Since late 2013 through March 2014, Japan experienced a rapid rise in measles cases. Here, we briefly report on the ongoing situation and share preliminarily findings, concerns and challenges and the public health actions needed over the coming months and years.

Measles is a notifiable disease in Japan based on nationwide case-based surveillance legally requiring physicians to report all clinically diagnosed and laboratory-confirmed cases within seven days, but preferably within 24 hours. After a large outbreak in 2007–2008 (more than 11 000 cases reported in 2008 alone) and a goal of elimination by April 2015, a catch-up programme using the bivalent measles-rubella (MR) vaccine was offered for grades seven and 12 (ages 12–13 and 17–18 years) from April 2008 through March 2013. During this period, there was an estimated 97% decline in measles notifications, and the cumulative number of reported cases has been steadily declining over the last five years (732 cases in 2009, 447 cases in 2010, 439 cases in 2011, 293 cases in 2012 and 232 cases in 2013). However, since late 2013 through March 2014, the country experienced a resurgence only a year after a large rubella outbreak.1,2 During epidemiologic week 48 of 2013 to week 10 of 2014, as of 13 March 2014, 183 measles cases were reported (141 laboratory-confirmed, 26 clinically diagnosed and 16 laboratory-confirmed modified measles cases); 92 of the cases were male (50%) with a median age of 12 years (range four months to 52 years). Cases have been reported throughout Japan.3 While no deaths from measles were reported, a case of encephalitis associated with measles infection occurred.3 With 171 cases reported during weeks 1–10 of 2014 (relative to 158 cases in 2009, 89 cases in 2010, 73 cases in 2011, 74 cases in 2012 and 52 cases in 2013 for weeks 1–10 for each respective year) there is concern that the declining trend will likely be reversed this year.

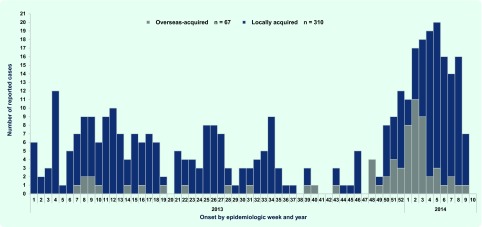

Among the 183 cases, 52 (28%) had recent overseas travel histories within three weeks before onset with the majority coming from the Philippines (n = 41), where measles cases began increasing in October–November 2013.4 Among the 105 cases that were genotyped since week 48 of 2013, the majority were B3 (n = 99), a genotype that had not been detected in Japan until 20134,5 and the sole genotype detected in the Philippines in 2013 (n = 33).4 Among the 41 cases with recent travel history to the Philippines, 39 were B3, one D9 and another unknown. Based on the available epidemiologic and genetic information, the recent increase since late November 2013 appears to be linked to the Philippines.4,6,7 Other countries have also reported genotype B3 measles cases in travellers returning from the Philippines since late 2013, including Australia, Canada, Italy, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.8–10 Importantly, while transmission occurred locally in 128 of the cases (70%) during week 48 of 2013 to week 10 of 2014, the change in the proportion and rate of imported cases over time has reflected the evolving epidemiologic situation in Japan. Prior to the increase in notification rates, the proportion of cases believed to have been infected overseas was low at 7% (15/204) during weeks 1–47 of 2013, then rose to 52% (42/81) during week 48 of 2013 to week three of 2014 and then declined to 11% (10/92) during weeks 1–10 of 2014. While the notification rate of overseas-acquired cases rose and then declined during these respective periods, the rate for locally acquired cases continued to rise. Thus, while the recent increase began with overseas-acquired cases, the majority of the latest cases, also genotype B3, likely emerged as ongoing, locally acquired transmissions (Figure 1). In addition to family clusters, at least 22 cases were believed to have been infected nosocomially, and school-associated transmissions also emerged. Similarly, further transmissions from overseas-acquired cases associated with travel to the Philippines have been reported from the United Kingdom,8 the United States,9,11 and in the Mediterranean.10

Figure 1.

Number of reported measles cases by onset by epidemiologic week, Japan, January 2013 to March 2014

Notably, among the 183 cases, 146 (80%) had either no or unknown history of measles vaccination. While nearly a quarter of the affected were aged one year or below (those not yet ready for vaccination and with waning maternal immunity), the large number of unvaccinated older paediatric and young adult cases are believed to have contributed to the ongoing transmission. Our preliminary findings point towards both the relative overall effectiveness of measles vaccination and that pockets of unvaccinated/susceptible populations remain, sustaining transmission following importation.

While there are limitations in the reported surveillance data, including potential underreporting and misdiagnosis, such missing or misclassified cases are unlikely to be differentially associated with importation status or with temporality and thus unlikely to alter our qualitative interpretation. Although clinicians may have tended to suspect measles for those with overseas travel, the fact that the recent increase was mostly due to cases without such travel supports the notion of a true increase due to ongoing locally acquired transmissions.

The measles situation in Japan warrants both timely and sustained public health response. Continued vigilance for imported cases is imperative, and at the same time there is a need to be alert against secondary transmission and respond rapidly to each suspected case. With Japan’s announcement in 2013 easing visa requirements for visitors from South-East Asia12 and with Tokyo’s Haneda Airport increasing international flights,13 the risk of importation will increase. Thus, sustained and routine measles vaccination, with high coverage to maintain herd immunity is essential. Travellers overseas should also ensure that they are vaccinated to prevent importation in the first place. MR vaccine is the ideal strategy to prevent infection from both viruses and prevent potentially severe outcomes such as measles encephalitis and congenital rubella syndrome. Japan’s National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and other partners are actively communicating these key messages via the Internet, television and newspapers to the general public and to the medical and public health communities.3 While vaccination rates have vastly improved since 2007–2008, there is a need to better understand those who remain under or unvaccinated.

Japan is responding to a challenging measles situation and is about to enter its historic peak season in the spring. The current situation highlights the importance of both rapid response and routine public health activities. These messages should not be lost, especially at these opportune times. We are actively communicating with our fellow public health and medical practitioners to share timely measles information and re-emphasize the importance of MR vaccination.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the staff at local public health centres and prefectural and municipal public health institutes nationwide, notifying physicians and other public health and medical staff who have been responding to the ongoing measles situation. We sincerely appreciate the rapid laboratory diagnosis and reporting by the prefectural and municipal institutes of public health that have allowed for rapid assessments and response. In addition, we acknowledge the local public health workers who continue to work with dedication not only during acute response times but also during times of peace, implementing and promoting important prevention activities.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Infectious Disease Surveillance Center. Cumulative number of rubella cases by week, 2008–2014 (week 1–10). Tokyo: Infectious Disease Surveillance Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases; 2014. http://www0.nih.go.jp/niid/idsc/idwr/diseases/rubella/rubella2014/rube14-10.pdf accessed 21 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugishita Y, et al. Ongoing rubella outbreak among adults in Tokyo, Japan, June 2012 to April 2013. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal. 2013;4:37–41. doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2013.4.2.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Infectious Disease Surveillance Center. Measles situation update, epidemiologic week 48, 2013 – epidemiologic week 8, 2014. Tokyo: Infectious Disease Surveillance Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases; 2013. http://www.nih.go.jp/niid/en/all-surveillance/2292-idwr/idwr-article-en/4440-idwrc-1408-en.html accessed 20 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Expanded Programme on Immunization. Measles-Rubella Bulletin. Manila: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2014. http://www.wpro.who.int/immunization/documents/measles_rubella_bulletin/en/index.html accessed 20 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Infectious Disease Surveillance Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases. An imported case of measles virus genotype B3 infection from Thailand, May 2013-Fukuoka City. Infectious Agents Surveillance Report. 2013;34:201–202. http://www.nih.go.jp/niid/ja/measles-m/measles-iasrd/3666-pr4012.html [in Japanese] accessed 20 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Measles situation in the Philippines – FAQs, January 2014. Manila: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2014. http://www.wpro.who.int/philippines/mediacentre/features/measles_faq/en/ accessed 19 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Epidemiology Center. Disease Surveillance Report: measles cases in the Philippines - morbidity week 7, February 9–15, 2014. Manila: National Epidemiology Center, Public Health Surveillance and Informatics Division, Department of Health; 2014. http://nec.doh.gov.ph/images/MEASLES2014/measlesmw7.pdf accessed 20 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health England. Measles cases with links to the ongoing outbreak in the Philippines. Health Protection Report. 2014;8(10):14. http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpr/archives/2014/news1014.htm#mslslnn accessed 20 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Measles in the Philippines. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2014. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/watch/measles-phillipines accessed 20 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanini S, et al. Measles outbreak on a cruise ship in the western Mediterranean, February 2014, preliminary report. Euro Surveillance: European Communicable Disease Bulletin. 2014;19(10):pii=20735. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.10.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aleccia J. Measles uptick in U.S. linked to Philippines, CDC says. NBC News. 2014 4 March http://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/measles-uptick-u-s-linked-philippines-cdc-says-n43541 accessed 18 March 2014.

- 12.Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. http://www.mofa.go.jp/j_info/visit/visa/index.html [Internet] accessed 21 March 2014.

- 13.Tokyo International Air Terminal. Start date for the expansion of the Tokyo International Air Terminal. Tokyo: Tokyo International Air Terminal; 2014. http://www.haneda-airport.jp/inter/info/N0000085/201402251600.pdf [in Japanese] accessed 21 March 2014. [Google Scholar]