Abstract

Background and Aim:

The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMJD) in the Iran/Iraq war veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 120 subjects in the age range of 27 to 55 years were included; it included case group (30 war veterans with PTSD) and three control groups (30 patients with PTSD who had not participated in the War, 30 healthy war veterans, and 30 healthy subjects who had not participated in the War). All subjects underwent a clinical TMJ examination that involved the clinical assessment of the TMJ signs and symptoms.

Results:

The groups of veterans had high prevalence of TMJD signs and symptoms vs. other groups; history of Trauma to joint was significantly higher in subjects who had participated in the war compare with subjects who had not participated in the war (P = 0.0006). Furthermore, pain in palpation of masseter, temporal, pterygoideus, digastric, and sternocleidomastoid muscles in the groups of veterans was significantly greater than other groups (P < 0.0001). Clicking noise during mouth chewing was significantly different between groups (P = 0.01). And, there was significant difference in the frequencies of maximum opening of the mouth between groups (P = 0.001).

Conclusion:

The results of this study showed that subjects’ war veterans with PTSD have significantly poorer TMJ functional status than the control subjects.

Keywords: Post-traumatic stress disorder, temporomandibular disorders, war stress

INTRODUCTION

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a chronic psychiatric illness that may arise after an individual experienced or witnessed a frightening event (e.g. military combat, violent personal attack, serious car or airplane accident)[1] and was first defined in the third edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Usually, PTSD symptoms begin around six months after the event, though they can happen years later.[2] There is growing evidence that PTSD has an exclusively significant role in veterans’ physical health outcomes.[3] Studies of Vietnam veterans,[4] World War II and Korean veterans,[5] Gulf War I veterans,[6] and Iraq and Afghanistan War soldiers[7,8] have found a relationship between PTSD and physical health outcomes. The prevalence of PTSD among combat veterans is between 15% and 60%,[9,10] and is two to four times higher in disabled combat veterans than in other veterans.[11,12]

It is considered that persons exposed to stress are under increased risk of the incidence of TMDs, as stress and unpleasant life experiences are more frequent in patients with dysfunction.[13] TMDs can be strongly associated with depression and environmental stress;[14] also, TMDs patients report that their symptoms increase during stressful situations.[15] One of the potential causes of PTSD is war. War is the condition that includes stress of varying intensity and duration and because frequent, repetitive, cumulative effects are present, war is set as a catastrophic stressor.[15]

Previous studies reported high prevalence of signs and symptoms of TMDs[16] and temporomandibular joint[17] in war veterans who suffered from PTSD. Uhac et al. (2003)[18] showed that correlation exists between war stress and temporomandibular disorders. Limited function, sounds, and pain in the TMJ are common symptoms of TMDs. Therefore, this study was designed to determine the prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMJD) in the Iran/Iraq war veterans suffering from PTSD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was performed over a nine-month period (April to December 2008). We collected and reviewed the data of 120 subjects in the age range of 37 to 55 years; it included 60 patients who received Psychotherapy in four different clinics in Isfahan (Case group; 30 war veterans and Control group I; 30 had not participated in the War), and 60 healthy subjects with no mental disorders (Control group II; 30 war veterans and Control group III; 30 had not participated in the War).

The diagnosis of the symptoms of PTSD was made by a psychiatrist on the basis of a structured clinical interview according to DSMIV criteria,[19] previous medical documentation, and data obtained from a patient's family.

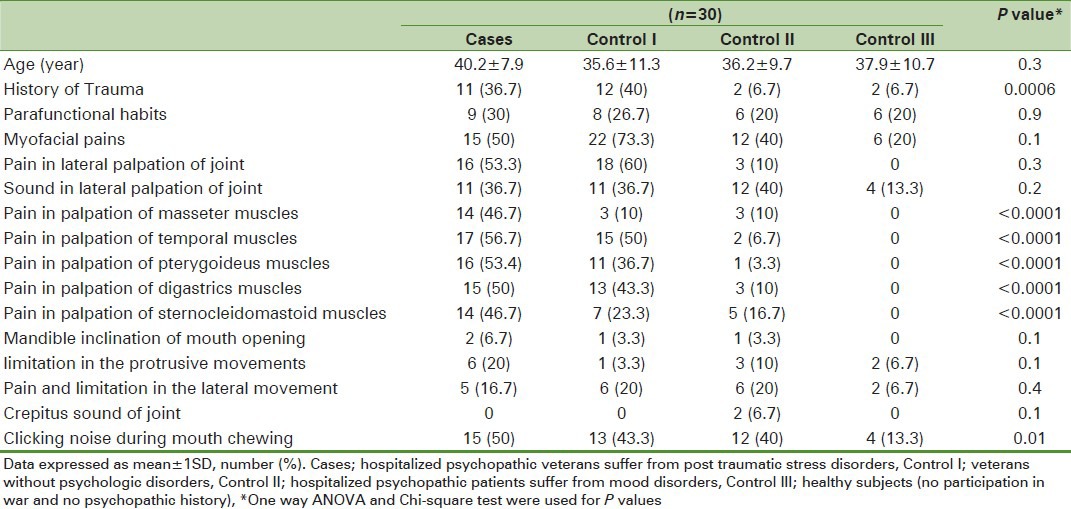

The structured questions were used to evaluate the participants’ characteristics: Age, sex, level of education, and marital status. Most of the subjects had high school education (70%) and were married (90%). Also, all subjects underwent a clinical TMJ examination that involved the clinical assessment of the following TMJ signs and symptoms: History of Trauma to joint, pain in palpation of masseter, temporal, pterygoideus, digastric, sternocleidomastoid muscles [Figure 1], clicking noise during mouth chewing, parafunctional habits, myofacial pains, pain in lateral palpation of joint, sound in lateral palpation of joint [Figure 2], mandible inclination of mouth opening, limitation in the protrusive jaw movements [Figure 3], pain and limitation in the lateral movement, and crepitus sound of joint; and prepared questionnaire completed [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Sternocleidomastoid muscle palpation

Figure 2.

Sound assessment in lateral palpation of joint

Figure 3.

Assessment of protrusive jaw movements

Table 1.

Sample of questionnaire

All analyses were done with the use of PASW software (version 18). Data are presented as mean ± 1SD or number (percentage) as appropriate. One-way analysis of variance test was used to compare the mean of age between the study groups. The frequency of each 5 of the 17 symptoms of PTSD was compared between the groups using Chi-square test. Pvalue of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

It should be consider that before through the study, the researcher talked about the project, its aims and process for all the participants. They were asked to participate in the study if they liked. Moreover, informed consent was obtained and the study was approved by local ethic committee of Islamic Azad University (Khorasgan Branch).

RESULTS

Of the 120 participants, all subjects in the case group (30) and control groups (90) were included in the analysis. The mean age of patients was 44.2 ± 15.1 years [27-55], all patients were male. As shown in Table 2, the groups of veterans had high prevalence of TMJD signs and symptoms vs other groups, history of Trauma to joint was significantly higher in subjects who had participated in the war compared with subjects who had not participated in the war (P = 0.0006). Furthermore, pain in palpation of masseter, temporal, pterygoideus, digastric, and sternocleidomastoid muscles in the groups of veterans was significantly greater than other groups (P < 0.0001). Clicking noise during mouth chewing was significantly different between groups (P = 0.01). Differences between the subjects of four groups with regard to the frequency of other symptoms (parafunctional habits, myofacial pains, pain in lateral palpation of joint, sound in lateral palpation of joint, mandible inclination of mouth opening, limitation in the prevent movements, pain and limitation in the lateral movement, and crepitus sound of joint) were not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Characteristics and symptoms reported by the subjects in the study groups

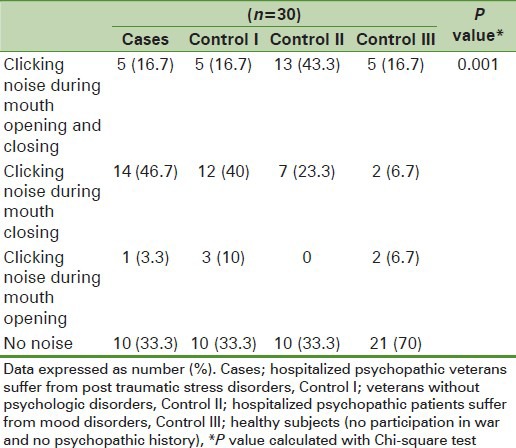

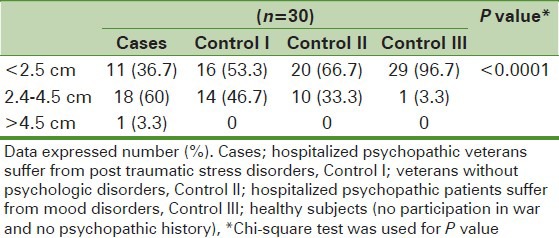

Clicking noise during mouth opening and closing is stratified for the presence or absence of click sounds in Table 3. We performed Chi-square analyses to examine whether frequencies of the clicking noise were statistically significant for the study groups; and found significant difference between groups (P = 0.01). Table 4 shows the maximum opening of the mouth of the study population. The majority of subjects had maximum opening of the mouth less than 2.5 cm. Forty-three subjects had maximum opening of the mouth between 2.5 to 4.5 cm and one person in hospitalized psychopathic veterans had maximum opening of the mouth more than 4.5 cm. Chi-square test showed that there was significant difference in the frequencies of maximum opening of the mouth between groups (P = 0.001).

Table 3.

Clicking noise during mouth opening and closing in the study groups

Table 4.

Maximum opening of the mouth in the study groups

DISCUSSION

TMD is one of the most common disorders in orofacial region that is usually associated with pain, unusual sounds, and discomfort in mastication. Psychological factors are factors affecting the masticatory system and TMJ, and are able to constrain parafunctional habits.[20,21,22,23]

Deleeuw et al.[24] concluded that individuals with chronic TMD were assessed with high levels of anxiety in psychiatric tests and it was indicated that pain in face and head was associated with stress. It was concluded the same as this study that stress can act as an important factor affecting on incidence of TMD.

Manfredino et al.[25] indicated that the level of anxiety in individuals having orofacial pain were significantly higher (P = 0.001) that matches the results of this study.

Matsuka et al.[26] performed a comparison between different factors initiating TMD and concluded that psychological factors are the most important among all factors.

Bonjardim et al.[27] investigated the facial deformities and TMJ disorders and concluded that there is a significant relationship between stress and unusual sound of TMJ (P = 0.002)2 that matches the results of this study.

All the conducted studies indicated that stress is an effective factor for the incidence of TMJ disorders.

On the other hand, the larger the exposure to war traumatic experience, the larger is the relationship between war trauma and psychiatric disorders.[20] Depending on the methods used for data gathering, the prevalence of PTSD in the general population ranges from 1 to 14% and in war veterans groups is from 3 to 58%. The prevalence of PTSD among war veterans in Croatia ranged from 11.1 to 24.2% and during the Vietnam War 15.2% of American soldiers developed PTSD.[19] This study examines the association of PTSD and TMJD in war veterans and the results indicate that war veterans had high prevalence of TMJD signs and symptoms vs. other subjects who had not participated in the war.

Our study shows that war veterans’ patients with PTSD suffer from pain in palpation of masseter muscles, temporal muscles, pterygoideus muscles, digastric muscles, and sternocleidomastoid muscles. Also, clicking noise during mouth opening and closings and maximum opening of the mouth was significantly difference between groups.

Uhak et al. (226)[16] studied the prevalence of TMJ disorders in war veterans with PTSD and found that TMJ disorder is significantly higher in war veterans vs control group that did not have participant in war and PTSD that exactly same with the result of our study.

Muhvic-Urek et al.[17] have explored the association between prevalence of signs and symptoms of TMDs and PTSD and found that TMD is more prevalent among war veterans’ patients with PTSD than control subjects.

Several studies reported high prevalence of signs and symptoms of TMDs, and high dysfunction of the stomatognathic system among war veterans’ PTSD patients.[17,18] These results are agreement with the present study showed that TMJD as a common symptom of TMDs is more prevalent in war veterans’ patients with PTSD.

Uhac et al. (2003)[18] showed that 82% of the subjects with PTSD had symptoms of dysfunction compared with 24% of the subjects in the healthy control group. This was less than present study with 36.7% of the patients with PTSD compared with 13.3 to 40% of the subjects in the healthy control groups.

Afari and Wen (2010)[28] studied the relation between PTSD sign and TMJ pain and found that there is a strong relationship between them that is consistent with our result.

Deleeuw and Bertoli (2009)[29] studied the prevalence of PTSD symptoms among patients with orofacial pain and concluded that these signs are more frequent in this group compared with other people as our study show it too.

Results of the present study lead to the conclusion that war veteran subjects with PTSD have significantly poorer TMJ functional status than the control subjects, and further attention should be given to the prevention and to the pain release in cases of temporomandibular disorders. More regard therefore should be given to studies that use direct and indirect measures of variables such as quality of life.

The current results also suggest the need to closely coordinate medical and mental healthcare, which may be essential for veterans with PTSD sufferers in order to decrease their risk of dental caries and oral mucosal diseases.

Some of the drawback and limitation of the study were inclusion of appropriate communication with psychopathic patient, poor cooperation during clinical examination, and psychiatric drug treatment that was inevitable. Also, the accuracy of psychopathic patient conversations was not reliable and it was a confounding factor that was needed to repeat examination to reduce it.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank all the veterans who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.4th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 1994. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 2.3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 1980. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnurr PP, Green BL. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. Trauma and Health: Physical Health Consequences of Exposure to Extreme Stress. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckham JC, Moore SD, Feldman ME, Hertzberg JR, Kirby AC, Fairbank JA. Health status, somatiziation and symptom severity of posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1565–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnurr PP, Spiro A. Combat disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and health behaviors as predictors of self-reported physical health in older veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:353–9. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner AW, Wolfe J, Rotnitsky A, Proctor SP, Erickson DJ. An investigation of the impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on physical health. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:41–55. doi: 10.1023/A:1007716813407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakupcak M, Luterek J, Hunt S, Conybeare D, McFall M. Posttraumatic stress and its relationship to physical health functioning in a sample of Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans seeking post deployment VA health care. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:425–8. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31817108ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoge CW, Terhakopian A, Castro CA, Messer SC, Engel CC. Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with somatic symptoms, health care visits and absenteeism among Iraq War veterans. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:150–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stretch RH. Psychosocial readjustment of Canadian Vietnam veterans. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:188–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orner RJ. Post-traumatic stress syndrome among British veterans of the Falkland war. In: Wilson JP, Raphael B, editors. International handbook of traumatic stress syndromes. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 305–11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Jordan BK, Hough RL, Marmar CR, et al. Assessment of PTSD in the community – prospects and pitfalls from recent studies of Vietnam veterans. Psychological assessment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;3:547–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gregurek R, Vukuši H, Bareti V, Potrebica S, Krbot V, DZidi I, et al. Anxiety and post traumatic stress disorder in disabled war veterans. Croat Med J. 1996;37:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okeson JP. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2003. Management of temporomandibular disorder and occlusion; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sipilä K, Veijola J, Jokelainen J, Järvelin MR, Oikarinen KS, Raustia AM, et al. Association between symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and depression: An epidemiological study of the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Cranio. 2001;19:183–7. doi: 10.1080/08869634.2001.11746168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suvinen TI, Hanes KR, Gerscham JA, Reade PC. Psychophisical subtypes of temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 1997;11:200–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uhac I, Kovac Z, Muhvić-Urek M, Kovacević D, Francisković T, Simunović-Soskić M. The prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Mil Med. 2006;171:1147–9. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.11.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muhvić-Urek M, Uhac I, Vuksić-Mihaljevi Z, Leović D, Blecić N, Kovac Z. Oral health status in war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Oral Rehabil. 2007;34:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2006.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uhac I, Kovac Z, Valentic-Peruzovic M, Juretic M, Moro LJ, Grzic R. The influence of war stress on the prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30:211–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM. Psychometricproperties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychol Assess. 1999;11:124–33. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg M, Glick M. 12th ed. England: BC Decker Inc; 2010. Burkets Oral Mediceni Diagnosis and Treatment; pp. 271–307. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rugh JD, Wood BJ, Dahlstrom L. Temporomandibular disorders: Assessment of psychological factors. Adv Dent Res. 1993;7:127–36. doi: 10.1177/08959374930070020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rollman GB, Gillespie JM. The roll of psychosocial factor in temporo mandibular disorders. J Curr Rev Pain. 2003;4:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s11916-000-0012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stock still JW, Callahan CD. Personality hardiness anxiety and depression as contructs of interest in the study of temporomandibular disorders. J Craniomandibular Disord. 2007;15:129–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deleeuw R, Bertoli E. Prevalence of traumatic stressor in patient with temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manfredino D, Bandethini AB, Cantini E. Mood and anxiety Psychopathology and temporomandibular disorder. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;41:933–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuka Y, Yatan H, Kuboki T. Temporomandibular disorders in the adult population. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;24:158–62. doi: 10.1080/08869634.1996.11745962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonjardim LR, Gaviao MB, Pereira LJ. Anxiety and depression in adolescent and their relationship with mandibular disorders. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;38:347–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Afari N, Wen Y. Are post traumatic stress disorder symptoms and temporomandibular pain associated? Finding from a community-based twin rwgistry. J Orofac Pain. 2008;22:41–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deleeuw R, Bertoli E. Prevalence of post traumatic stress disorder symptoms in orofacial pain patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2005;99:558–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]