Abstract

Background

Liver transection is considered a critical factor influencing intra-operative blood loss. A increase in the number of complex liver resections has determined a growing interest in new devices able to ‘optimize’ the liver transection. The aim of this randomized controlled study was to compare a radiofrequency vessel-sealing system with the ‘gold-standard’ clamp-crushing technique.

Methods

From January to December 2012, 100 consecutive patients undergoing a liver resection were randomized to the radiofrequency vessel-sealing system (LF1212 group; N = 50) or to the clamp-crushing technique (Kelly group, N = 50).

Results

Background characteristics of the two groups were similar. There were not significant differences between the two groups in terms of blood loss, transection time and transection speed. In spite of a not-significant larger transection area in the LF1212 group compared with the Kelly group (51.5 versus 39 cm2, P = 0.116), the overall and ‘per cm2’ blood losses were similar whereas the transection speed was better (even if not significantly) in the LF1212 group compared with the Kelly group (1.1 cm2/min versus 0.8, P = 0.089). Mortality, morbidity and bile leak rates were similar in both groups.

Conclusions

The radiofrequency vessel-sealing system allows a quick and safe liver transection similar to the gold-standard clamp-crushing technique.

Introduction

Excessive blood loss during a liver transection and the need for blood transfusions have been shown to be correlated with higher morbidity and mortality rates and with a worse long-term outcome.1 Hepatic pedicle clamping and maintenance of a low central venous pressure during a liver transection are commonly used procedures in order to minimize the blood loss.2,3 The technique of a liver transection is considered another critical factor influencing intra-operative blood loss. Randomized studies comparing the clamp-crushing technique with other techniques [Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator (CUSA), the hydrojet dissector and the radiofrequency dissecting sealer (RFDS)] have shown that the clamp-crushing technique, usually associated with hepatic pedicle clamping, resulted either in similar or lower blood loss and transfusion requirements.4–6 Thereafter, the clamp-crushing technique associated with bipolar humid coagulation is generally considered to represent the reference standard against which new methods must be compared.7

Over the years, there has been an increasing extension of the indications for hepatic resection and in the use of pre-operative chemotherapy. The progressive increase in the rate of complex hepatic resections on a liver damaged by pre-operative chemotherapy has determined a growing interest in new devices able to shorten the transection time, to facilitate bloodless transections even without hepatic pedicle clamping and to reduce bile leak.8

The Ligasurerrrr™ Small Jaw Instrument (LF1212) (Covidien, Boulder, CO, USA) is a vessel sealing system that can fuse vessels, up to and including 7 mm, lymphatics and tissue bundles. The LF1212 device has a Kelly shape that allows accurate liver crushing in the standard fashion of the ‘classic’ clamp-crushing technique. Moreover, some data seem to suggest that this type of vessel sealing system may reduce the risk of bile leakage.9

The aim of this randomized controlled trial was to identify the most safe and efficient device in terms of overall and ‘per cm2’ blood loss during a liver transection and in terms of transection time and speed.

Materials and methods

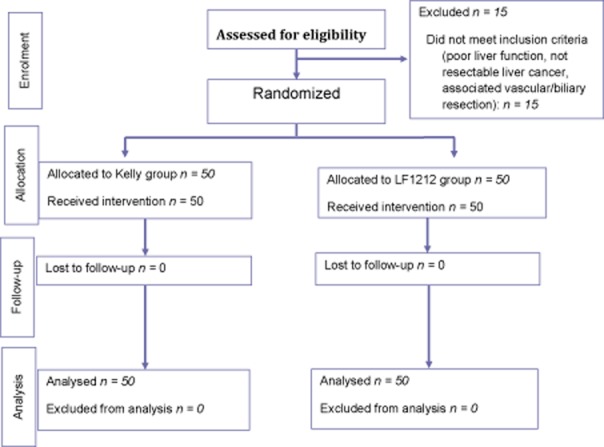

At the Department of Surgical Oncology, Institute for Cancer Research and Treament (IRCC) and at the Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery and Liver Transplantation Unit, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena (Italy), from January to December 2012, all patients considered for a curative liver resection were enrolled in this study, after giving written informed consent. A total of 100 consecutive patients whose liver tumours appeared resectable on intra-operative ultrasonography were randomly assigned to undergo a liver transection using kellyclasia plus humid bipolar coagulation (Kelly group: 50 patients) or the Ligasurerrrr™ Small Jaw Instrument (Covidien) (LF1212 group: 50 patients) by the surgeon (Fig. 1). There were 62 men, and the median (range) age was 64.7 (32.5–84.8) years.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart of a liver resection using Kellyclasia plus humid bipolar coagulation (Kelly group) versus by Ligasurerrrr™ Small Jaw Instrument (Covidien) (LF1212 group)

Randomization took place in the operating room after a laparotomy, when the patients were deemed resectable. Patients not eligible for a liver resection after a laparotomy were excluded from the study. Patients were assigned to treatment at the ratio of 1:1 according to a computer-generated randomization list by means of STATA software (version 10 ©; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Randomization was restricted by blocking with randomly varying block size and stratified by centre.

Study design

The procedure was approved by the ethical committee of the hospital.

Eligibility criteria included a liver resection either for benign or malignant tumours, ‘good hepatic function’ defined as Child–Pugh class A and a ICG Test ≤15%, an acceptable clotting profile (platelet count 90 × 103), and adequate cardio-respiratory and renal function. Patients requiring a bile duct resection, vascular resection or undergoing emergency liver surgery were excluded from the study.

Liver transection time and blood loss were calculated from the beginning to the end of the liver resection. The amount of blood loss was measured from the volume of blood in the suction container and from the weight of the soaked gauzes. At the end of liver resection, the area of the transection surface was measured: the transection surface was marked on a piece of transparent plastic sheet and then transcribed to a piece of paper containing marks of square millimeter for the measurement of the area of the liver transection surface.

In the Kelly group, transection of the liver parenchyma was performed using a Kelly clamp. Small vessels or bile ducts were mainly controlled by absorbable clips. In the LF1212 group, transection of the liver parenchyma was performed using the Ligasure device; small vessels or bile ducts up to 7 mm were mainly controlled by the Ligasure vessel sealing system.

The application of topical haemostatic agents to the raw surface of the liver at the end of the transection was not allowed unless there was occurrence of persistent bleeding which could not be controlled otherwise. In this case a topical haemostatic matrix (Floseal; Baxter Biosurgery, Deerfield, IL, USA) was used.

A bile duct fistula was defined according to the definition of the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS).10 Bilirubin levels of the drainage liquid were routinely measured on days 3 and 5 after surgery. Liver failure was defined according to the ISGLS definition11

According to the histological examination of the non-tumoural liver, the parenchyma was defined as normal in the absence of any sign of chemotherapy-induced hepatic injury, chronic liver disease or cirrhosis.12,13

The primary end-point was to the overall and ‘per cm2’ blood loss during the liver transection.

Secondary outcomes were transection time, transection speed (calculated as transection area divided by transection time, cm2/min), width of the resection margin, transfusion rate and bile leak rate.

Surgical procedure

All operations were performed by two surgeons who were equally skilled in both liver transection techniques. All resections were performed under a central venous pressure (CVP) of 5 cmH2O or less evaluated using a transducer connected to the CVP catheter.

Hepatic pedicle clamping during liver transection was not performed unless the haemorrhage could not otherwise be controlled. In this setting, hepatic pedicle clamping was always intermittent (15 min of clamping and 5 min of release).

Intra-operative ultrasonography was routinely used to guide the transection line.

A major hepatic resection was defined as a resection of three or more contiguous segments.

Statistical analysis

According to previous published data, the sample size calculation was performed with the expectation of a 30–50% difference in overall and ‘per cm2’ blood loss during a liver resection with a level of statistical significance of 0.05 and a power of 0.80.4–7 The accrual target was set at 50 patients for each group.

Results were expressed as median (range). Continuous variables were compared using the most appropriate non-parametric tests test; categorical variables were compared using the χ2 of Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. The analysis was performed in ‘an intention-to-treat’ manner. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.050.

All analyses were performed using statistical software (Statisticarrrr™ for Windows; StatSoft Italia, Vigonza, Padova, Italy).

Results

Background characteristic

Background characteristics of the two groups are reported in Table 1. The median number of liver tumours was 2 in the Kelly group compared with 2.9 in the LF1212 group (P = 0.792). Liver metastases from colorectal cancer were the most common indication to hepatic resection: overall, 73% of these patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy, usually oxaliplatin based.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of the 100 patients undergoing a liver resection using Kellyclasia (Kelly group) or the Ligasure Small Jaw Instrument (LF1212 group)

| Factors | Kelly group (n = 50) | LF1212 group (n = 50) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.7 (39.9–84.9) | 64.3 (32.5–83.2) | 0.893 |

| Pre-operative BMI | 26.5 (16.9–35.2) | 25.2 (17.1–34.2) | 0.123 |

| Number of liver tumours | 2 (1–13) | 2.9 (1–26) | 0.792 |

| Liver tumour | |||

| CR Mets (n) | 58% (29) | 62% (31) | 0.683 |

| HCC (n) | 22% (11) | 34% (17) | 0.182 |

| Other (n) | 20% (10) | 4% (2) | 0.014 |

| Neoadj CTx (n) | 40% (20) | 48% (24) | 0.546 |

| Number cycles | 6 (3–12) | 6 (−2–12) | 0.236 |

| Pre-operative serum levels | |||

| AST | 25 (11–125) | 25.5 (11–135) | 0.491 |

| ALT | 24.5 (8–129) | 25 (9–172) | 0.937 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.6 (0.1–3.6) | 0.5 (0.2–2.4) | 0.997 |

| PT | 100% (49–147) | 95 (61–129) | 0.343 |

| ALB | 4.04 (2.4–4.5) | 4.1 (2.9–4.6) | 0.941 |

| ICG (%) | 6.7 (2.3–14.4) | 7.9 () | 0.678 |

| Normal liver (n) | 50% (25) | 36% (18) | 0.157 |

| MHR (n) | 8% (4) | 12% (6) | 0.505 |

| Wedge resections | 62% (31) | 52% (26) | 0.209 |

| Multiple resections | 46% (23) | 42% (21) | 0.420 |

| Transection surface area (cm2) | 39 (6–200) | 51.5 (8–418) | 0.116 |

BMI, body mass index; CR Mets, colo-rectal liver metastases; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; Neoadj CTx, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; AST, aspartate aminotransferase (units/l); ALT, alanine aminotransferase (units/l); PT, prothrombin time (percentage); ALB, albumin (g/dl); ICG, indocyanine green clearance test; HPC, hepatic pedicle clamping; MHR, major hepatic resection.

A major hepatic resection was an uncommon procedure: most of the patients underwent multiple wedge resections. The liver transection area was larger in the LF1212 group but the difference did not reach statistical significance.

Morbidity and mortality

The in-hospital mortality rate was 3% (n = 3). Two patients died of myocardial ischaemia and liver failure, respectively, 4 and 29 days after a right hepatectomy for colorectal metastases. The last patient died of sepsis and multiorgan failure 70 days after a left hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma associated with cirrhosis. All the patients who died postoperatively were in the LF1212 group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study outcome in the two groups of the study

| Factors | Kelly group (n = 50) | LF1212 group (n = 50) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall blood loos (ml) | 200 (0–1750) | 300 (0–3000) | 0.227 |

| Blood loss ‘per cm2’ (ml/cm2) | 5.1 (0.64.8) | 5.5 (0–27.3-) | 0.468 |

| Transection time (min) | 60 (5–200) | 60 (8–221) | 0.944 |

| Transection time ‘per cm2’ | |||

| (min/cm2) | 1.2 (0.2–6.7) | 0.9 (0.2–10) | 0.089 |

| Transection speed (cm2/ml) | 0.8 (02–5.4) | 1.1 (0.1–5.5) | 0.089 |

| Transfusion rate | 26% (n = 13) | 32% (n = 16) | 0.659 |

| Hepatic pedicle clamping | 26% (n = 13) | 42% (n = 21) | 0.069 |

| Clamping time | 26 (7–68) | 15 (4–48) | 0.033 |

| Mortality | 0% (n = 0) | 6% (n = 3) | 0.121 |

| Morbidity | 34% (n = 17) | 36% (18) | 0.500 |

| Bile leak rate | 12% (n = 6) | 18% (n = 9) | 0.576 |

| Bil drainage day 3 (mg/dl) | 1.3 (0.5–50) | 1.3 (0.5–24) | 0.403 |

| Bil drainage day 5 (mg/dl) | 1 (0.3–22.8) | 1.4 (0–31.8) | 0.093 |

| Resection margin width (mm) | 6 (0–30) | 6 (0–20) | 0.516 |

| Resection margin 0 mm | 7 (14%) | 8 (16%) | 0.500 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 7 (4–24) | 8 (4–52) | 0.789 |

ml, millilitres; min, minutes; bil, bilirubin; mm, millimetres.

Thirty-five patients (35%) had post-operative complications. Overall, 15 patients developed a bile duct fistula: type A in 7 patients, type B in 7 patients and type C in 1 patient. According to the ISGLS definition, only one patient developed post-hepatectomy liver failure.11

Study outcome

Statistical analyses revealed no significant differences between the two groups of the study in terms of overall and ‘per cm2’ blood loss, transection time, transection speed, transfusion rate, bile leak rate and resection margin width. In particular, the overall and ‘per cm2’ blood losses were similar in the two groups of the study whereas there was a tendency towards a higher transection speed in the LF1212 group: 0.8 cm2/ml versus 1.1 in the Kelly group (P = 0.089).

At final pathological analysis, the median width of the resection margin was 6 mm in both groups of the study. The rate of a positive (0 mm) resection margin was similar in the two groups.

Discussion

Blood loss is one of the most important factors affecting the short- and long-term outcome of patients undergoing a liver resection.1,14 Among the ‘technical factors’ influencing intra-operative blood loss, a liver transection is considered a critical factor. Since the first report of five hepatic resections performed using the clamp-crushing technique, this technique has become the gold-standard form of liver parenchymal transection.7,15 However, in the past 10–15 years, a number of surgical devices have been created for this purpose, i.e. CUSA, bipolar sealing devices and vascular staplers. Many non-randomized studies have evaluated various techniques for liver transection claiming superiority of one method over another.16–18 The few published randomized studies have failed to show any significant advantage of one of the new transection methods over the clamp-crushing technique.15 Lesurtel's trial, which compared four different techniques of liver transection [(clamp-crushing technique versus CUSA versus Hydrojet versus dissecting sealer using radiofrequency energy (Tissuelink, Dover, NH)] showed the superiority of the clamp-crushing technique.5 However the use of hepatic pedicle clamping only in the clamp-crushing cohort may have produced a bias. The LF1212 device is a vessel sealing/divider system which seals vessels up to 7 mm, lymphatics and tissue bundles. The LF1212 forceps allow liver parenchymal transection in a similar manner to the clamp-crushing technique. To our knowledge, the present randomized study is the first one to evaluate the impact of the LF1212 device during liver transection. In the present series, the LF1212 device was demonstrated to be a safe, effective and efficient method for hepatic parenchymal transection even if compared with the ‘gold-standard’ clamp-crushing technique. In 2009, a randomized study compared the clamp-crushing technique with a vessel sealing system (Ligasure Preciserrrr™; Valleylab, Boulder, CO, USA) similar to the one used in the present study except for the absence of the cutting knife and the use of an older less efficient energy platform.19 In both arms of the study, transection of the liver was performed by Kellyclasia: the only difference was the sealing of vessels and ducts smaller than 2 mm by the vessel sealing device in the Ligasure arm whereas vessels and ducts larger than 2 mm were tied and divided. In the present study, the transection of the liver parenchyma in the LF1212 group was performed using the forceps of the vessel sealing device which was used to seal and divide vessels and ducts up to 7 mm.

A drawback of the use of the LF1212 vessel sealing system is the higher cost of each device as compared with the clamp-crushing technique. However, in our practice the use of the LF1212 device has dramatically reduced the need of costly absorbable clips during liver transection.

In the present series, the overall bile leakage rate was 15%, higher than reported in a recent French series but similar to reported by the Makuuchi group.19,20 Most of the patients underwent extended and complex wedge resections with a large residual surface area at the end of the liver transection (median transection surface area 50 cm2, data not shown). Moreover, half of these patients had type A fistulae which did not require any further treatment. Some concerns have been raised regarding the effectiveness of the vessel sealing system in preventing bile leaks after a liver resection.21 In the present prospective randomized study, the bile leakage rate was not statistically different between the two groups of the study. Of note, our sample size was not calculated to identify a difference in bile leaks. However, adequate sealing of the intrahepatic bile ducts by the Ligasure vessel sealing system was recently confirmed at the histolgical analyses of the transected liver parenchyma.9 Moreover, as the lateral thermal spread of the Ligasure device is minimal (1 mm) if compared with, i.e. harmonic scalpel, the LF1212 device can be used close to the hepatic hilum structures or to the hepatic vein confluence.5

In 2006, a randomized study clearly showed that a liver resection without hepatic pedicle clamping was safe.2 Since then, we have performed most of the liver resections without using the hepatic pedicle clamping. In the present study, unlike the Lesurtel's study, hepatic pedicle clamping was not allowed in both groups of randomization unless the occurrence of a bleed which could not be controlled otherwise.5 Overall, about one-third of the patients required hepatic pedicle clamping with a median clamping time of 23 min. The increased rate of hepatic pedicle clamping in the LF1212 group may be explained by a less effective sealing power on the branches of the hepatic veins. In fact, the vessel sealing technology of the LF1212 works by determining the fusion of the connective tissue present in the vessel wall. Thereafter, as the wall of the hepatic veins is thin with less connective tissue than the portal or arterial branches and the vessel sealing may be less effective thus increasing the risk of back-flow bleeding, hepatic pedicle clamping may be used more frequently when working close to the hepatic vein confluence. However, the median clamping time in the LF1212 group was short (15 min). Clamping times shorter than 40 min are associated with minimal cellular injury.22

The frequent use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and the tendency to resect multiple, bilateral liver metastases have increased both the risk and the ‘need’ to have narrow resection margins. However, although a positive resection margin increases the risk of margin recurrence, the tumour biology and not the width of the resection margin affects the long-term outcome.23,24 In the present series, only 15% of the patients had a positive resection margin, in spite of the mean number of resected colorectal liver metastases being high (n = 4, data not shown). The technique of liver resection did not impact on the width of the resection margins. The results of the present study compares favourably with those shown by a French study reporting a 24% rate of positive resection margins.25

The accrual target set at 50 patients for each group was large enough to detect a 30–50% difference in blood loss during liver transection. However, as very few studies have been published that evaluate the vessel-sealing system technique during liver transection, it might be that the reported difference was too high and, thereafter, the ‘50 patients per-group’ target too low to detect significant differences in terms of blood loss.

In conclusion, a liver resection with the Ligasurerrrr™ Small Jaw Instrument is associated with similar results in terms of blood loss, transection speed and bile leak rate compared with the conventional clamp-crushing technique. However, the Kelly shape of the Ligasure device which allows accurate and safe liver crushing similar to the ‘classic’ clamp-crushing technique may increase the surgeon's ‘comfort’ which is difficult to measure but critically important for the completion of a liver resection.

Conflicts of interest

The authors confirm no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kooby DA, Stockmann J, Ben-Porat L, Gonen M, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo RP, et al. Influence of transfusions on perioperative and long-term outcome in patients following hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2003;237:860–869. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000072371.95588.DA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capussotti L, Muratore A, Ferrero A, Massucco P, Ribero D, Polastri R. Randomized clinical trial of liver resection with and without hepatic pedicle clamping. Br J Surg. 2006;93:685–689. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melendez JA, Arslan V, Fisher ME, Wuest D, Jarnaging WR, Fong Y, et al. Perioperative outcomes of major hepatic resections under low central venous pressure anesthesia: blood loss, blood transfusion, and the risk of postoperative renal dysfunction. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:620–625. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koo BN, Kil HK, Choi JS, Kim JY, Chun DH, Hong YW. Hepatic resection by the Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator increases the incidence and severity of veous air embolism. Anesth Anal. 2005;101:966–970. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000169295.08054.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lesurtel M, Selzner M, Petrowsky H, McCormack L, Clavien P. How should transection of the liver be performed? A prospective randomized study in 100 consecutive patients: comparing four different transection strategies. Ann Surg. 2005;242:814–823. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000189121.35617.d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takayama T, Makuuchi M, Kubota K, Harihara Y, Hui AM, Sano K, et al. Randomized comparison of ultrasonic vs clamp transection of the liver. Arch Surg. 2001;136:922–928. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.8.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pamecha V, Gurusamy KS, Sharma D, Davidson BR. Techniques for liver parenchymal transection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. HPB. 2009;11:275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman W. No silver bullet in liver transection. What has 35 years of new technology added to liver surgery? Ann Surg. 2009;250:2004–2205. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b6df4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romano F, Garancini M, Caprotti R, Bovo G, Conti M, Perego E, et al. Hepatic resection using a bipolar vessel sealing device: technical and histological analysis. HPB. 2007;9:339–344. doi: 10.1080/13651820701504181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch M, Garden J, Padbury R, Rahbari NN, Adam R, Capussotti L, et al. Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a definition and grading of severity by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery. Surgery. 2011;149:680–688. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahbari NN, Garden J, Padbury R, Brooke-Smith M, Crawford M, Adam R, et al. Posthepatectomy liver failure: a definition and grading by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS) Surgery. 2011;149:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vauthey JN, Pawlik TM, Ribero D, Wu TT, Zorzi D, Hoff PM, et al. Chemotherapy regimen predicts steatohepatitis and an increase in 90-day mortality after surgery for hepatic colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2065–2072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, et al. Histological grading and staging of crhonic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–699. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz SC, Shia J, Liau KH, Gonen M, Ruo L, Jarnaging WR, et al. Operative blood loss independently predicts recurrence and survival after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;249:617–623. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819ed22f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin TY. A simplified technique for hepatic resection: the crush method. Ann Surg. 1974;180:285–290. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197409000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aloia TA, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN. Two-surgeon technique for hepatic parenchymal transection of the noncirrhotic liver using saline-linked cautery and ultrasonic dissection. Ann Surg. 2005;242:172–177. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171300.62318.f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castaldo ET, Earl TM, Chari RS, Gorden DL, Merchant NB, Wright JK, et al. A clinical comparative analysis of crush/clam, stapler, and dissecting sealer hepatic transection methods. HPB. 2008;10:321–326. doi: 10.1080/13651820802320040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porembka MR, Doyle MBM, Hamilton NA, Steven POS, Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, et al. Utility of the Gyrus open forceps in hepatic parenchymal transection. HPB. 2009;11:258–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikeda M, Hasegawa K, Sano K, Imamura H, Beck Y, Sugawara Y, et al. The vessel sealing system (Ligasure) in hepatic resection. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2009;250:199–203. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a334f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillaud A, Pery C, Campillo B, Lourdais A, Laurent S, Boudjema K. Incidence and predictive factors of clinically relevant bile leakage in the modern era of liver resections. HPB. 2013;15:224–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews BD, Backus CL, Kercher KW, Mostafa G, Lentzner A, et al. Effectiveness of the ultrasonic coagulating shears, Ligasure vessel sealer, and surgical clip application in biliary surgery: a comparative analysis. Am Surg. 2001;67:901–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muratore A, Ribero D, Ferrero A, Bergero R, Capussotti L. Prospective randomized study of steroids in the prevention of ischemic injury during hepatic resection with pedicle clamping. Br J Surg. 2003;90:17–22. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muratore A, Ribero D, Zimmitti G, Mellano A, Langella S, Capussotti L. Resection margin and recurrence-free survival aftr liver resection of colorectal metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1324–1329. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0770-4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0770-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pawlik TM, Scoggins CR, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK, Andres A, Eng C, et al. Effect of surgical margin status on survival and site of recurrence after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2005;241:715–724. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000160703.75808.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Haas RJ, Wicherts DA, Flores E, Azoulay D, Castaing D, Adam R. R1 resection by necessity for colorectal liver metastases. Is it still a contraindication to surgery? Ann Surg. 2008;248:626–637. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818a07f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]