Abstract

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have reproducibly associated variants within introns of FTO with increased risk for obesity and type-2 diabetes (T2D) 1–3. While the molecular mechanisms linking these noncoding variants with obesity are not immediately obvious, subsequent studies in mice demonstrated that FTO expression levels influence body mass and composition phenotypes 4–6. Yet, no direct connection between the obesity-associated variants and FTO expression or function has been made 7–9. Here, we show that the obesity-associated noncoding sequences within FTO are functionally connected, at megabase distances, with the homeobox gene IRX3. The obesity-associated FTO region directly interacts with the promoters of IRX3 as well as FTO in the human, mouse, and zebrafish genomes. Furthermore, long-range enhancers within this region recapitulate aspects of IRX3 expression, suggesting that the obesity-associated interval belongs to the regulatory landscape of IRX3. Supporting this, obesity-associated SNPs are associated with expression of IRX3, but not FTO, in human brains. Directly linking IRX3 expression with regulation of body mass and composition, Irx3-deficient mice exhibit a 25–30% reduction in body weight, primarily through the loss of fat mass and increase in basal metabolic rate with browning of white adipose tissue. Furthermore, hypothalamic expression of a dominant negative form of Irx3 reproduces the metabolic phenotypes of Irx3-deficient mice. Our data posit that IRX3 is a functional long-range target of obesity-associated variants within FTO, and represents a novel determinant of body mass and composition.

Noncoding variation in single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within a 47 kb region of high linkage disequilibrium (LD) in introns 1 and 2 of FTO remains the strongest genetic association with risk to polygenic obesity in humans 1–4. Individuals homozygous for risk alleles of the associated SNPs weigh approximately 3 kilograms more than individuals homozygous for non-risk alleles, underscoring the significant phenotypic impact of these common variants 2. Multiple follow-up studies directly implicated FTO as a gene controlling body mass and composition. Null Fto alleles in mice result in lean phenotypes, with reciprocal models overexpressing FTO displaying increased body weight 4–6. Lacking, however, is direct evidence that enhancers within the obesity-associated FTO introns are connected with regulation of FTO expression. Toward that end, expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) analyses have systematically failed to show association between the obesity-associated SNPs and FTO expression in human tissues 7–9.

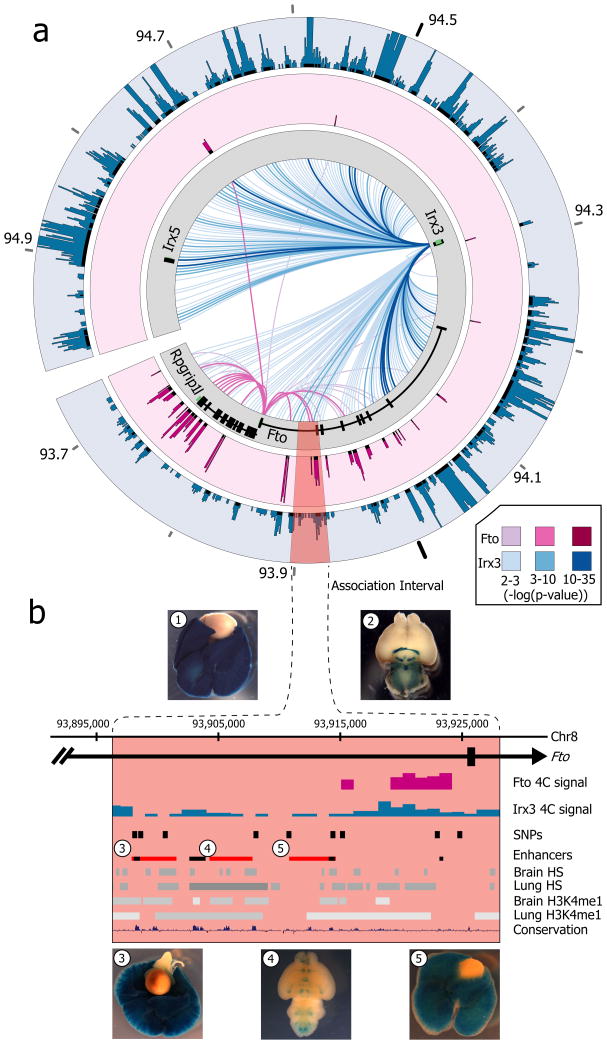

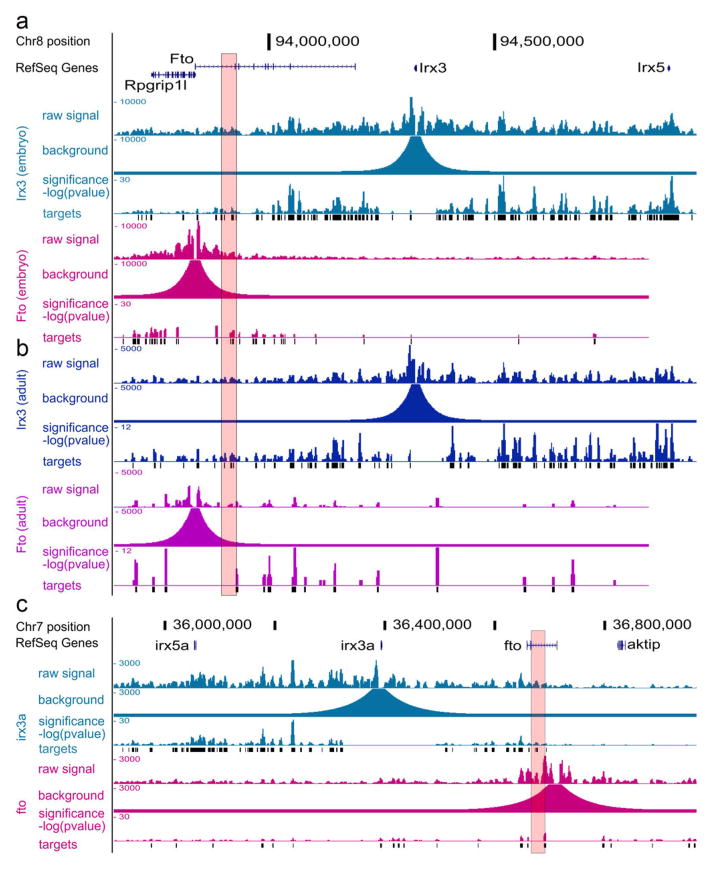

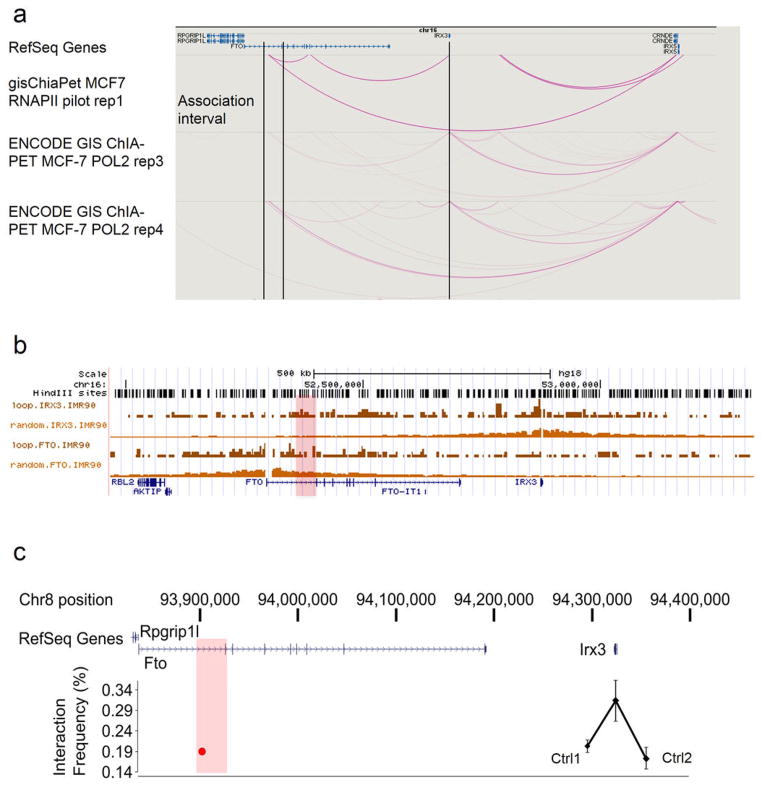

To directly chart the cis-regulatory circuitry within the FTO locus, we used circular chromosome conformation capture followed by high throughput sequencing (4C-seq). We carried out 4C-seq in whole mouse embryos (E9.5) and in adult (8 weeks) mouse brains, since previous work suggest that brain FTO expression modulates metabolic parameters 6, 10. We profiled the genomic interactions with promoters of genes located within a megabase window around the obesity-associated SNPs (mm9, chr8:93,725,000–94,725,000), including Fto and Rpgrip1l, and Irx3, a half-megabase downstream. The difference in interaction patterns among genes was striking (Fig. 1a). The Fto promoter chiefly participates in genomic interactions proximal to the gene promoter. While in mouse embryos these interactions include the obesity-associated intronic region (Fig. 1b), no such interactions are detected in adult mouse brains (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). In marked contrast, the promoter of Irx3 participates in numerous long-range interactions across a broad genomic region encompassing nearly 2 megabases, including robust interactions with the obesity-associated interval within FTO (Fig. 1a). We confirmed these interactions between Irx3 and the Fto obesity-associated region using chromatin conformation capture (3C) in adult mouse brains (Extended Data Fig. 2c). These data suggest the obesity-associated interval is likely part of the regulatory landscape of Irx3. We next inferred that the long-range interactions between the obesity-associated FTO intron and IRX3 represent a conserved feature in vertebrate genomes. Inspecting the human ENCODE dataset, we observe that MCF-7 cells display the same pattern of long-range looping between the obesity-associated interval and IRX3, but not FTO, assayed by ChIA-PET (Extended Data Fig. 2a). This is further corroborated by recent HiC data in human fibroblasts11 (Extended Data Fig. 2b). We also observed a similar pattern of chromatin interactions in zebrafish embryos, assayed by 4C-Seq (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Together, these data posit that the obesity-associated FTO intron is mediating functional interactions with IRX3 in the human, mouse, and zebrafish genomes.

Figure 1. Long-range interactions in the IRX3/FTO locus.

a, Mouse embryo 4C-seq interactions emanating from each promoter are displayed as links across the circle (darker link implies greater significance). Outer plots show significance of interactions above background (-log(p-value)). The obesity-associated interval is highlighted red. b, Magnified view of the association interval. Contained within are the orthologous locations of obesity-associated SNPs (black pips), and epigenetic marks associated with regulatory elements. Endogenous Irx3 expression is shown (1. lung, 2. brain) in Irx3lacZ knockin mouse. Three enhancers (rectangles 3–5) drive reporter expression in lungs (3, 5) and brain (4). Other enhancers17 are shown in black.

Having uncovered evidence of direct looping between FTO intronic regions and IRX3, we next showed that enhancers within the obesity-associated interval possess functional characteristics compatible with IRX3 expression. We observed that the degree of evolutionary conservation in noncoding sequences of the FTO-IRX locus (chr16:53731249–54975288) places it on the top 2% of similarly-sized genomic intervals, suggesting the presence of many functional noncoding elements spread over the region (see Methods). More specifically, ENCODE data suggest that the 47-kb obesity-associated interval is fraught with cis-regulatory elements, evidenced by an abundance of enhancer-associated chromatin marks, DNase hypersensitive sites, and transcription factor binding events across this genomic region (Fig. 1b). We tested three human DNA fragments from the 47-kb obesity-associated region for their putative enhancer properties using an in vivo mouse reporter assay. These fragments overlap enhancer-like chromatin marks in multiple cell lines. All three fragments displayed enhancer activity in neonatal (P0–P1) mice. Interestingly, two of the fragments drove strong reporter gene expression in lungs (Fig. 1b). Irx3 is highly expressed during lung development (Fig. 1b) 12, 13, whereas Fto expression in lungs is limited (Extended Data Fig. 3a and references 2, 14–16). Consistent with our data, a previous report has shown that the FTO obesity-associated region contains enhancers that drive Irx3-like expression in zebrafish 17.

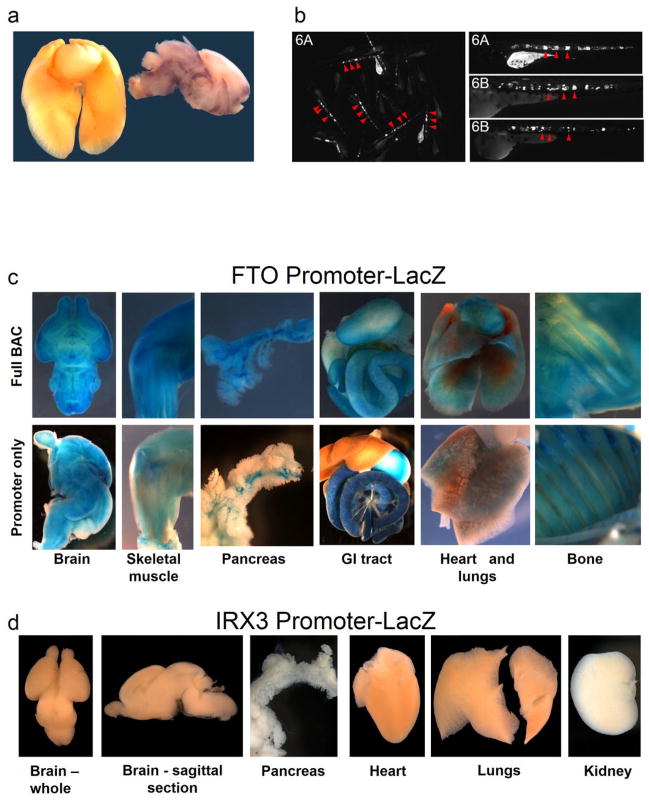

Our data suggest that the regulatory landscape of IRX3 spreads over megabase distances, whereas FTO expression is primarily regulated by regions proximal to its promoter. To test this, we engineered a human Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) spanning 162 Kb of the FTO locus, including its promoter and the 47-Kb obesity-associated region (Extended Data Fig. 3). We recombineered a reporter cassette at the FTO translation start and generated transgenic mice harboring the engineered BAC. Transgenic mice expressed the reporter gene in multiple tissues, recapitulating the endogenous expression pattern of FTO14. We next determined that a 1.2 Kb region corresponding to the FTO promoter is sufficient to recapitulate most of the FTO expression pattern (Extended Data Fig. 3). In contrast, a 2.8-kb region corresponding to the IRX3 promoter does not recapitulate any of the endogenous expression patterns of IRX3, suggesting that IRX3 expression relies on long-range cis-regulatory elements. A total of 15 human sequences in the broader FTO-IRX locus have been characterized as in vivo enhancers in mouse 17, 18, driving reporter expression in Irx3-expressing tissues, including eye, limb, brain, neural tube, and branchial arches 12, 19 (Supplementary Table 2). While these enhancers lie outside the obesity association interval, they are consistent with our chromatin looping data pointing to a broad Irx3 regulatory landscape, extending into Fto. Further supporting these findings, the genomic interval spanning FTO and IRX3 has been proposed to be part of a single genomic regulatory block, based on the presence of extended synteny across deep phylogenies and a high density of highly conserved noncoding elements 17, as well as patterns of CTCF binding and chromatin interactions 20. Under these models, our data support the notion that the broad expression patterns of FTO are primarily regulated by elements proximal to the promoter, and that IRX3 is endowed with an ancient, extensive cis-regulatory circuitry extending into FTO.

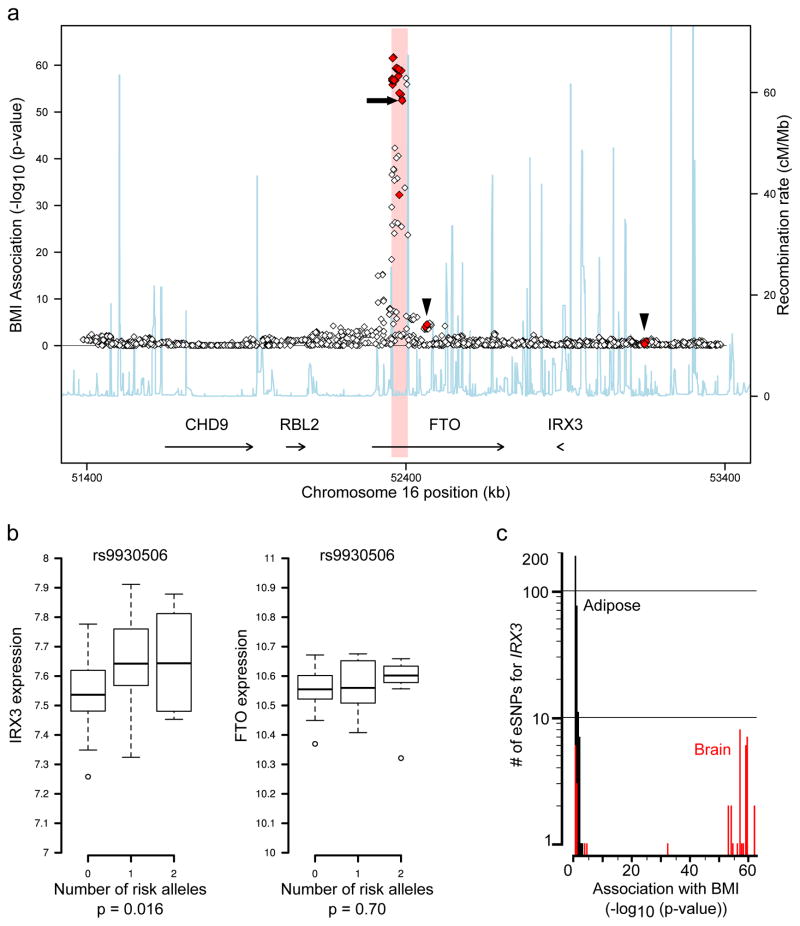

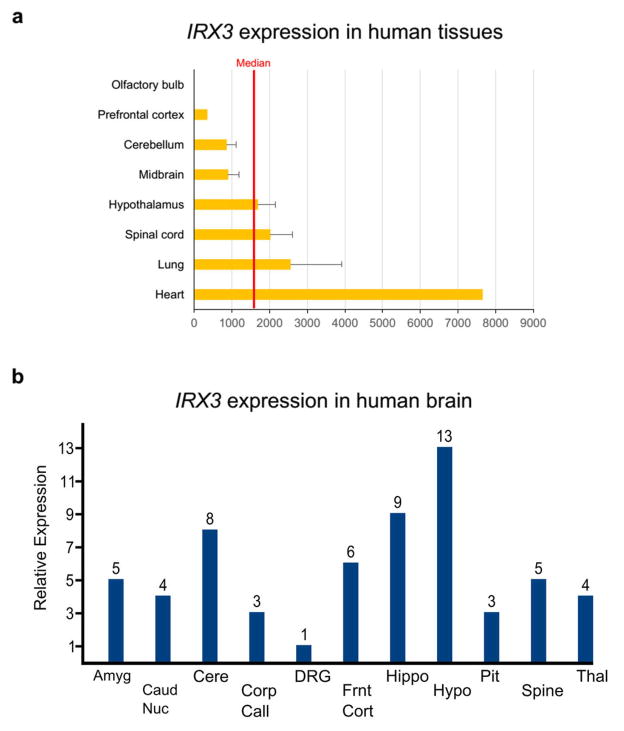

We next determined that gene expression studies in human brains corroborate our chromatin looping data, showing that the obesity-associated SNPs are associated with expression levels of IRX3, but not FTO. Our data and that of others 17 (Fig. 1b) demonstrate that the obesity-associated SNPs overlap several in vivo enhancers, raising the possibility that allelic variants may disrupt enhancer activity and alter expression of their target gene(s). To test this, we carried out eQTL mapping in human brain samples. FTO and IRX3 are highly expressed in multiple regions of the brain including cerebellum and hypothalamus (Extended Data Fig. 4). Utilizing a dataset of 153 brain samples from individuals of European ancestry 21, represented by cerebellum, we found significant association between 11 SNPs previously associated with increased body mass index (BMI), and expression of IRX3, but not FTO (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 3). These common SNPs have minor allele frequencies ranging from 42.5 to 47.5% and are in strong LD with each other (Extended Data Fig. 5). In all cases, such as for SNP rs9930506 (Fig. 2b), the allele associated with increased BMI is also associated with increased IRX3 expression. Further analysis, utilizing the GIANT Consortium dataset of SNPs associated with BMI in 249,796 individuals 22, reveals that among SNPs significantly associated with IRX3 expression in brain or adipose tissue, only those associated with IRX3 in brain show highly significant associations with BMI (Fig. 2c). Taken together, our data directly ties the noncoding genetic variation within FTO to tissue-specific modulation of IRX3, but not FTO, expression in human brain.

Figure 2. BMI-associated SNPs are eSNPs for IRX3, not FTO, expression in human brain.

a, SNPs associated with BMI in the FTO locus. 43 SNPs associated with IRX3 expression (eSNPs) are shown in red, including 11 also associated with BMI. No SNPs are associated with FTO expression (p-value>0.05). Arrowheads: IRX3 eSNPs outside the obesity-associated region (pink); arrow: rs9930506. b, In cerebellum, the allele of rs9930506 associated with increased BMI (risk allele) is correlated with increased IRX3 expression and not with FTO expression. c, Histogram plotting the number of SNPs associated with IRX3 expression in adipose (black) and brain (red) (y-axis) by the significance of their association with BMI (x-axis). Full statistical details in Methods.

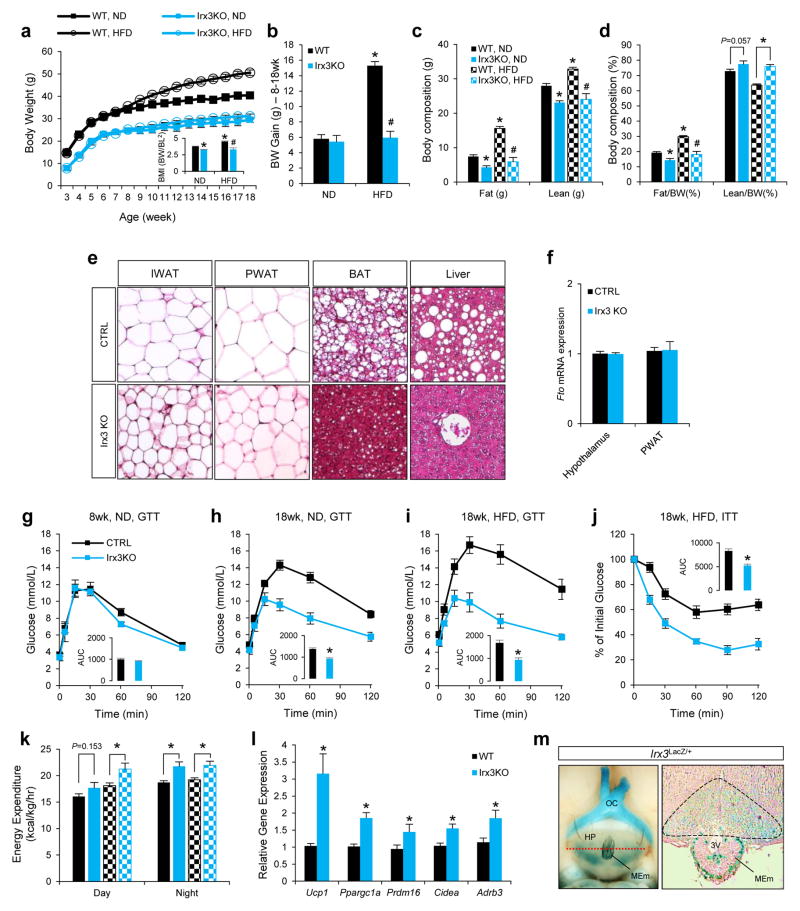

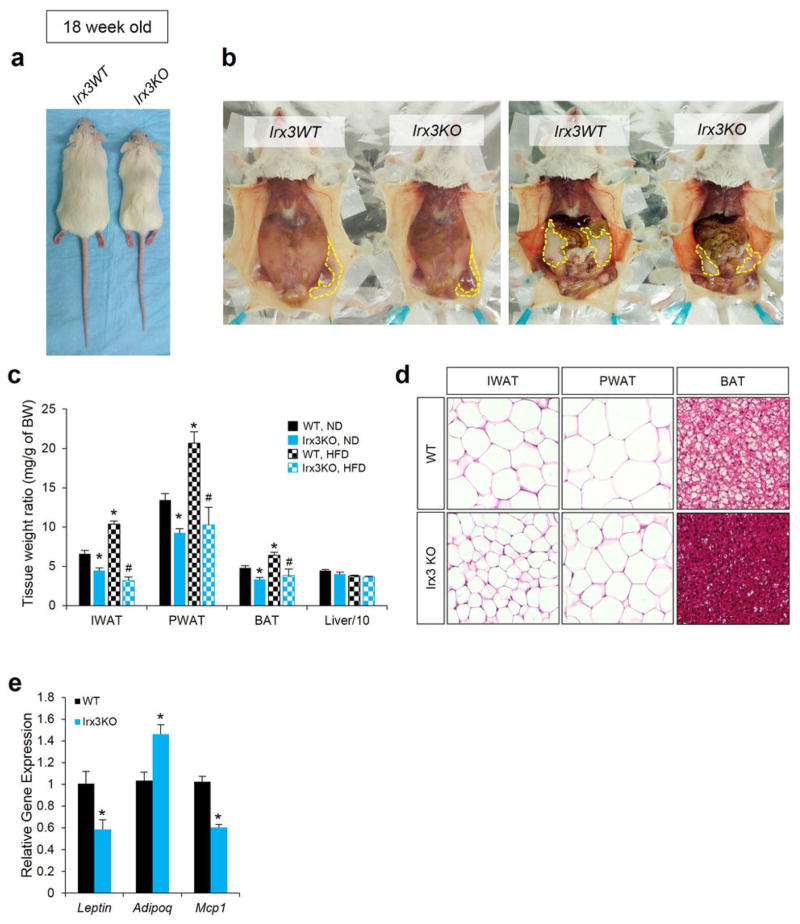

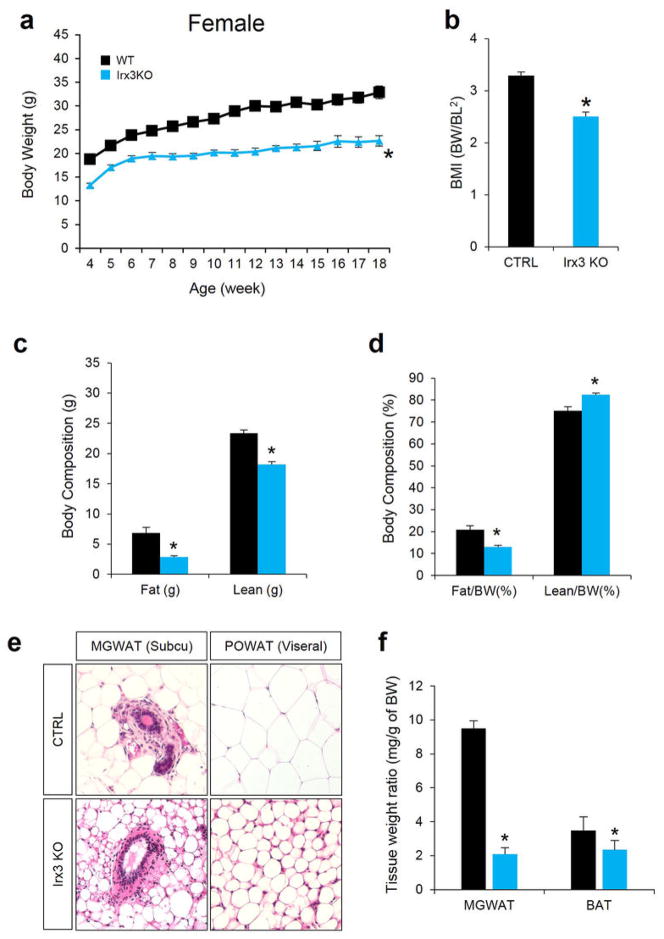

Next, we exploited animal models to determine a potential role for IRX3 expression in the regulation of BMI and/or metabolism. Mice homozygous for an Irx3 null allele (Irx3KO) are viable and fertile, with no evidence of embryonic lethality. We observed a 25–30% reduction of body weight in Irx3KO mice compared to control littermates (wild-type; WT), independent of gender (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 6a, b and 7a, b). This difference becomes more pronounced if animals were subjected to a high-fat diet (HFD), with Irx3KO animals showing no significant body weight gain, contrasting to a 63% increase in control animals (Fig. 3a, b). Importantly, the percentage of fat mass in Irx3KO mice was significantly reduced without marked change of the lean mass ratio (Fig. 3c, d, and Extended Data Fig. 7c, d). Irx3KO mice exhibit marked reduction in adiposity with smaller fat depots as well as reduced adipocyte size (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 6b–d, 7e, f). These results were confirmed by differential gene expression of adiposity markers (i.e. leptin, adiponectin, and mcp1) in the Irx3KO perigonadal white adipose tissue (PWAT) (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Importantly, Fto expression was not altered in Irx3KO hypothalamus or PWAT, suggesting that the lean phenotype of Irx3KO mice is not associated with Fto (Fig. 3f). Since Irx3KO mice were resistant to HFD-induced obesity and metabolic disorder, such as hepatosteatosis (Fig. 3e), we examined glucose homeostasis by performing glucose tolerance tests (GTT) and insulin tolerance test (ITT) at different time points in the presence or absence of HFD. In 8-week old mice, no difference in GTT was found (Fig. 3g). While aging and HFD led to glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in WT mice, Irx3KO mice showed none of these metabolic phenotypes (Fig. 3g–j).

Figure 3. Irx3 deficient mice are leaner and are protective against diet-induced obesity.

a, Body weight in wild-type (WT) and Irx3KO mice fed normal (ND) or high-fat diet (HFD). b, Weight gain in ND or HFD. c, Fat and lean mass in WT and Irx3 KO mice. d, Fat and lean mass ratio as a percentage of body weight. e, Sections of inguinal white adipose tissue (IWAT; subcutaneous), perigonadal WAT (PWAT; visceral), brown adipose tissue (BAT), and liver from HFD-fed mice. f, Fto mRNA expression in hypothalamus and PWAT of Irx3 KO and WT mice.g-i, Glucose tolerance tests (GTT) in WT and Irx3 KO mice. Inset graphs show area under curve (AUC). j, Insulin tolerance test (ITT) in HFD-fed mice. k, Energy expenditure on ND- and HFD-fed mice. l, Gene expression in PWAT. m, Irx3 expression in the arcuate nucleus and median eminence. Left panel shows a ventral view of whole-mount stained brain. A dashed red line indicates the position of cross-section, displayed in the right panel. β-gal stained area in arcuate nucleus is marked by black line. HP, hypothalamus; OC, optic chiasm; MEm, median eminence; 3V, third ventricle. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. *, P < 0.05 compared to control group. See additional statistical detail in Methods.

Indirect calorimetric analysis showed higher energy expenditure in Irx3KO mice (Fig. 3k and Extended Data Fig. 8a, b & e). Importantly, Irx3KO mice show up-regulation of brown adipocyte markers in PWAT, including Ucp1, Ppargc1a, Prdm16, and Cidea, as well as increased expression of Adrb3 encoding the β3-adrenergic receptor, suggestive of elevated sympathetic activation (Fig. 3l). Furthermore, we found a significant increase of Ucp1 expression in the brown adipose tissue (BAT) of Irx3KO mice (Extended Data Fig. 8e, f). WAT predominantly stores excessive calories and its accumulation causes obesity, while brown adipose tissue (BAT) dissipates energy (lipids and glucose) and has been the focus for potential development of novel therapeutic strategies to treat obesity and diabetes. Our data suggest that “browning” of WAT by higher sympathetic tone and activation of BAT might lead to increased energy expenditure in Irx3KO mice and partially account for their leanness and protection from diet-induced obesity.

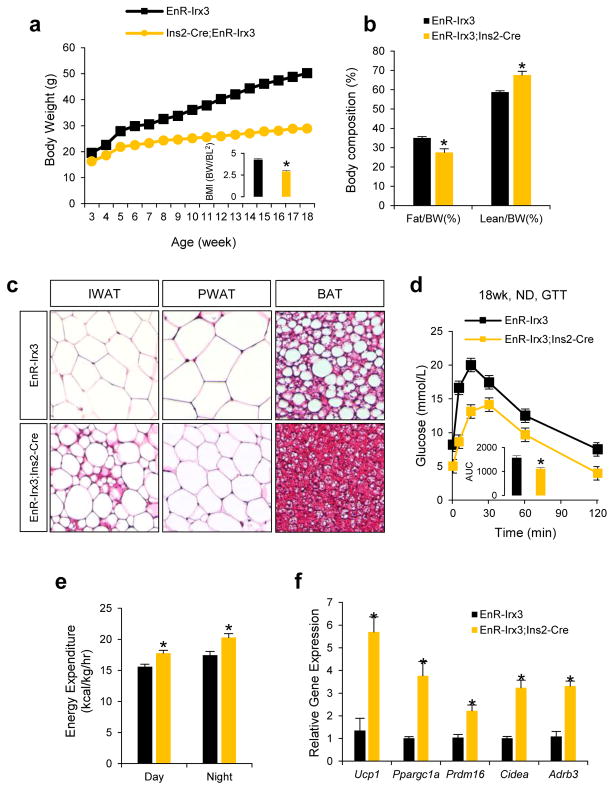

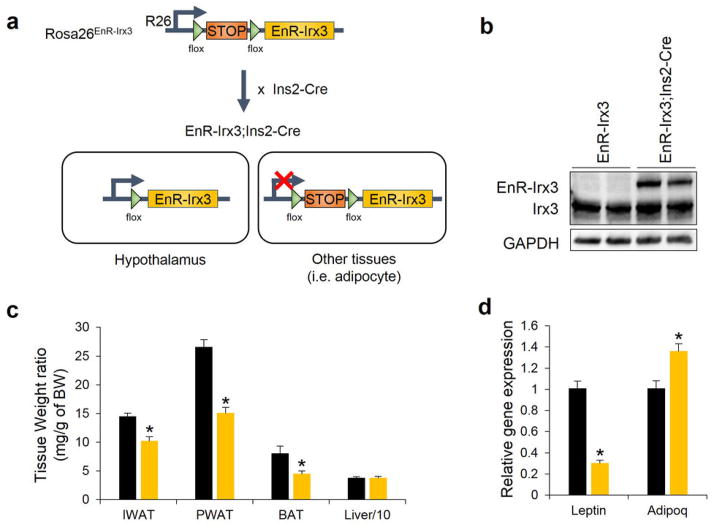

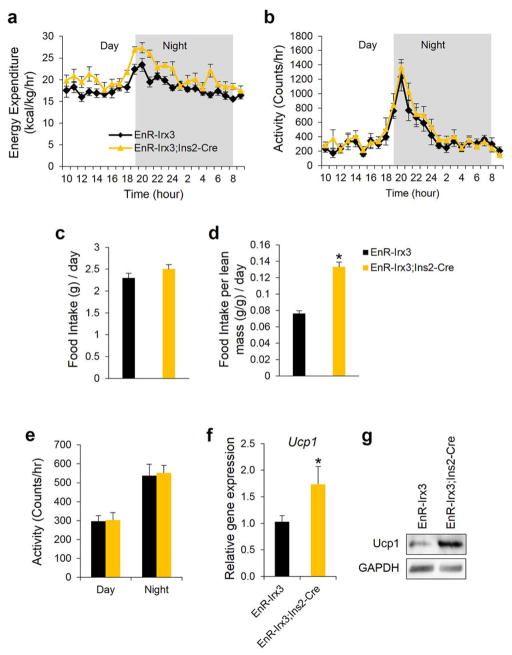

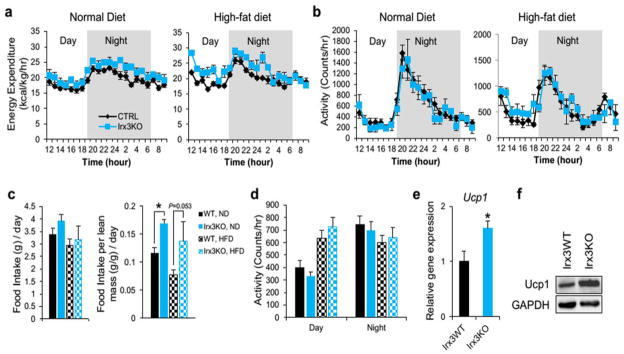

Browning of WAT by increased sympathetic activity is a phenomenon controlled by hypothalamic circuits integrating central and peripheral metabolism regulation. Our human eQTL data suggest that the obesity-associated SNPs are associated with IRX3 expression in brain. We determined that Irx3 is expressed in the arcuate nucleus and median eminence of the hypothalamus, two critical regions involved in the regulation of energy homeostasis (Fig. 3m)23,24. To investigate a possible role of Irx3 expression in the hypothalamus mediating the body composition and energy homeostasis phenotypes in Irx3KO mice, we utilized Rosa26EnR-Irx3 conditional transgenic mice expressing a dominant negative form of Irx3 (EnR-Irx3) by crossing with Ins2-Cre (Extended Data Fig. 9a, b)23,25. This design allows for disrupting Irx3 function while preserving the architecture of genomic interactions between the Irx3 promoter and long-range regulatory sequences including the Fto obesity-associated region. Remarkably, EnR-Irx3;Ins2-Cre mice phenocopy the physiological, histological, and molecular metabolism phenotypes of germline Irx3KO mice (Fig. 4a–d and Extended Data Fig. 9c, d). Energy expenditure was significantly higher in EnR-Irx3;Ins2-Cre mice with similar food intake and locomotor activity (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 10a–e). Notably, these mice also exhibited “browning” of WAT as well as activation of BAT (Fig. 4f and Extended Data Fig. 10f–g). Together, our data support the notion that the hypothalamic expression of Irx3 regulates energy homeostasis and body composition.

Figure 4. hypothalamus-specific dominant negative Irx3 mice recapitulate the metabolic phenotype of Irx3 deficient mice.

a, Body weight of control (EnR-Irx3) and mutant mice (EnR-Irx3;Ins2-Cre) fed normal diet. b, Fat and lean mass ratio as a percentage of body weight.. c, H&E-stained sections of IWAT, PWAT and BAT. d, Glucose tolerance test. e, Energy expenditure corrected for lean mass (kcal/kg/hr). f, qPCR in PWAT in control and mutant mice. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. *, P < 0.05 compared to control group. Additional detail in Methods.

Our results do not dispute the notion emerging from animal models that Fto is also a regulator of body mass and composition. The functional link between FTO and body mass regulation originated from animal models, unequivocally demonstrating that variation in FTO expression results in variation in body mass phenotypes. But to assess the null expectation that genetic manipulations in mice may result in variation in these parameters, we searched among 7,556 targeted mouse gene knock-out models for evidence of alterations in body size, mass, and growth (See Methods). Nearly one third (2,166; 29%) of gene knock-outs in mice show alteration of these phenotypes, underscoring that animal models alone are not sufficient to definitively establish a functional relationship between a given gene and long-range noncoding variants (Supplementary Table 4). It is the aggregate of our data on chromatin looping, patterns of in vivo enhancer function, human eQTL mapping and mouse model data that collectively place IRX3 as an important target gene of the genetic association with human obesity. These observations have direct implication on how to interpret the associations characterized for thousands of noncoding variants with human disease and related quantitative traits. We observe more than 150 genomic regulatory blocks, similar to that containing FTO and IRX3, overlapping with noncoding SNPs associated with human disease and complex traits in GWAS (Methods and Supplementary Table 5), highlighting the need for a careful experimental pipeline to define the target gene(s) for each disease-associated noncoding SNP.

Our data posit that the obesity-associated SNPs within FTO are functionally connected with regulation of IRX3 expression, and that IRX3 is an important determinant of body mass and composition. IRX3 encodes a transcription factor highly expressed in brain. While our data represent the first demonstration of the intersection of IRX3 biology with body mass composition and metabolism, previous work identified IRX3 overexpression in adipocytes as a hallmark of the molecular switch seen in patients after profound weight loss following bariatric surgery26. These data indicate that IRX3 may have important roles regulating metabolism beyond the ones we describe associated with Irx3 expression in hypothalamus. Future investigations will determine the precise molecular mechanisms by which IRX3 regulates metabolic parameters.

Methods

3C

3C assays were performed as referred in27. Mouse brain tissue was processed to get single cells samples. 10 millions isolated cells were treated with lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM NaCl, 0.3% IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich, I8896), 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete, Roche, 11697498001)) and nuclei were digested with HindIII endonuclease (Roche, 10798983001). Subsequently, DNA was ligated with T4 DNA ligase (Promega, M1804). A set of locus specific primers (see table) was designed with the online program primer3 v. 0.4.028, each one close to a HindIII restriction site. These primers were used to make real time quantitative PCRs using a BioRad CFX96 Real Time System with SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (BioRad 172-5203), in order to measure the relative enrichment in each ligation product. The primer designed within the LD-block was used as fixed primer. The quality of all primer pairs was measured using serial dilutions of a BAC DNA that encompass the regions of interest (RP23-268O10, RP23-96F3). PCR values were normalized by means of control primers designed in the Ercc3 gene locus. The average of four independent experiments was graphically represented.

4C-Seq

4C-seq assays were performed as previously reported27, 29–31. Whole embryos (9.5 days of development) or whole adult (8 weeks) mice brains (both strain CD-1; Charles River Labs) were processed to get approximately 10 million isolated cells, which were treated with lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM NaCl, 0.3% IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich, I8896), 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete, Roche, 11697498001)). Nuclei were digested with DpnII endonuclease (New England Biolabs, R0543M) and ligated with T4 DNA ligase (Promega, M1804). Subsequently, Csp6I endonuclease (Fermentas, Thermo Scientific, FD0214) was used in a second round of digestion, and the DNA was ligated again. Specific primers were designed near each gene promoter with primer3. Viewpoint fragend coordinates were as follows: mFTO: chr8:93837310–93837724; mIrx3: chr8:94325277–94326009. Illumina adaptors were included in the primers sequence32. 16 PCRs were performed with Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche, 11759060001) for each viewpoint, pooled together and purified using High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Roche, 11732668001). Quanti-iT™ PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, P11496) was used in order to measure sample concentration, and then they were sent for deep sequencing. 4C-seq data were analysed, with some changes, as described in 30.

Briefly, raw sequencing data were de-multiplexed and aligned using either the Mouse July 2007 (NCBI37/mm9) or Zebrafish December 2008 (Zv8/danRer6) assembly as the reference genome. Reads located in fragments flanked by two restriction sites of the same enzyme, or in fragments smaller than 40 bp were filtered out. Mapped reads were then converted to reads-per-1kb-bin units, and smoothed using a running mean 5-fragment window algorithm. To calculate the statistically significant targets for each viewpoint, a background theoretical model was calculated as the exponential fit curve of the average signal of 61 4C-Seq different samples33–35. The p-value for each bin was calculated by means of Poisson probability function. Smoothed data were uploaded to the UCSC Browser36 for visualization and plotted using the browser and Circos37. For plotting, statistically significant targets were defined as p<0.01. Data was submitted to GEO under accession GSE52830, and can be accessed online at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=elcraaeglhstzwz&acc=GSE52830.

Primers used for 3C experiments

| 3c_mouse_LDBlock | TGGTCTCGGGTATCTTGTCC |

| 3c_mouse_Irx3_control1 | TCGCTCCTAGTGAGACTTTC |

| 3c_mouse_Irx3_promoter | TGATGTTGGTTCCTTACTAGG |

| 3c_mouse_Irx3_control2 | TCCACAGAAACATCTGACG |

| 3c_mouse_Ercc3-1 | TGACCTCCACACTCCTGAC |

| 3c_mouse_Ercc3-2 | ATGCGCAATTAGAAACTGC |

Primers used for 4C-Seq experiments

| 4c_mouse_Fto_R | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCC GATCTCATATTGCTCTGGATGCAGATC |

| 4c_mouse_Fto_NR | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGAACTACCCTTCCCAGAATGC |

| 4c_mouse_Irx3_R | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGAT CTCCGCCGCGGAGCAGATC |

| 4c_mouse_Irx3_NR | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGATGGAGTCGCCAATCACC |

| 4c_zebrafish_Fto_R | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGAT CTCCTCTCACTGTCATCCGATC |

| 4c_zebrafish_Fto_NR | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGACTACATTTTATGTCAGTTTCGGG |

| 4c_zebrafish_Irx3a_R | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGAT CTCCTACCGGATTACTCTACAGATC |

| 4c_zebrafish_Irx3a_NR | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAAAAACGCCCAGAAGACTGAC |

Note: R = read, NR = nonread

ENCODE ChIA-PET

Publicly-available data for the breast cancer MCF7 cell line, generated by as part of the ENCODE project38 were downloaded from and visualized with the WashU EpiGenome Browser39 (http://epigenomegateway.wustl.edu/browser/). Li and colleagues40 performed ChIA-PET to capture long-range chromatin interactions associated with RNA polymerase II.

Locus conservation

To assess the level of high-level conservation of the FTO/IRX5 locus, we used phastCons41 elements and scores as a measurement of conservation.

High-scoring phastCons elements (LOD > 680, top 1%) cover 3% (38,040/1,244,409 bp) of the genomic space that includes FTO and IRX5 (hg19, chr16:53731249–54975288), whereas on average, only 0.5% +− 0.6 of genomic intervals with the same length are occupied by such high-scoring phastCons elements. Genomic intervals of the same size of the FTO/IRX3 locus were generated every 10kb for each chromosome. The FTO/IRX5 is at the top 1% intervals containing high-scoring phastCons elements.

Similarly, in the FTO/IRX5 interval, 9% of the base pairs have phastCons score above 0.9 (range: 0.0–1.0), whereas 14,164 intervals from all chromosomes of the same size offset by 200kb contain only 3.8% +− 1.9 of such high-scoring base pairs. At 9%, the FTO/IRX5 is at the top 2% intervals with the most conserved base pairs.

These results indicate that the FTO/IRX5 interval contains significantly more highly conserved base pairs than most genomic loci.

Enhancer reporter constructs, including the modified BAC, were created as previously reported42. The human (NCBI37/hg19) genomic coordinates of the elements cloned are: FTO-1: chr16:53800270–53805184; FTO-2: chr16:53808432–53813121; FTO-3: chr16:53816312–53821148. FTO-promoter: chr16:53736860–53738096; IRX3-promoter: chr16:54319963–54322782. BAC RP11-261B9 was modified by inserting a lacZ-Amp cassette in place of the 36 nucleotides in exon 1 at chr16:53,738,097–53,738,132. This homologous recombination was facilitated by using the following homology arms: FTO-hArm1: chr16:53738047–53738096; FTO-hArm2: chr16:53738133–53738182.

Mouse in vivo transgenic reporter assays were performed as previously reported45

in situ hybridization assays were performed according to standard protocols43. The full length mouse Fto CDS used as riboprobe template was from IMAGE clone 5708558 (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia).

Gene Expression in Human Tissues

For the eQTL analyses, we used cerebellum44 (n = 153; publicly available in GEO: GSE35974) and adipose45 (n=62; publicly available in GEO: GSE40234); details of the samples, the quality control procedure and the normalization approach used were previously described21. For adipose, the samples were chosen to be at the tails of the distribution of insulin sensitivity matched on age, gender and natural log of BMI. Because the adipose samples included individuals of African ancestry, we performed principal component (PC) analysis and tested each marker in the locus for the additive effect of allele dosage on the residual expression phenotype (IRX3 and FTO) after adjusting for the PCs (n=2). Similarly, for cerebellum, we performed linear regression on the residual expression phenotype (IRX3 and FTO) after adjusting for sex and pH to evaluate the additive effect of allele dosage at each marker in the locus; the non-diseased samples (obtained from the Stanley Medical Research Institute) included in the analysis were of European descent and thus the PCs were not used to generate the residual expression. Significance (p-value) was evaluated using the t-statistic from the regression.

eSNP Association with BMI

We downloaded genome-wide association data from the Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits45 (GIANT) consortium website (http://www.broadinstitute.org/collaboration/giant/index.php/GIANT_consortium_data_files#BMI_.28download_GZIP.29). We extracted the p-values for those SNPs in the locus with significant association (p<0.05) with IRX3 or FTO expression in adipose or cerebellum. We plotted the distribution of association p-values for these expression-associated SNPs (eSNPs). rs9930506 is highly associated with BMI (p=1.41e-53, N=123541). Recombination rates are estimated from the International HapMap Project.

Statistical Analyses were done in the R statistical software (http://cran.r-project.org/). Regional plots were done by repurposing an R script retrieved from the Broad Institute (http://www.broadinstitute.org/diabetes/scandinavs/figures.html).

Mice

All animal experimental protocols approved by Animal Care Committee of the Toronto Centre of Phenogenomics conformed to the standards of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. Irx3-deficient (Irx3KO) mice 47 and Ins2-Cre mice 48 were described previously. Rosa26EnR-Irx3 conditional transgenic mice (EnR-Irx3) was generated using pROSA26PA gene-targeting vector as previously described 49. Mice were maintained on 12-hour light/dark cycles and provided with food and water ad libitum. For diet-induced obesity studies, 8 week old male mice were subjected to 45% high-fat diet (Research Diets) for 10 weeks. Body weight was measured every week from 4 to 18 weeks of age, and body composition was analyzed using a EchoMRI device (Echo Medical Systems) at 18 weeks of age. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing body weight (g) by body length (mm) squared (BMI = body weight/body length2).

Metabolic phenotyping experiments

Energy expenditure was evaluated via indirect calorimetry (Oxymax System, Columbus Instruments) over periods of 24 hour. Briefly, energy expenditure was calculated by multiplying oxygen consumption (VO2) by the calorific value (CV = 3.815 + 1.232 × respiratory exchange ratio) and corrected by lean mass. Locomotor activity and food intake were also measured simultaneously. For glucose and insulin tolerance tests, mice were subjected to intraperitoneal bolus injection of glucose (1mg/g of body weight) or insulin (1.5mU/g) after fasting for overnight (14–16 hours) or 6 hours with water ad libitum, respectively. Blood glucose levels were measured at the indicated intervals. For histological analysis, tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. 5 μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Irx3 expression in brain and lung was examined using Irx3lacZ knockin mice with beta-galactosidase staining.

Gene and protein expression analyses

Total RNA was extracted from fat tissues or hypothalamus using RNeasy Lipid Tissue Kit (Qiagen), and cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of RNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with oligo(dT). Gene expression assay was conducted using SYBR Green methods on Viia7 (Applied Biosystems), and relative Ct values were normalized by β-actin. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described 50. The same amount of protein extracted from hypothalamus or brown adipose tissues was loaded, which was confirmed by β-actin as a loading control. Antibodies used are as follows: Ucp1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Irx3 (generated in-house), and β-actin (Calbiochem).

Statistics

All results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical significance of differences among groups was determined by Student’s t-test or ANOVA with post hoc analysis, Student-Newman-Keuls using Sigma Stat (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Differences at P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*, P < 0.05 vs. WT or control; #, P < 0.05 vs. WT, HFD). Following numbers of mice/samples were used for comparison; Body weight measurement for Irx3 mice (ND, WT/KO: n = 32/25; HFD, WT/KO: n = 12/7) and EnR-Irx3 mice (control/mutant: n = 9/12); Body composition analysis for Irx3 mice (ND WT/KO: n = 21/12; HFD WT/KO: n = 8/5) and EnR-Irx3 mice (control/mutant: n = 9/12); Glucose tolerance test for Irx3 mice (ND 8wk, WT/KO: n = 8/5; ND 18wk, WT/KO: n = 10/6; HFD 18wk, WT/KO: n = 12/7) and EnR-Irx3 mice (control/mutant: n = 5/8); Insulin tolerance test for Irx3 mice (WT/KO: n = 12/7); Indirect calorimeter analysis for Irx3 mice(ND WT/KO: n = 7/5; HFD WT/KO: n = 8/4) and EnR-Irx3 mice(control/mutant: n = 5/7), and Gene expression analysis for Irx3 mice (WT/KO: n = 10/7) and EnR-Irx3 mice (control/mutant: n = 5/7).

Mouse Body Mass Phenotypes

To calculate the fraction of knockout mice that display a phenotype affecting body mass, we consulted the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) database51.

First, to determine the number of gene knockouts that result in a body mass phenotype, we needed to define a more precise phenotype. The Mammalian Phenotype Ontology52 (http://www.informatics.jax.org/searches/MP_form.shtml) specifies a controlled vocabulary by which all mice in the MGI database are classified. Within this framework, (we believed) the most applicable is “abnormal postnatal growth/weight/body size” (MP:0002089).

Next, we crafted a query using the MouseMine portal53 (http://www.mousemine.org) to access the MGI database, using MP:0002089 as the search criteria in the “Mammalian phenotypes --> Mouse genotypes” template (http://www.mousemine.org/mousemine/template.do?name=MPhenotype_MFeature&scope=all). We asked for all targeted alleles on chromosomes 1–19, X and Y, reasoning that many non-targeted (i.e. random, chemical and radiation-induced) mutations have not been precisely mapped, making it difficult if not impossible to ensure that they are not counted multiple times. Also, in the context of our study, we are discussing the chance that a targeted knockout would give a specific phenotype, so these types of alleles are most relevant. Finally, we excluded alleles present only as cell lines, resulting in 2166 unique genes.

To determine the total number of targeted mutations present in the MGI database, we performed a search identical to that above but omitting the MP:0002089 term, resulting in 7556 unique genes.

Genomic Regulatory Blocks

Genomic regulatory blocks are regions under strong selection that contain a number of syntenic highly conserved sequences, believed to regulate a syntenic target gene (“anchor gene”, the gene that is the raison d’être of the GRB). There are different approaches to determine GRBs, usually identifying syntenic genes and non-coding conserved regions that span a region and determining the boundaries of the region.

GWAS identified SNPs that might affect non-coding regulatory elements that, by their turn, regulate specific target genes. Assignment of regulatory elements to targets is still a challenge, the simplest method being to assign them to the nearest gene. In the case of FTO, because the GWAS SNP occurs in an FTO intron, this gene was considered to be the target.

The notion put forward here is that when regulatory elements occur within a GRB, which is the case for FTO/IRX3/IRX5, it is likely that they target the anchor gene (IRX3/IRX5), given its importance. Supplemental Table 5 contains an annotation of GRBs and their anchor genes and the GWAS SNPs within the GRB as well as annotation regarding whether the nearest gene is the anchor gene or not. In those cases in which the nearest gene differs from the anchor gene, we propose that the anchor gene be used as the putative target and additional experimentation as shown in this work should be performed to precisely determine which is the target gene for the GWAS-affected regulatory element.

Genomic regulatory blocks were obtained from UCNEbase (http://ccg.vital-it.ch/UCNEbase/)54. Human UCNE clusters (hg19) were downloaded from http://ccg.vital-it.ch/UCNEbase/data/download/clusters/hg19_clusters_coord.bed and are referred here as GRBs.

The hg19 GWAS catalog from the UCSC Genome browser was downloaded and the tagging SNPs contained in GRBs with more than 1 gene (making SNP assigning doubtful) were kept for further annotation. SNPs occurring in exons were removed. The nearest gene was considered to be the RefSeq gene whose transcription start site was the nearest, or the gene where the SNP is contained.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Long range interactions in mouse and zebrafish.

4C-seq data for the Irx3/Fto locus, visualized with the UCSC genome browser. a, Data (also shown in the circular plot in Fig. 1) generated using whole mouse embryos (E9.5), showing the frequency of interactions with the promoter of Irx3 (blue, top) or Fto (magenta, bottom). The background signal corrects for the strong correlation between (non-specific) ligation events and the linear distance along the chromosome. Poisson statistical significance (-log (p-value)) of the 4C-seq interactions over the background is plotted. Significant interactions (p<0.01), “targets,” are displayed in black. b, as above but for adult mouse brain (8 wks). c, as above for whole zebrafish embryos (24hrs post fertilization). In all, the region orthologous to the obesity association interval in the first intron of Fto is highlighted in pink.

Extended Data Figure 2. Long-range interactions at the FTO/IRX3 locus.

a, ENCODE data for ChIA-PET using RNA polymerase 2 (POL2) in MCF7 (human breast adenocarcinoma) cells shows interactions between IRX3 and the obesity association interval in the first intron of FTO. No interactions are observed between the FTO promoter and the association interval. This public data is available from and was visualized with the WashU EpiGenome Browser (http://epigenomegateway.wustl.edu/browser/). b, Hi-C data previously generated{Jin, 2013 #49} in human IMR-90 (fetal lung) cells. In the association interval, the IRX3 signal is stronger than the background (random) signal. However, the signal for FTO is not. c, 3C data generated with adult (8 wks) mouse brain. Using bait (red circle) in the association interval (red rectangle), we observe more frequent interactions with the Irx3 promoter compared to control regions 1 and 2 that are 29 and 42 kb away, respectively, indicative of looping.

Extended Data Figure 3. Gene expression in mouse tissue.

a, FTO expression in lung and brain, shown by RNA in situ hybridization for mouse Fto mRNA, in newborn (P1) mouse. Lungs and heart (left, whole organs) were processed simultaneously and in the same well as brain (right, sagittal section) so that the relatively higher expression in brain can be observed. b, LacZ staining for beta-galactosidase expression driven from the human FTO promoter. At top, the promoter-lacZ fusion is in the context of 162kbp of human genomic sequence carried in a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) containing the first three exons of FTO, the entire obesity-associated interval and any enhancers present. The broad expression is consistent with previous reports in human and mouse (see main text for references). At bottom, the promoter-lacZ construct is isolated: only the 1,237 bp proximal to the transcriptional start site are included. Broad expression is recapitulated, indicating the robust transcriptional competency of the human FTO promoter. c, In contrast, the 2,820 bp proximal human IRX3 promoter is not sufficient to drive lacZ expression, which is consistent with an enhancer-dependent transcriptional control mechanism.

Extended Data Figure 4. IRX3 expression in human brain.

a, IRX3 expression in human tissues including brain. Expression data, measured on Affymetrix HG-U133 arrays, were obtained from the Body Atlas, Tissues, at http://www.nextbio.com. The median expression across all 128 human tissues from 1,068 arrays is shown by the red line. b, IRX3 expression in 11 different regions of human brain. Data were retrieved from Human Brain Transcriptome data at http://www.molecularbrain.org. Abbreviations: Amyg: amygdala; Caud nuc: caudate nucleus; Cere: cerebellum; Corp Call: corpus callosum; DRG: dorsal root ganglion; Frnt Cort: frontal cortex; Hippo: hippocampus; Hypo: hypothalamus; Pit: pituitary; Spine: spinal cord; Thal: thalamus.

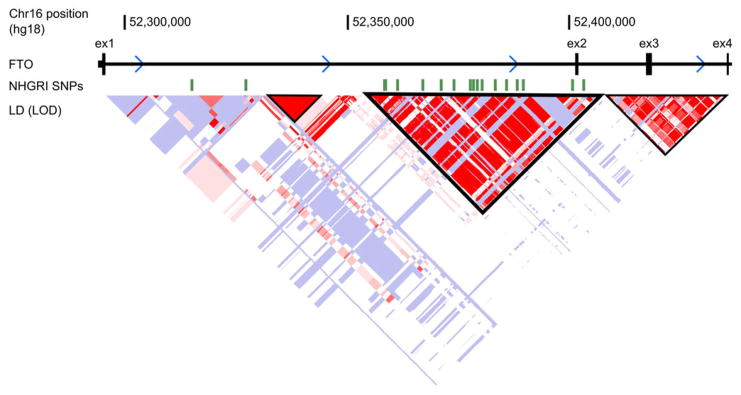

Extended Data Figure 5. Linkage Disequilibrium in FTO.

LD plot from HapMap phase II European dataset, visualized in the UCSC browser. LD blocks are outlined in black. Obesity-associated SNPs from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) GWAS catalog are shown above, in green, demonstrating why this LD block is considered to define the “association interval.

Extended Data Figure 6. Irx3KO male mice are leaner with reduced adiposity.

a, Representative photograph of WT and Irx3KO mice fed ND at 18 weeks of age. b, Representative anatomical views of WT and Irx3KO mice fed ND. Yellow dotted lines depict subcutaneous IWAT (left) and visceral PWAT (right). c, Tissue weights as a percentage of body weight showed smaller fat pad sizes in Irx3KO mice, compared to WT mice, in both ND and HFD conditions. (ND, WT/KO: n = 20/12; HFD, WT/KO: n = 8/5). Data are mean ± s.e.m. (*, P < 0.05 vs. WT, ND; #, P < 0.05 vs. WT, HFD). d, Representative H&E sections of PWAT, IWAT, and BAT from ND-fed mice demonstrated smaller adipocyte size in Irx3KO mice than control. e, qPCR of WT and Irx3KO PWAT for the indicated marker genes: Leptin (lep) and adiponectin (adipoq) are adipogenic markers, positively and negatively associated with adiposity, respectively; Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (Mcp1) correlate positively with adiposity. (*, P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding with WT value) (WT/KO: n = 10/7).

Extended Data Figure 7. Irx3KO female mice are leaner with reduced adiposity.

a, Body weight (BW) changes of WT and Irx3KO female mice fed a normal diet (ND). (WT/KO: n = 15/14). b, BMI, calculated by BW/body length2 (BL), is lower in Irx3KO female mice. (WT/KO: n = 7/7). c–d, body composition analysis showed reduced fat mass and to a less extent lean mass in Irx3KO female mice compared to WT mice, leading to decreased fat mass ratio. (WT/KO: n = 9/8). e, Representative H&E-stained sections of mammary gland (MG) WAT and periovarian (PO) WAT revealed smaller adipocyte size in Irx3KO female mice, compared to WT. f, MGWAT and BAT weights as a percentage of body weight. (WT/KO: n = 4/5). Data are mean ± s.e.m. (*, P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding with WT value)

Extended Data Figure 8. Higher energy expenditure of Irx3KO mice.

a, Energy expenditure, corrected for lean mass (kcal/kg/hr), over 24 hour period of 18 week old WT and Irx3KO mice fed with ND and HFD. (ND WT/KO: n = 7/5; HFD WT/KO: n = 8/4). b, Locomotor activity of WT and Irx3KO mice. c, Average amount of food intake over 24 hour period with or without normalization to lean mass. d, Average locomotor activity measured over 24 hours. e–f, Elevated Ucp1 gene and protein expression in BAT. (WT/KO: n = 7/6). Data are mean ± s.e.m. *, P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding with WT value.

Extended Data Figure 9. Hypothalamic-specific Irx3 dominant negative mice are leaner with reduced adiposity.

a, Schematic diagram of generation of transgenic mice overexpressing dominant-negative Irx3 in the hypothalamus. b, Immunoblotting showed EnR-Irx3 expression in the hypothalamus of mutant mice without affecting endogenous Irx3 expression, compared to control mice. c, Tissue weights as a percentage of body weight showed that fat pad sizes are smaller in mutant mice, compared to control mice. d, Reduced leptin expression and increased adiponectin gene expression in PWAT of mutant mice. (control/mutant: n = 5/7). Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. *, P < 0.05 compared to control group.

Extended Data Figure 10. Higher energy expenditure of Hypothalamic dominant negative Irx3 mice.

a, Energy expenditure, corrected for lean mass (kcal/kg/hr), over 24 hour period of 18 week old mice. b, Locomotor activity. c–d, Average amount of food intake over 24 hour period with or without normalization to lean mass. e, Average locomotor activity measured over 24 hours. f–g, Elevated gene and protein expression of Ucp1 in BAT of mutant mice. (control/mutant: n = 5/7). Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. *, P < 0.05 compared to control group.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fred Gage, Carol Marchetto, Bing Ren, Fulai Jin for their generosity in sharing reagents and data. This work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK093972, HL119967, HL114010, DK020595) to M.A.N. and (MH101820, MH090937, and DK20595) to N.J.C.. L.G.S. was funded by grants from the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (BFU2010-14839, CSD2007-00008) and the Andalusian Government (CVI-3488). C-C.H. was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research. K.-H.K. is supported by a fellowship from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. S.S. is supported by an NIH postdoctoral training grant (T32HL007381)

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

M.A.N., J.L.G.S. and C.-C.H. designed the project. J.J.T. and C.G.-M performed 4C-seq experiments, with analysis also aided by S.S. and N.J.S.. N.J.S. performed the locus conservation and regulatory block analysis. I.A., F.C., D.S., N.F.W. and S.S. performed in vivo enhancer experiments. S.S. and M.S. performed in situ hybridizations and mouse knockout phenotype calculation. E.R.G and N.J.C. performed eQTL analyses. K.-H.K performed mouse metabolic experiments. J.H.L. and D.T. contributed to histological analysis and glucose homeostasis analysis. V.P. contributed to gene and protein expression analysis. J.E.S. contributed to metabolic cage analysis. H.K.S., D.S., M.M., S.N., R.D.A., and A.N. provided scientific discussion and technical support. S.S, C.C.H, J.L.G.S, and M.A.N. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Referenes

- 1.Dina C, et al. Variation in FTO contributes to childhood obesity and severe adult obesity. Nat Genet. 2007;39(6):724–6. doi: 10.1038/ng2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frayling TM, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316(5826):889–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scuteri A, et al. Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(7):e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Church C, et al. Overexpression of Fto leads to increased food intake and results in obesity. Nat Genet. 2010;42(12):1086–92. doi: 10.1038/ng.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer J, et al. Inactivation of the Fto gene protects from obesity. Nature. 2009;458(7240):894–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao X, et al. The fat mass and obesity associated gene FTO functions in the brain to regulate postnatal growth in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e14005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunnet LG, et al. Regulation and function of FTO mRNA expression in human skeletal muscle and subcutaneous adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2009;58(10):2402–8. doi: 10.2337/db09-0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kloting N, et al. Inverse relationship between obesity and FTO gene expression in visceral adipose tissue in humans. Diabetologia. 2008;51(4):641–7. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahlen K, Sjolin E, Hoffstedt J. The common rs9939609 gene variant of the fat mass- and obesity-associated gene FTO is related to fat cell lipolysis. J Lipid Res. 2008;49(3):607–11. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700448-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMurray F, et al. Adult onset global loss of the fto gene alters body composition and metabolism in the mouse. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(1):e1003166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin F, et al. Nature. 2013;503(7475):290. doi: 10.1038/nature12644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houweling AC, et al. Gene and cluster-specific expression of the Iroquois family members during mouse development. Mech Dev. 2001;107(1–2):169–74. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Tuyl M, et al. Iroquois genes influence proximo-distal morphogenesis during rat lung development. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290(4):L777–L789. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00293.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerken T, et al. The obesity-associated FTO gene encodes a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent nucleic acid demethylase. Science. 2007;318(5855):1469–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1151710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qi L, et al. Fat mass-and obesity-associated (FTO) gene variant is associated with obesity: longitudinal analyses in two cohort studies and functional test. Diabetes. 2008;57(11):3145–51. doi: 10.2337/db08-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stratigopoulos G, et al. Regulation of Fto/Ftm gene expression in mice and humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294(4):R1185–96. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00839.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ragvin A, et al. Long-range gene regulation links genomic type 2 diabetes and obesity risk regions to HHEX, SOX4, and IRX3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(2):775–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911591107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Visel A, et al. VISTA Enhancer Browser--a database of tissue-specific human enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D88–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bosse A, et al. Identification of the vertebrate Iroquois homeobox gene family with overlapping expression during early development of the nervous system. Mech Dev. 1997;69(1–2):169–81. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixon JR, et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature. 2012;485(7398):376–80. doi: 10.1038/nature11082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gamazon ER, et al. Enrichment of cis-regulatory gene expression SNPs and methylation quantitative trait loci among bipolar disorder susceptibility variants. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;18(3):340–6. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Speliotes EK, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet. 2010;42(11):937–48. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong D, et al. GABAergic RIP-Cre neurons in the arcuate nucleus selectively regulate energy expenditure. Cell. 2012;151(3):645–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi YC, et al. Arcuate NPY controls sympathetic output and BAT function via a relay of tyrosine hydroxylase neurons in the PVN. Cell Metab. 2013;17(2):236–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mori H, et al. Critical role for hypothalamic mTOR activity in energy balance. Cell Metab. 2009;9(4):362–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dankel SN, et al. Switch from stress response to homeobox transcription factors in adipose tissue after profound fat loss. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hagege H, Klous P, Braem C, et al. Nature protocols. 2007;2 (7):1722. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N J. 2000;132:365. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, et al. Science. 2002;295 (5558):1306. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noordermeer D, Leleu M, Splinter E, et al. Science. 2011;334 (6053):222. doi: 10.1126/science.1207194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Splinter E, de Wit E, van de Werken HJ, et al. Methods. 2012;58 (3):221. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stadhouders R, Kolovos P, Brouwer R, et al. Nature protocols. 2013;8 (3):509. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denholtz M, Bonora G, Chronis C, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13 (5):602. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin F, Li Y, Dixon JR, et al. Nature. 2013;503 (7475):290. doi: 10.1038/nature12644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lieberman-Aiden E, van Berkum NL, Williams L, et al. Science. 2009;326 (5950):289. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, et al. Genome Res. 2002;12 (6):996. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, et al. Genome Res. 2009;19 (9):1639. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.ENCODE. PLoS Biol. 2011;9 (4):e1001046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou X, Wang T. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2012;Chapter 10(Unit10):10. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1010s40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li G, Ruan X, Auerbach RK, et al. Cell. 2012;148 (1–2):84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siepel A, Bejerano G, Pedersen JS, et al. Genome Res. 2005;15 (8):1034. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smemo S, Campos LC, Moskowitz IP, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21 (14):3255. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkinson DG, Nieto MA. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:361. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25025-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gamazon ER, Badner JA, Cheng L, et al. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18 (3):340. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elbein SC, Gamazon ER, Das SK, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91 (3):466. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, et al. Nat Genet. 2010;42 (11):937. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang SS, Kim KH, Rosen A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108 (33):13576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106911108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kong D, Tong Q, Ye C, et al. Cell. 2012;151(3):645. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mori H, Inoki K, Munzberg H, et al. Cell Metab. 2009;9 (4):362. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, et al. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li ZJ, Nieuwenhuis E, Nien W, et al. Development. 2012;139 (22):4152. doi: 10.1242/dev.081190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eppig JT, Blake JA, Bult CJ, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D881. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith CL, Eppig JT. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2009;1 (3):390. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith RN, Aleksic J, Butano D, et al. Bioinformatics. 2012;28 (23):3163. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dimitrieva S, Bucher P. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.