Abstract

The second messengers cAMP and cGMP exist in multiple discrete compartments and regulate a variety of biological processes in the heart. The cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases, by catalyzing the hydrolysis of cAMP and cGMP, play crucial roles in controlling the amplitude, duration, and compartmentalization of cyclic nucleotide signaling. Over 60 phosphodiesterase isoforms, grouped into 11 families, have been discovered to date. In the heart, both cAMP- and cGMP-hydrolyzing phosphodiesterases play important roles in physiology and pathology. At least 7 of the 11 phosphodiesterase family members appear to be expressed in the myocardium, and evidence supports phosphodiesterase involvement in regulation of many processes important for normal cardiac function including pacemaking and contractility, as well as many pathological processes including remodeling and myocyte apoptosis. Pharmacological inhibitors for a number of phosphodiesterase families have also been used clinically or preclinically to treat several types of cardiovascular disease. In addition, phosphodiesterase inhibitors are also being considered for treatment of many forms of disease outside the cardiovascular system, raising the possibility of cardiovascular side effects of such agents. This review will discuss the roles of phosphodiesterases in the heart, in terms of expression patterns, regulation, and involvement in physiological and pathological functions. Additionally, the cardiac effects of various phosphodiesterase inhibitors, both potentially beneficial and detrimental, will be discussed.

Keywords: cAMP, cGMP, PDE, heart

Introduction

Cyclic nucleotide signaling mediated by adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP) or cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cGMP), is a critical signal transduction process in various cell types. Generally speaking, an internal or external stimulus causes production of the second messengers cAMP or cGMP, which then activate downstream effector molecules, producing a biological response. In the cardiomyocyte, a number of processes, from contractility to cell survival, are regulated by cAMP or cGMP. In many cases, cAMP and cGMP, and their major respective effector enzymes, protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase G (PKG/CGK), act in a somewhat antagonistic manner. For example, cAMP/PKA signaling potentiates β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR)-induced myocardial contractility, while cGMP/PKG inhibits the same effect. Chronic cAMP/PKA activation may also increase cardiomyocyte apoptosis [1], while chronic cGMP/PKG activation can increase cell survival [2].

cAMP is produced by the adenylyl cyclase (AC) proteins, of which 10 isoforms, including 9 membrane bound and 1 cytosolic, have been discovered to date [3]; AC4, 5, 6, 7, and soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC) [4], are known to be expressed in cardiomyocytes [5]. ACs can be activated by a number of effector molecules, primarily including the catecholamine/β-adrenergic receptor system, as well as the prostaglandin receptors [5], the relaxin receptors [6], and myriad others. Downstream effectors of cAMP in the myocardium include, most notably, PKA [7], as well as exchange protein activated by cAMP (Epac) [8], and cyclic nucleotide gated channels (CNGs) in the pacemaking regions of the heart [8].

cGMP is produced by 2 types of guanylyl cyclase in the myocardium: soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) and particular guanylyl cyclase (pGC), coupled to unique signaling pathways. sGCs are cytosolic proteins and are activated by nitric oxide (NO). pGCs, also known as natriuretic peptide receptors, are membrane bound and activated by direct binding of natriuretic peptides, including either atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), or C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) [9]. The primary downstream effectors of cGMP in the myocardium are the cGMP-activated protein kinase PKG as well as certain phosphodiesterases which can be activated or inhibited by cGMP [9].

The involvement of the cyclic nucleotides in myriad cellular processes implies the existence of distinct “pools” of cAMP and cGMP involved in regulation of specific processes. For instance, NO and ANP/BNP appear to activate spatially distinct cGMP pools in the cardiomyocyte [9,10], and considerable evidence supports the existence of spatially distinct cAMP pools as well [7]. The cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (PDEs) are a class of proteins, which catalyze the hydrolysis of cAMP and cGMP into 5′-AMP and 5′-GMP, respectively. By hydrolyzing cyclic nucleotides, PDEs are responsible not only for halting cyclic nucleotide signal transduction-based signaling, but for preventing diffusion of cyclic nucleotides beyond their site of production, maintaining these distinct pools. PDEs therefore regulate cyclic nucleotide signaling both spatially and temporally, and unsurprisingly, specific PDEs have been found localized to distinct regions of the cardiomyocyte, often in signaling complexes with cyclases, ion channels, kinases, and scaffolding proteins [11]. The PDE proteins are grouped into 11 families, PDE1–PDE11, by substrate preference, sequence homology, modes of regulation, kinetics, and pharmacological properties [12]. In total, over 60 mammalian PDE isoforms have been described within these families. Of the PDE families, PDE1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, and 9 are reported in the myocardium. PDE1, 2, and 3 hydrolyze both cAMP and cGMP, PDE 4 and 8 hydrolyze cAMP exclusively, and PDE5 and 9 hydrolyze cGMP exclusively at physiological substrate levels.

Dysregulation of cyclic nucleotide signaling has been shown to play a significant role in many types of cardiovascular disease. Alterations in PDE expression or activity are responsible for the disruption of cyclic nucleotide homeostasis, contributing to disease progression. Unfortunately, PDE inhibition as a method of treating cardiac diseases has had mixed results. Recent data suggest that inhibition of certain PDEs such as PDE5 may hold promise for preventing or even reversing cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction; however, inhibition of other PDEs such as PDE3 has been associated with increased cardiac cell death and development of arrythmias. This review will present an overview of the roles of the PDEs in cardiac biology and disease.

PDE Isozymes in the Heart

PDE1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, and 9 have been reported to be expressed in the heart. Of these families, all but PDE9 have a role in cardiac physiology and/or pathology [2,13]. Each PDE family has a unique expression pattern and enzymatic characteristics, which contribute to its roles in the cardiomyocyte.

The PDE1 family of phosphodiesterases is also known as the Ca2+/calmodulin stimulated PDEs, and is comprised of 3 genes, PDE1A, PDE1B, and PDE1C, with multiple splice variants for each gene, generally expressed in a cell-specific or tissue-specific manner. All PDE1 enzymes possess a calmodulin binding region, and their activities can be stimulated up to 10-fold in response to Ca2+/CaM binding [14]. Sensitivity to Ca2+, however, is different among variants [15]. As such, PDE1 family members are thought to act as signal integrators between calcium and cyclic nucleotide signaling pathways [14,16]. All PDE1 enzymes are able to hydrolyze both cAMP and cGMP in vitro, although with different kinetic properties. PDE1A and PDE1B have been shown to hydrolyze cGMP with significantly greater affinity than cAMP, while PDE1C hydrolyzes both cAMP and cGMP with similar affinity. Inside of cells, PDE1A primarily regulates cellular cGMP levels in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and cardiac myocytes [17,18]. In cardiac fibroblasts, PDE1A appears to regulate both cGMP and cAMP [19]. PDE1B has been shown to predominantly regulate cGMP levels in macrophages [20], and also appears to play a role in regulating cAMP levels in certain types of cells [21,22]. PDE1C has the highest affinity for cAMP, and appears to regulate cellular cAMP in multiple cell types, including VSMCs [23], βTC3 insulinoma cells, pancreatic islet cells [24], and A172 glioblastoma cells [25]. A role for PDE1C in regulating cellular cGMP has not yet been reported, but there is little reason to believe it cannot do so. In humans, multiple studies have reported that PDE1 accounts for a significant portion of cGMP-hydrolytic activity in the myocardium, although which gene(s) were responsible was not established [26,27]. Of the 3 PDE1 genes, only PDE1A and 1C have been detected in the myocardium. However, the relative expression of these genes differs significantly by species. PDE1A is expressed in the heart of human, rat, and mouse [17,28], while PDE1C can be detected in human and mouse, but not rat myocardial tissue [14,17]. In addition, PDE1C has also been reported to localize along M and Z-lines in human cardiac myocytes [27].

PDE2, the cGMP-stimulated PDE, is a dual substrate phosphodiesterase, able to hydrolyze cAMP and cGMP with high affinity. PDE2 members contain an N-terminal GAF domain to which cGMP can bind, increasing catalytic activity by up to 30-fold [29]. One variant, PDE2A, is known to be present in the myocardium, and is associated primarily with the plasma membrane as well as the Golgi, sarcoplasmic reticulum, and the nuclear envelope [29]. In the heart, PDE2 is thought to act primarily as a signal integrator between cGMP and cAMP signaling, allowing reduction in cAMP levels in response to cGMP production. Most studies support the notion that PDE2 is responsible for only a small fraction of total cAMP hydrolyzing activity in the myocardium [29,30]; however, as will be described later in this review, in the presence of cGMP, PDE2 can play an important role in regulating certain cAMP pools. In addition to its role in cAMP signaling, PDE2 appears to help maintain localization of cGMP in the cardiomyocyte. Specifically, PDE2 plays a minor role in the hydrolysis of sGC-produced cGMP, and a more significant role in hydrolysis of pGC-produced cGMP [10]. The functional implications of PDE2-mediated control of cardiac cGMP have yet to be established.

PDE3 is known as the cGMP-inhibited phosphodiesterase. It is a dual-substrate phosphodiesterase; however, it hydrolyzes cGMP with a much lower Vmax than cAMP, so cGMP effectively acts as an inhibitor of cAMP hydrolysis. PDE3 has 2 genes, PDE3A and PDE3B, and acts primarily to regulate cAMP levels in cells. PDE3 regulation of cellular cAMP can modulate a number of phenomena, from cardiomyocyte contractility [31] to lipolysis in adipose tissue [32]. PDE3A is abundant in platelets, cardiomyocytes and VSMCs [33], while PDE3B is abundant in adipocytes, pancreatic cells, and hepatocytes [34]. Recently, PDE3B has also been described in cardiomyocytes [31] although PDE3A appears to represent the dominant isoform [31]. In ventricular cardiomyocytes of mice, PDE3 activity can be detected in both the particulate and soluble fractions of the cell.

PDE4 is a cAMP-specific PDE. Four different PDE4 genes exist, PDE4A–PDE4D, with over 20 isoforms of these genes recorded to date. PDE4A, 4B, and 4D have been detected in the heart [35]. It appears that PDE4 is responsible for a significant portion of cAMP hydrolysis in the rodent myocardium. For example, when using 1 μM cAMP as a substrate, approximately 50–60 % and 30 % of total cAMP-hydrolyzing activity has been attributed to PDE4 in rat and mouse heart tissue, respectively [36–38]. By contrast, PDE4 represents a much smaller portion of total cAMP-hydrolyzing activity in human heart (<10 %), apparently due to higher non-PDE4 PDE activity [37]. However, given the differing Km’s and Vmax’s of various PDE isoforms, this balance can probably change quite significantly at different cAMP concentrations.

PDE5 hydrolyzes cGMP exclusively, and is activated by cGMP binding to its GAF domain, hence it is known as the cGMP-activated and cGMP-specific PDE. PDE5 consists of a single gene, PDE5A. Among its 3 isoforms PDE5A1, 5A2 and 5A3, PDE5A1 and 5A2 have been detected in the heart [39]. Very low expression levels of PDE5 have been reported in healthy cardiac tissue in mice [40] and humans [26,41]. However, PDE5 appears to be upregulated in the diseased heart [40,42]. In murine cardiomyocytes, PDE5 has been found in Z-bands via immunofluorescent and electron microscopic analyses [43], although the specificity of the PDE5 antibody used in this study deserves further verification. The function of PDE5 in cardiomyocytes has also been demonstrated by shRNA-mediated PDE5 knockdown in isolated cardiomyocytes [44] as well as transgenic mice with myocyte-specific PDE5A overexpression [44]. Nonetheless, development of a PDE5A knockout mouse would be desirable. PDE5 expression has also been reported in cardiac fibroblasts in mouse [45]. The PDE8 family is highly specific for cAMP, and is unique amongst the PDE families for its insensitivity to the general PDE inhibitor IBMX. PDE8 has 2 genes, PDE8A and 8B. PDE8A was recently shown to be expressed in mouse ventricular myocytes where it apparently alters Ca2+ handling [46].

PDE9 is a cGMP-hydrolyzing PDE, with the highest affinity for cGMP of any PDE characterized to date [2]. While its expression within the human heart tissue has been detected on the mRNA level [47], little data exists on the functional role of PDE9 in the heart [2].

PDEs and Pacemaking Activity

PDE3 and PDE4 have been shown to regulate the basal pacemaking activity of the sino-atrial (SA) node of the heart [47, 48]. cAMP increases SA node pacemaking activity, through both PKA-dependent and independent mechanisms. PKA-mediated phosphorylation of K+ channels and L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCCs) directly increases current flux [49]. Phosphorylation of cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2) and phospholamban (PLB) increases Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), which indirectly generates an inward current via activation of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger NCX and subsequently promotes depolarization of cardiomyocytes in the SA node. Additionally, cAMP can directly activate pacemaker hyperpolarization and cyclic nucleotide-activated (HCN) channels [50,51], increasing heart rate. By controlling cellular cAMP concentrations, cAMP-hydrolyzing phosphodiesterases control basal SA-node pacemaking activity. PDE3 and PDE4 appear to be the 2 families of PDE responsible for this effect, although the particular isoforms responsible for the effect may vary by species. For example, the SA pacemaking activity is controlled by both PDE3 and PDE4 in mouse and piglet [52,53] while in rat, it is exclusively controlled by PDE4 [48,54]. While PDE3 and PDE4 have important roles in controlling basal pacemaking activity in the SA node, they appear to have little control over catecholamine-induced increases in pacemaking frequency. Multiple studies have demonstrated that inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 in the SA node does not potentiate catecholamine-induced chronotropic effects in various species [48,52–54]. This implies that SA node cells contain 2 cAMP compartments, one involved in basal heart rate, modulated by PDE3/PDE4, and another involved in catecholamine-induced inotropy, but not coupled to PDE3 and PDE4.

PDEs and Ca 2+ Handling/Cardiac Contractility

As previously mentioned, cAMP elevation upon β-AR stimulation activates PKA, which subsequently phosphorylates and activates multiple substrates that influence contraction/relaxation of cardiomyocytes by regulating Ca2+ transients and contractile protein phosphorylation. These include LTCCs in the sarcolemma, cardiac RyR2 and PLB in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), the Ca2+-ATPase SERCA2 in the SR, which is involved in Ca2+ reuptake, and the contractile proteins troponin I (TnI) and troponin C (TnC) [55,56]. Phosphorylation of LTCC by PKA increases Ca2+ influx into cells. PKA phosphorylation activates RyR2, which plays a central role in calcium-induced calcium release and is responsible for a large amount of Ca2+ release from SR stores. Phosphorylation of PLB by PKA accelerates Ca2+ sequestration through SERCA2 into the SR, resulting in more rapid cardiac relaxation. PKA-mediated phosphorylation of TnI and TnC reduces myofilament sensitivity to Ca2+ during relaxation [56]. Furthermore, PKA phosphorylates protein phosphatase inhibitor-1, increasing its ability to inhibit protein phosphatase 1 (PP1). Since PP1 dephosphorylates a number of targets of PKA, including RyR2 and other proteins involved in EC coupling, this effectively potentiates PKA signaling [57]. Thus, PKA is a critical mediator of the positive inotropic effect of β-AR stimulation. By contrast, nitric oxide (NO)-mediated cGMP/PKG signaling negatively regulates cardiac contractility. PKG phosphorylates troponin I, densensitizing it to Ca2+ and reducing contractility [58] and PKG can also phosphorylate and inhibit LTCCs, reducing Ca2+ influx during EC coupling [59]. Interestingly, while both PKA and PKG can phosphorylate LTCCs at a common site on its α subunit, PKG also appears to phosphorylate these channels at a unique site on their β subunits, reducing ICa,L [59]. Several PDEs have been shown to regulate cardiac contractility through modulation of cAMP or cGMP signaling, which will be elaborated on in the following section.

PDE2 has also been reported to regulate myocardial contractile function; however, most experimental evidence comes only from isolated cardiomyocytes or myocardial tissue. For example, PDE2 is responsible for NO-mediated reduction of isoproterenol (Iso)-induced LTCC activity (ICa,L) in frog ventricular myocytes [60] and cGMP-induced reduction of basal ICa,L in human atrial myocytes [61]. In these cell types, cGMP production activates PDE2, causing a reduction in cAMP levels and subsequent reduction in cAMP-induced ICa activity. However, in ventricular myocytes isolated from rat [62], guinea pig and human [63], NO/cGMP-mediated inhibition of Iso-induced LTCC activity appears to be attributable to activation of PKG, rather than PDE2. Low doses of cGMP also increase basal ICa,L in human atrial myocytes due to inhibition of PDE3 [64]. This indicates that not only do significant differences exist in the cGMP-mediated contractile response between species, but also in regions of the heart within species. In rat ventricular myocytes, PDE2 is also responsible for negative regulation of β1 and β2 AR-induced cAMP production and contractility, likely via β3-AR mediated activation of eNOS signaling [65]. In these cells, activation of β3 -AR is thought to lead to production of nitric oxide, leading to activation of sGC and cGMP production. This cGMP then activates PDE2, promoting the degradation of cAMP produced by β1/β2 AR stimulation [65].

PDE3 is the best-known PDE in regulating cardiac contractility, particularly due to the significant inotropic effect of PDE3 inhibitors in laboratory animals as well as in humans. PDE3 inhibition causes increased SR Ca2+ uptake, presumably through PKA-mediated phosphorylation of PLB and RYR2 as well as SERCA activation but does not appear to regulate LTCC channel activity [55,66]. Thus, PDE3 regulation of contractility appears to be primarily through modification of SR-associated, but not plasma membrane-associated, Ca2+ signaling. Pharmacological inhibition of PDE3 in humans causes an increase in heart rate and contractile force, coupled to cAMP-mediated vasodilation in the vasculature and a decrease in peripheral resistance. These effects together cause an increase of cardiac function and coronary blood flow, which is beneficial to patients with congestive heart failure [67], at least initially. The specific PDE3 isoform responsible for the inotropic and chronotropic effects had not been well characterized until the recent development of PDE3A and PDE3B deficient mice, which implicated PDE3A as the dominant isoform regulating contractility. For example, the basal heart rate is significantly increased in PDE3A but not PDE3B KO mice, and the increase in heart rate and cardiac contractility induced by the PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide is also diminished in PDE3A but not PDE3B KO mice [31]. Although PDE3B appears to represent the minority of cardiac PDE3 activity, it has been shown that PDE3B constitutively associates with the PI3Kγ complex in mouse heart, which is essential for the PDE3B activity in the signaling complex [68]. Through a kinase-independent mechanism, PI3Kγ controls PDE3B-mediated cAMP degradation and subsequently modulates cardiac contractility, and protects against pressure overload-induced cardiac damage [68]. However, a different study has shown that PI3Kγ is required for PDE4, not PDE3 activity in a subcellular compartment containing the SR Ca2+-ATPase [66]. These results suggest that PI3Kγ may associate with different PDE isoforms in distinct subcellular microdomains.

PDE4 isozymes also appear to associate with and regulate various EC coupling molecules, particularly in rodents. For example, various PDE4D isozymes form signaling complexes with β1- and β2-AR receptors [69–71], and are involved in termination of β-AR mediated signaling. Other studies have reported functional associations between PDE4 isoforms and RyR2 [72] and SERCA2 [73]. One study specifically showed that the PDE4D3 isoform associates with RyR2, which is critical for regulation of the PKA phosphorylation status of RyR2 [72]. PDE4D deficiency caused RyR2 hyperphosphorylation by PKA, leading to Ca2+ leakage [72]. However, a recent study failed to detect a physical and functional relationship between RyR2 and PDE4D [73]. Instead, this study reported that PDE4D associates with SERCA2-PLB in SR and regulates SR Ca2+ uptake [73]. Given the disparity of some results between these studies, further studies investigating the specific role of PDE4D in cardiac function would be desirable. In addition, PDE4B was shown to couple to LTCCs in mouse heart [38]. Given that PDE4B−/− cardiomyocytes displayed no change in basal ICa,L but a significant increase in isoproterenol-induced ICa,L [38], PDE4B appears to specifically regulate β-AR-stimulated ICa,L.

Recent studies using PDE5 inhibitors also show that PDE5 may play a role in regulation of cardiac contractility. For example, the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil attenuates the β-adrenergic-mediated increase in contractile response in murine [74] and human [75] heart. Furthermore, this regulation of contractility appears to be dependent on the eNOS-mediated localization of PDE5 to the Z-line [43], and is NOS3 and PKG dependent [76]. Of course, the precise role of PDE5 in regulating cardiac contractile function requires further characterization with genetically manipulated PDE5 animals, given that other PDEs might be affected by the relative high doses of sildenafil used in these experiments.

PDE8 was recently characterized in the heart using PDE8A deficient mice [46]. In isolated mouse cardiomyocytes, PDE8A−/− cells display an increase in Iso-induced Ca2+ transient, which is at least partially attributed to increased LTCC ICa,L [46]. In addition, the frequency of Ca2+ sparks under the basal state was higher in PDE8A−/− than in WT myocytes. However, isoproterenol stimulation increased Ca2+ spark frequency to similar levels in both geneotypes, and SR Ca2+ levels are similar between PDE8A−/− and WT myocytes in basal conditions [46]. This suggests that PDE8A may regulate basal but not β-AR stimulated RyR2 activity, and implies that while PDE8A deficiency causes increased RyR2 leakage, it also may cause more rapid SR refilling. The molecular mechanism underlying PDE8A regulated Ca2+ handling needs to be further characterized.

Regulation and Function of PDEs in Pathological Cardiac Remodeling and Dysfunction

In addition to acutely modulating myocyte contractile function, cAMP and cGMP also chronically regulate myocyte gene expression, which leads to pathological cardiac remodeling and subsequent cardiac dysfunction. Pathological cardiac remodeling is associated with myocyte hypertrophy and apoptosis, fibroblast activation and proliferation, and extracellular matrix (ECM) production and deposition. Several of the phosphodiesterases appear to be implicated in this process, presenting multiple possibilities for pharmacological intervention.

PDE1A expression was found to be upregulated in multiple models of cardiac disease, including mouse hearts subjected to chronic b-AR stimulation, chronic pressure overload, and myocardial infarction [17], in rat hearts subjected to chronic angiotensin II infusion [17,36], as well as in human failing hearts [17]. Based on immunostaining analyses, PDE1A induction in the diseased heart occurs in both cardiomyocytes [17] and activated fibroblasts in fibrotic areas of failing hearts [19]. Using cultured neonatal and adult rat cardiomyocytes, PDE1A was shown to be critical in promoting myocyte hypertrophic growth because PDE1 inhibition or PDE1A knockdown significantly attenuated myocyte hypertropy [17]. In cardiac fibroblasts, PDE1A is important for fibroblast transformation to active myofibroblasts and for production of various ECM proteins [19].

PDE1C is also expressed in cardiomyocytes [27]; however, its expression and regulation in diseased hearts, and its physiological function in the heart, are still unclear. In a mouse model of chronic ISO infusion, treatment with the PDE1-selective inhibitor IC86340 significantly attenuated ISO-stimulated cardiac hypertrophy, including decreased global heart weight and myocyte size as well as reduced fibroblast activation and fibrosis [17,19]. This finding suggests that inhibition of PDE1 might represent a useful therapeutic strategy to prevent pathological cardiac remodeling. Further studies, particularly involving genetically manipulated PDE1A and PDE1C mice, will be necessary to understand the exact function of PDE1A and PDE1C in cardiac biology and disease in vivo.

PDE3A appears to be a critical regulator of cardiomyocyte survival. It has been shown that chronic PDE3 inhibition or PDE3A knockdown promotes cardiomyocyte apoptosis via activation of the transcriptional repressor protein ICER (inducible cAMP early repressor) [1]. ICER activation causes downregulation of CREB-mediated transcription, including of antiapoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2, leading to apoptosis [77]. Downregulation of PDE3A expression and upregulation of ICER are indeed found in tissue from various animal models of heart disease and from humans hearts with ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathies [77–80]. Interestingly, when cardiac function is improved by overexpression of a constitutively active form of mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (CA-MEK5α) or using the angiotensin receptor antagonist valsartan, PDE3A and ICER levels are restored [79,81]. Valsartan treatment also reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improves hemodynamics in mice after myocardial infarction [81]. Taken together, these results suggest that reduction of PDE3A and induction of ICER might contribute to the pathogenesis of heart failure and may also provide an explanation for the detrimental effects associated with chronic PDE3 inhibitor therapy in humans.

In experimental animals, pharmacologic inhibition of PDE4 has been shown to potentiate cardiac arrhythmias induced by adrenergic stimulation [52], exercise [65], or myocardial ischemia/reperfusion [82]. Genetic depletion of PDE4D in mice results in delayed after depolarization formation, exercise induced arrhythmias, and sudden death [83,84]. In addition, PDE4D−/− mice develop a late-onset cardiomyopathy and have a significantly increased mortality following myocardial infarction [72]. The underlying mechanism of this effect is likely attributed to RyR2 hyperphosphorylation and malfunction due to the depletion of PDE4D that normally associates with the RyR2 complex and regulates PKA-mediated phosphorylation of RyR2 [72]. Indeed, in human failing hearts, PDE4D levels in RyR2-based complexes are significantly decreased and PKA-dependent RyR2 phosphorylation is significantly increased [72,85]. Furthermore, PDE4B appears to act as a critical regulator of LTCC during β-AR stimulation. Depletion of PDE4B is associated with an increased incidence of burst-pacing induced ventricular arrythmias and tachycardia in the presence of β-AR stimulation in PDE4B−/− mice compared to wild type mice, likely due to increased ICa,L [38]. These results suggest that chronic inhibition or depletion of PDE4 activity may have detrimental effects in rodent hearts. Although experimental evidence strongly supports the importance of PDE4 activity in rodent hearts, pharmacological effects of PDE4 inhibition in the human heart might be different. For example, a recent study reported that a large fraction of cAMP-PDE activity is attributed to PDE4 in the mouse heart, while PDE4 activity is only a minor portion of cAMP-PDE activity in the left ventricle of human heart [37], although this may vary with substrate concentration. This discrepancy may explain the different effects of PDE4 inhibition in the human vs. rodent heart. Interestingly, a recent study indicated that PDE4, particularly PDE4D, appears to represent a significant portion of cAMP-hydrolyzing activity in human atrial tissue, and plays an important role in regulating iso-induced cAMP production. Additionally, administration of the PDE4 inhibitor rolipram to isolated human atrial trabeculae increased incidence of both β1 and β2 induced arrhythmia, and PDE4 activity was also found to be reduced in patients with atrial fibrillation [86]. Thus, this study suggests a critical role of PDE4D downregulation or inhibition in human atrium arrhythmia. Nevertheless, the role of PDE4 in the human heart needs to be further evaluated in the intact heart in vivo.

Although PDE5 has very low basal expression in cardiomyocytes of the normal heart [45,87], PDE5 is significantly upregulated in human [40,87] and murine failing hearts [87], implying a possible role in the development of cardiac pathology. The role of PDE5 in the heart was initially explored with the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil. For example, it has been shown that sildenafil treatment reduced apoptosis and improved ventricular function in various model of cardiac injury and dysfunction such as acute ischemia-reperfusion models in mice and rabbits [88] as well as in a doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity model in mouse [89]. Furthermore, in a TAC-induced hypertrophy/heart failure model in mouse, sildenafil significantly attenuated development of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and improved cardiac function [90]. Sildenafil treatment has also been shown to suppress pro-hypertrophic gene expression and apoptosis and necrosis in adult cardiac myocytes [91,92]. Fibroblast PDE5 could also potentially play a role in the antihypertrophic effects of PDE5 inhibition. Indeed, treatment with the PDE5 inhibitor zaprinast in combination with ANP treatment has previously been shown to reduce procollagen synthesis in rat and human cardiac fibroblasts [93]. However, zaprinast can also inhibit PDE1, and PDE1A is also known to modulate fibroblast activation [19].

It has been proposed that the antihypertrophic effect of sildenafil may involve inhibition of other PDEs in the heart, such as PDE1, at high concentrations of drug. However, several studies have used molecular tools to specifically change PDE5A expression in vitro and/or in vivo. For example, a study involving silencing of PDE5 expression in neonatal rat myocytes specifically detected PDE5 staining in these cells, and showed that PDE5 knockdown or inhibition attenuates hypertrophy in phenylephrine treated neonatal rat myocytes [44]. Given the potential differences between neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes, however, further studies demonstrating the role of PDE5A in modulating hypertrophy in adult cardiomyocytes would be desirable. Cardiac-specific overexpression of PDE5A in mice also worsened TAC-induced cardiac remodeling and dysfunction [40,94]. These observations suggest that induction of PDE5A might be critical in pathological cardiac remodeling and heart failure. Considering that ectopic effects could potentially be associated with PDE5A overexpression, the precise role of PDE5A in cardiac diseases needs to be further confirmed using PDE5A deficient mice. The mechanism of sildenafil’s cardioprotective effects has also been investigated. Several studies have demonstrated a central role for PKG activation [95], particularly through PKG-mediated targeting of regulator of G protein signaling 2 (RGS2) that modulates Gαq-mediated signaling and β2-AR signaling [96,97]. However, a recent in vivo study using mice with either a global PKG knockout, or a global knockout with smooth-muscle specific rescue had no significant differences in cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction induced by TAC or iso-infusion [45]. These findings brought into question the role of PKG in regulating cardiac hypertrophy. Interestingly, another study, using a different line of mice with a cardiac-specific PKG deletion achieved using the Cre/loxP system, did find that PKG deficiency worsened cardiac function and increased fibrosis in multiple mouse models of hypertrophy [98]. The disparity between these models could be due differences in the animal models used, or differences in techniques used to induce cardiac hypertrophy, as there were some differences in methodology in both TAC and iso-infusion between the 2 studies. Therefore, the role of cardiac PKG in sildenafil-mediated antihypertrophic effects remains unclear, and certainly deserves further investigation in the future.

Clinical Use of PDE Inhibitors

Inhibition of PDE3 activity elevates cAMP in cardiac muscle and subsequently increases the rate and magnitude of developed force as well as the rate of muscle relaxation. Concurrently, in vascular smooth muscle, elevated cAMP levels via PDE3 inhibition reduces total peripheral resistance, enhances coronary blood flow, reduces pulmonary vascular resistance, and reduces right atrial pressure (due to venodilation). Thus, PDE3 inhibitors such as milrinone, amrinone, and enoximone have become powerful drugs for the acute treatment of the congestive heart failure, due to their inotropic and vasodilatory actions [99,100]. However, in long-term clinical trials of PDE3 inhibitors, these hemodynamic improvements are typically not sustained, and increased mortality due to arrhythmias and sudden death has been reported [67,101,102]. For this reason, PDE3 inhibitors are only used in certain situations, including as an acute therapy in severe heart failure patients who do not adequately respond to other standard therapy [103], or as a longterm agent, delivered intravenously, in patients awaiting heart transplant [103,104]. Milrinone treatment requires that patients be closely monitored for ventricular arrhythmias or ventricular dysfunction [105]. The detrimental effect of PDE3 inhibitor treatment in patients may be explained by the pro-apoptotic effect of PDE3A inhibition [77]. Experimental and clinical evidence suggests that a short-term increase of PDE3-regulated cAMP is beneficial to patients with heart failure whose contractility is impaired, but a long-term increase of this cAMP is harmful. It is worth noting that another PDE3 inhibitor cilostazol (Pletal) has been used for the treatment of intermittent claudication and related indications for decades [106]. The therapeutic effects of cilostazol are largely attributed to its vasodilatory and antiplatelet actions, mainly due to the inhibition of PDE3 and subsequent elevation of intracellular cAMP levels [107]. Cilostazol is also able to inhibit adenosine uptake at a concentration (≈ 7 μM) similar to that for PDE3 inhibition (≈ 2.7 μM) [107]. This may distinguish cilostazol from other PDE3 inhibitors. For example, elevated interstitial and circulating adenosine, resulting from inhibition of adenosine uptake, potentiates the cAMP effects observed from PDE3 inhibition in smooth muscle and platelets, while it antagonizes the effects of PDE3 inhibition in the heart [108,109]. Thus, the cardiac effects of PDE3 inhibition by cilostazol are significantly minimized compared to other PDE3 inhibitors such as milrinone. Given the differential cardiac effects of PDE3A and PDE3B discussed earlier and the differential effects of PDE3A and 3B in other tissues, development of PDE3A and 3B-specific inhibitors would be useful.

The PDE5 inhibitors sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil, have been used clinically to treat erectile dysfunction [110]. More recently, sildenafil, as Revatio, and tadalafil, as Adcirca, have also been approved for treating pulmonary arterial hypertension [111]. The cardioprotective effects of sildenafil observed in animal studies have led to considerable interest in clinical use of sildenafil to treat heart failure. Recently, a smaller clinical trial involving 45 patients with Stage III heart failure (either ischemic, idiopathic, or hypertensive cardiomyopathy) for a year, found a significant improvement in cardiac function and exercise performance in sildenafil treated patients as well as some indication of reverse remodeling [112]. Another recent study found that 3 months of treatment with sildenafil significantly improves several parameters of cardiac performance and may cause reverse remodeling in patients with nonischemic, nonfailing diabetic cardiomyopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus [113]. A large scale clinical trial sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, RELAX, is currently ongoing to test the effects of sildenafil administration on cardiac and pulmonary function in approximately 200 elderly patients with diastolic heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00763867). Additionally, several studies suggest that sildenafil treatment modestly improves coronary flow reserve in humans with severely stenosed arteries [114] or certain types of coronary artery disease [115]. The effects of sildenafil on coronary blood flow and pulmonary vasculature may indirectly improve cardiac structural remodeling and function.

Conclusions

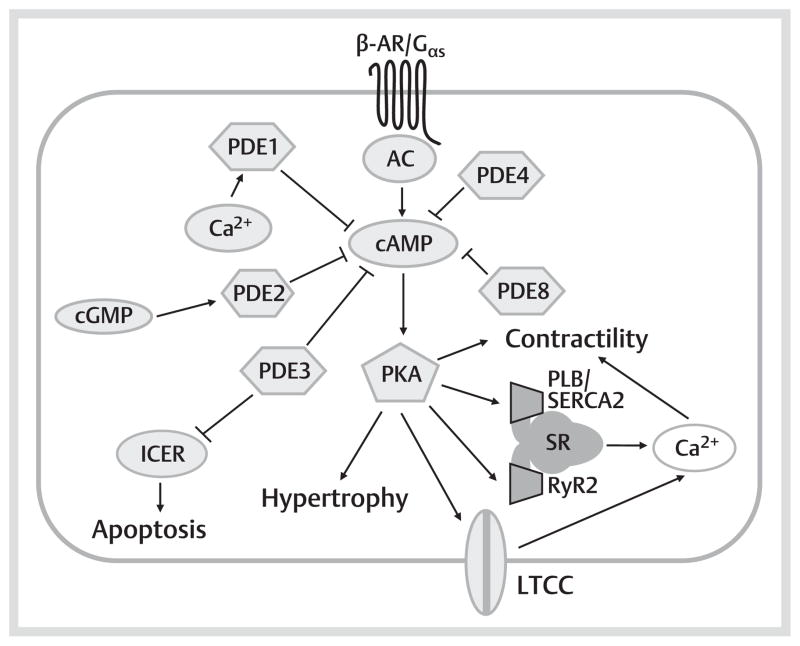

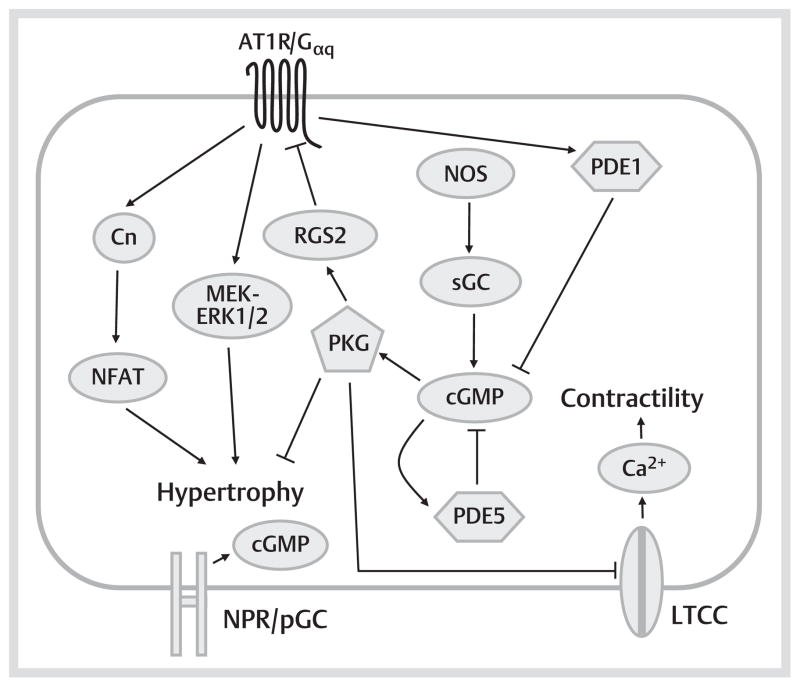

Cyclic nucleotide signaling and its key modulators, phosphodiesterases, are involved in diverse functions in the myocardium. Although the roles of PDE 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the heart are probably best understood, recent research indicates that PDE1 and PDE8 may also play important roles, as summarized in Fig. 1, 2. It is conceivable that other phosphodiesterase families may be found to regulate myocardial signaling as well. It appears that multiple PDE isoforms in the myocardium regulate various different functions by associating with distinct cyclic nucleotide signaling pathways. Future development of more selective PDE inhibitors and genetically engineered mice will allow more precise characterization of the function of individual PDEs in the heart, as well as enabling new sites to be targeted for pharmacological intervention in the heart and elsewhere. The beneficial effects seen with PDE1 and PDE5 inhibition indicate that potentiation of cGMP signaling may be a powerful tool to fight pathological cardiac remodeling and dysfunction. The increased myocyte apoptosis observed upon PDE3 inhibition indicates that clinical use of PDE3 in targeting other tissues will need to account for potential cardiovascular side effects. Conversely, preservation of PDE3 function in the failing heart may be important for prevention of myocyte apoptosis and improvement of cardiac function.

Fig. 1.

cAMP-mediated signaling pathways in the left ventricular cardiomyocyte. When an external stimulus, particularly a β-adrenergic agonist, binds to a β-AR, AC becomes activated, resulting in the production of cAMP. Cellular cAMP primarily serves to activate PKA. PKA phosphorylates a number of targets in the myocyte. Phosphorylation of targets involving Ca 2+ cycling increases myocyte contractility. Phosphorylation of transcription factors/regulators regulates gene expression, promoting myocyte hypertrophic growth and apoptosis. By degrading cAMP, a number of PDEs are involved in regulation of these processes, often in different subcellular compartments. PDE3, PDE4 and PDE8 are all implicated in regulating myocyte excitation-contraction coupling via modulation of LTCC, RyR2 and PLB/SERCA2, and so are particularly important in modulating the contractile response. By negatively regulating ICER in a PKA-dependent manner, PDE3 is also antiapoptotic. PDE2 appears to be most important in cGMP-mediated modulation of cAMP levels, while the role of PDE1 in regulating myocyte cAMP is less well characterized.

Fig. 2.

cGMP-mediated signaling pathways in the left ventricular cardiomyocyte. cGMP can be produced by activation of either sGC via NOS/NO, or pGC via natriuretic peptides (ANP/BNP/CNP). cGMP produced by the 2 pathways appears to be compartmentalized into different regions of the myocyte. cGMP activates PKG, which has a number of cellular effects. Via PKG-mediated phosphorylation of LTCCs, PKG reduces myocyte contractility. PKG also inhibits a number of pro-hypertrophic mediators (such as Cn, NFAT, MEK/ERK1/2) in the myocyte, primarily through activation of RGS2, which blunts both Gαs and Gαq signaling. Cardiac cGMP levels are regulated primarily by PDE1 and PDE5, and inhibition of either of these enzymes appears to attenuate cardiac hypertrophy, and in the case of PDE5, also contractility. Via activation of PDE2, cGMP also modulates contractile functions in a species dependent manner. Note that these diagrams are based on observations in left ventricular myocytes, and some signaling pathways will be altered when looking at myocytes from other regions of the heart. AC: adenylyl cyclase; ANP: atrial natriuretic peptide; AT1R: angiotensin II type 1 receptor; β-AR: beta adrenergic receptor; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; Cn: calcineurin; CNP: C-type natriuretic peptide; ERK1/2: extracellular signal-regulated kinase ½; Gαq: heterotrimeric G protein, Gαq class, alpha subunit; Gαs: heterotrimeric G protein, Gαs class, alpha subunit; ICER: inducible cAMP early repressor; LTCC: L-type Ca 2+ channel; MEK: mitogen activated ERK kinase; NFAT: nuclear factor of activated T-cells; NO: nitric oxide; NOS: NO synthase; pGC: particulate quanylyl cyclase; PKA: protein kinase A; PKG: protein kinase G; PLB: phospholamban; RGS2: RyR2: the cardiac ryanodine receptor; SERCA2: the cardiac SR Ca 2+ -release channel; sGC: soluble guanylyl cyclase; SR: sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH HL-077789 and HL088400 (to Dr. Yan) and American Heart Association EIA 0740021N (to Dr. Yan)

References

- 1.Ding B, Abe J, Wei H, Xu H, Che W, Aizawa T, Liu W, Molina CA, Sadoshima J, Blaxall BC, Berk BC, Yan C. A positive feedback loop of phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE3) and inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER) leads to cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14771–14776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506489102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang M, Kass DA. Phosphodiesterases and cardiac cGMP: evolving roles and controversies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman RD, Gros R. New insights into the regulation of cAMP synthesis beyond GPCR/G protein activation: Implications in cardiovascular regulation. Life Sci. 2007;81:267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Levin LR, Buck J. Role of Soluble Adenylyl Cyclase in the Heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circul Physiol. 2012;302:H-538–H-543. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00701.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iancu RV, Ramamurthy G, Harvey RD. Spatial and temporal aspects of cAMP signalling in cardiac myocytes. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:1343–1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.05020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halls ML, Cooper DMF. Sub-picomolar relaxin signalling by a pre-assembled RXFP1, AKAP79, AC2, β-arrestin 2, PDE4D3 complex. EMBO J. 2010;29:2772–2787. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaccolo M. cAMP signal transduction in the heart: understanding spatial control for the development of novel therapeutic strategies. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:50–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Métrich M, Berthouze M, Morel E, Crozatier B, Gomez AM, Lezoualc’h F. Role of the cAMP-binding protein Epac in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology. Pflügers Archiv Eur J Physiol. 2009;459:535–546. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0747-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai EJ, Kass DA. Cyclic GMP signaling in cardiovascular pathophysiology and therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:216–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro LRV, Verde I, Cooper DM, Fischmeister R. Cyclic guanosine monophosphate compartmentation in rat cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 2006;113:2221–2228. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.599241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bender AT, Beavo JA. Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterases: Molecular Regulation to Clinical Use. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:488–520. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conti M, Beavo J. Biochemistry and Physiology of Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterases: Essential Components in Cyclic Nucleotide Signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:481–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.150444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller CL, Yan C. Targeting cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase in the heart: therapeutic implications. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3:507–515. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9203-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonnenburg WK, Seger D, Beavo JA. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding the “61-kDa” calmodulin-stimulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Tissue-specific expression of structurally related isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:645–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan C, Zhao AZ, Bentley JK, Beavo JA. The Calmodulin-dependent Phosphodiesterase Gene PDE1C Encodes Several Functionally Different Splice Variants in a Tissue-specific Manner. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25699–25706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan C, Kim D, Aizawa T, Berk BC. Functional Interplay Between Angiotensin II and Nitric Oxide. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:26–36. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000046231.17365.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller CL, Oikawa M, Cai Y, Wojtovich AP, Nagel DJ, Xu X, Xu H, Florio V, Rybalkin SD, Beavo JA, Chen Y-F, Li J-D, Blaxall BC, Abe J, Yan C. Role of Ca2+/Calmodulin-Stimulated Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterase 1 in Mediating Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2009;105:956–964. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.198515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagel DJ, Aizawa T, Jeon K-I, Liu W, Mohan A, Wei H, Miano JM, Florio VA, Gao P, Korshunov VA, Berk BC, Yan C. Role of Nuclear Ca2+/Calmodulin-Stimulated Phosphodiesterase 1A in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Growth and Survival. Circ Res. 2006;98:777–784. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000215576.27615.fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller CL, Cai Y, Oikawa M, Thomas T, Dostmann WR, Zaccolo M, Fujiwara K, Yan C. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 1A: a key regulator of cardiac fibroblast activation and extracellular matrix remodeling in the heart. Basic Res Cardiol. 2011;106:1023–1039. doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0228-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bender AT, Beavo JA. PDE1B2 regulates cGMP and a subset of the phenotypic characteristics acquired upon macrophage differentiation from a monocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:460–465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509972102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed TM, Repaske DR, Snyder GL, Greengard P, Vorhees CV. Phosphodiesterase 1B Knock-Out Mice Exhibit Exaggerated Locomotor Hyper-activity and DARPP-32 Phosphorylation in Response to Dopamine Agonists and Display Impaired Spatial Learning. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5188–5197. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05188.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanda N, Watanabe S. Regulatory roles of adenylate cyclase and cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases 1 and 4 in interleukin-13 production by activated human T cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62:495–507. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rybalkin SD, Rybalkina I, Beavo JA, Bornfeldt KE. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 1C promotes human arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ Res. 2002;90:151–157. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.104108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han P, Werber J, Surana M, Fleischer N, Michaeli T. The calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphodiesterase PDE1C down-regulates glucose-induced insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22337–22344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunkern TR, Hatzelmann A. Characterization of inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 1C on a human cellular system. FEBS J. 2007;274:4812–4824. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallis RM, Corbin JD, Francis SH, Ellis P. Tissue distribution of phosphodiesterase families and the effects of sildenafil on tissue cyclic nucleotides, platelet function, and the contractile responses of trabeculae carneae and aortic rings in vitro. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vandeput F, Wolda SL, Krall J, Hambleton R, Uher L, McCaw KN, Radwanski PB, Florio V, Movsesian MA. Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterase PDE1C1 in Human Cardiac Myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32749–32757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loughney K, Martins TJ, Harris EAS, Sadhu K, Hicks JB, Sonnenburg WK, Beavo JA, Ferguson K. Isolation and Characterization of cDNAs Corresponding to Two Human Calcium, Calmodulin-regulated, 3′,5′-Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:796–806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beavo JA, Francis SH, Houslay MD. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases in health and disease. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mongillo M, McSorley T, Evellin S, Sood A, Lissandron V, Terrin A, Huston E, Hannawacker A, Lohse MJ, Pozzan T, Houslay MD, Zaccolo M. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer-Based Analysis of cAMP Dynamics in Live Neonatal Rat Cardiac Myocytes Reveals Distinct Functions of Compartmentalized Phosphodiesterases. Circ Res. 2004;95:67–75. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000134629.84732.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun B, Li H, Shakur Y, Hensley J, Hockman S, Kambayashi J, Manganiello VC, Liu Y. Role of phosphodiesterase type 3A and 3B in regulating platelet and cardiac function using subtype-selective knockout mice. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1765–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moberg E, Enoksson S, Hagström-Toft E. Importance of phosphodiesterase 3 for the lipolytic response in adipose tissue during insulin-induced hypoglycemia in normal man. Horm Metab Res. 1998;30:684–688. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi YH, Ekholm D, Krall J, Ahmad F, Degerman E, Manganiello VC, Movsesian MA. Identification of a novel isoform of the cyclic-nucleotide phosphodiesterase PDE3A expressed in vascular smooth-muscle myocytes. Biochem J. 2001;353:41–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shakur Y, Holst LS, Landstrom TR, Movsesian M, Degerman E, Manganiello V. Regulation and function of the cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase (PDE3) gene family. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;66:241–277. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)66031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kostic MM, Erdogan S, Rena G, Borchert G, Hoch B, Bartel S, Scotland G, Huston E, Houslay MD, Krause E-G. Altered Expression of PDE1 and PDE4 Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterase Isoforms in 7-oxo-prostacyclin-preconditioned Rat Heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:3135–3146. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mokni W, Keravis T, Etienne-Selloum N, Walter A, Kane MO, Schini-Kerth VB, Lugnier C. Concerted Regulation of cGMP and cAMP Phosphodiesterases in Early Cardiac Hypertrophy Induced by Angiotensin II. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richter W, Xie M, Scheitrum C, Krall J, Movsesian MA, Conti M. Conserved expression and functions of PDE4 in rodent and human heart. Basic Res Cardiol. 2011;106:249–262. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0138-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leroy J, Richter W, Mika D, Castro LRV, Abi-Gerges A, Xie M, Scheitrum C, Lefebvre F, Schittl J, Mateo P, Westenbroek R, Catterall WA, Charpentier F, Conti M, Fischmeister R, Vandecasteele G. Phosphodiesterase 4B in the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel complex regulates Ca2+ current and protects against ventricular arrhythmias in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2651–2661. doi: 10.1172/JCI44747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotera J, Fujishige K, Imai Y, Kawai E, Michibata H, Akatsuka H, Yanaka N, Omori K. Genomic origin and transcriptional regulation of two variants of cGMP binding cGMP specific phosphodiesterases. Eur J Biochem. 1999;262:866–873. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pokreisz P, Vandenwijngaert S, Bito V, Van den Bergh A, Lenaerts I, Busch C, Marsboom G, Gheysens O, Vermeersch P, Biesmans L, Liu X, Gillijns H, Pellens M, Van Lommel A, Buys E, Schoonjans L, Vanhaecke J, Verbeken E, Sipido K, Herijgers P, Bloch KD, Janssens SP. Ventricular Phosphodiesterase-5 Expression Is Increased in Patients With Advanced Heart Failure and Contributes to Adverse Ventricular Remodeling After Myocardial Infarction in Mice. Circulation. 2009;119:408–416. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.822072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corbin J, Rannels S, Neal D, Chang P, Grimes K, Beasley A, Francis S. Sildenafil citrate does not affect cardiac contractility in human or dog heart. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19:747–752. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagendran J, Archer SL, Soliman D, Gurtu V, Moudgil R, Haromy A, St Aubin C, Webster L, Rebeyka IM, Ross DB, Light PE, Dyck JRB, Michelakis ED. Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Is Highly Expressed in the Hypertrophied Human Right Ventricle, and Acute Inhibition of Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Improves Contractility. Circulation. 2007;116:238–248. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kass DA, Takimoto E, Nagayama T, Champion HC. Phosphodiesterase regulation of nitric oxide signaling. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang M, Koitabashi N, Nagayama T, Rambaran R, Feng N, Takimoto E, Koenke T, O’Rourke B, Champion HC, Crow MT, Kass DA. Expression, Activity, and Pro-Hypertrophic Effects of PDE5A in Cardiac Myocytes. Cell Signal. 2008;20:2231–2236. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lukowski R, Rybalkin SD, Loga F, Leiss V, Beavo JA, Hofmann F. Cardiac hypertrophy is not amplified by deletion of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I in cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5646–5651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001360107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patrucco E, Albergine MS, Santana LF, Beavo JA. Phosphodiesterase 8A (PDE8A) regulates excitation-contraction coupling in ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:330–333. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rentero C, Monfort A, Puigdomènech P. Identification and distribution of different mRNA variants produced by differential splicing in the human phosphodiesterase 9A gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:686–692. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galindo-Tovar A, Vargas ML, Kaumann AJ. Phosphodiesterases PDE3 and PDE4 jointly control the inotropic effects but not chronotropic effects of (−)-CGP12177 despite PDE4-evoked sinoatrial bradycardia in rat atrium. Naunyn-Schmied Arch Pharmacol. 2008;379:379–384. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaumann AJ. Phosphodiesterases reduce spontaneous sinoatrial beating but not the “fight or flight” tachycardia elicited by agonists through Gs-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DiFrancesco D, Tortora P. Direct activation of cardiac pacemaker channels by intracellular cyclic AMP. Nature. 1991;351:145–147. doi: 10.1038/351145a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alig J, Marger L, Mesirca P, Ehmke H, Mangoni ME, Isbrandt D. Control of heart rate by cAMP sensitivity of HCN channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12189–12194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810332106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galindo Tovar A, Kaumann AJ. Phosphodiesterase 4 blunts inotropism and arrhythmias but not sinoatrial tachycardia of (−)-adrenaline mediated through mouse cardiac β1adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:710–720. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galindo-Tovar A, Vargas ML, Kaumann AJ. Function of cardiac [beta]1-and [beta]2-adrenoceptors of newborn piglets: Role of phosphodiesterases PDE3 and PDE4. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;638:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Christ T, Galindo-Tovar A, Thoms M, Ravens U, Kaumann AJ. Inotropy and L-type Ca2+ current, activated by β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, are differently controlled by phosphodiesterases 3 and 4 in rat heart. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:62–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan C, Miller CL, Abe J. Regulation of Phosphodiesterase 3 and Inducible cAMP Early Repressor in the Heart. Circ Res. 2007;100:489–501. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258451.44949.d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matthew AM. PDE3 inhibition in dilated cardiomyopathy: reasons to reconsider. J Card Fail. 2003;9:475–480. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(03)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh A, Redden JM, Kapiloff MS, Dodge-Kafka KL. The Large Isoforms of A-Kinase Anchoring Protein 18 Mediate the Phosphorylation of Inhibitor-1 by Protein Kinase A and the Inhibition of Protein Phosphatase 1 Activity. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:533–540. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.065425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Layland J, Li J-M, Shah AM. Role of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase in the contractile response to exogenous nitric oxide in rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 2002;540:457–467. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.014126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang L, Liu G, Zakharov SI, Bellinger AM, Mongillo M, Marx SO. Protein kinase G phosphorylates Cav1. 2 alpha1c and beta2 subunits. Circ Res. 2007;101:465–474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dittrich M, Jurevicius J, Georget M, Rochais F, Fleischmann B, Hescheler J, Fischmeister R. Local response of L-type Ca(2+) current to nitric oxide in frog ventricular myocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 2001;534:109–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rivet-Bastide M, Vandecasteele G, Hatem S, Verde I, Bénardeau A, Mercadier JJ, Fischmeister R. cGMP-stimulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase regulates the basal calcium current in human atrial myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2710–2718. doi: 10.1172/JCI119460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Méry PF, Lohmann SM, Walter U, Fischmeister R. Ca2+ current is regulated by cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase in mammalian cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1197–1201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fischmeister R, Castro L, Abi-Gerges A, Rochais F, Vandecasteele G. Species- and tissue-dependent effects of NO and cyclic GMP on cardiac ion channels. Comp Biochem Physiol Part A: Mol Integ Physiol. 2005;142:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vandecasteele G, Verde I, Rücker-Martin C, Donzeau-Gouge P, Fischmeister R. Cyclic GMP regulation of the L-type Ca2+ channel current in human atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2001;533:329–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0329a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mongillo M, Tocchetti CG, Terrin A, Lissandron V, Cheung Y-F, Dostmann WR, Pozzan T, Kass DA, Paolocci N, Houslay MD, Zaccolo M. Compartmentalized phosphodiesterase-2 activity blunts beta-adrenergic cardiac inotropy via an NO/cGMP-dependent pathway. Circ Res. 2006;98:226–234. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000200178.34179.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kerfant B-G, Zhao D, Lorenzen-Schmidt I, Wilson LS, Cai S, Chen SRW, Maurice DH, Backx PH. PI3Kγ Is Required for PDE4, not PDE3, Activity in Subcellular Microdomains Containing the Sarcoplasmic Reticular Calcium ATPase in Cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2007;101:400–408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Packer M, Carver JR, Rodeheffer RJ, Ivanhoe RJ, DiBianco R, Zeldis SM, Hendrix GH, Bommer WJ, Elkayam U, Kukin ML. Effect of oral milrinone on mortality in severe chronic heart failure. The PROMISE Study Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1468–1475. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111213252103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patrucco E, Notte A, Barberis L, Selvetella G, Maffei A, Brancaccio M, Marengo S, Russo G, Azzolino O, Rybalkin SD, Silengo L, Altruda F, Wetzker R, Wymann MP, Lembo G, Hirsch E. PI3K[gamma] Modulates the Cardiac Response to Chronic Pressure Overload by Distinct Kinase-Dependent and -Independent Effects. Cell. 2004;118:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Arcangelis V, Liu R, Soto D, Xiang Y. Differential association of phosphodiesterase 4D isoforms with beta2-adrenoceptor in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33824–33832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baillie GS, Sood A, McPhee I, Gall I, Perry SJ, Lefkowitz RJ, Houslay MD. beta-Arrestin-mediated PDE4 cAMP phosphodiesterase recruitment regulates beta-adrenoceptor switching from Gs to Gi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:940–945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262787199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 71.Richter W, Day P, Agrawal R, Bruss MD, Granier S, Wang YL, Rasmussen SGF, Horner K, Wang P, Lei T, Patterson AJ, Kobilka B, Conti M. Signaling from beta1- and beta2-adrenergic receptors is defined by differential interactions with PDE4. EMBO J. 2008;27:384–393. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lehnart SE, Wehrens XHT, Reiken S, Warrier S, Belevych AE, Harvey RD, Richter W, Jin S-LC, Conti M, Marks AR. Phosphodiesterase 4D Deficiency in the Ryanodine-Receptor Complex Promotes Heart Failure and Arrhythmias. Cell. 2005;123:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beca S, Helli PB, Simpson JA, Zhao D, Farman GP, Jones P, Tian X, Wilson LS, Ahmad F, Chen SRW, Movsesian MA, Manganiello V, Maurice DH, Conti M, Backx PH. Phosphodiesterase 4D Regulates Baseline Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Release and Cardiac Contractility, Independently of L-Type Ca2+ Current. Circ Res. 2011;109:1024–1030. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.250464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takimoto E, Belardi D, Tocchetti CG, Vahebi S, Cormaci G, Ketner EA, Moens AL, Champion HC, Kass DA. Compartmentalization of Cardiac β-Adrenergic Inotropy Modulation by Phosphodiesterase Type 5. Circulation. 2007;115:2159–2167. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.643536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Borlaug BA, Melenovsky V, Marhin T, Fitzgerald P, Kass DA. Sildenafil Inhibits β-Adrenergic-Stimulated Cardiac Contractility in Humans. Circulation. 2005;112:2642–2649. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Takimoto E, Champion HC, Belardi D, Moslehi J, Mongillo M, Mergia E, Montrose DC, Isoda T, Aufiero K, Zaccolo M, Dostmann WR, Smith CJ, Kass DA. cGMP Catabolism by Phosphodiesterase 5A Regulates Cardiac Adrenergic Stimulation by NOS3-Dependent Mechanism. Circ Res. 2005;96:100–109. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000152262.22968.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ding B, Abe J, Wei H, Huang Q, Walsh RA, Molina CA, Zhao A, Sadoshima J, Blaxall BC, Berk BC, Yan C. Functional role of phosphodiesterase 3 in cardiomyocyte apoptosis: implication in heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:2469–2476. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165128.39715.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Francis SH, Blount MA, Corbin JD. Mammalian Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterases: Molecular Mechanisms and Physiological Functions. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:651–690. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yan C, Ding B, Shishido T, Woo C-H, Itoh S, Jeon K-I, Liu W, Xu H, McClain C, Molina CA, Blaxall BC, Abe J. Activation of Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 5 Reduces Cardiac Apoptosis and Dysfunction via Inhibition of a Phosphodiesterase 3A/Inducible cAMP Early Repressor Feedback Loop. Circ Res. 2007;100:510–519. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259045.49371.9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abi-Gerges A, Richter W, Lefebvre F, Mateo P, Varin A, Heymes C, Samuel J-L, Lugnier C, Conti M, Fischmeister R, Vandecasteele G. Decreased Expression and Activity of cAMP Phosphodiesterases in Cardiac Hypertrophy and Its Impact on β-Adrenergic cAMP Signals. Circ Res. 2009;105:784–792. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ma D, Fu L, Shen J, Zhou P, Gao Y, Xie R, Li Y, Han Y, Wang Y, Wang F. Interventional effect of valsartan on expression of inducible cAMP early repressor and phosphodiesterase 3A in rats after myocardial infarction. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;602:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Holbrook M, Coker SJ. Effects of zaprinast and rolipram on platelet aggregation and arrhythmias following myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion in anaesthetized rabbits. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1973–1979. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12. 6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell. 2000;101:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wehrens XHT, Lehnart SE, Huang F, Vest JA, Reiken SR, Mohler PJ, Sun J, Guatimosim S, Song L-S, Rosemblit N, D’Armiento JM, Napolitano C, Memmi M, Priori SG, Lederer WJ, Marks AR. FKBP12. 6 Deficiency and Defective Calcium Release Channel (Ryanodine Receptor) Function Linked to Exercise-Induced Sudden Cardiac Death. Cell. 2003;113:829–840. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. PKA Phosphorylation Dissociates FKBP12. 6 from the Calcium Release Channel (Ryanodine Receptor): Defective Regulation in Failing Hearts. Cell. 2000;101:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Molina CE, Leroy J, Richter W, Xie M, Scheitrum C, Lee I-O, Maack C, Rucker-Martin C, Donzeau-Gouge P, Verde I, Llach A, Hove-Madsen L, Conti M, Vandecasteele G, Fischmeister R. Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate Phosphodiesterase Type 4 Protects Against Atrial Arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:2182–2190. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vandeput F, Krall J, Ockaili R, Salloum FN, Florio V, Corbin JD, Francis SH, Kukreja RC, Movsesian MA. cGMP-Hydrolytic Activity and Its Inhibition by Sildenafil in Normal and Failing Human and Mouse Myocardium. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 2009;330:884–891. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.154468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kukreja RC, Ockaili R, Salloum F, Yin C, Hawkins J, Das A, Xi L. Cardio-protection with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition – a novel preconditioning strategy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fisher PW, Salloum F, Das A, Hyder H, Kukreja RC. Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibition With Sildenafil Attenuates Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis and Left Ventricular Dysfunction in a Chronic Model of Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity. Circulation. 2005;111:1601–1610. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160359.49478.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Takimoto E, Champion HC, Li M, Belardi D, Ren S, Rodriguez ER, Bedja D, Gabrielson KL, Wang Y, Kass DA. Chronic inhibition of cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase 5A prevents and reverses cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2005;11:214–222. doi: 10.1038/nm1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Das A, Xi L, Kukreja RC. Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibitor Sildenafil Preconditions Adult Cardiac Myocytes against Necrosis and Apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12944–12955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Koitabashi N, Aiba T, Hesketh GG, Rowell J, Zhang M, Takimoto E, Tomaselli GF, Kass DA. Cyclic GMP/PKG-dependent inhibition of TRPC6 channel activity and expression negatively regulates cardiomyocyte NFAT activation Novel mechanism of cardiac stress modulation by PDE5 inhibition. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Redondo J, Bishop JE, Wilkins MR. Effect of atrial natriuretic peptide and cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase inhibition on collagen synthesis by adult cardiac fibroblasts. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:1455–1462. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang M, Takimoto E, Hsu S, Lee DI, Nagayama T, Danner T, Koitabashi N, Barth AS, Bedja D, Gabrielson KL, Wang Y, Kass DA. Myocardial Remodeling Is Controlled by Myocyte-Targeted Gene Regulation of Phosphodiesterase Type 5. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:2021–2030. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Das A, Xi L, Kukreja RC. Protein Kinase G-dependent Cardioprotective Mechanism of Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibition Involves Phosphorylation of ERK and GSK3β. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29572–29585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801547200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Takimoto E, Koitabashi N, Hsu S, Ketner EA, Zhang M, Nagayama T, Bedja D, Gabrielson KL, Blanton R, Siderovski DP, Mendelsohn ME, Kass DA. Regulator of G protein signaling 2 mediates cardiac compensation to pressure overload and antihypertrophic effects of PDE5 inhibition in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:408–420. doi: 10.1172/JCI35620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chakir K, Zhu W, Tsang S, Woo AY-H, Yang D, Wang X, Zeng X, Rhee M-H, Mende U, Koitabashi N, Takimoto E, Blumer KJ, Lakatta EG, Kass DA, Xiao R-P. RGS2 is a primary terminator of [beta]2-adrenergic receptor-mediated Gi signaling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:1000–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Frantz S, Klaiber M, Baba HA, Oberwinkler H, Völker K, Gaβner B, Bayer B, Abeβer M, Schuh K, Feil R, Hofmann F, Kuhn M. Stress-Dependent Dilated Cardiomyopathy in Mice with Cardiomyocyte-Restricted Inactivation of Cyclic GMP-Dependent Protein Kinase I. Eur Heart J. 2011 Dec; doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr445. Epub ahead of print. Available from: http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/12/23/eurheartj.ehr445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Baim DS, McDowell AV, Cherniles J, Monrad ES, Parker JA, Edelson J, Braunwald E, Grossman W. Evaluation of a new bipyridine inotropic agent – milrinone – in patients with severe congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:748–756. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198309293091302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jaski BE, Fifer MA, Wright RF, Braunwald E, Colucci WS. Positive inotropic and vasodilator actions of milrinone in patients with severe congestive heart failure. Dose-response relationships and comparison to nitroprusside. J Clin Invest. 1985;75:643–649. doi: 10.1172/JCI111742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Amsallem E, Kasparian C, Haddour G, Boissel J-P, Nony P. Phosphodiesterase III inhibitors for heart failure. In: Nony P, editor. The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Chichester, UK: Wiley: 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Movsesian MA, Alharethi R. Inhibitors of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase PDE3 as adjunct therapy for dilated cardiomyopathy. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;11:1529–1536. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.11.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cuffe MS, Califf RM, Adams KF, Benza R, Bourge R, Colucci WS, Massie BM, O’Connor CM, Pina I, Quigg R, Silver MA, Gheorghiade M. Short-Term Intravenous Milrinone for Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Heart Failure A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2002;287:1541–1547. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.12.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Assad-Kottner C, Chen D, Jahanyar J, Cordova F, Summers N, Loebe M, Merla R, Youker K, Torre-Amione G. The Use of Continuous Milrinone Therapy as Bridge to Transplant Is Safe in Patients With Short Waiting Times. J Card Fail. 2008;14:839–843. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Canver CC, Chanda J. Milrinone for long-term pharmacologic support of the status 1 heart transplant candidates. Ann Thor Surg. 2000;69:1823–1826. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01313-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chapman TM, Goa KL. Cilostazol: a review of its use in intermittent claudication. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2003;3:117–138. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200303020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sun B, Le SN, Lin S, Fong M, Guertin M, Liu Y, Tandon NN, Yoshitake M, Kambayashi J-I. New mechanism of action for cilostazol: interplay between adenosine and cilostazol in inhibiting platelet activation. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2002;40:577–585. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200210000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang S, Cone J, Fong M, Yoshitake M, Kambayashi Ji, Liu Y. Interplay between inhibition of adenosine uptake and phosphodiesterase type 3 on cardiac function by cilostazol, an agent to treat intermittent claudication. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2001;38:775–783. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200111000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shakur Y, Fong M, Hensley J, Cone J, Movsesian MA, Kambayashi J-I, Yoshitake M, Liu Y. Comparison of the effects of cilostazol and milrinone on cAMP-PDE activity, intracellular cAMP and calcium in the heart. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2002;16:417–427. doi: 10.1023/a:1022186402442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kass DA, Champion HC, Beavo JA. Phosphodiesterase type 5: expanding roles in cardiovascular regulation. Circ Res. 2007;101:1084–1095. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bergot E, Magnier R, Zalcman G. Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors for Pulmonary Hypertension. N Eng J Med. 2010;362:559–560. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0912127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD. PDE5 Inhibition With Sildenafil Improves Left Ventricular Diastolic Function, Cardiac Geometry, and Clinical Status in Patients With Stable Systolic Heart Failure/Clinical Perspective. Circulation: Heart Fail. 2011;4:8–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.944694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Giannetta E, Isidori AM, Galea N, Carbone I, Mandosi E, Vizza CD, Naro F, Morano S, Fedele F, Lenzi A. Chronic Inhibition of Cyclic GMP Phosphodiesterase 5A Improves Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Myocardial Tagging. Circulation. 2012;125:2323–2333. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.063412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Herrmann HC, Chang G, Klugherz BD, Mahoney PD. Hemodynamic effects of sildenafil in men with severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1622–1626. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006013422201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Denardo SJ, Wen X, Handberg EM, Bairey Merz CN, Sopko GS, Cooper-Dehoff RM, Pepine CJ. Effect of Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibition on Microvascular Coronary Dysfunction in Women: A Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Ancillary Study. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:483–487. doi: 10.1002/clc.20935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]