Abstract

Background:

There has been an increase in institutional delivery rates in India in the recent years. However, in areas with high institutional delivery rates, most deliveries (>50%) occur in private institutions rather than in government facilities where zero expense delivery services are being provided.

Aim:

This study aimed to understand, from the community health volunteers’ viewpoint, the reasons for underutilization of zero expense delivery services provided in government health facilities.

Materials and Methods:

Five Focused Group Discussions (FGD) were conducted among Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHAs) of a Primary Health Centre (PHC) in Dayalpur village, Haryana in December 2012. Participants were asked to articulate the possible reasons that they thought were responsible for expectant mothers not choosing to deliver in government health facilities. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Result:

The commonly stated reasons for underutilization of government health facilities for delivery services were lack of quality care, abominable behaviour of hospital staff, poor transportation facilities, and frequent referrals to higher centres.

Conclusion:

This study reflected the necessity for new policies to make government health facilities friendlier and more easily accessible to clients and to make all government hospitals follow a minimum set of standards for providing quality care.

Keywords: ASHA, Delivery services, India, National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), Qualitative study, Utilization of government health facilities

Introduction

India has achieved sizeable reductions in Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) and Neonatal Mortality Rate (NMR) in the last decade but there is still a lot of ground to cover in order to achieve the related Millennium Development Goals (MDG) by 2015.[1,2] The major objectives of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) are to achieve an MMR of 212 and NMR of 35 per 1000 live births.[3,4] Promotion of institutional deliveries is an important strategy for achieving these objectives. Under NRHM the federal government had launched several schemes such as the Janani Suraksha Yojna (JSY), ASHA program, and Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakarm (JSSK) to achieve this goal. The Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) program was launched to promote institutional delivery among pregnant women in rural areas of India. ASHAs are trained female community health volunteers selected from within the community and by the community leaders themselves. They receive performance-based incentives for promoting immunization, institutional delivery, and other health related activities.[5,6,7,8] In addition, several state governments have devised their own innovative schemes to increase institutional deliveries such as the Delivery Hut Scheme launched by the Haryana government in 2008. Under this scheme all delivery related services were provided free of cost in government health facilities.[9]

Institutional delivery rates have been increasing across all states in India and majority of these institutional deliveries occur in government health facilities. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS 3), 2005-06 reported that 18% of institutional deliveries took place in government health facilities.[10] The District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS 3), 2007-08 reported that 47% of all deliveries took place in government health facilities as compared to 1% in private facilities at the country level.[11] A few researchers have investigated the lower utilization of government health facilities and found that affordability, availability, acceptability, accessibility, and financial constraints were common reasons in areas where the proportion of deliveries attended by Skilled Birth Attendants (SBA) were high.[12,13] Similarly the institutional delivery rates in our study area such as Primary Health Centre (PHC), Dayalpur, Faridabad, Haryana reached 92% during 2012. Among the institutional deliveries, only 52% occurred in government facilities where zero expense services are being provided as per government mandate (Unpublished data, annual report of PHC Dayalpur, available from authors on request). Based on this background, we conducted a qualitative study among the ASHA workers of our PHC to identify the reasons that prevent pregnant women from utilizing government health facilities for delivery. The current study was conducted among ASHAs because they act as important players in deciding the place of delivery and also accompany patients to health facilities. They get incentives only if patients deliver in government or government accredited health facilities. Since ASHAs form part of the same community they serve, their perception about government, health facilities could serve as a proxy for community perceptions. Their perceptions are easier to obtain and act as a first step in understanding the broader underlying issues for poor utilization of zero expense services available in government health facilities.

Material and Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles stated in Helsinki declaration. Anonymity of the participants and confidentiality of information were maintained.[14] Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants. The present study was conducted as part of a routine activity and in the context of improving health service delivery. The study area was a PHC catering to 46,000 residents in 17 villages of Faridabad district, Haryana.[15] This PHC is a part of the Intensive Field Practice Area (IFPA) of the Centre for Community Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi. A qualitative study was conducted among the ASHA workers of the PHC. There were 43 ASHAs under the PHC, all of whom had a minimum work experience of 5 years. One of their major functions was to promote institutional deliveries in government health facilities. Five Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), each comprising of eight to nine participants were conducted during December 2012. The major domain covered in the FGD was reasons for underutilization of government health facilities by expectant mothers. We explored the issues related to infrastructure, cost, accessibility, and staff behaviour. The medical officer in-charge moderated the discussions.

Statistical analysis

Interview transcripts and documents were analyzed in English. In the first phase, data analysis was mainly inductive. In a second phase, to enhance robustness of the analysis emerging themes were constructed into an utilization model.

Results

This study was able to bring out the major factors responsible for underutilisation of government health facilities from the viewpoint of ASHA workers. Many studies have reported that ASHAs have been considered major change agents responsible for increasing institutional delivery rates under NRHM.[8,16,17,18] Their opinion on why expectant mothers do not prefer to avail delivery services from government health facilities was important because these health volunteers belong to the community they cater to and their views were likely to represent the views of the community as a whole.

Lack of quality care in government health facilities

Lack of quality care in government health facilities was the most frequent reason given for low utilization. The problems of rueful hygiene in delivery rooms and unkempt bed linens were common in government facilities. Improper cleaning of delivery instruments and delivery table also added to the bad experience of patients. Besides hygiene, concerns regarding patients’ privacy were also emphasized as an important determinant of low utilization. Patients felt very embarrassed when they were examined in a room without privacy.

“…a staff nurse was examining my patient naked and suddenly a male doctor came in... it was very embarrassing for my patient…my patient suggested that there must be curtains around the examination table.”

- Participant number 7

Gender of the treating doctor was also an important issue for some patients. Some of the patient's relatives objected if the attending doctor was a male. In addition, in government hospitals no more than one attendant was allowed to stay with the patient. This created a sense of insecurity among the relatives about the care of their patient.

The issue of delay in delivery of the baby in government hospitals was stressed by the ASHAs. Private doctors hastened the delivery process by medications, which was quoted as a relief-giving factor for the expectant mother and her relatives. However, this was not the situation in the government facility where labour induction was as per the guidelines. Here ASHAs emphasized their point by comparing the government health facility with the private ones. A few ASHAs also explained that rich people made it a matter of prestige to deliver in private hospitals.

“In private hospitals, they start fluids and give injections and baby is delivered very fast… in case of delay they immediately do operation. They never let your patient bear excess pain… but in government hospital they allow delivery to progress naturally.”

- Participant number 39

Misconduct of hospital staff

Poor demeanour of staff in government facilities often resulted in disconsolate experiences for patients and relatives. This factor mainly came into play when ASHAs motivated multigravida patients because they had prior interaction with such staff. One of the participants considered this as the most non-negotiable issue in promoting institutional deliveries.

“Many of my patients who delivered their previous baby in government hospitals do not want to deliver their next baby in a government hospital... they said that behaviour of hospital staff was very inhuman and they had no respect for life.”

- Participant number 43

Staff nurses of government health facilities failed to adequately explain the details of the procedure/examination process that was to be performed on the patients.

“My patient was asked very bluntly to remove her clothes and examination was done without explaining the procedure…”

- Participant number 35

Participants felt that only those mothers who had had a good experience with nurses during the first delivery would prefer to go to government hospitals during the subsequent pregnancies and deliveries. In some government hospitals, nurses misbehaved even with the ASHA workers as they did not consider them to be a part of the system. It was not just the past travails of the pregnant women but also that of the ASHA worker, which prevented utilization of government health facilities.

Lack of transport facilities

Lack of proper facilities for transporting pregnant women from their homes to government hospitals was considered to be an important factor for low utilization of services. ASHAs emphasized that even though ambulance facilities were available, there was considerable delay between calling the control room and the ambulance reaching their homes. They said it decreased the faith of caretakers on the ASHAs and the ambulance services, which in turn translated into preferential delivery at private facilities.

“One of my patients wanted to go to the PHC… I informed the ambulance... it took some time... Meanwhile she started having frequent pains, family members got apprehensive and took her to a private facility… they said that when your services are not good then why you asked us to deliver in the government hospital.”

- Participant number 5

Some of the private hospitals also provided free ambulance for transporting patients to their hospitals. They usually solicited patients by using agents such as dais, traditional healers, Anganwadi workers, and rarely ASHAs and for this monetary incentives were provided to them.

“A few ASHAs and Anganwadi workers have liaison with private hospitals and they convince the patients to go for delivery in their hospital and they get money from the hospital for that.”

- Participant number 3

In addition to non-availability of ambulance services in the immediate vicinity, dismal condition of village roads also caused the delay. There have been instances where the delivery occurred in the ambulance itself due to the various delays.

Even though lack of timely accessibility to transportation facility ranked lower among the reasons for low utilization, the participants emphasized that ameliorating this factor alone could enhance the utilization to a significant level.

Frequent referrals from government hospitals

Frequent referrals to higher centres, especially after a considerably prolonged stay at the PHC, was considered as important deterrent for future deliveries in PHCs. This affected not only the decision of that particular family but also others in their neighborhood.

Patients from the PHC would be referred either to a secondary or tertiary level government facility. This referral process caused the patient and her family significant distress. This made people think that government facilities have a callous attitude towards the patients.

“After three hours of admission in the local PHC, she started bleeding and the doctor advised to go to a bigger hospital… there they referred her to an even bigger hospital… the bleeding increased and she gave birth to a dead baby in a private hospital. Her relatives told me that your hospital has cheated us.”

- Participant number 22

Other less commonly stated reasons for underutilization were non-availability of staff at the facility especially on holidays, lack of medicines and supplies, corruption, traditional practices followed by mother-in-law, and promise of male child by traditional dais.

Discussion

Several studies have examined the barriers to utilization of maternal care services from the viewpoint of mothers, community members, and community health volunteers. Largely, most of these studies were from areas with low institutional delivery rates.[19,20,21] To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in India that has attempted to explore the reasons for underutilization of government health facilities in a setting with high institutional delivery rates in spite of the provision of zero expense delivery services. The findings of the current study were not much different from the findings of studies done in areas with lower institutional delivery rates. This study suggested that inadequate quality of care, misconduct of health personnel, poor transport facilities and frequent referrals were the major determinants of lower utilization of government facilities even though services were available free of cost.

Inadequate quality of care was the most common issue raised by the ASHA workers. Pandey N carried out a qualitative study in rural Uttar Pradesh, India, which showed that less people visited PHCs because they prefer the services provided at private hospitals.[22] This finding was consistent with the results of our study as many ASHA workers reported that people preferred private hospitals because of better services and the importance given to patient privacy. Lower utilization of free services by rich people that was found in this study has also been reported by Pandey N and Kesterton AJ et al.[22,23] This finding highlighted the need for improvement in the quality of care provided at government hospitals. Uniform implementation of a standard basic level of care at all government facilities is the need of the hour. Accreditation of government facilities against a set standard should be explored as an option for improving the quality. Regular in-service training of Skilled Birth Attendants (SBA) is also necessary for maintaining quality care.

Our study underscored the fact that availability of free services alone was not sufficient to lure the community to government facilities, but supportive and respectful behavior of attending staff was equally important. Proper explanation of procedures and good mannered behavior with relatives were identified, as major felt needs. Effect of previous experience on the choice of place of delivery was also reported by other studies.[18,19,20,21] Pre-placement orientation training provided to doctors, nursing staff, Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM), and health workers should include modules on communication skills and the importance of public relations. Many staff in government hospitals displayed ill-mannered behaviour probably because of the heavy workload, inadequate salary for contractual staff and the complacent and lackadaisical attitude of permanent staff. The hospital in-charge should motivate hospital staff to assume a friendly demeanour and provide an amicable environment for clients coming to the hospital. Celebration of a special week based on themes like patient privacy and pleasing bedside manners could be useful in sensitizing hospital staff on these issues.

Lack of proper and timely transport facility and poor road conditions in some villages were highlighted as a crucial concern especially in case of deliveries occurring at homes, where woman wanting to deliver in a government hospital were not able to do so. This finding was consistent with the findings of a qualitative study conducted in two rural medical districts in Burkina Faso.[24]

A deficient referral mechanism was reported as a contributing factor in turning the tide in favor of delivery at private hospitals over the zero expense delivery facilities provided at government centres. The current study highlighted that there was a lack of proper backup for referred cases in government facilities and that this forced patients to avail services from private facilities. Inadequacy of referral services was also reported by Griffiths P et al., and Ram F et al., as a perceived barrier to utilization of health facilities.[19,25] A proper mechanism to classify high-risk cases during antenatal period and thereby counselling them to go directly to higher facilities can help in decreasing this problem. Prior liaising between lower and higher level facilities can help decrease the patients’ apprehensions regarding the referral process.

This study highlighted the barriers to utilization of freely available Maternal and Child Health care (MCH) services at government health facilities. It also brought out the practical experiences of the community health volunteers and explained the determinants of their inability to facilitate delivery at government hospitals. Since this study included only ASHAs of a particular PHC, the results may not be generalized to the entire country. Every PHC should be able to delineate the major causes of underutilization at their local level, as these factors are likely to be different. In addition, ASHA workers’ perceptions cannot be considered an absolute proxy for clients’ perceptions but they are likely to be broadly representative of their views since these volunteers are from the community itself.

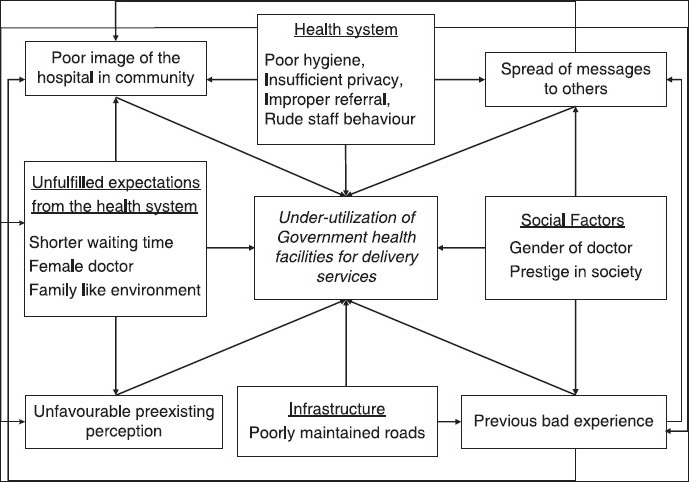

It can postulated that when the institutional delivery rate in an area becomes very high, the extra manpower and facilities that are needed to cater to this increased rate comes in the form of private hospitals. These private services are most often availed by people who are able to pay and who are not restrained by access issues. But a significant proportion of the community who are not rich, still prefer to avail private services due to the several reasons discussed above. They may find it difficult to recover from the huge costs incurred in the process. It is to this portion of the community that the government health facilities should be made more accessible and acceptable so that money does not become an issue for accessing quality care, that is, equity in essence. The factors delineated in this study can be conformed into a framework that brings out the interrelated nature of the components that affect utilisation [Figure 1]. It is recommended that every government facility should display a minimum quality of care. All the lacking facilities should be upgraded, ambulance services should be made accessible in a timely manner, and all staff should be trained to be empathetic towards patients. The referral chain should be strengthened to appropriately deal with referred cases. Public grievance and redressal system should be established in every government health facility that will make the system more accountable and responsive to the needs of the people.

Figure 1.

Determinants of non-utilisation of public health facilities for free delivery services

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Millennium development goals - India country report. New Delhi: 2011. [Accessed May 4, 2014]. Central Statistical Organization, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India. http://www.in.undp.org/content/india/en/home/library/mdg/mdg_india_country_report_2011.html . [Google Scholar]

- 2.New Delhi: Office of Registrar General, India; 2011. Jun, [Accessed May 4, 2014]. Special bulletin on maternal mortality in India 2007-09. http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Bulletins/Final-MMR%20Bulletin-2007-09_070711.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geneva: 2012. [Accessed May 4, 2014]. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank estimates. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2010. https://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2012/Trends_in_maternal_mortality_A4-1.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.New Delhi: Office of Registrar General of India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India; 2010. [Accessed May 4, 2014]. Statistical Report, Sample Registration System. http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/srs/Contents_2010.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 5.About ASHA-National Health Mission. [Accessed May 4, 2014]. http://nrhm.gov.in/communitisation/asha/aboutasha.html .

- 6.New Delhi: 2012. [Accessed May 4, 2014]. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Sixth common review mission report of the National Rural Health Mission. http://nhsrcindia.org/pdf_files/resources_thematic/Health_Sector_Overview/NHSRC_Contribution/Final6thCRM_Book_NRHM.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidelines for Janani-Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK) New Delhi: 2011. [Accessed May 24, 2014]. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. http://nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/jssk/guidelines/guidelines_for_jssk.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, James SL, Hogan MC, Gakidou E. India's Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: An impact evaluation. Lancet. 2010 Jun 5;375(9730):2009–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delivery Hut Scheme. Chandigarh: 2008. [Accessed May 4, 2014]. Department of Health, Government of Haryana. http://haryana.gov.in/DELIVERY%20HUT%20SCHEME.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.I. Mumbai: IIPS; [Accessed May 4, 2014]. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. 2007. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06: India. http://www.iipsindia.org/publications.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mumbai: IIPS; [Accessed May 4, 2014]. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), 2010. District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3), 2007-08: India. http://www.iipsindia.org/publications.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiang C, Labeeb SA, Higuchi M, Mohamed AG, Aoyama A. Barriers to the use of basic health services among women in rural southern Egypt (Upper Egypt) Nagoya J Med Sci. 2013 Aug;75:225–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silal SP, Penn-Kekana L, Harris B, Birch S, McIntyre D. Exploring inequalities in access to and use of maternal health services in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:120. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortaleza, Brazil: 64th WMA General Assembly; 2013. Oct, [Accessed May 4, 2014]. WMA Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kant S, Misra P, Gupta S, Goswami K, Krishnan A, Nongkynrih B, et al. Cohort Profile: The Ballabgarh Health and Demographic Surveillance System (CRHSP-AIIMS) Int J Epidemiol. 2013 Apr 25;:1–11. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mishra A. The role of the Accredited Social Health Activists in effective health care delivery: Evidence from a study in South Orissa. BMC Proc. 2012 Jan 16;6(Suppl 1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deepthi s, Varma M.E. Khan and Avishek hazra. Increasing institutional delivery and Access to emergency obstetric care Services in rural Uttar Pradesh. [Accessed May 4, 2014]. http://medind.nic.in/jah/t10/s1/jaht10s1p23.pdf .

- 18.Singh MK, Singh J, Ahmad N, Kumari R, Khanna A. Factors Influencing Utilization of ASHA Services under NRHM in Relation to Maternal Health in Rural Lucknow. Indian J Community Med Off Publ Indian Assoc Prev Soc Med. 2010 Jul;35:414–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.69272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffiths P, Stephenson R. Understanding users’ perspectives of barriers to maternal health care use in Maharashtra, India. J Biosoc Sci. 2001 Jul;33:339–59. doi: 10.1017/s002193200100339x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephenson R, Tsui AO. Contextual influences on reproductive health service use in Uttar Pradesh, India. Stud Fam Plann. 2002 Dec;33:309–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatia Jagdish C, John Cleland. Determinants of maternal care in a region of India. [Accessed May 4, 2014]. https://digitalcollections.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/41182/2/Bhati1_1.pdf .

- 22.Pandey N. Perceived Barriers to Utilization of Maternal Health and Child Health Services: Qualitative Insights from Rural Uttar Pradesh, India. 2010. [Accessed May 4, 2014]. http://paa2011.princeton.edu/papers/111751 .

- 23.Kesterton AJ, Cleland J, Sloggett A, Ronsmans C. Institutional delivery in rural India: The relative importance of accessibility and economic status. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Some TD, Sombie I, Meda N. Women's perceptions of homebirths in two rural medical districts in Burkina Faso: A qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2011;8:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ram F, Singh A. Is antenatal care effective in improving maternal health in rural uttar pradesh? Evidence from a district level household survey. J Biosoc Sci. 2006 Jul 38;:433–48. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005026453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]