Two subclades of the CLCF-type F−/H+ antiporters show differences in F−/Cl− selectivity.

Abstract

Many bacterial species protect themselves against environmental F− toxicity by exporting this anion from the cytoplasm via CLCF F−/H+ antiporters, a subclass of CLC superfamily anion transporters. Strong F− over Cl− selectivity is biologically essential for these membrane proteins because Cl− is orders of magnitude more abundant in the biosphere than F−. Sequence comparisons reveal differences between CLCFs and canonical Cl−-transporting CLCs within regions that, in the canonical CLCs, coordinate Cl− ion and govern anion transport. A phylogenetic split within the CLCF clade, manifested in sequence divergence in the vicinity of this ion-binding center, raises the possibility that these two CLCF subclades might exhibit differences in anion selectivity. Several CLCF homologues from each subclade were examined for F−/Cl− selectivity of anion transport and equilibrium binding. Differences in both of these anion-selectivity metrics correlate with sequence divergence among CLCFs. Chimeric constructs identify two residues in this region that largely account for the subclade differences in selectivity. In addition, these experiments serendipitously uncovered an unusually steep, Cl−-specific voltage dependence of transport that greatly enhances F− selectivity at low voltage.

INTRODUCTION

Aqueous F− has pervaded our environment for eons, but until recently, this anion was ignored as a physiologically relevant substrate in biological systems. However, it is now known that many unicellular microorganisms use membrane transport proteins to export F− when cytoplasmic levels approach toxic concentrations of 10–100 µM (Baker et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013). Among these are the CLCF-type F−/H+ antiporters, a subset of the ubiquitous CLC superfamily of anion channels and transporters, phylogenetically distant from the long-studied canonical CLCs involved in Cl− and NO3− physiology (Zifarelli and Pusch, 2007; Accardi and Picollo, 2010). Appearing exclusively in bacteria, CLCFs export F− to combat environmental F− toxicity. We previously noted a high selectivity of CLCFs for F− over Cl− in eight homologues examined (Stockbridge et al., 2012) and therefore presumed this feature essential for their F−-protective purposes. Because many anion channels and transporters select against F− and because F− selectivity is difficult to achieve in synthetic host–guest systems of small molecule ligands (Cametti and Rissanen, 2009), these F−-selective exporters have apparently evolved novel chemical mechanisms to satisfy their biological imperatives.

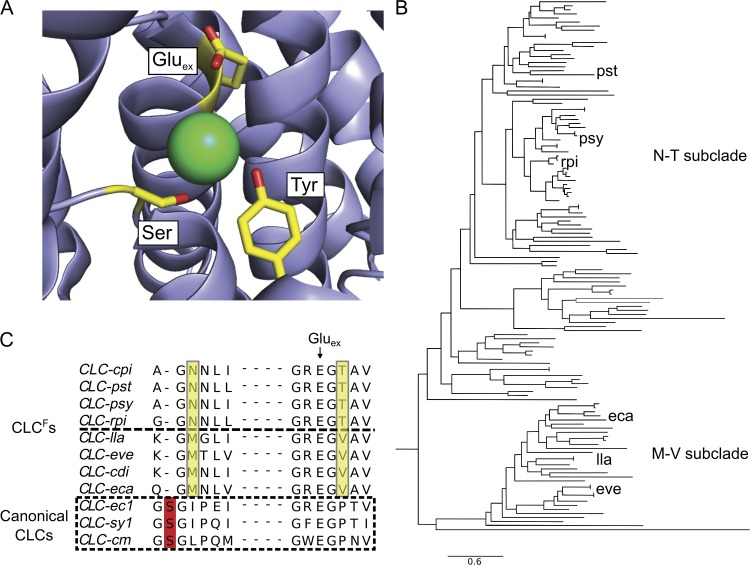

Extensive work on anion transport function and high-resolution structure of the canonical CLC Cl−/H+ antiporters (Fig. 1 A) has established that the side chain hydroxyls of highly conserved serine and tyrosine residues, as well as a critical glutamate (Gluex), form a mechanistic center of the protein by coordinating a transported Cl− ion (Dutzler et al., 2003; Accardi et al., 2006; Miller, 2006; Zifarelli and Pusch, 2007; Picollo et al., 2009). The CLCFs retain the conserved Gluex, and a CLCF tyrosine near the C terminus, despite poor alignment in this region, may serve this anion-coordinating function. However, the canonical serine that initiates helix-D is absent in CLCFs, which carry either an Asn or Met at a roughly equivalent position (Fig. 1 B). Moreover, these residues cosegregate with two phylogenetically distinct CLCF subclades (Fig. 1 C), which are also strictly marked by either a Thr or Val in helix-F near Gluex. Henceforth, these are denoted as “N-T” and “M-V” subclades. The question immediately arises as to whether these subclades display phenotypic differences that might offer a window into the unusual anion selectivity of the transporters. We find significant though rather subtle differences in F−/Cl− selectivity, which faithfully track with the two CLCF subclades. Moreover, selectivity swaps show that these differences may be mapped to these two N-or-M and T-or-V positions.

Figure 1.

Canonical and F− transporting CLCs. (A) High-resolution structure of a canonical CLC Cl−/H+ antiporter, CLC-ec1 (PDB ID: 1OTS), reveals the conserved Glu, Ser, and Tyr Cl− coordinating residues. The green sphere represents the Cl− ion. (B) Phylogenetic tree of the CLCF clade, showing N-T and M-V subclades. Homologues used in this study are indicated. (C) Sequence alignment of several CLCF homologues in the helix D and helix F regions. Yellow boxes highlight residues differing between CLCF subclades and strictly conserved within them. Sequences in same region of canonical CLCs of known structure are shown below, with red boxes denoting the Cl−-coordinating Ser residue.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and CLCF constructs

Chemicals were of the highest grade available from Sigma-Aldrich. Escherichia coli–mixed phospholipids (EPL) were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. and detergents from Anatrace. Isethionate salts were prepared from isethionic acid (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) and the appropriate base. Synthetic gene constructs of the CLCF homologues, optimized for E. coli expression (GenScript), were inserted into a pASK vector containing a C-terminal hexahistidine tag (Stockbridge et al., 2012), and site-directed mutagenesis was performed using standard PCR techniques. The six homologues used here, three from each subclade, were chosen for expression levels and biochemical stability, and are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of CLCF homologues

| Homologue nickname | Source organism | NCBI Protein reference sequence | Gram stain |

| CLC-pst | Pirellula staleyi | YP_003370005.1 | negative |

| CLC-rpi | Ralstonia pickettii | YP_001892513.1 | negative |

| CLC-psy | Pseudomonas syringae | WP_010202072.1 | negative |

| CLC-eca | Enterococcus casseliflavus | WP_005229670.1 | positive |

| CLC-lla | Lactococcus lactis | YP_001032764.1 | positive |

| CLC-eve | Eubacterium ventriosum | WP_005363921.1 | positive |

Phylogenetic calculations

CLCF homologue sequences obtained from the PFAM database were aligned using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al., 2010), and the output tree was analyzed using SeaView (Gouy et al., 2010) and FigTree software.

Protein purification and liposome reconstitution

E. coli (BL21-DE3) cells transformed with a plasmid bearing CLCF homologues were grown at 37°C in Terrific broth containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin to an OD600 ≈ 0.8 and were induced with 0.2 mg/liter anhydrotetracycline for 2–3 h at 37°C. Cells were resuspended in 50 ml of 100 mM NaCl and Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and lysed by sonication in the presence of protease inhibitors leupeptin (20 µg/ml), pepstatin (20 µg/ml), and PMSF (∼0.2 mg/ml). Membranes were extracted for 2 h with gentle shaking at room temperature in the presence of 80 mM n-decyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DM). Cell debris was pelleted, and the supernatant was passed over cobalt affinity beads (Talon, 1 ml/liter culture), which was washed with 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM DM, and 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and subsequently with the same solution supplemented with 40 mM imidazole. CLCF protein was eluted by jumping imidazole to 400 mM. Protein was concentrated and loaded onto a Superdex 200 size-exclusion column equilibrated in 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 25 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7, and 5 mM DM; all homologues were >95% pure, as judged by Coomassie staining. Proteoliposomes were formed by dialysis of a micellar mix of protein (3–5 µg protein/mg lipid), 10 mg/ml lipid, and 35 mM 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) against the desired intraliposomal solution at room temperature for 36 h. Liposomes were stored in aliquots at −80°C until use. Before functional assays, liposomes were extruded 21 times through a 400-nm membrane filter.

F− and Cl− efflux measurement

Details of the anion efflux methods used here have been reported previously (Walden et al., 2007). In brief, for F− efflux assays, liposomes were prepared with an internal solution of 300 mM KF and 25 mM HEPES, pH 7. Samples were passed through Sephadex G50 spin columns (100 µl per 1.5-ml column) equilibrated with 300 mM Na+- or K+-isethionate, 1 mM NaF, and 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, and 0.4 ml of the combined eluates was immediately diluted into a stirred vessel containing 3.6 ml of the same buffer. Transport was initiated by adding appropriate cation ionophores valinomycin (Vln) or gramicidin A (gA; 1 µg/ml), and appearance of F− in the external solution was continuously monitored with a La/EuF3 electrode (Cole-Parmer). After uptake had reached steady-state, 30 mM n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (OG) was added to release any untransported F−. Transport was calibrated with NaF standards. Cl− efflux assays were performed similarly with Cl− solutions and were monitored with Ag/AgCl electrodes.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

Thermodynamic binding parameters of F− and Cl− to CLC-pst and CLC-eca were determined with a microcalorimeter (350-µl sample volume; Nano ITC; TA Instruments) as previously described (Lim et al., 2013). CLCF protein was purified as above, except that low- or zero-halide salts were used: 100 mM Na/K tartarate, 2 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, and 400 mM imidazole-SO4, pH 7.5, for the cobalt column and 100 mM Na/K tartrate and 10 HEPES, pH 7.0, for the size-exclusion column. 150–200 µM protein was titrated with 1-µl injections of 10–60 mM F− or Cl− at 25°C, and data were fitted with single-site isotherms using NanoAnalyze 2.4.1 software. For homologues that could not tolerate low-halide solutions, protein was purified in buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, and F− titrations were performed with 50 mM Cl− present.

Light-scattering efflux assay

Efflux of F− and Cl− was in some cases monitored by 90° light scattering at 600 nm (Stockbridge et al., 2012). Proteoliposomes were prepared as above and diluted 200-fold into an isotonic external buffer containing 300 mM Na+-, K+-, or N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMG+)-isethionate and 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, in a stirred cuvette. Flux was initiated with Vln or gA. As salt leaves the liposomes, water follows to maintain osmotic balance, leading to time-dependent liposome shrinkage accompanied by an increase in light scattering (Jin et al., 1999), a signal which is linear with ion efflux under these conditions. When efflux reached steady-state, untransported ions from the liposomes were released with 1 µM tributyltin (TBT) and carbonylcyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) for Cl− efflux or 1 µM FCCP alone for F− efflux (because this proton ionophore acidifies the liposome interior, forming membrane-permeant hydrofluoric acid). To set transmembrane voltage, varying ratios of Na+/K+-isethionate in the external solution were used, with internal 300 mM K+ constant.

F− and Cl−-driven H+ pumping

Liposomes were prepared with an internal solution of 300 mM KF (or KCl) and 25 mM HEPES, pH 7. Samples were passed through Sephadex G50 spin columns (100 µl per 1.5-ml column) equilibrated with 300 mM Na+-isethionate and 1 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, and 0.2 ml of the combined eluates was immediately diluted into a stirred vessel containing 1.8 ml of the same buffer. Transport was initiated by addition of Vln, and proton uptake was monitored with a pH electrode in the external solution. Once transport reached steady-state, the proton gradient was dissipated by the addition of 1 µM FCCP, and H+ transport was calibrated with an HCl standard solution (Stockbridge et al., 2012).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows, for two CLCF homologues from each subclade, raw traces of thermodynamically uphill proton influx driven by F− or Cl− gradients. Fig. S2 supplements the data of Fig. 2 by showing raw traces of anion efflux at zero voltage. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jgp.org/cgi/content/full/jgp.201411225/DC1.

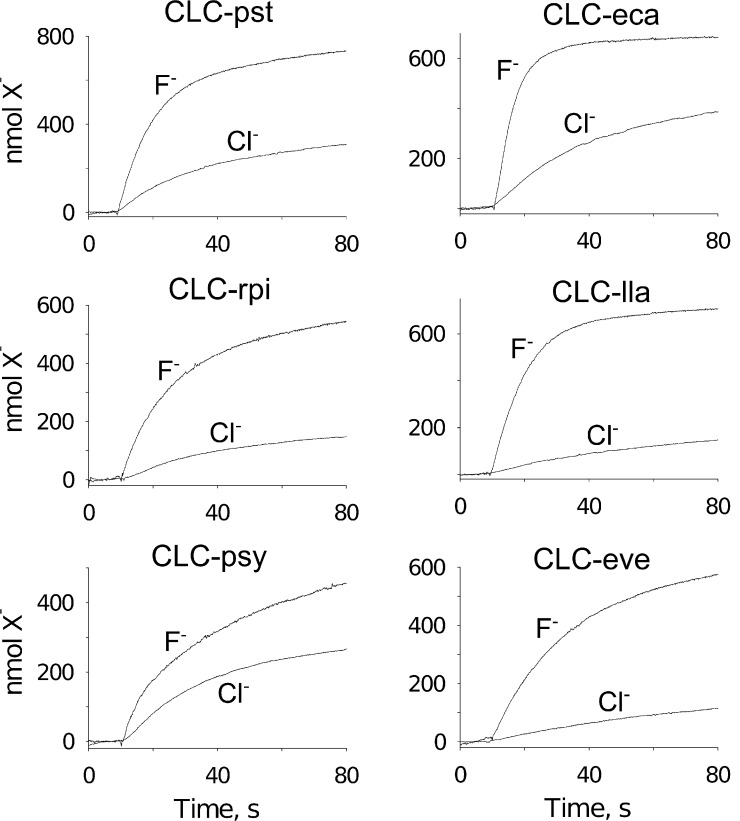

Figure 2.

Anion transport for several CLCF homologues. For each homologue of the N-T subclade (left) or the M-V subclade (right), transport was initiated after 10 s of recording a baseline, and appearance of the anion in (X−) the external solution was monitored.

RESULTS

The N-T versus M-V subclades show conserved sequence differences in regions that are known to be near equivalent Cl−-coordinating residues in canonical CLCs. We therefore wondered whether the subclades differ in selectivity for F−. Accordingly, F− and Cl− efflux were examined for three homologues representative of each subclade (Fig. 2 and Table 1). In these experiments, each CLCF homologue was purified and reconstituted into liposomes containing either 300 mM KF or 300 mM KCl. The liposomes were suspended in a solution containing 1 mM of the test ion osmotically balanced with the impermeant salt Na-isethionate. Efflux of the anion down its 300-fold gradient was initiated by addition of the K+ ionophore Vln to permit counterion movement, and the initial rate of appearance of the anion in the external solution was determined with ion-specific electrodes. Homologues were confirmed to show H+ antiport in exchange for both F− and Cl− (Fig. S1), with much less proton coupling to Cl− than the strict 1:1 stoichiometry known for F−/H+ antiport (Stockbridge et al., 2012). Absolute transport rates determined from the initial slope of the efflux time course vary greatly among the six homologues tested (Table 2), but the ratio of these rates, the F−/Cl− transport selectivity, reveals a difference between the two subclades, with the M-V subclade roughly twice as selective for F− as the N-T subclade (approximately sixfold vs. approximately threefold over Cl−).

Table 2.

F− and Cl− turnover rates for several CLCF homologues

| Subclade | Homologue | F− turnover | Cl− turnover | F−/Cl− ratio for subclade |

| s−1 | s−1 | |||

| N-T | CLC-pst | 810 ± 80 | 320 ± 20 | |

| N-T | CLC-rpi | 420 ± 30 | 130 ± 10 | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

| N-T | CLC-psy | 460 ± 40 | 230 ± 10 | |

| M-V | CLC-eca | 880 ± 40 | 280 ± 20 | |

| M-V | CLC-lla | 580 ± 30 | 90 ± 10 | 6.1 ± 0.6 |

| M-V | CLC-eve | 420 ± 40 | 50 ± 10 |

F− and Cl− turnovers were calculated (±SEM; n = 6) using three independent reconstitutions of protein at 3 µg/mg lipid, and each preparation was assayed in duplicate. Subclade ratios were calculated from the ratios of independent trials (n = 18). The difference in the F−/Cl− ratio between the subclades is statistically significant (P < 0.001).

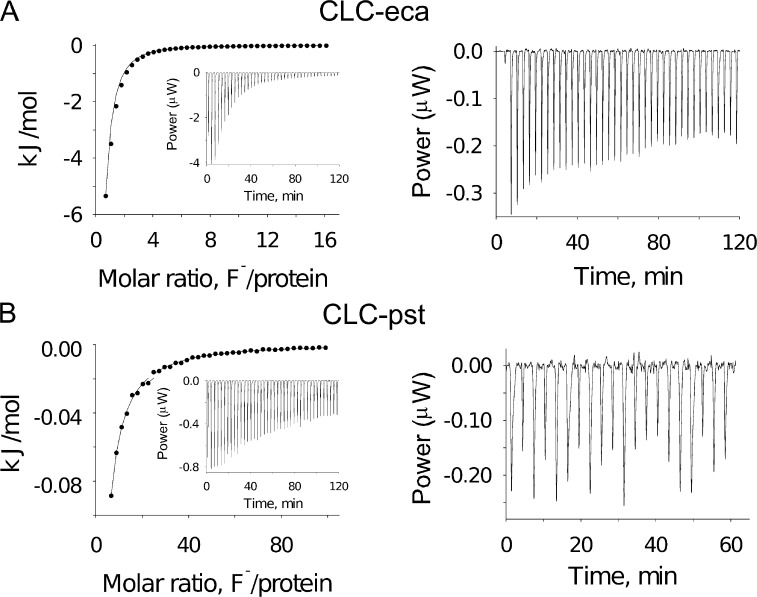

These subclade sequence differences are also reflected in equilibrium anion binding affinity. ITC in detergent micelles, used to measure anion binding to a homologue from each subclade, reveals a striking difference in F− binding affinity between the two (Fig. 3). With a dissociation constant of 0.26 mM, CLC-eca, from the more selective subclade, binds F− nearly 100-fold more tightly than does CLC-pst (Kd ∼20 mM), from the less selective subclade. Cl− binding is unquantifiable for either homologue by direct titration, but F− titration in the presence of 50 mM Cl− produces estimates of F−/Cl− binding selectivity of ∼40 for CLC-eca and 1.2 for CLC-pst, assuming a competitive relationship between the two halides (Fig. 4 and Table 3). These are the only homologues that remain stable in the halide-free conditions required for these titration experiments, so we have not been able to test by direct titration whether these large affinity differences are seen more generally in the subclades. However, F− titration in the presence of excess of Cl− confirms that a third homologue, CLC-eve, binds F− tightly even in the presence of Cl− (Fig. 4), in agreement with its subclade’s F− selectivity.

Figure 3.

ITC data for representative homologues from each subclade. (A and B, left) F− titration of CLC-eca (A) and CLC-pst (B), with solid curves representing a Kd of 0.3 mM and 20 mM, respectively. (right) Cl− raw titration data for corresponding homologues, indicating unquantifiable Kd values >70 mM for both.

Figure 4.

ITC data for F− titrations in the presence of 50 mM Cl− for representative homologues from each subclade. Solid curves represent single-site titrations, with Kd values reported in Table 2.

Table 3.

Thermodynamic parameters for F− binding to CLCF homologues

| Homologue | Condition | K d | ΔH | ΔS |

| mM | kJ/mol | J/mol/K | ||

| CLC-eca | Halide free | 0.26 | −42 | −73 |

| CLC-eca | 50 mM Cl− present | 1.4 (12) | −38 | −72 |

| CLC-eve | 50 mM Cl− present | 0.41 | −34 | −50 |

| CLC-pst | Halide free | 17 | −32 | −72 |

| CLC-pst | 50 mM Cl− present | 56 (22) | −83 | −255 |

F− titration of CLCF homologues that were amenable to the conditions required for the experiment. Parameters were obtained from a fit to a single-site binding isotherm. Values in parentheses indicate the calculated Kd for Cl−, assuming competitive binding.

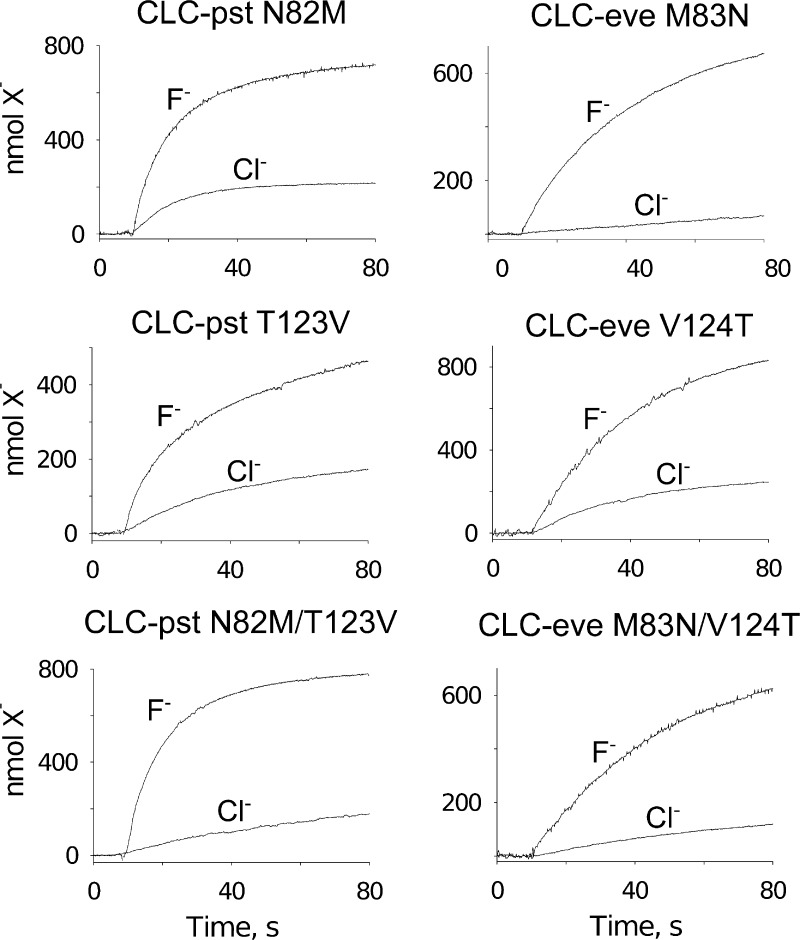

These results raise the possibility that the two CLCF subclade-defining positions, M-V and N-T, might contribute to ion selectivity. Accordingly, we chose a pair of homologues with the widest dynamic range of F− selectivity, the strongly selective CLC-eve (M-V subclade) and the weakly selective CLC-pst (N-T subclade), to test whether swapping side chains would also swap selectivity phenotypes. Mutations at these positions produce changes in absolute transport rates that follow no coherent pattern (Fig. 5 and Table 4). However, the residue interchanges cleanly convert the subclade-associated F− selectivity ratios in both directions, lowering that of CLC-eve and raising that of CLC-pst. The swaps are quantitative in the sense that each mutated homologue achieves a selectivity value characteristic of the other subclade, but they are not entirely symmetric; the single-site V-to-T mutation is sufficient to switch the selectivity of CLC-eve, whereas conversion of CLC-pst requires substitutions at both positions, N-to-M and T-to-V.

Figure 5.

Anion transport in CLCF mutants. Efflux curves determined as in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

F− and Cl− turnover for CLC-pst and CLC-eve mutants

| Subclade | Homologue | F− turnover | Cl− turnover | F−/Cl− ratio |

| s−1 | s−1 | |||

| N-T → M-V | CLC-pst N82M | 1,010 ± 50 | 320 ± 20 | 2.6 ± 0.4 |

| N-T → M-V | CLC-pst T123V | 430 ± 10 | 130 ± 10 | 3.7 ± 0.8 |

| N-T → M-V | CLC-pst N82M/T123V | 1,030 ± 70 | 120 ± 10 | 9.2 ± 1.2 |

| M-V → N-T | CLC-eve M83N | 270 ± 10 | 30 ± 0 | 11.2 ± 1.2 |

| M-V → N-T | CLC-eve V124T | 310 ± 10 | 170 ± 20 | 1.9 ± 0.2 |

| M-V → N-T | CLC-eve M83N/V124T | 190 ± 10 | 70 ± 10 | 2.9 ± 0.4 |

Turnovers on the indicated mutants were measured as described in legend to Table 2. Ratios were calculated from each set of independent trials (n = 6).

These results raise a disturbing question: how can such weak F−/Cl− selectivity, 10-fold at best, support the biological purpose of these F− exporters, given the 1,000-fold greater abundance of Cl− in the aqueous biosphere? During the course of these experiments, we noted an initially perplexing observation that may illuminate this question: if transport measurements are performed with K+ in the efflux medium instead of Na+, all homologues tested, regardless of subclade, display extremely high F− selectivity, as originally reported (Stockbridge et al., 2012). Indeed, under this high-K+ condition, F− flux rates remain high, whereas Cl− transport is completely abolished as far as we can discern (Fig. 6 and Fig. S2), placing a lower limit of ∼80 on F−/Cl− selectivity. Two obvious alternatives offer themselves to explain this striking effect: that Cl− movement through the transport protein specifically requires Na+ as a coactivator or that this anion needs the large negative voltage set by Vln in the presence of a large K+ gradient to be driven out of the liposomes.

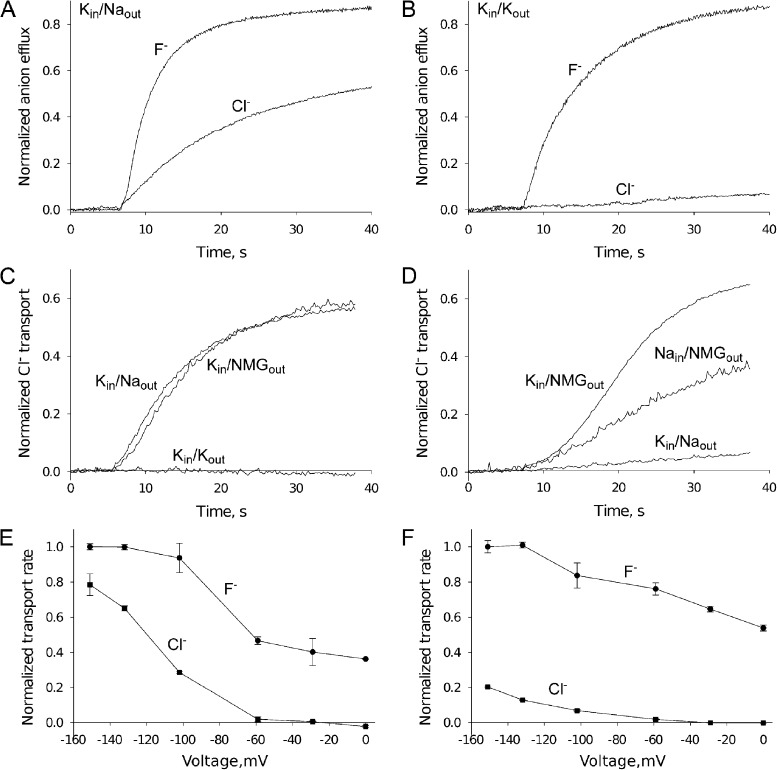

Figure 6.

Voltage-dependent anion transport of CLCFs. (A and B) Anion efflux by CLC-pst with K+/Na+ conditions indicated. Efflux time courses are normalized to the values after disrupting the liposomes with detergent. (C and D) Cl− transport via CLC-pst monitored by light scattering, with either Vln (C) or gA (D) added to initiate transport. (E and F) Voltage dependence of anion transport for CLC-pst and CLC-eca, respectively. Initial rates for F− and Cl− were normalized to the initial rate for F− transport at −151 mV. Voltage values are calculated from the K+ Nernst potential set by varying external K+ with fixed internal K+.

These explanations are readily distinguished experimentally. A specific Na+ requirement for Cl− transport is ruled out by testing transport with external Na+ replaced by a large organic cation, NMG+, while maintaining high negative voltage. Under this Na+-free condition, CLC-pst transports Cl− at rates comparable with those in Na+ (Fig. 6 C). To further test the idea that voltage drives Cl− efflux, transport was initiated by a different ionophore, gA, which conducts both K+ and Na+ but not NMG+ (Finkelstein and Andersen, 1981). With either K+ or Na+ as the internal cation, gA-induced Cl− efflux is observed only if NMG+ is the external cation (Fig. 6 D). Thus, Cl− transport occurs only at high negative voltage, regardless of the particular ions or ionophores used to establish that voltage. These experiments show that Cl− requires a large electrical driving force to permeate CLC-pst, whereas F−, the physiological substrate, can move through the protein at both low and high voltage.

The voltage dependence of anion transport was quantified for a homologue from each subclade. The results show, unsurprisingly, that F− efflux increases from its zero-voltage value at more negative potentials. In contrast, Cl− transport is unobservable at zero voltage and can be seen only at voltages negative to −60 mV (Fig. 6, E and F). Because all six homologues studied here fail to transport Cl− at zero voltage, we imagine that this voltage-dependent selectivity is a feature of the entire CLCF family. This unusual CLCF selectivity phenomenon may be physiologically significant, as discussed below.

DISCUSSION

Phylogenetic analysis of the CLCF antiporters reveals a divergence of the family into two subclades. Aligned sequences of these subclades identify two strictly cosegregating positions, the M-V and N-T sites, near equivalent anion-binding regions in the greater CLC superfamily. Six CLCF homologues show subclade-associated differences in F− selectivity for both transport kinetics and equilibrium binding. These intricately linked processes reflect different molecular events, so the observed correspondences in their selectivities are not expected to show full quantitative agreement. We suppose that these six homologues reflect properties of the subclades in general because they were selected for study only by the criterion of biochemical tractability, without regard for their particular functional behaviors.

These facts arouse suspicions that the covarying residues may have a direct role in the selectivity displayed by these transporters, suspicions buttressed by conversion of selectivity phenotype by residue swaps at these two positions. In the absence of an experimental high-resolution structure of a CLCF protein, we cannot productively speculate on the mechanism by which these two residues exert their effects on F− transport and binding, especially because homology models of CLCFs lack the precision required to understand the up-close coordination chemistry underlying small-ion selectivity phenomena.

Voltage-dependent rates of ion movement are generally expected for electrogenic transporters of all types, but the exceptionally strong voltage dependence of F−/Cl− selectivity in CLCFs is, as far as we are aware, unprecedented. Little may be inferred mechanistically from this observation, except to suppose that once bound, Cl− faces energetic barriers in the transport cycle that can be overcome only by a large electrostatic push, barriers not encountered by the physiological anion. This idea is consistent with the observation that at zero voltage, where CLC-pst shows nonselective binding, all homologues are highly selective in transport. An alternative explanation to consider is that voltage dependence is somehow related to the gating phenomenon described for the human Cl−/H+ exchanger CLC-5 (Smith and Lippiat, 2010; De Stefano et al., 2013). We are inclined away from such an explanation, however, because in electrophysiological experiments (Stockbridge et al., 2012), CLCF transporters do not display any voltage-dependent gating kinetics such as those described for CLC-5. The voltage dependence of F− selectivity does provoke speculations about its biological role, however. We imagine that in exporting F−, the transporter should avoid competition by Cl−, which at 10–50-mM levels is roughly 1,000-fold higher in bacterial cytoplasm (Schultz et al., 1962). Because of the anomalously high pKa of hydrofluoric acid, F− toxicity is most dangerous to bacteria in acidic niches (Baker et al., 2012; Stockbridge et al., 2013), wherein F−/H+ antiporters are well suited to operate by driving F− expulsion with the proton gradient. Under such acid-challenge conditions, the bacterial inner membrane is expected to depolarize, possibly to a voltage positive to −60 mV, where Cl− cannot engage with the F− transport pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A.E. Brammer was supported by National Institutes of Health training grant T32-GM007596.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

David C. Gadsby served as guest editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- DM

- n-decyl-β-d-maltopyranoside

- FCCP

- carbonylcyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone

- gA

- gramicidin A

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- NMG+

- N-methyl-d-glucamine

References

- Accardi, A., and Picollo A.. 2010. CLC channels and transporters: proteins with borderline personalities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1798:1457–1464. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accardi, A., Lobet S., Williams C., Miller C., and Dutzler R.. 2006. Synergism between halide binding and proton transport in a CLC-type exchanger. J. Mol. Biol. 362:691–699. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.L., Sudarsan N., Weinberg Z., Roth A., Stockbridge R.B., and Breaker R.R.. 2012. Widespread genetic switches and toxicity resistance proteins for fluoride. Science. 335:233–235. 10.1126/science.1215063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cametti, M., and Rissanen K.. 2009. Recognition and sensing of fluoride anion. Chem. Commun. (Camb.). (20):2809–2829. 10.1039/b902069a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, S., Pusch M., and Zifarelli G.. 2013. A single point mutation reveals gating of the human ClC-5 Cl−/H+ antiporter. J. Physiol. 591:5879–5893. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.260240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutzler, R., Campbell E.B., and MacKinnon R.. 2003. Gating the selectivity filter in ClC chloride channels. Science. 300:108–112. 10.1126/science.1082708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, R.C. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, A., and Andersen O.S.. 1981. The gramicidin A channel: a review of its permeability characteristics with special reference to the single-file aspect of transport. J. Membr. Biol. 59:155–171. 10.1007/BF01875422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouy, M., Guindon S., and Gascuel O.. 2010. SeaView version 4: A multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27:221–224. 10.1093/molbev/msp259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon, S., Dufayard J.F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., and Gascuel O.. 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59:307–321. 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, A.J., Huster D., Gawrisch K., and Nossal R.. 1999. Light scattering characterization of extruded lipid vesicles. Eur. Biophys. J. 28:187–199. 10.1007/s002490050199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S., Smith K.D., Davis J.H., Gordon P.B., Breaker R.R., and Strobel S.A.. 2013. Eukaryotic resistance to fluoride toxicity mediated by a widespread family of fluoride export proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:19018–19023. 10.1073/pnas.1310439110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, H.H., Stockbridge R.B., and Miller C.. 2013. Fluoride-dependent interruption of the transport cycle of a CLC Cl−/H+ antiporter. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9:721–725. 10.1038/nchembio.1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C. 2006. ClC chloride channels viewed through a transporter lens. Nature. 440:484–489. 10.1038/nature04713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picollo, A., Malvezzi M., Houtman J.C., and Accardi A.. 2009. Basis of substrate binding and conservation of selectivity in the CLC family of channels and transporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16:1294–1301. 10.1038/nsmb.1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, S.G., Wilson N.L., and Epstein W.. 1962. Cation transport in Escherichia coli. II. Intracellular chloride concentration. J. Gen. Physiol. 46:159–166. 10.1085/jgp.46.1.159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.J., and Lippiat J.D.. 2010. Voltage-dependent charge movement associated with activation of the CLC-5 2Cl−/1H+ exchanger. FASEB J. 24:3696–3705. 10.1096/fj.09-150649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockbridge, R.B., Lim H.H., Otten R., Williams C., Shane T., Weinberg Z., and Miller C.. 2012. Fluoride resistance and transport by riboswitch-controlled CLC antiporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:15289–15294. 10.1073/pnas.1210896109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockbridge, R.B., Robertson J.L., Kolmakova-Partensky L., and Miller C.. 2013. A family of fluoride-specific ion channels with dual-topology architecture. eLife. 2:e01084. 10.7554/eLife.01084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden, M., Accardi A., Wu F., Xu C., Williams C., and Miller C.. 2007. Uncoupling and turnover in a Cl−/H+ exchange transporter. J. Gen. Physiol. 129:317–329. 10.1085/jgp.200709756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zifarelli, G., and Pusch M.. 2007. CLC chloride channels and transporters: a biophysical and physiological perspective. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 158:23–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.