Abstract

Background

Diagnosing coeliac disease (CD) can be challenging, despite highly specific autoantibodies and typical mucosal changes in the small intestine. The T-cell response to gluten is a hallmark of the disease that has been hitherto unexploited in clinical work-up.

Objectives

We aimed to develop a new method that directly visualizes and characterizes gluten-reactive CD4+ T cells in blood, independently of gluten challenge, and to explore its diagnostic potential.

Methods

We performed bead-enrichment of DQ2.5-glia-α1a and DQ2.5-glia-α2 tetramer+ cells in the blood of control individuals, treated (TCD) and untreated patients (UCD). We visualized these cells by flow cytometry, sorted them and cloned them. We assessed their specificity by antigen stimulation and re-staining with tetramers.

Results

We detected significantly more gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ effector memory T cells (TEM) in UCD and TCD patients, compared to controls. Significantly more gliadin-tetramer+ TEM in the CD patients than in controls expressed the gut-homing marker integrin-β7.

Conclusion

Quantification of gut-homing, gluten-specific TEM in peripheral blood, visualized with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) -tetramers, may be used to distinguish CD patients from healthy individuals. Easy access to gluten-reactive blood T cells from diseased and healthy individuals may lead to new insights on the disease-driving CD4+ T cells in CD.

Keywords: Blood test, celiac disease, diagnostic marker, diagnostics, gliadin, gluten, gluten reactivity, human leukocyte antigen, histology, immunology, T cells

Introduction

Coeliac disease (CD) is an inflammatory condition of the small intestine caused by intolerance to proline- and glutamine-rich cereal gluten proteins.1 In wheat, gluten consists of several hundred distinct but similar proteins that can be classified into gliadins and glutenins.2 CD is often detected after demonstration of autoantibodies specific for the enzyme transglutaminase 2 (TG2).3 Children can be diagnosed with CD if the TG2 antibody titer is high, added by further laboratory tests4; however, in adults, duodenal biopsy and detection of typical histological changes remains a diagnostic premise.5

Despite clear diagnostic criteria,5 diagnosing CD can be difficult and false negative tests are a problem. Autoantibodies can be present in tissues only, but not detectable in blood.6 In other instances, the diagnosis cannot be made because of minor or no changes in the duodenal mucosa, despite elevated TG2 antibodies.7 Some of these individuals will develop further histological changes and overt disease that can only be diagnosed if gastroduodenoscopy is repeated.7

The T-cell response to gluten is essential in the immunopathogenesis of CD.8 CD4+ T cells that recognize distinct gluten epitopes in the context of the disease-associated human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules DQ2.5, DQ8 and DQ2.2 can be detected in the gut mucosa of CD patients, but not of healthy controls.9,10 For HLA-DQ2.5, which is expressed by the great majority of CD patients, two epitopes of α-gliadin (DQ2.5-glia-α1a and DQ2.5-glia-α2) are among the immunodominant epitopes.11

Monitoring of the T-cell response to gluten has not been applied in the diagnostic work-up of CD patients. The clinical value of detecting gluten-reactive T cells in the gut of CD patients9,12 is limited by the need of a gastroduodenoscopy. CD4+ T cells recognizing CD-relevant epitopes can also be detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) using enzyme-linked immunospot- or tetramer-based assays; however, this has so far only been possible in treated CD patients (TCD) after a 3-day oral gluten-challenge.13,14 Notably, gluten-specific T cells are not detectable above background in healthy controls, untreated CD patients (UCD) or TCD without gluten-challenge.

In the current study, we did bead-enrichment of gliadin-tetramer+ cells to increase the sensitivity for detection of gluten-reactive T cells. By doing so, we were able to track CD4+ T cells reactive to DQ2.5-glia-α1a and DQ2.5-glia-α2 of three T-cell subsets: naïve (TN), central memory (TCM) and effector memory (TEM) cells. TN are preimmune cells that can differentiate into memory T cells, if encountering a corresponding antigen. Memory T cells are categorized by homing markers and cytokine production into TEM that act at the site of inflammation, and TCM that can migrate to lymphoid tissues.15 We found significantly more gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ TEM in the blood of CD patients than controls. These cells were gut-homing and were found in larger numbers in CD patients with severe duodenal changes, compared to CD patients with normal mucosa. The protocol gives easy access to gluten-reactive T cells from affected and healthy individuals. Further studies on these cells may extend our understanding of one of the key players in CD pathogenesis. Our findings demonstrated that this T-cell based, minimally invasive, ex-vivo assay has potential in the diagnosis of CD.

Methods

Subjects and ethical aspects

As detailed in Table 1, 20 UCD, 18 TCD and 16 control individuals acceded to the study. They were genomically HLA-typed and we report only the commonly CD-associated HLA-types (DQ2.5 = DQA1*05 and DQB1*02; DQ2.2 = DQA1*02 : 01 and DQB1*02; and DQ8 = DQA1*03 and DQB1*03 : 02). We obtained blood from 14 DQ2.5+ controls through the blood bank at Oslo University Hospital, Norway. These individuals were anonymous. We have no data on their diet, biomarkers or clinical state; but diagnosed CD is an exclusion criterion for blood donation. All other participants were patients who, after giving informed written consent, donated additional blood for research purposes in conjunction to duodenal biopsies and routine clinical follow-up at the Oslo University Hospital. Patients were diagnosed according to statements from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA).5 Each TCD had been on a gluten-free diet (GFD) for 3 months or more. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee (S-97201).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Participant | Categorya | HLA-type | Anti-TG2 < 5 U/mLb | Marsh- score | EM/N- ratio α1a | EM/N- ratio α2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| P2 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 6.8d | |

| P3 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| P4 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.1d | |

| P5 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.1 | ND |

| P6 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| P7 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| P8 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| P9 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| P10 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| P11 | Control | DQ2.5/DQ8 | <1.0 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| P12 | Control | DQ2.5/DQ8 | <1.0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| P13 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.3d | |

| P14 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.2d | |

| P15 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.4d | |

| P16 | Control | DQ2.5 | ND | ND | 0.4d | |

| P17 | UCD | DQ2.5/DQ8 | 10.6 | 3B | 21.0 | 4.1 |

| P18 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 16.3 | 3B | 14.5 | 4.9 |

| P19 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 10.0 | 3A | 6.8 | 1.0 |

| P20 | UCD | DQ2.5/DQ8 | >120 | 3B | 13.2 | 4.6 |

| P21 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 12.5 | 3A/B | 18.8 | 1.7 |

| P22 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 48.0 | 3A | 55.0 | 40.0 |

| P23 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 67.0 | 3B/C | 7.3 | 4.7 |

| P24 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 3.3 | 3A | ND | 7.3 |

| P25 | UCD | DQ2.5 | ND | 3A | ND | 12.8 |

| P26 | UCD | DQ2.5 | ND | 2 | 22.6 | 49.5 |

| P27 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 16.4 | 3A | 2.3 | 1.7 |

| P28 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 5.4 | 3B-Cc | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| P29 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 3.8 | 3C | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| P30 | UCD | DQ2.5/DQ8 | 4.8 | 3B | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| P31 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 11.0 | 3B | 13.7 | 12.2 |

| P32 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 35.7 | 2 | 33.0 | 11.7 |

| P33 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 5.7 | 3A | 28.5 | 16.3 |

| P34 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 3.1 | 3B | 7.5 | 8.8 |

| P35 | UCD | DQ2.5 | 2.2 | 3A | 7.6 | 14.4 |

| P36 | TCD | DQ2.5 | 3.3 | 3B | 1.5 | 3.0 |

| P37 | TCD | DQ2.5 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| P38 | TCD | DQ2.5 | 1.1 | 0 | 2.0 | 0.8 |

| P39 | TCD | DQ2.5 | 2.1 | 2 | 15.9 | 19.3 |

| P40 | TCD | DQ2.5 | ND | 3A | 52.0 | 22.8 |

| P41 | TCD | DQ2.5 | <1.0 | ND | 5.3 | 4.0 |

| P42 | TCD | DQ2.5 | <1.0 | 2 | 2.1 | 10.7 |

| P43 | TCD | DQ2.5/DQ8 | <1.0 | 3A | 9.8 | 36.3 |

| P44 | TCD | DQ2.5 | <1.0 | 0 | 9.0 | 4.7 |

| P45 | TCD | DQ2.5 | <1.0 | 0 | 9.5 | 0.8 |

| P46 | TCD | DQ2.5 | ND | 2 | 1.2 | 6.5 |

| P47 | TCD | DQ2.5 | <1.0 | 0 | 2.0 | 0.8 |

| P48 | TCD | DQ2.5 | ND | 2 | 1.9 | 2.6 |

| P49 | TCD | DQ2.5 | <1.0 | 0 | 1.7d | |

| P50 | TCD | DQ2.5 | 1.4 | ND | 0.3d | |

| P51 | TCD | DQ2.5 | <1.0 | 0 | 9.9d | |

| P52 | TCD | DQ2.5 | <1.0 | 2 | 2.8d | |

| P53 | TCD | DQ8 | 1.1 | 3A | 0.0 | 0.4 |

| P54 | UCD | DQ2.2 | <1.0 | 3A/B | 0.0 | 0.1 |

Patients P1-P10 and P13-P16 were anonymous blood bank donors.

UCD were usually referred to gastroduodenoscopy with IgA anti-TG2 above cut-off. These values refer to the repeated sample at time of endoscopy.

The mucosal changes were only asserted in the bulbus duodeni, in this participant.

The gliadin-tetramer-staining was combined on one fluorochrome.

EM/N-ratio: the ratio between gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ effector memory and naïve T cells; HLA: human leukocyte antigen; IgA: immunoglobulin A; ND: not done; P: participant; TCD: treated coeliac disease; UCD: untreated coeliac disease.

Tetramers

Soluble, biotinylated DQ2.5 (DQA1*05 : 01, DQB1*02 : 01) molecules covalently linked with the gluten-derived T-cell epitopes DQ2.5-glia-α1 a (QLQPFPQPELPY, with underlined 9mer core sequence) or DQ2.5-glia-α2 (PQPELPYPQPE) were multimerized on phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled streptavidin (Invitrogen) or allophycocyanin (APC)-labeled streptavidin (ProZyme).16 Cells were incubated with the tetramers (300 µl; 10 µg/ml each) at room temperature, for 40 minutes.

Cell enrichment

We obtained 50–100 ml of citrated full blood, or 60 ml of citrated buffy coat produced from 450 ml of full blood, from each participant. We isolated the PBMC by density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep; Axis-Shield), and further handled in a buffer containing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 1% human serum.

We followed an established protocol for enrichment of tetramer-positive cells.17 Briefly, PBMC were counted and incubated with FcR blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec) before the PE- and APC-conjugated tetramers were added. The cells were washed and a small fraction removed for later staining as a ‘pre-enriched sample’ before we added the anti-PE- and anti-APC microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). We then washed the cells, re-counted them and passed them over a magnetized column (MS or LS column, Miltenyi Biotec). We collected the cells that did not bind the column as ‘depleted cells’.

Flow cytometry

The enriched cells were eluted and all samples were stained 20 minutes on ice at a volume of 25 µl. The following antibodies were used: CLA-FITC, Integrin-β7-PE, CD62L-PerCP/Cy5.5, CD14-Pacific blue, CD19-Pacific blue, CD56-Pacific blue, CD11c-V450, CD4-APC-H7 (all from BD Biosciences); as well as CD45RA-PE-Cy7 and CD3-eFluor605 (both from eBioscience). We washed and analyzed the cells on a LSR II (BD Biosciences) or sorted on a FACS Aria I cell sorter (BD Biosciences). The entire enriched samples were run through, in order to enumerate all tetramer-positive cells.

Cells binding the DQ2.5-glia-α1a- or the DQ2.5-glia-α2-tetramer were identified as relevant if they were: CD3+, CD11c-, CD14-, CD19-, CD56- and CD4+. Relevant gliadin-tetramer+ cells were sub-divided into and sorted as CD45RA+/CD62L+ cells (TN), CD45RA-/CD62L- cells (TEM) and CD45RA-/CD62L+ cells (TCM) (see Figure 1(a) and Figure 1(b)).18 Integrin-β7 staining was performed in four controls and four TCD; and cutaneous leucocyte-associated antigen (CLA) staining in one TCD (see Figure 4).

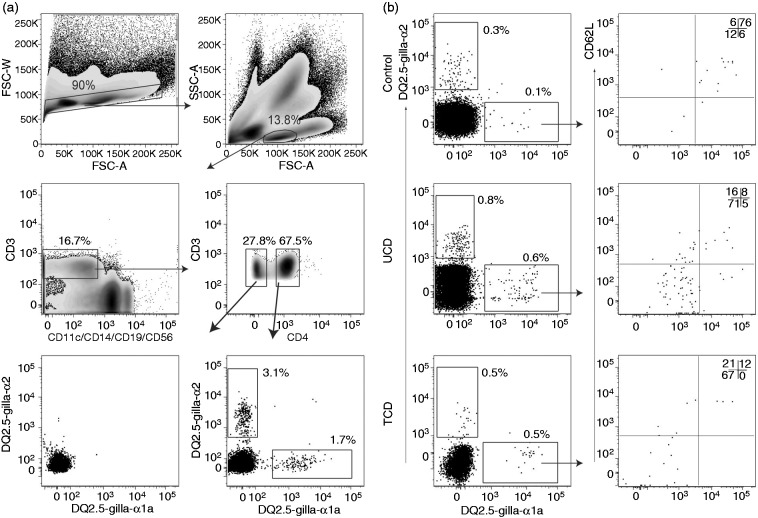

Figure 1.

Gating strategy. Flow cytometric density plots and dot plots illustrating the gating strategy for relevant gliadin-tetramer+ cells. Percentages of gated cells within each plot are shown. (a) Gating was done on single cells → lymphocytes → CD3+ cells → CD4+ cells. There were few gliadin-tetramer+ cells among CD3+ CD4- cells (lower left plot); whereas there were distinct populations of CD3+ CD4+ gliadin-tetramer+ cells (lower right plot), here shown in a TCD patient. (b) Dot plots in the left panels show CD4+ T cells in bead-enriched samples from a control individual, UCD and TCD patients binding the two different gliadin-tetramers. Tetramer+ CD4+ T cells were subdivided by the results of CD62L- and CD45RA-staining into effector memory (double negative), naïve (double positive) and central memory (CD62L+ and CD45RA-) T cells. FSC-W: Forward scatter width; FSC-A: Forward scatter areal; SSC-A: Side scatter areal; TCD: Treated coeliac disease; UCD: Untreated coeliac disease.

Figure 4.

Gut-homing of T cells. (a) While gliadin-tetramer+ N T cells expressed integrin-β7 at intermediate levels and the CM T cells showed no clear staining, nearly all gliadin-tetramer+ EM T cells in TCD expressed integrin-β7. Gliadin-tetramer positive and negative EM T cells in controls expressed similar amounts of integrin-β7. The DQ2.5-glia-α1a- and DQ2.5-glia-α2-tetramer were combined on one fluorochrome, to increase the number of relevant cells. (b) The percent of integrin-β7 expression on tetramer-positive and tetramer-negative cells in four TCD and four controls. (c) Tetramer+ EM in one tested TCD did not express the skin-homing CLA. Percentages of gated cells within each plot are denoted by numbers. CLA: cutaneous leukocyte-associated antigen; CM: central memory; EM: effector memory; N: naïve; TCD: treated coeliac disease patients.

We calculated the frequencies of gliadin-tetramer+ cells as follows:

The total number of CD4+ T cells was calculated by multiplying the fraction of CD4+ T cells stained in the pre-enriched sample with the total number of counted PBMC. We used FlowJo software (Tree Star) for analysis of flow data.

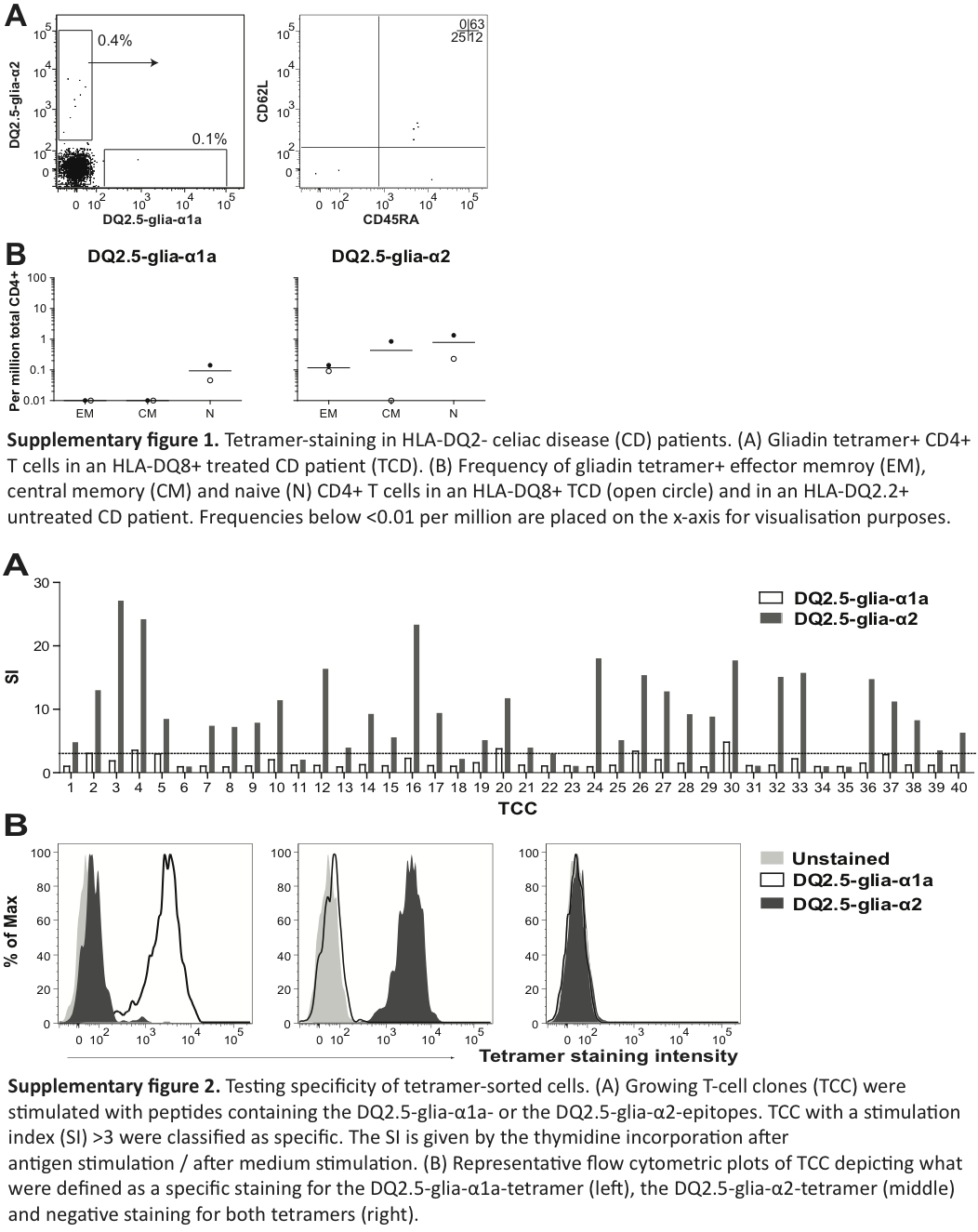

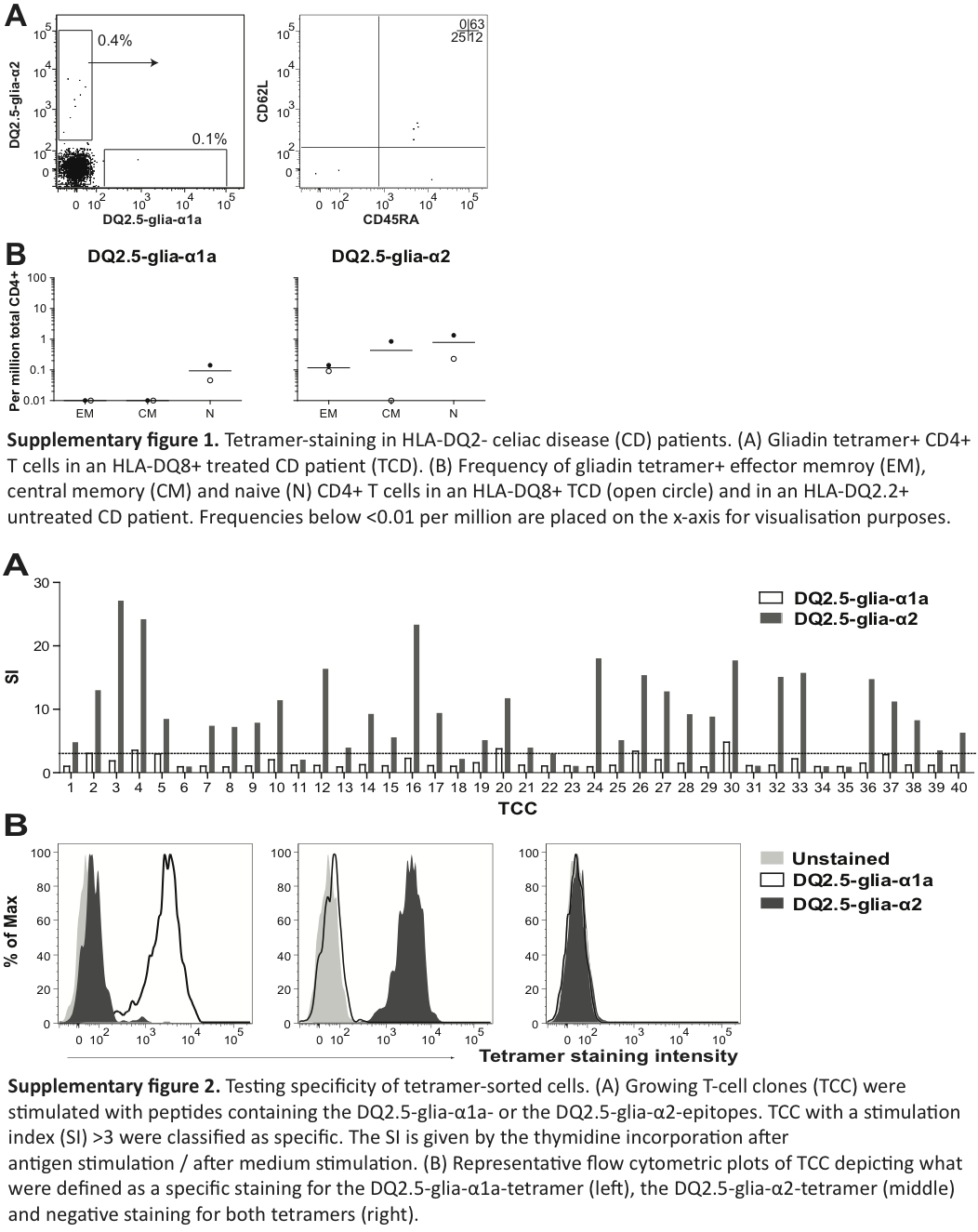

Culturing and screening of sorted cells

The sorted cells were cloned by limited dilution and expanded without antigens, as previously described.19 Growing T-cell clones (TCC) were tested both in a T-cell proliferation assay and by re-staining with gliadin-tetramers. We analyzed the tetramer-stained cells on a FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences) (Supplementary Figure 1). Cells showing a clear shift in staining-intensity with the DQ2.5-glia-α1a–tetramer compared to the DQ2.5-glia-α2-tetramer and the unstained control were identified as specific for the DQ2.5-glia-α1a-peptide, and vice versa.

We used a well-established protocol for antigen-dependent T-cell proliferation.19 Briefly, we used DQ2.5 homozygous Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformed cells (IHW #9023) presenting the DQ2.5-glia-α1a-epitope peptide (QLQPFPQPELPY, underlined 9mer core sequence) or a peptide containing the DQ2.5-glia-α2-epitope (PQPELPYPQPQL) (both from Research Genetics). The final peptide concentration was 10 µM. We assessed T-cell proliferation by thymidine incorporation.19 The TCC that dispalyed a stimulation index (SI) above three, calculated by dividing counts per minute (cpm) after antigen stimulation with cpm after medium stimulation, were identified as peptide-specific.

Statistical analysis

We used the GraphPad Prism 5 software for statistical analysis and the Mann-Whitney U test to calculate statistical significance.

Results

Visualizing gluten-specific T cells in peripheral blood

Motivated by a protocol that can detect rare epitope-specific naïve CD4+ T cells by tetramer-staining and bead-enrichment,17 we aimed to identify CD4+ T cells that are reactive to the two dominant gluten-epitopes, DQ2.5-glia-α1a and DQ2.5-glia-α2, in blood from DQ2.5+ controls, UCD and TCD (Table 1) without oral gluten challenge. We used strict gating for identification of gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ T cells (Figure 1(a)) and subpopulations of these cells (Figure 1(b)).

In all but one control subjects, we identified relatively few gliadin TCM or TEM and a distinct population of gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ TN. In control subject P2, we found a large number of gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ TEM, similar to levels found in UCD patients. We suspected that subject P2 had CD that was undiagnosed; however, as this participant was an anonymous blood donor, we were unable to do any clinical examination. This subject and the other blood bank donors were all included in the group of control individuals. We also observed some gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ T cells in non-HLA-DQ2.5 subjects (Supplementary figures 2(a) and 2(b)), similar to what has been observed with other HLA II tetramers.20

Validating the gluten specificity of tetramer+ T cells

Gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ TN, and in some cases also TEM and TCM from six controls, two UCD and five TCD were sorted, cloned by limiting dilution and cultured in an antigen-independent manner. The success rate of generating TCC from sorted T cells differed substantially between the subjects. On average, we cultured growing TCC from one-fourth of sorted cells (Table 2). Each generated TCC was assayed for proliferative response to the DQ2.5-glia-α1a- and the DQ2.5-glia-α2-epitope. We found that 122/163 TEM, 4/20 TCM and 76/193 TN clones responded to the epitope (with a SI ≥ 3) of the tetramer for which they originally were isolated. Gliadin-tetramer+ TCM and TEM cells from subject P40 were sorted together and 23/30 of these clones were specific in the T-cell assay (Supplementary Figure 2(a)). All TCCs that gave specific responses in T-cell assays had a clear and specific staining with the corresponding tetramer. Five TEM and 30 TN clones showed poor proliferation (SI < 3), despite clear tetramer staining. Twelve of the co-sorted TEM and TCM clones from subject P40 also held this feature.

Table 2.

The specificity of TCC cultured from tetramer-sorted CD4+ T cells

| Participant | Category | Cultured TCC (%) |

Specific/proliferating TCC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM | CM | N | EM | CM | N | ||

| P1 | Control | ND | ND | 27 | ND | ND | 24/30 |

| P2 | Control | ND | ND | 32 | ND | ND | 20/24 |

| P3 | Control | ND | ND | 41 | ND | ND | 30/32 |

| P4 | Control | ND | ND | 31 | ND | ND | 13/13 |

| P8 | Control | 33 | 25 | 62 | 0/4 | 2/6 | 3/29 |

| P11 | Control | 0 | ND | 42 | 0/0 | ND | 2/8 |

| P17 | UCD | 3 | ND | 11 | 4/4 | ND | 1/1 |

| P18 | UCD | 23 | ND | 43 | 70/72 | ND | 8/13 |

| P36 | TCD | 20 | ND | 32 | 7/8 | ND | 3/9 |

| P37 | TCD | 33 | ND | 8 | 1/2 | ND | 2/2 |

| P40 | TCD | 21a | 50 | 35/39a | 0/1 | ||

| P42 | TCD | 16 | 17 | 52 | 7/15 | 0/3 | 0/17 |

| P43 | TCD | 33 | 16 | 18 | 38/58 | 2/11 | 0/16 |

Table 2 shows the percentage of sorted EM, CM and N type T cells successfully expanded by the antigen-independent cloning and the number of specific TCC, as defined by specific re-staining, of the total number of growing TCC. In this table, CD4+ T cells binding the DQ2.5-glia-α1a- or the DQ2.5-glia-α2-tetramer are merged.

TEM and TCM were sorted into one tube.

CM: Central memory; EM: effector memory; N: naïve T cells; ND: not done; P: participant; TCC: T-cell clones; TCD: treated coeliac disease; UCD: untreated coeliac disease.

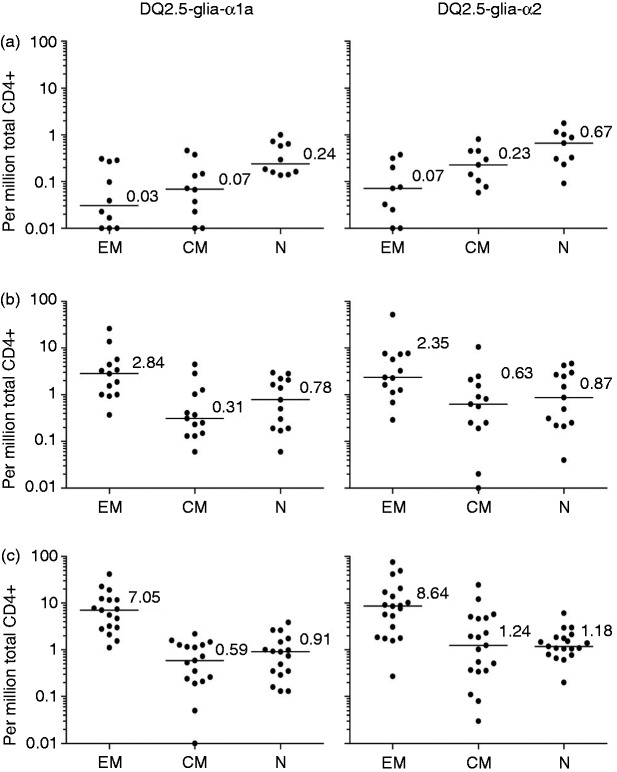

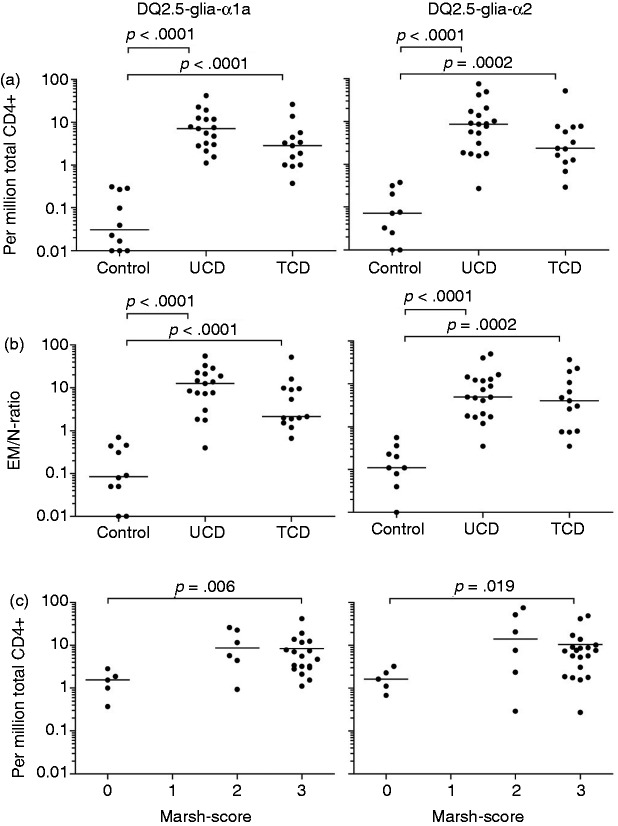

The frequency of gluten-specific T cells in peripheral blood

The frequency of CD4+ DQ2.5-glia-α1a- and the DQ2.5-glia-α2-tetramer+ cells was similar among the three participant groups for TN (respective median frequency 0.61 and 0.94 per million total CD4+ T cells) and TCM (respective median frequency 0.29 and 0.49 per million CD4+ T cells) (Figure 2). In contrast, there was a significantly higher frequency of gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ TEM in UCD, as compared to controls (p < 0.0001 for both tetramers) and in TCD compared to controls (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0002) (Table 1 and Figure 3(a)). The frequency of TEM binding either gliadin-tetramer was <0.4 per million total CD4+ T cells in control subjects. In comparison, the corresponding frequencies were ≥1 in 18 out of 19 HLA-DQ2.5+ UCD and 11 out of 13 HLA-DQ2.5+ TCD.

Figure 2.

Frequency of CD4+ gliadin-tetramer+ T cells. Number of EM, CM and N T cells binding the DQ2.5-glia-α1a-tetramer (left) and the DQ2.5-glia-α2-tetramer (right) per million total CD4+ T cells. Each participant is indicated by a closed circle. The median frequency is denoted with numbers in (a) controls, (b) TCD patients and (c) UCD patients. Frequencies below <0.01 per million are placed on the x-axis for visualization purposes.

CM: Central memory; EM: effector memory; N: naïve T cells; TCD: treated coeliac disease patients; UCD: untreated coeliac disease patients.

Figure 3.

Significantly more gliadin-tetramer+ TEM in patients compared to controls. (a) Frequency of CD4+ TEM binding the DQ2.5-glia-α1-tetramer (left) and the DQ2.5-glia-α2-tetramer (right) among controls, UCD and TCD. (b) Ratio between gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ TEM and naïve T cells (EM/N-ratio). (c) The prevalence of gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ TEM was grouped by Marsh score in those participants where duodenal biopsies were obtained. Frequencies and ratios below <0.01 per million are placed on the x-axis for visualization purposes. Each frequency and ratio is indicated by a closed circle. P values were calculated with the Mann-Whitney U test.

N: naïve T cells; TCD: treated coeliac disease patients; TEM: Effector memory T cells; UCD: untreated coeliac disease patients.

The EM/N ratio in patients and controls

In order to get a simpler and more robust parameter for the T-cell response to gluten, we divided the number of TEM by the number of TN (termed the EM/N ratio). We found this parameter more useful, as it is independent of the number of total CD4+ T cells. For both epitopes studied, we observed significant differences in the EM/N ratio between controls (all with a ratio <1, except for subject P2) and UCD (all with a ratio >1, except for subject P24), and between controls and TCD (15 out of 17, with a ratio >1 for one or both of the tetramers), as seen in Table 1 and Figure 3(b)).

Gluten-specific TEM versus duodenal changes

The histological appearance in the duodenal mucosa can be graded into normal mucosa (Marsh score 0), increased numbers of intraepithelial lymphocytes (Marsh score 1), hyperplastic lesion and crypt hyperplasia (Marsh score 2), and variable degrees of villous blunting (Marsh score 3).21,22 It is poorly understood how histological changes related to gluten ingestion develop, but gluten-specific CD4+ T cells are thought to play a crucial role.9,10,12 We looked at whether the observed variations in the frequency of gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ TEM in peripheral blood correlated with the Marsh score of CD patients at the time of blood analysis (Figure 3(c)). We found a significantly higher frequency of DQ2.5-glia-α1a and DQ2.5-glia-α2 -specific CD4+ TEM in participants with a Marsh score 3, compared to those with a Marsh score 0. Very few of our CD patients had Marsh score 2 and the frequency of gliadin-tetramer+ cells among these was variable.

Gut homing of gluten-specific TEM

A few CD patients had either frequencies of gliadin-tetramer+ TEM or an EM/N ratio similar to controls. To test whether patients and controls could be further distinguished, we analyzed CD4+ gliadin-tetramer positive versus negative cells in four TCD and four controls, for the gut-homing marker integrin-β7 in the population of cells obtained after tetramer bead enrichment (Figure 4(a) and Figure 4(b)). In TCD, significantly more gliadin-tetramer+ TEM (80–95%), compared to gliadin-tetramer- cells, expressed integrin-β7. In contrast, integrin-β7 expression did not exceed background in the gliadin-tetramer+ TEM of controls.

Integrin-β7 forms gut-homing dimers with α4- or αΕ-subunits; and a skin-homing dimer with the α1 chain. Peripheral blood from one TCD was stained for the CLA. None of the gliadin-tetramer+ TEM in this TCD expressed the skin-homing marker (Figure 4(c)), indicating that the observed integrin-β7 expression is associated with gut-homing rather than skin-homing.

Discussion

We here demonstrate that gluten-reactive T cells in peripheral blood can be characterized and enumerated directly ex vivo in TCD, UCD and controls without oral gluten challenge. Gut-homing gliadin-tetramer+ CD4+ TEM were significantly more frequent in CD patients than controls. These cells likely reflect an antigen-driven, CD-associated T-cell response, and there is a potential for using this parameter for the diagnostic work-up of CD.

All UCD and TCD had either a ratio of TEM/TN cells >1 or a frequency of TEM specific for one or both of the epitopes DQ2.5-glia-α1a or DQ2.5-glia-α2 > 1 per million total CD4+ T cells. The only exception was TCD P50 (EM/N ratio 0.3). Still, the gliadin-tetramer+ TEM of this treated patient expressed integrin-β7 significantly above background and thus, is distinguishable from the tetramer+ TEM of controls. In comparison, all controls (except P2) had both the EM/N ratio <0.8 and the frequency of gliadin-tetramer+ TEM < 0.4 per million total CD4+ T cells. We strongly suspect that the anonymous donor P2 had undiagnosed CD. The combination of integrin-β7+ TEM percentage with the EM/N ratio seemed to give a good discrimination of patients versus controls. This notion must be corroborated in future studies.

GFD will often normalize diagnosis-dependent parameters like histology and disease-specific antibodies in CD patients.23 Still, proliferating intraepithelial lymphocytes,24 duodenal TG2-specific antibody-secreting cells25 and duodenal gluten-specific T cells can be detected in TCD.9 These data indicate a persistent immune response to gluten in many TCD. Our finding supports this notion, as gliadin-tetramer+ EM cells were detected in the blood of all included TCD, despite normal mucosa and negative antibody titers in many of them. The persistent T-cell response to gluten in TCD may be explained by long-lived memory T cells,26 local IL-15 production27 or sporadic exposure to small amounts of gluten antigen. Importantly, we are able to detect a persistent T-cell response in blood that can prove to be very helpful in diagnosing patients that are already on a GFD, without previously confirmed CD diagnosis.

Notably, we found a statistically significant difference in TEM numbers between CD patients with Marsh score 0 and 3, despite the small group sizes and the issue of CD lesion patchiness.28 Although gluten-specific T cells may not be directly responsible for the remodeling of the intestinal mucosa, they can drive inflammation through pro-inflammatory mediators that activate intraepithelial cytotoxic T lymphocytes.29 As gliadin-tetramer+ TEM cells in the blood of CD patients show high expression of gut-homing markers and use T-cell receptors typical of CD lesion-derived T cells,30 they likely have intestinal origin and reflect the disease-driving gluten-reactive T-cell response in the lamina propria. Whether the latter is the case could be further tested in studies where the T-cell receptor sequences of intestinal and peripheral blood gliadin-tetramer+ cells are compared.

The rate of the proliferative response to peptide stimulation seemed to be phenotype-dependent. In general, the fraction of TCC proliferating after peptide stimulation was lower among TEM from controls, TN from CD patients and TCM overall. Notably, we were not able to confirm gluten reactivity of the few gliadin-tetramer+ memory cells of our controls, except for two TCM clones. One might speculate that tetramer+ TEM from controls represent gluten-specific regulatory T cells or some other T-cell phenotypes that do not necessarily respond to antigen stimulation with proliferation. Overall, poor yield of specific tetramer-sorted blood cells could possibly be explained by tetramer-induced cell apoptosis31 and by a certain degree of background staining.32 Nevertheless, we believe that this protocol can be used in further studies on gluten-reactive T cells of CD patients and controls, give important insights into CD pathogenesis and accommodate a search for disease-specific T-cell receptors.33

CD patients can present with histological changes in the small intestine, but negative serology,6 and vice versa.7 This has led to an ongoing debate on the diagnostic criteria for CD.7,34 A large number of individuals are also on a GFD without any confirmed CD diagnosis35 reducing the sensitivity of currently available diagnostic tools substantially.

We report a significant difference in the number of gluten tetramer+ TEM in UCD and TCD, and in the gut-homing of these cells in CD patients compared to controls without performing a gluten challenge. Flow cytometry is already routinely used in clinical work-up. The current protocol allows analysis with 50 mL of blood; and this volume may be further reduced, if gluten epitopes are combined. Tetramerized HLA-DQ8- and HLA-DQ2.2-restricted gluten epitopes should also be tested with the current approach, to include also these minor groups of CD patients. Moreover, HLA tetramer production may be optimized in an industrial setting, with production costs similar to other diagnostic assays. Thus, we will argue that this minimally invasive, ex-vivo method may find use in clinical practice, particularly in patients with vague diagnostic conditions, or in cases where a gastroduodenoscopy is inappropriate or undesirable, as well as in undiagnosed individuals adhering to a GFD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all the subjects whom donated biological material to this study, Marie K Johannesen and Louise F Risnes for technical assistance, Bjørg Simonsen for tetramer production and Yan Zhang for assisting with cell sorting.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway and the Health Authority of South-Eastern Norway. Asbjørn Christophersen was supported by the University of Oslo (PhD fellowship). No funding source had any role in the design, conduct or reporting of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 2012; 62: 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wieser H. Chemistry of gluten proteins. Food Microbiol 2007; 24: 115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 1731–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabo IR, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 54: 136–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). Institute medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2006; 131: 1977–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickey W, Hughes DF, McMillan SA. Reliance on serum endomysial antibody testing underestimates the true prevalence of coeliac disease by one fifth. Scand J Gastroenterol 2000; 35: 181–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurppa K, Collin P, Viljamaa M, et al. Diagnosing mild enteropathy celiac disease: A randomized, controlled clinical study. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 816–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sollid LM. Coeliac disease: Dissecting a complex inflammatory disorder. Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2: 647–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundin KE, Scott H, Hansen T, et al. Gliadin-specific, HLA-DQ (alpha 1*0501,beta 1*0201) restricted T cells isolated from the small intestinal mucosa of celiac disease patients. J Exp Med 1993; 178: 187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molberg Ø, Kett K, Scott H, et al. Gliadin specific, HLA DQ2-restricted T cells are commonly found in small intestinal biopsies from coeliac disease patients, but not from controls. Scand J Immunol 1997; 46: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shan L, Molberg O, Parrot I, et al. Structural basis for gluten intolerance in celiac sprue. Science 2002; 297: 2275–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundin KE, Scott H, Fausa O, et al. T cells from the small intestinal mucosa of a DR4, DQ7/DR4, DQ8 celiac disease patient preferentially recognize gliadin, when presented by DQ8. Hum Immunol 1994; 41: 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson RP, Degano P, Godkin AJ, et al. In vivo antigen challenge in celiac disease identifies a single transglutaminase-modified peptide as the dominant A-gliadin T-cell epitope. Nat Med 2000; 6: 337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raki M, Fallang LE, Brottveit M, et al. Tetramer visualization of gut-homing gluten-specific T cells in the peripheral blood of celiac disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 2831–2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pepper M, Jenkins MK. Origins of CD4(+) effector and central memory T cells. Nat Immunol 2011; 12: 467–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quarsten H, McAdam SN, Jensen T, et al. Staining of celiac disease-relevant T cells by peptide-DQ2 multimers. J Immunol 2001; 167: 4861–4868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moon JJ, Chu HH, Pepper M, et al. Naive CD4(+) T-cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity 2007; 27: 203–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, et al. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature 1999; 401: 708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molberg Ø, McAdam SN, Lundin KE, et al. Studies of gliadin-specific T cells in celiac disease. Methods Mol Med 2000; 41: 105–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwok WW, Tan V, Gillette L, et al. Frequency of epitope-specific naive CD4+ T cells correlates with immunodominance in the human memory repertoire. J Immunol 2012; 188: 2537–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marsh MN, Crowe PT. Morphology of the mucosal lesion in gluten sensitivity. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol 1995; 9: 273–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: Time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999; 11: 1185–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sulkanen S, Halttunen T, Laurila K, et al. Tissue transglutaminase autoantibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in detecting celiac disease. Gastroenterology 1998; 115: 1322–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olaussen RW, Karlsson MR, Lundin KE, et al. Reduced chemokine receptor 9 on intraepithelial lymphocytes in celiac disease suggests persistent epithelial activation. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 2371–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Niro R, Mesin L, Zheng NY, et al. High abundance of plasma cells secreting transglutaminase 2-specific IgA autoantibodies with limited somatic hypermutation in celiac disease intestinal lesions. Nat Med 2012; 18: 441–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pepper M, Linehan JL, Pagan AJ, et al. Different routes of bacterial infection induce long-lived TH1 memory cells and short-lived TH17 cells. Nat Immunol 2010; 11: 83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meresse B, Chen Z, Ciszewski C, et al. Coordinated induction by IL15 of a TCR-independent NKG2D signaling pathway converts CTL into lymphokine-activated killer cells in celiac disease. Immunity 2004; 21: 357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pais WP, Duerksen DR, Pettigrew NM, et al. How many duodenal biopsy specimens are required to make a diagnosis of celiac disease? Gastrointest Endosc 2008; 67: 1082–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jabri B, Sollid LM. Tissue-mediated control of immunopathology in coeliac disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9: 858–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiao SW, Christophersen A, Lundin KE, et al. Biased usage and preferred pairing of alpha- and beta-chains of TCRs specific for an immunodominant gluten epitope in coeliac disease. Int Immunol 2014; 26: 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knabel M, Franz TJ, Schiemann M, et al. Reversible MHC multimer staining for functional isolation of T-cell populations and effective adoptive transfer. Nat Med 2002; 8: 631–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geiger R, Duhen T, Lanzavecchia A, et al. Human naive and memory CD4+ T-cell repertoires specific for naturally processed antigens analyzed using libraries of amplified T cells. J Exp Med 2009; 206: 1525–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiao SW, Raki M, Gunnarsen KS, et al. Post-translational modification of gluten shapes TCR usage in celiac disease. J Immunol 2011; 187: 3064–3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaukinen K, Maki M, Partanen J, et al. Celiac disease without villous atrophy: Revision of criteria called for. Dig Dis Sci 2001; 46: 879–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubio-Tapia A, Ludvigsson JF, Brantner TL, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 1538–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials