Abstract

Background

Insulin resistance and other cardiometabolic risk factors predict increased risk of depression and decreased response to antidepressant and mood stabilizer treatments. This proof-of-concept study tested whether administration of an insulin-sensitizing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ) agonist could reduce bipolar depression symptom severity. A secondary objective determined if levels of highly-sensitive C-reactive protein and Interleukin-6 (IL-6) predicted treatment outcome.

Methods

Thirty-four patients with bipolar disorder (I, II, or not otherwise specified) and metabolic syndrome/insulin resistance who were currently depressed (Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS) total score ≥ 16) despite an adequate trial of a mood stabilizer received open-label, adjunctive treatment with the PPAR- γ agonist pioglitazone (15–30 mg/d) for 8 weeks. The majority of participants (76%, n=26) were experiencing treatment-resistant bipolar depression, having already failed two mood stabilizers or the combination of a mood stabilizer and a conventional antidepressant.

Results

Supporting an association between insulin sensitization and depression severity, pioglitazone treatment was associated with a decrease in the total Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-C30) score from 38.7±8.2 at baseline to 21.2±9.2 at week 8 (p<.001). Self-reported depressive symptom severity and clinician-rated anxiety symptom severity significantly improved over 8 weeks as measured by the QIDS (p<.001) and Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (p<.001), respectively. Functional improvement also occurred as measured by the change in total score on the Sheehan Disability Scale (−17.9±3.6; p<.001). Insulin sensitivity increased from baseline to week 8 as measured by the Insulin Sensitivity Index derived from an oral glucose tolerance test (0.98±0.3; p<.001). Higher baseline levels of IL-6 were associated with greater decrease in depression severity (parameter estimate β=−3.89, SE=1.47, p=0.015). A positive correlation was observed between improvement in IDS-C30 score and change in IL-6 (r=0.44, p<01).

Conclusions

Open-label administration of the PPAR-γ agonist, pioglitazone, was associated with improvement in depressive symptoms and reduced cardiometabolic risk. Reduction in inflammation may represent a novel mechanism by which pioglitazone modulates mood. (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00835120)

1. INTRODUCTION

Previous research has identified a link between cardiometabolic illnesses, mood symptoms, and response to psychotropic medications. Type-2 diabetes (T2DM) [1], the metabolic syndrome [2,3], and visceral adiposity [4] are associated with the development of clinically significant depression, while insulin resistance is correlated with greater depression severity [5,6]. In addition, bipolar depressive episodes accompanied by cardiometabolic illness appear more refractory to mood stabilizer treatment [7]. Focusing on this shared pathophysiology that uniquely links cardiometabolic disease with the development of abnormal mood states [8,9], we hypothesized in 2009 that reducing insulin resistance may lead to an improvement in depressive symptom severity [8].

Pioglitazone is an insulin sensitizer commonly used in the treatment of T2DM that reduces insulin resistance by activating peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs), with greatest specificity for PPAR-γ. Central nervous system PPAR-γ receptors regulate insulin sensitizing effects in peripheral tissues [10] and are also hypothesized to influence mood and behavior.

1.1 Inflammatory activation and insulin resistance have the potential to modulate mood

Several inflammatory biomarkers, including highly-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are commonly elevated in depressed patients with bipolar disorder [11]. Data indicate that inflammatory cytokines can reduce the concentration of tryptophan and other monoamine precursors through activation of enzymes such as 2,3-dioxygenase, shifting conversion of tryptophan from serotonin into kynurenine and generating neuroactive metabolites that can significantly influence the regulation of dopamine and glutamate [12]. Inflammatory cytokines have also been shown to inhibit neurogenesis through the activation of nuclear factor κβ (NF- κβ), a pathway concurrently implicated in the pathogenesis of hepatic insulin resistance [13–15]. In a subset of patients, each of these inflammatory processes appears to contribute significantly to the development and maintenance of major depressive episodes. However, inflammatory pathways are not the primary mechanistic targets of conventional mood stabilizers. Given that PPAR- γ agonists inhibit the expression of inflammatory genes and modulate oxidative stress-sensitive pathways [16], both of which are mechanisms implicated in the pathophysiology of depression, the role of PPAR-γ agonists as potential antidepressant therapies warrants further study [11].

Changes in insulin resistance may also modulate mood by influencing the release and reuptake of monoamine neurotransmitters [17]. Diet-induced insulin resistance produces profound effects on nigrostriatal neurons by attenuating dopamine release and uptake [18]. Insulin also acts as a neuromodulator, influencing presynaptic regulation of dopamine transporter function in the nucleus accumbens [19]. In addition, evidence points to an underlying abnormality of mitochondria in bipolar disorder, resulting in sustained oxidative stress and impaired neuronal function. Resistance to insulin signaling impairs synaptic plasticity by making neurons energy deficient and more vulnerable to oxidizing free radicals, further potentiating oxidative stress and altering dopamine signaling events [20]. Pharmacologic agents that improve insulin sensitivity have therefore been hypothesized to possess antidepressant properties [8, 21].

1.2 Antidepressant-like effects of pioglitazone in murine models

Animal studies using the forced swimming test (FST) and tail suspension test have identified PPAR-γ agonists as possessing antidepressant-like activity [22,23]. In mice, the immobility time in the FST was significantly decreased after pioglitazone administration [23], an effect that was reversed when a PPAR-γ antagonist was administered. In addition, the co-administration of non-effective doses of pioglitazone and an NMDA antagonist, as well as a non-effective dose of N(G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester ( L-NAME), a non-specific nitric oxide (NO) synthase inhibitor, significantly reduced immobility time. Together, these findings implicate alterations in nuclear receptors, the nitrergic system, and NMDA receptors as partial mediators of the antidepressant-like changes associated with administration of PPAR-γ agonists [8,24].

1.3 Demonstrating clinical proof-of-concept for PPAR-γ agonists in bipolar depression

The identification of novel mechanisms for treating bipolar depression is an urgent unmet need, as major depressive episodes dominate the course of bipolar disorder and generally represent the most debilitating dimension of the illness [13,25]. Despite the substantial morbidity associated with bipolar depression, there exist few pharmacologic treatments effective at treating this pole of the disorder. Currently, quetiapine, lurasidone, and the combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine are the only medications approved by the US FDA for the treatment of bipolar depression [26–30]. However, atypical antipsychotics are often encumbered by cardiometabolic side effects, including the potential to induce hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, and T2DM [9, 31].

We have previously reported that treatment with pioglitazone in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) accompanied by metabolic syndrome was associated with improvement in mood [24]. Sepanjnia and colleagues in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial found the combination of pioglitazone and citalopram rapidly improved depressive symptoms to a greater extent than citalopram alone, even among patients without metabolic syndrome or T2DM [32].

Extending upon these findings, the present study demonstrates proof-of-concept for pioglitazone to modulate mood in patients with bipolar disorder experiencing a major depressive episode insufficiently responsive to a mood stabilizer. The ability of PPAR-γ agonists to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce inflammation is well documented [16]. PPAR-γ ligands have been shown to inhibit TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β expression in monocytes, and PPARs negatively regulate the transcription of inflammatory responses genes by antagonizing the activator protein-1 and NF- κβ signaling pathways [16, 33]. Therefore, we measured inflammatory markers (e.g. IL-6) and parameters of insulin resistance throughout the study to determine if these variables were associated with change in depression severity, the primary outcome of interest. In so doing, we sought to identify novel neurobiological mechanisms relevant to depression and generate potential new targets for antidepressant efficacy.

2. METHODS

Proof-of-concept was investigated in an 8-week, open-label study that evaluated pioglitazone administration to subjects with bipolar disorder experiencing a major depressive episode of at least moderate severity (QIDS score ≥ 16) despite treatment with a mood stabilizer. The trial was conducted at the Mood & Metabolic Clinic of University Hospitals Case Medical Center at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, OH, USA after approval by the Institution Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to participation. Participants were enrolled from April 2009 to September 2011.

2.1 Patient population

Outpatients aged 18 to 70 years who met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria for the diagnosis of bipolar disorder(I, II, or not otherwise specified) and metabolic syndrome (see below), and who were currently experiencing a major depressive episode without psychotic features were eligible for inclusion in the study. A current diagnosis of bipolar depression was confirmed using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [34]. Participants were required to have a patient-rated, 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS) [35] score ≥11 and to meet criteria for metabolic syndrome as established by the National Cholesterol Education Program's Adult Treatment Panel III [36] or proxy criteria for insulin resistance as evidenced by 2 or more of the following: body mass index (BMI) ≥ 28, fasting blood glucose ≥ 100 mg/dl, triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dl, or triglyceride/HDL-cholesterol ratio ≥ 3.0. Patients were excluded if they had an unstable medical condition, were taking insulin or rosiglitazone, met criteria for dependence on alcohol or drugs within 3 months prior to enrollment, had a history of heart failure, or had clinically relevant manic symptoms as defined by a Young Mania Rating Scale score ≥ 15.

2.2 Study medication

Pioglitazone tablets were obtained from Takeda Pharmaceuticals. During conduct of the study, pioglitazone became available as a generic preparation and was subsequently obtained from Amerisource-Bergen. Open-label pioglitazone was administered as adjunctive therapy to one or more mood stabilizers (aripiprazole, carbamazepine, divalproex, lamotrigine, lithium, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone) over 8 weeks and initiated at 15mg daily in a single dose. After 4 weeks, a dose titration of pioglitazone to 30 mg daily was permitted. Dose changes of the mood stabilizer or any concomitant psychotropic medications were not permissible either within 4 weeks of receiving pioglitazone or during the study itself. Receipt of lorazepam or zolpidem for anxiety or insomnia was permitted.

2.3 Efficacy evaluations

Clinical assessments were conducted at baseline and then at Weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8. Efficacy was measured using the mean change from baseline to Week 8 on the clinician-administered 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS-C30) [35]. Secondary analyses included an assessment of anxiety symptoms by the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Scale [37], global symptom severity by the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scales for change and severity of illness [38], self-assessment of depression symptom severity by the QIDS [35], and functional disability by the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) [39].

2.4 Medical and laboratory assessments

A detailed medical and psychiatric history was performed, including a physical examination, where anthropometric measurements were obtained such as height, weight and waist circumference. Laboratory assessments were conducted at baseline, Week 4, and study endpoint (Week 8) and consisted of a basic chemistry panel, complete blood count, thyroid and liver function tests, fasting lipid profile, and urine toxicology for drugs of abuse. Women of childbearing potential had urine pregnancy tests at study inception and used two forms of medically accepted birth control throughout the trial. Adverse events were elicited by both spontaneous report and direct verbal query. Insulin sensitivity was estimated by the Insulin Sensitivity Index (ISI) [40] derived from an oral glucose tolerance test as well as by the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), a widely used surrogate measure that is calculated by: (fasting insulin (µU/ml))×(fasting glucose (mg/dl))÷22.5 [41]. The serum IL-6 concentration was measured by quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay (RnD Systems Inc.). All samples were assayed in duplicate. Inter-assay and intra-assay coefficients of variation were reliably less than 8%.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Simple descriptive statistics (mean±SD) were obtained for the patients' demographic and baseline clinical characteristics. The data were log transformed where necessary to satisfy the normality assumption required by the statistical test. The primary and secondary efficacy analyses were performed on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which included all patients who took at least one dose of study medication and had at least one post-baseline efficacy assessment. The primary a priori endpoint was symptom severity as assessed by the change from baseline to final assessment in the IDS-C30 total scores. The outcome measures CGI severity and total scores on the IDS-C30, SIGH-A, QIDS, and SDS were analyzed using mixed-model repeated-measures (MMRM) regression analysis. In the MMRM models, patient was treated as a random effect and visit week as a fixed effect. Either unstructured or first-order auto-regressive matrices were specified as the appropriate structure for the variance–covariance matrix used to describe the relationship among the time (visit week) data points. Means and standard deviations or standard errors are reported. Eight-week changes from baseline were assessed using linear contrasts on the MMRM models. Overall mean change in cardiometabolic and inflammatory biomarkers were calculated for each patient and analyzed for statistical significance using a level set at α = 0.05. Analyses were also conducted on the effect of baseline inflammatory status as assessed by plasma IL-6 concentration on change in depression severity over time, as well as change in depression severity over time by change in inflammatory status from baseline to weeks 4 and 8. The effects of inflammatory markers and insulin resistance on antidepressant outcome to pioglitazone were tested using linear mixed models fitted with maximum likelihood and linear regression models. A two-tailed p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant; p-values were not adjusted for multiplicity of comparisons. Response was defined as a ≥50% reduction in IDS-C30 or QIDS total score. Remission was defined as an IDS-C30 total score ≤12 or QIDS total score ≤ 5, respectively. Data were analyzed using SAS software (SAS for Windows, version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3. RESULTS

3.1 Patients and disposition

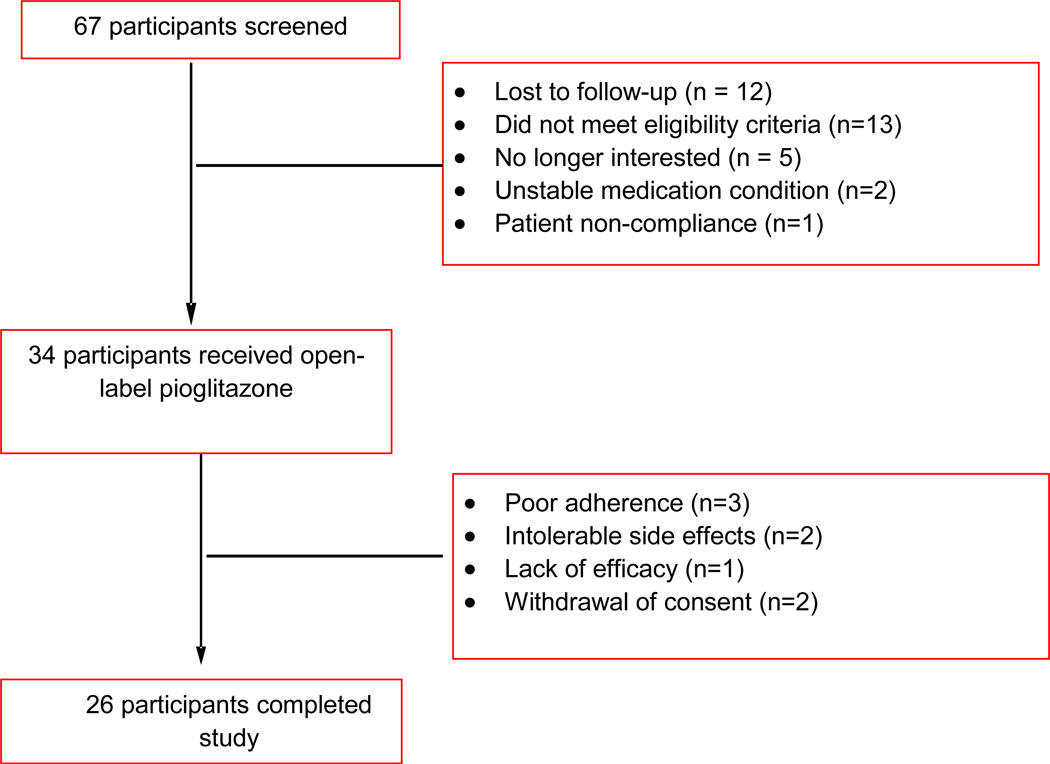

Sixty-seven patients consented for participation in the study. Thirty-three participants were either ineligible or chose not to participate (Fig. 1). Thirty-four participants were enrolled and received open-label pioglitazone; the mean daily dose of pioglitazone was 27.4 ± 5.8 mg (range 15–30 mg/day). A summary of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics is presented in Table 1. Fifty-six percent (n=19) were female and 71% (n=24) were Caucasian. Lifetime generalized anxiety disorder was diagnosed in 74% (n=25) of participants and 56% (n=19) had a lifetime history of an alcohol use disorder. Seventy-six percent (n=26) of subjects were considered treatment-resistant, having already failed at least two mood stabilizers or the combination of a mood stabilizer and a conventional antidepressant during the current episode [412, 43]. Two (6%) patients discontinued due to increased activation/irritability that was possibly related to pioglitazone. Twenty-six (76%) participants completed the entire 8 weeks of the study.

Figure 1. Disposition of Patients with Bipolar Depression Receiving Pioglitazone.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics of Patients Treated with Pioglitazone for Bipolar Depression (N=34)

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 47.8 | 10.9 |

| Age of depression onset (yr) | 17.8 | 10.9 |

| Age of mania/hypomania onset (yr) | 23.5 | 19.2 |

| Age first treated for depression (yr) | 34.7 | 11.3 |

| Age first treated for mania/hypomania (yr) | 40.8 | 12.0 |

| Duration of mood state (d) | 315.5 | 331.6 |

| Number of prior hospitalizations | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| Number of prior suicide attempts | 1.2 | 2.0 |

| N | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 15 | 44.1 |

| Female | 19 | 55.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White/Caucasian | 24 | 70.6 |

| Black/African-American | 9 | 26.5 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 2.9 |

| Employed | 12 | 35.3 |

| Bipolar Subtype | ||

| Bipolar 1 | 27 | 79.4 |

| Bipolar 2 | 5 | 14.7 |

| Bipolar not otherwise specified | 2 | 5.9 |

| Medication treatment failures during current episode | ||

| ≥ 2 mood stabilizers or a mood stabilizer + antidepressant | 26 | 76.5 |

| ≥ 4 mood stabilizers or antidepressants | 15 | 44.1 |

| Comorbid diagnoses | ||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 25 | 73.5 |

| Panic disorder | 11 | 32.4 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 12 | 35.3 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 5 | 14.7 |

| Alcohol use disorder, lifetime | 19 | 55.9 |

| History of physical abuse | 10 | 29.4 |

| History of verbal abuse | 14 | 41.2 |

| History of sexual abuse | 9 | 26.5 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 32 | 94.1 |

| Insulin resistance | 30 | 88.2 |

3.2 Efficacy at 8 weeks

Pioglitazone significantly reduced symptoms of depression across both clinician- and patient-rated assessments of depression severity (Table 2). The total mean IDS-C30 score decreased from 38.7±8.2 at baseline to 21.2±9.2 at endpoint (p<.001). Self-reported assessments of depression symptom severity reflected a similar improvement; mean QIDS scores decreased from 16.1±3.4 at baseline to 8.9±5.0 (p<.001). Anxiety symptoms decreased significantly according to the SIGH-A total score, decreasing from a mean of 19.0±6.1 at baseline to 8.9±5.0 (p<.001). The mean CGI-BP severity score also decreased from 4.6±0.5 to 2.7±1.3 (p<.001). The categorical response criteria were met by 38% (N=13) of patients on both the IDS-C30 and QIDS at the acute phase endpoint. Remission of depressive symptoms was achieved by 24% (N=8) of patients on both the IDS-C30 and QIDS. Functional disability also improved significantly over the course of 8 weeks as measured by the baseline to endpoint change on the SDS (−17.9±3.6; p<.001).

Table 2.

Psychiatric Outcome Measures in an Open-Label Pioglitazone Trial in Patients with Bipolar Depression and Metabolic Syndrome/Insusulin Resistance (N=34)

| Outcome measure | Baseline | Week 8 | Change Week 8* | t-value | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | LS Mean | SEM | |||

| Depressive symptoms | ||||||||||

| IDS total score | 34 | 38.7 | 8.2 | 26 | 21.2 | 9.2 | −16.5 | 2.6 | −6.33 | <.001 |

| QIDS total score | 34 | 16.1 | 3.4 | 26 | 8.9 | 5.0 | −7.1 | 1.2 | −6.01 | <.001 |

| Anxiety symptoms | ||||||||||

| SIGH-A total score | 34 | 19 | 6.1 | 26 | 9.4 | 4.6 | −8.9 | 1.7 | −5.21 | <.001 |

| Global severity of illness | ||||||||||

| CGI-Severity | 34 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 26 | 2.7 | 1.3 | −1.9 | 0.3 | −7.30 | <.001 |

| Sheehan Disability Scale | ||||||||||

| Total | 16 | 28.4 | 9.3 | 16 | 12.4 | 10.5 | −17.9 | 3.6 | −4.92 | <.001 |

| Work | 20 | 6.0 | 3.1 | 18 | 2.8 | 2.3 | −3.3 | 1.0 | −3.45 | 0.001 |

| Social | 32 | 6.4 | 2.8 | 26 | 3.8 | 3.3 | −3.8 | 0.9 | −4.28 | <0.001 |

| Family | 32 | 6.3 | 2.6 | 26 | 3.5 | 3.3 | −4 | 0.8 | −4.72 | <.001 |

Least squares mean (LS Mean) change from baseline to Week 8 determined by mixed model analysis to accomodate for missing values

CGI=Clinical Global Impressions scale; IDS=Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology; QIDS=Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms; SD=Standard deviation; SEM=Standard error of LS Mean; SIGH-A=Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Scale

When analyzing baseline to endpoint change among only those participants who completed the entire study (n=26) as compared with the intent-to-treat sample (n=34), Cohen’s d effect sizes were similar as measured by the IDS-C30 (1.7 vs. 1.8, respectively) and QIDS (1.7 vs. 1.5, respectively).

3.3 Inflammatory biomarkers

Levels of inflammatory cytokines decreased over 8 weeks of treatment with pioglitazone, including a significant reduction in highly-sensitive C-reactive protein (−3.03±2.14; p<.01) as reported in Table 3. A trend was observed for the mean decrease from baseline to Week 8 in the concentration of IL-6 (−0.42±0.46 pg/ml; p=0.06). The Spearman correlation coefficient revealed a significant positive relationship between the overall change in IDS-C30 total score and change from baseline in IL-6 (r=0.44, p<.01). Moreover, the linear mixed model repeated-measures analyses revealed a significant effect of change in IL-6 (p=0.008) on change in the primary outcome of IDS-C30 total score. A linear regression model also indicated that higher levels of baseline IL-6 were related to a greater decrease in IDS-C30 total scores over the course of the 8-week study (parameter estimate β=−3.89, SE=1.47, p=0.015). No significant correlations were observed between changes in hs-CRP or TNF-α and change in IDS-C30 total score. In a linear regression model, no association was identified between hs-CRP, ISI, or HOMA-IR and change in depression severity.

Table 3.

Cardiometabolic Outcome Measures in an 8-Week Study of Pioglitazone-Treated Subjects with Bipolar Depression

| Baseline | Week 8 | Change from Baseline to Week 8* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | LS Mean | SEM | t-value | P value | |

| Anthropometric measurements | ||||||||||

| Blood pressure systolic (mmHg) | 34 | 125.6 | 13.5 | 26 | 125.3 | 11.5 | −0.37 | 3.56 | −0.06 | 0.95 |

| Blood pressure diastolic (mmHg) | 34 | 78.9 | 13.7 | 26 | 76.4 | 7.4 | −2.22 | 2.46 | −0.45 | 0.65 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 34 | 36.2 | 5.8 | 26 | 37.3 | 6.1 | 0.07 | 0.68 | 0.1 | 0.92 |

| Waist circumference (in) | 34 | 44.0 | 5.1 | 25 | 44.7 | 6.0 | 0.5 | 1.01 | 0.3 | 0.77 |

| Weight (kg) | 34 | 104.5 | 21.4 | 26 | 108.3 | 22.5 | 0.26 | 2.19 | 0.11 | 0.91 |

| Glucose metabolism measurements | ||||||||||

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dl) | 33 | 105.2 | 24.5 | 25 | 99.2 | 31.0 | −7.71 | 3.78 | −2.59 | 0.01 |

| Fasting serum insulin (IU/ml) | 27 | 24.1 | 12.4 | 23 | 21.7 | 13.5 | −2.48 | 3.19 | −0.97 | 0.34 |

| Insulin Sensitivity Index | 28 | 1.90 | 0.75 | 22 | 2.59 | 1.06 | 0.98 | 0.3 | 3.66 | <.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 27 | 6.28 | 3.67 | 23 | 5.47 | 3.45 | −0.89 | 0.93 | −1.12 | 0.27 |

| Triglyceride/HDL-C ratio | 33 | 3.95 | 1.66 | 25 | 2.91 | 1.69 | −1.01 | 0.35 | −3.05 | <.01 |

| Adiponectin µg/ml | 33 | 7.56 | 4.93 | 25 | 14.1 | 10.04 | 6.82 | 1.45 | 10.39 | <.001 |

| Lipid panel | ||||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 33 | 199.2 | 41.1 | 25 | 185.9 | 38.0 | −11.65 | 7.61 | −1.53 | 0.13 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 33 | 173.7 | 71.9 | 25 | 125.9 | 60.9 | −46.15 | 14.76 | −3.12 | <.01 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 33 | 114.0 | 36.7 | 25 | 112.5 | 34.0 | 0.04 | 8.04 | 0.01 | 0.99 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 33 | 45.6 | 11.4 | 25 | 48.2 | 14.4 | 2.6 | 2.19 | 1.11 | 0.27 |

| Inflammatory biomarker measurements | ||||||||||

| Highly sensitive C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 32 | 6.03 | 6.68 | 25 | 3.92 | 5.32 | −3.03 | 2.14 | −2.75 | <.01 |

| Interleukin-10 (pg/ml) | 33 | 6.99 | 11.84 | 25 | 8.16 | 15.98 | 1.14 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.38 |

| Interleukin-6 (pg/ml) | 33 | 1.92 | 1.09 | 25 | 1.53 | 0.95 | −0.42 | 0.46 | −1.95 | 0.06 |

| Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (pg/ml) | 33 | 8.21 | 1.75 | 25 | 7.76 | 1.77 | −0.42 | 0.31 | −1.35 | 0.18 |

Least squares mean (LSMean) change from baseline to Week 8 determined by mixed model analysis to accommodate for missing values.

HDL-C=High density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR=Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance; LDL-C=Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

3.5 Glucose and lipid metabolism

Effects of pioglitazone on anthropometric measurements, glucose, lipoproteins, and inflammatory biomarkers are shown in Table 3. Patients experienced a significant decrease from baseline in fasting plasma glucose (− 7.7±3.8 mg/dl; p=.01). Insulin sensitivity assessed by the ISI increased significantly by 40% over 8 weeks (0.98±0.3; p<.001). The fasting lipid profile analyses showed a significant reduction in triglycerides (−46.2±14.8;p<.01) from baseline to the Week 8 endpoint. Concentrations of adiponectin, a protein hormone involved in glucose regulation, increased nearly two-fold, from 7.6 ug/ml to 14.1 ug/ml over 8 weeks.

3.6 Treatment–emergent adverse events

The most common adverse events were dizziness, irritability, increased appetite, and peripheral edema; each occurred in 11.7% (n=4) of participants. No participants developed clinically significant weight gain (≥7% body weight). The mean body weight of patients increased non-significantly by 0.26 ± 2.9 kg (p=.91) over 8 weeks.

4. DISCUSSION

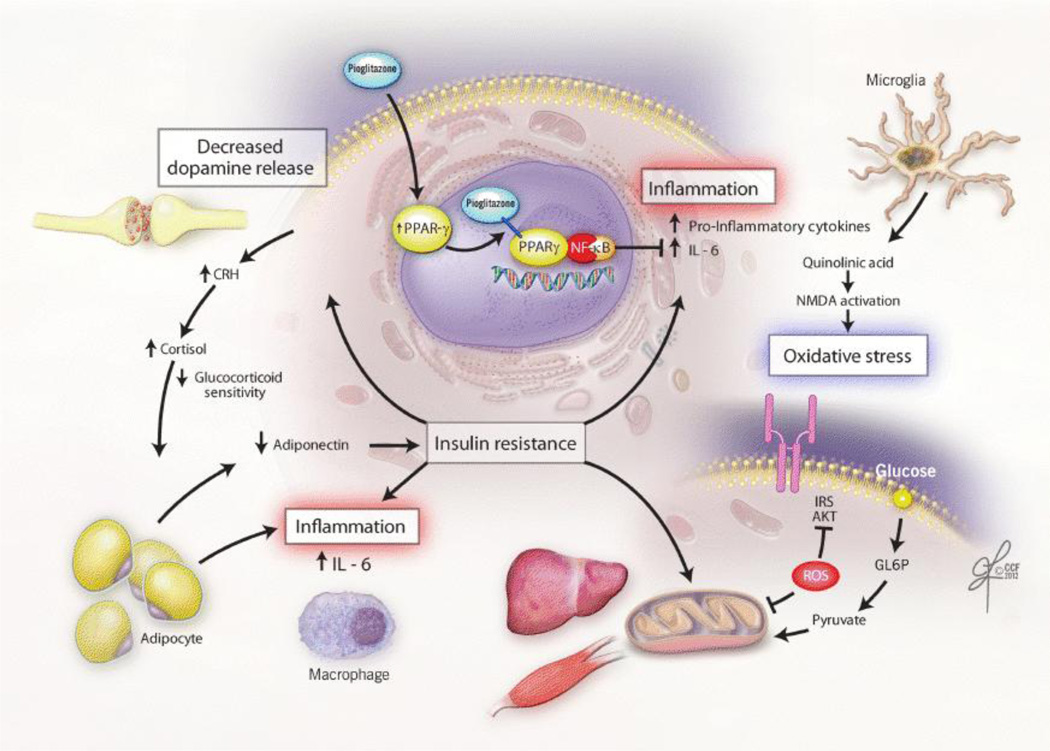

In an effort to uncover a novel treatment to stabilize mood from below baseline in bipolar disorder [44], we focused on the overlapping pathophysiology that links inflammatory activation and insulin resistance with depressed mood (Figure 2). In this proof-of-concept study we report for the first time putative evidence of efficacy and safety of the PPAR-γ agonist pioglitazone in acute bipolar depression. The trial results indicate significant improvement in depressive symptoms following 8 weeks of pioglitazone treatment. Additionally, pioglitazone was associated with improvement in fasting glucose, triglycerides, and total body insulin resistance.

Figure 2. Proposed Pathways by which Insulin Resistance Mediates the Development and Maintenance of Depressive Symptoms.

Figure 2 illustrates the pathways by which factors associated with insulin resistance are conceptualized to mediate the development and maintenance of depressive symptoms. A chronic, low-grade inflammatory state within visceral adipose tissue contributes to insulin resistance through activation of inflammatory signaling cascades within immune cells (e.g. macrophages) [58,59]. In addition, reduced secretion of adiponectin by adipocytes directly lowers insulin sensitivity and is inversely correlated with depression severity [48,60]. Although cortisol serves to inhibit the inflammatory response, over-activation of the HPA-axis in response to stress leads to visceral adiposity and further disruption of hepatic glucoregulatory mechanisms. Additionally, insulin resistance leads to alterations in dopamine release and oxidative damage to pancreatic beta-cells and the brain. Insulin resistance is reversed within the central nervous system and periphery through activation of brain PPAR-γ. By attenuating insulin resistance, inducing neuroprotection, and decreasing inflammation, PPAR-γ activation is hypothesized to modulate mood. AKT=Protein kinase B; CRH=Corticotropin-releasing hormone; GL6P=glucose 6-phosphate; HPA=hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; IL-6=Interleukin-6; IRS=Insulin receptor substrate; NF-κB=Nuclear factor kappa B;NMDA= N-methyl-D-aspartate;PPAR-γ=peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma; ROS=Reactive oxygen species

Analyses exploring potential mechanisms of antidepressant action suggest that blood levels of the IL-6 cytokine (a biomarker of inflammation) may be mechanistically involved in pioglitazone’s mood-modulating properties. Baseline levels of IL-6 predicted treatment outcome, with higher IL-6 associated with greater improvement on the IDS-C30. In addition, reduction in IL-6 was significantly correlated with greater improvement in depressive symptoms, such that participants who experienced larger decreases in IL-6 also had a larger reduction in depression severity scores.

In contrast to our finding that associated higher baseline IL-6 with a larger decrease in depression severity with pioglitazone treatment, prior studies have identified higher levels of IL-6 to be associated with poorer response to antidepressants [45, 46]. These findings may indicate that pioglitazone preferentially relieves depression in patients with higher levels of IL-6, who may have presumably failed traditional mood stabilizers directly or indirectly because of an elevation in inflammation. Rethorst and colleagues recently postulated this effect in patients receiving exercise augmentation for major depressive disorder, where patients with high TNF-α levels experienced more rapid improvement in depression severity [47].

Change in levels of adiponectin may also represent a mechanism that partially accounts for the antidepressant effect observed in this study. Adiponectin is an adipocyte-derived hormone with anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing properties, linking together the immune system with cardiometabolic factors that are known to be associated with depression. Recent studies have identified reduced levels of adiponectin in human subjects with major depression [48], while in animal models, disruption of the adipocytokine signaling pathway appears to be a critical component of the manifestation of depressive-like behaviors. As an example, in a social-defeat stress model of depression, a reduction in adiponectin levels resulted in increased susceptibility to anhedonia, social aversion, and learned helplessness. In contrast, exogenous administration of adiponectin resulted in antidepressant-like behavioral effects in both normal-weight and obese diabetic mice [49]. Consistent with prior reports that PPAR- γ agonists can increase plasma levels of adiponectin by two- to three-fold [49,50], adiponectin concentrations nearly doubled in the present study and may represent one mechanism to compensate for the elevation of inflammatory parameters observed in patients with bipolar disorder [52].

In this sample of predominantly treatment-resistant patients, a protocol defined response occurred in 38% (n=13) of participants, and 24% (n=8) met criteria for remission. Although these response and remission rates are lower than observed in traditional placebo-controlled trials that apply strict eligibility criteria, the outcomes are comparable to more generalizable populations with bipolar disorder who, like participants in the present study, suffer from comorbid anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and general medical conditions. In addition, over 74% (n=24) of the enrolled population met criteria for treatment-resistant bipolar depression, having already failed two mood stabilizers or the combination of a mood stabilizer and an antidepressant [42, 43]. Recovery rates in such patients are remarkably low. For example, in a trial conducted by the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) of patients who had not responded to the combination of a mood stabilizer and a conventional antidepressant, recovery rates with open-label lamotrigine and risperidone were 24% and 5%, respectively [43]. These outcomes confirm the chronic and enduring quality of bipolar depressive episodes and underscore the need for novel therapies with unique mechanisms of action.

Rather than worsening the cardiometabolic milieu as often occurs with currently marketed agents for the treatment of bipolar depression, pioglitazone appears to decrease cardiometabolic risk. Pioglitazone-treated patients experienced a significant reduction in total cholesterol, fasting triglycerides, and hs-CRP, a biomarker of inflammation implicated in the risk of both first incident and recurrent cardiovascular events [53]. These effects on the atherogenic profile may account for the observed reduction in all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and stroke when pioglitazone was administered to patients with T2DM and macrovascular disease [54].

Overall pioglitazone was very well tolerated, with no serious adverse events reported. Although weight gain has been observed with pioglitazone in studies of T2DM [55], the increase in body weight in the present trial averaged 0.48 kg, a non-significant difference from baseline. Metabolic abnormalities in patients with mood disorders present clinicians with a challenging situation, as existing treatments for bipolar depression (i.e. quetiapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination) are associated with an increased risk for weight gain, hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia [31]. In contrast, the preliminary findings from this study suggest that pioglitazone may reduce depression severity and simultaneously mitigate the worrisome cardiometabolic risks that affect more than one-third of the population with bipolar disorder. Consistent with NIMH initiatives, the clinical insights gained from this pilot investigation may be an example of how to speed the drug discovery process by repurposing an existing drug rather than requiring the discovery of a new clinical entity [56].

Strengths of the present study include enrollment of a broadly representative population of patients with bipolar disorder, administration of validated measures of depressive symptomatology, and use of a structured clinical interview to diagnose bipolar depression. Use of a frequently-sampled oral glucose tolerance test provided a more definitive method to quantify insulin sensitivity and is more accurate than the minimal model technique [57]. Unlike HOMA-IR, the ISI does not assume that hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity are equivalent [40].

Consistent with the ISI being a more robust measure of insulin sensitivity, a significant improvement in insulin sensitivity was observed using the ISI that was not observed with HOMA-IR. A known action of pioglitazone is to increase insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues including adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and liver. Whether such a phenomenon occurs in the CNS and whether such an effect mediates the observed response of depression to pioglitazone requires further study.

The results of this study should also be interpreted in the context of several limitations. These data are uncontrolled and open-label. The sample size was small and may have led to underestimation of potential side effects that could emerge when pioglitazone is administered to a large population with bipolar depression. Additional studies are needed to replicate the mechanistic finding that improvement in depression severity may result from a decrease in the concentration of IL-6. Pioglitazone may have been under-dosed, as 30 mg daily was the maximum permitted dose, whereas the approved dosing for T2DM extends to 45 mg daily. It is not known whether pioglitazone has mood stabilizing properties or results in a bimodal response, managing not only the manifestations of depression but also manic and mixed phases of the illness. However, such trials are warranted as there was little evidence of switching or exacerbation of manic symptoms in this cohort.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we present evidence that suggests intervention with the PPAR-γ agonist, pioglitazone, was associated with clinically meaningful reductions in depression severity in predominantly treatment-refractory patients with bipolar depression. Reduction in symptom severity was directly correlated with a decrease in levels of IL-6, suggesting that anti-inflammatory activity may partially account for the observed antidepressant response, representing a novel mechanism of mood modulation. In total, these data support the conduct of larger, placebo-controlled trials to fully delineate the role of pioglitazone in the treatment of patients with bipolar depression.

Key Points.

Given that Insulin resistance and other cardiometabolic risk factors predict increased risk of depression and decreased response to antidepressant and mood stabilizer treatments, this proof-of-concept study tested whether administration of the insulin-sensitizer, pioglitazone, could reduce the severity of bipolar depression symptoms.

Patients with bipolar disorder in a current major depressive episode and treated with the PPAR-gamma agonist, pioglitazone, experienced a reduction in depression severity as well as improvement in several markers of insulin resistance.

A significant positive correlation was observed between improvement in depression severity and change in IL-6. Reduction in inflammation may represent a novel mechanism by which pioglitazone modulates mood.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This study was funded in part by the Cleveland Foundation, NARSAD, and NIH grant 1KL2RR024990 to Dr. Kemp. Study medication was partially supplied by Takeda Pharmaceuticals. The project described was supported by Grant Number UL1 RR024989 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Previous presentation: New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit Annual Meeting, Boca Raton, Florida, June 14–17, 2012

Disclosures:

Dr. Kemp has served on a speakers bureau for AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Sunovion, Lundbeck, and Takeda. He has been a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corcept, Janssen, and Teva.

Dr. Gao has received research support from AstraZeneca, NARSAD, Sunovion, and the Cleveland Foundation.

Dr. Ganocy has received research support from Eli Lilly and AstraZeneca

Dr. Ismail-Beigi is a shareholder in Thermalin Inc.

Dr. Calabrese has received research support from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Cleveland Foundation, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, NARSAD, Repligen, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Takeda, and Wyeth; he has consulted to or served on advisory boards of Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Dainippon Sumitomo, EPI-Q, Inc., Forest, France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, Neurosearch, OrthoMcNeil, Otsuka, Pfizer, Repligen, Schering-Plough, Servier, Solvay, Supernus, Synosia, Takeda, and Wyeth; and he has provided CME lectures supported by AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Johnson andJohnson, Merck, Sanofi Aventis, Schering-Plough, Pfizer, Solvay, and Wyeth.

Dr. Schinagle and Ms. Conroy have no disclosures to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Golden SH, Lazo M, Carnethon M, Bertoni AG, Schreiner PJ, Diez Roux AV, et al. Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. JAMA. 2008;299:2751–2759. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koponen H, Jokelainen J, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Kumpusalo E, Vanhala M. Metabolic syndrome predisposes to depressive symptoms: a population-based 7-year follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:178–182. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan A, Keum N, Okereke OI, Sun Q, Kivimaki M, Rubin RR, et al. Bidirectional association between depression and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1171–1180. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogelzangs N, Kritchevsky SB, Beekman AT, Brenes GA, Newman AB, Satterfield S. Obesity and onset of significant depressive symptoms: results from a prospective community-based cohort study of older men and women. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:391–399. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04743blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timonen M, Rajala U, Jokelainen J, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Meyer-Rochow VB, Rasanen P. Depressive symptoms and insulin resistance in young adult males: results from the Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:929–933. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timonen M, Salmenkaita I, Jokelainen J, Laakso M, Härkönen P, Koskela P. Insulin resistance and depressive symptoms in young adult males: findings from Finnish military conscripts. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:723–728. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318157ad2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kemp DE, Gao K, Chan PK, Ganocy SJ, Findling RL, Calabrese JRC. Medical comorbidity in bipolar disorder: relationship between illnesses of the endocrine/metabolic system and treatment outcome. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:404–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kemp DE, Ismail-Beigi F, Calabrese JR. Antidepressant response associated with pioglitazone: support for an overlapping pathophysiology between major depression and metabolic syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:619. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08081195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemp DE, Fan J. Cardiometabolic health in bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Annals. 2012;42:179–183. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20120507-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan KK, Li B, Grayson BE, Matter EK, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. A role for central nervous system PPAR-gamma in the regulation of energy balance. Nat Med. 2011;17:623–626. doi: 10.1038/nm.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haroon E, Raison CL, Miller AH. Psychoneuroimmunology meets neuropsychopharmacology: translational implications of the impact of inflammation on behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:137–162. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raison CL, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, Lawson MA, Woolwine BJ, Vogt G. CSF concentrations of brain tryptophan and kynurenines during immune stimulation with IFN-alpha: relationship to CNS immune responses and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:393–403. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koo JW, Duman RS. IL-1beta is an essential mediator of the antineurogenic and anhedonic effects of stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:751–756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708092105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleemann R, van Erk M, Verschuren L, van den Hoek AM, Koek M, Wielinga PY. Time-resolved and tissue-specific systems analysis of the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. PloS One. 2010;5:e8817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Leon AC, Solomon DA. Psychosocial disability in the course of bipolar I and II disorders: a prospective, comparative, longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1322–1330. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delerive P, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in inflammation control. J Endocrinol. 2001;169:453–459. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1690453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosco D, Fava A, Plastino M, Montalcini T, Pujia A. Possible implications of insulin resistance and glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1807–1821. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris JK, Bomhoff GL, Gorres BK, Davis VA, Kim J, Lee PP. Insulin resistance impairs nigrostriatal dopamine function. ExpNeurol. 2011;231:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoffelmeer AN, Drukarch B, De Vries TJ, Hogenboom F, Schetters D, Pattij T. Insulin modulates cocaine-sensitive monoamine transporter function and impulsive behavior. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1284–1291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3779-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovestone S, Killick R, Di Forti M, Murray R. Schizophrenia as a GSK-3 dysregulation disorder. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIntyre RS, Vagic D, Swartz SA, Soczynska JK, Woldeyohannes HO, Voruganti LP, Konarski JZ. Insulin, insulin-like growth factors and incretins: neural homeostatic regulators and treatment opportunities. CNS Drugs. 2008;22:443–453. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eissa Ahmed AA, Al-Rasheed NM. Antidepressant-like effects of rosiglitazone, a PPARgamma agonist, in the rat forced swim and mouse tail suspension tests. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20:635–642. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328331b9bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadaghiani MS, Javadi-Paydar M, Gharedaghi MH, Fard YY, Dehpour AR. Antidepressant-like effect of pioglitazone in the forced swimming test in mice: The role of PPAR-gamma receptor and nitric oxide pathway. Behav Brain Res. 2011;224:336–343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kemp DE, Ismail-Beigi F, Ganocy SJ, Conroy C, Gao K, Obral S, et al. Use of insulin sensitizers for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a pilot study of pioglitazone for major depression accompanied by abdominal obesity. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:1164–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530–537. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calabrese JR, Keck PE, Jr., Macfadden W, Minkwitz M, Ketter TA, Weisler RH, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1351–1360. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kemp DE, Muzina DJ, McIntyre RS, Calabrese JR. Bipolar depression: trial-based insights to guide patient care. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10:181–192. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.2/dekemp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, Ketter TA, Sachs G, Bowden C, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1079–1088. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, Kroger H, Hsu J, Sarma K, et al. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070984. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, Kroger H, Xu J, Calabrese JR. Lurasidone as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate for the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070985. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Gao K, Kemp DE. Second-generation antipsychotics in major depressive disorder: update and clinical perspective. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:10–17. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283413505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sepanjnia K, Modabbernia A, Ashrafi M, Modabbernia MJ, Akhondzadeh S. Pioglitazone adjunctive therapy for moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2093–2100. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature. 1998;391:82–86. doi: 10.1038/34184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;59(Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 4–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Biggs MM, Suppes T, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med. 2004;34:73–82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shear MK, Vander Bilt J, Rucci P, Endicott J, Lydiard B, Otto MW, et al. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A) Depress Anxiety. 2001;13:166–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, revised. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leon AC, Shear MK, Portera L, Klerman GL. Assessing impairment in patients with panic disorder: the Sheehan Disability Scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992;27:78–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00788510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1462–1470. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diazgranados N, Ibrahim L, Brutsche NE, Newberg A, Kronstein P, Khalife S. A randomized add-on trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:793–802. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nierenberg AA, Ostacher MJ, Calabrese JR, Ketter TA, Marangell LB, Miklowitz DJ. Treatment-resistant bipolar depression: a STEP-BD equipoise randomized effectiveness trial of antidepressant augmentation with lamotrigine, inositol, or risperidone. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:210–216. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ketter TA, Calabrese JR. Stabilization of mood from below versus above baseline in bipolar disorder: a new nomenclature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:146–151. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benedetti F, Lucca A, Brambilla F, Colombo C, Smeraldi E. Interleukine-6 serum levels correlate with response to antidepressant sleep deprivation and sleep phase advance. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:1167–1170. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshimura R, Hori H, Ikenouchi-Sugita A, Umene-Nakano W, Ueda N, Nakamura J. Higher plasma interleukin-6 (IL-6) level is associated with SSRI- or SNRI-refractory depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:722–726. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rethorst CD, Toups MS, Greer TL, Nakonezny PA, Carmody TJ, Grannemann BD. Pro-inflammatory cytokines as predictors of antidepressant effects of exercise in major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:1119–1124. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cizza G, Nguyen VT, Eskandari F, Duan Z, Wright EC, Reynolds JC, et al. Low 24-hour adiponectin and high nocturnal leptin concentrations in a case-control study of community-dwelling premenopausal women with major depressive disorder: the Premenopausal, Osteopenia/Osteoporosis, Women, Alendronate, Depression (POWER) study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1079–1087. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05314blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu J, Guo M, Zhang D, Cheng SY, Liu M, Ding J, et al. Adiponectin is critical in determining susceptibility to depressive behaviors and has antidepressant-like activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12248–12253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202835109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu JG, Javorschi S, Hevener AL, Kruszynska YT, Norman RA, Sinha M, et al. The effect of thiazolidinediones on plasma adiponectin levels in normal, obese, and type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 2002;51:2968–2974. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang WS, Jeng CY, Wu TJ, Tanaka S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, et al. Synthetic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist, rosiglitazone, increases plasma levels of adiponectin in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:376–380. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barbosa IG, Rocha NP, de Miranda AS, Magalhães PV, Huguet RB, de Souza LP, et al. Increased levels of adipokines in bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Emerging Risk Factors C, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Lowe G, Pepys MB, Thompson SG, et al. C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:132–140. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61717-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, Erdmann E, Massi-Benedetti M, Moules IK, et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspectivepioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shah P, Mudaliar S. Pioglitazone: side effect and safety profile. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2010;9:347–354. doi: 10.1517/14740331003623218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brady LS, Insel TR. Translating discoveries into medicine: psychiatric drug development in 2011. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:281–283. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saad MF, Anderson RL, Laws A, Watanabe RM, Kades WW, Chen YD, et al. A comparison between the minimal model and the glucose clamp in the assessment of insulin sensitivity across the spectrum of glucose tolerance.Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes. 1994;43:1114–1121. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.9.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fleet-Michaliszyn SB, Soreca I, Otto AD, Jakicic JM, Fagiolini A, Kupfer DJ, et al. A prospective observational study of obesity, body composition, and insulin resistance in 18 women with bipolar disorder and 17 matched control subjects. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1892–1900. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fried SK, Bunkin DA, Greenberg AS. Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin-6: depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:847–850. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim S, Koo BK, Cho SW, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Cho YM, et al. Association of adiponectin and resistin with cardiovascular events in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes: the Korean atherosclerosis study (KAS): a 42-month prospective study. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]