Abstract

Previous research indicates that Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is well conceptualized as a dimensional construct that can be represented using normal personality traits. A previous study successfully developed and validated a BPD measure embedded within a normal trait measure, the Minnesota Borderline Personality Disorder Scale (MBPD). The current study performed a further validation of the MBPD by examining its convergent validity, external correlates, and heritability in a sample of 429 female twins. The MBPD correlated strongly with the SCID-II screener for BPD and moderately with external correlates. Moreover, the MBPD and SCID-II screener exhibited very similar patterns of external correlations. Additionally, results indicated that the genetic and environmental influences on MBPD overlap with the genetic and environmental influences on the SCID-II screener, which suggests that these scales are measuring the same construct. This data provide further evidence for the construct validity of the MBPD.

Keywords: Borderline Personality Disorder, Normal Personality, Nomological Network, Behavioral Genetics

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is characterized by impulsivity, affective instability, inappropriate anger, self-injury, abandonment fears, unstable relationships, and identity disturbance (APA, 2000 BPD is highly comorbid with both Axis I and Axis II psychopathology including depression (Fonagy & Bateman, 2006;), anxiety disorders (Zanarini, Frankenburg, Dubo, et al., 1998), eating disorders (Striegel-Moore, Garvin, Dohm, & Rosenheck, 1999), and substance use disorders (Paris, 1997). Traditionally, BPD was thought of as categorical (yes/no) construct. However, this view has been shifting based on evidence that borderline features fall along a continuum (Edens, Marcus, & Ruiz, 2008; Trull, Widiger, Lynam, & Costa, 2003). For instance, taxometric research suggests that BPD is dimensional (Edens et al., 2008), and continuous measures are consistently and substantially more reliable and valid for psychopathology in general (Markon, Chmielewski, & Miller, 2011) and personality pathology in particular (Morey, Hopwood, Gunderson, et al., 2007). Therefore, there is a clear need to construct and identify measures that assess BPD in a dimensional manner.

Fortunately, there is a long tradition of dimensional assessment of traits from basic personality theory (e.g., Pervin& John, 2008) from which psychopathologists can draw. Indeed, robust associations have been identified between BPD features and normal traits, such as those of the Five-Factor Model (FFM) (Costa, 1992). For instance, Trull, Widiger, and Burr (2001) found that the trait of neuroticism from FFM of normal personality accounts for a significant amount of variance in BPD features in both a clinical sample and undergraduate sample, even after controlling for all other personality disorders. Likewise, Morey and Zanarini (2000) found that the neuroticism factor could distinguish BPD and non-BPD individuals and that the entire FFM model accounted for a significant proportion of variance in BPD diagnosis for both self-report and interview measures. These studies provide considerable evidence that BPD features can be identified using indicators of normal personality traits. Accordingly, researchers have developed a number of methods for assessing BPD using existing personality trait systems (Costa & Widiger, 2002; Mullins-Sweatt et al., 2012). However until recently, there was no BPD indicator from the extensively validated Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Patrick, Curtin, & Tellegen, 2002; Tellegen, 1982). Bornovalova, Hicks, Patrick, Iacono, and McGue (2011) developed the Minnesota Borderline Personality Disorder Scale (MBPD) using items from the MPQ pool with cross-validated correlations to other indicators of BPD. In the original validation study, the MBPD was highly and significantly correlated with both diagnostic and self-report measures of BPD, as well as established external correlates such as substance use and depression. The measure also discriminated BPD from antisocial features and provided incremental validity over negative emotionality for predicting BPD diagnostic symptoms, BPD diagnosis, and externalizing behaviors.

The MBPD has considerable potential for research on BPD. For instance, the MBPD can be used to provide an assessment of BPD features in samples where the MPQ was administered but other BPD measures were not, and allowing for additional research on the MBPD provides insights into the ability of trait instruments to assess PD constructs. However, further validation work in new samples and with novel validation criteria is needed to support the utility of the measure. The purpose of this study was to further evaluate the validity and generalizability of the MBPD in a sample of twin women during their transition from adolescence to adulthood. This sampling approach is valuable in light of the fact that peaks in BPD features occur normatively during transition to adulthood (Mattanah, Becker, Levy, Edell, & McGlashan, 1995). And, twin sampling allowed us to conduct exploratory analyses testing whether the MBPD shares etiological influences with other indicators of BPD in the current sample. Previous research has shown that the heritability of BPD in late adolescence is ~.48–.50 (Bornovalova, et al., 2013). Other studies have shown similar results regarding heritability for BPD features in late adolescence into early adulthood (Distel et al., 2011; Distel et al., 2008).

Present Study

In the current study we aimed to conduct a further validation of the MBPD in a large, community sample of young female twins. We had three general hypotheses. First, we expected that the MBPD would be strongly related to another validated measure of BPD. Second, we predicted that the MBPD would correlate with theoretically related constructs, although to a lesser degree than with other BPD measure. We selected external variables based on known correlates of BPD, including: negative affect (Trull, et al., 2000), impulsive behavior (Paris, 1997;), interpersonal problems (Fonagy & Bateman, 2006;), antisocial behaviors (Paris, 1997), eating disorders (Striegel-Moore, et al., 1999), major depressive disorder (Fonagy & Bateman, 2006;), and alcohol and drug use (Paris, 1997). Third, exploratory biometric models were expected to show that the MBPD shares etiological influences with other measures of BPD in the current sample. This allowed us to test if the same genetic and environmental influences give rise to responses on BPD measures despite a lack of item overlap.

Method

Participants

This study sample was drawn from a larger on-going project, the Twin Study of Hormones and Behavior across the Menstrual Cycle from the Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR; N ~ 18,000 twins; see Klump & Burt, 2006 for the description of the study and recruitment procedures). The current sample included 493 young women (238 twin pairs and 17 unpaired twins). Of the twin pairs, 141 were monozygotic pairs (MZ) and 114 were dizygotic (DZ). Participants ranged in age from 16 to 25 (M = 18.11, SD =1.93). MSUTR participants are demographically representative of the surrounding region (Burt & Klump, 2012). In the current sample, the ethnicity breakdown was: 77% Caucasian, 16% African American, 5% mixed, 1% Asian, 1% American Indian/Alaskan Native, an ethnic distribution representative of the general Michigan area (Burt & Klump, 2012).

Measures

Measures are organized into three categories: (a) the Minnesota Borderline Personality Disorder Scale, (b) convergent validity measure, and (c) external correlates. Diagnostic reliability was calculated from the kappa coefficient and internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha.

Minnesota Borderline Personality Disorder Scale, (MBPD; Bornovalova, Hicks, Patrick et al., 2011)

The MBPD is a 19-item scale developed using items from the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ, Patrick, et al., 2002) a well-validated omnibus measure of normal personality. Candidate items were identified in two samples—inner-city drug users (N = 146) and undergraduates (N =288) —by examining correlations between all MPQ items and diagnostic and self-report measures of BPD. Candidate items that were significantly correlated with BPD measures in both samples were retained for further analyses in a third sample of young adults from the community. Validation analyses were conducted with a special emphasis placed on potential BPD items providing incremental prediction over general negative affect as measured by MPQ Negative Emotionality. The final 19 items were drawn from the MPQ Stress Reaction, Alienation, Control, Aggression, Well-Being, and Absorption scales. MBPD scores were correlated strongly with scores on another personality inventory aimed at assessing BPD, the Personality Assessment Inventory Borderline Features scale (PAI-BOR; Morey, 1991) in the undergraduate sample (r = .80), and with an interview-based diagnosis of BPD in the drug user sample (r = .62). In the current sample, α = .76, and mean inter-item correlation was .15

Convergent validity measure

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality questionnaire (SCID-II screener; First & Gibbon, 1997b)

The SCID-II personality questionnaire screener (SCID-II screener) is a self-reported screening tool for personality disorders. The SCID-II screener in this study included 15 (yes/no) items to assess for the 9 DSM-IV BPD criteria. Wording of items corresponded with the SCID-II diagnostic interview for BPD. Additional items were used as probes for each criterion, (e.g. 3 items assessed identity disturbance, 2 items assessed for self-harm, 2 items assessed for impulsivity, 3 items assessed for inappropriate anger). Symptom counts were calculated by summing the fifteen BPD items. In the current sample α=.76 and mean inter-item correlation was .18.

External validity measures

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988)

PANAS scores were collected from participants for 45 consecutive days. Participants were asked to rate to the extent to which they experienced daily positive (e.g. excited) and negative (e.g. scared) on a five-point scale (1= very slightly and 5 = very much) for 20 items. The PANAS-PA was used as a measure of discriminant validity, as positive affect has been found to show a modest negative association with BPD symptoms (e.g., Samuel & Widiger, 2008). The PANAS-NA was used as an external correlate as negative affect is associated with BPD symptoms. Internal consistency was calculated from the item scores at baseline; for PANAS-NA, α = .83 and for PANAS-PA α = .88.

UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (UPPS-P; Lynam, Smith, Whiteside, & Cyders, 2006)

The UPPS-P is a 59-item inventory that measures five dimensions of impulsive behavior. The five subscales include Negative Urgency (tendency to engage in rash action in response to negative affect ), (lack of) Premeditation (i.e., tendency not to plan or think through consequences of behavior before acting, (lack of) Perseverance (i.e., inability to sustain attention or motivation on a task), Sensation-Seeking (i.e., preference for excitement, stimulation, and danger), and Positive Urgency (i.e., tendency to act rashly in response to strong positive affect). The subscales have 11, 13, 12, 10, and 14 items respectively, each of which are calculated by taking the mean of the items. The items have a 4-point Likert scale (1-strongly agree to 4-strongly disagree). Questions assess global lifetime traits. In the current sample Negative Urgency: α = .85; (lack of) Premeditation: α = .86; (lack of) Perseverance: α = .83; Sensation-Seeking: α =.83; Positive Urgency: α = .91.

Inventory of Interpersonal Problems Circumplex Scales (IIP-C; Alden, Wiggins, & Pincus, 1990)

The IIP-C is a 64-item self-report lifetime assessment of interpersonal difficulties. The inventory assesses interpersonal problems and includes eight 8-item subscales: Domineering, Vindictive, Cold, Socially Avoidant, Nonassertive, Exploitable, Overly Nurturant, and Intrusive, although items from this scale can also be summed to provide an overall index of interpersonal distress. As our interest in the current study involved the degree to which the MBPD relates to interpersonal problems in general, we focused on the total score. In the current sample, total score α = .94.

Subtypes of Antisocial Behavior Questionnaire (STAB; Burt & Donnellan, 2009)

The STAB is a self-report measure containing 32 items assessing three factors: Physical Aggression (AGG), Rule-Breaking (RB), and Social Aggression (SA). Items were rated on a five-point scale to assess frequencies of antisocial behaviors (1 being never and 5 being nearly all the time) across the lifetime. Previous work has demonstrated the ability of the STAB to distinguish college students, community adults, and adjudicated adults (Burt & Donnellan, 2009). In the current sample, αs were .86 for AGG, .85 for RB, and .85 for SA.

Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey (MEBS; Klump, McGue, & Iacono, 2000; Miller & Pumariega, 2001; von Ranson, Klump, Iacono, & McGue, 2005)

The MEBS1 is a 30 item lifetime self-report measure which assesses disordered eating attitudes and behaviors, including body dissatisfaction, weight preoccupation, binge eating, and compensatory behavior. The current study examined the total score of the MEBS (α = .88), which indexes higher levels of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID I; First & & Gibbon, 1997a)

The SCID-I was used to assess Major Depression Disorder (MDD), Alcohol Dependence (AD), and Substance Dependence (SD), Lifetime symptom counts were calculated for each disorder. Natural log transformations were used to reduce the skew and kurtosis of the symptom counts into an acceptable range respectively (Chou & Bentler, 1995). For example, MDD, AD, SD exhibited both unacceptable skew (4.68, 6.65, 13.02, respectively) and kurtosis (13.54, 49.20, 194.92, respectively) and log transformation improved skew ( 2.95, 5.01, 5.01 respectively) and kurtosis ( 8.35, 26.05, 26.05). The assessment of (SD) covered amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, opioids, and other drugs. The drug class for which a participant reported the most symptoms for was used as their number of SD symptoms. Inter-rater reliability for diagnostic decisions was: κ for Mood Disorders = 1.00; κ for Alcohol and Substance Disorders = 1.0.

Results

Convergent Validity and External Correlates

To establish the convergent validity of the MBPD, we examined its relationship with an established BPD measure, the SCID-II screener for BPD via Pearson correlations.2 Next, we tested the extent to which the MBPD was correlated with other theoretically related external variables. The same correlations were evaluated between the SCID-II screener and the external variables. Finally, we tested if there were significant differences in the magnitude of the relationship of MBPD with external correlates and SCID-II screener with external correlates using a transformation (Williams's T2 statistic) that accounts for the high correlation (.73) between MBPD and SCID-II screener (Steiger 1980).

Descriptive statistics for all measures are provided in Table 1. With regard to convergent validity, the MBPD demonstrated a strong, positive correlation with the SCID-II screener (r = .73, p < .001). The MBPD scores also evidenced moderate correlations with the PANAS-NA, UPPS subscales of Positive Urgency, Perseverance, and Premeditation, positive, STAB subscales of RB, and SA, the MEBS, and MDD (rs ranged from .21 – .47). The MBPD evidenced strong correlations with STAB aggression, and UPPS Negative Urgency (rs between .60 – .61), and small correlations with Alcohol and Substance Dependence (rs = .15). In support of its discriminant validity, the MBPD was uncorrelated with UPPS subscale of sensation-seeking, a negative correlation with PANAS-PA, and considerably lower correlations with STAB subscales of aggression and rule-breaking (indicators of adult antisocial behavior) (See Table 1). Moreover, only two external correlations significantly differed between the MBPD and SCID-II: the IIP-C and STAB rule-breaking scales were more strongly related to the SCID-II than MBPD. This suggests that both the SCID-II and the MBPD had very similar nomological networks.

Table 1.

MBPD/SCID-II screener with External Correlates

| Mean (SD) | MBPD | SCID-II | Correlations significantly different (Z value)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBPD | 24.29 (3.57) | _____ | .73*** | _____ | |

| SCID-II | 2.70 (2.77) | _____ | _____ | ||

| Negative Affect | PANAS-NA | 15.03 (3.72) | .37*** | .32*** | −1.62 |

| At baseline | 15.05 (4.98) | .24*** | .23*** | −.31 | |

| PANAS-PA | 22.98 (6.10) | −.19*** | −.18*** | .31 | |

| At baseline | 24.67 (7.17) | −.22*** | −.19*** | .93 | |

| UPPS Premeditation | 1.92 (.52) | .29*** | .24*** | −1.57 | |

| Impulsivity | UPPS Perseverance | 1.83 (.48) | .38*** | .34*** | .72 |

| UPPS Sensation-Seeking | 2.70 (.58) | .05 | −.02 | −1.31 | |

| UPPS Negative Urgency | 2.05 (.56) | .61*** | .60*** | −.39 | |

| UPPS Positive Urgency | 1.69 (.54) | 47*** | .46*** | −.35 | |

| Interpersonal Problems | IIP-C | .79 (.43) | .26*** | .38*** | 3.90*** |

| Antisocial Behavior | STAB Aggression | 18.03 ( 5.62) | .60*** | .55*** | −1.91 |

| STAB Rule Breaking | 12.21 (2.95) | .40*** | .48*** | 2.75** | |

| STAB Social Aggression | 21.45 (5.23) | .40*** | .36*** | −1.32 | |

| Eating Disorders | MEBS | 5.32 (5.13) | .37*** | .40*** | .99 |

| Major Depression a | .37 (1.27) | .31*** | .34*** | .96 | |

| Alcohol Dependence a | .14 (.73) | .15** | .15** | 0 | |

| Substance Dependence a | .15 (1.28) | .15** | .15** | 0 | |

Means from raw scores of symptoms counts are presented; all analyses used log-transformed, z-scored symptom counts.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Abbreviations: MBPD, Minnesota Borderline Personality Disorder Scale. SCID-II, Structured Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders Screener. STAB, Subtypes of Antisocial Behavior Survey. MEBS, Minnesota Eating Behaviors Survey.

Biometric Modeling

First, using a double-entry method, we estimated intraclass and cross-twin, cross-trait correlations to provide initial estimates of genetic and environmental influences on each phenotype and their association. Genetic influences are inferred if the monozygotic (MZ) correlation is greater than the dizygotic (DZ) correlation for a given measure. Shared environmental influences are inferred if the DZ correlation is greater than .5 the MZ correlation. Nonshared environmental influences are inferred when the MZ correlation is less than 1.0. As seen in Table 2, the pattern of twin correlations suggest genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental influences on both MBPD and the SCID-II screener. The cross-twin-cross-trait correlations also suggested an overlap between the two measures that is due to common genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental influences as indicated by a) the larger cross-twin, cross-trait correlations for MZ relative to DZ pairs, and b) the difference between the two sets of correlations was non-significant.

Table 2.

Intraclass and Cross-Twin, Cross-Trait Correlations for MBPD and SCID-II screener.

| Twin Correlations | MZ (N = 141 pairs) |

DZ (N = 114 pairs) |

Z Test of Equality | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraclass Correlations | ||||

| MBPD | .42 (.31,.51)*** | .27 (.14,.39)** | 1.87 | .062 |

| SCID-II | .35 (.24,.46)*** | .27 (.14, .39)** | .97 | .332 |

| Cross-Twin, Cross-Trait Correlations | ||||

| Tw A MBPD, Tw B SCID-II | .35 (.24,.46)*** | .24 (.11,.37)*** | 1.32 | .187 |

Interclass correlations are the within-trait, cross-twin correlations used to estimate heritability (e.g., MZ > DZ). Cross-twin, cross-trait correlations are used to estimate the overlap between genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental influences on the two measures The Z test of equality tests whether the correlation is significantly different between the MZ and DZ pairs.

Abbreviations: MBPD, Minnesota Borderline Personality Disorder Scale. SCID-II, Structured Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders Screener.

The twin correlation is significantly greater than 0 at p < .01.

The twin correlation is significantly greater than 0 at p < .001.

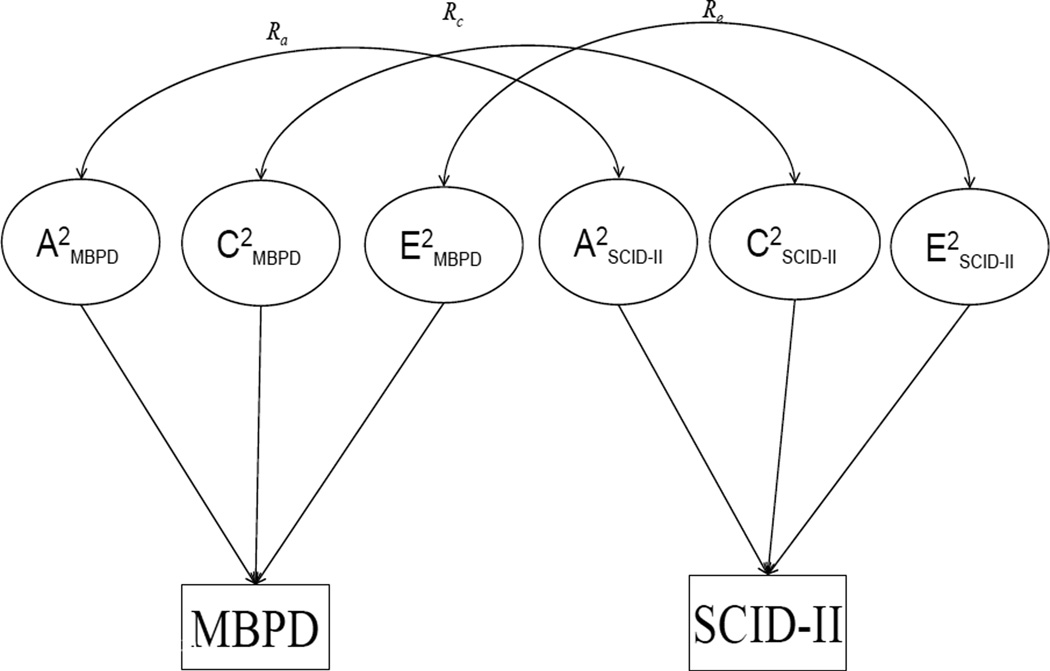

Next, in order to test whether common risk factors give rise to scores on the MBPD and SCID-II (indicating common influences on the phenotypes), we examined the common genetic and environmental influences contributing to the MBPD and SCID-II screener using bivariate Cholesky models using MX (Neale, Boker, Xie, & Maes, 1999). These models decompose the covariance between pairs of variables instead of just considering the influences on each variable alone (see Figure 1 for visual representation). More specifically, bivariate models allow the genetic, shared, and nonshared environmental influences on the MBPD to correlate with the same influences on SCID-II screener. The magnitude of the genetic, shared, and nonshared environmental correlations between the MBPD with the SCID-II screener signifies the extent to which such influences are common to both measures (Neal & Cardon, 1992).

Figure 1.

General Bivariate Model

General bivariate model showing genetic (rA) and environmental (rE) correlations between the MBPD and the SCID-II screener. Abbreviations: MBPD, Minnesota Borderline Personality Disorder Scale. SCID-II, Structured Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders Screener. A = additive genetic effects; E= nonshared environmental effects.

First, we fit the “full” model that allowed for genetic, shared and non-shared influences on MBPD to correlate with the influences on SCID-II screener. As indicated in Table 3, the univariate estimates in each model support the results obtained from the cross-twin, cross-trait matrix. In particular, the estimates indicate the presence of all three biometric components (A, C, and E), although the confidence intervals are quite broad and include zero in the full model for A and C. Thus, we fit a series of nested models that progressively dropped the genetic (rA), shared (rC), nonshared (rE) correlations. Model fit was evaluated using the change in −2 log likelihood value (Δ-2LL, which follows a chi-square distribution) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The BIC is a function of a model’s χ2 value and df, and penalizes the model fit for the retention of unnecessary parameters. Lower values (with a difference in BIC > 2) are indicative of better fit (Raftery, 1995). As seen in Table 3, dropping rC did not result in a significant different in the −2LL(Δ−2LL = .85, p = ns) but a significant improvement in model fit as indexed by the BIC (ΔBIC = −2.35); this model was retained as the best-fitting model. However, this model fit only slightly better than the model which dropped rA, most likely due to the relatively small sample size and power problems with classical twin models that include both A and C parameters (Eaves, Last, Young, et al., 1978).

Table 3.

Bivariate Cholesky Model Fit Statistics and Estimates for Full and Nested Models for MBPD and SCID-II screener.

| SCID-II Screener | MBPD | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -2LL | df | BIC | ΔBIC | ΔΧ2 | p | A | C | E | A | C | E | rA | rC | rE | |

| Base Model (rA, rC, rE) | 4514.98 | 941 | −349.67 | .15 (.00,.47) | .20 (.00,.41) | .65 (.52,.78) | .31 (.00,.54) | .12 (.00,.43) | .57 (.45,.72) | 1.0 (−1.0,1.0) | .94 (−1.0,1.0) | .61 (.51,.70) | |||

| Drop rA | 4516.80 | 942 | −351.54 | −1.86 | 1.82 | .18 | .00 (.00.12) | .32 (.18,.43) | .68 (.57,.80) | .07 (.00,.15) | .31 (.19,.46) | .63 (.52,.76) | 0.00 | 1.0 (.82,1.0) | .64 (.56,.72) |

| Drop rC | 4515.83 | 942 | −352.02 | −2.35 | 0.85 | .36 | .32 (.19,.49) | .05 (.00,.11) | .63 (.51,.77) | .44 (.25,.55) | .00 (.00,.11) | .56 (.45,.70) | 1.0 (.82,1.0) | --- | .60 (.50,.68) |

| Drop rE | 4625.27 | 942 | −297.30 | 52.38 | 110.29 | .00 | .57 (.42,.64) | .00 (.00,.14) | .43 (.36,.52) | .60 (.45,.67) | .00 (.00,.14) | .41 (.33..49) | 1.0 (.98,1.0) | .93 (−1.0,1.0) | 0 |

Notes. For both measures, best-fitting model is in bold.

Abbreviations: MBPD, Minnesota Borderline Personality Disorder Scale. SCID-II, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders Screener. −2LL, −2 log likelihood value. BIC, Bayesian information criteria. rA, gene correlations. rC,shared environment correlations. rE, nonshared environment correlations.

Parameter estimates from the best fitting model indicated that there was a large and significant rA of 1.00 (95% CI = .82, 1.00) between the MBPD and SCID-II screener, suggesting complete overlap in genetic factors for the two phenotypes. The nonshared environmental correlation was .60 (95% CI = .50, .69). This indicates that about 36% of the environmental factors for the MBPD overlaps with the environmental factors for the SCID-II screener, while the remaining 64% is unique to the MBPD (and vice versa). Interestingly, the univariate estimates changed for the bivariate model that constrained the rC parameter (see Table 3). For example, in the best fitting model that dropped rC, the shared environmental estimates decreased for both measures. Likewise, in the model that dropped rA, the genetic univariate estimates on each measure decreased. These changes are an indication of the overlap between measures, as the overall magnitude of rA and rC influences on each measure decreases when the shared genetic and shared environmental effects are constrained to be zero.

Discussion

In the current study we aimed to provide further validation of the MBPD in a sample of 493 young women by evaluating evidence for convergent and external validity as well as evidence that the MBPD is measuring the same etiological influences underlying BPD as a diagnostic BPD measure. Results indicated that the MBPD indeed exhibited strong, positive correlations with a DSM-based self-report measure of BPD, the SCID-II screener. Additionally, in line with our hypotheses, the MBPD was positively and moderately correlated with external correlates of BPD such as negative affect, impulsive and antisocial behaviors, interpersonal problems, and Axis I psychopathology. These findings are consistent with previous research on the nomological network of BPD (Goldman, Dangelo, & Demaso, 1993; Trull, et al., 2001; Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen, & Silk, 2003). Importantly, it should be noted that the SCID-II screener demonstrated similar correlations as the MBPD with all of the external correlates, suggesting that these measures are capturing the same latent construct of BPD.

Secondly, exploratory biometric models indicated that similar etiological influences of MBPD as with previous studies with this and other (Distel, et al., 2011; Distel, et al., 2008) studies. In particular, our study indicates that the MBPD was primarily influenced by genetic and nonshared environmental influences in young women. These effects are similar to that of previous studies (Bornovalova et al., 2009, 2013; Distel et al, 2008, 2011), with the latter two reports utilizing a different, non-overlapping measure (PAI-BOR). Next, bivariate models indicated that the genes and unique environmental factors that influence the MBPD also influence and SCID-II screener. Due to the relatively small sample size, we cannot rule out that only genetic and nonshared environmental influences influence both measures. However, the similarity of our results to previous studies from non-overlapping samples (Bornovalova et al., 2009 ; Distel et al., 2008, 2011) suggest common etiological influences on the two measures, in turn providing evidence that the two indicators are measuring a similar latent construct.

This is one of the few studies to focus on of the construct validity of trait measures of BPD features in young women sampled from the community (e.g. Bornovalova, et al., 2009; Sharp et al., 2011;). Hence, our study contributes to this literature by establishing a reliable and valid dimensional measure of BPD for use in similar samples as evidenced by the similarity of the MBPD in terms etiology and correlates with a non-overlapping measure, the SCID-II screener.. Moreover, the current study contributes further to the understanding of BPD in this particular age group, both in terms of etiology and external correlates. The potential of the MBPD for assessing BPD in this sample was particularly supported by its similarity, in terms of etiology and correlates, with a non-overlapping measure, the SCID-II screener.

There are four limitations that should be noted. First, the MBPD should be further validated in multiple, ethnically, diverse samples, including those of both female and male twins across different developmental periods, to examine gender differences in convergent validity, external correlates, and heritability. Second, the sample size was relatively small (particularly for a behavioral genetic study). Indeed, with a larger sample size, we would expect to see all three (genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental) parameters to correlate significantly across MBPD and the SCID-II screener. Third, in the current study, the MBPD was only compared to the SCID-II screener. Future studies would benefit from the use of a multi-assessment, multi-informant design, as previous work suggests that different assessment methods and informants provide unique information about BPD (Hopwood et al., 2008; Oltmanns & Turkheimer, 2009). Finally, despite item content that covers the major diagnostic domains of BPD, in the current study the MBPD was treated as a unidimensional construct. However, previous work with the DSM-IV based interviews of BPD consistently reveals a unidimensional factor structure (Clifton & Pilkonis, 2006; Johansen et al., 2004), or alternatively, a three-factor structure with factor correlations greater than .85 (Sanislow, et al, 2002). As such, this indicates that the use of MBPD as a unidimensional construct is appropriate.

Despite these limitations, the current study provided further evidence for the validity of the MBPD, and in turn further confidence for the estimation of BPD traits from the MPQ in large, longitudinal and epidemiological samples such as the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health Development Study, (Caspi, Begg, Dickson, et al., 1997), the Minnesota Twin and Family Study (Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, & McGue, 1999) that contain the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. As these studies include developmental, genetic and physiological perspectives, the availability of the MBPD opens up important new avenues for research on BPD using existing data. Finally, the MBPD may be useful to clinicians who give the MPQ to screen for personality issues.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health , NIMH (1 R01 MH0820-54) to Drs. Klump, Boker, Burt, Keel, Neale, and Dr. Cheryl Sisk. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

No conflict of interest exists for any of the authors.

The Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey (MEBS; previously known as the Minnesota Eating Disorder Inventory (M-EDI)) was adapted and reproduced by special permission of Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., 16204 North Florida Avenue, Lutz, Florida 33549, from the Eating Disorder Inventory (collectively, EDI and EDI-2) by Garner, Olmstead, & Polivy (1983) Copyright 1983 by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. Further reproduction of the MEBS is prohibited without prior permission from Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Twins are correlated at higher than chance rates, which could possibly inflate the strength of the correlation between our predictor and correlates. We selected two random subsets of twin from the sample (randomly selected one twin from each twin pair) and checked if the correlations differed significantly between the subsets/random halves. In over 95% of the cases there were no significant differences between random halves.

References

- Alden LE, Wiggins JS, Pincus AL. Construction of circumplex scales for the inventory of interpersonal problems. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990;55:521–536. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Text Revised. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Benning SD, Patrick CJ, Hicks BM, Blonigen DM, Krueger RF. Factor structure of the psychopathic personality inventory: Validity and implications for clinical assessment. Psychological Assessment. 2003;15:340–350. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Stability, change, and heritability of borderline personality disorder traits from adolescence to adulthood: A longitudinal twin study. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1335–1353. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Familial Transmission and Heritability of Childhood Disruptive Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:1066–1074. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Longitudinal Twin Study of Borderline Personality Disorder Traits and Substance Use in Adolescence: Developmental Change, Reciprocal Effects, and Genetic and Environmental Influences. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2013;4:23–32. doi: 10.1037/a0027178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG, McGue M. Development and Validation of the Minnesota Borderline Personality Disorder Scale. Assessment. 2011;18:234–252. doi: 10.1177/1073191111398320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, Donnellan MB. Development and Validation of the Subtypes of Antisocial Behavior Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior. 2009;35:376–398. doi: 10.1002/ab.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, Klump KL. Etiological Distinctions between Aggressive and Nonaggressive Antisocial Behavior: Results from a Nuclear Twin Family Model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:1059–1071. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9632-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Begg D, Dickson N, Langley J, et al. Identification of personality types at risk for poor health and injury in late adolescence. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 1995;5:330–350. [Google Scholar]

- Chou C, Bentler PM. Estimates and tests in structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton A, Pilkonis PA. Evidence for a single latent class of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders borderline personality pathology. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2006;48:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, Widiger TA. Personality Disorders and the Five Factor Model of Personality. 2nd ed. Washington DC: APA; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Distel MA, Carlier A, Middeldorp CM, Derom CA, Lubke GH, Boomsma DI. Borderline Personality Traits and Adult Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms: A Genetic Analysis of Comorbidity. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B-Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2011;156B:817–825. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distel MA, Rebollo-Mesa I, Willemsen G, Derom CA, Trull TJ, Boomsma DI. Familial Transmission of Borderline Personality Disorder Features. Behavior Genetics. 2008;38:638–638. [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Last KA, Young PA, Martin NG. Model-fitting approaches to the analysis of human behavior. Heredity. 1978;41:249–320. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1978.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens JF, Marcus DK, Ruiz MA. Taxometric analyses of borderline personality features in a large-scale male and female offender sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:705–711. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M. User's guide for the Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders SCID-I: clinician version. American Psychiatric Publishers Incorporated. 1997a [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M. User's guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders: SCID-II. American Psychiatric Publications Incorporated; 1997b. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Bateman AW. Mechanisms of change in mentalization-based treatment of BPD. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:411–430. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A, Maffei C, Bagnato M, Donati D, Namia C, Novella L. Latent structure analysis of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 40:72–79. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC. The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illnesses, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:1660–1665. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, Olmstead ME, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1983;2:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman SJ, Dangelo EJ, Demaso DR. Psychopathology in the families of children and adolescents with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1832–1835. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.12.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Morey LC, Edelen MO, Shea MT, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH, Daversa MT, Gunderson JG, Zanarini MC, Markowitz JC, Skodol AE. A comparison of interview and self-report methods for the assessment of borderline personality disorder criteria. Psychological Assessment. 2008;20:81–85. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.20.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-case disorders: Findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Development and. Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen M, Karterud S, Pedersen G, Gude T, Falkum E. An investigation of the prototype validity of the borderline DSM-IV construct. Acta Psychiatrica Scandidavia. 2004;109:289–298. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0447.2003.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Burt SA. The Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR): Genetic, environmental and neurobiological influences on behavior across development. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9(6):971–977. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Age differences in genetic and environmental influences on eating attitudes and behaviors in preadolescent and adolescent female twins. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:239–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Chmielewski M, Miller CJ. The Reliability and Validity of Discrete and Continuous Measures of Psychopathology: A Quantitative Review. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:856–879. doi: 10.1037/a0023678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattanah JJF, Becker DF, Levy KN, Edell WS, McGlashan TH. Diagnostic stability in adolescents followed up to 2 years after hospitalization. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:889–894. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.6.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MN, Pumariega AJ. Eating disorders: Bulimia and anorexia nervosa. Clinical Assessment of Child and Adolescent Behavior. 2001;64:307–327. [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC. Classification of mental disorder as a collection of hypothetical constructs. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:289–293. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, Zanarini MC. Borderline personality: Traits and disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:733–737. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, Hopwood CJ, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Shea MT, Yen S, Stout RL, Zanarini MC, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH. Comparison of alternative models for personality disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:983–994. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins-Sweatt SN, Edmundson M, Sauer-Zavala S, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Widiger TA. Five-factor measure of borderline personality traits. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2012;94:475–487. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.672504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx: Statistical modeling. 5th ed. Charleston: Department of Psychiatry, Medical College of South Carolina; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Person Perception and Personality Pathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:32–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris J. Major theories of personality disorder. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1997;19:448–449. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Curtin JJ, Tellegen A. Development and validation of a brief form of the multidimensional personality questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:150–163. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pervin LA, John OP. Handbook of Personality. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology 1995. 1995;25:111–163. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel DB, Widiger TA. A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR personality disorders: A facet level analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1326–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Morey LC, Bender DS, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Stout RL, Zanarini MC, McGlashan TH. Confirmatory factor analysis of the DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: Findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):284–290. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Pane H, Ha C, Venta A, Patel AB, Sturek J, Fonagy P. Theory of Mind and Emotion Regulation Difficulties in Adolescents With Borderline Traits. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:563–573. e561. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Tests for Comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;87:245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Garvin V, Dohm FA, Rosenheck RA. Eating disorders in a national sample of hospitalized female and male veterans: Detection rates and psychiatric comorbidity. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1999;25:405–414. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199905)25:4<405::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks-Brown C, Durbin J, Burr R. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:235–253. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Widiger TA, Burr R. A structured interview for the assessment of the Five-Factor Model of personality: Facet-level relations to the axis II personality disorders. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:175–198. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Widiger TA, Lynam DR, Costa PT. Borderline personality disorder from the perspective of general personality functioning. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:193–202. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ranson KM, Klump KL, Iacono WG, McGue M. The Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey: A brief measure of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Eating Behaviors. 2005;6:373–392. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1988;54(1063) doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, Reynolds V. Axis II comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1998;39:296–302. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:274–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]