Abstract

Purpose.

Ocular neovascularization (NV), the primary cause of blindness, typically is treated via inhibition of VEGF-A activity. However, besides VEGF-A, other proteins of the same family, including VEGF-B and placental growth factor (PlGF, all together VEGFs), have a crucial role in the angiogenesis process. PlGF and VEGF, which form heterodimers if co-expressed, both are required for pathologic angiogenesis. We generated a PlGF1 variant, named PlGF1-DE, which is unable to bind and activate VEGFR-1, but retains the ability to form heterodimer. PlGF1-DE acts as dominant negative of VEGF-A and PlGF1wt through heterodimerization mechanism. The purpose of our study was to explore the therapeutic potential of Plgf1-de gene in choroid and cornea NV context.

Methods.

In the model of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization (CNV), Plgf1-de gene, and as control Plgf1wt, LacZ, or gfp genes, were delivered using adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector by subretinal injection 14 days before the injury. After 7 days CNV volume was assessed. Corneal NV was induced by scrape or suture procedures. Expression vectors for PlGF1wt or PlGF1-DE, and as control the empty vector pCDNA3, were injected in the mouse cornea after the vascularization insults. NV was evaluated with CD31 and LYVE-1 immunostaining.

Results.

The expression of Plgf1-de induced significant inhibition of choroidal and corneal NV by reducing VEGF-A homodimer production. Conversely, the delivery of Plgf1wt, despite induced similar reduction of VEGF-A production, did not affect NV.

Conclusions.

Plgf1-de gene is a new therapeutic tool for the inhibition of VEGFs driven ocular NV.

The present study proposes the use of a PlGF variant, named PlGF1-DE, as a new tool for the inhibition of VEGF-dependent choroidal and corneal neovascularization by gene therapy. This variant is able to act as a dominant negative of pro-angiogenic VEGFs via heterodimerization mechanism.

Introduction

Ocular neovascularization (NV) is the primary cause of blindness in a wide range of common ocular diseases, including diabetic retinopathy (DR), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), and age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and various corneal diseases.1

In the normal mature ocular vascular system, angiogenic stimulating factors and angiogenic inhibitors exist in a homeostatic balance. In a variety of pathologic conditions, such as hypoxia, ischemia, inflammation, infection, and trauma, the balance between angiogenic stimulators and inhibitors is disrupted, leading to formation of pathologic vessels.2 Among these factors, the VEGF-A expression is increased markedly in the diabetic retina and vitreous, neovascular AMD lesions, and inflammation-associated corneal neovascularization.3–6

Consequently, the VEGF-A has been the main target for new therapeutic approaches aimed to block ocular NV. In particular, anti–VEGF-A antibodies or derived Fab fragments are the mainstay of treatment for CNV, which is the major cause of blindness in AMD.7–9 More recently, several prospective randomized studies have demonstrated that the intravitreal delivery of anti–VEGF-A antibodies also is effective for patients with DR.10 Although this treatment dramatically improves vision in most patients, it requires repeated intravitreous injections for an infinite period, and safety concerns regarding continual blockage of VEGF-A, which is expressed constitutively in the normal adult human retina, are emerging.11–13

For these reasons, a new way to target VEGF-A to avoid repeated intravitreous injection as well as the ability to target other pro-angiogenic factors in choroidal neovascularization (CNV) is desired.

Besides VEGF-A, other proteins of the same family have a pro-angiogenic activity, such as VEGF-B and placental growth factor (PlGF). These members of the VEGF family exert their activity through the binding and activation of two VEGF receptors, VEGFR-1 (also known as Flt-1) recognized by all three VEGF members, and VEGFR-2 (also known as Flk-1 in mice and KDR in humans) specifically recognized by VEGF-A.14

Furthermore, PlGF and VEGF-A share a strict biochemical and functional relationship because, besides having VEGFR-1 as a common receptor, they also can form heterodimer if co-expressed in the same cell.15 The heterodimer may induce receptor heterodimerization, like VEGF-A, or bind to VEGFR-1.16,17 Recently we showed that the ability of VEGF and PlGF to generate heterodimer may be used successfully to inhibit pathologic angiogenesis associated with tumor growth.17,18 In this perspective, we generated a PlGF1 variant, named PlGF1-DE,19 which is unable to bind and activate VEGFR-1, but retains the ability to form heterodimer with VEGF-A, with the idea that PlGF1-DE may act as a dominant negative of VEGF-A via heterodimerization. Indeed, the intratumor delivery of Plgf1-de by gene therapy forced the formation of PlGF1-DE/VEGF-A heterodimer, a complex unable to signal through VEGFR-1 homodimer and VEGFR-1/VEGFR-2 heterodimer. At the same time, a reduction of active PlGFwt homodimer, due to the generation of PlGF1-DE/PlGFwt dimer was observed.17 As a consequence, the concentration of active VEGF-A and PlGFwt homodimers was lowered resulting in a strong inhibition of pathologic neovascularization.

Therefore, the PlGF1-DE variant represents a novel inhibitor of VEGF-driven angiogenesis acting as a dominant negative when overexpressed in cells expressing pro-angiogenic VEGFs.

In our study we sought to explore further the therapeutic potential of Plgf1-de gene in the context of ocular pathologic neovascularization evaluating its activity in the experimental models of choroid and cornea NV, because in these ocular compartments VEGF-A is the main driving force for NV. Moreover, since VEGF-A has an important role also in corneal lymphangiogenesis, which is involved in different corneal pathologies as well as in transplant rejection,20 we also investigated the potential role of Plgf1-de as anti-lymphatic agent.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and Viral Vectors

The expression vector pCDNA3 carrying the full-length human cDNA for PlGF1wt (pPlGF1wt), or the variant PlGF1-D72→A-E73→A (pPlGF1-DE), were generated as described previously.19 Adeno-associated viruses (AAV) serotype 2 or serotype 5 expressing PlGF1-DE, PlGF1wt, and as control LacZ or GFP, were generated using AAV Helper−Free System (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA). The expression of cDNAs was under the control of cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. The physical titer of recombinant AAVs was determined by quantifying vector genome copies (vgc) packaged into viral particles, by real-time PCR against a standard curve of a plasmid containing the vector genome. Briefly, purified viral capsids were digested with proteinase K for 1 hour at 56°C. After enzyme inactivation at 95°C for 5 minutes, the digested mixture was diluted 10-fold and subjected to real-time PCR using TaqMan technology with primers and probe designed to recognize specifically sequences on the CMV promoter.

Cell Culture and AAV Infection

Human tumor cell lines A2780 (ECACC cat. n. 93112519, from ovarian carcinoma) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, and standard concentration of antibiotics. Then, 3 × 105 cells were plated in a 6-well multiplate. After 24 hours cells were exposed to AAV2-PlGF1-DE, AAV2-PlGF1wt, or AAV2-pCDNA3 with a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 5 × 104 for 48 hours. The culture medium was recovered, centrifuged to eliminate cell debris, and stored at −20°C for ELISA analysis.

ELISA Assays

The sandwich ELISA to quantify PlGF and VEGF-A dimers were performed as described previously17,19 with the following modifications. All the reagents used in ELISA were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). To avoid the interference of the heterodimer in the quantification of PlGF and VEGF-A homodimers, for PlGF determination samples were pre-incubated with anti–VEGF-A antibody coated on ELISA plate at 1 μg/mL, while for VEGF-A determination, samples were pre-incubated with anti-PlGF antibody, coated at 1 μg/ml. To quantify the PlGF/VEGF-A heterodimer in the culture medium of A2780 cells, antibody anti-PlGF was coated on ELISA plate, while biotinylated antibody anti–VEGF-A was used in solution. As reference, human recombinant VEGF-A, PlGF, and VEGF/PlGF dimers were used. PlGF, VEGF-A, and PlGF/VEGF-A concentrations were determined by interpolation with the relative standard curves, using linear regression analysis. For the evaluation of the presence of hPlGF1/mVEGF-A heterodimer in corneal extracts, anti-hPlGF antibody was used in capture while biotinylated antibody anti–mVEGF-A was used in solution. Due to the absence of recombinant inter-species heterodimer, standard curves were performed on the same ELISA plate contemporarily for mVEGF-A and hPlGF1 homodimers, and the concentrations reported were calculated by interpolation on the average of the two curves. For each determination, two independent experiments were performed, in which each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Animals

All animal experiments were in accordance with the guidelines of the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Animal Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. C57Bl6/J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). For all procedures, anesthesia was performed by intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride (Ft. Dodge Animal Health, Ft. Dodge, IA) and 10 mg/kg xylazine (Phoenix Scientific, St. Joseph, MO). Pupils were dilated with topical tropicamide (1%; Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX).

CNV Model

Subretinal injections (1 μL) in mice were performed using a Pico-Injector (PLI-100; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). AAV2-PlGF1-DE, AAV2-PlGF1wt, or AAV2-LacZ were injected at 4.0 × 1011 vgc/mL. AAV5-PlGF1-DE, AAV5-PlGF1wt, or AAV5-GFP were injected at 2.8 × 1011 vgc/ml. After 14 days CNV had been induced by laser photocoagulation (532 nm, 200 mW, 100 ms, 75 μm; OcuLight GL; IRIDEX Corporation, Mountain View, CA) performed on both eyes (4 spots per eye for volumetric analyses) of each 6- to 8-week-old male mice (N = 4 per group). As further control, 2 ng of antimouse VEGFA polyclonal antibody (R&D Systems) in 1 μL of PBS were delivered intravitreous just after the laser injury (N = 4 per group). Seven days later CNV volumes were measured by staining with 0.5% FITC-conjugated Griffonia simplicifolia Isolectin B4 (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) RPE-choroidal flat mounts using scanning laser confocal microscope (TCS SP; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), as reported previously.21,22 CNV volumes per laser lesion were compared by hierarchical logistic regression using repeated measures analysis.

Electroretinography (ERG) and Histology

In anesthetized 6- to 8-week-old male mice (N = 4 per group) 1 μL of AAV5-GFP, AAV5-PlGF1wt, or AAV5-PlGF1-DE preparations, and as control PBS, were delivered intravitreous on days zero and three. On day seven, mice were dark adapted overnight, anesthetized, and both eyes were positioned within a ColorBurst Ganzfeld stimulator (E2; Diagnosys, Lowell, MA). After placing corneal and ground electrodes, Espion software (Diagnosys) was used to deliver a fully automated flash intensity series from which retinal responses were recorded.

Thereafter, eyes were enucleated and flash-frozen in isopentane cooled with liquid nitrogen. Sections (7–8 μm) were cut, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Morphologic analysis was performed by measurement of retinal inner and outer nuclear layers (INL and ONL, respectively) thickness on three randomly selected areas for each eye, using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD).

Cornea Scrape Procedure and Protein Extraction

We applied 2 μL of 0.15M NaOH to the surface of the corneas of both eyes of 6- to 8-week-old male mice (N = 4 per group) for 1 minute and washed with PBS. The corneal epithelium was removed on both eyes with a corneal scraper, and 8 ng of each plasmid, pPlGF1wt, pPlGF1-DE, or pCDNA3, in 4 μL of PBS were injected into the corneal stroma with a 33-gauge Exmire microsyringe (Ito Corporation, Fuji, Japan). The animals were euthanized 48 hours later, the eyes were enucleated, and the corneas were dissected for proteins extraction. As control, scraped and untouched corneas were dissected. Corneas were minced with scissors, and sonicated in RIPA buffer. After centrifugation at 14,800 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 15 minutes at 4C°, the supernatants were recovered and protein concentration determined by Bradford method (Bio-Rad assay; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Cornea Suture Procedure

In anesthetized animals, two interrupted 11-0 nylon sutures (Mani, Inc., Utsunomiya, Japan) were placed into the corneal stroma, midway between the central corneal apex and the limbus (approximately 1.25 mm from the limbus), of both eyes of 6- to 8-week-old male mice (N = 12 per group). Delivery of 5 ng of plasmids pPlGF1wt or pPlGF1-DE versus empty vector pcDNA3 in 5 μL of PBS was done into corneal stroma at day zero (suture placement) following injection every three days for 14 days. Injections were performed using a 33-gauge Exmire Microsyringe (Ito Corporation). Animals were sacrificed at day 14, the eyes were enucleated, and the corneas were dissected for further analyses.

Corneal Flat Mounts

After euthanasia, the corneas were isolated, washed in PBS, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour and acetone for 20 minutes at room temperature. Corneas were washed in 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS and blocked in 3% BSA in PBS for 48 hours. Incubation with rabbit anti-mouse LYVE-1 antibody (1:333; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and rat anti-mouse CD31 antibody (1:50; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was performed for 48 hours at 4°C. The corneas were washed in 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS and incubated for 2 hours with Alexa Fluor 488 (goat anti-rabbit; 1:200; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Alexa Flour 594 (goat anti-rat; 1:200; Invitrogen). Corneal flat mounts were visualized under fluorescent microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The images were adjusted for brightness/contrast, and converted to black and white images. Next, whole corneas were outlined using ImageJ software (NIH). Contours of lymphatic or bloodstained vessels inside the previously outlined area were optimized by threshold and converted to binary images. Area fraction (%) of neovascularized cornea was calculated compared to whole corneal surface.

Statistic Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Differences among groups were tested by one-way ANOVA. Tukey HD test was used as a post hoc test to identify which group differences account for the significant overall ANOVA.

All calculations were carried out using SPSS statistical package (vers12.1; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

AAV-PlGF1s Transduction of VEGF-A–Producing Cells Induced Reduction of VEGF-A Homodimer by Heterodimer Formation

To evaluate the activity of PlGF1-DE in the model of choroid-NV, we planned to deliver the Plgf1-de and Plgf1wt genes using AAV as vector. To check if the transduction of AAVs carrying Plgf genes effectively causes a decrease of VEGF-A production by PlGF1/VEGF-A heterodimer formation, AAV2-PlGF1wt and AAV2-PlGF1-DE viral particles were used to infect a VEGF-A–producing/PlGF-nonproducing human tumor cell line derived from ovarian carcinoma (A2780). As reported in the Table, the transduction of both forms of PlGF determined a similar decrease of VEGF-A homodimer production (0.61 and 0.71 ng/mL for AAV2-PlGF1wt and AAV2-PlGF1-DE compared to AAV-pCDNA3) to which corresponded the appearance of PlGF1/VEGF-A heterodimer. As expected, the concentration of the heterodimer (1.43 and 1.32 ng/mL for AAV2-PlGF1wt and AAV2-PlGF1-DE, respectively) resulted in close to twice the reduction of VEGF-A, since for each molecule of VEGF-A homodimer subtracted, two molecules of heterodimer may be formed.

Table. .

Quantification of PlGF and VEGF-A Dimers in the Culture Medium of A2780 Cells Transduced with AAV2 Viral Vectors, and in the Corneal Protein Extracts following Scrape Procedure and Injection in the Corneal Stroma of Nude Plasmids

|

A2780 Culture Medium |

hVEGF-A |

hVEGF-A/hPlGF |

hPlGF |

| PBS | 2.32 ± 0.31 | ND | ND |

| AAV2-pCDNA3 | 2.12 ± 0.24 | ND | ND |

| AAV2-pPlGF1wt | 1.51 ± 0.13* | 1.43 ± 0.32 | 30.12 ± 3.32 |

|

AAV2-pPlGF1-DE |

1.41 ± 0.12* |

1.32 ± 0.22 |

32.42 ± 3.11 |

|

Corneal Extracts |

mVEGF-A |

mVEGF-A/hPlGF |

hPlGF |

| Normal cornea | 0.58 ± 0.04 | ND | ND |

| Scrape | 1.80 ± 0.11 | ND | ND |

| pCDNA3 | 1.72 ± 0.10 | ND | ND |

| pPlGF1wt | 0.92 ± 0.17† | 1.45 ± 0.12 | 0.95 ± 0.09 |

| pPlGF1-DE | 0.98 ± 0.16† | 1.37 ± 0.08 | 0.90 ± 0.04 |

The values, expressed as ng/mL for A2780 culture medium and ng/mg of protein for corneal extracts, represent the average ± SEM of two independent experiments, in which each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

P < 0.05 versus AAV2-pCDNA3 and PBS.

P < 0.003 versus pCDNA3 and scrape groups.

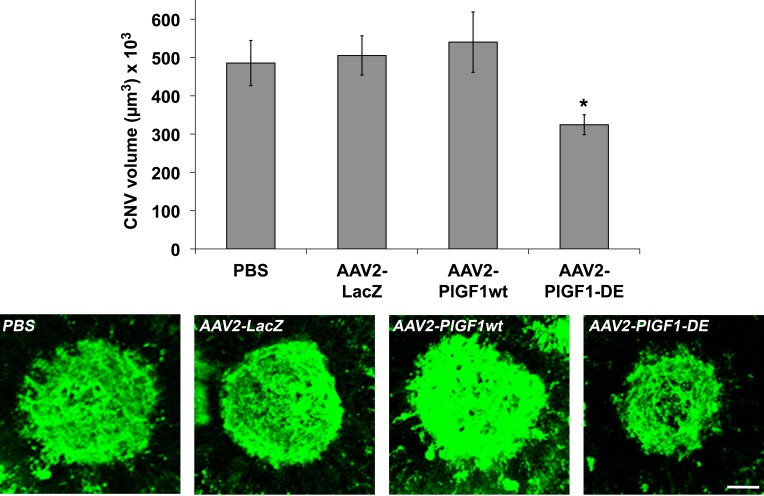

AAV-PlGF1-DE Inhibits Laser-Induced Choroid Neovascularization

We first evaluated the activity of PlGF1-DE in the laser-induced choroid NV. RPE cells represent the first target because they express a high level of VEGF-A in pathologic conditions.5 For this reason, in the first experiment, the delivery of therapeutic genes was achieved using AAV vector of serotype 2, by subretinal injection of AAV2-PlGF1-DE, AAV2-PlGF1wt, and AAV2-LacZ (4.0 × 1011 vgc/mL), or PBS, as control. As shown in Figure 1, AAV2-PlGF1-DE was able to inhibit choroid-NV compared to AAV2-LacZ (−35.7%, P = 0.0037), to AAV2-PlGF1wt (−39.9%, P = 0.0144), and to the PBS group (−33.2%, P = 0.0183). Therefore, only PlGF1-DE was able to inhibit choroid-NV while the transduction of PlGF1wt did not interfere in new blood vessel formation and did not induce an increase of neovascularization, compared to the control.

Figure 1. .

AAV2-PlGF1-DE inhibits CNV but AAV2-PlGF1wt does not. CNV volumes were measured by confocal evaluation of Isolectin B4 staining of RPE-choroid flat mounts (4 animals per group). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. *P = 0.0037 versus AAV2-LacZ; P = 0.0144 versus AAV2-PlGF1wt. Representative pictures of CNV flat mounts. Scale bar: 100 μm.

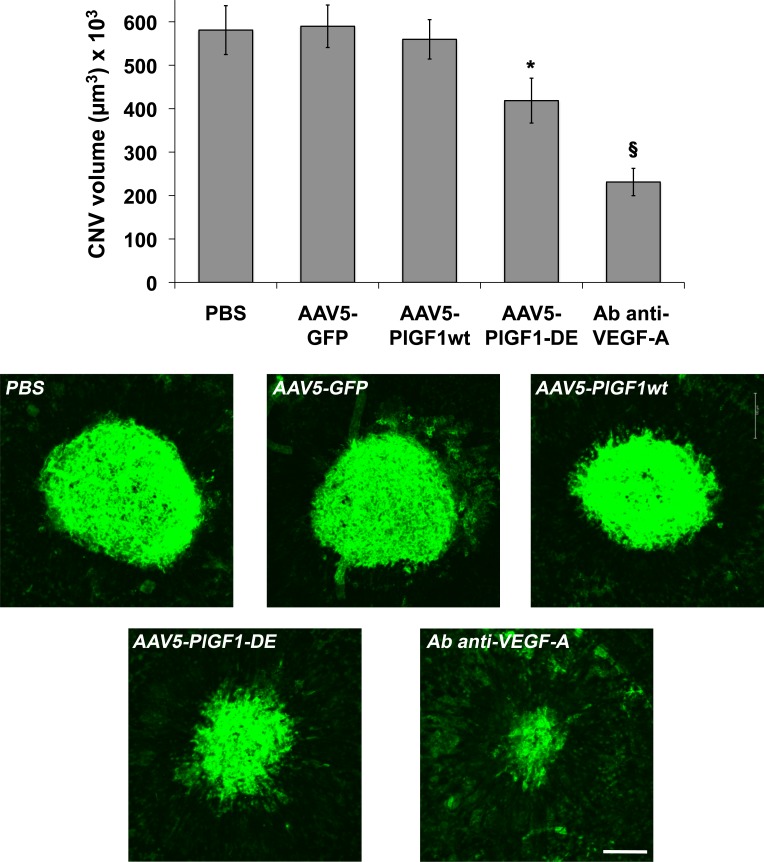

Since it has been reported that AAV serotype 5 infects not only RPE cells, but also photoreceptor (PR) cells,23 which also express VEGF-A in pathologic context,24 new AAV5 vectors for PlGF1-DE, PlGF1wt, and GFP as control, were generated and injected subretinally (2.8 × 1011 vgc/mL).

We did not observe important differences between the two serotypes. Once again only the transduction of PlGF1-DE inhibited choroid-NV with an extent close to that observed with serotype 2 (−29.1%, P = 0.0257 versus AAV5-GFP; −25.2%, P = 0.0491 versus AAV5-PlGF1wt; −27.9%, P = 0.0455 versus PBS) while the transduction of PlGF1wt did not change the extent of neovascularization (Fig. 2). As positive control of inhibition, the intravitreal injection of antibodies anti-mVEGF induced a strong inhibition of choroid-NV (−60%, P < 0.0001 versus PBS). The slightly lower inhibition observed using AAV5 might be almost in part due to the different amounts of AAV vgc injected, which have represented the maximum amount for each serotype that we have been able to inject to obtain a correct comparison with relative controls.

Figure 2. .

AAV5-PlGF1-DE inhibits CNV but AAV5-PlGF1wt does not. CNV volumes were measured by confocal evaluation of Isolectin B4 staining of RPE-choroid flat mounts (4 animals per group). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. *P = 0.0257 versus AAV5-GFP, P = 0.0491 versus AAV5-PlGF1wt, P = 0.0455 versus PBS. §P < 0.0001 for antibody anti–VEGF-A versus PBS. Representative pictures of choroid-NV. Scale bar: 100 μm.

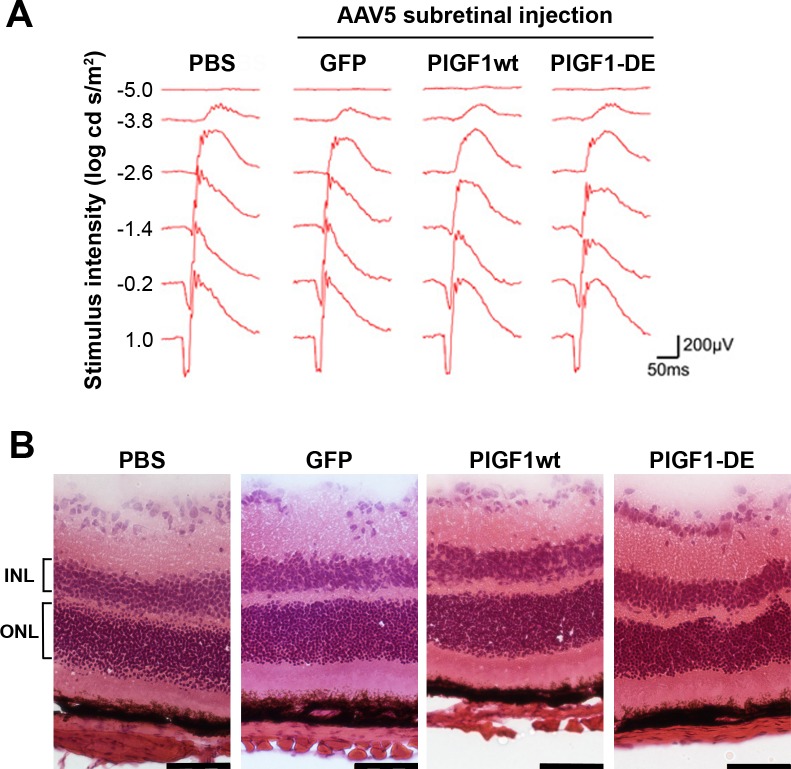

The injections of AAV vectors did not induce toxicity as evidenced by ERG (Fig. 3A), as well as by morphologic analysis performed on H&E-stained retinal sections (Fig. 3B). Indeed, ONL thickness (μm ± SEM, PBS 52.5 ± 2.3, AAV5-GFP 53.4 ± 1.6, AAV5-PlGF1wt 52.8 ± 2.6, AAV5-PlGF1-DE 49.4 ± 4.8) as well as INL thickness (PBS 31.3 ± 4.1, AAV5-GFP 30.6 ± 3.5, AAV5-PlGF1wt 29.3 ± 3.7, AAV5-PlGF1-DE 30.2 ± 3.2) did not show significant differences between the groups analyzed.

Figure 3. .

ERG and histochemical analyses of retinas after AAV5 delivery. Intravitreous administration (4 animals per group) of AAV5-GFP, AAV5-PlGF1wt, or AAV5-PlGF1-DE did not induce retinal damage as monitored by ERG and histochemical analysis, compared to PBS. (A) Representative wave form and amplitude responses during scopic flash ERG. (B) Representative pictures of H&E-stained sections illustrating the normal retina morphology. ONL thickness (expressed in μm ± SEM), PBS 52.5 ± 2.3, AAV5-GFP 53.4 ± 1.6, AAV5-PlGF1wt 52.8 ± 2.6, AAV5-PlGF1-DE 49.4 ± 4.8. INL thickness (expressed in μm ± SEM), PBS 31.3 ± 4.1, AAV5-GFP 30.6 ± 3.5, AAV5-PlGF1wt 29.3 ± 3.7, AAV5-PlGF1-DE 30.2 ± 3.2. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Expression of hPlGFs Induced hPlGF1/mVEGF-A Heterodimer Formation in the Cornea

Scrape procedure was performed to induce VEGF-A overexpression in corneas. To evaluate if the injection in the corneas of nude expression vectors carrying the cDNA for human PlGF1-DE or PlGF1wt was sufficient to induce the generation of hPlGF1/mVEGF-A heterodimers, with consequent reduction of mVEGF-A homodimer production, plasmids were injected just after the scrape procedure and corneas were harvested 48 hours later for protein extraction. As control, corneas injected with empty vector, scraped corneas, and untouched corneas were used. The quantification of VEGF-A and PlGF1 dimers performed by sandwich ELISAs and reported in the Table, showed that the scrape procedure induced an increase of mVEGF-A concentration of approximately three-times, compared to untouched cornea. Similar concentration of mVEGF-A was observed in corneas injected with empty vector. Conversely, the extracts derived from corneas injected with pPlGF1-DE or pPlGF1wt showed a reduction close to 50% of mVEGF-A, compared to scraped or empty vector-injected corneas, to which corresponded the presence of hPlGF1/mVEGF-A heterodimer. As expected, hPlGF1 homodimers were detected in corneal extracts.

These quantifications indicated that once injected expression plasmids for PlGF1-DE or PlGF1wt in scraped corneas, approximately 50% of mVEGF-A was engaged to form heterodimer with hPlGF1.

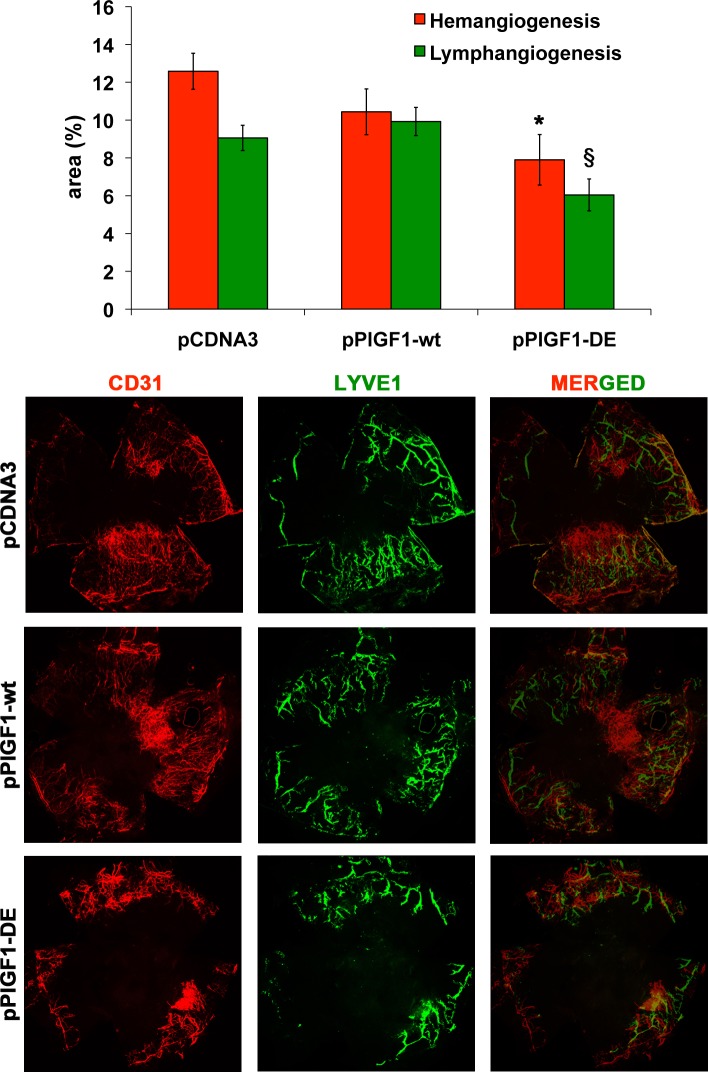

Expression of PlGF1-DE Inhibits Pathologic Cornea NV

To evaluate the effects of PlGF1-DE expression on pathologic cornea NV the suture-induced model was used. The plasmids pPlGF1wt, pPlGF1-DE, or pcDNA3 were injected immediately after the suture procedure and every three days for 14 days. The effect of plasmids expression was evaluated calculating the area of the new blood and lymphatic vessels. Since CD31 is a panendothelial marker that also recognizes lymphatic vessels, the quantification of hemangiogenesis was done subtracting from CD31 area the corresponding LYVE-1 area.

As shown in Figure 4, also in this pathologic model, only the expression of PlGF1-DE significantly inhibited suture-induced corneal NV compared to pCDNA3 (area % ± SEM, 7.90 ± 1.33 vs. 12.58 ± 0.95, −37.2%, P = 0.0072), while the expression of PlGF1wt did not change in a significant manner the extent of neovascularization compared to empty vector (10.44 ± 1.21 vs. 12.58 ± 0.95). Interestingly, the expression of PlGF1-DE also induced a significant inhibition of lymphangiogenesis compared to pPlGF1wt and pcDNA3 transfected cornea (area % ± SEM, 6.04 ± 0.84 vs. 9.92 ± 0.74 and 9.06 ± 0.66, respectively, −39.1% and −33.3%, P < 0.01).

Figure 4. .

PlGF1-DE inhibits cornea NV but PlGF1wt does not. Cornea NV was measured by confocal evaluation of CD31 or LYVE-1 staining of cornea flat mounts (12 animals per group). Data are represented as the mean ± SEM. *P = 0.072 versus pCDNA3. §P < 0.01 versus pPlGF1wt and pcDNA3. Representative pictures of cornea stained with CD31 or LYVE-1 and merged images.

Discussion

Currently, the inhibition of VEGF-A achieved by delivery of Avastin or Lucentis has become the main therapeutic strategy for the inhibition of ocular NV diseases.10,25 Although the results are encouraging, two main problems must be resolved. First, the use of these drugs requires continuous intravitreous injections. Second, the continuous blockage of VEGF-A, which is expressed physiologically in the normal adult human retina, determines safety concerns.11–13 Consequently, new strategies to avoid repeated intravitreous injection, to target VEGF-A avoiding full block of its activity, and to block also other pro-angiogenic factors of the family are desired.

In this perspective, we decided to evaluate if the property of VEGF-A and PlGF to form heterodimer when co-expressed could represent a successful strategy to reduce VEGF-A–dependent choroid and corneal NV. This is what we demonstrated previously in tumor context that the variant PlGF1-DE, in which the two residues D72 and E73 essential for Flt-1 recognition and binding were changed to alanine,19 acts as dominant negative of VEGF-A and PlGFwt via heterodimerization mechanism.17,18 As results, a decrease of production of active VEGF-A and PlGFwt homodimers was achieved. Therefore, we decided to deliver the human Plgf1-de gene using AAV vectors in a laser-induced CNV model, or using nude DNA in scrape- and suture-induced cornea NV models.

First, we verified that the delivery of therapeutic gene using AAV as vector or nude expression plasmid was sufficient to induce heterodimer generation. Data reported in the Table confirmed that transduction of a VEGF-A producing/PlGF non-producing cell line (A2780) with AAV2 vector carrying human Plgf1-de or Plgf1wt genes, determined the appearance of PlGF1/VEGF-A heterodimer and a significant similar reduction (approximately 35%) of VEGF-A homodimer in the culture medium. In the same manner, the injection of nude expression vector for PlGF1-DE or PlGF1wt in the stroma of scraped corneas determined a significant similar reduction (approximately 50%) of mVEGF-A homodimer production, and the appearance of hPlGF1/mVEGF-A heterodimer. In both experimental contexts, the quantity of heterodimer measured was close to twice the reduction of VEGF-A homodimer, as expected since for each molecule of homodimer VEGF-A depleted, two molecules of heterodimer may be formed.

Only the expression of Plgf1-de gene determined significant inhibition of NV in choroid and corneal models, compared to the expression of Plgf1wt gene or other controls. In the CNV model, the use of AAV2 or AAV5 serotypes, both able to infect RPE cells, the second also PR cells, gave similar inhibition extents indicating that VEGF-A seems to be expressed mainly by RPE cells in this pathologic context.

It is interesting to highlight that the overexpression of Plgf1wt gene did not determine changes in CNV, compared to AAV2-LacZ or AAV5-GFP, as well as in cornea NV, compared to empty vector pCDNA3, despite that its expression induced a reduction of active VEGF-A homodimer similar to that observed overexpressing Plgf1-de gene (see Table). The difference between the overexpression of Plgf1-de gene or Plgf1wt gene was that in the first case two inactive dimers, PlGF1-DE homodimer and PlGF1-DE/VEGF-A heterodimer, were produced, whereas in the second case active PlGF1wt homodimer and PlGF1wt/VEGF-A heterodimer were produced, which have been able to rescue the effect due to reduction of VEGF-A homodimer. This highlights the possible active role that these other members of the VEGF family may have in the process of pathologic ocular NV.

Remarkably, in the corneal suture–induced NV model, we also observed a significant decrease of lymphangiogenesis exclusively after overexpression of Plgf1-de gene. This result is in agreement with many recent data indicating that VEGF-A homodimer has an active role also in the stimulation of neolymphatic vessels formation20 and that its block also inhibits lymphangiogenesis.26,27

The delivery of Plgf1-de gene, in particular those with AAV vector, fulfills all the three requirements remarked previously in the perspective of more affordable anti–VEGF-A therapy. The gene therapy approach avoids the repeated intravitreous injections needed for therapeutic antibodies, while the heterodimerization mechanism does not block VEGF-A fully and also may act on other VEGF family members, mainly on PlGF.

In conclusion, the Plgf1-de gene represents a new interesting tool for anti-angiogenic therapy in the context of ocular NV pathologic conditions. The possibility to increase its expression in a more potent and cell specific manner to induce further decrease of VEGF-A production represents the next step to evaluate better its applicability for therapeutic purpose.

Acknowledgments

Robinette King, Charles Payne, Darrell Robertson, Gary R. Pattison, and Vincenzo Mercadante provided technical assistance, and Anna Maria Aliperti provided manuscript editing.

Footnotes

Supported by AIRC (Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro, Grant IG 11420; SDF), Telethon – Italy (Grant GGP08062, SDF), and Italian Ministry of Scientific Research (Grant MERIT in oncology, SDF); and by NEI/NIH Grants R01EY018350, R01EY018836, R01EY020672, R01EY022238, R21EY019778, and RC1EY020442 (JA), Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Scientist Award (JA), Burroughs Wellcome Fund Clinical Scientist Award in Translational Research (JA), Dr. E. Vernon Smith and Eloise C. Smith Macular Degeneration Endowed Chair (JA), and Senior Scientist Investigator Award (Research to Prevent Blindness, RPB; JA).

Disclosure: V. Tarallo, None; S. Bogdanovich, None; Y. Hirano, None; L. Tudisco, None; L. Zentilin, None; M. Giacca, None; J. Ambati, None; S. De Falco, None

References

- 1.Campochiaro PA, Hackett SF. Ocular neovascularization: a valuable model system. Oncogene. 2003;22:6537–6548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adamis AP, Miller JW, Bernal MT, et al. Increased vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the vitreous of eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118:445–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiello LP, Avery RL, Arrigg PG, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1480–1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez PF, Sippy BD, Lambert HM, Thach AB, Hinton DR. Transdifferentiated retinal pigment epithelial cells are immunoreactive for vascular endothelial growth factor in surgically excised age-related macular degeneration-related choroidal neovascular membranes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:855–868 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cursiefen C, Rummelt C, Kuchle M. Immunohistochemical localization of vascular endothelial growth factor, transforming growth factor alpha, and transforming growth factor beta1 in human corneas with neovascularization. Cornea. 2000;19:526–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gragoudas ES, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET Jr, Feinsod M, Guyer DR. Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2805–2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1432–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimoto K, Kubota T. Anti-VEGF agents for ocular angiogenesis and vascular permeability. J Ophthalmol. 2012;2012:852183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marneros AG, Fan J, Yokoyama Y, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in the retinal pigment epithelium is essential for choriocapillaris development and visual function. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1451–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saint-Geniez M, Maharaj AS, Walshe TE, et al. Endogenous VEGF is required for visual function: evidence for a survival role on Müller cells and photoreceptors. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saint-Geniez M, Kurihara T, Sekiyama E, Maldonado AE, D'Amore PA. An essential role for RPE-derived soluble VEGF in the maintenance of the choriocapillaris. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18751–18756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Falco S, Gigante B, Persico MG. Structure and function of placental growth factor. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002;12:241–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Falco S. The discovery of placenta growth factor and its biological activity. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiSalvo J, Bayne ML, Conn G, et al. Purification and characterization of a naturally occurring vascular endothelial growth factor · placenta growth factor heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7717–7723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarallo V, Vesci L, Capasso O, et al. A placental growth factor variant unable to recognize vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor-1 inhibits VEGF-dependent tumor angiogenesis via heterodimerization. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1804–1813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarallo V, Tudisco L, De Falco S. A placenta growth factor 2 variant acts as dominant negative of vascular endothelial growth factor A by heterodimerization mechanism. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:265–274 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Errico M, Riccioni T, Iyer S, et al. Identification of placenta growth factor determinants for binding and activation of Flt-1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43929–43939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakao S, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Ishibashi T. Lymphatics and lymphangiogenesis in the eye. J Ophthalmol. 2012;2012:783163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nozaki M, Raisler BJ, Sakurai E, et al. Drusen complement components C3a and C5a promote choroidal neovascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2328–2333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nozaki M, Sakurai E, Raisler BJ, et al. Loss of SPARC-mediated VEGFR-1 suppression after injury reveals a novel antiangiogenic activity of VEGF-A. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:422–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colella P, Cotugno G, Auricchio A. Ocular gene therapy: current progress and future prospects. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sayanagi K, Sharma S, Kaiser PK. Photoreceptor status after antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy in exudative age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:622–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin DF, Maguire MG, Ying GS, Grunwald JE, Fine SL, Jaffe GJ. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1897–1908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellenberg D, Azar DT, Hallak JA, et al. Novel aspects of corneal angiogenic and lymphangiogenic privilege. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010;29:208–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dellinger MT, Brekken RA. Phosphorylation of Akt and ERK1/2 is required for VEGF-A/VEGFR2-induced proliferation and migration of lymphatic endothelium. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]