Abstract

Objectives

The optimal strategy for the reconstruction of the pancreas following pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is still debated. The aim of this study was to compare the outcomes of isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy (IRPJ) with those of pancreaticogastrostomy (PG) after PD.

Methods

Consecutive patients submitted to PD were randomized to either method of reconstruction. The primary outcome measure was the rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF). Secondary outcomes included operative time, day to resumption of oral feeding, postoperative morbidity and mortality, and exocrine and endocrine pancreatic functions.

Results

Ninety patients treated by PD were included in the study. The median total operative time was significantly longer in the IRPJ group (320 min versus 300 min; P = 0.047). Postoperative pancreatic fistula developed in nine of 45 patients in the IRPJ group and 10 of 45 patients in the PG group (P = 0.796). Seven IRPJ patients and four PG patients had POPF of type B or C (P = 0.710). Time to resumption of oral feeding was shorter in the IRPJ group (P = 0.03). Steatorrhea at 1 year was reported in nine of 42 IRPJ patients and 18 of 41 PG patients (P = 0.029). Albumin levels at 1 year were 3.6 g/dl in the IRPJ group and 3.3 g/dl in the PG group (P = 0.001).

Conclusions

Isolated Roux loop PJ was not associated with a lower rate of POPF, but was associated with a decrease in the incidence of postoperative steatorrhea. The technique allowed for early oral feeding and the maintenance of oral feeding even if POPF developed.

Introduction

Although operative mortality in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) has fallen to <5%, incidences of postoperative morbidity remain high at 40–50%.1–4 The occurrence of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) remains challenging, even at high-volume centres, and contributes significantly to increases in hospital stay, costs and mortality. Intra-abdominal collection, delayed gastric emptying, postoperative haemorrhage and sepsis are common sequelae of pancreatic leakage.3–5 Incidences of POPF after PD range from 5% to 30%.3–7

Many technical modifications of the pancreatic anastomosis have been proposed and evaluated in attempts to prevent POPF. The best type of pancreatic reconstruction and anastomotic technique are still debated.2,4–6 The two most common methods of pancreatic anastomosis are pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) and pancreaticogastrostomy (PG). Comparisons of the short-term outcomes of these two methods of reconstruction show mixed results.2–5,8–10 Longterm outcomes, including morphological outcomes and exocrine and endocrine functions of the remaining pancreas, have yet to be determined.9,11–13

The concept of isolated Roux loop PJ (IRPJ) is based on the theory that reducing the activation of pancreatic juice by biliary secretion will decrease the incidence and severity of POPF.14–17 Recent prospective randomized studies have compared the outcomes of IRPJ with those of conventional PJ,14–17 but not with those of PG.

Hence, the purpose of this study was to compare the outcomes of IRPJ with those of PG after PD with regard to the rate of occurrence of POPF, postoperative morbidity and mortality, and exocrine and endocrine pancreatic functions in a prospective randomized study.

Materials and methods

Patients

Consecutive patients undergoing PD for periampullary tumours at the Gastroenterology Surgical Centre, Mansoura, Egypt, during the period from January 2011 to May 2013 were eligible for the study. Exclusion criteria denied the inclusion of patients with locally advanced periampullary tumours or metastases, patients undergoing bilioenteric or gastroenteric bypass or total pancreatectomy, and patients with advanced liver cirrhosis (Child–Pugh class B or C) with portal hypertension, malnutrition or coagulopathy.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study after the nature of the disease and possible treatments and potential complications had been carefully explained. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed in patients with serum bilirubin levels of >10 mg/dl or when biliary obstruction was associated with high liver enzymes (more than three-fold the normal level (i.e. >120 IU/ml).4

Randomization

Patients enrolled in the study were randomized into two groups using the closed envelope method. Envelopes were drawn and opened by a nurse not otherwise engaged in the study in the operating room after resection. Patients in one group underwent IRPJ with isolated pancreatic drainage and patients in the other underwent PG. No patient was excluded after resection of the tumour. The same surgeons, who had equivalent levels of expertise, performed PD in both groups.

Operative techniques

Standard PD was performed after the pancreatic head and duodenum had been mobilized. The pancreas was divided anteriorly and to the left of the superior mesenteric vein and portal vein. Antrectomy was performed in all patients.

Isolated Roux loop PJ group

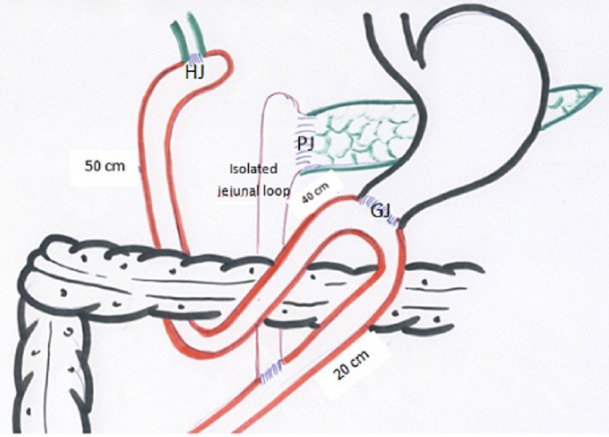

Pancreaticojejunostomy was constructed in two layers after the performance of a small jejunostomy in the isolated jejunal loop equal to the diameter of the pancreatic duct. The duct and the entire thickness of the pancreatic parenchyma were sutured to the full thickness of the jejunum using 5/0 vicryl interrupted sutures in a radial manner and 3/0 silk interrupted sutures to attach the outer seromuscular layer to the pancreatic capsule without pancreatic stenting. A separate Roux loop was created for the end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) and the end-to-side antecolic gastrojejunostomy (GJ). The PJ loop was anastomosed to the main loop (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) carried out using a 40-cm isolated loop of jejunum for PJ, and a Roux loop for hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) and gastrojejunostomy (GJ) (50 cm caudal to the HJ). The PJ loop was anastomosed to the main loop (20 cm caudal to the GJ)

Pancreaticogastrostomy group

The proximal part of the pancreatic remnant was mobilized from the splenic vessels and the retroperitoneum for subsequent anastomosis to the posterior gastric wall. The PG was constructed in two layers. A seromuscular suture was performed between the posterior wall of the stomach and pancreatic capsule using either interrupted or continuous 3/0 silk. A 2.5–3.0-cm gastrostomy was performed and the pancreatic parenchyma with the duct were sutured to the full thickness of the stomach using interrupted or continuous 5/0 vicryl sutures. The outer seromuscular layer between the stomach and pancreatic capsule was sutured using 3/0 silk interrupted sutures without pancreatic stenting.

Biliary drainage was achieved by end-to-side HJ (retrocolic). Gastric drainage was achieved by an antecolic end-to-side GJ 30 cm caudal to the HJ.

Postoperative management

All patients were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for at least 1 day before transfer to the ward. Octreotide was given to all patients routinely for 4 days. Outputs from operatively placed drains and nasogastric tubes were recorded daily. Patients resumed oral feeding on a fluid diet followed by a regular diet once bowel sounds were present and patients were able to tolerate oral feeding.

Serum and drainage fluid amylase was measured on postoperative days (PoDs) 1 and 5. Abdominal ultrasound was performed routinely in all patients. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage was performed in patients who demonstrated an abdominal collection.

Follow-up was conducted at 1 week, 3 months and 6 months postoperatively, and then at 1 year. Patients were also seen at outpatient clinics if symptoms developed between follow-up visits.

Assessments

The primary outcome was the rate of POPF. Postoperative pancreatic fistula was defined according to the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) definition as any measurable volume of fluid on or after PoD 3 with amylase content greater than three times serum amylase activity.18,19 The severity of POPF was assessed using the Dindo–Clavien system of classification as Grade I (no need for specific intervention), Grade II (need for drug therapy such as antibiotics, blood transfusion, total parenteral nutrition), Grades IIIa and IIIb (need for invasive radiological, endoscopic or surgical therapy), Grades IVa and IVb (organ dysfunction requiring an ICU stay and management), and Grade V (death).20 Complications of severity higher than Clavien–Dindo Grade III were considered to be major complications. Pancreatic fistulae were graded according to ISGPF criteria into Grades A, B and C according to their clinical course.18,19

Secondary outcomes included total operative time, operative time for reconstruction, length of postoperative stay, postoperative complications (including delayed gastric emptying, biliary leakage, bleeding PG, bleeding GJ, internal haemorrhage and pulmonary complications), endocrine and exocrine functions, need for re-exploration, and survival rate. Biliary leak was defined according to ISGPF criteria as the presence of bile in drainage fluid persisting to PoD 4. Delayed gastric emptying was defined as output from a nasogastric tube of >500 ml per day persisting beyond PoD 10, failure to maintain oral intake by PoD 14, or need for the reinsertion of a nasogastric tube.18,19

Complications were graded according to severity on a validated 5-point scale using the Dindo–Clavien complication classification system into Grades I, II, IIIa and IIIb, IVa and IVb, and V.20

To assess endocrine function, fasting blood glucose level was measured without the administration of oral hypoglycaemic drugs or insulin (normal level: <110 mg/dl). Any diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (DM) was based on criteria established by the World Health Organization study group on DM.21

Pancreatic exocrine function was evaluated. Patients who were taking pancreatic enzyme supplements were asked to stop this treatment at least 10 days before the clinical evaluation. Patients were asked about the presence of steatorrhea (more than three stools per day, faecal output of >200 g/day for at least 3 days, pale or yellow stools, and stools with a pasty or greasy appearance). Severe steatorrhea was defined by the presence of at least three of these criteria, need for pancreatic enzyme supplements, and pre- and postoperative variation in body weight.22

Data collected

Preoperative and intraoperative variables included patient demographics, liver status, tumour size, pancreatic duct diameter, texture of the pancreas, operative time, blood loss and blood transfusion.

Postoperative variables included postoperative complications, drain output and nature, drain amylase, liver function, days to resumption of oral feeding, postoperative stay, re-exploration, hospital mortality, postoperative pathology, fasting blood sugar at 1 year, postoperative weight compared with preoperative weight, and presence or absence of steatorrhea.

A sample size for each group was calculated to set the level of power for the study at 80% with a 5% significance level supposing POPF rates of 17% after PG4–6 and 0% after IRPJ.14–16 Based on these parameters, a sample size of 45 subjects in each group was deemed to be sufficient.

Statistical analysis in this study was performed using spss Version 17 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were analysed on an intension-to-treat basis. For continuous variables, descriptive statistics were calculated and described as medians and ranges. Categorical variables were reported using percentages of the total number of patients (n = 90) and of the number of patients in each group (n = 45). Student's t-test was used to detect differences in the means of continuous variables. The chi-squared test was used for categorical variables. P-values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Significance was two-tailed.

Results

Patient characteristics

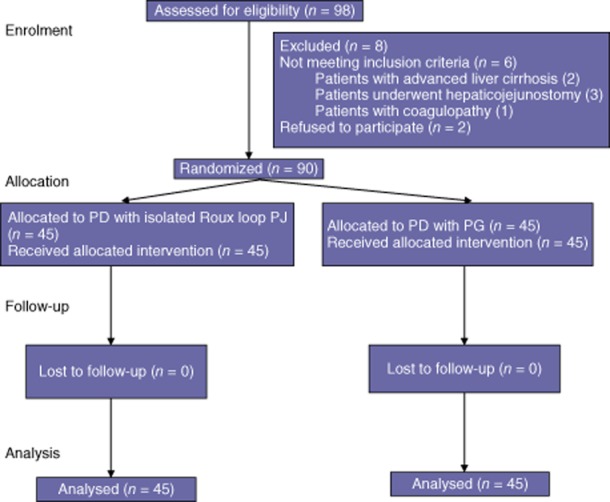

The study flow chart is shown in Fig. 2. The characteristics of the two randomized groups are presented in Table 1. Intraoperative data are shown in Table 2. Postoperative data are shown in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram showing progress through the phases of this randomized trial (i.e. enrolment, intervention allocation, follow-up and data analysis). PD, pancreaticoduodenectomy; PG, pancreaticogastrostomy; PJ, pancreaticojejunostomy

Table 1.

Demographic data for patients submitted to isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy (IRPJ) or pancreaticogastrostomy (PG)

| Variable | All patients | IRPJ group | PG group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 90) | (n = 45) | (n = 45) | ||

| Patient age, years, median (range) | 55.5 (12–73) | 54 (15–73) | 58 (12–73) | 0.105 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 40 (44.4%) | 18 | 22 | 0.396 |

| Male | 50 (55.6%) | 27 | 23 | |

| Symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Jaundice | 83 (92.2%) | 41 | 42 | 0.694 |

| Abdominal pain | 69 (76.7%) | 34 | 35 | 0.803 |

| Loss of weight | 19 (21.1%) | 12 | 7 | 0.197 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, median (range) | 21 (17–34) | 21 (17–34) | 22 (17–32) | 0.321 |

| Preoperative bilirubin, mg/dl, median (range) | 3.2 (0.4–36.0) | 4.4 (0.5–25.7) | 2.7 (0.4–36.0) | 0.325 |

| Preoperative biliary drainage (ERCP), n (%) | 54 (60.0%) | 23 | 31 | 0.089 |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Table 2.

Operative data for patients submitted to isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy (IRPJ) or pancreaticogastrostomy (PG)

| Variable | All patients | IRPJ group | PG group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 90) | (n = 45) | (n = 45) | ||

| Cirrhotic liver, n (%) | 12 (13.3%) | 7 | 5 | 0.535 |

| Size of mass, cm, median (range) | 2 (0.5–6.0) | 2 (0.5–6.0 cm) | 3 (1.0–4.0) | 0.477 |

| <2 cm, n (%) | 46 (51.5%) | 26 | 20 | 0.206 |

| >2 cm, n (%) | 44 (48.5%) | 19 | 25 | |

| Ampullary site, n (%) | 36 (40.0%) | 19 | 17 | |

| Pancreatic head mass | 46 (51.1%) | 20 | 26 | 0.313 |

| Duodenal tumour | 6 (6.7%) | 4 | 2 | |

| Lower CBD tumour | 2 (2.2%) | 2 | 0 | |

| Indication for resection, n (%) | ||||

| Malignant | 75 (83.4%) | 38 | 37 | 0.466 |

| Benign | 13 (14.4%) | 6 | 7 | |

| Borderline | 2 (2.2%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Pancreatic duct diameter, mm, median (range) | 3.5 (1–12) | 3 (1–12) | 4 (2–10) | 0.632 |

| <3 mm, n (%) | 43 (47.8%) | 21 | 22 | 0.833 |

| >3 mm, n (%) | 47 (52.2%) | 24 | 23 | |

| Pancreatic duct to posterior border, mm, median (range) | 3 (1–15) | 3 (1–15) | 3 (1–15) | 0.537 |

| <3 mm, n (%) | 46 (51.1%) | 23 | 23 | 1 |

| >3 mm, n (%) | 44 (48.9%) | 22 | 22 | |

| Pancreatic consistency, n (%) | ||||

| Firm | 42 (46.7%) | 23 | 19 | 0.398 |

| Soft | 48 (53.3%) | 22 | 26 | |

| Pancreatic remnant mobilization, cm, median (range) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.039 |

| Total operative time, min, median (range) | 300 (210–480) | 320 (240–480) | 300 (210–420) | 0.047 |

| Operative time for reconstruction, min, median (range) | 110 (90–125) | 115 (95–125) | 100 (90–120) | <0.001 |

| Blood loss, ml, median (range) | 500 (50–3000) | 500 (50–2500) | 400 (100–3000) | 0.732 |

CBD, common bile duct.

Table 3.

Postoperative data for patients submitted to isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy (IRPJ) or pancreaticogastrostomy (PG)

| Variable | All patients | IRPJ group | PG group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 90) | (n = 45) | (n = 45) | ||

| Hospital stay, days, median (range) | 8 (4–41) | 8 (5–41) | 9 (4–34) | 0.448 |

| Time to drain removal, days, median (range) | 8 (4–35) | 7.5 (5–35) | 9 (4–34) | 0.118 |

| Amount of draining, ml, median (range) | 900 (65–17000) | 850 (70–15000) | 950 (65–17000) | 0.705 |

| Time to oral feeding, days, median (range) | 6 (4–30) | 5 (4–20) | 6 (4–30) | 0.029 |

| Patients with complications, n (%) | 31 (34.4%) | 14 | 17 | 0.506 |

| Complication grade, n (%) | ||||

| I | 3 (3.3%) | 2 | 1 | 0.724 |

| II | 10 (11.1%) | 5 | 5 | |

| IIIa | 5 (5.6%) | 2 | 3 | |

| IIIb | 6 (6.7%) | 2 | 4 | |

| IV | 7 (7.8%) | 3 | 4 | |

| V | 7 (7.8%) | 3 | 4 | |

| Severity of complications, n (%) | ||||

| Minor (<IIIb) | 14 (15.5%) | 8 | 6 | 0.385 |

| Major (>IIIb) | 17 (18.9%) | 6 | 11 | |

| Pancreatic leakage (POPF), n (%) | 19 (21.1%) | 9 | 10 | 0.796 |

| POPF Grade A, n (%) | 8 (8.9%) | 5 | 3 | 0.710 |

| POPF Grade B, n (%) | 5 (5.6%) | 2 | 3 | |

| POPF Grade C, n (%) | 6 (6.7%) | 2 | 4 | |

| Pancreatitis, n (%) | 3 (3.3%) | 2 | 1 | 0.557 |

| Biliary leakage, n (%) | 10 (11.1%) | 4 | 6 | 0.502 |

| Delayed gastric emptying, n (%) | 13 (14.4%) | 4 | 9 | 0.134 |

| Obstructed GJ, n (%) | 2 (2.2%) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bleeding GJ, n (%) | 2 (2.2%) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bleeding PG, n (%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0 | 2 | 0.153 |

| Internal haemorrhage, n (%) | 2 (2.2%) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Wound infection, n (%) | 5 (5.6%) | 3 | 2 | 0.645 |

| Liver failure, n (%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 | 0 | |

| Pulmonary complications, n (%) | 4 (4.4%) | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Re-exploration, n (%) | 7 (7.8%) | 3 | 4 | 0.694 |

| Readmission rate at 3 months, n (%) | 6 (6.7%) | 2 | 4 | 0.398 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 7 (7.8%) | 3 | 4 | 0.694 |

| Pulmonary embolism, n (%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 | 0 | |

| SIRS secondary to POPF, n (%) | 5 (5.6%) | 2 | 3 | |

| Liver failure, n (%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0 | 1 | |

POPF, postoperative pancreatic fistula; GJ, gastrojejunostomy; PG, pancreaticogastrostomy; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Ultrasound-guided tubal drainage to resolve an intra-abdominal collection was required in four patients in the IRPJ group and six patients in the PG group (P = 0.502).

Longterm outcomes are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Functional changes in patients submitted to isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy (IRPJ) or pancreaticogastrostomy (PG)

| Variable | IRPJ group | PG group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 45) | (n = 45) | ||

| Preoperative steatorrhea, n | 8/45 | 10/45 | 0.598 |

| Postoperative steatorrhea, n | 9/42 | 18/41 | 0.029 |

| P-value | 0.157 | 0.005 | |

| Need for pancreatic enzyme supplements, n | 9/42 | 18/41 | 0.029 |

| Preoperative albumin, g/dl, median (range) | 4 (3.2–5) | 4 (3.3–4.8) | 0.915 |

| Postoperative albumin, g/dl, median (range) | 3.6 (3.1–4.5) | 3.3 (2.5–4.1) | <0.001 |

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Preoperative weight, kg, median (range) | 71 (54–121) | 72 (54–72) | 0.596 |

| Postoperative weight, kg, median (range) | 71 (52–99) | 70 (50–105) | 0.789 |

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Preoperative body mass index, n | |||

| <25 kg/m2 | 30/45 | 26/45 | 0.384 |

| >25 kg/m2 | 15/45 | 19/45 | |

| Postoperative body mass index, n | |||

| <25 kg/m2 | 34/42 | 34/41 | 0.815 |

| >25 kg/m2 | 8/42 | 7/41 | |

| P-value | 0.025 | 0.002 | |

| Preoperative diabetes mellitus, n | 11/45 | 13/45 | 0.634 |

| Postoperative diabetes mellitus, n | 12/42 | 20/41 | 0.059 |

| P-value | 0.157 | 0.008 | |

| Preoperative fasting blood sugar, mg/dl, median (range) | 114 (71–275) | 102 (79–217) | 0.477 |

| Postoperative fasting blood sugar, mg/dl, median (range) | 102 (70–210) | 132 (90–299) | 0.022 |

| P-value | 0.004 | <0.001 | |

Discussion

The safe reconstruction of the pancreatic anatomy after PD continues to challenge pancreatic surgeons.1–3 Ideally, the reconstructive technique should not only minimize the risk for POPF, but should decrease its severity if POPF does occur and should also maintain exocrine and endocrine pancreatic functions. Pancreaticogastrostomy has several potential advantages over PJ. The PG anastomosis is technically feasible and easy to perform, and contributes towards a lower tendency for ischaemia and less tension as a result of anatomical factors. The gastric acid environment is thought to inhibit the activation of pancreatic enzymes and prevent the breakdown effect of proteolytic enzymes on the anastomosis.2,23–25

Incidences of POPF after PD using PG reconstruction range from 3% to 14.3%.4,6–10 Several studies have reported low rates of POPF after PD using IRPJ reconstruction in the range of 0–10.9%, and related decreases in morbidity and mortality15,16,26–32 (Table 5). Hence, the aim of this study was to compare the outcomes of IRPJ with those of PG after PD.

Table 5.

Results of Roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy reported in different studies

| Type of study | Patients, n | POPF, n (%) | Steatorrhea, n (%) | DGE, n (%) | Duration of surgery, median | Hospital stay, days, median | HM, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingsnorth29 | 1994 | Single group | 52 | 0 | 10/41 (24.4%) | 18 | 3 (5.8%) | ||

| Papadimitriou et al.32 | 1999 | Retrospective Single group | 105 | 0 | 7.6 | 1 (0.9%) | |||

| Khan et al.28 | 2002 | Retrospective Single group | 41 | 0 | 5 (12.2%) | 8.0 h | 16 | 1 (2.4%) | |

| Ma et al.38 | 2002 | Retrospective Single group | 26 | 0 | 1 (3.8%) | 10–14 | 0 | ||

| Sutton et al.16 | 2004 | Retrospective Single group | 61 | 0 | 5.5 h | 16 | 3 (5%) | ||

| Casadei et al.27 | 2008 | Prospective | 18 IRPJ | 2/18 (11.1%) | 2.6% | ||||

| Non-randomized | 20 CPJ | 3/20 (15%) | 26.3% | ||||||

| Grobmyer47 | 2008 | Retrospective | 112 RYR | 14.8% | 10.1% | 5.8 h | 18 | 0.9 | |

| Two group | 588 CPJ | 5.7% | 10.3% | 5.1 h | 19 | 2.6% | |||

| Kaman et al.14 | 2008 | Retrospective | 60 IRPJ | 10% | 12 (20%) | 17.5 | 5 (8%) | ||

| Two group | 51 CL | 12% | 6 (12%) | 17.25 d | 4 (8%) | ||||

| Wayne et al.37 | 2008 | Retrospective Single group | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Fragulidis et al.35 | 2009 | Retrospective | 69 LIPJ | 4.3% | 11 | 255 min | 10.2 | 1 | |

| Two groups | 63 SIPJ | 14.2% | 11 | 245 min | 16.3 | 1 | |||

| Perwaiz et al.15 | 2009 | Retrospective | 53 IRPJ | 5 (9.4%) | 5 (9.4%) | 442 min | 10.1 | 2 (3.7%) | |

| Single group | 55 CPJ | 6 (10.9%) | 4 (7.2%) | 370 min | 9.5 | 2 (3.6% | |||

| Ballas et al.36 | 2010 | Two groups | 46 IRPJ | 2 (4.3%) | 7 (15.2%) | 366.1 min | 14.6 d | 1 (2.2%) | |

| 42 CPJ | 3 (7.1%) | 4 (9.5%) | 338.8 min | 19.5 | 1(2.3%) | ||||

| Pozzo et al.48 | 2010 | Single group | 27 | 0 | 18 | ||||

| Ke et al.17 | 2013 | Prospective Randomized | 107 IRPJ | 17 (15.7%) | 25 (23%) | 5.7 h | 18.7 | 0 | |

| 109 CPJ | 19 (17.6%) | 27 (25%) | 5.6 h | 19.1 | 0 | ||||

POPF, postoperative pancreatic fistula; DGE, delayed gastric emptying; HM, hospital mortality; IRPJ, isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy; CPJ, conventional pancreaticojejunostomy; RYR-PJ, Roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy; JPJ, conventional pancreaticojejunostomy; LIPJ, long loop isolated pancreaticojejunostomy; SIPJ, short loop isolated pancreaticojejunostomy.

Isolated Roux loop PJ was first reported in 1976 by Machado et al.30 In many studies, IRPJ did not avoid POPF but did decrease leak-related morbidity and mortality.14–17 In a prospective randomized study of 216 patients, Ke et al.17 found similar rates of POPF in patients undergoing conventional loop PJ and IRPJ, but the ratio of Grade B POPF was much higher in the conventional PJ group than the IRPJ group. Other studies have reported lower leak rates and no leak-related mortality after IRPJ.16,28,29,32–38 In the current study, the isolated Roux loop did not decrease the incidence or severity of POPF.

These findings conform with those of a recently published survey conducted in Japanese centres, which revealed no difference between conventional PJ and PG in rates of POPF, bleeding, abdominal collection and mortality after pancreatic head resection in 3109 patients.39,40 All prospective randomized studies have failed to show significant differences, which suggests that PJ and PG provide equally good results.2,23,41,42

Sutton et al. have previously reported the obstruction of the distal enteroenterostomy secondary to oedema leading to luminal pressure-induced POPF as a theoretical danger of IRPJ reconstruction.16 This problem was not observed in the current study, possibly because a wide enteroenterostomy was performed in all patients.

A possible disadvantage of IRPJ is that it requires an additional enteroenterostomy, which increases operative time.14,17 Median total and reconstructive operative times in the current study were longer in the IRPJ group.

In the current study, oral feeding commenced 1 day earlier in the IRPJ group than in the PG group. Patients with POPF after IRPJ resumed oral feeding without any increase in the amount of leak and demonstrated a principal advantage in the absence of delayed gastric emptying. However, some studies have found no significant difference in either of these factors.14–17

In the current study, the frequency of severe steatorrhea at 1 year post-surgery was significantly higher in the PG than in the IRPJ group (P = 0.029). Correspondingly, median albumin at 1 year was significantly higher in the IRPJ group than in the PG group (3.6 g/dl versus 3.3 g/dl; P ≤ 0.001). Several published series have reported that exocrine function after PD depends on various complex factors, including pre-existing obstructive pancreatitis by tumour, the degree of fibrosis in the pancreatic remnant, the volume of resected pancreatic parenchyma, impairment of pancreatic juice flow as a result of anastomotic stricture or swelling of the gastric mucosa, and possibly the type of pancreatic reconstruction.13,43–46 Some retrospective studies have reported higher rates of suggested pancreatic exocrine insufficiency in patients with longterm follow-up who have undergone PG rather than PJ reconstruction.11–13,29 There is, however, no evidence that impaired pancreatic endocrine function would be associated more often with a certain type of reconstruction.43 Pancreaticogastrostomy may cause more morphological and functional derangement because the reflux of gastric juice causes the inactivation of pancreatic enzymes and early pancreatic insufficiency.11,12,22

The present study is subject to two limitations. Firstly, the sample size was calculated to set the level of power for the study at 80% with a 5% significance level, presupposing POPF rates of 17% after PG4–6 and 0% after IRPJ.14–16 The calculation of the sample size in relation to the 4–14% incidence of POPF after IRPJ15,17,36 yielded large numbers in excess of 100 patients per group, which exceeded the proposed duration of the trial. Secondly, the operations were performed by eight surgeons, which may have represented a source of bias. However, the fact that these surgeons had almost equal levels of experience within the trial helps to overcome this. Nonetheless, further prospective randomized studies with larger sample sizes are required to confirm these results.

Conclusions

The results of this study contribute to evidence indicating that IRPJ is not associated with a lower rate of POPF, but is associated with a decrease in the incidence of postoperative steatorrhea. Isolated Roux loop PJ allowed for early oral feeding and facilitated the maintenance of oral feeding even if POPF developed.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Riediger H, Makowiec F, Fischer E, Adam U, Hopt UT. Postoperative morbidity and longterm survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy with superior mesenterico-portal vein resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1106–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topal B, Fieuws S, Aerts R, Weerts J, Feryn T, Roeyen G, et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours: a multicentre randomized trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:655–662. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang YM, Tian XD, Zhuang Y, Wang WM, Wan YL, Huang YT. Risk factors of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2456–2461. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i16.2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Nakeeb A, Salah T, Sultan A, El Hemaly M, Askr W, Ezzat H, et al. Pancreatic anastomotic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Risk factors, clinical predictors, and management (single-centre experience) World J Surg. 2013;37:1405–1418. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1998-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid-Lombardo KM, Farnell MB, Crippa S, Barnett M, Maupin G, Bassi C, et al. Pancreatic Anastomotic Leak Study Group. Pancreatic anastomotic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy in11,507 patients: a report from the Pancreatic Anastomotic Leak Study Group. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1451–1458. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0270-4. discussion 1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKay A, Mackenzie S, Sutherland FR, Bathe OF, Doig C, Dort J, et al. Meta-analysis of pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93:929–936. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu F, Wang M, Wang X, Tian R, Shi C, Xu M, et al. Modified technique of pancreaticogastrostomy for soft pancreas with two continuous hemstitch sutures: a single-centre prospective study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1306–1311. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takano S, Ito Y, Watanabe Y, Yokoyama T, Kubota N, Iwai S. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy in reconstruction following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2000;87:423–427. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bock EA, Hurtuk MG, Shoup M, Aranha GV. Late complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:914–919. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1805-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wente MN, Shrikhande SV, Müller MW, Diener MK, Seiler CM, Friess H, et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2007;193:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemaire E, O'Toole D, Sauvanet A, Hammel P, Belghiti J, Ruszniewski P. Functional and morphological changes in the pancreatic remnant following pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastric anastomosis. Br J Surg. 2000;87:434–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang WL, Su CH, Shyr YM, Chen TH, Lee RC, Tai LC, et al. Functional and morphological changes in pancreatic remnant after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Pancreas. 2007;35:361–365. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3180d0a8d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura H, Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Sudo T, Ohge H, et al. Predictive factors for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1321–1327. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0896-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaman L, Sanyal S, Behera A, Singh R, Katariya RN. Isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy vs. single loop pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Int J Surg. 2008;6:306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perwaiz A, Singhal D, Singh A, Chaudhary A. Is isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy superior to conventional reconstruction in pancreaticoduodenectomy? HPB. 2009;11:326–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutton CD, Garcea G, White SA, O'Leary E, Marshall LJ, Berry DP, et al. Isolated Roux-loop pancreaticojejunostomy: a series of 61 patients with zero postoperative pancreaticoenteric leaks. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:701–705. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ke S, Ding XM, Gao J, Zhao AM, Deng GY, Ma RL, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of Roux-en-Y reconstruction with isolated pancreatic drainage versus conventional loop reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 2013;153:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pratt WB, Maithel SK, Vanounou T. Clinical and economic validation of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification scheme. Ann Surg. 2007;245:443–451. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251708.70219.d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeOliveira ML, Winter JM, Schafer M, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, et al. Assessment of complications after pancreatic surgery: a novel grading system applied to 633 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2006;244:931–937. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000246856.03918.9a. discussion 937–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alberti KGMM, Hockaday TAR. Diabetes mellitus. In: Weatherall DJ, Ledingham JGG, Warrell DA, editors. Oxford Textbook of Medicine. 2nd edn. New York, NY: Oxford Medical Publications; 1987. pp. 9.51–9.101. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rault A, SaCunha A, Klopfenstein D, Larroudé D, Epoy FN, Collet D, et al. Pancreaticojejunal anastomosis is preferable to pancreaticogastrostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy for longterm outcomes of pancreatic exocrine function. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bassi C, Falconi M, Molinari E, Salvia R, Butturini G, Sartori N, et al. Reconstruction by pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy following pancreatectomy: results of a comparative study. Ann Surg. 2005;242:767–771. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000189124.47589.6d. discussion 771–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen Y, Jin W. Reconstruction by pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy following pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/627095. doi: 10.1155/2012/627095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernández-Cruz L, Cosa R, Blanco L, López-Boado MA, Astudillo E. Pancreatogastrostomy with gastric partition after pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy versus conventional pancreatojejunostomy: a prospective randomized study. Ann Surg. 2008;248:930–937. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818fefc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai EC, Lau SH, Lau WY. Measures to prevent pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy: a comprehensive review. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1074–1080. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casadei R, Zanini N, Pezzilli R, Calculli L, Ricci C, Antonacci N, et al. Reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy: isolated Roux loop pancreatic anastomosis. Chir Ital. 2008;60:641–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan AW, Agarwal AK, Davidson BR. Isolated Roux loop duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy avoids pancreatic leaks in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Dig Surg. 2002;19:199–204. doi: 10.1159/000064213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kingsnorth AN. Safety and function of isolated Roux loop pancreaticojejunostomy after Whipple's pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1994;76:175–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machado MC, Monteiro Cunha JE, Bacchella T, Bove P, Raia A. A modified technique for the reconstruction of the alimentary tract after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1976;143:271–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Funovics JM, Zoch G, Wenzl E, Schulz F. Progress in reconstruction after resection of the head of pancreas. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987;164:545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papadimitriou JD, Fotopoulos AC, Smyrniotis B, Prahalias AA, Kostopanagiotou G, Papadimitriou LJ. Subtotal pancreatoduodenectomy: use of a defunctionalized loop for pancreatic stump drainage. Arch Surg. 1999;134:135–139. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer C, Rohr S, De Manzini N, Thiry CL, Firtion O. Pancreatico-jejunal anastomosis with invagination on isolated loop after cephalic pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Ital Chir. 1997;68:613–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albertson DA. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with reconstruction by Roux en Y pancreaticojejunostomy: no operative mortality in a series of 25 cases. South Med J. 1994;87:197–201. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199402000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fragulidis GP, Arkadopoulos N, Vassiliou I, Marinis A, Theodosopoulos T, Stafyla V, et al. Pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: the impact of the isolated jejunal loop length and anastomotic technique of the pancreatic stump. Pancreas. 2009;38:e177–e182. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181b57705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ballas K, Symeonidis N, Rafailidis S, Pavlidis T, Marakis G, Mavroudis N, et al. Use of isolated Roux loop for pancreaticojejunostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3178–3182. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i25.3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wayne MG, Jorge IA, Cooperman AM. Alternative reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:9. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma YG, Li XS, Chen H, Wu MC. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with Roux-Y anastomosis in reconstructing the digestive tract: report of 26 patients. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2002;1:611–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe M, Usui S, Kajiwara H, Nakamura M, Sumiyama Y, Takada T, et al. Current pancreatogastrointestinal anastomotic methods: results of a Japanese survey of 3109 patients. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:25–33. doi: 10.1007/s00534-003-0863-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleespies A, Albertsmeier M, Obeidat F, Seeliger H, Jauch KW, Bruns CJ. The challenge of pancreatic anastomosis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:459–471. doi: 10.1007/s00423-008-0324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Maher MM. A prospective randomized trial of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1992;222:580–588. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199510000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duffas JP, Suc B, Msika S, Fourtanier G, Muscari F, Hay JM, et al. French Associations for Research in Surgery. A controlled randomized multicentre trial of pancreatogastrostomy or pancreatojejunostomy after pancreatoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 2005;189:720–729. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niedergethmann M, Dusch N, Widyaningsih R, Weiss C, Kienle P, Post S. Risk-adapted anastomosis for partial pancreaticoduodenectomy reduces the risk of pancreatic fistula: a pilot study. World J Surg. 2010;34:1579–1586. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0521-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wellner U, Makowiec F, Fischer E, Hopt UT, Keck T. Reduced postoperative pancreatic fistula rate after pancreatogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:745–751. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0763-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tran TCK, Kazemier G, Pek C, van Toorenenbergen AW, van Dekken H, van Eijck CHJ. Pancreatic fibrosis correlates with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after pancreatoduodenectomy. Dig Surg. 2008;25:311–318. doi: 10.1159/000158596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nodback I, Parviainen M, Piironen A, Räty S, Sand J. Obstructed pancreaticojejunostomy partly explains exocrine insufficiency after pancreatic head resection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:263–270. doi: 10.1080/00365520600849174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grobmyer SR, Hollenbeck ST, Jaques DP, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo R, Coit DG, et al. Roux-en-Y reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1184–1188. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pozzo G, Amerio G, Bona R, Castagna E, Parisi U, Sorisio V, et al. A new method of jejunal reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:1305–1308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]