Abstract

Background

Recent experience with pandemic influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 highlighted the importance of global surveillance for severe respiratory disease to support pandemic preparedness and seasonal influenza control. Improved surveillance in the southern hemisphere is needed to provide critical data on influenza epidemiology, disease burden, circulating strains and effectiveness of influenza prevention and control measures. Hospital-based surveillance for severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) cases was established in New Zealand on 30 April 2012. The aims were to measure incidence, prevalence, risk factors, clinical spectrum and outcomes for SARI and associated influenza and other respiratory pathogen cases as well as to understand influenza contribution to patients not meeting SARI case definition.

Methods/Design

All inpatients with suspected respiratory infections who were admitted overnight to the study hospitals were screened daily. If a patient met the World Health Organization’s SARI case definition, a respiratory specimen was tested for influenza and other respiratory pathogens. A case report form captured demographics, history of presenting illness, co-morbidities, disease course and outcome and risk factors. These data were supplemented from electronic clinical records and other linked data sources.

Discussion

Hospital-based SARI surveillance has been implemented and is fully functioning in New Zealand. Active, prospective, continuous, hospital-based SARI surveillance is useful in supporting pandemic preparedness for emerging influenza A(H7N9) virus infections and seasonal influenza prevention and control.

Introduction

The 2009 influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic highlighted the need for disease surveillance to monitor severe respiratory disease to support pandemic preparedness as well as seasonal influenza prevention and control.1,2 Information generated from this type of surveillance enhances our understanding of how epidemiology and etiology differ between countries and regions of the world. The accumulated data collected in a standard and consistent way will allow rapid assessment for each influenza season and future pandemics within and among countries.2

The 2009 pandemic and seasonal influenza epidemics demonstrated the importance of having an established real-time respiratory disease surveillance system in the southern hemisphere to inform the northern hemisphere countries about newly emerging pandemic or seasonal influenza.3,4 A surveillance system can provide critical data on the epidemiology, burden, impact, circulating influenza, other respiratory pathogens and effectiveness of influenza prevention and control measures at a time when similar data in the northern hemisphere are not available.

New Zealand is an excellent location for population-based research with its predominantly public funded health-care system. All New Zealanders are assigned a unique identifier allowing tracking of health-care utilization over time and linkage to multiple databases. Primary-care providers have highly computerized information systems and patient records with detailed demographic, risk factor and immunization information. The New Zealand population is extremely well characterized regarding demographic structure, particularly by ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Indigenous Maori and Pacific peoples (collectively about 20% of the population) are particularly vulnerable to influenza and other respiratory infection-related hospitalizations.3,5

In October 2011, led by the Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR), a multicentre and multidisciplinary project – Southern Hemisphere Influenza and Vaccine Effectiveness Research and Surveillance (SHIVERS) – was established for a five-year period (2012–2016). This multiagency collaboration is between ESR, Auckland District Health Board (ADHB), Counties Manukau District Health Board (CMDHB), University of Otago, University of Auckland, WHO Collaborating Centre at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC). SHIVERS, the largest and most comprehensive influenza research initiative in the southern hemisphere, aims to: (1) understand severe acute respiratory infections; (2) assess influenza vaccine effectiveness; (3) investigate interaction between influenza and other respiratory pathogens; (4) ascertain the causes of respiratory mortality; (5) understand non-severe respiratory illness; (6) estimate influenza infection through a serosurvey; (7) determine influenza risk factors; (8) study immune responses to influenza; and (9) estimate influenza-associated health care and societal economic burden and vaccine cost–effectiveness.6

A major component of the SHIVERS project is to conduct hospital-based surveillance for severe acute respiratory infections (SARI). This report describes the implementation of this hospital-based surveillance system and provides some preliminary results from the first influenza season of its operation.

Purpose of the surveillance system

The specific aims of the hospital-based surveillance are to7:

establish active, prospective, continuous, population-based surveillance for hospitalized SARI cases, including intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and in-hospital deaths;

understand influenza’s contribution to those assessed patients not meeting the SARI case definition;

measure incidence, prevalence, demographics, clinical spectrum and outcomes for SARI and associated influenza cases;

identify etiologies of SARI cases attributable to influenza and other respiratory pathogens;

compare surveillance data with the data generated from New Zealand’s hospital discharge coding system; and

describe any possible increased risk of influenza-related hospitalization.

Implementation of the surveillance system

Population under surveillance

All residents from ADHB (central Auckland) and CMDHB (east and south Aukland) were under surveillance. Cases were reported from Auckland City Hospital and the associated Starship Children’s Hospital and Middlemore Hospital and the associated Kidz First Children’s Hospital. These four hospitals serve all residents of ADHB and CMDHB, have emergency departments and inpatient general and speciality medical services and provide all inpatient care for acute respiratory illness. The age, ethnicity and socioeconomic distribution of the urban population of 838 000 under surveillance were broadly similar to the New Zealand population (Table 1).

Table 1. Population distribution by age, ethnicity and socioeconomic group in New Zealand and surveillance population.

| Characteristics |

Percentage of total (%) | Ratio† |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

New Zealand* |

Study area* |

||

| Age group (years) | |||

| < 1 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.1 |

| 1–4 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 1.1 |

| 5–19 | 22.2 | 22.7 | 1.0 |

| 20–34 | 19.6 | 23.3 | 1.2 |

| 35–49 | 22.6 | 22.8 | 1.0 |

| 50–64 | 16.5 | 14.6 | 0.9 |

| 65 & above | 12.3 | 9.2 | 0.7 |

| Ethnic group | |||

| Asian | 8.5 | 19.2 | 2.3 |

| European | 66.9 | 46.9 | 0.7 |

| Maori | 14.0 | 11.6 | 0.8 |

| Pacific peoples | 5.6 | 15.3 | 2.7 |

| Other | 0.8 | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| Unknown | 4.2 | 5.5 | 1.3 |

| NZDep2006‡ | |||

| 1 | 10.3 | 9.6 | 0.9 |

| 2 | 10.2 | 10.1 | 1.0 |

| 3 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 1.0 |

| 4 | 10.0 | 8.6 | 0.9 |

| 5 | 9.9 | 8.2 | 0.8 |

| 6 | 9.9 | 7.9 | 0.8 |

| 7 | 9.9 | 8.3 | 0.8 |

| 8 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 1.0 |

| 9 | 10.0 | 11.3 | 1.1 |

| 10 | 9.8 | 16.2 | 1.6 |

| Unknown | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Total (n) |

100.0 (4 027 929) |

100.0 (837 696) |

|

* New Zealand population census 2006

† Ratio – percentage study area over percentage New Zealand

‡ NZDep 2006 Index of Deprivation is an area-based, census-derived measure of socioeconomic status which divides the population into deciles, where 10 represents areas with the most deprived population and 1 is the least deprived.

Note: Some columns may not add up to 100% due to the rounding off of decimal places.

Case definition

Cases included in the surveillance were overnight inpatients with suspected respiratory infections. An overnight admission is defined as: “A patient who is admitted under a medical team, and to a hospital ward or assessment unit.”7 These cases were further identified as those meeting the SARI case definition and those not meeting the SARI case definition (non-SARI). All SARI cases and a subset of non-SARI cases were enrolled.

The WHO SARI case definition was used for all age groups2:

An acute respiratory illness with:

a history of fever or measured fever of 38 °C, AND

cough, AND

onset within the past 10* days, AND

requiring inpatient hospitalization.

Expected number of cases

The discharge data for hospitalized patients in ADHB and CMDHB during the period 2006–2010 showed that the average annual number of overnight respiratory disease admissions (ICD-10 J00–99) was 9431 and influenza and pneumonia and acute lower respiratory tract infections (ICD-10 J09–22) was 5033 (Table 2). Thirty-six per cent of these admissions occurred for children under 15 years. Based on an average annual increase in respiratory disease admissions of 2.6% from 2006 to 2010, it was expected that the number of respiratory disease hospitalizations would increase by ~10% in 2012. Therefore, it was estimated that in 2012, 10 374 patients (ICD-10 J00–99) and 5537 patients (ICD-10 J09–22) would be admitted overnight with respiratory diseases.

Table 2. Overnight hospital admissions for respiratory infections and related conditions (principal diagnosis in the J00–99 range*) in Auckland District Health Board and Counties Manukau District Health Board during 2006–2010.

| Conditions | IC10 codes | Average per year | Average per week (summer) | Average per week (winter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute upper respiratory infections | J00–06 | 873 | 14 | 22 |

| Influenza and pneumonia | J09–18 | 2790 | 38 | 84 |

| Acute bronchitis | J20 | 91 | 1 | 3 |

| Acute bronchiolitis | J21 | 1246 | 15 | 42 |

| Unspecified acute lower respiratory tract infection | J22 | 906 | 13 | 26 |

| Chronic bronchitis and emphysema | J40–43 | 155 | 2 | 4 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | J44 | 1560 | 25 | 39 |

| Asthma | J45–46 | 1430 | 25 | 32 |

| Bronchiectasis | J47 | 301 | 5 | 7 |

| Respiratory failure | J96 | 79 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 9431 | 140 | 261 |

* The following respiratory conditions (roughly 1352 cases per year) were excluded because most of them are not likely to be classed as acute respiratory infections: J30–39, J60–70, J80–84, J90–94, J95, J97–99.

Summer – December to March; Winter – June to September.

While it was difficult to accurately predict the expected number of annual SARI cases based on discharge data, an early study in the Starship Children’s hospital indicated that approximately 50% of the preschool-aged children with a discharge diagnosis of pneumonia or bronchopneumonia met the WHO case definition for pneumonia.8 The ADHB laboratory data during 2010–2011 showed that 15.2% (175/1145) of respiratory specimens were positive for influenza virus.9

An average of 5500–10 000 annual cases of hospitalized respiratory diseases with 50% meeting the WHO SARI case definition would result in ~2800–5000 hospitalized SARI cases. Based on the ~10% positive detection rate, about 280–500 laboratory-confirmed influenza cases would be expected among these hospitalized SARI patients.

Case ascertainment and data collection

Case ascertainment followed a surveillance algorithm. The presence of the components of the case definition was determined by reviewing clinicians’ admission diagnoses and interviewing patients. Records of all acutely admitted patients were reviewed daily to identify any overnight inpatient with a suspected respiratory infection. These patients were categorized into one of 10 admission diagnostic syndrome groups. Research nurses interviewed these patients, documented the components of the case definition that were present and differentiated patients into SARI and non-SARI cases.

A case report form for each assessed patient captured patient demographics, presenting symptoms and illness, pre-hospital health care, medication usage, influenza vaccination history, co-morbidities, disease course and outcomes, epidemiological risk factors and laboratory results.

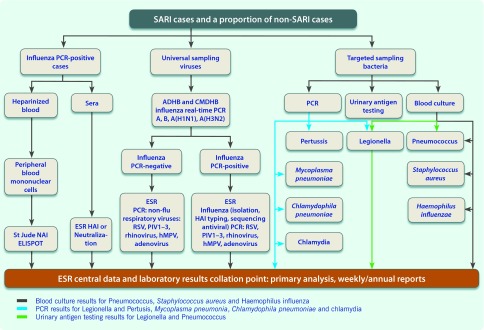

Clinical specimens were taken from all SARI and some non-SARI patients (for clinical management purposes) (Fig. 1). The preferred respiratory specimens for adult and paediatric patients were nasopharyngeal swabs and nasopharyngeal aspirates, respectively. Where possible, at least one lower respiratory tract sample (tracheal aspirate, bronchial wash or bronchoalveolar lavage) was collected from all ventilated patients.

Fig. 1.

Specimen collection and testing for SARI cases and a proportion of non-SARI cases

ADHB – Auckland District Health Board; CMDHB – Counties Manukau District Health Board; ELISPOT – enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot; ESR – Institute of Environmental Science and Research; HAI – haemagglutination inhibition assay; hMPV – human metapnemovirus; NAI – neuraminidase inhibition assay; PIV1–3 – parainfluenza virus types 1–3; PCR – polymerase chain reaction; RSV – respiratory syncytial virus.

Laboratory component

Influenza and other non-influenza respiratory viruses

The ADHB laboratory and ESR used US-CDC’s real-time RT–PCR protocol for influenza virus.10 CMDHB laboratory used the Easy-Plex PCR assay for influenza virus (AusDiagnostic Pty Ltd, New South Wales, Australia).11 Comparison between AusDiagnostic with US CDC’s assays showed that AusDiagnostic assay had a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 96.6% when US CDC method was used as a gold standard.

All SHIVERS samples were forwarded to ESR for further characterization/storage. The WHO standard manual was used to conduct antigenic, genetic and antiviral characterization.12 Any unsubtypeable influenza A viruses were forwarded to WHO collaborating centres in Melbourne or Atlanta.

US CDC’s real-time RT–PCR for non-influenza respiratory viruses was performed for respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus 1–3, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus and adenovirus.13,14

Respiratory bacteria

Sampling and testing for respiratory bacteria was based on the hospital clinical management and diagnostic protocols.

Urinary antigen tests (a rapid immuno-chromatographic test) from Binax (Auckland, New Zealand) were used for all strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1.

The ADHB laboratory used blood culture media, BD Bactec-plus aerobic/F and Bactec Lytic/10 anaerobic/F from Becton, Dickinson and Co. (Auckland, New Zealand). The CMDHB laboratory used BacT/ALERT-FA-Plus, FN-Plus and PF-Plus bottles from BioMérieux (Auckland, New Zealand).

The CMDHB laboratory used AusDiagnostic PCR assay (Bordetella and atypical pneumonia, Cat. 3078) to detect: pan-Legionella; Legionella longbeachae, Legionella pneumophila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, pan-Chlamydia, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis and Pneumocystis jiroveci.

Data analysis and dissemination

The total number of all hospital acute admissions and assessed and tested patients, including ICU admissions and deaths and census data, were collected. This allowed calculation for population-based incidence for SARI and associated influenza cases by overall and stratified population (age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic status) for the ADHB and CMDHB population (2006 census data). This also allowed calculation for proportion of SARI and associated influenza cases, including ICU admissions and deaths, by overall and stratified patients among all acute admissions. An acute admission is an unplanned admission on the day of presentation at the admitting health-care facility. Admission may have been from the emergency or outpatient departments of the health-care facility, a transfer from another facility or a referral from primary care.

Weekly reports during May–September and monthly reports during October–April were produced.

Annual reports described epidemiologic, clinical, virologic/microbiologic characteristics, risk factor analysis of SARI and associated influenza and other respiratory pathogen cases, and antigenic, genetic and antiviral characterization of influenza viruses.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the Northern A Health and Disability Ethics Committee (NTX/11/11/102 AM02). Written consent is not necessary for non-sensitive data from routine in-hospital clinical management and diagnostic testing. Verbal explanation of the reason for additional information and its use was given to each patient, consistent with the New Zealand Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights (Right 6: Right to be fully informed).15

Preliminary results

From 30 April to 30 September 2012 there were 59 124 acute admissions to ADHB and CMDHB hospitals. A total of 4417 (7.5%) patients with suspected respiratory infections were assessed. Of these, 2023 (45.8%) met the SARI case definition. Of the 1430 SARI cases from whom nasopharyngeal specimens were collected, 324 (22.7%) had influenza viruses. A small proportion of influenza-positive cases (7.1%, 21/294) were identified from patients with onset in the past seven to 10 days, so the case definition was expanded to onset within the past 10 days for subsequent study years (2013–2016). A small proportion (8.8%, 37/419) of influenza-positive cases was from non-SARI cases tested for clinical purposes.

Discussion

Value of SARI surveillance

Hospital-based SARI surveillance has been implemented and fully functioning in New Zealand since 30 April 2012. WHO is encouraging Member States to establish SARI surveillance that meets WHO global standards.2 To our knowledge, New Zealand is among the first developed countries to do this, providing better understanding of the epidemiology, transmission and impact of influenza locally and globally.

New Zealand’s existing hospital-based disease surveillance is well suited to strategic surveillance functions.16 However, such systems are not suited to control-focused surveillance where it is necessary to identify and respond in a timely manner to individual events.16 Thus, the active, prospective, continuous, hospital-based SARI surveillance provided by the SHIVERS project is particularly useful in supporting both pandemic preparedness for emerging influenza A(H7N9) virus and seasonal influenza prevention and control. SARI surveillance has been a valuable platform for the study of other common respiratory pathogens and preparing for emerging respiratory viral diseases such as novel coronavirus, MERS-CoV.

Limitations and potential improvements to SARI surveillance

The WHO SARI case definition, based on clinical symptoms and signs, will miss some illnesses caused by influenza infection and include some illnesses caused by non-influenza infections.2,17 The SHIVERS SARI surveillance system provides a comprehensive and thorough algorithm for case ascertainment and testing for all SARI and some non-SARI cases. It offers a unique opportunity to define cases of influenza not captured currently from patients who do not meet WHO SARI case definition, thus enabling further refinement of the WHO case definition. Additionally, the SHIVERS SARI surveillance system offers an opportunity to evaluate sensitivity and specificity of the WHO SARI case definition and predicting symptoms for capturing non-influenza respiratory viruses.

SARI surveillance is limited in identifying influenza virus-infected patients with atypical clinical presentations (respiratory and non-respiratory). Influenza infection can lead to more severe illness and complications such as primary viral pneumonia, secondary bacterial pneumonia, cardiac complications and neurological complications. Influenza infection can also cause exacerbations of underlying diseases such as chronic lung disease or cardiovascular disease. Some of the complications and exacerbations may occur after typical influenza-related clinical symptoms have resolved, and influenza infection may not be suspected as a cause in these complications.

SARI surveillance can characterize socio-demographic risk factors (age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic deprivation) as the distribution of these characteristics is well defined in census data in New Zealand. For other more specific risk factors, there are limited data available on their distribution in the population. As SARI surveillance is a case-finding surveillance for hospitalized inpatients, it is limited to quantify the impact of these specific risk factors for SARI-related influenza infections without their baseline distributions. Consequently, it is necessary to identify a suitable comparison/control population. During 2013, a hospital-based control population without respiratory illness will be added to investigate specific risk factors for influenza and other respiratory diseases.

The case report form captures information by interviewing patients/caregivers through their recall, which generates bias. An important example is influenza vaccination status, which is crucial for estimating vaccine effectiveness. The Ministry of Health in New Zealand plans to add influenza vaccination to its national immunization register in 2014, providing more accurate vaccination history for SARI cases than patient/caregiver recall.

Acknowledgements

The SHIVERS project is a multicentre and multidisciplinary collaboration. Special thanks to these collaborating organizations for their commitment and support: ESR, ADHB, CMDHB, University of Otago, University of Auckland, US CDC and WHO Collaborating Centre at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, USA. Special thanks to: the research nurses at ADHB; the research nurses at CMDHB; staff of the WHO National Influenza Centre, ESR; the Health Intelligence Team, ESR; staff of the ADHB laboratory and CMDHB laboratory; IT staff and SARI surveillance participants. Also, a special thanks to Dr Dean Erdman from Gastroenteritis and Respiratory Viruses Laboratory Branch, US CDC, who provided the real-time PCR assay for non-influenza respiratory viruses. Support in kind was provided by the Ministry of Health.

All authors participated in designing and establishing SARI surveillance and revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Conflicts of interests

None declared.

Funding

The SHIVERS project is funded by US CDC (1U01IP000480-01). The hospital-based surveillance is a key component of the SHIVERS project. The project is a five-year research cooperative agreement between ESR and US CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases Influenza Division.

Note: onset within the past seven days was used in the 2012 study protocol.

References

- 1.Ortiz JR, et al. Strategy to enhance influenza surveillance worldwide. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2009;15:1271–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.081422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Global Epidemiological Surveillance Standards for Influenza. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. http://www.who.int/influenza/resources/documents/influenza_surveillance_manual/en/index.html accessed 5 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker MG, et al. Pandemic influenza A(H1N1)v in New Zealand: the experience from April to August 2009. Eurosurveillance: European Communicable Disease Bulletin. 2009;14(34):pii:19319. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.34.19319-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang QS, et al. Influenza surveillance and immunisation in New Zealand, 1997–2006. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 2008;2:139–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2008.00050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker MG, et al. Increasing incidence of serious infectious diseases and inequalities in New Zealand: a national epidemiological study. Lancet. 2012;379:1112–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61780-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The SHIVERS Project - Study overview. New Zealand: Institute of Environmental Science and Research; 2011. http://www.esr.cri.nz/competencies/shivers/Pages/StudyOverview.aspx accessed 5 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez L, Wood T, Huang QS. Influenza surveillance in New Zealand, 2012 and 2013. https://surv.esr.cri.nz/virology/influenza_annual_report.php accessed 6 May 2014.

- 8.Grant CC, et al. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in pre-school-aged children. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2012;48:402–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson DA, et al. Surveillance for influenza using hospital discharge data may underestimate the burden of influenza-related hospitalization. Infection control and hospital epidemiology: the official journal of the Society of Hospital Epidemiologists of America. 2012;33(10):1064–1066. doi: 10.1086/667742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shu B, et al. Design and performance of the CDC real-time reverse transcriptase PCR swine flu panel for detection of 2009 A (H1N1) pandemic influenza virus. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2011;49:2614–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02636-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szewczuk E, et al. Rapid semi-automated quantitative multiplex tandem PCR (MT-PCR) assays for the differential diagnosis of influenza-like illness. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2010;10:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Global Influenza Surveillance Network. Manual for the laboratory diagnosis and virological surveillance of influenza. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. 153 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heim A, et al. Rapid and quantitative detection of human adenovirus DNA by real-time PCR. Journal of Medical Virology. 2003;70:228–39. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu X, et al. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for comprehensive detection of human rhinoviruses. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2008;46:533–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01739-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights. Auckland: Health and Disability Commissioner; 2009. http://www.hdc.org.nz/the-act — code/the-code-of-rights accessed 5 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker MG, Easther S, Wilson N. A surveillance sector review applied to infectious diseases at a country level. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:332. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray EL, et al. What are the most sensitive and specific sign and symptom combinations for influenza in patients hospitalized with acute respiratory illness? Results from western Kenya, January 2007-July 2010. Epidemiology and Infection. 2013;141:212–22. doi: 10.1017/S095026881200043X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]