Abstract

The Translationally Controlled Tumor Protein (TCTP) is a highly conserved protein at the level of sequence, considered to play an essential role in the regulation of growth and development in eukaryotes. However, this function has been inferred from studies in a few model systems, such as mice and mammalian cell lines, Drosophila and Arabidopsis. Thus, the knowledge regarding this protein is far from complete. In the present study bioinformatic analysis showed the presence of one or more TCTP genes per genome in plants with highly conserved signatures and subtle variations at the level of primary structure but with more noticeable differences at the level of predicted three-dimensional structures. These structures show differences in the “pocket” region close to the center of the protein and in its flexible loop domain. In fact, all predictive TCTP structures can be divided into two groups: (1) AtTCTP1-like and (2) CmTCTP-like, based on the predicted structures of an Arabidopsis TCTP and a Cucurbita maxima TCTP; according to this classification we propose that their probable function in plants may be inferred in principle. Thus, different TCTP genes in a single organism may have different functions; additionally, in those species harboring a single TCTP gene this could carry multiple functions. On the other hand, in silico analysis of AtTCTP1-like and CmTCTP-like promoters suggest that these share common motifs but with different abundance, which may underscore differences in their gene expression patterns. Finally, the absence of TCTP genes in most chlorophytes with the exception of Coccomyxa subellipsoidea, indicates that other proteins perform the roles played by TCTP or the pathways regulated by TCTP occur through alternative routes. These findings provide insight into the evolution of this gene family in plants.

Keywords: Translationally Controlled Tumor Protein, Arabidopsis thaliana, evolution, phylogeny, GTP-binding pocket

Introduction

The Translationally Controlled Tumor Proteins, or TCTP, constitute a protein family found exclusively in eukaryotes, which are central for growth regulation (Bommer et al., 2002). Sequence comparison of TCTP sequences reveals a high degree of conservation among all eukaryotic phyla (Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2008). Such conservation, as well as its nearly ubiquitous expression underscores its essential role in the regulation of growth and development of different organisms (Thaw et al., 2001; Bommer and Thiele, 2004; Amson et al., 2013).

Currently, work on TCTP has focused mostly on animals, particularly models like human, mice and Drosophila, which has shown it to be involved in several biological processes such as cell growth, cell cycle progression, differentiation, malignant transformation, protection against various stress conditions and apoptosis (Amson et al., 2013). Studies on TCTP function in plants have been conducted with few experimental systems, mostly Arabidopsis. Although the molecular function of TCTP in plants has not been completely established yet, it is likely that in broad terms its function is similar, e.g., growth and developmental regulation since such function appears to be conserved across kingdoms; indeed a Drosophila TCTP mutant can be rescued with the corresponding Arabidopsis TCTP gene, and vice versa (Brioudes et al., 2010). Extant data suggest that TCTP is constitutively expressed at high levels in most tissues in different plants species; there is also evidence that TCTP expression is affected by a variety of conditions (Bommer and Thiele, 2004; Nagano-Ito and Ichikawa, 2012; Amson et al., 2013). Indeed, TCTP mRNA levels vary considerably in response to a wide range of extracellular stimuli and in multiple seemingly unrelated cellular processes (Bommer and Thiele, 2004).

The first plant TCTP mRNA sequence was obtained in Medicago sativa (Pay et al., 1992). The notion that its expression in plants correlates positively with growth was supported by the fact that TCTP mRNA accumulated in the root cap of Pisum sativum, a region undergoing continuous cell division (Woo and Hawes, 1997). Furthermore, possible functions related to photoperiodism and flowering in Pharbitis nil have been suggested (Sage-Ono et al., 1998). TCTP is regulated in response to a wide range of stimuli, such as aluminum (Ermolayev et al., 2003), damage caused by Hg2+ (Wang et al., 2012) and NaCl (Vincent et al., 2007; Cao et al., 2010), heat, cold, and drought (Kim et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013), as well as growth regulators such as auxins, ABA (Berkowitz et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2012), and methyl jasmonate (Li et al., 2013). TCTP also seems to be involved in response to pathogens such as Pseudomonas syringae (Jones et al., 2006) and Erysiphe grαminis, the causal agent of powdery mildew in wheat (Li et al., 2010).

On the other hand, TCTP has been detected in the phloem sap of Ricinus communis and Cucurbita maxima, suggesting its phloem long-distance movement. This in turn suggests that these proteins, at least in some species, act in a non-cell-autonomous manner (Barnes et al., 2004; Aoki et al., 2005; Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2006). It is worth mentioning that lupin TCTP mRNA is present in the phloem sap transcriptome, and the pumpkin TCTP mRNA has been found in phloem sap exudates (Rodriguez-Medina et al., 2011; Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2013).

High expression levels of this gene have also been detected in embryo and endosperm during embryo development in Jatropha curcas and Ricinus communis, indicating that TCTP participates in this process (Lu et al., 2007; Qin et al., 2011). Indeed, loss of function of Arabidopsis AtTCTP1 leads to delayed embryo development (Brioudes et al., 2010). AtTCTP1 is expressed throughout plant tissues and developmental stages, particularly in meristematic and expanding cells; moreover, and by analogy to Drosophila TCTP, it might act as a mediator of TOR activity via interaction with Rho GTPases in a similar manner to non-plant systems (Berkowitz et al., 2008), although the involvement of TCTP in the TOR pathway is still debated (Wang et al., 2008). Other results suggest that AtTCTP1 controls mitotic growth and cell division but not cell expansion in plants (Brioudes et al., 2010) and cell cycle progression (Nakkaew et al., 2010).

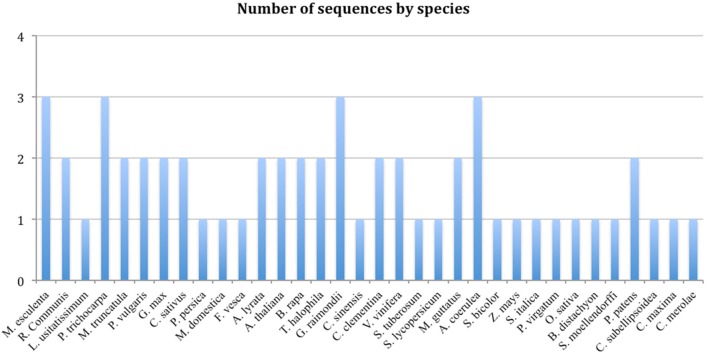

There are variable numbers of TCTP genes in different organisms, while mammals harbor the highest number of TCTP-like sequence per genome (for example, human, mouse and rat each harbor 3 TCTP genes and a larger number of pseudogenes), plants and fungi in general contain one or two TCTP genes (Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2008; Figure 1). It is possible that in organisms with multiple TCTP genes these are redundant; however, in some cases it is also possible that each performs non-overlapping or partially overlapping functions.

Figure 1.

Number of TCTP sequences by plant species (Source: Phytozome).

Currently, several TCTP genes have been isolated and cloned from different plants species. However, there are few studies regarding their functional characterization. The following table presents information about TCTP in different plant species and its identified function (Table 1). These published data suggest that TCTP not only regulates general growth but also carries out functions that are specific for plants, such as auxin homeostasis, regulation of stomatal closure, defense response to bacteria, positive regulation of microtubule depolymerization, drought recovery, pollen tube growth, among others. Based on this wide range of functions and the different TCTP versions present in plants, we suggest a specialization of functions (or division of labor) of this multifunctional protein. In the present work we propose that, based on an Arabidopsis (AtTCTP1) and a Cucurbita maxima (pumpkin) TCTP (CmTCTP) genes, their probable functions and predicted three-dimensional structures, there are two groups of TCTP genes, an AtTCTP1-like clade and a CmTCTP-like clade, and their respective functions may be inferred from such grouping. We also found that only one chlorophyte, among those whose genomes have been sequenced, harboring a TCTP gene, with possible implications on land plant evolution.

Table 1.

List of TCTP genes present in different plant species and their functions.

| Species | Gene | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Bank accession number | ||

| Jatropha curcas (Physic Nut) | JcTCTP EF091818 | Regulation of the endosperm development (Qin et al., 2011) |

| Cucurbita maxima (Pumpkin) | CmTCTP DQ304537 | Non-cell-autonomous function and long-distance movement of phloem proteins (Aoki et al., 2005; Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2006). |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Thale cress) | AtTCTP NM112537 | Regulator of mitotic growth and cell cycle duration (Brioudes et al., 2010) Growth regulator, auxin homeostasis, root hair development and lateral root formation (Berkowitz et al., 2008) Drought tolerance, ABA-mediated stomatal closure, tubulin-, and calcium-binding properties (Kim et al., 2012) |

| Fragaria ananassa (Strawberry) | FaTCTP Z86091 | Fruit ripening? (Lopez and Franco, 2006) |

| Elaeis guineensis (Oil palm) | EgTCTP AAQ87663.1 | Cell growth and cell cycle progression (Nakkaew et al., 2010) |

| Brassica oleracea (Cabbage) | BoTCTP AF418663 | Growth regulation and defense response to cold, high temperature, and salinity stresses (Cao et al., 2010). |

| Pharbitis nil (Morning glory) | PnTCTP AB007759 | Photoperiodism, flowering? (Sage-Ono et al., 1998) |

| Oriza sativa (Rice) | OsTCTP BAA02151 | Response to Hg2+ stress (Wang et al., 2012) |

| Nicotiana tabacum (Tobacco) | NtTCTP AF107842 | Cell cycle progression (Brioudes et al., 2010) |

| Triticum aestivum (Wheat) | TaTCTP AF508970 | Powdery mildew resistance? (Li et al., 2010) |

| Ricinus communis (Castor bean) | RcTCTP RCOM_1433410 | Endosperm formation? (Lu et al., 2007) |

| Vitis vinifera (Grape Vine) | VvTCTP NC_012020 | Response to water deficit and salinity (Vincent et al., 2007) |

| Manihot sculenta (Cassava) | MsTCTP AAM55492 | Storage root formation (de Souza et al., 2004) |

| Hevea brasiliensis (Rubber tree) | HbTCTP JN200814 | Response to ethrel, wounding, methyl jasmonate, low temperature, high salt, H2O2, and drought (Li et al., 2013) |

| Pisum sativum (Common pea) | PsTCTP AAB19090 | Cell division (Woo and Hawes, 1997) |

Materials and methods

TCTP sequences

Protein sequences used in this analysis were retrieved from Phytozome database (http://www.phytozome.net/). As a starting point, the virtual translation derived from the nucleotide sequence of Cucurbita maxima TCTP (CmTCTP; Genbank accession number DQ304537) was obtained from the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/). Afterwards, a BLAST search was carried out using the corresponding CmTCTP protein sequence as query into the proteome Phytozome database. Based on this search, sequences representative of different plant species were selected for further study. Sequences that diverged from the consensus and were thus probably sequencing artifacts were not used for further analysis.

Identity and similarity of TCTP protein sequences

The selected protein sequences of TCTP from different organisms were entered into MatGAT software version 2.01 (Matrix Global Alignment Tool) to calculate sequence similarity and identity (http://bitincka.com/ledion/matgat/). The series of pairwise alignments (shown as distance matrix) were inferred using the BLOSUM62 scoring matrix and the following parameters: number of first gap 10, gap extension 2. The analysis involved 59 amino acid sequences. Values were expressed as percent of similarity and identity between the TCTP protein sequences from different plant species compared with AtTCTP1 (At3g16640) from A. thaliana and CmTCTP from C. maxima.

Phylogenetic analysis

The amino acid sequences chosen previously were aligned with the MUSCLE program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/muscle) using the profile method (Edgar, 2004). ProtTest program version 2.4 (Abascal et al., 2005) was used for the selection of the model of protein evolution that best fitted the set of sequences. Evolutionary analysis was conducted in PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al., 2010) and the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Program (MEGA) version 5 (Tamura et al., 2014). The evolutionary phylogenetic reconstruction (shown as dendrogram) was inferred using the LG+G evolution method and the following parameters: number of substitution rate categories 4, gamma shape parameter 0.642, and 1000 replicate bootstrap search with heuristic search options. Branches with <60% bootstrap support were collapsed. The tree was rooted with the Cyanidioschyzon merolae TCTP sequence, which belongs to the red algae group. The analysis involved 59 amino acid sequences.

Predicted tertiary structure of TCTP

Full-length protein sequences were selected from the Phytozome database (http://phytozome.net) and refined through a comparison with the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Amino acid sequences were submitted to the automated protein structure homology-modeling program server SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/), this server builds a model for each protein target using as templates, homologous protein structures which have been experimentally determined (Arnold et al., 2006; Kiefer et al., 2009). Swiss PDB Viewer application (http://www.expasy.org/spdbv/) was used for visualizing predictive 3D structures (Guex and Peitsch, 1997).

Promoter analysis

Upstream sequences (1.0 kbp) from TCTP genes were retrieved from the Phytozome database (http://www.phytozome.net/). The list of genes and the species from which these upstream regions were obtained is listed in Table S1. These were classified according to their structural similarity to either AtTCTP1 or CmTCTP proteins from Arabidopsis and pumpkin, respectively. Also, since several of these genes have not been characterized, their 5′UTRs have not been defined; in these cases, 1 kb sequences upstream of the start codon were analyzed.

Promoter analysis was performed using the MEME software (http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/meme.html, Bailey et al., 2006) with the following settings: one or more occurrence, per sequence, and a 10 base motif length. Based on sequence analysis, using ALIGNACE, as well as visual inspection of the promoter sets, it was determined that CT/GA repeats were present more than once in the analyzed upstream sequences and, thus, the ZOOPS and OOPS models were not employed. As background model the shuffled sequences were used and also analyzed with MEME (http://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/about.html). Motifs were graphically represented with the WEBLOGO program (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi). As background models, the shuffled sequences were likewise analyzed using the MEME algorithm.

Results

Plants harbor variable numbers of TCTP sequences

A BLASTP search was carried out for each of the plant species for which its genome has been sequenced using the CmTCTP protein sequence as query, after which the corresponding TCTP sequences were retrieved. The list of 59 TCTP sequences from different plant species used in this study is shown (Table S1). Based on the TCTP amino acid sequences retrieved from Phytozome database, the species that have only a single TCTP gene are: Linum usitatissimum, Cucurbita maxima, Prunus persica, Malus domestica, Fragaria vesca, Citrus sinensis, Solanum tuberosum, Solanum lycopersicum, Sorghum bicolor, Zea mays, Setaria italica, Panicum virgatum, Oryza sativa, Brachypodium distachyon, Selaginella moellendorffi, Coccomyxa subellipsoidea and Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Species that harbor 2 TCTP gene copies are: Ricinus communis, Medicago truncatula, Phaseolus vulgaris, Glycine max, Cucumis sativus, Cucumis melo, Arabidopsis thaliana, Arabidopsis lyrata, Brassica rapa, Thellungiella halophila, Citrus clementina, Citrullus lanatus, Vitis vinífera, Mimulus guttatus and Physcomitrella patens. Finally, the species that harbors 3 TCTP genes are: Manihot esculenta, Populus trichocarpa, Gossypium raimondii and Aquilegia coerulea (Table 2).

Table 2.

Structural classification of TCTP from plants.

| Organism | AtTCTP1-like | CmTCTP-like |

|---|---|---|

| C. subellipsoidea | C-169_65285 | |

| C. meroleae | CMQ113C | |

| P. patens | XP_001757363; XP_001758666 | |

| S. moellendorffi | 179722 | |

| O. sativa | Os11g43900 | |

| B. distachyon | Bradi4g10920 | |

| S. bicolor | XP_002453140 | |

| Z. mays | GRMZM2G108474_T01 | |

| S. italica | Si026772m | |

| A. coerulea | Aquca_003_00740 | Aquca_017_00176; Aquca_035_00202 |

| P. virgatum | Pavirv00039226m | |

| S. tuberosum | PGSC0003DMT400063579 | |

| S. lycopersicum | Solyc01g099780.2 | |

| M. guttatus | Migut.G00151; Migut.N02086 | |

| V. vinífera | GSVIVT01017723001; GSVIVT01031135001 | |

| C. sinensis | 1.1g030941m | |

| C. clementina | Ciclev10006071m | Ciclev10002699m |

| G. raimondii | Gorai.005G060700 | Gorai.007G300300; Gorai.013G126000 |

| T. halophila | BAJ33998 | 10022380m |

| B. rapa | Bra022172 | Bra001637; Bra021187 |

| A. lyrata | XP_002885160 | XP_002884515 |

| G. max | Glyma10g29240; Glyma09g04950 | |

| P. vulgaris | Phvul.007G197200; Phvul.009G248700 | |

| M. truncatula | Medtr1g083350; Medtr6g071090 | |

| F. vesca | mRNA06814.1-v1.0-hybrid | |

| M. domestica | MDP0000164046 | |

| P. persica | ppa009639m | |

| C. sativus | Cucsa.253020 | Cucsa.181820 |

| C. melo | Melo3c006670p1 | Melo3C015297P1 |

| C. lanatus | Cla021747 | Cla005200 |

| C. maxima | N.D. | ABC02401 |

| P. trichocarpa | Potri.005G024800; Potri.008G226500 | Potri.010G013400 |

| L. usitatissimum | Lus10033959 | |

| R. communis | 29726.m004052; 30128.m008835 | |

| M. esculenta | cassava4.1_025245m | cassava4.1_017738m; cassava4.1_017756m |

| C. rubella | EOA33129.1 | EOA31592.1 |

| C. papaya | evm.model.supercontig_1597.1; evm.model.supercontig_327.3 |

Modeling of predictive 3D protein structure for each plant TCTP was carried out (Figure S4) and structure comparison was assessed to classify each plant TCTP based on their predictive structural relationship to either Arabidopsis thaliana AtTCTP1 or the Cucurbita maxima CmTCTP.

Pairwise BLAST is used to calculate similarity, but its limitations are that only two sequences may be analyzed at one time and percent of similarity/identity is based on local alignment instead of a global alignment. Matrix Global Alignment Tool (MatGAT) is a simple, easy to use similarity/identity matrix generator that calculates the similarity and identity between every pair of sequences in a given data set without requiring pre-alignment of the data. The program performs a series of pairwise alignments using the Myers and Miller global alignment algorithm, calculates similarity and identity, and then places the results in a distance matrix (Campanella et al., 2003). Sequences were aligned with Arabidopsis AtTCTP1 and CmTCTP as type sequences, because biological function of the first one is better known, while the latter, albeit less well studied, appears to have a different function according to results in our group (see below; Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2013; Toscano-Morales et al., submitted).

Sequence comparison at the amino acid level of TCTPs from different species showed a similarity in the range of 80.4–98.2 and 82.1–94% compared with At3g16640 (AtTCTP1) and CmTCTP, respectively (Table S2). On the other hand, the percent of identities ranged from 70.2–95.2 to 71.2–88.1 with the reference AtTCTP1 and CmTCTP sequences respectively. These ranges did not include the percent of similarities/identities with the microalgae C. subellipsoidea and the red algae C. merolae.

Phylogeny of plant TCTP protein sequences cannot be resolved satisfactorily

Protein sequences used in this analysis were retrieved from the Phytozome database. The amino acid sequences chosen were aligned with the MUSCLE program (Figure S1). A phylogeny of the aforementioned sequences was generated by MEGA 5.0 software by using the LG+G method with 1000 bootstrap replications. Phylogenetic analysis based on the TCTP protein sequence from different organisms groups may be informative with respect to the evolution of TCTP per se. But this also depends on which outgroup was used to root the tree. If this consists of a protein with a similar function, the tree may reflect the functional similarities between these proteins. On the other hand, an outgroup consisting of a sequence derived from an early branching event may yield more information on the phylogenetic relationship between the taxa harboring this protein (Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2008). For this analysis, TCTP sequence from the red algae C. merolae was used as outgroup. However, the resulting tree could not be resolved satisfactorily (Figure S2).

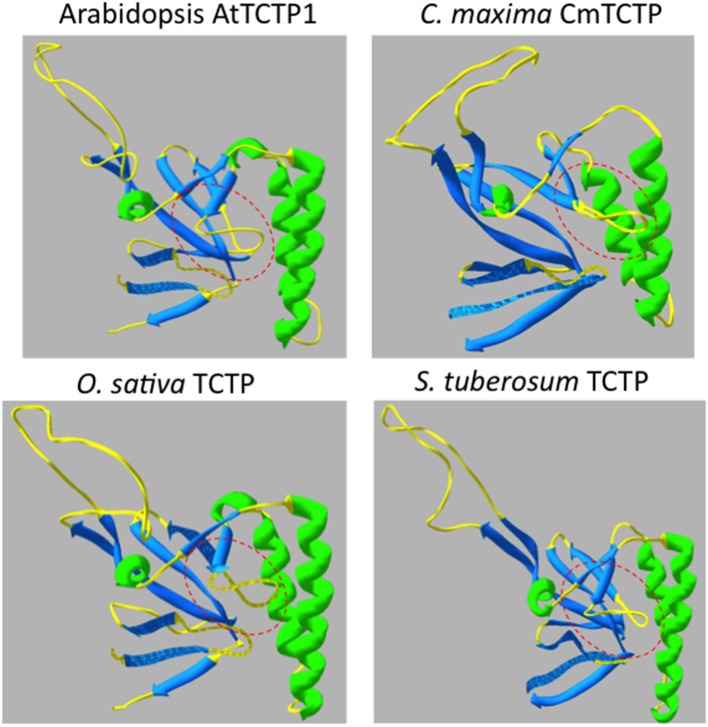

Predictive protein structure of plant TCTPs as a parameter to establish potential functional differences

Since phylogenetic analysis did not provide sufficient information to suggest functional differences between plant TCTP sequences could be inferred; thus, other criteria were used to help establish such differences, if any. We had previously reported that while TCTP structures are highly conserved, there are subtle differences among some members of this family. Indeed, TCTP from Plasmodium falciparum and P. knowlesi harbor an extra α-helix close to the N terminus, not found in other TCTPs (Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2008); this causes a structural distortion in the pocket region that may be involved in the interaction with GTPases. We have recently found that such structural differences are reflected in the capacity of human and P. falciparum TCTP to induce B cell proliferation, as well as its incorporation into these cells (Calderón-Pérez et al., 2014). Thus, we assumed that plant TCTPs could also show structural differences from which functional specialization could be deduced. Therefore, TCTP amino acid sequences from each plant species whose genome has been sequenced were obtained from the Phytozome database, followed by direct comparison to sequences from other databases in order to avoid ESTs or repeated sequences. A total of 59 amino acid sequences were submitted to the automated protein structure homology-modeling server SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/) that generated a homology model for each sequence. The respective model was visualized and modified to generate the 3D-models using the Swiss-Pdviewer 4.10 application.

The Arabidopsis genome harbors two TCTP genes, AtTCTP1 and AtTCTP2 (At3g16640 and At3g05540, respectively). The important role of the former in general growth and development has been described before. We have reported that the pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima) TCTP (CmTCTP) induces cell proliferation and regeneration, in conjunction with A. rhizogenes rol genes, and is phloem-mobile; thus, it can be considered that it is not a functional homolog of AtTCTP1 (Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2013). These results suggest that all TCTPs fall within these two broad groups, one of them related to AtTCTP1, while the other one more related to CmTCTP.

AtTCTP1 and CmTCTP were used as reference structures to determine whether this “division of labor” can be extrapolated to other plant species. It may be assumed that such functional specialization occurs in plants harboring more than one TCTP gene, while in those harboring a single TCTP gene this would perform the combined functions of AtTCTP1 and CmTCTP. Finally this specialization would be expected only in land plants, and especially in vascular plants.

The 3D-predictive structures of all TCTPs were generated using Swiss Model; the templates used to obtain such structures are listed in Table S3. These structures presented a quite similar conformation. However, we found the “pocket” region near the center of the protein (and which may be the GTPase-binding domain, at least in fungi and animals) and its flexible loop as the most divergent regions among plant TCTPs. Interestingly, AtTCTP1 and CmTCTP meet this criterion of divergence. Indeed, the latter is predicted to be structurally similar to a group of TCTPs including StTCTP and FvTCTP, while AtTCTP1 is more related to other TCTP versions such as Oryza sativa TCTP (OsTCTP) (Figure 2). The predictive structures of diverse TCTPs support the notion that these proteins fall into two groups, AtTCTP1-like and CmTCTP-like (Table 2; Figures S3, S4), and based on these their possible functions can be inferred.

Figure 2.

Structural comparison of Arabidopsis TCTPs. The “pocket” structure (highlighted in dashed red lines) and the flexible loop orientation indicate probable structural differences between these two TCTPs. In the bottom there are two examples of the structural classification made for all Plant TCTPs, retrieved from Phytozome database (http://phytozome.net). O. sativa TCTP (OsTCTP) is structurally related to AtTCTP1 while S. tuberosum (StTCTP) is predicted to be structurally similar to CmTCTP.

Intriguingly, we found no TCTP genes in several chlorophytes, e.g., Ostreococcus lucimarinus, Micromonas pusilla, Volvox carteri, and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, with the exception of Coccomyxa subellipsoidea, which harbors one TCTP gene. This suggests that other proteins perform the roles played by TCTP in most plants are regulated through alternative routes. In contrast, the red algae Cyanidioschyzon meroleae harbors one TCTP gene.

The moss Physcomitrella patens harbors two TCTP genes, which encode a protein structurally similar to AtTCTP1 and the other resembling CmTCTP. In contrast, the tracheophyte Selaginella moellendorffi and several monocots (such as Brachypodium dystachion, Oryza sativa, Sorghum bicolor, Zea mays, Setaria italic, and Panicum virgatum) have only one gene coding for TCTP (all similar to AtTCTP1). Several eudicots harbor only one gene, but others contain two or more TCTP genes (Table 2). In the cases in which species have only one TCTP gene, this is usually AtTCTP1-like, as mentioned previously; but in some cases it resembles more CmTCTP (as in G. max, P. vulgaris, and M. domestica). Since the complete genome of pumpkin is not yet available, it is possible that it harbors an additional TCTP gene, which on a speculative note would be AtTCTP1-like protein. Indeed, considering that C. melo and C. sativus also harbor two copies of a TCTP gene, an AtTCTP1-like and a CmTCTP-like gene in each case, this is likely.

AtTCTP1-like and CmTCTP-like upstream regions show different motif frequencies

Bioinformatic analyses of the upstream sequences from TCTP genes in plants identified common motifs in their sequences. Both sets of genes display overrepresented CT/GA motifs (motif 1) with an extremely low E value, indicating that these sets are expressed in vascular and/or rapidly growing tissues (Ruiz-Medrano et al., 2011; Figure 3). However, since the E value for the CmTCTP-like gene promoters is 12 orders of magnitude lower than for the corresponding AtTCTP1-like gene promoters, it is possible that there are differences in the expression levels or in their tissue-specific expression. On the other hand, the AtTCTP1-like promoters motif 2 is quite different from the corresponding motif 2 from the CmTCTP-like promoters, the former being an AC-rich element with a lower E value. Both gene promoters motif 3 sets is an A-rich element, quite common in upstream regulatory sequences. The shuffled sequences showed overrepresented motifs with very high (i.e., non-significant) E-values (101–106). These results suggest that the expression profiles of AtTCTP1-like and CmTCTP-like gene promoters may not overlap completely.

Figure 3.

MEME analyses of the TCTP promoters. Consensus sequences identified in the promoters regions for both AtTCTP1-like and CmTCTP-like. Only the three motifs having the lowest E-values are shown.

Discussion

The known TCTP interactome indicates a wide variety of activities such as microtubule organization, inhibition of cell death, translation and ribosome function, DNA processing and repair, and modulation of the immune response, among several others (Nagano-Ito and Ichikawa, 2012; Amson et al., 2013). This translates to roles in general growth and developmental regulation, which in plants are less well known. Plant TCTPs show identities at the amino acid in the range of 70.2–95.2% and similarities of 80.4–98.2%, which support the notion of highly conserved functions for these proteins (See Table S2).

However, because of all these activities it is not clear whether TCTP is a multifunctional protein or if several closely related sequences have subtly different biochemical properties; this is especially relevant in cases where there is more than one gene per genome. For example, in humans, there are four TCTP genes, one of them corresponding to the histamine release factor (HRF), which is secreted. It is not known if this is the only TCTP that is secreted. Similarly, it is not clear if these genes display a common expression pattern. It is reasonable to assume that there is functional specialization among them. Another general assumption is that these proteins are structurally similar; however, our group has found that in some particular cases subtle structural differences underlie functional variations in TCTP. Indeed, the P. falciparum and P. knowlesi TCTP harbor an additional α-helix in the N-terminal domain (amino acids 22–30), which introduces an overall distortion in its structure, particularly in the central pocket region which may be involved in the recognition and binding of GTPases such as guanine-nucleotide exchange factors (Hsu et al., 2007; Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2008; Calderón-Pérez et al., 2014). It must be mentioned that the structures of the P. falciparum and P. knowlesi TCTPs have been experimentally determined (Vedadi et al., 2007; Eichhorn et al., 2013). Although this last activity has not been shown in vitro, it is clear that this domain is important for TCTP function. The P. falciparum TCTP is secreted into its host bloodstream, and can reach high titers, albeit its role in pathogenicity is not clear (MacDonald et al., 2001; Pelleau et al., 2012). Since HRF induces B cell proliferation, we suggested that the P. falciparum TCTP, which also induces histamine release (MacDonald et al., 2001), may mimic such activity, although not as efficiently as its host counterpart (Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2008). We have shown that P. falciparum TCTP induces B cell proliferation at low levels, but shows a different localization pattern when internalized into B cells (Calderón-Pérez et al., 2014), indicating that its structural distortion leads to a novel activity (possibly interfering with the host immune response). Interestingly, the structural variation of Plasmodium TCTPs was also observed in the CmTCTP-like proteins from plants, suggesting also functional variation relative to AtTCTP1-like proteins. Indeed, the pocket region, which is formed almost invariably by glutamic acid residues at positions 12 and 134 and leucine at 74 (using the numbering of residues from the Schizosaccharomyces pombe TCTP as reference) has an “open” conformation in most non-plant TCTPs and AtTCTP1-like proteins, while it displays a “closed” conformation in P. falciparum and P. knowlesi TCTPs, as well as in CmTCTP-like proteins (Figure 4). Interestingly, there are a few extant non-plant TCTP sequences that have substitutions in one of these three conserved residues, but no such substitutions were found in plant sequences. As with the Plasmodium genus, the AtTCTP1-like and CmTCTP-like proteins may display different biological activities, at least in the case of the type members of these groups in Arabidopsis and in pumpkin (Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2013; Toscano-Morales et al., submitted). Indeed, CmTCTP (and, intriguingly, AtTCTP2), but not AtTCTP1 are capable of inducing whole-plant regeneration when harbored by A. rhizogenes (although not by A. tumefaciens, suggesting the involvement of rol genes and/or auxins in this process). It has been shown that AtTCTP1 has a central role in the regulation of cell proliferation, although not postmitotic growth (Berkowitz et al., 2008; Brioudes et al., 2010). This could be extrapolated to all AtTCTP1-like proteins, while CmTCTP-like proteins could have a more direct role in developmental reprogramming.

Figure 4.

Structural comparison between Arabidopsis and Plasmodium falciparum TCTPs. The “pocket” structure (highlighted in dashed red lines) and the flexible loop orientation indicate probable structural differences between these TCTPs. As can be observed, the pocket region of AtTCTP1 and S. pombe TCTP (SpTCTP) have a “closed” conformation, while in CmTCTP and P. falciparum TCTP (PfTCTP) have an “open” conformation, that may cause altered interaction with its potential targets, or with different factors.

The phylogenetic relationship of plant TCTPs showed a large polytomy; thus, it could not be resolved satisfactorily. According to a previous analysis, in the cladogram of plant and non-plant TCTPs, two polytomies were likewise observed within the plant and vertebrate clades. In the case of plants, there were two groups, one of which being highly structured and reflecting the known phylogeny of angiosperms. However, the other group, whose phylogeny was not resolved, included sequences from both dicots and monocots in a polytomy (Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2008). It is generally accepted that phylogenies based on a single gene or protein sequence are prone to artifacts and tend to be inaccurate due to uneven rates of substitution. As shown in this and previous studies, this is the case for TCTP in plants, at least with the sequences used for the phylogenetic analysis. As substitution rates vary among members of the same lineage, as is suggested in plants, the data reinforce possible differential selective pressure on TCTP sequences. We expected that using a TCTP sequence from a phylogenetically distant organism (a red alga, C. merolae) as outgroup to root the tree could reflect the functional similarities between these proteins; nevertheless, phylogenetic relationships could not be established either. Low bootstrap values underscore the high similarity of plant TCTP sequences.

Emergence of CmTCTP-like genes and different role of the corresponding proteins

In general terms, it appears that CmTCTP-like genes could arise roughly during the emergence of land plants through gene duplication of an ancestral AtTCTP1-like gene (which is deduced from the nature of the extant TCTP sequence from C. subellipsoidea). The absence of this gene in most chlorophyte genomes could be due to technical problems, explained if it is located close to centromeres or telomeres, which are regions notoriously difficult to sequence. However, if these genes are really not present, then other proteins must perform the function carried out by TCTP, the nature of which is not clear. The loss of TCTP genes in these lineages cannot be discarded either, but a more thorough analysis of the regions flanking the TCTP gene in C. subellipsoidea and the homologous regions in other chlorophytes may help elucidate this question. In any case, the plant TCTP interactome could help elucidate the pathways regulated by the proteins that replaced them in these species, such as regulation of cell cycle duration and proliferation (Brioudes et al., 2010). In the case of AtTCTP2, it arose recently, before the divergence of the Arabidopsis genus; indeed, the position of the A. lyrata AtTCTP2 homolog in the genome is equivalent to its Arabidopsis counterpart. AtTCTP1 and AtTCTP2 show an identity superior to 80%; the most visible difference is a 13 aa deletion of AtTCTP2 relative to AtTCTP1. No other TCTP harbors such deletion, except Giardia lamblia TCTP. Interestingly, the deletion falls in the same region (the flexible loop) as in AtTCTP2; this loop may be an hypervariable region that in all predicted TCTP structures falls outside of the domains known to be involved in some of its activities (Ca+2 and microtubule binding for example). However, it appears that distortions in such domain may alter the overall conformation of these proteins and hence their function.

The analysis of the predictive 3D conformation shows that it is feasible to infer that there may be a division of the labor among plants harboring multiple TCTP genes, and moreover that in some cases the unique TCTP version could perform several functions. Clearly, experimental evidence must be obtained in order to test this hypothesis; however, this can be done in a straightforward manner; if this is correct, all AtTCTP1-like genes will be unable to regenerate tobacco plants via A. rhizogenes mediated inoculation of leaf explants, in contrast to CmTCTP-like genes (Hinojosa-Moya et al., 2013; Toscano-Morales et al., submitted). Given that the same underlying mechanisms of cell proliferation operate in plants and other eukaryotes, this simple assay could be used to determine whether a TCTP gene is involved in cell proliferation or cell (developmental) reprogramming.

Concluding remarks

The exact mechanism through which TCTP regulates plant growth and development is not clear. The fact that there may be at least two different groups of TCTP genes in plants, one more involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, and the other one in cell reprogramming, was inferred from the activity of two proposed representative members of this protein family in plants, AtTCTP1 and CmTCTP from Arabidopsis and C. maxima, respectively. On the other hand, such differential activity correlates with subtle structural variations of the predicted three-dimensional structures of these proteins. Interestingly, these structural variations are also present in other eukaryotes, which may also correlate with functional variation. We propose that most plant TCTPs fall within one of these groups, and that a simple assay, i.e., regeneration of tobacco when harbored by A. rhizogenes, could help determine a role in cell proliferation alone or cell reprogramming.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work, and that described herein from our group was supported by CONACyT grants No. 105985 and 156162 (to Beatriz Xoconostle-Cázares and Roberto Ruiz-Medrano, respectively) and SENASICA (Beatriz Xoconostle-Cázares, Roberto Ruiz-Medrano). Diego F. Gutiérrez-Galeano, Roberto Toscano-Morales, and Berenice Calderón-Pérez acknowledge doctoral fellowship support from CONACyT Mexico.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fpls.2014.00361/abstract

Protein sequence alignment. The amino acid sequence alignment was performed using the MUSCLE software on plant sequences included in this work.

Phylogenetic analysis of the TCTP in plants. C. maxima translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) sequence (GenBank Accession No. ABC02401) was retrieved form NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and used as query. Protein homologs were identified by BLAST search against the phytozome database (http://phytozome.net). Full-length protein sequences were aligned with MUSCLE (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/muscle). ProtTest program (PROTTEST 2.4, Abascal et al., 2005) was used for the selection of the model of protein evolution that best fitted the set of sequences. Evolutionary analysis was conducted in PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al., 2010) and MEGA5. The evolutionary phylogenetic reconstruction (shown as dendrogram) was inferred using the LG+G evolution method and the following parameters: number of substitution rate categories 4, gamma shape parameter 0.642. Bootstrap values higher than 60% are shown (1000 replicates). The analysis involved 55 amino acid sequences.

Predictive 3D structure comparison of AtTCTP-like proteins. Full-length protein sequences were selected from phytozome database (http://phytozome.net) and refined through a comparison with NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Amino acid sequences were submitted to the automated protein structure homology-modeling program server SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/), this server builds a model for each protein target using as templates homologous protein structures which have been experimentally proved (Arnold et al., 2006; Kiefer et al., 2009). Swiss PDB Viewer application (http://www.expasy.org/spdbv/) was used for visualizing predictive 3D structures (Guex and Peitsch, 1997).

Predictive 3D structure comparison of CmTCTP-like proteins. Full-length protein sequences were selected from phytozome database (http://phytozome.net). Amino acid sequences were submitted to the automated protein structure homology-modeling program server SWISS-MODEL. Swiss PDB Viewer application (http://www.expasy.org/spdbv/) was used for visualizing predictive 3D structures (Guex and Peitsch, 1997).

References

- Abascal F., Zardoya R., Posada D. (2005). ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics 21, 2104–2105 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amson R., Pece S., Marine J. C., Di Fiore P. P., Telerman A. (2013). TPT1/ TCTP-regulated pathways in phenotypic reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol. 23, 37–46 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki K., Suzui N., Fujimaki S., Dohmae N., Yonekura-Sakakibara K., Fujiwara T., et al. (2005). Destination-selective long-distance movement of phloem proteins. Plant Cell 17, 1801–1814 10.1105/tpc.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K., Bordoli L., Kopp J., Schwede T. (2006). The SWISS-MODEL Workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22, 195–201 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Williams N., Misleh C., Li W. W. (2006). MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nuc. Acids Res. 34, W369–W373 10.1093/nar/gkl198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes A., Bale J., Constantinidou C., Ashton P., Jones A., Pritchard J. (2004). Determining protein identity from sieve element sap in Ricinus communis L. by quadrupole time of flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometry. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1473–1481 10.1093/jxb/erh161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz O., Jost R., Pollmann S., Masle J. (2008). Characterization of TCTP, the translationally controlled tumor protein, from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 20, 3430–3447 10.1105/tpc.108.061010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommer U. A., Borovjagin A. V., Greagg M. A., Jeffrey I. W., Russell P., Laing K. G., et al. (2002). The mRNA of the translationally controlled tumor protein P23/TCTP is a highly structured RNA, which activates the dsRNA-dependent protein kinase PKR. RNA 8, 478–496 10.1017/S1355838202022586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommer U. A., Thiele B. J. (2004). The translationally controlled tumour protein (TCTP). Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36, 379–385 10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00213-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brioudes F., Thierry A. M., Chambrier P., Mollereau B., Bendahmane M. (2010). Translationally controlled tumor protein is a conserved mitotic growth integrator in animals and plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 16384–16389 10.1073/pnas.1007926107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Pérez B., Xoconostle-Cázares B., Lira-Carmona R., Hernández-Rivas R., Ortega-López J., Ruiz-Medrano R. (2014). The Plasmodium falciparum translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) is incorporated more efficiently into B cells than its human homologue. PLoS ONE 9:e85514 10.1371/journal.pone.0085514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanella J. J., 1st., Bitincka L., Smalley J. (2003). MatGAT: an application that generates similarity/identity matrices using protein or DNA sequences. BMC Bioinformatics 4:29 10.1186/1471-2105-4-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao B., Lu Y., Chen G., Lei J. (2010). Functional characterization of the translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) gene associated with growth and defense response in cabbage. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 103, 217–226 10.1007/s11240-010-9769-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza C. R., Carvalho L. J., de Mattos C. J. (2004). Comparative gene expression study to identify genes possibly related to storage root formation in cassava. Protein Pept. Lett. 11, 577–582 10.2174/0929866043406319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn T., Winter D., Büchele B., Dirdjaja N., Frank M., Lehmann W. D., et al. (2013). Molecular interaction of artemisinin with translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) of Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem. Pharmacol. 85, 38–45 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolayev V., Weschke W., Manteuffel R. (2003). Comparison of Al-induced gene expression in sensitive and tolerant soybean cultivars. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 2745–2756 10.1093/jxb/erg302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N., Peitsch M. C. (1997). SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723 10.1002/elps.1150181505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Dufayard J. F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. (2010). New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa-Moya J. J., Xoconostle-Cázares B., Lucas W. J., Ruiz-Medrano R. (2006). Differential accumulation of a translationally controlled tumor protein mRNA from Cucurbita maxima in response to CMV infection, in Biology of Plant Microbe Interactions, Vol. 5, eds Sanchez F., Quinto C., Lopez-Lara I. M., Geiger O. (St. Paul, MN: International Society for Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions; ), 242–246 [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa-Moya J., Xoconostle-Cazares B., Piedra-Ibarra E., Mendez-Tenorio A., Lucas W. J, Ruiz-Medrano R. (2008). Phylogenetic and structural analysis of translationally controlled tumor proteins. J. Mol. Evol. 66, 472–483 10.1007/s00239-008-9099-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa-Moya J., Xoconostle-Cázares B., Toscano-Morales R., Ramírez-Ortega F., Cabrera-Ponce J. L., Ruiz-Medrano R. (2013). Characterization of the pumpkin Translationally-Controlled Tumor Protein CmTCTP. Plant Signal. Behav. 8:e26477 10.4161/psb.26477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Y. C., Chern J. J., Cai Y., Liu M., Choi K. W. (2007). Drosophila TCTP is essential for growth and proliferation through regulation odRheb GTPase. Nature 445:785–788 10.1038/nature05528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A. M., Thomas V., Bennett M. H., Mansfield J., Grant M. (2006). Modifications to the Arabidopsis defense proteome occur prior to significant transcriptional change in response to inoculation with Pseudomonas syringae. Plant Physiol. 142, 1603–1620 10.1104/pp.106.086231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer F., Arnold K., Künzli M., Bordoli L., Schwede T. (2009). The SWISS-MODEL Repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D387–D392 10.1093/nar/gkn750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. M., Han Y. J., Hwang O. J., Lee S. S., Shin A. Y., Kim S. Y., et al. (2012). Overexpression of Arabidopsis translationally controlled tumor protein gene AtTCTP enhances drought tolerance with rapid ABA-induced stomatal closure. Mol. Cells 33, 617–626 10.1007/s10059-012-0080-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Deng Z., Liu X., Qin B. (2013). Molecular cloning, expression profiles and characterization of a novel translationally controlled tumor protein in rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). J. Plant Physiol. 170, 497–504 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Liu X. Y., Li X. P., Wang Z. Y. (2010). Cloning of a TCTP Gene in wheat and its expression induced by Erysiphe graminis. Bull. Bot. Res. 30, 441–447 [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A. R., Franco A. P. (2006). Cloning and expression of cDNA encoding translationally controlled tumor protein from strawberry fruits. Biol. Plantarum 50, 447–449 10.1007/s10535-006-0067-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C., Wallis J. G., Browse J. (2007). An analysis of expressed sequence tags of developing castor endosperm using a full-length cDNA library. BMC Plant Biol. 7:42 10.1186/1471-2229-7-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald S. M., Bhisutthibhan J., Shapiro T. A., Rogerson S. J., Taylor T. E., Tembo M., et al. (2001). Immune mimicry in malaria: plasmodium falciparum secretes a functional histamine-releasing factor homolog in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 10829–10832 10.1073/pnas.201191498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano-Ito M., Ichikawa S. (2012). Biological effects of Mammalian translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) on cell death, proliferation, and tumorigenesis. Biochem. Res. Int. 2012:204960 10.1155/2012/204960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakkaew A., Chotigeat W., Phongdara A. (2010). Molecular cloning and expression of EgTCTP, encoding a calcium binding protein, enhances the growth of callus in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis, Jacq). Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 562, 561–569 [Google Scholar]

- Pay A., Heberle-Bors E., Hirt H. (1992). An alfalfa cDNA encodes a protein with homology to translationally controlled human tumor protein. Plant Mol. Biol. 19, 501–503 10.1007/BF00023399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelleau S., Diop S., Dia Badiane M., Vitte J., Beguin P., Nato F., et al. (2012). Enhanced basophil reactivities during severe malaria and their relationship with the Plasmodium falciparum histamine-releasing factor translationally controlled tumor protein. Infect. Immun. 80, 2963–2970 10.1128/IAI.00072-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X., Gao F., Zhang J., Gao J., Lin S., Wang Y., et al. (2011). Embryo formation regulation of the endosperm development Molecular cloning, characterization and expression of cDNA encoding translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) from Jatropha curcas L. Mol. Biol. Rep. 38, 3107–3112 10.1007/s11033-010-9980-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Medina C., Atkins C. A., Mann A. J., Jordan M. E., Smith P. M. C. (2011). Macromolecular composition of phloem exudate from white lupin (Lupinus albus L.). BMC Plant Biology 11:36 10.1186/1471-2229-11-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Medrano R., Xoconostle-Cázares B., Ham B. K., Li G., Lucas W. J. (2011). Vascular expression in Arabidopsis is predicted by the frequency of CT/GA-rich repeats in gene promoters. Plant J. 67, 130–144 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04581.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage-Ono K., Ono M., Harada H., Kamada H. (1998). Dark-induced accumulation of mRNA for a homolog of translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) in Pharbitis. Plant Cell Physiol. 39, 357–360 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Nei M., Kumar S. (2014). Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 11030–11035 10.1073/pnas.0404206101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaw P., Baxter N. J., Hounslow A. M., Price C., Waltho J. P., Craven C. J. (2001). Structure of TCTP reveals unexpected relationship with guanine nucleotide-free chaperones. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 701–704 10.1038/90415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedadi M., Lew J., Artz J., Amani M., Zhao Y., Dong A., et al. (2007). Genome-scale protein expression and structural biology of Plasmodium falciparum and related Apicomplexan organisms. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 151, 100–110 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent D., Ergui A., Bohlman C., Tattersall E., Tillett R., Wheatley M., et al. (2007). Proteomic analysis reveals differences between Vitis vinifera L. cv. Chardonnay and cv. Cabernet Sauvignon and their responses to water deficit and salinity. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 1873–1892 10.1093/jxb/erm012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Shang Y., Yang L., Zhu C. (2012). Comparative proteomic study and functional analysis of translationally controlled tumor protein in rice roots under Hg2+ stress. J. Environ. Sci. 24, 2149–2158 10.1016/S1001-0742(11)61062-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Fonseca B. D., Tang H., Liu R., Elia A., Clemens M. J., et al. (2008). Re-evaluating the roles of proposed modulators of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30482–30492 10.1074/jbc.M803348200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo H. H., Hawes M. C. (1997). Cloning of genes whose expression is correlated with mitosis and localized in dividing cells in root caps of Pisum sativum L. Plant Mol. Biol. 35, 1045–1051 10.1023/A:1005930625920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Protein sequence alignment. The amino acid sequence alignment was performed using the MUSCLE software on plant sequences included in this work.

Phylogenetic analysis of the TCTP in plants. C. maxima translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) sequence (GenBank Accession No. ABC02401) was retrieved form NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and used as query. Protein homologs were identified by BLAST search against the phytozome database (http://phytozome.net). Full-length protein sequences were aligned with MUSCLE (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/muscle). ProtTest program (PROTTEST 2.4, Abascal et al., 2005) was used for the selection of the model of protein evolution that best fitted the set of sequences. Evolutionary analysis was conducted in PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al., 2010) and MEGA5. The evolutionary phylogenetic reconstruction (shown as dendrogram) was inferred using the LG+G evolution method and the following parameters: number of substitution rate categories 4, gamma shape parameter 0.642. Bootstrap values higher than 60% are shown (1000 replicates). The analysis involved 55 amino acid sequences.

Predictive 3D structure comparison of AtTCTP-like proteins. Full-length protein sequences were selected from phytozome database (http://phytozome.net) and refined through a comparison with NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Amino acid sequences were submitted to the automated protein structure homology-modeling program server SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/), this server builds a model for each protein target using as templates homologous protein structures which have been experimentally proved (Arnold et al., 2006; Kiefer et al., 2009). Swiss PDB Viewer application (http://www.expasy.org/spdbv/) was used for visualizing predictive 3D structures (Guex and Peitsch, 1997).

Predictive 3D structure comparison of CmTCTP-like proteins. Full-length protein sequences were selected from phytozome database (http://phytozome.net). Amino acid sequences were submitted to the automated protein structure homology-modeling program server SWISS-MODEL. Swiss PDB Viewer application (http://www.expasy.org/spdbv/) was used for visualizing predictive 3D structures (Guex and Peitsch, 1997).