41.1 Introduction

The inherited retinal dystrophies, including retinitis pigmentosa, Leber congenital amaurosis, cone-rod dystrophy, and others, are a remarkably heterogeneous group of blinding disorders displaying both genetic and phenotypic diversity. They encompass a spectrum of diseases all resulting in photoreceptor loss and eventual blindness, but differ in age of onset, severity, cone- or rod-predominance, and associated findings. Some forms of disease are syndromic while other forms are retina-specific. Over 150 different genes have been implicated to date in all inherited retinal dystrophies, and retinitis pigmentosa alone is caused by over 40 genes, many displaying allelic heterogeneity, and some demonstrating both dominant and recessive modes of inheritance (RetNet; http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/retnet/).

Certain genetic causes of retinal degeneration appear particularly prone to variable expressivity. For example, many instances of extreme phenotypic variability have been reported for mutations in RPGR (retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator), which causes over 70% of X-linked RP in addition to cone and cone-rod dystrophy and atrophic macular dystrophy (Ayyagari et al. 2002; Demirci et al. 2002; Yang et al. 2002). RPGR localizes to the connecting cilium in photoreceptors and is thought to play a role in protein transport (Roepman et al. 2000; Hong et al. 2003; Khanna et al. 2005). Until recently, the “GTPase regulator” function of RPGR was largely speculative, but recent evidence shows that RPGR interacts with the GTPase RAB8A and that disease-causing mutations in RPGR disrupt this interaction (Murga-Zamalloa et al. 2010). X-linked RP demonstrates marked variable expressivity among both affected males, who demonstrate a wide range of severity, and female carriers, who may or may not have clinical symptoms (Souied et al. 1997; Grover et al. 2000). In addition, there have been multiple reports of diagnoses of both X-linked retinitis pigmentosa and cone-rod dystrophy within the same family (Keith et al. 1991; Walia et al. 2008).

Some of the observed phenotypic diversity is undoubtedly due to considerable allelic heterogeneity: over 100 different RPGR mutations have been found to date in families with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XlRP) (Human Gene Mutation Database; http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/). However, the same mutation often results in varying degrees of clinical severity, and sometimes different diagnoses, both across families and within families. This variable expressivity suggests the presence of either genetic or environmental Modifiers, or both, playing a substantial role in disease expression.

This study aimed to categorize the clinical diversity in a cohort of 98 affected males from 56 families with RPGR mutations, and to test candidate Modifier genes for association with disease severity. Ninety-eight affected males with 44 different RPGR mutations were included. Candidate Modifier genes were chosen according to the following criteria: (1) the protein is known to interact with RPGR, (2) the protein has polymorphic amino acid substitutions, and (3) the gene contains known retinal disease-causing mutations. Based on these criteria, coding SNPs in RPGR-interacting protein 1 (RPGRIP1) (Boylan and Wright 2000; Dryja et al. 2001), RPGRIP1-like (RPGRIP1L) (Arts et al. 2007; Delous et al. 2007; Khanna et al. 2009), centrosomal protein 290 kDa (CEP290) (den Hollander et al. 2006; Sayer et al. 2006; Baala et al. 2007), and IQ motif containing B1 (IQCB1 aka nephrocystin- 5) (Otto et al. 2005) were chosen for analysis. This study describes and categorizes phenotypic severity in a cohort of 98 males with RPGR mutations and reports two SNPs in candidate Modifier genes associated with disease severity.

41.2 Materials and Methods

41.2.1 Patients and Clinical Assessment

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research was approved by the Committees for Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Ninety-eight affected males from 56 families were enrolled. Clinical assessment included manifest refraction and best-corrected visual acuity, Humphrey visual fields, frequency domain optical coherence tomography, dark-adapted threshold, full-field electroretinogram, and multifocal electroretinogram.

Fifty-four of the 98 affected males had 3 or more visits at least 1 year apart. For these individuals, log cone 31 Hz flicker ERG amplitude was plotted as a function of patient age and linear regression analysis was used to determine the predicted amplitude at age 18 (Berson et al. 1985; Birch et al. 1999; Berson 2007). The 54 patients with multiple visits were characterized as grade 1 (mild), grade 2 (moderate), or grade 3 (severe) based on the derived cone 31 Hz flicker ERG amplitude at age 18, supplemented by Humphrey visual fields. Supplementary measures, along with cone ERG amplitude, were also used to characterize the 44 patients with a single visit. Criteria used to categorize patients as grade 1, 2, or 3 are summarized in Table 41.1.

Table 41.1.

Males with XlRP were divided into grades 1, 2, and 3 according to the clinical criteria shown in the table

| Severity | ERG | Visual field |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | ≥ 10 µV 30 Hz flicker in teens (1–5 µV in 30s) | Good central 30° field sensitivity |

| Grade 2 | 1–5 µV 30 Hz flicker in teens | Marked central field constriction; some sensitivity beyond 20° |

| Grade 3 | <1 µV 30 Hz flicker in teens/20s | Marked central field constriction |

41.2.2 Genotyping Candidate Modifier Loci

Blood samples were collected in EDTA-coated tubes, and DNA was extracted using the Gentra Puregene blood kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA sequences containing SNPs of interest were amplified from 37.5 ng genomic DNA per reaction with either AmpliTaq Gold 360 (Applied Biosystems) or PyroMark PCR Kit (Qiagen). The PyroMark PCR reactions included two specific primers, one of which contained an M13 tail, and a universal biotinylated M13 primer, as described by Guo and Milewicz (2003). PCR conditions for PyroMark reactions were as follows: 95°C for 15 min, 45 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, followed by extension at 72°C for 10 min. Reactions were run on a PSQ HS 96A Instrument (Qiagen).

41.2.3 Data Analysis

Family-based association testing was performed using the DFAM procedure in PLINK (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/) (Purcell et al. 2007). As this analysis requires a dichotomous phenotype, patients with grade 1 or 3 RP were compared, while patients with grade 2 RP were excluded.

41.3 Results

41.3.1 Phenotypic Heterogeneity Between and Within Families

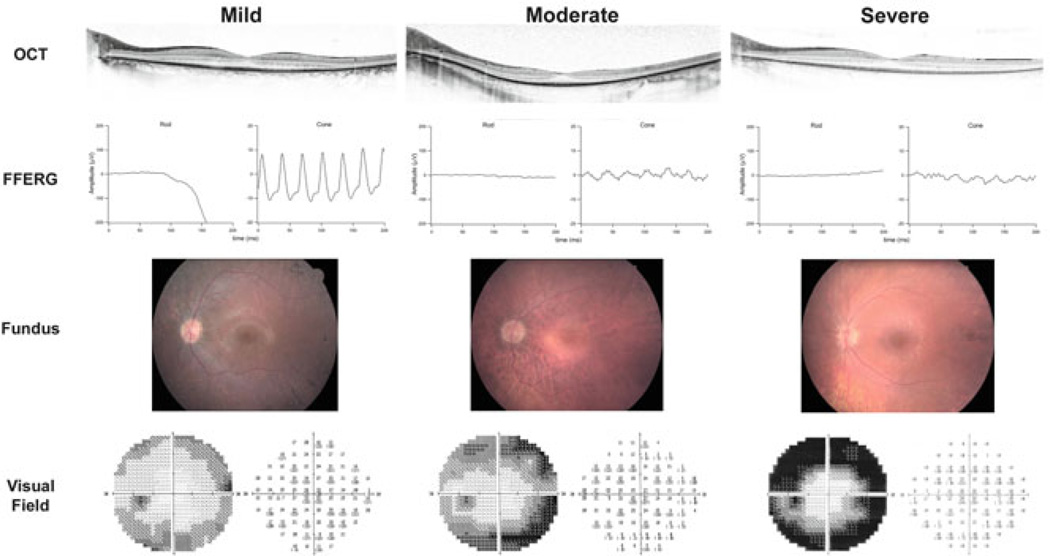

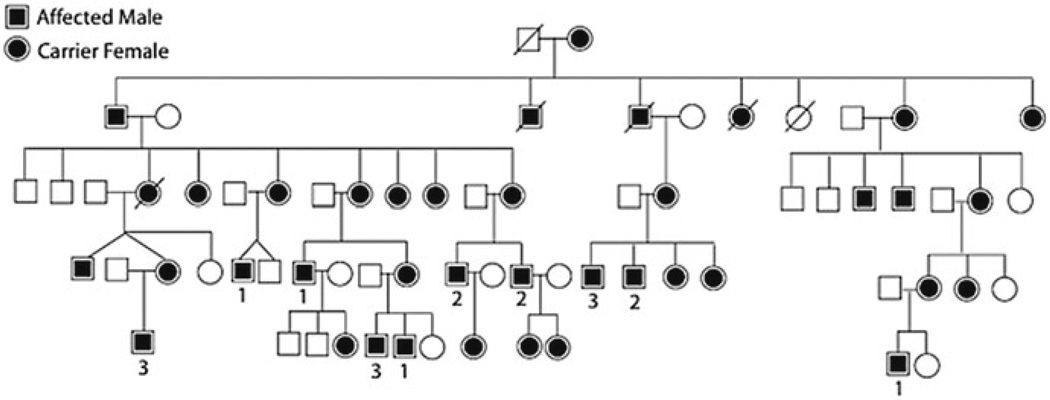

Ninety-eight affected males from 56 families with mutations in RPGR were ascertained and categorized as grade 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe) according to the clinical criteria in Table 41.1. The cohort included 21 grade 1, 34 grade 2, and 43 grade 3 affected males. RPGR mutations have historically been fully penetrant in the hemizygous state, consistent with the absence of known nonpenetrance in our cohort. Representative fund us photos, ERGs, and visual fields from each category are shown in Fig. 41.1. Most pedigrees were too small to assess intrafamilial phenotypic variability. However, Fig. 41.2 shows one of the largest pedigrees in the study, which demonstrated marked phenotypic heterogeneity.

Fig. 41.1.

Shown are OCT scans, ffERGs, fundus photos, and visual fields from representative mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), and severe (grade 3) males from families enrolled in this study

Fig. 41.2.

A large pedigree with XlRP is shown with phenotypic variability. 1 = grade1, 2 = grade 2, 3 = grade 3

41.3.2 Modifier SNPs

Coding SNPs with MAF ≥ 2% in RPGRIP1, RPGRIP1L, CEP290, and IQCB1 (a.k.a. NPHP5) were sequenced in the cohort of 98 affected males and in 99 available family members. Family-based association testing was performed using the DFAM test in PLINK (Purcell et al. 2007) comparing individuals with grade 1 (mild) and grade 3 (severe) RP. Two coding SNPs showed significant association: rs1141528 (I393N) in IQCB1 and rs2302677 (R744Q) in RPGRIP1L (Table 41.2). In IQCB1, the minor allele (as paragine) at position 393 was associated with more severe disease (p = 0.044). In RPGRIP1L, the common allele (arginine) at position 744 was associated with more severe disease (p = 0.049).

Table 41.2.

The results of the family-based association testing are shown

| Gene | SNP | p value |

|---|---|---|

| RPGRIP1 | P96Q | 0.622 |

| K192E | 0.367 | |

| A547S | 0.684 | |

| E1033Q | 0.294 | |

| RPGRIP1L | A229T | 0.564 |

| R744Q | 0.049 | |

| G1025S | 0.523 | |

| D1264N | 0.920 | |

| CEP290 | K838E | 0.698 |

| L906W | NA | |

| IQCB1 | I393N | 0.044 |

| C434Y | 0.977 |

Coding SNPs that were sequenced in the 98 affected males are shown with their respective p values calculated using the DFAM procedure in PLINK. p values <0.05 are shown in bold

41.4 Discussion

This study described and categorized the clinical diversity in a cohort of 98 affected males from 56 families with RPGR mutations, and demonstrated association in the cohort between severe disease and coding SNPs in two proteins known to interact with RPGR. In IQCB1, residue 393 lies in one of two calmodulin-binding domains, and interaction between IQCB1 and calmodulin has been previously demonstrated (Otto et al. 2005). Studies have shown that calmodulin is an important modulator of the cGMP-gated cation channel in rods (Chen et al. 1994). IQCB1 I393N is a predicted benign variant by PolyPhen-2 (Adzhubei et al. 2010). In RPGRIP1L, residue 744 lies in the linker region between two C2 domains and is predicted to be probably damaging by PolyPhen-2 (Delous et al. 2007; Adzhubei et al. 2010).

There have been three prior reports of coding SNPs in cilia proteins acting as genetic Modifiers in ciliopathies. In a group of 602 patients with various syndromic ciliopathies caused by mutations in different genes, the threonine allele at the A229T coding SNP in RPGRIP1L was associated with increased frequency of retinopathy as part of the syndromic phenotype (Khanna et al. 2009). Furthermore, the authors demonstrated that the associated protein variant disrupted binding of RPGRIP1L to RPGR. Of note, the A229T SNP was sequenced in our cohort, but no association with disease severity was found. A similar modifying effect was found in nephronophthisis, a hereditary fibrocystic renal disease with variable retinopathy most commonly caused by mutations in NPHP1. In a group of 306 patients with nephronophthisis, the minor allele at a coding SNP in AHI1, a cilia protein that interacts with NPHP1, was associated with increased frequency of retinopathy (Louie et al. 2010). The same variant in AHI1 was also found to be associated with neurologic symptoms in nephronophthisis (Tory et al. 2007). As there are no reports of direct interaction between AHI1 and RPGR, SNPs in AHI1 were not included in our study.

Genetic Modifiers achieve a remarkable genetic phenomenon: the generation of a complex genetic trait superimposed on an underlying Mendelian trait. Discovery of Modifier genes leads to new investigations in the biology of disease and in potential therapeutics. In addition, genotyping Modifier loci in patients may have prognostic utility. This study and future studies of retinitis pigmentosa Modifier genes help to define the total genetic contribution to disease and to understand the complexity of phenotypic variation in this otherwise Mendelian disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Hixson for the monsomic cell line DNA, Hemaxi Patel for assistance in visual function testing, and Martin Klein for assistance in creating Fig. 41.1. This work was funded by the Foundation Fighting Blindness and NEI/NIH grant EY007142 to SPD.

Contributor Information

Abigail T. Fahim, Human Genetics Center, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, USA

Sara J. Bowne, Human Genetics Center, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, USA

Lori S. Sullivan, Human Genetics Center, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, USA

Kaylie D. Webb, Retina Foundation of the Southwest, Dallas, TX 75231, USA

Jessica T. Williams, Human Genetics Center, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, USA

Dianna K. Wheaton, Retina Foundation of the Southwest, Dallas, TX 75231, USA Department of Ophthalmology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75231, USA.

David G. Birch, Retina Foundation of the Southwest, Dallas, TX 75231, USA Department of Ophthalmology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75231, USA.

Stephen P. Daiger, Email: stephen.p.daiger@uth.tmc.edu, Human Genetics Center, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

References

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts HH, Doherty D, van Beersum SE, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the basal body protein RPGRIP1L, a nephrocystin-4 interactor, cause Joubert syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:882–888. doi: 10.1038/ng2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyagari R, Demirci FY, Liu J, et al. X-linked recessive atrophic macular degeneration from RPGR mutation. Genomics. 2002;80:166–171. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baala L, Audollent S, Martinovic J, et al. Pleiotropic effects of CEP290 (NPHP6) mutations extend to Meckel syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:170–179. doi: 10.1086/519494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson EL. Long-term visual prognoses in patients with retinitis pigmentosa: the Ludwig von Sallmann lecture. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson EL, Sandberg MA, Rosner B, et al. Natural course of retinitis pigmentosa over a three-year interval. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99:240–251. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(85)90351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch DG, Anderson JL, Fish GE. Yearly rates of rod and cone functional loss in retinitis pigmentosa and cone-rod dystrophy. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:258–268. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan JP, Wright AF. Identification of a novel protein interacting with RPGR. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2085–2093. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.14.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TY, Illing M, Molday LL, et al. Subunit 2 (or beta) of retinal rod cGMP-gated cation channel is a component of the 240-kDa channel-associated protein and mediates Ca(2+)-calmodulin modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11757–11761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delous M, Baala L, Salomon R, et al. The ciliary gene RPGRIP1L is mutated in cerebellooculo- renal syndrome (Joubert syndrome type B) and Meckel syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:875–881. doi: 10.1038/ng2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci FY, Rigatti BW, Wen G, et al. X-linked cone-rod dystrophy (locus COD1): identification of mutations in RPGR exon ORF15. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1049–1053. doi: 10.1086/339620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hollander AI, Koenekoop RK, Yzer S, et al. Mutations in the CEP290 (NPHP6) gene are a frequent cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:556–561. doi: 10.1086/507318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryja TP, Adams SM, Grimsby JL, et al. Null RPGRIP1 alleles in patients with Leber congenital amaurosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1295–1298. doi: 10.1086/320113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S, Fishman GA, Anderson RJ, et al. A longitudinal study of visual function in carriers of X-linked recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:386–396. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo DC, Milewicz DM. Methodology for using a universal primer to label amplified DNA segments for molecular analysis. Biotechnol Lett. 2003;25:2079–2083. doi: 10.1023/b:bile.0000007075.24434.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong DH, Pawlyk B, Sokolov M, et al. RPGR isoforms in photoreceptor connecting cilia and the transitional zone of motile cilia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2413–2421. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith CG, Denton MJ, Chen JD. Clinical variability in a family with X-linked retinal dystrophy and the locus at the RP3 site. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet. 1991;12:91–98. doi: 10.3109/13816819109023680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna H, Hurd TW, Lillo C, et al. RPGR-ORF15, which is mutated in retinitis pigmentosa, associates with SMC1, SMC3, and microtubule transport proteins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33580–33587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505827200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna H, Davis EE, Murga-Zamalloa CA, et al. A common allele in RPGRIP1L is a modifier of retinal degeneration in ciliopathies. Nat Genet. 2009;41:739–745. doi: 10.1038/ng.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie CM, Caridi G, Lopes VS, et al. AHI1 is required for photoreceptor outer segment development and is a modifier for retinal degeneration in nephronophthisis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:175–180. doi: 10.1038/ng.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murga-Zamalloa CA, Atkins SJ, Peranen J, et al. Interaction of retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) with RAB8A GTPase: implications for cilia dysfunction and photoreceptor degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3591–3598. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto EA, Loeys B, Khanna H, et al. Nephrocystin-5, a ciliary IQ domain protein, is mutated in Senior-Loken syndrome and interacts with RPGR and calmodulin. Nat Genet. 2005;37:282–288. doi: 10.1038/ng1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roepman R, Bernoud-Hubac N, Schick DE, et al. The retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) interacts with novel transport-like proteins in the outer segments of rod photoreceptors. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2095–2105. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.14.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer JA, Otto EA, O’Toole JF, et al. The centrosomal protein nephrocystin-6 is mutated in Joubert syndrome and activates transcription factor ATF4. Nat Genet. 2006;38:674–681. doi: 10.1038/ng1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souied E, Segues B, Ghazi I, et al. Severe manifestations in carrier females in X linked retinitis pigmentosa. J Med Genet. 1997;34:793–797. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.10.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tory K, Lacoste T, Burglen L, et al. High NPHP1 and NPHP6 mutation rate in patients with Joubert syndrome and nephronophthisis: potential epistatic effect of NPHP6 and AHI1 mutations in patients with NPHP1 mutations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1566–1575. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006101164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walia S, Fishman GA, Swaroop A, et al. Discordant phenotypes in fraternal twins having an identical mutation in exon ORF15 of the RPGR gene. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:379–384. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2007.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Peachey NS, Moshfeghi DM, et al. Mutations in the RPGR gene cause X-linked cone dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:605–611. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]