daughter centriole to nucleate microtubules and to guide procentriole assembly occurs well before microtubules are anchored on sub-distal appendages of the mother centriole to form an aster or permit docking at the plasma membrane via distal appendages to take place to grow a primary cilium. One possible benefit of such a time delay could be to introduce considerable flexibility into the design of the centrosome organelle. In this way, both free and anchored microtubules can be produced independently, considering that the inter-centriolar distance can reach 20 μm in some cells [69]. Regulating this distance could be part of differentiation programmes that set where microtubules are operating in a given cell and thus contribute to facilitate tissue organogenesis or response to extracellular cues. Having such a time delay between the biogenesis of the two units imposes a slow differentiation process, with the distinct control of centriole length as well as the timely control of disengagement of the two centrioles at mitotic exit, after the two diplosomes have separated at the G2/M transition (see the article by Elmar Schiebel and collaborators) [70].

12. On centrosome and disease

The links between centrosomes and disease are as old as the field itself, with Boveri's first observations with polyspermic eggs that lead to multipolar divisions and aneuploidy, and it has taken over a century to clarify some of the tenets of this connection. Whereas it now appears clear that centrosome dysfunctions can favour tumour onset (see article by Susana Godinho and David Pellman) [71], it will be important to figure out in each type of tumour whether this is by promoting aneuploidy, as Boveri postulated, by promoting tissue destabilization and invasion, through cell polarity defects or perhaps a combination of these effects. Other diseases associated with centrosome dysfunctions have a more recent history but nonetheless an important impact on human health. Among these diseases, it will be important to address, for example, why the brain can be exclusively affected by some mutations in centrosomal components that lead to microcephaly, whereas other tissues are seemingly spared (see article by Fanni Gergely and collaborators) [72].

13. On removing centrioles

Although usually very stable, centrioles probably have a finite lifetime in most cells and disappear in a stereotyped manner in specific cell types. This is the case during oogenesis in most metazoan organisms, and such disappearance is critical to ensure that the newly fertilized embryo is endowed with a single pair of centrioles, which is delivered by the sperm [73]. Centriole loss can also take place in somatic cells, as for example during mammalian skeletal myogenesis, when myoblasts fuse into myotubes [74]. Whether there is a common mechanism in both cases is not known, nor is it known whether such disappearance recapitulates in reverse the sequence of events occurring during centriole assembly. Could there be a common theme between these two cell types that explains why they both lose their centrosome?

14. Concluding remarks

One may wonder why the centrosome has ever evolved in metazoans if other multicellular organisms such as higher plants live perfectly well without them. And one may further wonder why some differentiated animal cells that no longer divide, like neurons or leucocytes, retain a centrosome while others such as myotubes eliminate centrosomes? Likewise, why do some resting cells grow a primary cilium whereas others never do, despite having the appendages on the mother centriole that could enable them to do so? Can we propose a unified functional framework in which all these differences would make sense? Cell polarity and its transmission to daughter cells through division in somatic lineages, or from the male gamete to the zygote through fertilization in most animal species, come across as a broad unifying theme that encompasses the numerous functions in which the centrosome can be involved.

In closing, let us reiterate that one cannot hope to get at a comprehensive understanding of centrosome function in diverse systems without a comparative analysis of the cellular economy resulting from the survival strategy of each organism. This is what makes the study of centrosomes both important and attractive. We trust that this Theme Issue will both provide a snapshot of the progress to date and fuel advances for the years to come. Hopefully, the next collective coverage will have answers for many of the questions that are open in 2014 and undoubtedly come up with new ones!

Acknowledgements

We thank members of our laboratories and colleagues around the world for interesting discussions over the years. We are grateful also to Fernando R. Balestra and Paul Guichard for useful comments on the manuscript and help in preparing the figure. We wish to thank the following people who acted as referees on the papers within this issue: Miguel Angel Alonso, Kathryn Anderson, Renata Basto, Mónica Bettencourt-Dias, Trisha Davis, Stefan Duensing, Susan Dutcher, Andrew Fry, Joseph Gall, David Glover, Keith Gull, Edward Hinchcliffe, Andrew Jackson, Alexey Khodjakov, Akatsuki Kimura, Michael Knop, Ryoko Kuriyama, James Maller, Thomas Mayer, Andrea McClatchey, Nicolas Minc, Ciaran Morrison, Kevin O'Connell, Judith Paridaen, Chad Pearson, Laurence Pelletier, Franck Perez, Claude Prigent, Jordan Raff, Gregory Rogers, Jeffrey Salisbury, Songhai Shi, Yukiko Yamashita and Manuela Zaccolo.

Funding statement

M.B. is supported by CNRS and Institut Curie. Work on centrosome duplication in the laboratory of P.G. is supported by a grant from the ERC (AdG 340227).

References

- 1.Fulton C. 1971. Centrioles. In Origin and continuity of cell organelles, vol. 2 (eds Reinert J, Ursprung H.), pp. 170–221. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalnins V. 1992. The centrosome. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palazzo R, Schatten GP. 2000. The centrosome in cell replication and early development, vol. 49 San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nigg E. 2004. Centrosomes in development and disease. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheer U. 2014. Historical roots of centrosome research: discovery of Boveri's microscope slides in Würzburg. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130469 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0469) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paoletti A, Moudjou M, Paintrand M, Salisbury JL, Bornens M. 1996. Most of centrin in animal cells is not centrosome-associated and centrosomal centrin is confined to the distal lumen of centrioles. J. Cell Sci. 109, 3089–3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lwoff A. 1950. Problems of morphogenesis in ciliates: the kinetosomes in development, reproduction and evolution. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bobinnec Y, Khodjakov A, Mir LM, Rieder CL, Edde B, Bornens M. 1998. Centriole disassembly in vivo and its effect on centrosome structure and function in vertebrate cells. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1575–1589. ( 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1575) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkham M, Müller-Reichert T, Oegema K, Grill S, Hyman AA. 2003. SAS-4 is a C. elegans centriolar protein that controls centrosome size. Cell 112, 575–587. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00117-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delattre M, Leidel S, Wani K, Baumer K, Bamat J, Schnabel H, Feichtinger R, Schnabel R, Gönczy P. 2004. Centriolar SAS-5 is required for centrosome duplication in C. elegans. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 656–664. ( 10.1038/ncb1146) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JY, Stearns T. 2013. FOP is a centriolar satellite protein involved in ciliogenesis. PLoS ONE 8, e58589 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0058589) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sillibourne JE, Hurbain I, Grand-Perret T, Goud B, Tran P, Bornens M. 2013. Primary ciliogenesis requires the distal appendage component Cep123. Biol. Open 2, 535–545. ( 10.1242/bio.20134457) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bornens M, Azimzadeh J. 2007. Origin and evolution of the centrosome. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 607, 119–129. ( 10.1007/978-0-387-74021-8_10) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azimzadeh J. 2014. Exploring the evolutionary history of centrosomes. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130453 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0453) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kochanski RS, Borisy GG. 1990. Mode of centriole duplication and distribution. J. Cell Biol. 110, 1599–1605. ( 10.1083/jcb.110.5.1599) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belmont LD, Hyman AA, Sawin KE, Mitchison TJ. 1990. Real-time visualization of cell cycle-dependent changes in microtubule dynamics in cytoplasmic extracts. Cell 62, 579–589. ( 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90022-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rousselet A, Euteneuer U, Bordes N, Ruiz T, Hui Bon Hua G, Bornens M. 2001. Structural and functional effects of hydrostatic pressure on centrosomes from vertebrate cells. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 48, 262–276. ( 10.1002/cm.1014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janke C, Bulinski JC. 2011. Post-translational regulation of the microtubule cytoskeleton: mechanisms and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 773–786. ( 10.1038/nrm3227) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutcher SK, Trabuco EC. 1998. The UNI3 gene is required for assembly of basal bodies of Chlamydomonas and encodes delta-tubulin, a new member of the tubulin superfamily. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 1293–1308. ( 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1293) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutcher SK, Morrissette NS, Preble AM, Rackley C, Stanga J. 2002. Epsilon-tubulin is an essential component of the centriole. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3859–3869. ( 10.1091/mbc.E02-04-0205) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dupuis-Williams P, Fleury-Aubusson A, de Loubresse NG, Geoffroy H, Vayssie L, Galvani A, Espigat A, Rossier J. 2002. Functional role of epsilon-tubulin in the assembly of the centriolar microtubule scaffold. J. Cell Biol. 158, 1183–1193. ( 10.1083/jcb.200205028) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garreau de Loubresse N, Ruiz F, Beisson J, Klotz C. 2001. Role of delta-tubulin and the C-tubule in assembly of Paramecium basal bodies. BMC Cell Biol. 2, 4 ( 10.1186/1471-2121-2-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winey M, O'Toole E. 2014. Centriole structure. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130457 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0457) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Breugel M, et al. 2011. Structures of SAS-6 suggest its organization in centrioles. Science 331, 1196–1199. ( 10.1126/science.1199325) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitagawa D, et al. 2011. Structural basis of the 9-fold symmetry of centrioles. Cell 144, 364–375. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirono M. 2014. Cartwheel assembly. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130458 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0458) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuriyama R, Borisy GG. 1981. Centriole cycle in Chinese hamster ovary cells as determined by whole-mount electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 91, 814–821. ( 10.1083/jcb.91.3.814) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chrétien D, Buendia B, Fuller SD, Karsenti E. 1997. Reconstruction of the centrosome cycle from cryoelectron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 120, 117–133. ( 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3928) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller LC, Geimer S, Romijn E, Yates J, III, Zamora I, Marshall WF. 2009. Molecular architecture of the centriole proteome: the conserved WD40 domain protein POC1 is required for centriole duplication and length control. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1150–1166. ( 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0619) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blachon S, Cai X, Roberts KA, Yang K, Polyanovsky A, Church A, Avidor-Reiss T. 2009. A proximal centriole-like structure is present in Drosophila spermatids and can serve as a model to study centriole duplication. Genetics 182, 133–144. ( 10.1534/genetics.109.101709) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohlmaier G, Loncarek J, Meng X, McEwen BF, Mogensen MM, Spektor A, Dynlacht BD, Khodjakov A, Gönczy P. 2009. Overly long centrioles and defective cell division upon excess of the SAS-4-related protein CPAP. Curr. Biol. 19, 1012–1018. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang CJ, Fu RH, Wu KS, Hsu WB, Tang TK. 2009. CPAP is a cell-cycle regulated protein that controls centriole length. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 825–831. ( 10.1038/ncb1889) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt TI, Kleylein-Sohn J, Westendorf J, Le Clech M, Lavoie SB, Stierhof YD, Nigg EA. 2009. Control of centriole length by CPAP and CP110. Curr. Biol. 19, 1005–1011. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hung LY, Chen HL, Chang CW, Li BR, Tang TK. 2004. Identification of a novel microtubule-destabilizing motif in CPAP that binds to tubulin heterodimers and inhibits microtubule assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2697–2706. ( 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0121) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carvalho-Santos Z, et al. 2012. BLD10/CEP135 is a microtubule-associated protein that controls the formation of the flagellum central microtubule pair. Dev. Cell 23, 412–424. ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.06.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azimzadeh J, Hergert P, Delouvee A, Euteneuer U, Formstecher E, Khodjakov A, Bornens M. 2009. hPOC5 is a centrin-binding protein required for assembly of full-length centrioles. J. Cell Biol. 185, 101–114. ( 10.1083/jcb.200808082) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paintrand M, Moudjou M, Delacroix H, Bornens M. 1992. Centrosome organization and centriole architecture: their sensitivity to divalent cations. J. Struct. Biol. 108, 107–128. ( 10.1016/1047-8477(92)90011-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sonnen KF, Schermelleh L, Leonhardt H, Nigg EA. 2012. 3D-structured illumination microscopy provides novel insight into architecture of human centrosomes. Biol. Open 1, 965–976. ( 10.1242/bio.20122337) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawo S, Hasegan M, Gupta GD, Pelletier L. 2012. Subdiffraction imaging of centrosomes reveals higher-order organizational features of pericentriolar material. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 1148–1158. ( 10.1038/ncb2591) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conduit PT, Brunk K, Dobbelaere J, Dix CI, Lucas EP, Raff JW. 2010. Centrioles regulate centrosome size by controlling the rate of Cnn incorporation into the PCM. Curr. Biol. 20, 2178–2186. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woodruff JB, Wueseke O, Hyman AA. 2014. Pericentriolar material structure and dynamics. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130459 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0459) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Decker M, Jaensch S, Pozniakovsky A, Zinke A, O'Connell KF, Zachariae W, Myers E, Hyman AA. 2011. Limiting amounts of centrosome material set centrosome size in C. elegans embryos. Curr. Biol. 21, 1259–1267. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robbins E, Gonatas NK. 1964. The ultrastructure of a mammalian cell during the mitotic cell cycle. J. Cell Biol. 21, 429–463. ( 10.1083/jcb.21.3.429) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vorobjev IA, Chentsov YS. 1982. Centrioles in the cell cycle. I. Epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 98, 938–949. ( 10.1083/jcb.93.3.938) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rieder CL, Borisy GG. 1982. The centrosome cycle in PtK2 cells: asymmetric distribution and structural changes in the pericentriolar material. Biol. Cell 4. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bullitt E, Rout MP, Kilmartin JV, Akey CW. 1997. The yeast spindle pole body is assembled around a central crystal of Spc42p. Cell 89, 1077–1086. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80295-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kilmartin JV. 2014. Lessons from yeast: the spindle pole body and the centrosome. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130456 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0456) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guichard P, Chretien D, Marco S, Tassin AM. 2010. Procentriole assembly revealed by cryo-electron tomography. EMBO J. 29, 1565–1572. ( 10.1038/emboj.2010.45) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sluder G. 2014. One to only two: a short history of the centrosome and its duplication. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130455 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0455) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fırat-Karalar EN, Stearns T. 2014. The centriole duplication cycle. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130460 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0460) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beisson J, Wright M. 2003. Basal body/centriole assembly and continuity. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 96–104. ( 10.1016/S0955-0674(02)00017-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gull K. 1999. The cytoskeleton of trypanosomatid parasites. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53, 629–655. ( 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.629) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piel M, Meyer P, Khodjakov A, Rieder CL, Bornens M. 2000. The respective contributions of the mother and daughter centrioles to centrosome activity and behavior in vertebrate cells. J. Cell Biol. 149, 317–330. ( 10.1083/jcb.149.2.317) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salisbury JL, Baron A, Surek B, Melkonian M. 1984. Striated flagellar roots: isolation and partial characterization of a calcium-modulated contractile organelle. J. Cell Biol. 99, 962–970. ( 10.1083/jcb.99.3.962) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wright RL, Salisbury J, Jarvik JW. 1985. A nucleus-basal body connector in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii that may function in basal body localization or segregation. J. Cell Biol. 101, 1903–1912. ( 10.1083/jcb.101.5.1903) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taillon BE, Adler SA, Suhan JP, Jarvik JW. 1992. Mutational analysis of centrin: an EF-hand protein associated with three distinct contractile fibers in the basal body apparatus of Chlamydomonas. J. Cell Biol. 119, 1613–1624. ( 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1613) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Delaval B, Covassin L, Lawson ND, Doxsey S. 2011. Centrin depletion causes cyst formation and other ciliopathy-related phenotypes in zebrafish. Cell Cycle 10, 3964–3972. ( 10.4161/cc.10.22.18150) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Middendorp S, Paoletti A, Schiebel E, Bornens M. 1997. Identification of a new mammalian centrin gene, more closely related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC31 gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 9141–9146. ( 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9141) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Araki M, Masutani C, Takemura M, Uchida A, Sugasawa K, Kondoh J, Ohkuma Y, Hanaoka F. 2001. Centrosome protein centrin 2/caltractin 1 is part of the xeroderma pigmentosum group C complex that initiates global genome nucleotide excision repair. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18 665–18 672. ( 10.1074/jbc.M100855200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dantas TJ, Wang Y, Lalor P, Dockery P, Morrison CG. 2011. Defective nucleotide excision repair with normal centrosome structures and functions in the absence of all vertebrate centrins. J. Cell Biol. 193, 307–318. ( 10.1083/jcb.201012093) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dantas TJ, Daly OM, Conroy PC, Tomas M, Wang Y, Lalor P, Dockery P, Ferrando-May E, Morrison CG. 2013. Calcium-binding capacity of centrin2 is required for linear POC5 assembly but not for nucleotide excision repair. PLoS ONE 8, e68487 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0068487) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arquint C, Gabryjonczyk A-M, Nigg EA. 2014. Centrosomes as signalling centres. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130464 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0464) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nachury MV. 2014. How do cilia organize signalling cascades? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130465 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0465) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stinchcombe JC, Griffiths GM. 2014. Communication, the centrosome and the immunological synapse. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130463 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0463) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Holy TE, Dogterom M, Yurke B, Leibler S. 1997. Assembly and positioning of microtubule asters in microfabricated chambers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 6228–6231. ( 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6228) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ishihara K, Nguyen PA, Wühr M, Groen AC, Field CM, Mitchison TJ. 2014. Organization of early frog embryos by chemical waves emanating from centrosomes. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130454 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0454) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rios RM. 2014. The centrosome–Golgi apparatus nexus. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130462 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0462) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reina J, Gonzalez C. 2014. When fate follows age: unequal centrosomes in asymmetric cell division. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130466 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0466) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schliwa M, Pryzwansky KB, Euteneuer U. 1982. Centrosome splitting in neutrophils: an unusual phenomenon related to cell activation and motility. Cell 31, 705–717. ( 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90325-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agircan FG, Schiebel E, Mardin BR. 2014. Separate to operate: control of centrosome positioning and separation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130461 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0461) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Godinho SA, Pellman D. 2014. Causes and consequences of centrosome abnormalities in cancer. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130467 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0467) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chavali PL, Pütz M, Gergely F. 2014. Small organelle, big responsibility: the role of centrosomes in development and disease. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369, 20130468 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0468) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Delattre M, Gönczy P. 2004. The arithmetic of centrosome biogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 117, 1619–1630. ( 10.1242/jcs.01128) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tassin AM, Maro B, Bornens M. 1985. Fate of microtubule-organizing centers during myogenesis in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 100, 35–46. ( 10.1083/jcb.100.1.35) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]