Abstract

Purpose of review

This review highlights recent insights of the roles of microRNAs in pathogenesis of myeloid malignancies and tantalising prospects of microRNA therapy.

Recent findings

New roles for microRNAs in biological and disease processes are constantly being discovered. However, while great effort has been put into identifying and cataloguing aberrantly expressed microRNAs in leukaemia, very little is known about the functional consequences of their deregulation in myeloid malignancies. This review will discuss the significance of powerful oncogenic microRNAs such as miR-22 in self-renewal and transformation of hematopoietic stem cells, as well as their ability to induce epigenetic alterations in the pathogenesis of the stem cell disorder MDS and myeloid leukaemia.

Summary

Improved understanding of biological roles of microRNAs in pathogenesis of hematological malignancies will allow rational stratification of patients and provide new therapeutic entries for the treatment of MDS and leukaemia.

Keywords: microRNAs, miR-22, TET2, myelodysplastic syndromes, acute myeloid leukaemia

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding RNAs with a length of approximately 22 nucleotides, which bind to imperfect matches to the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) and other regions of target mRNAs/RNAs molecules, and thus repress their translation and/or stability. This is accomplished by forming a ribonucleoprotein complex called an RISC (RNA-induced Silencing Complex), that contains an Argonaute family member. Mature miRNAs are generated by a multi-step process that begins with the initial transcription of their genes by RNA polymerase II, resulting in capped large polyadenylated primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs), which can be several hundred to thousands of nucleotides long. These pri-miRNAs are then processed in the nucleus by the ribonuclease (RNase) III Drosha–DGCR8 microprocessor complex into hairpin-structure precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) of 60~100 nucleotides. The pre-miRNAs are then translocated by exportin 5–RanGTP shuttle system to the cytoplasm, in which Dicer, an RNase III-like enzyme, further processes them into mature miRNAs [1].

miRNAs have been shown to play key regulatory roles in all facets of biology including cell proliferation, differentiation, development, apoptosis, metabolism, and hematopoiesis [2]. The importance of miRNAs in blood cancers was first indicated by the discovery that the majority of miRNAs are located at fragile sites and cancer-associated genomic regions [3], and there is now overwhelming evidence that aberrant expression of miRNAs is a common hallmark of hematological malignancies and solid tumours. Functional analyses as well as animal models have shown the contribution of miRNAs to the pathogenesis of hematological malignancies through the modulation of cancer-associated oncogenes or tumour suppressor genes, or in the case of myeloid disorders, through the regulation of epigenetic mechanisms.

This review will focus on recent insights into the roles of miRNAs in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and myeloid leukaemia, with a detailed discussion of the tantalising prospect that miRNAs may in future serve as therapeutic targets.

miRNAs in MDS

MDS are hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) disorders characterized by ineffective differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors, bone marrow dysplasia, and a propensity to develop acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). As the molecular mechanisms of MDS development are poorly understood, effective treatment options are often limited. Recent progress has been made, however, in identifying altered signalling pathways and understanding HSC defects that may contribute to the pathogenesis of MDS. Importantly, more than 70% of all human miRNAs are located within regions of recurrent copy-number alterations in MDS and AML cell lines [4]. Moreover, targeted deletion of Dicer1 in osteoprogenitor cells has been found to result in abnormal hematopoiesis, MDS, and AML, suggesting that global down-regulation of miRNAs by Dicer1 deletion may promote myeloid malignancies [5]. Several recent studies have demonstrated aberrant expression of miRNAs in MDS patients using microarray-based platforms. For example, Hussein et al. demonstrated that the miRNA expression signature in bone marrow (BM) cells from 24 MDS patients and 3 control samples can distinguish MDS entities with chromosomal alterations from the patients with a normal karyotype [6]. Sokol et al. also examined global miRNA expression in BM mononuclear cells isolated from 44 MDS patients and 17 normal controls and found high levels of miR-222, miR-10a and low levels of miR-146a, miR-150, and Let-7e in MDS [7] (Table 1). Furthermore, distinctive miRNA expression profiles in CD34+ BM cells from seven 5q- syndrome patients showed overexpression of miR-34a and down-regulation of miR-146a [8]. Vasilatou et al. recently evaluated the expression patterns of let-7a, miR-17-5p and miR-20a in CD34+ HSCs from the bone marrow of 43 MDS patients and the peripheral blood of 18 healthy donors, and found that these miRNAs are up-regulated in low risk MDS patients but down-regulated in high risk MDS patients [9]. However, there are very few overlapping miRNAs among these studies, which may reflect the heterogeneity of the disease but also may possibly be due to variations between the sample processing and miRNA detection protocols. Although there is accumulating evidence that multiple miRNAs are aberrantly expressed in HSCs from MDS patients and deregulated miRNAs have been intensively pursued in the field, the functions of miRNAs in MDS development and their therapeutic potential remain largely undefined. Identifying the putative targets of miRNAs in MDS and developing proper animal models of MDS are critical to achieving this goal.

Table 1.

Implications of miRNAs in human MDS and myeloid malignancies

| miRNAs | Disease type | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| miR-222 | High in MDS | [7, 8] |

| miR-10a | High in MDS, AML | [7, 26] |

| miR-146a | Low in MDS | [7] |

| miR-150 | Low in MDS | [7] |

| let-7a | Low in MDS | [7, 9] |

| miR-34a | High in MDS | [8] |

| miR-17-5p | Low in MDS | [9] |

| miR-20a | Low in MDS | [9] |

| miR-22 | High in MDS, AML | [10, 23] |

| miR-382 | High in AML | [23] |

| miR-134 | High in AML | [23] |

| miR-376a | High in AML | [23] |

| miR-127 | High in AML | [23] |

| miR-299-5p | High in AML | [23] |

| miR-323 | High in AML | [23] |

| let-7b | Low in AML | [23] |

| let-7c | Low in AML | [23] |

| miR-126 | High in AML | [24] |

| miR-224 | Low in AML | [24] |

| miR-368 | Low in AML | [24] |

| miR-382 | Low in AML | [24] |

| miR-17~92 | High in AML, CML | [25, 44] |

| miR-196b | High in AML | [26, 27] |

| miR-29 | High in AML | [26] |

| miR-204 | Low in AML | [24] |

| miR-128a | Low in AML | [24] |

| miR-155 | High in AML | [23, 26] |

| miR-181a, miR-181b | High in AML | [30] |

| miR-1 | High in AML | [31] |

| miR-133 | High in AML | [31] |

| miR-124a | Low in AML | [33] |

| miR-223 | Low in AML | [34] |

| miR-193a | Low in AML | [35] |

| miR-203 | Low in CML | [45] |

| miR-138 | Low in CML | [46] |

Our recent study has demonstrated that constitutive miR-22 overexpression in mice enhances the proliferative capacity of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) accompanied by defective differentiation [10■■]. Interestingly, miR-22 overexpressing transgenic mice developed MDS over time. In co-transplantation experiments, miR-22 overexpression caused HSPCs to progressively outcompete their wild-type counterparts. Furthermore, when observed for longer periods of time, transplanted HSPCs overexpressing miR-22 gave rise to a disease reminiscent of MDS, which subsequently progressed to full-blown acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Importantly, miR-22 was found to be highly expressed in human MDS and its aberrant expression correlated with poor survival rates in MDS patients. Unexpectedly, miR-22 overexpression in the hematopoietic compartment resulted in a reduction in the levels of global 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC), and conversely, an increase of 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) levels, suggesting that miR-22 impacts the global epigenetic landscape in blood cells. Epigenetic changes and clinical responses to agents that reverse aberrant hypermethylation, such as 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine and 5-azacytidine, have implied a contribution from aberrant hypermethylation to the pathogenesis of MDS [11, 12]. Whole genome scanning for DNA methylation patterns in MDS patients has also revealed a global hypermethylation signature, which is associated with rapid transformation to AML and poor prognosis [13]. In support of these observations, the methylcytosine dioxygenase TET, which converts 5-mC to 5-hmC, is frequently deleted or inactivated in MDS patients and results in defective conversion of 5-mC [14]. The contribution of TET2 inactivation to MDS has been demonstrated by the rapid onset of myeloproliferative and MDS features in Tet2 knockout mice [15–17]. Furthermore, our comprehensive analysis of MDS patients has identified down-regulation of TET2 protein levels as a common event in MDS (35.5% of total 107 MDS patient samples and 22.2% of 18 AML samples with multiple lineage dysplasia (MLD)) and a factor in poor prognosis [10]. Importantly, these findings imply that the contribution of TET2 to the pathogenesis of MDS might be related to more than its mutation and will impact the management and therapeutic decisions for MDS patients.

Notably, the phenotypes elicited by miR-22 overexpression closely phenocopy the inactivation of Tet2 in the hematopoietic system both in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, while Tet2 expression increases during hematopoietic differentiation [16], miR-22 is highly expressed in HSPCs and its expression declines in mature cells. These initial observations led us to test whether miR-22 could act as an authentic TET2-targeting microRNA in the hematopoietic compartment by utilizing miR-22 transgenic mouse model. Indeed, a series of bioinformatic, luciferase reporter and RIP (RNA immunoprecipitation; Song et al., in preparation) analyses revealed TET2 as a legitimate target possessing critically conserved miR-22 seed matches [10, 18■■]. Consistent with these observations, miR-22 overexpression resulted in a marked reduction in levels of Tet2 mRNA and protein and a concomitant decrease in expression of known Tet2 target genes, such as Aim2 (Absence in myeloma 2) and Sp140 (SP140 nuclear body protein). It is interesting to note that TET2 mutations do not seem to always translate to increased promoter methylation of genes, with AIM2 and SP140 being notable exceptions [19, 20]. AIM2 and SP140 have been implicated in cell-cycle arrest and susceptibility to chronic lymphoid leukaemia (CLL) [21, 22], however, their possible role(s) in the pathogenesis of MDS requires further investigation.

miRNAs in myeloid leukaemia

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is a heterogeneous group of neoplastic hematopoietic diseases characterized by the accumulation of primitive myeloid cells arrested at early stages of differentiation. The presence of one of many specific cytogenetic abnormalities has been found in around 55% of AML patients. Of particular interest, miRNA expression profiling studies have revealed marked differences in miRNA expression between common cytogenetic subtypes of AML, including those harbouring favourable-risk abnormalities such as t(8,21), inv(16), and t(15,17), as well as those with less favourable-risk subtypes such as t(11q23)/MLL (mixed lineage leukaemia) and trisomy 8 cases. For example, Jongen-Lavrencic et al. demonstrated a strong up-regulation of miR-382, miR-134, miR-376a, miR-127, miR-299-5p, and miR-323 in AML patients with t(15;17) and a significant down-regulation of let-7b and let-7c in AML with t(8;21) and also in AML with inv(16) [23]. Li et al. found that miR-126 is specifically overexpressed in both t(8;21) and inv(16) AMLs, whereas miR-224, miR-368, and miR-382 are almost exclusively overexpressed in t(15;17) AML [24]. Mi et al. showed that the miR-17~92 cluster is aberrantly overexpressed in MLL-rearranged AML [25]. miR-196b, located between the homeobox A9 (HOXA9) and HOXA10 genes, is another miRNA which has been found to be specifically overexpressed in AML patients with MLL rearrangements [26, 27].

The miRNA signatures in AML patients harbouring normal karyotype (namely, cytogenetically normal AML (CN-AML)) have been reported to be associated with recurrent molecular abnormalities including nucleophosmin (NPM1), internal tandem duplication of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3-ITD), CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha (C/EBPα), isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1), or IDH2 mutations [28, 29]. For instance, Garzon et al. found an up-regulation of miR-10, let-7 and miR-29 family members and a down-regulation of miR-204 and miR-128a in AML patients carrying NPM1 mutations [26]. Importantly, two independent groups reported that miR-155 is up-regulated in AML patients harbouring FLT3-ITD mutations, suggesting a role for this miRNA in the highly proliferative phenotype of this subset of AML [23, 26]. Additionally, Marcucci et al. identified highly expressed miR-181a and miR-181b associated with C/EBPα mutations in CN-AML [30]. In their follow-up study, Marcucci et al. reported up-regulation of miR-1 and miR-133 in IDH2-mutated CN-AML patients compared with the IDH1/IDH2 wild-type patients [31].

In addition to chromosomal alterations causing aberrant miRNA expression, the regulation of miRNAs mediated by alterations in epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation and histone code, might also play an important role in AML pathogenesis [32]. For example, in AML patient samples the aberrant methylation of miR-124a has been found independently of the cytogenetic subtype and its epigenetic silencing and its silencing was associated with regulation of EVI1 [33]. Additionally, Fazi et al. reported that AML1-ETO induces heterochromatic silencing of miR-223 [34]. Gao et al. showed that miR-193a is down-regulated due to hypermethylation of its promoter region in AML patients, and its expression was inversely correlated with its target, c-KIT [35].

Importantly, we have demonstrated that miR-22 is a powerful regulator of HSPC maintenance and self-renewal and in that process skews hematopoietic differentiation, mainly toward myelopoiesis, triggering overt AML [10]. Furthermore, when we analysed the expression levels of miR-22 in a large cohort of AML patients [23], miR-22 was found highly expressed in 58.1% of 214 AML patient samples when compared to normal BM from healthy donors. Although our study may help in the re-classification of subtypes of MDS, and possibly AML, on the basis of miR-22 expression, further investigation is required into whether its expression profiling in AML patients is associated with specific chromosomal aberrations. Importantly, our findings implicate the deregulation of the miR-22-TET2 pathway as a common event in the pathogenesis of MDS and AML; however, the mechanisms that control the expression of miR-22 are still unidentified. Interestingly, recent studies have demonstrated that the PI3K/AKT pathway or c-Myc activates mir-22 gene transcription [36, 37, 38■]. Extensive evidence has also accrued that the PI3K/AKT pathway is aberrantly activated and deregulated in AML patients, and constitutive AKT activation has been linked to poor prognosis in AML [39, 40]. Additionally, c-Myc is frequently activated in AML patients and its importance in the pathogenesis of AML has been demonstrated in mouse models overexpressing c-Myc in BM progenitors [41, 42].

Aberrant expression of miRNAs has also been observed in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML). CML is a clonal myeloproliferative disorder arising from neoplastic transformation of a single HSC. The hallmark of the disease in approximately 95% of all patients is the presence of a Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome which arises from a reciprocal translocation t(9; 22) (q34; q11) that creates a BCR-ABL fusion oncogene [43]. Like in MDS and AML, miRNAs also display aberrant expression in CML cells. For example, up-regulation of the miR-17~92 cluster was found to be associated with the chronic phase but not blast crisis in CML patients [44]. The association of miRNAs with BCL-ABL has been further illustrated by finding that miR-203, which is epigenetically silenced in CML patients, can regulate BCL-ABL expression [45]. miR-138, down-regulated in CML cells but restored in response to imatinib treatment, was also recently found to target BCR-ABL [46]. Because it has been recently demonstrated that decreased TET2 gene expression associated with t(4;6;11) rearrangement may be involved in CML progression [47], it will be interesting to further analyse miR-22 expression profiling in CML patients.

miR-22 as a novel therapeutic target in myeloid malignancies

Different leukaemia types and subtypes have specific miRNA signatures that may be useful as diagnostic and prognostic markers. Furthermore, there is a growing body of evidence that circulating miRNAs can leave “fingerprints” indicating the progress of various diseases [48–50]. miRNAs can also be packaged into multivesicular bodies and released into the extracellular environment as exosomes. In a recent finding of particular interest, systemic characterization of exosomal RNA profiles (by utilizing RNA sequencing analysis in human plasma samples) revealed miR-22 as one of the most common exosomal miRNAs among all mappable miRNA sequences [51■]. Furthermore, Zhu et al. recently identified maternal circulating miR-22 as a novel non-invasive biomarker for prenatal detection of fetal congenital heart defects (CHD) [52]. In addition, many correlations between circulating miRNA levels and response to a given anticancer agent have been observed, and may be useful in predicting patterns of resistance and sensitivity to specific drugs. For example, it was recently demonstrated that circulating miR-22 is elevated in a subset of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and that this high expression correlates with a lack of response to treatment with the drug pemetrexed, indicating that circulating miR-22 could represent a novel predictive biomarker for the efficacy of pemetrexed-based treatment [53]. Likewise, the characterization of circulating miR-22 in patients with MDS and myeloid leukaemia is expected to provide similar treatment profiles, and open new doors for the development of promising novel plasma-based biomarkers for myeloid malignancies.

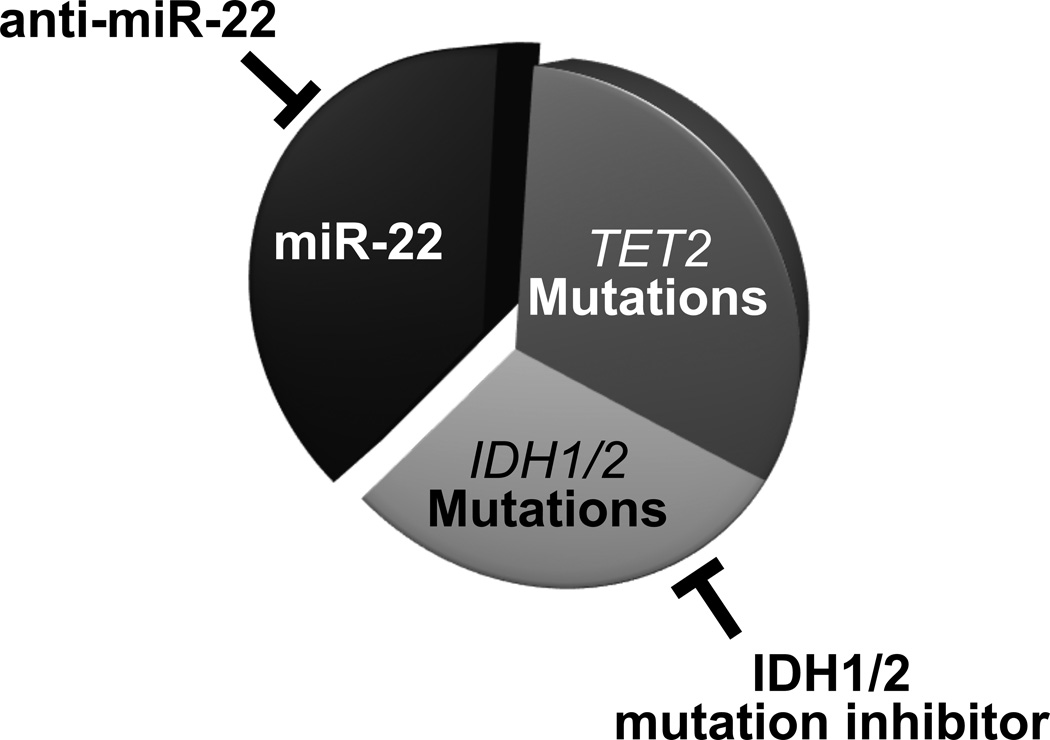

However, beyond the identification of novel cancer biomarkers, miRNA-based therapy is now coming of age. The first cancer-targeted miRNA drug, MRX34 (a liposome-based miR-34 mimic) recently entered Phase I clinical trials in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and is attracting considerable attention from both academic researchers and pharmaceutical companies [54]. Additionally, new technologies to inhibit miRNAs as a therapeutic strategy are also rapidly evolving, and could lead to treatment options for a range of diseases in the years to come [55■]. Indeed, our findings that inhibiting miR-22 with a decoy leads to a reduction of metastatic phenotypes in the breast, and that treatment with a LNA (locked nucleic acid)-modified miR-22 decoy results in a significant reduction in leukemic cell proliferation [10, 18], strongly support the notion that it may be worth developing and testing LNA-based targeting of miR-22 as a treatment modality for MDS and myeloid leukaemia. The modulation of oncogenic miR-22 activity by LNA-anti-miR-22 could represent a promising therapeutic approach for a large number of leukaemia patients, either alone or in combination with currently used therapies. Much as the clinical importance of miR-22’s role in the epigenetic triggers of leukaemogenesis has been demonstrated in the examples above, so research into combinatorial treatment with LNA-anti-miR-22 decoys plus de-methylating agents or inhibitors of histone de-acetylases may soon reveal a further untapped therapeutic potential of LNA-anti-miR-22-based therapeutic modalities. Indeed, recent identification of a selective mutant IDH1 inhibitor (AGI-5198) that blocks the production of 2-hydroxyglutarate (an oncometabolite which inhibits TET2 catalytic activity [56, 57, 58■■]) further underscores the potential therapeutic advantages for leukaemia patients of combined use of LNA-anti-miR-22 and mutant IDH1 inhibitors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. miR-22 as a novel therapeutic target in myeloid malignancies.

In MDS and AML, TET is functionally lost by TET2 mutations, IDH1/2 mutations or high expression of miR-22. Thus, either miR-22 decoying alone or in combination with IDH1/2 mutant inhibitors could offer the potential therapeutic advantages for leukaemia patients.

Conclusion

Growing evidence describes the roles of miRNAs in various hematopoietic malignancies, including MDS and myeloid leukaemia. Notably, recent findings have identified the deregulation of the miR-22-TET2 pathway as a common event in myeloid malignancies and imply that the contribution of TET2 to the pathogenesis of myeloid malignancies could be related to more than its mutations. Importantly, they also provide a compelling rationale for targeted therapies that impact the mechanisms of aberrant regulation of TET2 observed in MDS and AML through miR-22 decoying.

Highlights of the review.

Great effort has recently been devoted to identifying and cataloguing aberrantly expressed microRNAs in leukaemia.

Oncogenic microRNAs, such as miR-22, dictate the self-renewal and transformation of hematopoietic stem cells.

miR-22 alters the epigenetic landscape to trigger the pathogenesis of the stem cell disorder MDS as well as myeloid leukaemia.

Targeting powerful oncogenic microRNAs may lead to new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of MDS and leukaemia.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the Pandolfi laboratory for their comments and discussion. We are grateful to Thomas Garvey for critical editing of the manuscript. This work was supported by CA141457-03 NIH grants to P.P.P.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

■ of special interest

■■ of outstanding interest

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gangaraju VK, Lin H. MicroRNAs: key regulators of stem cells. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2009;10:116–125. doi: 10.1038/nrm2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starczynowski DT, Morin R, McPherson A, et al. Genome-wide identification of human microRNAs located in leukemia-associated genomic alterations. Blood. 2011;117:595–607. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-277012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raaijmakers MH, Mukherjee S, Guo S, et al. Bone progenitor dysfunction induces myelodysplasia and secondary leukaemia. Nature. 2010;464:852–857. doi: 10.1038/nature08851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussein K, Theophile K, Busche G, et al. Significant inverse correlation of microRNA-150/MYB and microRNA-222/p27 in myelodysplastic syndrome. Leuk Res. 2010;34:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokol L, Caceres G, Volinia S, et al. Identification of a risk dependent microRNA expression signature in myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 2011;153:24–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dostalova Merkerova M, Krejcik Z, Votavova H, et al. Distinctive microRNA expression profiles in CD34+ bone marrow cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:313–319. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasilatou D, Papageorgiou SG, Kontsioti F, et al. Expression analysis of mir-17-5p, mir-20a and let-7a microRNAs and their target proteins in CD34+ bone marrow cells of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res. 2013;37:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Song SJ, Ito K, Ala U, et al. The oncogenic microRNA miR-22 targets the TET2 tumor suppressor to promote hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and transformation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.06.003. The authors demonstrate that miR-22 is highly expressed in patients with MDS and AML, and miR-22-overexpressing transgenic mice show an increase of HSC self-renewal accompanied by defective differentiation and develop MDS and hematological malignancies through targeting TET2.

- 11.Issa JP. Epigenetic changes in the myelodysplastic syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24:317–330. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szmigielska-Kaplon A, Robak T. Hypomethylating agents in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes and myeloid leukemia. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:837–848. doi: 10.2174/156800911796798940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang Y, Dunbar A, Gondek LP, et al. Aberrant DNA methylation is a dominant mechanism in MDS progression to AML. Blood. 2009;113:1315–1325. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-163246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delhommeau F, Dupont S, Della Valle V, et al. Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360:2289–2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z, Cai X, Cai CL, et al. Deletion of Tet2 in mice leads to dysregulated hematopoietic stem cells and subsequent development of myeloid malignancies. Blood. 2011;118:4509–4518. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran-Crusio K, Reavie L, Shih A, et al. Tet2 loss leads to increased hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and myeloid transformation. Cancer cell. 2011;20:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quivoron C, Couronne L, Della Valle V, et al. TET2 inactivation results in pleiotropic hematopoietic abnormalities in mouse and is a recurrent event during human lymphomagenesis. Cancer cell. 2011;20:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Song SJ, Poliseno L, Song MS, et al. MicroRNA-antagonism regulates breast cancer stemness and metastasis via TET-family-dependent chromatin remodeling. Cell. 2013;154:311–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.026. The authors identify miR-22 as a crucial epigenetic modifier and promoter of mammary epithelial-mesenchymal transition and breast cancer stemness toward metastasis through antagonizing TET-miR-200.

- 19.Ko M, Huang Y, Jankowska AM, et al. Impaired hydroxylation of 5-methylcytosine in myeloid cancers with mutant TET2. Nature. 2010;468:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature09586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamazaki J, Taby R, Vasanthakumar A, et al. Effects of TET2 mutations on DNA methylation in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Epigenetics. 2012;7:201–207. doi: 10.4161/epi.7.2.19015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Bernardo MC, Crowther-Swanepoel D, Broderick P, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies six susceptibility loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1204–1210. doi: 10.1038/ng.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patsos G, Germann A, Gebert J, Dihlmann S. Restoration of absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and promotes invasion of colorectal cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1838–1849. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jongen-Lavrencic M, Sun SM, Dijkstra MK, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling in relation to the genetic heterogeneity of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:5078–5085. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, Lu J, Sun M, et al. Distinct microRNA expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia with common translocations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15535–15540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808266105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mi S, Li Z, Chen P, et al. Aberrant overexpression and function of the miR-17–92 cluster in MLL-rearranged acute leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3710–3715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914900107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garzon R, Volinia S, Liu CG, et al. MicroRNA signatures associated with cytogenetics and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:3183–3189. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-098749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Popovic R, Riesbeck LE, Velu CS, et al. Regulation of mir-196b by MLL and its overexpression by MLL fusions contributes to immortalization. Blood. 2009;113:3314–3322. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-154310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J, Odenike O, Rowley JD. Leukaemogenesis: more than mutant genes. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2010;10:23–36. doi: 10.1038/nrc2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao H, Wang D, Du W, et al. MicroRNA and leukemia: tiny molecule, great function. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;74:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcucci G, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, et al. Prognostic significance of, gene and microRNA expression signatures associated with, CEBPA mutations in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia with high-risk molecular features: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5078–5087. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcucci G, Maharry K, Wu YZ, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 gene mutations identify novel molecular subsets within de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2348–2355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agirre X, Martinez-Climent JA, Odero MD, Prosper F. Epigenetic regulation of miRNA genes in acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26:395–403. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vazquez I, Maicas M, Marcotegui N, et al. Silencing of hsa-miR-124 by EVI1 in cell lines and patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:E167–E168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011540107. author reply E169–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fazi F, Zardo G, Gelmetti V, et al. Heterochromatic gene repression of the retinoic acid pathway in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2007;109:4432–4440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-045781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao XN, Lin J, Li YH, et al. MicroRNA-193a represses c-kit expression and functions as a methylation-silenced tumor suppressor in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2011;30:3416–3428. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bar N, Dikstein R. miR-22 forms a regulatory loop in PTEN/AKT pathway and modulates signaling kinetics. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song SJ, Pandolfi PP. miR-22 in tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:11–12. doi: 10.4161/cc.27027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Polioudakis D, Bhinge AA, Killion PJ, et al. A Myc-microRNA network promotes exit from quiescence by suppressing the interferon response and cell-cycle arrest genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:2239–2254. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1452. The authors demonstrate that miRNA miR-22 promotes proliferation in primary human cells, is activated by Myc, and that miR-22 inhibits the Myc transcriptional repressor MXD4, mediating a feed-forward loop to elevate Myc expression levels.

- 39.Kornblau SM, Womble M, Qiu YH, et al. Simultaneous activation of multiple signal transduction pathways confers poor prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:2358–2265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Min YH, Eom JI, Cheong JW, et al. Constitutive phosphorylation of Akt/PKB protein in acute myeloid leukemia: its significance as a prognostic variable. Leukemia. 2003;17:995–997. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slovak ML, Ho JP, Pettenati MJ, et al. Localization of amplified MYC gene sequences to double minute chromosomes in acute myelogenous leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;9:62–67. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870090111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo H, Li Q, O'Neal J, et al. c-Myc rapidly induces acute myeloid leukemia in mice without evidence of lymphoma-associated antiapoptotic mutations. Blood. 2005;106:2452–2461. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sawyers CL. Chronic myeloid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;340:1330–1340. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904293401706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venturini L, Battmer K, Castoldi M, et al. Expression of the miR-17–92 polycistron in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) CD34+ cells. Blood. 2007;109:4399–4405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-045104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bueno MJ, Perez de Castro I, Gomez de Cedron M, et al. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of microRNA-203 enhances ABL1 and BCR-ABL1 oncogene expression. Cancer cell. 2008;13:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu C, Fu H, Gao L, et al. BCR-ABL/GATA1/miR-138 mini circuitry contributes to the leukemogenesis of chronic myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2014;33:44–54. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albano F, Anelli L, Zagaria A, et al. Decreased TET2 gene expression during chronic myeloid leukemia progression. Leuk Res. 2011;35:e220–e222. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, et al. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 2008;18:997–1006. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gilad S, Meiri E, Yogev Y, et al. Serum microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Huang X, Yuan T, Tschannen M, et al. Characterization of human plasma-derived exosomal RNAs by deep sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:319. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-319. The authors report an applied deep sequencing to discover and characterize profiles of plasma-derived exosomal RNAs and identify the five most common miRNAs (miR-99a-5p, miR-128, miR-124-3p, miR-22-3p, and miR-99b-5p) of all mappable miRNA sequences.

- 52.Zhu S, Cao L, Zhu J, et al. Identification of maternal serum microRNAs as novel non-invasive biomarkers for prenatal detection of fetal congenital heart defects. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;424:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Franchina T, Amodeo V, Bronte G, et al. Circulating miR-22, miR-24 and miR-34a as novel predictive biomarkers to pemetrexed-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:97–99. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bader AG. miR-34 - a microRNA replacement therapy is headed to the clinic. Front Genet. 2012;3:120. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ling H, Fabbri M, Calin GA. MicroRNAs and other non-coding RNAs as targets for anticancer drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:847–865. doi: 10.1038/nrd4140. This review summarizes the roles of miRNAs and long non-coding (lnc)RNAs in cancer and discusses the current strategies in designing ncRNA-targeting therapeutics, as well as the associated challenges.

- 56.Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer cell. 2010;18:553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, et al. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer cell. 2011;19:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rohle D, Popovici-Muller J, Palaskas N, et al. An inhibitor of mutant IDH1 delays growth and promotes differentiation of glioma cells. Science. 2013;340:626–630. doi: 10.1126/science.1236062. The authors identify a selective IDH1 mutant (R132H) inhibitor, AGI-5198, through a high-throughput screen that blocks growth and promotes differentiation of glioma cells.