Abstract

Little is known about older African American women’s lived experiences with depression. What does depression mean to this group? What are they doing about their depression? Unfortunately, these questions are unanswered. This study examined older African American women’s lived experiences with depression and coping behaviours. The common sense model provided the theoretical framework for present study. Thirteen community-dwelling African American women aged 60 and older (M =71 years) participated. Using qualitative phenomenological data analysis, results showed the women held beliefs about factors that can cause depression including experiences of trauma, poverty, and disempowerment. Results also indicated the women believed that depression is a normal reaction to life circumstances and did not see the need to seek professional treatment for depression. They coped by use of culturally-sanctioned behaviours including religious practices and resilience. It appears these women’s beliefs about depression and use of culturally-sanctioned coping behaviours might potentially be a barrier to seeking professional mental health care, which could result in missed opportunities for early diagnosis and treatment of depression among this group. Implications for research, educational and clinical interventions are discussed.

Introduction

According to the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (20009), “depression is a medical condition that affects the body, mood, and thoughts. It affects the way one eats and sleeps. It affects how one thinks about things and one's self-perception. A depressive disorder is not the same as a passing blue mood. It is not a sign of personal weakness or a condition one can will or wish away. People with a depressive illness cannot merely “pull themselves together” and get better. Without treatment, symptoms can last for weeks, months, or years.”

Depression has been identified as a leading cause of disability in the United States, and worldwide. In fact, by 2020 depression is projected to be the number one cause of disability worldwide (World Health Organization [WHO], 2011). The disabilities include impairment in cognition, and ability to engage in activities of daily living (ADLs) such as adequate self-care, mobility, productivity, social activities and daily roles/routines (Williams et al., 2007). Given the negative impact of disabilities associated with depression, and the fact that depression is common among older adults (individuals 60 years and older) is cause for concern (Byers, Arean, & Yaffe, 2012).

For the purpose of this paper, older adults are defined as individuals 60 years and older. The prevalence of major depression among older adults ranges from 1% to 5% (Beekman, Copeland, Prince, 1999; Gallo & Lebowitz, 1999); however more recent data indicate an increase in prevalence of depression at 10% (Kessler et al., 2005). The prevalence of milder depression, in which symptoms are not as severe, but still impact ADLs range from 7% to 23% (Beekman, Copland, & Prince, 1999; Gallo, Lebowitz, 1999). Similarly, recent studies show that 13% to 27% of older adults (60 years and older) have subclinical depressions that do not meet the diagnostic criteria for major depression or dysthymia, but are associated with increased risk of major depression, physical disability, medical illness, and high use of health services (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2011).

Looking specifically at older African Americans, studies have shown varied prevalence rates ranging from 10 to 33% (Baker, Parker, Wiley, Velli, Johnson, 1999; Kurlowicz, Outlaw, Ratcliffe, & Evans, 2005). In particular, there appears to be disparities in prevalence of depression among older racial and ethnic minorities. A recent study indicated that elderly Hispanics (10.8% ) and African-Americans (8.9%) actually have higher rates of depression than their Caucasian (7.8%) counterparts.

The rates of depression among older African Americans may be complicated in part by symptom manifestation, symptom severity, culture/race, and age all of which are related to depression being underdiagnosed, misdiagnosed, or dismissed as a normal part of aging (Dunlop, Song, Lyons, Manheim, & Chang, 2003; Mills, Alea, Cheong, 2004; Skarupski, et al., 2005). For instance, common symptoms of depression include depressed mood most of the day, diminished interest or pleasure, suicidal ideations, significant weight loss or gain, insomnia, fatigue, and hopelessness (American Psychological Association [APA], 2000). However research suggests that older African Americans experience some of these common symptoms but they also self-report symptoms differently and report more disability. Gallo et al., (1999) found that although older African Americans compared to Caucasians reported less sadness or depressive symptoms, they were more likely to think about death. Another study showed African Americans reported experiencing more chronicity and disability associated with depression compared to Whites (Williams et al., 2007). Similarly, Warner and Brown (2011) found that among the elderly, African American women, and Latina had the highest disability levels compared to Caucasian women, and African American and Latino men.

The prevalence of depression is even more disconcerting among older African American women. A recent study examining depression in 150 older African Americans (75% of the sample was women) found the prevalence for depression was 30%, and 9% of the sample reported experiencing suicidal ideation (Kurlowicz et al., 2005). Skarupski et al., 2005, also found older African American women (21.3) evidenced more elevated depressive symptoms compared to their Caucasian counterparts (10.7). Research also suggests that older African Americans with multiple medical problems and decreased activities of daily living (ADLs) are at an increased risk of depression (Bazargan & Hamm-Baugh, 1995; Baker, Okwumabua, Philipose & Wong, 1996). In sum, this data seem to suggest that older African American women are at increased risk for depression, and they experience depression symptoms at severe levels.

Unfortunately, the increased vulnerability and disability associated with depression among older African American women is not matched by higher utilization of mental health services. Matthews and Hughes (2001), found that older African American women, compared to those under age 50, were less likely to be currently participating in therapy. Why are older African American women not seeking treatment for their depression? Is it possible that they may not be recognizing symptoms of depression? Some scholars contend that the expression of depression symptoms are culturally bound (Carrington, 2006; Waite, 2008) and relate to the lived experiences of the individual. However, very little research has examined older African American women’s lived experiences with depression. For instance, from a cultural perspective, how do these women make sense of depression? Are they aware of their depressive symptoms? And if so, what are they doing about their depression? Currently, these questions are unanswered in current aging and mental health literature.

To this end, the primary purpose of this qualitative phenomenological investigation was to examine older African American women’s lived experience with depression and their coping behaviours in response to depression. We used the Common Sense Model (CSM) to provide the theoretical framework for this study. The CSM is based in self-regulation theory, which suggest that illness representations or beliefs about an illness determine an individual’s appraisal of the illness as well as health behaviours including behaviours used to cope with the illness (Dieffenbachia & Eventual, 1996; Eventual, Neurons, & Steele 1984).

Methods

Phenomenology

Psychological phenomenology also known as transcendental phenomenology was used for this qualitative study. Transcendental refers to “everything is perceived freshly, as if for the first time” (Moustakas, 1994). There is less focus on the researcher (s) interpretations and more on a description of participants’ experiences. The goal of this approach is to describe and convey the “essence” of the experience as described by participants (Creswell, 2007). Transcendental phenomenology was chosen because the goal of this study was to examine older African American women’s lived experience with depression, with a focus on understanding and describing their subjective meanings of their experiences with depression. According to Polkinghorne (1989), phenomenology allows one to “understand better what it is like for someone to experience that” (p.46). To this end, transcendental phenomenology was instrumental to our goal of gaining a better understanding of what it is like for older African American women to experience depression.

Sample

Given that typical sample size in qualitative research is 10-15 individuals (Creswell, 2007), our goal was to recruit and enroll 13-15 study participants. Inclusion criteria were self-identified African American female, aged 60 years and older, and a score of 16 or higher on the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), which is indicative of depression. Exclusion criteria were presently experiencing suicidal ideation, and having an untreated alcohol or other drug problem; in which case referrals for additional care were provided. These exclusion criteria were used in an effort to reduce participation burden for individuals who were experiencing severe depression and too reduce the risk that our inquiry could increase emotional distress for participants. Also, the rational for excluding individuals with untreated alcohol or drug problem was due to interest in depression only rather than depression comorbid with alcohol or drug problems. Twenty-five individuals were screened for eligibility, of which 10 were screened out as they did not meet inclusion criteria, and 2 were lost before completion of data collection (interview). The total sample consisted of 13 older African American women (all community-dwelling), with a mean CES-D score of 24.5 indicative of moderate depression. Mean age of the sample was of 71 (range= 60-78 years). Mean number of children was four (range=0-16). Highest level of education completed was eighth grade and all participants were retired from the workforce.

Measures

Screening Measure

Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

The CES-D scale is a 20- item self-report inventory developed by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to assess the frequency and severity of depression symptoms in the past week (Radloff, 1977). The 20 items are scored 0-3, with a possible range of scores from 0-60, and a standard cut-off score of 16 has been defined as indicating depressive symptoms (Nguyen, 2004). A recent study examining measurement adequacy of the 20-item CES-D among community-dwelling African Americans aged 59 and older, found the Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable (0.86) and in our study it showed the same reliability (Long-Foley et al., 2002).

Demographic Measure

Demographic Questionnaire

Demographic information including age, education, income, marital status, health insurance status, employment status, type of housing, living arrangement, and years of residence in current city was collected.

Qualitative Interview

The women participated in a 60 to 75-minute, semi-structured, face-to-face interview designed to elicit candid responses about their experiences with depression. The interview started with a brief ice breaker to help participants feel comfortable and ease any anxiety (i.e. participants were asked about the weather or about their commute to the research office). Participants were then asked some of the following questions in the interview: What does depression mean to you? This first question provided the opportunity for participants to share their own perceptions about what depression meant to them and to share about their own lived experiences with depression. As the interview continued prompts were included such as, Tell me more about that? or Can you provide an example of that? To help participants provide more details about their experiences and extend the narrative, several follow-up questions were asked including: What do you think caused your depression? What did you do about your depression? and How do you think depression has affected your life? During the interview, if participants appeared to be in emotional distress they were offered the option to stop the interview and continue at another time. Fortunately, none of the participants exhibit emotional distress. Toward the end of the interview participants were asked if there were other information they would like to provide that was not asked earlier. Most of the participants shared that they appreciated the opportunity to participate in the study as they felt they were making a contribution to the African American society.

The interviews were conducted by two research assistants; both were African American female doctoral students. Racial matching of interviewers and participants was intentional to increase participants comfort and establish rapport and trust (Hamilton et al., 2006; Ward, 2005). Both interviewers participated in a 5-hour training, where they received a refresher in micro counselling skills including engaging in attentive listening, demonstrating empathy, and attending to any emotional distress exhibited by participants. They were also trained on the importance of creating a safe space for participants to feel comfortable, reassuring participants about confidentiality, being mindful of potential power dynamics and making efforts to equalize the relationship, and creating opportunities to ensure participants knew their contributions were valued and they were the experts. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by a trained transcriptionist. The primary investigator of the study checked each transcript against the audio recording for accuracy. All identifying information was removed from transcripts before analysis was conducted.

Procedures

Recruitment

Given that present study had a one-year timeline, the recruitment timeframe was 3 months, which then allowed the remaining 9 months to be used for data analysis and reporting of the study results to research participants and mental health agencies in the local community. . As African Americans historically have a low rate of participation in mental health research and due to the stigma associated with mental illness in the African American community (Ward, Clark & Heidrich, 2009; Ward & Heidrich, 2009), a number of recruitment strategies were employed: (a) flyers were posted at community agencies including local African American churches, senior housing facilities, and community centres; (b) advertisements were published in a local African American magazine; (c) meetings with pastors/leaders of local churches and directors of community agencies were scheduled to build community partnerships and publicize the study, (d) informing community stakeholders that anonymous study results would be presented to the local community, in an effort to increase awareness of mental illness and inform healthy coping behaviors. Also, a snowballing technique was implemented in which participants were encouraged to inform other women about the study. The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of a large university in the Midwest of the United States.

Data Collection

All of the participants signed a written informed consent to participate in the screening. Since none of the participants had ever participated in research, time was spent explaining the following: purpose of the study, benefits, risks, and confidentiality. In addition, the principal investigator’s contact information was provided. During screening, participants completed the CES-D and a short demographic questionnaire. Individuals who scored 16 or higher on the CES-D were invited to schedule a face-to-face interview. To enhance comfort levels and trust, participants were allowed to choose their interview location; some participants were interviewed in their homes and others in the researcher’s office. Of the 15 individuals who met study inclusion criteria, 13 agreed to participate in the interview and provided written informed consent. Two individuals declined participation in the interview due to health reasons.

After completion of the interview, participants were invited to participate in a debriefing session to give them an opportunity to process any emotional reactions to the interview, express concerns about their participation, or receive referrals for mental health counselling, if needed. None of the participants officially requested the debriefing session, but they all talked with staff casually after the interview about local and community events.

Data Analysis

To examine older African American women’s lived experiences with depression, thirteen transcripts made up the data for the qualitative analysis. The data was analysed by a team of three researchers, two of whom were skilled in qualitative research. A third team member was intentionally included who had little experience in qualitative and mental health research. Intentional inclusion of the third research member was designed to facilitate deeper curiosity with the data and challenge the research team to not take any data for granted and to engage in a more exhaustive analysis process. In addition, a research consultant who specializes in phenomenological research methodology was consulted.

Using phenomenological research analysis, texts were analysed to identify common meanings and the experience of living with depression. The first stage in the analysis involved having each team member independently read each transcript to obtain an overall understanding of the text. Second, the researchers used a process called horizontalization, in which each transcript was read a second time with the goal of highlighting significant statements, sentences or quotes that illustrated understanding of how participants experienced depression and what depression meant to them (Creswell, 2007; Moustakas, 1994). Third, each researcher prepared a written summary of each transcript with a description of what participants’ experienced (textural description) and a structural description, which is a description of the context or setting that, influenced how participants experienced depression (Creswell, 2007; Moustakas, 1994). Fourth, researchers met weekly and read their summaries aloud. They discussed themes from significant statements and quotes forming clusters of meaning and interpretations. The clusters of meaning identified appeared to show connections or relatedness. For example, several clusters began to emerge from the data that seemed to convey participants’ beliefs about “situations” they believed caused depression. Also, there seemed to be a connection between their beliefs of depression being normal with low treatment-seeking. After identifying connections between and among clusters, the team decided to create a model or visual representation of the clusters. Fifth, researchers both individually and collaboratively continued the process of forming clusters of meaning from significant statements and quotes and developing the visual representation of the clusters. The clusters of meaning process continued to the 13th transcript. Although data saturation was attained after the 10th transcript, to ensure we had truly attained saturation, data analysis continued until the 13th transcript. Sixth, using all of the textual and structural descriptions a composite description of participants’ experiences with depression, also known as the “essence” of their experiences with depression was written (Creswell, 2007). The composite description focused on the common experiences of the participants, in such a way that anyone reading it will feel like they “understand better what it is like” for older African American women to experience depression (Polkinghorne, 1989). The composite description was then depicted in a visual matrix to aid in visual representation of findings. Finally, the composite was written into a manuscript. The manuscript was then reviewed by the expert consultant in phenomenological research methodology and one research participant. All feedback was then incorporated in the present paper.

Several strategies were used to increase trustworthiness of the data analysis process and results. Bracketing was used throughout the analysis, which involved the research team setting aside their experiences with the study phenomenon (Creswell, 2007). In the present study, having a research team member with no experience in mental health enhanced the bracketing process. Specifically, this researcher regularly questioned the other two researchers to ensure that identified themes and interpretations were grounded in the data. Also, consulting with an expert in phenomenological research helped the research team stay true to phenomenological data analysis procedures. In addition, member checking, which involves having participants review the results to ensure it accurately reflected their experiences, was also conducted by one individual (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Results

The results of the qualitative analysis are presented using the following rubric of descriptors: “all” referred to responses from a sample of 13 participants; “majority” or “most” referred to responses from 10 or more participants; “some” or “several” referred to responses from 5-9 participants; and “few” referred to responses from 4 or fewer participants (Rhodes, Hill, Thompson, & Elliot, 1994; Sperber, Fassinger, & Prosser, 1997). In addition, results are presented using thick description (Ponterotto & Greiger, 2007). In qualitative research, use of thick description involves presenting detail, context, emotions, and social relationships, which help to establish the significance of the experience or phenomenon (Patton, 2002). In the present study, participants’ verbatim narrative (quotes) was used to provide thick description of the results. In presenting the findings of this study pseudonyms are used which allows readers to better understand and identify with participant responses and experiences.

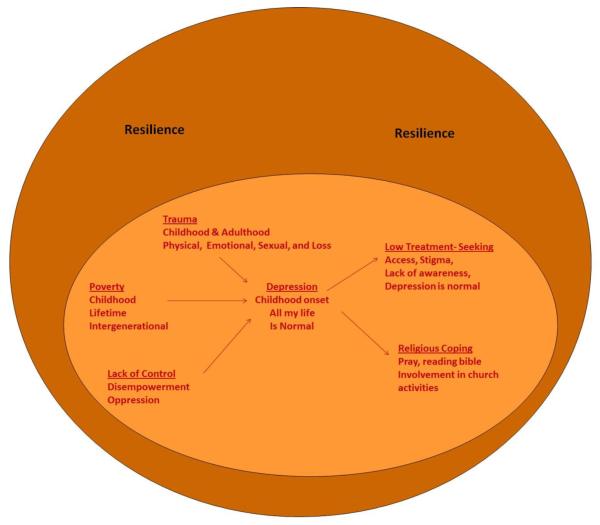

In examining older African American women’s lived experiences with depression; our findings suggested these older women believed they experienced a number of situations and events from childhood through adulthood that caused their depression. For most of the women, their depression developed in childhood and progressed through adolescence, young adulthood, and older adulthood. Due to chronic episodes of depression and intergenerational depression (generations of family members), the women believed depression was normal and in most cases they were unaware that they were experiencing depressive symptoms. Due to the women’s perceptions of depressive symptoms as normal and/or lack of awareness of the depressive symptoms, the women did not seek professional help. When they eventually sensed something was wrong, their primary modes of coping were using religious beliefs and practices (belief that God would take care of them, praying and Bible reading), and being resilient; which appeared to be culturally-sanctioned coping behaviours. The act of being resilient appeared to be imbedded in the women’s lives as a lifelong coping behaviour. A visual representation of these women’s lived experiences with depression was created to illustrate these women’s experiences in relations to their beliefs and coping. The components of the visual representation which form the core of the findings are discussed below (Also see Figure 1 for visual representation of the findings).

Fig. 1.

African American women’s lived experiences with depression and coping behaviours.

Beliefs about Causal Factors

Most of the women described a history of difficult life events that they believed contributed to their depression. Some of the traumatic events included the death of a parent or loved one, being abused physically, sexually, or emotionally, and being neglected. One participant shared she was never told of her mother’s death and so never truly understood that her mother was not coming back. As a child, she did not fully comprehend that she would never see her mother again, and her mother would never be there when she needed her to protect and keep her safe. After her mother’s passing she was sent to live with relatives where she was physically abused and often neglected. Ester, described her experience by stating,

Ester: Seems like when your mama closes her eyes (die), and you’re a kid, everybody’s mean and not very nice. You know, so that’s the way I took it. They (family) were mean, and they weren’t very nice. When my mother was alive, you didn’t notice all that, because they knew better. They couldn’t say or do things when my mama was there. Whereas, when she was gone, I had no backup.

Some of the women also experienced sexual trauma in childhood including rape and sexual molestation by male family members and other adults they knew and trusted. The women who were sexually abused in childhood received no professional mental health treatment, and in some case, no support from parents. As a result, they coped with the trauma on their own and in silence. Sofia stated,

Sofia: I had gotten raped. And they made him leave town. A woman relative called me up and told me I’d better leave town. She threatened me, but that didn’t bother me. And then to find out and I didn’t know this until years later, they had paid, gave money to my mother for me. I didn’t know that until years later… I got pregnant behind it, and they sent me back to my sister in (name of city). And that was like a treatment. I should’ve been getting real treatment, but it wasn’t nothing that came up about it.

Another woman shared her experience of neglect by her mother. Hattie Mae stated,

Hattie Mae: I had an accident my mother said, when I was a little less than two that damaged my right eye. But she never took me to a doctor, so my childhood wasn’t necessarily a good one. I guess it could’ve been worse because we were never hungry. You know, we always had a roof over our heads and adequate clothing and stuff. But no affection.

For most of the women, the trauma they experienced in childhood progressed into adulthood. They continued to struggle with loss of loved ones, family problems including worrying about their adult children, marital problems, and lack of social support from family. Georgia, Sue Ellen and Mary shared their experiences with these issues as described below.

Georgia: No, it (marital problems due to husband’s alcoholism) wasn’t healthy. But nobody knew it. Nobody knew that but me. I didn’t talk about it to the kids. I didn’t talk about it to my grandmother. I didn’t talk about it to my mother. And my mother died in the meantime. And that’s what hurt me a lot. Because I’d gotten to a point where I wanted to talk to her and that really hurt me that I didn’t have anybody to talk to. My grandmother was already dead. And then she (mother) died. She died suddenly. I mean, she was good one day, and the next day, she was gone. She was only 57.

Sue Ellen: Well, sadness, unhappiness, you know, I was sad and unhappy even before I lost my daughter. She was giving me so many problems from drugs, and then when she died, I was really depressed.

Mary: Well, I was depressed before. You have some friends that you think about. I felt that I had a lot of associates and friends, and that’s my trouble, people don’t have time for you. I have taken time and did so many things for other people, and it seemed like they were not there for me. Even my own relatives, I got sons and nephews, nieces, and not one called me after those three deaths, not even to ask, how I was doing, or if I was ok.

Poverty was another significant stressor most of these women experienced, which they believed led to their depression. They talked about being poor and experiencing hardships throughout their childhood and adulthood. The women also expressed a need to help family members who were struggling with poverty and difficult life events. The length of time these women struggled with poverty, and the need to help family members suggested poverty and hardships had a lifetime and intergenerational course in their lives. Sandy, and Sue Ellen said,

Sandy: I didn’t go to school, but maybe two or three days a week. And at that particular time, hot lunch at school wasn’t but $.05. And I couldn’t get $.05 for hot lunch. So I’d taken a biscuit with a piece of meat in it, and that’s what I had for my lunch.

Sue Ellen: When I was just starting high school, I had to take care of him (brother), which was so unfair. Then when I thought I didn’t have any more responsibility but myself, and was thinking about moving with my daughter, all of a sudden, I had him (brother) again.

The majority of the women also experienced many periods in their lives where they felt they had very little control over their lives. Due to the sexual trauma and other traumatic events they experienced, many of the women felt disempowered. In addition, lifelong struggles with poverty, going to prison, and living with an alcoholic and controlling husband left them feeling oppressed.

Sandy: This is what he did to control me; he made me feel like I wasn’t worthy. So I thought I wasn’t worthy. It wasn’t until I went back to school (college) in the ‘80s, because I went back after being out of school for 25 years. I went back to college. Well, I’m going to college, and so that’s when I started to kind of feel like I was worthy. And that’s when he really got crazy, because he realized, I wasn’t stupid after all. I wasn’t what he wanted me to be and I didn’t have to be under his control anymore. But as I think about it, he had made me feel like I wasn’t worthy…. That’s looking back now, you know. So I think that’s what caused that depression.

In summary, most of the women associated the origin of their depression to a difficult life event that occurred, for some as early back as their childhood. These women attributed their experiences with trauma and turmoil to their depression. Some of the traumatic events included the death of a parent or loved one, and being abused physically, sexually, or emotionally.

Beliefs about Depression

Most of the women reported a lack of awareness about depression. It was only in reviewing their lives and with recently acquired knowledge of depression that they were able to self-identify as depressed. Collectively, women reported not knowing they had depression, until the group meetings. Another participant also reported not knowing she was depressed, but was glad when she found out. She said, But I didn’t know, I didn’t know that I was depressed, but I was glad to know it. Another woman reported being prescribed an antidepressant by her primary care doctor, but she still did not realize she was experiencing depression or that the medication was prescribed to treat depression. Sofia said,

I just recently realized that’s what I was taking (name of medication) for, and it must’ve been depression. But I didn’t realize it at the time, because there were so many things, you know. I had already had five kids. And he (husband) was seven years older, and I guess that’s what (name of medication) was for. Why else would I be taking’ (name of medication)? You know, and I can’t remember if he told me it was for depression or not. I don’t remember. I really don’t. Like I said, I just recently realized that I had taken it, and so it must’ve been for that (depression).

For some of the women who developed depression in childhood, which continued into adulthood, they seemed to recognize the onset of their depression, and they believed they were depressed for a long time and possibly all of their lives. Hattie Mae shared,

Hattie Mae: I’ve always been depressed. I think I started being depressed when my mother passed. I was a kid and nobody explained anything to me. You know, back in those days, they kept everything to themselves. I have always been depressed, my whole life.

It appeared that due to the history of trauma, poverty, hardship, and feelings of disempowerment the women experienced throughout their lives, they believed chronic depression was a normal reaction to their circumstances. In addition, because many people around them including other family members and friends were also experiencing many of the situations and hardships associated with the onset of depression and were depressed, it reinforced the belief that depression was a normal reaction to their circumstances. For instance, one participant said, Well, it seemed like it has always been with me. Another woman shared her beliefs about the chronicity of her depression saying,

I don’t think anything can ever take away my depression, you know. It might not ever go away until I get to heaven, but I have better control over it, you know.

When asked what depression means to you, most of the women described how their lives had been changed by their depression. Sue Ellen said,

Sue Ellen: It means that I can’t live the life that I want to live. I can’t do the things that I feel that I should do. For example, my house is a disaster, and I always been much more of a tidy person. I know that I should do it, and I think about it, and I talk to myself about it. But it doesn’t get done. So that’s what it means to me, I’m not who I was before this experience of depression happened to me.

The women also shared what depression meant to them by describing symptoms of depression and how they believed the symptoms affected their ability to function. Their description of symptoms suggested they think of depression as a cluster of symptoms that negatively affected their ability to function normally. Some of the more commonly described symptoms included worry, loneliness, crying, lack of motivation, and difficulty concentrating. Mary and Jackie shared their symptoms saying,

Mary: Well, I just sat around and worried and sometimes cried. You know, I felt so alone; I felt like I didn’t have nobody.

Jackie: It (depression) really kind of messed up my life. You know, because I couldn’t focus enough, you know, to deal with somebody else and, you call yourself trying to be grown, you know. It was kind of hard.

In describing how depression has affected their ability to function normally, the women explained how they could not keep their regular routines (including going out with friends and relatives), feeling useless, and lack of motivation to get things done. Sandy and Marjorie said,

Sandy: And all day long I would get up and take my medication and sleep. I was diabetic by that time and I would get up and take my medicine, eat, go back to bed. If I stayed up very long, I would be crying. Sometimes she’d (Relative’s name) would say, get up, come on, we got to go someplace. You know, we ought to go to church, or we ought to just go someplace to get me out of the house.

Marjorie: My experience has been loneliness, not being involved with people, not figuring out a way to be useful, to involve myself with people, not wanting to go to the senior centre, where, well, there are just too many people there on walkers, and canes, and wheelchairs, and that wouldn’t work with my depression.

As indicated in this section, most of the women experienced depression without the awareness that they had the illness or how depression impacted their daily life. For many, the depression in their lives was only discovered with recently acquired knowledge which then allowed them to self-identify as depressed.

Low Professional Mental Health Treatment Service Use

The majority of women shared how they did not use professional mental health services for their depression. For the women who believed their depression started in childhood, they reported never receiving professional treatment. One woman reported being raped in childhood and in dealing with depression after the incident was never was taken to get treatment. Another woman discussed losing her mother at a young age and receiving no support from family, therefore getting professional treatment was not an available option. During childhood when the women had to rely on others or on adults to initiate treatment, the adults in their lives did not take them to treatment. As they became adults and continued to experience depression, most of them still did not seek treatment. The stigma associated with mental illness, denial about mental illness, lack of awareness, and the normalizing of mental illness appear to be barriers that affected the women’s interest and motivation to seek mental health services. Hattie Mae shared her concerns about stigma saying,

Hattie Mae: Who wants to talk about stuff like that? That’s embarrassing stuff. I was a career woman, okay. Anybody with any kind of decent reputation, I’m an accountant, and I’ve got clients, and many people under me, you know, and people looking up to me. Who wants to talk about something like that (depression)? I mean, it was degrading to me.

Georgia talked about her denial saying,

Georgia: I think sometimes I just didn’t try to really think, I didn’t want to think about it. I knew what was going on (depression), but I didn’t want to think about it. I didn’t want to think about what I needed to do and so I didn’t do anything, and that’s what caused it the second time I was in depression.

Of the 13 participants in the study, only three of them had previously sought mental health treatment; however, each reported treatment was not helpful. In particular, one woman discussed not understanding the role of her therapist, her own role in therapy, and was concerned about what her therapist thought about her. Mary said,

Mary: Yeah, I don’t know how much they are supposed to (do) as a therapist. I don’t know how much or how you should talk to that person. You know, I mean, it’s like, okay, she’s looking at the clock. Oh, your hour’s up. You know, that type of thing. So, I don’t know if she thought I was just rambling or what.

Another participant shared her experiences working with a Caucasian female therapist and expressed concern about whether her therapist sufficiently understood. Sofia said,

Sofia: So I think a female understands more. Even a White female will understand more as a therapist. And that’s what I had in (name of city). She was White, and I could talk to her. But I don’t think she was understanding. I don’t know if she was very understanding.

The women who sought treatment seemed to prefer working with African American therapists, but were not given that option. Sue Ellen said,

Sue Ellen: If she had been African-American, I think she would’ve understood. I mean, some things are just understood with us. You see what I’m saying?

The women also expressed concerns about psychotropic medication or psychotherapy (talk therapy). Sandy said,

Sandy: But I also talked to my Primary Care Doctor, who had talked to me about my condition (depression). And he prescribed some tablets for me to take, which were not good for me for a lot of reasons. So then, he recommended that I see somebody, and I’ve been seeing this woman, but I’m tired of talking. You know, you can only talk about how you feel so much.

In summary the majority of women in this study revealed that they did not utilize professional mental health services for their depression. This is an area in which the themes begin to overlap, given that these women reported a lack of awareness of depression it only makes sense that professional mental health would not be experienced as a viable source of support. Despite the difficult life events endured by many of the women, many did not receive any mental health services. Similarly, the stigma associated with mental illness, denial about mental illness, lack of awareness, and the normalizing of mental illness appear to be barriers that affected the women’s interest and motivation to seek mental health services. Although many of the women did not utilize professional mental health services, many reported coping with depression in other ways.

Culturally-Sanctioned Coping

Religious and Being Resilient

All of the women appeared to have a repertoire of coping strategies; however, religious coping and resilience seemed to be core culturally-accepted strategies. Religious coping included belief in God, prayer, Bible reading, consulting with clergy, and involvement in church activities such as Bible study, attending church services, and singing in the choir. The women believed religious coping helped their symptoms of depression. Georgia and Mary shared,

Georgia: So that just kind of reinforced the fact that God looks out for me, you know. He hears my prayers, and he’s concerned about me. So that has done more than anything to get my depression in check, you know.

Mary: It’s not that I don’t think about my loved ones (family problems). I do, but I don’t stay down there. Depression, I believe, is when you stay down there, and you can’t find your way up at all, you know. And that happened to me sometime, not recently, but it has happened, and it was only by the grace of God that I didn’t stay down.

Being resilient was the other core strategy used, and it appeared to be deeply imbedded in the women’s lives dating as far back as childhood. The use of resilience for these women involved having a belief that despite their circumstances or situation, they had to remain strong, live in the moment, and maintain a positive attitude. Below are quotes from Joy and Jackie that illustrate the role and importance of resiliency in their lives:

Joy: I have seen the hardship and sadness as a child on up, and still getting some headaches, you know what I mean. So it’s really hard. And actually, the more I talk about it, I feel like crying, but I don’t want to, I got to maintain.

Jackie: You know, life is beautiful, and life is what you make it, and I realize that now. You don’t have to be sad. If you are sad, it is because you wanna be. Because we do have a choice. We have a choice every day we wake up, and we could either choose to do good, be good, and do good things, or just sit and lay, and feel sorry for yourself. But I choose to be happy. I choose to do something good every day.

Further analysis of the participants’ culturally-sanctioned coping strategies (religious and resilience) suggested these strategies helped them function adequately; however, it may have masked their depression, thus, negating the need to seek professional help. Mary shared how religious coping has helped her to be happier by saying,

Mary: I’m probably happier now simply because I know the Lord, and he’s so comforting to me. I know some people don’t believe in heaven, but I absolutely do. And I know that I’m going to be in a better place than this, no aches or pains, you know. So, yeah, I look forward to that.

Sandy shared how she tried to commit suicide and God saved her life:

Sandy: Depression got me where I tried to commit suicide and when they got me to the hospital, there was nothing that they could do. They (doctors) said that she either lives or she dies. And God let me live and I said, ‘Well, it wasn’t for me to die.’ I might as well pick up the pieces and just keep right on going and I haven’t been back in the hospital. I get depressed, but it’s easier for me now to get over it because I know how to pray, and I know God will bring me out.

Further analysis revealed the women’s resilience helped them maintain a stable mood and function adequately day-to-day. One woman shared about trying to be stronger and needing to “let go” in an effort to cope with their depression.

Marjorie shared,

Marjorie: I said, ‘hmm, why don’t you try to forgive them, and let it go?’ And I’m finding it is not easy to forgive, but easier to let things go. I mean, nothing goes right like that (easily), like a blink of an eye. But when you start the process of letting things go, you start feeling better about yourself. You really do.

Other coping

In addition to the core coping mechanisms of religion and resilience, all of the women had other coping strategies. These included volunteering, social support from friends, staying busy, and keeping their mind occupied. Below, Joy, Hattie Mae, and Sandy describe their use of these strategies:

Joy: I’ve done a lot of volunteer stuff. I used to go, when Somerset closed down that year, I went with this lady. We worked together, got people homes to where they live, and work with the Housing Department. I was the president of that. I got on Oakland Coalition for the Elderly. I’m on the board there. So I’m very busy, and that helps me, because I have no time to think about myself.

Hattie Mae: I have a lot of stuff to keep me busy, and I do stay busy. But when I sit down and start thinking about my loved ones or even sit down here by myself, you know, it’s not good. I guess that’s the reason I stay busy, and I have to stay busy. My church keeps me busy.

Sandy: I’ve never felt to harm myself, thank God for that. But when I get like this (depressed), I try to do something and keep my mind occupied, you know. And I’m doing pretty well.

In summary the main culturally-accepted coping strategies expressed by these women were religious coping and resilience. As defined by these women, religious coping included belief in God, prayer, Bible reading, consulting with clergy, and involvement in church activities such as Bible study, attending church services, and singing in the choir. Intertwined with religious coping, the use of resilience for these women involved having a belief that despite their circumstances or situation, they had to remain strong, live in the moment, and maintain a positive attitude. Overall the women described religious coping and resilience as successfully helping them with their symptoms of depression.

Discussion

Research focusing on older African American women’s mental health is in an infancy stage; thus, there is a need for more research in this area. Findings from the present study make a contribution to this sparsely researched area, as well as informing clinical practice. In particular, the results of the present study provide a framework to better understand this group’s conceptualization of depression specific to their lived experiences with depression and their beliefs about depression. The findings also provides information about this group’s culturally- sanctioned coping behaviours in response to depression and how those coping behaviours influenced their use of mental health services. In addition, results of this study can inform future research with this group and guide development of educational and clinical interventions to better meet the mental health needs of older African American women with depression.

Study participants’ belief that depression is chronic (“all of my life”) is consistent with results of a national survey with a sample of 3,570 African Americans focusing on prevalence of depression among African American and Caucasians. Williams et al., (2007) found that the chronicity of major depressive disorder among African Americans (56%) was higher than for Whites (38.6%). Yet, Williams et al., (2007) did not examine differences in chronicity of depression by age group; therefore, the present study is probably the first to document that older African American women reported experiencing chronic depression. Additionally, Kessler et al. (1997) found that adults who suffer from mental disorders were more likely to report having been exposed to serious hardships during childhood, which again provides evidence for the chronicity of depression in this group. Also, given that unidentified and untreated depression increases risks for morbidity and mortality among older adults (Lesperance, Frasure-Smith, Talajic, & Bourassa, 2002; Matthews & Highes, 2001), results of the present study underscore the critical need for early identification and treatment of depression among older African American women.

Participants’ beliefs about causal factors of depression are consistent with causal factors identified in the Diagnostic Statistical Manual- IV-TR (APA, 2000) and in the social determinants of health literature (Buckner-Brown et al., 2011), suggesting they have reasonably accurate knowledge of factors that cause depression. Yet, the findings indicated participants’ accurate knowledge of causal factors and their self-knowledge of experiencing many of the casual factors did not translate into self-identification of depression or seeking professional mental health services. A number of factors might explain these participant’s inability to connect causal factors with self-identification of depression and the need for professional treatment, including: 1) some women lacked awareness about depression and depression symptoms; 2) perception of depression as normal given their life circumstances (trauma, loss, poverty, disempowerment); 3) lack of knowledge about what to do about depression, and 4) reluctance to admit being depressed due to the stigma associated with depression.

Surprisingly, several of the women in present study perceived depression as normal or a normal reaction given their life struggles including a history of disempowerment, poverty, trauma, and loss. Their perception of depression as normal is disconcerting because these women are suffering unnecessarily. Furthermore, it is possible their perception of depression may actually serve as a barrier to seeking professional mental health care. However, the present study results do not provide definitive conclusions about relationships between perceptions of depression and treatment-seeking behaviours. Such research is critically needed.

Findings suggested all of the women endorsed use of culturally-sanctioned coping behaviours such as religious coping and resilience. There is literature showing that religious coping is very common among African Americans including older African American women, and it may be protective (Cooper, Brown, Ford, & Powe, 2001; Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990; Taylor, Chatters, & Joe, 2011). The research participants’ use of resilience is consistent with the resilience literature. According to Smith (2009), resilience is the ability of an individual or group to carry on and solve problems so that survival of hard times is more likely. In addition, resilience involves personal coping behaviours that help individuals survive and thrive despite adversity or misfortune (Connor, 2003). Resilience is also believed to be protective (Edward, 2005). In contrast, results of the present study suggested some of these women continued to experience depression despite high use of religious coping and resilience. This raises three critical questions: Are religious coping and resilience protective? Also, can religious coping and resilience mask depression? Is use of religious coping and resilience a barrier to seeking professional mental health treatment among this group? As recent research indicates older African Americans are less likely than others in their age cohort to be diagnosed with or treated for depression (Cooper et al., 2003; Gallo et al., 2005), it is possible religious coping and resilience may mask symptoms of depression resulting in delayed treatment-seeking or no treatment-seeking. It may also foster the belief that professional treatment is not needed. These unanswered questions underscore the need for research examining the influence of culturally- sanctioned coping on treatment-seeking among African Americans using a life course perspective to determine differences by age cohort and gender.

The present study is not without limitations. The first limitation revolves around difficulties in recruiting older African American women with symptoms of depression. To overcome this issue a “snowballing” approach was used. The recruitment strategy of snowballing invites study participants to share information about the study with others to increase recruitment (Karasz, 2005). While increasing recruitment, this approach may have increased the homogeneity of the sample and decreased opportunities to identify differences in beliefs and coping behaviours. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits the ability to determine changes in beliefs/perceptions and coping behaviours over time. Third, the exploratory nature of the study limits inferences about casual relationships among the constructs of interest (i.e. relationships between perceptions of depression and treatment-seeking). Four, although our finding regarding use of culturally-sanctioned coping is important, it may also be limited to only the sample studied, thus affecting transferability (generalizability). Finally, as the study was conducted in one geographic region, the transferability of the study findings might be impacted. However, the purpose of phenomenology research is to better understand what it is like for certain groups to experience a particular phenomenon which was accomplished in the present study. Despite these limitations, the study results can inform future research and clinical practice.

Future Research and Clinical Implications

Research

Given that our findings appear to suggest connections or relatedness in beliefs about causal factors and preferred coping, future research using quantitative methodology could examine whether beliefs about causal factors predict coping behaviors.

The few participants in the study who sought professional mental health services expressed dissatisfaction with the quality of care and expressed a need to be matched with African American clinicians. Thus, there is a need for research focused on developing and testing culturally-specific depression interventions designed to treat depressive symptoms among older African American women. In addition, given the high use of religious coping, research using community-based participatory research approaches could focus on the use of clergy and parish nurses in increasing awareness of mental illness and encouraging timely and appropriate treatment-seeking behaviours. Also, if the stigma associated with mental illness makes it challenging to recruit participants for mental health research, it is even more challenging to recruit older adults due to mobility limitations and poor health. Therefore, it is no surprise that research focusing on mental health needs of older African Americans is in an infancy stage. There is a need for research to examine and identify recruitment strategies to increase inclusion of older African Americans in mental health research. Nurses are in a unique position to conduct research and provide clinical care in this area, as they work with a large number of older individuals due to the increasing aging population in the U.S. and the increasing disability among this group (Byers, Arean, & Yaffe, 2012; WHO, 2011).

Clinical

Findings from the present study raise concerns about whether culturally-sanctioned coping strategies such as religious coping and resilience may mask depression; if so, there is a need to increase identification and treatment of depression among this group. One opportunity to address this issue is having nurses and primary care physicians (PCP) routinely inquire about risk factors and symptoms of depression during medical assessments. Aslo, race and gender of medical staff might be important to older African American women, thus having female nurses of the same race conduct routine assessments during medical visits can be helpful. Such an approach could communicate to older African American women that their mental health is not a separate issue from their physical health and thereby reduce stigma and embarrassment (United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2001). Moreover, in an effort to provide more culturally sensitive care, psychiatric nurses and parish nurses could explore opportunities to partner with clergy and health ministries in African American churches to provide outreach to older African American women. Such a partnership could involve having regular mental health fairs or mental health workshops at churches, conducting depression screening, and providing information about treatment options and community resources.

Conclusion

The study results showed participants held beliefs about causal factors for depression; and believed depression is a normal state. Such beliefs among this group appear to result in low use of mental health services, and high reliance on culturally-sanctioned coping including religious coping and resilience. Although the women’s beliefs about causal factors are consistent with the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria (APA, 2000) used to identify depressive symptoms, their beliefs did not translate into self-identification of depression or treatment-seeking. The findings raise a critical future research question; are these women’s culturally-sanctioned coping behaviours masking their depression? In summary, results of the present study have critical future research and clinical implications including: (1) the need to increase research focusing on the mental health needs and care of older African American women; (2) the need for health care providers to make depression screening part of routine health assessments; and (3) the need for mental health clinicians to partner with African American churches to reach older African American women experiencing depression.

References

- Alvidrez J, Azocar F. Distressed women’s clinic patients: Preferences for mental health treatments and perceived obstacles. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1999;21:340–347. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(99)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.; Arlington:VA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baker FM, Okwumabua J, Philipose V, Wong S. Screening African American Elderly for the Presence of Depressive Symptoms: A Preliminary Investigation. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 1996;9(3):127–132. doi: 10.1177/089198879600900304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker FM, Parker DA, Wiley C, Velli SA, Johnson JT. Depressive symptoms in African-American medical patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1995;10:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Beekman AT, Copland JRM, Prince MJ. Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;197:307–311. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner-Brown J, Tucker P, Rivera M, Cosgrove S, Coleman JL, Penson A, Bang D. Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health: Reducing Health Disparities by Addressing Social Determinants of Health. Family & Community Health: Journal of Health Promotion & Maintenance. 2011;34:S12–S22. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318202a720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan M, Hamm-Baugh VP. The Relationship Between Chronic Illness and Depression in a Community of Urban Black Elderly Persons. Journal of Gerontology Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1995;50B(2):S119–S127. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.2.s119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers BL, Arean PA, Yaffe K. Low use of mental health services among older Americans with mood and anxiety disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(1):66–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington CH. Clinical Depression in African American Women:Diagnoses, Treatment, and Research. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:779–791. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski PS, Katon w.J., Russo JE. Depression and diabeters: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Archeive of Internal Medicine. 2000;160:3278–3285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Brown C, Vu HT, Ford DE, Powe NR. How Important Is Intrinsic Spirituality in Depression Care? A Comparison of White and African-American Primary Care Patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:634–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Gonzales J, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith L, Rubenstein L, Wang N, Ford ,D. The Acceptability of Treatment for Depression Among African-American, Hispanic, and White Primary Care Patients. Medical Care. 2003;41:479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KMD, J RT. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depression and Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Sage Publication; Thousand Oaks: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan HS, Ward SE, Song M, Heidrich SM, Gunnarsdottir S, Phillips CM. An update on the representational approach to patient education. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2007;39:259–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diefenbach MA, Leventhal H. The common-sense model of illness representation: Theoretical and practical considerations. Journal of Social Distress & the Homeless. 1996;5:11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop DD, Song J, Lyons J, Manheim L, Chang R. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Rates of Depression Among Preretirement Adults. American Journal of Public Health and the Nations Health. 2003;93(11):1945–1952. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edward KL. Resilience: a protector from depression. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2005;11:101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Lebowitz BD. The epidemiology of common late-life mental disorders in the community: Themes for the new century. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:1158–1166. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Straton JB, Margo K, Lesho P, Rabins PV, Ford DE. Patient characteristics associated with participation in a practice-based study of depression in late life: The Spectrum study. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2005;35:41–57. doi: 10.2190/K5B6-DD8E-TH1R-8GPT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton LA, Muktar HA, Lyons PD, May R, Swanson CL, Savage R, et al. African American community attitudes and perceptions toward schizophrenia and medical research: An exploratory study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98:18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalance and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comobidity survey replication. Archieve of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–768. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS. Childhood adversity and adult psyhiatric disorder in the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:1101–1119. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurlowicz LH, Outlaw FH, Ratcliffe SJ, Evans LK. An exploratory Study of depression among older African American Users of an academic outpatient rehabilitation program. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2005;19:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Five-year risk of cardiac mortality in relation to initial severity and one-year changes in depression symptoms after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105:1049–1053. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Nerenz DR, Steele DJ. Illness representations and coping with health threats. In: Baum A, Taylor SE, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of psychology and health: Social psychological aspects of health. Earlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln E, Mamiya L. The Black Church in the African American Experience. In: Lincoln YS, Guba EG, editors. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1990. 1985. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Long-Foley K, Reed P, Mutran EJ, Devellie RF. Measurement adequacy of the CES-D among a sample of older African-Americans. Psychiatry Research. 2002;109(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AK, Hughes TL. Mental health service use by African American women: Exploration of subpopulation differences. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7:75–87. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills TL, Alea NL, Cheong JA. Differences in the indicators of depressive symptoms among a community sample of African-American and Caucasian older adults. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004;40:309–331. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000035227.57576.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas C. Phenomenological Research Methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Heealth [NIMH] Older adults and depression. 2011 Retrieved June 1, 2011 From http://alcoholism.about.com/library/blnimh13.htm.

- Office of the Surgeon General (US) Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Centre for Mental Health Services; National Institute of Mental Health (US). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation. 3rd Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie KJ, Jago LA, Devcich DA. The role of illness perceptions in patients with medical conditions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007;20:163–167. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328014a871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne DE. Phenomenological Research Methods. In: Valle RS, Halling S, editors. Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology. Plenum; New York: 1989. pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ponterotto JG, Grieger I. Effectively communicating qualitative research. Counseling Psychologists. 2007;35:404–430. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes RH, Hill CE, Thompson BJ, Elliot R. Client retrospective recall of resolved and unresolved misunderstanding events. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1994;41:475–483. [Google Scholar]

- Skarupski KA, Mendes de Leon CF, Bienias JL, Barnes LL, Everson-Rose SA, Wilson RS, et al. Black-White differences in depressive symptoms among older adults over time. Journals of Gerontology. 2005;60:136–142. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.3.p136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PR. Resilience: resistance factor for depressive symptom. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2009;16:829–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber Richie B, Fassinger RE, Prosser J. Persistence, connection and passion: A qualitative study of the career development of highly achieving African American-Black and White women. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1997;44:133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Joe >Sean. Non-organization religious participation, subjective religiosity, and spirituality among older African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Journal of Relgion and Health. 2011;50:623–645. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite RK,P. Health beliefs about depression among African American women. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2008;44(3):185–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2008.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward EC. Keeping it real: A grounded theory study of African American clients engaging in counseling at a community mental health agency. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:471–481. [Google Scholar]

- Warner DF, Brown TH. Understanding how race/ethnicity and gender define age-trajectories of disability: An intersectionality approach. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;72:1236–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Gonzalez H, Neignbors H, Nesse R, Abelson, Sweetman J, Jackson J. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization [WHO] Depression Facts and Statistics. 2011 Retrieved June 1, 2011 from http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/definition/en/