Abstract

Objective

The objectives of this study were (1) to characterize the microbiome of the temporal artery in patients with giant cell arteritis and (2) to apply an unbiased and comprehensive shotgun sequencing-based approach to determine if there is an enrichment of candidate pathogens in affected tissues.

Methods

We performed unbiased DNA sequencing of 17 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded temporal artery biopsy specimens collected at a single institution over a period of four years. Twelve cases fulfilled clinical and histopathological criteria for GCA. Five cases served as controls. Using PathSeq software, human sequences were computationally subtracted and the remaining non-human sequences taxonomically classified using a comprehensive microbial sequence database. The relative abundance of microbes was inferred based on read counts assigned to each organism. Comparison of the microbial diversity in cases versus controls was carried out using hierarchical clustering and linear discriminant analysis effect size.

Results

Propionibacterium acnes and Escherichia coli were the most abundant microorganisms in 16 of the 17 samples and Moraxella catarrhalis was the most abundant organism in one control. Pathogens previously described to be correlated with GCA were not differentially abundant in cases, compared to controls. There was not a significant burden of likely pathogenic viruses.

Conclusion

DNA sequencing of temporal artery biopsies from GCA cases and controls showed no evidence of previously identified candidate GCA pathogens. A single pathogen was not clearly and consistently associated with GCA in this case series.

Introduction

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a granulomatous systemic vasculitis of the elderly, of unknown etiology. It is postulated to be an antigen driven disease whereby dendritic cells in the adventitia become activated by an unknown stimulus (1). Dendritic cells express Toll-like receptors, components of the innate immune system that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns. The ability of dendritic cells to recognize lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of Gram-negative bacteria, and components of other pathogens suggests that infectious agents may trigger this disease. Additionally, the report of an apparent spike in the incidence of GCA every five to seven years has implied the possibility of exposure to an infectious agent (2).

Previous studies have investigated the posited causal association between microbial infections and GCA using directed methods. Application of these targeted methods, such as polymerase chain reaction, has resulted in the detection of parvovirus B19, Chlamydia species, and varicella zoster virus in GCA, with conflicting results (3–5). Bradyrhizobium and Rhodopseudomonas sequences have been identified as differentially present in histopathologically inflamed regions of GCA temporal artery lesions compared to adjacent uninvolved tissues, using the nucleic acid-based method of representation difference analysis (6). Recently, a preliminary study using 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing proposed the presence of a Burkholderia-like strain in the temporal arteries of patients with GCA. (7), All reports identifying candidate pathogens in GCA have involved either targeted methodologies or extremely small cohorts, and have not yet been reproduced.

Next generation sequencing allows for comprehensive characterization of DNA or RNA sequences within a tissue sample, including both human and tissue-associated microbial species. We and others have demonstrated that the combination of sequencing of human specimens and subsequent characterization of the organisms from which these DNA or RNA sequences arise can be a powerful tool for the unbiased discovery of candidate pathogens and description of the tissue microbiome. These efforts have led to the discovery of an association between the Gram-negative Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer, as well as the de novo discovery of a novel hematopoietic stem cell transplantation colitis-associated organism, Bradyrhizobium enterica (8, 9). Despite the obvious power of these types of technologies, such efforts must be well-controlled and executed, as the introduction of contaminants has been described and can suggest microbe-disease associations that may be spurious (10).

Given the epidemiological and pathophysiological factors that support the possibility of the GCA-pathogen association, we aimed to employ an unbiased, sequencing-based approach to characterize the microbiome of temporal arteries from patients with GCA and non-GCA controls. Furthermore, we also sought to apply a sensitive and unbiased method to determine if a specific microbial pathogen or pathogens, either novel or as previously described, could be identified in the temporal arteries of patients with GCA.

Materials and Methods

Sample Selection

Seventeen temporal artery (TA) biopsy specimens were obtained from patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of GCA, at a single institution (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts). All TA biopsies were performed by the same neuro-ophthalmologist and were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded in the same pathology facility over a period of four years (from 2009–2012). Patient ages at the time of TA biopsy ranged from 66 to 88 (cases) and 69 to 86 (controls) (Table 1). Twelve cases had abnormal temporal artery biopsies with active inflammation diagnostic of GCA and fulfilled the 1990 ACR classification criteria for GCA. Five cases with histologically negative TA biopsies, for which the patients’ subsequent clinical courses showed no evidence for GCA, served as controls. Thirteen of the seventeen patients (four controls, nine cases) received steroids prior to biopsy, and two of the seventeen patients received antibiotics prior to biopsy; detailed medication information was not available for one control patient.

Table 1.

Summary of patient demographics and their treatment history prior to temporal artery biopsy.

| Description | Cases | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | Median age in years (Range) | 74 (66–88) | 70 (66–86) |

| Sex | % Male (n) | 17% (2) | 20% (1) |

| Prior therapy | |||

| % No Steroids (n) | 25% (3) | 20% (1) | |

| % Steroids (n) | 75% (9) | 80% (4) | |

| % Antibiotics (n) | 17% (2) | 0% (0) | |

| % Immunosuppression (n) | 8% (1) | 20% (1)*, ** | |

Patient 183 received Methotrexate for two months.

Patient 194 received Dexamethasone and Lenalidomide for multiple myeloma.

DNA extraction and Sequencing

Seventeen formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) temporal artery biopsy blocks were faced (shaved until the block was even) using new blades on a microtome. A 100um scroll of each block was collected. Genomic DNA was extracted using a RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit (Ambion), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bar-coded libraries were generated and 101-base pair, paired-end sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq V3 platform to a depth of approximately 3× whole genome sequence coverage, as previously described (8).

PathSeq Analysis

Sequences obtained were analyzed by PathSeq, a software algorithm that taxonomically classifies each sequencing read; this method and its tested limits of sensitivity have been previously described (8). Briefly, we used the PathSeq software (www.broadinstitute.org/software/pathseq), to (a) quality filter all reads, (b) computationally subtract human reads and (c) classify the remaining non-human reads using a comprehensive microbial reference sequence database (11).

Following taxonomic classification of the nonhuman reads, the relative abundance (RA) for each organism was calculated as follows: RA = (# unique alignment positions in genome × 1,000,000) / (# total alignable reads × genome size). The RA values were then normalized per sample in order to facilitate comparison of the microbiome between samples. Data were carefully reviewed for the presence of known bacterial and viral pathogens and for organisms previously described to be associated with GCA.

Comparative marker analysis was performed using the GENE-E software package to identify statistically significant differences between cases and controls (http://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/software/GENE-E/). Hierarchical clustering was also performed based on the composition of the microbiome in cases and controls (12). A linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) was performed to define class-based differences in the microbiome between cases and controls (13). Given the assumption that a candidate pathogen must be present at a moderate abundance, a median RA cutoff of 0.05% was applied for all bacteria and only organisms with a median RA values above this cutoff or LEfSe outputs with an effect size of greater than four LDA units were nominated as candidate pathogens.

Results

Patient characteristics

To determine if candidate pathogens in GCA could be identified using a comprehensive and unbiased sequencing-based approach, we analyzed the whole genome sequences of temporal artery biopsies of GCA patients and of controls. Age and gender distribution between cases and controls were comparable (Table 1). Males comprised 17% (n=2) of cases and 20% (n=1) of controls. A detailed clinical chart review was performed and revealed similar steroid and antibiotic exposure in each cohort. One control patient received immunosuppressive agents other than steroids (methotrexate); another control patient received the chemotherapeutic agent lenalidomide for treatment of multiple myeloma.

Sequencing results and PathSeq analysis

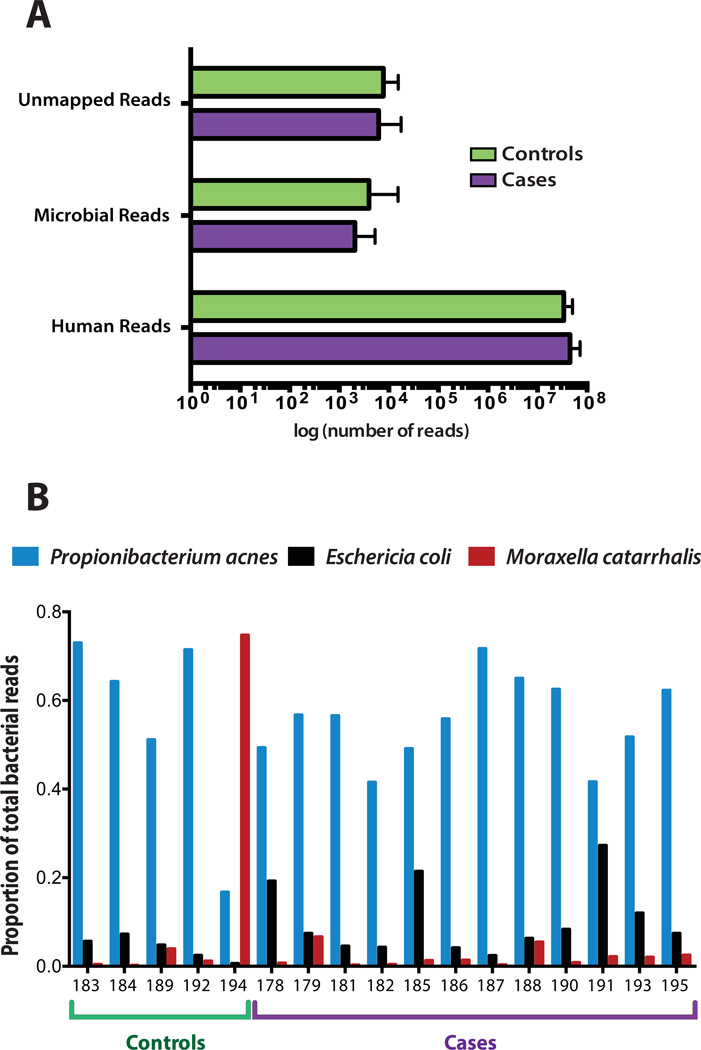

PathSeq was used to classify each sequence based on the organism of origin. We obtained a median of 43 million human reads (range: 30–72.2 million), 2,433 microbial reads (range: 907–5,254), and 6,337 unmapped reads (range: 3,490 – 17,706) per sample. Microbial reads included those corresponding to known bacteria, archaea, fungi and viruses. Reads corresponding to bacteriophage were excluded from this analysis as control libraries generated from the PhiX bacteriophage are often introduced during sequencing to enhance overall sequencing quality. The number of human reads, microbial reads, and unmapped reads were comparable between cases and controls (Figure 1a; Supplementary table 1). As the majority of sequences aligned to the human genome, the FFPE-extracted DNA can be inferred to be of high quality. Raw results (number of reads mapping to each microbial organism) of the taxonomic classification are presented in Supplementary table 2.

Figure 1. Whole genome sequence analysis of temporal artery biopsies from giant cell arteritis and control cases.

(A) Whole genome sequencing reveals a similar number of human, microbial (bacteria, viruses, archaea, and fungi), and unmapped reads between cases and controls. The median number of reads and their distribution is depicted. (B) Species level comparison of the three most abundant organisms. P. acnes was the most abundant organism in sixteen cases and E. coli was typically the second most abundant. M. catarrhalis was identified in high abundance in one control.

Microbial analysis

We compared the microbial composition of the temporal artery between GCA cases and controls to determine if biologically relevant differences could be identified. Other than rare HPV reads in one case (sample 185) (Supplementary table 2), no pathogenic viruses were identified, including previously reported GCA-associated organisms such as parvovirus B19 or varicella zoster virus (4, 14). No novel organisms emerged from an analysis of the unmapped reads.

The relative abundance (RA) of bacteria (Supplementary table 3) was calculated and was then corrected for the total number of human reads per sample (Supplementary table 4) for the 49 bacterial organisms with the highest mean abundance in cases and controls. The most abundant organism in 16 of the 17 patients studied was Propionibacterium acnes, a Gram-positive component of the skin flora. Escherichia coli, a facultative Gram-negative bacterium, and a component of the stool microbiome, was the second most abundant microorganism in most cases and controls. The only other highly abundant organism of note was Moraxella catarrhalis, a Gram-negative bacterium associated with upper respiratory infections (Figure 1b). M. catarralis was present in high abundance in one control, a patient with multiple myeloma who presented with a fever of unknown origin in the setting of prior therapy with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

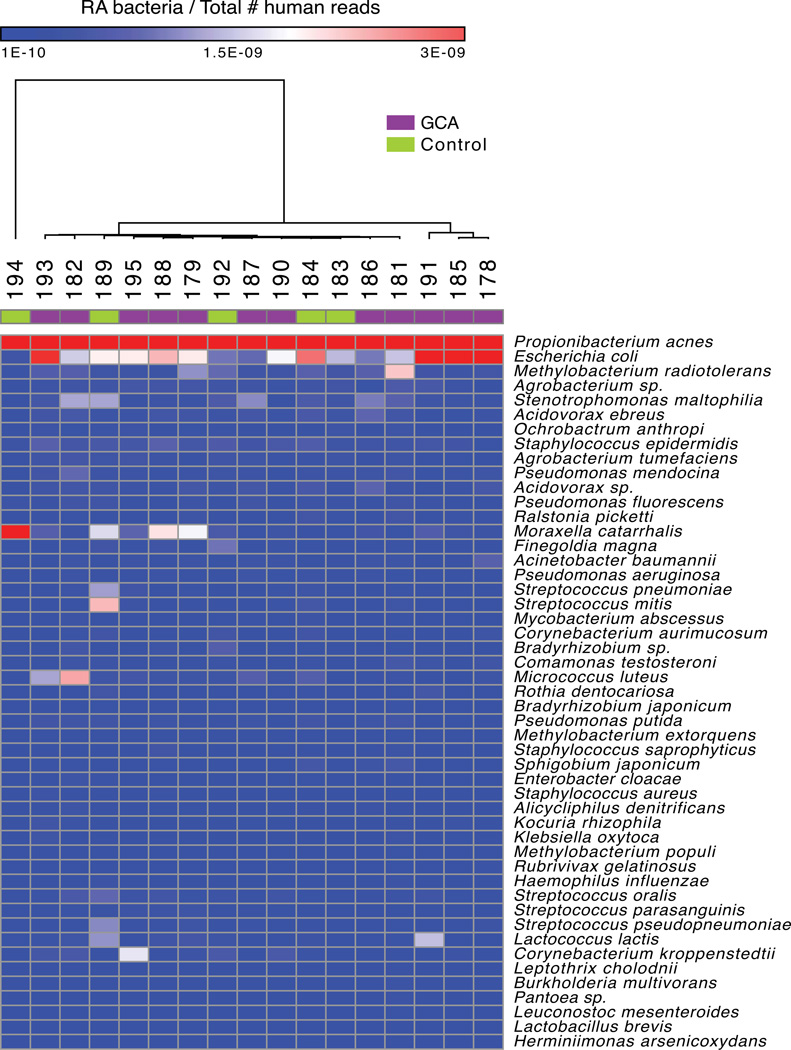

The corrected relative abundance of the 49 most abundant bacteria is presented as a heatmap (Figure 2). Hierarchical clustering was conducted using all available RA data (pairwise average linkage and Pearson’s correlation coefficient; Figure 2) and did not reveal a strongly discernible difference between cases and controls (12). Comparative marker analysis was also performed and did not reveal any significantly enriched bacterial species (False Discovery Rate < 0.1) in cases or controls.

Figure 2. Heatmap representation of the most abundant organisms in the tissue microbiome of GCA and control TA biopsies.

Whole genome sequencing of TA biopsies was followed by microbial taxonomic classification of reads using the PathSeq computational platform. As demonstrated, PathSeq analysis of the GCA microbiome does not show an enrichment of candidate pathogens or other microbes in cases compared to controls. The forty-nine most abundant organisms in cases and controls are shown in the heatmap. The heatmap indicates the relative abundance value for each bacterium listed in each sample (RA values were normalized based on the number of total human reads per sample). Red shading indicates a relatively higher abundance of the given bacterium, white shading indicates intermediate abundance, and blue shading indicates a relatively low abundance of the given bacterium. Hierarchical clustering of cases (noted by a purple box in the top row) and controls (noted by a green box in the top row) was conducted using pairwise average linkage and Pearson’s correlation.

LEfSe analysis was carried out to identify class-wise differences between cases and controls (13). With an LDA effect size cutoff score of 4.0 and a median RA cutoff of 0.5%, no organisms were statistically significantly enriched in cases versus controls.

Discussion

The microbiomes of the GCA cases and the controls in this cohort were not distinctive. Despite routine measures to insure surgical sterility, both cases and controls were dominated by P. acnes and E. coli, well described members of the skin microbiome. The relatively even distribution of sequencing reads between cases and controls indicates that the sample handling and sequencing process did not introduce a class-based bias. Moreover, the GCA cases did not have a notably larger number of non-human reads compared to controls, implying that the abundance of microbes was similar in both groups. Several statistical tests were applied to determine if microbial characteristics of the samples could differentiate cases and controls. Hierarchical clustering, comparative marker and LEfSe analysis did not support differences between the microbiomes of the cases and controls. Finally, none of the previously identified bacterial or viral candidate pathogens was enriched in the GCA cases compared to controls (4, 5, 7, 14). In sum, the data demonstrate that the microbial composition of temporal arteries in GCA patients is similar to those in the control population studied here.

Despite the strong suggestion from our data analysis that a specific microbial trigger or enriched microbial community is not likely to be present in GCA, several issues must be considered when interpreting these results. Limitations of the DNA sequencing approach used here include its inability to detect RNA viruses or microorganisms that have already been cleared by a host immune mechanism. Of note, most of the candidate viral agents identified in previous studies are double stranded DNA viruses, and should have been identified using these methods(4, 14). Our approach is also inherently biased toward abundant organisms and pathogens that are present at the site of clinical inflammation – thus, a greater depth of sequencing may be required to detect a pathogen present in very low quantities and more systemically-focused studies (for example, sequencing of the blood or remote sites of candidate pathogenic triggers) may be indicated. Ideal tissue controls are another significant challenge, as all patients who served as controls in this study had clinical signs or symptoms that were concerning enough to prompt a temporal artery biopsy. Temporal arteries obtained from truly unaffected individuals, for example through an autopsy series, might serve as alternative controls. Lastly, while there is an intrinsic advantage to obtaining cases and controls obtained and processed in a controlled clinical and pathological environment, the generalizability of this single institution study may be limited. In order to overcome these challenges, studies of future multi-center prospective TA collections or evaluation of additional affected tissues (such as the aorta in cases of GCA aortitis) could be considered. Such prospective studies might also be improved by approaches that limit the introduction of skin flora or dermal and epidermal contamination into the surgical specimen.

Notwithstanding these potential limitations, this investigation of TA biopsies of GCA cases and controls did not demonstrate significant differences in the microbiomes of temporal arteries from patients with GCA compared to controls. An unbiased, deep sequencing approach did not identify bacteria or viruses previously reported to be associated with GCA. These results also suggest that unbiased methods for pathogen discovery are preferable to targeted methods that query individual species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from National Cancer Institute (RC2CA148317) (to Dr. Meyerson), the Claudia Adams Barr Program in Basic Cancer Research (Innovative research award to Dr. Bhatt), and the National Science Foundation (Graduate Research Fellowship to Ms. Cai).

Dr. Meyerson has received consulting fees from Foundation Medicine and is a founder of and equity holder in Foundation Medicine.

References

- 1.Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Immune mechanisms in medium and large-vessel vasculitis. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2013;9(12):731–740. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salvarani C, Gabriel SE, O'Fallon WM, Hunder GG. The incidence of giant cell arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota: apparent fluctuations in a cyclic pattern. Annals of internal medicine. 1995;123(3):192–194. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-3-199508010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabriel SE, Espy M, Erdman DD, Bjornsson J, Smith TF, Hunder GG. The role of parvovirus B19 in the pathogenesis of giant cell arteritis: a preliminary evaluation. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1999;42(6):1255–1258. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199906)42:6<1255::AID-ANR23>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell BM, Font RL. Detection of varicella zoster virus DNA in some patients with giant cell arteritis. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2001;42(11):2572–2577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haugeberg G, Bie R, Nordbo SA. Temporal arteritis associated with Chlamydia pneumoniae DNA detected in an artery specimen. The Journal of rheumatology. 2001;28(7):1738–1739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon LK, Goldman M, Sandusky H, Ziv N, Hoffman GS, Goodglick T, et al. Identification of candidate microbial sequences from inflammatory lesion of giant cell arteritis. Clinical immunology. 2004;111(3):286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koening C, Katz BJ, et al. Identification of a burkholderia-like strain from temporal arteries of subjects with giant cell arteritis [abstract]. Abstracts of the 2012 American College of Rheumatology/Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals Annual Scientific Meeting. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64(Suppl)(10):855. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatt AS, Freeman SS, Herrera AF, Pedamallu CS, Gevers D, Duke F, et al. Sequence-based discovery of Bradyrhizobium enterica in cord colitis syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369(6):517–528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kostic AD, Gevers D, Pedamallu CS, Michaud M, Duke F, Earl AM, et al. Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22(2):292–298. doi: 10.1101/gr.126573.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naccache SN, Greninger AL, Lee D, Coffey LL, Phan T, Rein-Weston A, et al. The perils of pathogen discovery: origin of a novel parvovirus-like hybrid genome traced to nucleic acid extraction spin columns. Journal of virology. 2013;87(22):11966–11977. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02323-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kostic AD, Ojesina AI, Pedamallu CS, Jung J, Verhaak RG, Getz G, et al. PathSeq: software to identify or discover microbes by deep sequencing of human tissue. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29(5):393–396. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(25):14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome biology. 2011;12(6):R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salvarani C, Farnetti E, Casali B, Nicoli D, Wenlan L, Bajocchi G, et al. Detection of parvovirus B19 DNA by polymerase chain reaction in giant cell arteritis: a case-control study. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2002;46(11):3099–3101. doi: 10.1002/art.10580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S, Deming CB, Davis J, Young AC, et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science. 2009;324(5931):1190–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1171700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.