Abstract

Despite decades of research on cerebral malaria (CM) there is still a paucity of knowledge about what actual causes CM and why certain people develop it. Although sequestration of P. falciparum infected red blood cells has been linked to pathology, it is still not clear if this is directly or solely responsible for this clinical syndrome. Recent data have suggested that a combination of parasite variant types, mainly defined by the variant surface antigen, P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1), its receptors, coagulation and host endothelial cell activation (or inflammation) are equally important. This makes CM a multi-factorial disease and a challenge to unravel its causes to decrease its detrimental impact.

Keywords: cerebral malaria, endothelium dysfunction, inflammation, histopathology, PfEMP1

Introduction

Malaria

Malaria is a devastating infectious disease with an estimated 207 million cases and 627,000 deaths, mainly in children under 5 years of age in sub-Saharan Africa, in 2012 (World Health Organization, 2013). It is caused by the Apicomplexan parasite Plasmodium, of which P. falciparum is the most deadly of the species. Its asexual replication in the red blood cells (RBC) causes the pathology of the disease and during development it also modifies the host cell (White et al., 2014). In the trophozoite-stage, parasite proteins are exported to the surface of the RBC where they play a role in immune recognition and adherence to host endothelium (Kraemer and Smith, 2006; Chan et al., 2012; Craig et al., 2012a; Beeson et al., 2013), as well as other interactions with host cells (Pain et al., 2001; Fernandez and Wahlgren, 2002; Rowe et al., 2009). These parasite-host interactions are associated with the pathology of malaria and contribute to the development of severe malaria (SM). SM is defined by WHO as severe anemia, respiratory distress (or lactidosis) or coma, or a combination of these (Idro et al., 2005; Perkins et al., 2011; Shikani et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2012). Most people suffer from uncomplicated malaria with only fever as a symptom, besides the presence of falciparum parasites in their blood. Many adults in endemic countries will encounter asymptomatic malaria, in which the infection is rapidly cleared by the host's immunological responses against the P. falciparum infected RBC (iRBC). However, only repeated P. falciparum infections give protection from disease, with sterile, anti-parasite immunity rarely achieved (Liehl and Mota, 2012; Spence and Langhorne, 2012; Portugal et al., 2013; Riley and Stewart, 2013).

Cerebral malaria

Approximately 1% of P. falciparum infections results in CM with 90% of these cases in children in sub-Saharan Africa (W. H. World Health Organization, 2013). In adults in South-East Asia, CM accounts for 50% of the malaria deaths, as they not only suffer from encephalitis but also have multiple organ failure, which is absent in pediatric CM (Idro et al., 2005). More recently there has been an awareness of the burden of varying neurological deficit in survivors (Birbeck et al., 2010), increasing the impact on fragile economies. CM is clinically defined as having P. falciparum parasitaemia and unrousable coma, ruling out any other cause of coma, such as meningitis. Coma is assessed by verbal and motor responses and rated on either the pediatric Blantyre Coma Score (1 or 2 on a scale of 5) (Molyneux et al., 1989) or Glasgow Coma Score (<11 on a scale of 15) for adults (Teasdale and Jennett, 1974). Mortality is 15–20%, but 10–20% of survivors suffer from long-term neurological sequelae (Birbeck et al., 2010). The ultimate diagnosis is post-mortem through detecting brain hemorrhages and lesions in the brain with sequestered iRBC in the microvasulature. In a study of Malawian children clinically diagnosed with CM, 23% died of other causes than malaria (Taylor et al., 2004), demonstrating the difficulties faced by clinicians operating in an environment with a broad spectrum of severe disease.

The etiology of CM is not known. Although clearly linked to higher parasitaemias, these are not a prerequisite of CM (Gravenor et al., 1998) and it has been difficult to attribute specific parasite traits to the disease. Indeed, there has been considerable discussion about the relative roles of inflammation and cytoadherence (Berendt et al., 1994a; Clark and Rockett, 1994a,b; Ponsford et al., 2012; Cunnington et al., 2013a,b; Hanson et al., 2013; White et al., 2013), with both factors probably playing a role with varying influences in what is a variable clinical presentation (Grau and Craig, 2012). What does appear to be common is the presence of sequestered iRBC in the brains of people dying from this disease, although this does rely on post-mortem examination and therefore excludes observations on the majority of cases. In part this has been addressed by retinal examination (White et al., 2001; Maude et al., 2009), which provides a sensitive and specific indication of CM based on abnormal retinal characteristics that reflect some of the cerebral pathology and can therefore discriminate between coma caused by CM or other causes (MacCormick et al., 2014). Experimental CM, in which a P. berghei infection in mice causes CM, is frequently used to dissect the pathogenesis of CM. However, prominent sequestration of iRBC in the brain vasculature is not present and inflammatory processes are the main manifestation (de Souza et al., 2010; Craig et al., 2012b; Hansen, 2012). These studies are not included in this review, but they are discussed in two recent reviews on CM (Grau and Craig, 2012; Shikani et al., 2012).

Pathogenesis of CM

Histopathology studies

Sequestration of iRBC in the brain microvasculature is a hallmark of CM, with all autopsies showing the presence of iRBC causing congestion in the venules and capillaries, but sequestration is also detected in the brains of malaria patients who died of non-CM causes (NCM) (MacPherson et al., 1985; Maneerat et al., 1999; Taylor et al., 2004; Dorovini-Zis et al., 2011). However, the levels of sequestration and the percentage of sequestered vessels are significantly higher in the brains of CM sufferers and correlate to disease severity for both adults and children (MacPherson et al., 1985; Riganti et al., 1990; Maneerat et al., 1999; Dorovini-Zis et al., 2011; Ponsford et al., 2012). Sequestration is also detected in the lung, heart, kidney, skin and intestine and again this is higher in CM compared to NCM, but it is not as prominent as in the brain (MacPherson et al., 1985; Pongponratn et al., 1991; Seydel et al., 2006; Milner et al., 2013). The iRBC adhere to endothelium and the majority of P. falciparum are in the trophozoite or schizont stage, when they express parasite proteins on the surface of the RBC, such as the variant surface antigen PfEMP1.

In adults, cerebral sequestration is correlated with coma and earlier death, and it has been suggested that microvascular obstruction is key to the pathogenesis of coma (Ponsford et al., 2012). The main cause of coma is not known, and besides obstruction, a range of other mechanisms have been postulated, as reviewed by Idro et al. and Postels et al. (Idro et al., 2005; Postels and Birbeck, 2013). In pediatric CM, sequestration of iRBC is mostly (but not always) associated with microvascular pathology as demonstrated by endothelial damage and perivascular ring hemorrhages (Dorovini-Zis et al., 2011). Monocytes with malaria pigment and fibrin–platelet thrombi were also associated with iRBC sequestration and contribute to congestion (Dorovini-Zis et al., 2011). Whether these immune cells also contribute to microvascular congestion in adult CM is questionable (see section below), but obstruction by uninfected RBC has been detected in adult brain (Ponsford et al., 2012). Overall, microvascular congestion seems to leads to severe endothelial damage, causing disruption of the vessel wall, resulting in myelin and axonal damage and breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (Brown et al., 1999; Dorovini-Zis et al., 2011). However, impairment of the BBB does not seem to occur to the same extent in adults (Medana and Turner, 2006; Renia et al., 2012; Polimeni and Prato, 2014), which could be due to the ongoing brain development in young children, which would make the BBB more susceptible (Hawkes et al., 2013).

What is the primary cause of CM?

Whether sequestration, and therefore congestion, is the main cause of coma and CM has been debated for decades (Berendt et al., 1994b; Ponsford et al., 2012; Cunnington et al., 2013b; Hanson et al., 2013; White et al., 2013). The “school of sequestration” argue that:

The amount of sequestration and congestion correlates with disease severity.

Lactate production by anaerobic glycolysis, because of obstruction, is also correlated to the severity of the disease.

Impaired cytoadherence because of abnormal PfEMP1 distribution and reduced PfEMP1 expression on iRBC in haemopathies causes protection against severe disease (Fairhurst et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2013).

Adjunctive therapies based on alternative causes of CM, like cytokine activation or hypovolemia, have not been proven effective (see table in White et al., 2013).

In contrast, the “school of cytokines” (Clark and Rockett, 1994a,b; Clark and Alleva, 2009) argue that:

Although P. vivax does not sequester in the microvasculature, it causes endothelial activation (Yeo et al., 2010) and encephalopathy and coma in children (Manning et al., 2012).

Healthy, malaria-tolerant children with high parasitaemia cannot reasonably be said to have parasites clogging their cerebral blood vessels (Clark and Alleva, 2009).

Pro-inflammatory TNF is associated with disease severity and is the main cytokine involved in CM.

Point (3) for the cytokine hypothesis is questionable with some studies showing a clear increase in TNF in CM, which is even higher in fatal cases in African children (Grau et al., 1989; Kwiatkowski et al., 1990; Sahu et al., 2013), but more recent studies have shown no correlation between TNF concentration and CM (Esamai et al., 2003; Armah et al., 2007; Thuma et al., 2011). Other cytokines have been implicated too (Hunt and Grau, 2003; Boeuf et al., 2012; Ioannidis et al., 2014), but the results of these studies are hard to interpret as it depends on which control group it is compared to; NCM, severe malarial anemia, other encephalitis, other febrile illnesses or even healthy individuals. In addition, patients often have other infections, especially African children, so the cytokine profile may not be a full reflection of the Plasmodium component of infection. The same is the case for the presence and role of immune cells in the cerebral vasculature. In post-mortem brain sections, sometimes neutrophils are seen (MacPherson et al., 1985), lymphocytes (Patnaik et al., 1994), monocytes/macrophages (Patnaik et al., 1994; Maneerat et al., 2000; Dorovini-Zis et al., 2011), or platelets (Pongponratn et al., 1985; Grau et al., 2003; Dorovini-Zis et al., 2011). These discrepancies in clinical observations may be the result of which part of the brain is used; cortex, cerebellum, brain stem, white or gray matter, how many hours after death the brain was sampled or to which control group the brain sections are compared.

Although the primary event in the development of CM still unknown, it is evident from recent work that endothelial activation plays a major role in the pathogenesis; whether this is caused by iRBC, parasite proteins (released after rupture of the RBC) (Gillrie et al., 2012), inflammatory cytokines or a combination of all of them is less clear.

Endothelial dysfunction

Endothelial activation can be characterized by markers such as von Willebrand factor (Hollestelle et al., 2006), angiopoietein-1 and -2 (Lovegrove et al., 2009), and soluble endothelial receptors (Turner et al., 1998). Angiopoietein-1 stabilizes endothelium and angiopoietein-2 is its antagonist and is released by endothelial cells upon inflammatory stimuli and induces vascular permeability and up-regulation of endothelial receptors. Decreased Ang-1 or increased Ang-2 levels in serum, as measured by an increasing Ang-2/Ang-1 ratio, is associated with CM and can predict disease severity in adults and children (Conroy et al., 2009, 2010; Lovegrove et al., 2009; Jain et al., 2011; Prapansilp et al., 2013). Ang-1 and Ang-2 are regulated by nitric oxide, a signaling molecule in many processes, which is produced in the endothelium from L-arginine and causes vasorelaxation, vascular quiescence, down-regulation of endothelial adhesion molecules and reduces thrombosis (Bergmark et al., 2012). Nitric oxide bio-availability is reduced in SM and relates to fatal outcome and several groups have suggested that this could be linked to low L-arginine levels during malaria infection (Anstey et al., 1996; Lopansri et al., 2003; Yeo et al., 2007, 2008). Other markers of endothelial activation have been investigated, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, but the outcome is not always consistent between adults and children (Kim et al., 2011; Canavese and Spaccapelo, 2014).

Activated endothelium also over-expresses some of its receptors, which are subsequently shed into the plasma. P. falciparum infection up-regulates ICAM-1, V-CAM and E-selectin on cerebral microcvascular endothelium and some of these (e.g., ICAM-1) are co-localized with iRBC sequestration (Turner et al., 1994; Armah et al., 2005). However, there does not seem to be a specific correlation with CM as patients with uncomplicated malaria also have activated endothelium, although to a lesser extent (Turner et al., 1998; Rogerson et al., 1999). Unexpectedly, activation and systemic inflammation lasted for 4 weeks after diagnosis for all malaria cases, as measured by soluble ICAM-1, angiopoietein-2 and C-reactive protein (Moxon et al., 2014). Soluble ICAM-1 does seem to correlate with CM (Adukpo et al., 2013), but depending on the comparator control group (UM or other SM) it seems more strongly associated with SM (Cserti-Gazdewich et al., 2010; Erdman et al., 2011). Circulating endothelial microparticles are also associated with SM only in adults (Sahu et al., 2013) but do correlate with CM in children (Combes et al., 2004).

Endothelial dysregulation plays a role in the pathogenesis of SM, but this seems to be a general effect and is not confined to cerebral tissue alone. One of the problems in investigating vascular inflammation has been the difficulty in accessing cerebral tissue. Surrogate tissue, such as subcutaneous fat, has been used successfully to investigate microvascular endothelium (Wassmer et al., 2011; Moxon et al., 2013). This is easily obtained by biopsy and has some, but certainly not all, features of brain endothelium. These studies have shown that endothelial cells from children with CM show increased responsiveness to TNF and that the endothelium is changed by the presence of adherent iRBC, removing important control proteins involved in the coagulation/inflammation pathways.

A useful non-invasive tool in the clinical diagnosis of CM is retinopathy, in which the eye is used as a window into the brain. Sequestration and vascular damage can be visualized in the retina and the degree of damage correlates with the severity of microvascular brain damage and is a predictor of death (White et al., 2001; Maude et al., 2009; Beare et al., 2011), as is recently reviewed by MacCormick et al. (2014) The severity of retinopathy is also predictor for the neurocognitive problems that pediatric CM survivors suffer after recovering (Boivin et al., 2011).

The role of the parasite

Why does sequestration of iRBC lead to vascular dysfunction in the brain? Sequestration of iRBC is also observed in other organs, but there seems to be no associated pathology. In CM, sequestration is the highest in the brain, but gastrointestinal and pulmonary sequestration is also present and in some cases very high. Unfortunately, not much histopathology has been performed on these tissues, but in pediatric CM only parasite sequestration and no other phenomena in the lungs was associated with CM (Milner et al., 2013). Furthermore, no hemorrhages, necrosis, abnormal architecture or inflammatory cells were detected in the gut (D. Milner, personal communication). Thus, do localized inflammatory responses to a P. falciparum infection have much greater effect on the cerebral vasculature? Or does the parasite itself play a significant role in combination with the host response?

Multiple P. falciparum genotypes are present in the human host, but only a subset of these sequester in the brain (Montgomery et al., 2006). Cytoadherence of iRBC to endothelial cell receptors is mediated by PfEMP1, one of the variant surface antigens of Plasmodium falciparum (Scherf et al., 2008; Pasternak and Dzikowski, 2009). Classification of the protein structure has recently been based on “domain cassettes” (DC), made up from combinations of the PfEMP1 Duffy Binding like (DBL) and Cysteine rich interdomain region (CIDR) subdomains (Rask et al., 2010). These DCs, along with other sequence signatures [e.g., PoLV (Bull et al., 2008)], have been associated with specific clinical outcomes, suggesting that particular domains of PfEMP1 play a role in pathology (Warimwe et al., 2012). Variants containing the conserved DC8 and DC13 are associated with SM in children (Claessens et al., 2012; Lavstsen et al., 2012) and are the main variant in parasites of children with CM in Benin (Bertin et al., 2013). The variants were identified by in vitro cytoadherence assays to human brain microvascular endothelial cells (Avril et al., 2012; Claessens et al., 2012), but they also bind avidly to endothelial cells of lung, heart and bone marrow, suggesting a common receptor (Avril et al., 2013). The PfEMP1-DC8 receptor was identified as Endothelial Protein C Receptor (EPCR) on brain endothelium and binding to EPCR, as well as ICAM-1, was shown to be associated with SM, including CM (Turner et al., 2013). ICAM-1 has long been implicated as an endothelial receptor in the brain and is associated with CM in some studies (Turner et al., 1994; Ochola et al., 2011). Recently, seven new receptors for PfEMP1 were identified that seem to be expressed on brain endothelium, but no correlation with disease severity has been shown yet (Esser et al., 2014).

In binding to EPCR the iRBC blocks the conversion of inactive protein C to activated protein C, potentially contributing to localized endothelial activation. In a separate study it was shown that adhesion of iRBC to endothelium reduced the levels of EPCR and its coagulation partner thrombomodulin on endothelium and suggested that the relatively low expression of these receptors on brain endothelium compared to other tissues would make the brain particularly susceptible to inflammation caused by reduced control of thrombin production. Taken together both of these studies suggest an important role for localized coagulation/inflammation related pathology in CM. (Moxon et al., 2013; Aird et al., 2014; Angchaisuksiri, 2014).

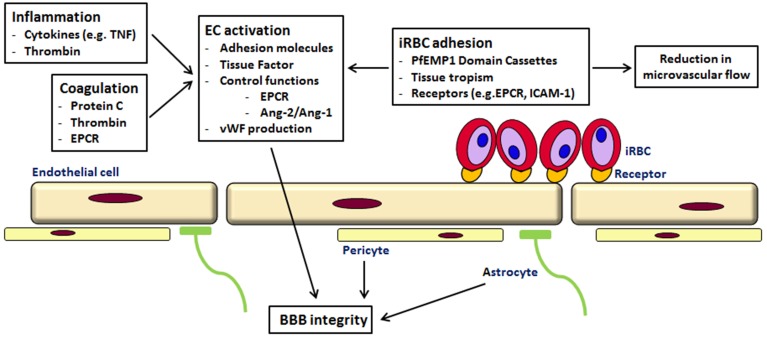

As suggested by others, the pathogenesis of CM is likely to be a multi-factorial process, with sequestration, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in the microvasculature of the brain leading to coma (see Figure 1) (van der Heyde et al., 2006; Milner, 2010; Grau and Craig, 2012; Shikani et al., 2012; Cunnington et al., 2013b). However, the recent findings of the involvement of coagulation and cytoadherence of particular parasite variants to specific receptors have to be taken into account. So perhaps the reason why brain microvascular endothelium is more susceptible to a P. falciparum infection than other tissues is the occurrence of the “correct” combination of parasite variant, endothelial receptors, local inflammation, coagulation and endothelial activation Thus, future work may need to focus not on single attributes associated with disease but more complicated interactions based on both host and pathogen characteristics. This has recently been shown in children with CM; the expression of a parasite PfEMP1 variant (group A) and endothelial activation, as measured by angiopoitein-2 concentration, were independently associated with coma (Abdi et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

Cerebral malaria—a multi-component disease. Cytoadherence of iRBC of the PfEMP1-DC8 and DC13 variants to endothelial receptors (like EPCR and ICAM-1) leads to sequestration and a reduction in microvascular flow. Binding to EPCR prevents activation of protein C, normally an inhibitor of thrombin generation. Increased thrombin affects various signaling pathways leading to loss of endothelial barrier function, increased TNF, Ang2/Ang1 ratio and von Willebrand factor (for a detailed description see Moxon et al., 2013). iRBC in the circulation and the rupture of iRBC elicits an immune response and the production of cytokines, Via various signaling pathways this leads to inflammation, an increased expression of endothelial receptors and therefore shedding of soluble endothelial receptors and ultimately to endothelial damage (see Miller et al., 2013). The leakage into the perivascular space affects astrocytes and pericytes leading to BBB impairment.

Diagnosis and treatment of CM

Biomarkers for CM

The emphasis on just one feature of CM development probably explains why identified biomarkers, to diagnose CM in an early stage or to predict death, have shown only moderate sensitivity and specificity. Up to 2011 there was no single reliable biomarker for CM, but potential markers, including the Ang2/Ang1 ratio, were identified, as reviewed by Lucchi (Lucchi et al., 2011). However, combining multiple host markers of inflammation and endothelial activation can predict mortality accurately in children with SM (Erdman et al., 2011). Histidine-rich protein 2 (HRP2) seems a promising candidate, measuring total parasite biomass, peripheral and sequestered. Its high concentration on admission is prognostic for the risk of death due to SM, including CM (Dondorp et al., 2005; Hendriksen et al., 2012; Fox et al., 2013) and furthermore the concentration is elevated in children with retinopathy compared to children without retinopathy, discriminating between coma caused by CM or other infections. (Seydel et al., 2012; Kariuki et al., 2014). Recently, proteomics has been utilized to screen for potential biomarkers and it may also identify pathways which relate to the pathogenesis of CM (Burte et al., 2012; Gitau et al., 2013; Bachmann et al., 2014).

Therapeutic approaches

Treatment of CM with intravenous artesunate (the WHO recommendation) is not sufficient to prevent all deaths, although it has shown a significant reduction compared to quinine. To further reduce mortality and neurological sequelae in survivors, adjunctive therapies are required. As reviewed by Higgins et al not one immuno-modulatory intervention tested till 2011 had a clear benefit and often adverse events were reported (Higgins et al., 2011). Meanwhile, two other randomized controlled trials have been reported; vitamin A in Ugandan children (Mwanga-Amumpaire et al., 2012) and levamisole in adults with SM in Bangladesh (Maude et al., 2014), but no benefit was recorded in both studies. Clinical trials with erythropoietin and inhaled nitric oxide are apparently ongoing. For L-arginine, the precursor of nitric oxide, a randomized pilot has shown that it was safe, but it did not improve nitric oxide bioavailability (Yeo et al., 2013). Furthermore, therapies that prevent seizures during coma and neurological damage in survivors, such as fosphenytoin, also do not have an effect (Gwer et al., 2013). All these interventions were based on one of the attributes of the pathogenesis of CM and it will be more beneficial to target multiple mechanisms, as outlined above.

Summary

The picture that is emerging for CM is complicated, both in the variability of its presentation between adults and children, and even within children, as well as the mechanisms that cause pathology. Our understanding of the events taking place at the microvascular interface is improving and this greater knowledge will hopefully allow us to design therapeutic interventions that can act to prevent severe symptoms as well as to reverse or reduce mortality and morbidity in established infections.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all our colleagues working on malaria in Blantyre for discussions and communication of unpublished data and the many participants in malaria studies, whose continuing support for malaria research provides the basis for the insights into this disease. We would also like to thank the Wellcome Trust for supporting our research.

References

- Abdi A. I., Fegan G., Muthui M., Kiragu E., Musyoki J. N., Opiyo M., et al. (2014). Plasmodium falciparum antigenic variation: relationships between widespread endothelial activation, parasite PfEMP1 expression and severe malaria. BMC Infect. Dis. 14, 170 10.1186/1471-2334-14-170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adukpo S., Kusi K. A., Ofori M. F., Tetteh J. K., Amoako-Sakyi D., Goka B. Q., et al. (2013). High plasma levels of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 are associated with cerebral malaria. PLoS ONE 8:e84181 10.1371/journal.pone.0084181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aird W. C., Mosnier L. O., Fairhurst R. M. (2014). Plasmodium falciparum picks (on) EPCR. Blood 123, 163–167 10.1182/blood-2013-09-521005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angchaisuksiri P. (2014). Coagulopathy in malaria. Thromb. Res. 133, 5–9 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstey N. M., Weinberg J. B., Hassanali M. Y., Mwaikambo E. D., Manyenga D., Misukonis M. A., et al. (1996). Nitric oxide in Tanzanian children with malaria: inverse relationship between malaria severity and nitric oxide production/nitric oxide synthase type 2 expression. J. Exp. Med. 184, 557–567 10.1084/jem.184.2.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armah H., Dodoo A. K., Wiredu E. K., Stiles J. K., Adjei A. A., Gyasi R. K., et al. (2005). High-level cerebellar expression of cytokines and adhesion molecules in fatal, paediatric, cerebral malaria. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 99, 629–647 10.1179/136485905X51508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armah H. B., Wilson N. O., Sarfo B. Y., Powell M. D., Bond V. C., Anderson W., et al. (2007). Cerebrospinal fluid and serum biomarkers of cerebral malaria mortality in Ghanaian children. Malar. J. 6, 147 10.1186/1475-2875-6-147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avril M., Brazier A. J., Melcher M., Sampath S., Smith J. D. (2013). DC8 and DC13 var genes associated with severe malaria bind avidly to diverse endothelial cells. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003430 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avril M., Tripathi A. K., Brazier A. J., Andisi C., Janes J. H., Soma V. L., et al. (2012). A restricted subset of var genes mediates adherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to brain endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E1782–E1790 10.1073/pnas.1120534109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann J., Burte F., Pramana S., Conte I., Brown B. J., Orimadegun A. E., et al. (2014). Affinity proteomics reveals elevated muscle proteins in plasma of children with cerebral malaria. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004038 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beare N. A., Lewallen S., Taylor T. E., Molyneux M. E. (2011). Redefining cerebral malaria by including malaria retinopathy. Future Microbiol. 6, 349–355 10.2217/fmb.11.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeson J. G., Chan J. A., Fowkes F. J. (2013). PfEMP1 as a target of human immunity and a vaccine candidate against malaria. Expert Rev. Vaccines 12, 105–108 10.1586/erv.12.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendt A. R., Ferguson D. J., Gardner J., Turner G., Rowe A., McCormick C., et al. (1994b). Molecular mechanisms of sequestration in malaria. Parasitology 108(Suppl.), S19–S28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendt A. R., Tumer G. D., Newbold C. I. (1994a). Cerebral malaria: the sequestration hypothesis. Parasitol. Today 10, 412–414 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90238-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmark B., Bergmark R., Beaudrap P. D., Boum Y., Mwanga-Amumpaire J., Carroll R., et al. (2012). Inhaled nitric oxide and cerebral malaria: basis of a strategy for buying time for pharmacotherapy. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 31, e250–e254 10.1097/INF.0b013e318266c113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin G. I., Lavstsen T., Guillonneau F., Doritchamou J., Wang C. W., Jespersen J. S., et al. (2013). Expression of the domain cassette 8 Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 is associated with cerebral malaria in Benin. PLoS ONE 8:e68368 10.1371/journal.pone.0068368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbeck G. L., Molyneux M. E., Kaplan P. W., Seydel K. B., Chimalizeni Y. F., Kawaza K., et al. (2010). Blantyre Malaria Project Epilepsy Study (BMPES) of neurological outcomes in retinopathy-positive paediatric cerebral malaria survivors: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 9, 1173–1181 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70270-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeuf P. S., Loizon S., Awandare G. A., Tetteh J. K., Addae M. M., Adjei G. O., et al. (2012). Insights into deregulated TNF and IL-10 production in malaria: implications for understanding severe malarial anaemia. Malar. J. 11, 253 10.1186/1475-2875-11-253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin M. J., Gladstone M. J., Vokhiwa M., Birbeck G. L., Magen J. G., Page C., et al. (2011). Developmental outcomes in Malawian children with retinopathy-positive cerebral malaria. Trop. Med. Int. Health 16, 263–271 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02704.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H., Turner G., Rogerson S., Tembo M., Mwenechanya J., Molyneux M., et al. (1999). Cytokine expression in the brain in human cerebral malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 180, 1742–1746 10.1086/315078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull P. C., Buckee C. O., Kyes S., Kortok M. M., Thathy V., Guyah B., et al. (2008). Plasmodium falciparum antigenic variation. Mapping mosaic var gene sequences onto a network of shared, highly polymorphic sequence blocks. Mol. Microbiol. 68, 1519–1534 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06248.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burte F., Brown B. J., Orimadegun A. E., Ajetunmobi W. A., Battaglia F., Ely B. K., et al. (2012). Severe childhood malaria syndromes defined by plasma proteome profiles. PLoS ONE 7:e49778 10.1371/journal.pone.0049778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canavese M., Spaccapelo R. (2014). Protective or pathogenic effects of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as potential biomarker in cerebral malaria. Pathog. Glob. Health 108, 67–75 10.1179/2047773214Y.0000000130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J. A., Howell K. B., Reiling L., Ataide R., Mackintosh C. L., Fowkes F. J., et al. (2012). Targets of antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes in malaria immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 3227–3238 10.1172/JCI62182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens A., Adams Y., Ghumra A., Lindergard G., Buchan C. C., Andisi C., et al. (2012). A subset of group A-like var genes encodes the malaria parasite ligands for binding to human brain endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E1772–E1781 10.1073/pnas.1120461109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark I. A., Alleva L. M. (2009). Is human malarial coma caused, or merely deepened, by sequestration? Trends Parasitol. 25, 314–318 10.1016/j.pt.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark I. A., Rockett K. A. (1994a). Sequestration, cytokines, and malaria pathology. Int. J. Parasitol. 24, 165–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark I. A., Rockett K. A. (1994b). The cytokine theory of human cerebral malaria. Parasitol. Today 10, 410–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes V., Taylor T. E., Juhan-Vague I., Mege J. L., Mwenechanya J., Tembo M., et al. (2004). Circulating endothelial microparticles in malawian children with severe falciparum malaria complicated with coma. JAMA 291, 2542–2544 10.1001/jama.291.21.2542-b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy A. L., Lafferty E. I., Lovegrove F. E., Krudsood S., Tangpukdee N., Liles W. C., et al. (2009). Whole blood angiopoietin-1 and -2 levels discriminate cerebral and severe (non-cerebral) malaria from uncomplicated malaria. Malar. J. 8, 295 10.1186/1475-2875-8-295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy A. L., Phiri H., Hawkes M., Glover S., Mallewa M., Seydel K. B., et al. (2010). Endothelium-based biomarkers are associated with cerebral malaria in Malawian children: a retrospective case-control study. PLoS ONE 5:e15291 10.1371/journal.pone.0015291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig A. G., Grau G. E., Janse C., Kazura J. W., Milner D., Barnwell J. W., et al. (2012b). The role of animal models for research on severe malaria. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002401 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig A. G., Khairul M. F., Patil P. R. (2012a). Cytoadherence and severe malaria. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 19, 5–18 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserti-Gazdewich C. M., Dzik W. H., Erdman L., Ssewanyana I., Dhabangi A., Musoke C., et al. (2010). Combined measurement of soluble and cellular ICAM-1 among children with Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Uganda. Malar. J. 9, 233 10.1186/1475-2875-9-233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnington A. J., Riley E. M., Walther M. (2013a). Microvascular dysfunction in severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 207, 369–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnington A. J., Riley E. M., Walther M. (2013b). Stuck in a rut? Reconsidering the role of parasite sequestration in severe malaria syndromes. Trends Parasitol. 29, 585–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza J. B., Hafalla J. C., Riley E. M., Couper K. N. (2010). Cerebral malaria: why experimental murine models are required to understand the pathogenesis of disease. Parasitology 137, 755–772 10.1017/S0031182009991715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondorp A. M., Desakorn V., Pongtavornpinyo W., Sahassananda D., Silamut K., Chotivanich K., et al. (2005). Estimation of the total parasite biomass in acute falciparum malaria from plasma PfHRP2. PLoS Med. 2:e204 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorovini-Zis K., Schmidt K., Huynh H., Fu W., Whitten R. O., Milner D., et al. (2011). The neuropathology of fatal cerebral malaria in malawian children. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 2146–2158 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman L. K., Dhabangi A., Musoke C., Conroy A. L., Hawkes M., Higgins S., et al. (2011). Combinations of host biomarkers predict mortality among Ugandan children with severe malaria: a retrospective case-control study. PLoS ONE 6, e17440 10.1371/journal.pone.0017440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esamai F., Ernerudh J., Janols H., Welin S., Ekerfelt C., Mining S., et al. (2003). Cerebral malaria in children: serum and cerebrospinal fluid TNF-alpha and TGF-beta levels and their relationship to clinical outcome. J. Trop. Pediatr. 49, 216–223 10.1093/tropej/49.4.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser C., Bachmann A., Kuhn D., Schuldt K., Forster B., Thiel M., et al. (2014). Evidence of promiscuous endothelial binding by Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Cell. Microbiol. 16, 701–708 10.1111/cmi.12270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairhurst R. M., Bess C. D., Krause M. A. (2012). Abnormal PfEMP1/knob display on Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes containing hemoglobin variants: fresh insights into malaria pathogenesis and protection. Microbes Infect. 14, 851–862 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez V., Wahlgren M. (2002). Rosetting and autoagglutination in Plasmodium falciparum. Chem. Immunol. 80, 163–187 10.1159/000058844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox L. L., Taylor T. E., Pensulo P., Liomba A., Mpakiza A., Varela A., et al. (2013). Histidine-rich protein 2 plasma levels predict progression to cerebral malaria in Malawian children with Plasmodium falciparum infection. J. Infect. Dis. 208, 500–503 10.1093/infdis/jit176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillrie M. R., Lee K., Gowda D. C., Davis S. P., Monestier M., Cui L., et al. (2012). Plasmodium falciparum histones induce endothelial proinflammatory response and barrier dysfunction. Am. J. Pathol. 180, 1028–1039 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitau E. N., Kokwaro G. O., Karanja H., Newton C. R., Ward S. A. (2013). Plasma and cerebrospinal proteomes from children with cerebral malaria differ from those of children with other encephalopathies. J. Infect. Dis. 208, 1494–1503 10.1093/infdis/jit334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau G. E., Craig A. G. (2012). Cerebral malaria pathogenesis: revisiting parasite and host contributions. Future Microbiol. 7, 291–302 10.2217/fmb.11.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau G. E., Mackenzie C. D., Carr R. A., Redard M., Pizzolato G., Allasia C., et al. (2003). Platelet accumulation in brain microvessels in fatal pediatric cerebral malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 187, 461–466 10.1086/367960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau G. E., Taylor T. E., Molyneux M. E., Wirima J. J., Vassalli P., Hommel M., et al. (1989). Tumor necrosis factor and disease severity in children with falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 320, 1586–1591 10.1056/NEJM198906153202404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravenor M. B., van Hensbroek M. B., Kwiatkowski D. (1998). Estimating sequestered parasite population dynamics in cerebral malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7620–7624 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwer S. A., Idro R. I., Fegan G., Chengo E. M., Mpoya A., Kivaya E., et al. (2013). Fosphenytoin for seizure prevention in childhood coma in Africa: a randomized clinical trial. J. Crit. Care 28, 1086–1092 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen D. S. (2012). Inflammatory responses associated with the induction of cerebral malaria: lessons from experimental murine models. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1003045 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson J., Dondorp A. M., Day N. P., White N. J. (2013). Reply to Cunnington et al. J. Infect. Dis. 207, 370–371 10.1093/infdis/jis680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes M., Elphinstone R. E., Conroy A. L., Kain K. C. (2013). Contrasting pediatric and adult cerebral malaria: the role of the endothelial barrier. Virulence 4, 543–555 10.4161/viru.25949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriksen I. C., Mwanga-Amumpaire J., von Seidlein L., Mtove G., White L. J., Olaosebikan R., et al. (2012). Diagnosing severe falciparum malaria in parasitaemic African children: a prospective evaluation of plasma PfHRP2 measurement. PLoS Med. 9:e1001297 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins S. J., Kain K. C., Liles W. C. (2011). Immunopathogenesis of falciparum malaria: implications for adjunctive therapy in the management of severe and cerebral malaria. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 9, 803–819 10.1586/eri.11.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollestelle M. J., Donkor C., Mantey E. A., Chakravorty S. J., Craig A., Akoto A. O., et al. (2006). von Willebrand factor propeptide in malaria: evidence of acute endothelial cell activation. Br. J. Haematol. 133, 562–569 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06067.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt N. H., Grau G. E. (2003). Cytokines: accelerators and brakes in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria. Trends Immunol. 24, 491–499 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00229-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idro R., Jenkins N. E., Newton C. R. (2005). Pathogenesis, clinical features, and neurological outcome of cerebral malaria. Lancet Neurol. 4, 827–840 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70247-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis L. J., Nie C. Q., Hansen D. S. (2014). The role of chemokines in severe malaria: more than meets the eye. Parasitology 141, 602–613 10.1017/S0031182013001984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain V., Lucchi N. W., Wilson N. O., Blackstock A. J., Nagpal A. C., Joel P. K., et al. (2011). Plasma levels of angiopoietin-1 and -2 predict cerebral malaria outcome in Central India. Malar. J. 10, 383 10.1186/1475-2875-10-383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariuki S. M., Gitau E., Gwer S., Karanja H. K., Chengo E., Kazungu M., et al. (2014). Value of Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 level and malaria retinopathy in distinguishing cerebral malaria from other acute encephalopathies in Kenyan children. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 600–609 10.1093/infdis/jit500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Higgins S., Liles W. C., Kain K. C. (2011). Endothelial activation and dysregulation in malaria: a potential target for novel therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 18, 177–185 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328345a4cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer S. M., Smith J. D. (2006). A family affair: var genes, PfEMP1 binding, and malaria disease. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 374–380 10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski D., Hill A. V., Sambou I., Twumasi P., Castracane J., Manogue K. R., et al. (1990). TNF concentration in fatal cerebral, non-fatal cerebral, and uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Lancet 336, 1201–1204 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92827-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavstsen T., Turner L., Saguti F., Magistrado P., Rask T. S., Jespersen J. S., et al. (2012). Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 domain cassettes 8 and 13 are associated with severe malaria in children. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E1791–E1800 10.1073/pnas.1120455109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liehl P., Mota M. M. (2012). Innate recognition of malarial parasites by mammalian hosts. Int. J. Parasitol. 42, 557–566 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopansri B. K., Anstey N. M., Weinberg J. B., Stoddard G. J., Hobbs M. R., Levesque M. C., et al. (2003). Low plasma arginine concentrations in children with cerebral malaria and decreased nitric oxide production. Lancet 361, 676–678 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12564-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovegrove F. E., Tangpukdee N., Opoka R. O., Lafferty E. I., Rajwans N., Hawkes M., et al. (2009). Serum angiopoietin-1 and -2 levels discriminate cerebral malaria from uncomplicated malaria and predict clinical outcome in African children. PLoS ONE 4:e4912 10.1371/journal.pone.0004912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchi N. W., Jain V., Wilson N. O., Singh N., Udhayakumar V., Stiles J. K. (2011). Potential serological biomarkers of cerebral malaria. Dis. Markers 31, 327–335 10.1155/2011/345706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCormick I. J., Beare N. A., Taylor T. E., Barrera V., White V. A., Hiscott P., et al. (2014). Cerebral malaria in children: using the retina to study the brain. Brain. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1093/brain/awu001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson G. G., Warrell M. J., White N. J., Looareesuwan S., Warrell D. A. (1985). Human cerebral malaria. A quantitative ultrastructural analysis of parasitized erythrocyte sequestration. Am. J. Pathol. 119, 385–401 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneerat Y., Pongponratn E., Viriyavejakul P., Punpoowong B., Looareesuwan S., Udomsangpetch R. (1999). Cytokines associated with pathology in the brain tissue of fatal malaria. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 30, 643–649 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneerat Y., Viriyavejakul P., Punpoowong B., Jones M., Wilairatana P., Pongponratn E., et al. (2000). Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression is increased in the brain in fatal cerebral malaria. Histopathology 37, 269–277 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00989.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning L., Rosanas-Urgell A., Laman M., Edoni H., McLean C., Mueller I., et al. (2012). A histopathologic study of fatal paediatric cerebral malaria caused by mixed Plasmodium falciparum/Plasmodium vivax infections. Malar. J. 11, 107 10.1186/1475-2875-11-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maude R. J., Beare N. A., Abu Sayeed A., Chang C. C., Charunwatthana P., Faiz M. A., et al. (2009). The spectrum of retinopathy in adults with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 103, 665–671 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maude R. J., Silamut K., Plewes K., Charunwatthana P., Ho M., Abul Faiz M., et al. (2014). Randomized controlled trial of levamisole hydrochloride as adjunctive therapy in severe falciparum malaria with high parasitemia. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 120–129 10.1093/infdis/jit410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medana I. M., Turner G. D. (2006). Human cerebral malaria and the blood-brain barrier. Int. J. Parasitol. 36, 555–568 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. H., Ackerman H. C., Su X. Z., Wellems T. E. (2013). Malaria biology and disease pathogenesis: insights for new treatments. Nat. Med. 19, 156–167 10.1038/nm.3073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner D., Jr., Factor R., Whitten R., Carr R. A., Kamiza S., Pinkus G., et al. (2013). Pulmonary pathology in pediatric cerebral malaria. Hum. Pathol. 44, 2719–2726 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner D. A., Jr. (2010). Rethinking cerebral malaria pathology. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23, 456–463 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833c3dbe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux M. E., Taylor T. E., Wirima J. J., Borgstein A. (1989). Clinical features and prognostic indicators in paediatric cerebral malaria: a study of 131 comatose Malawian children. Q. J. Med. 71, 441–459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery J., Milner D. A., Jr., Tse M. T., Njobvu A., Kayira K., Dzamalala C. P., et al. (2006). Genetic analysis of circulating and sequestered populations of Plasmodium falciparum in fatal pediatric malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 194, 115–122 10.1086/504689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxon C. A., Chisala N. V., Wassmer S. C., Taylor T. E., Seydel K. B., Molyneux M. E., et al. (2014). Persistent endothelial activation and inflammation after Plasmodium falciparum Infection in Malawian children. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 610–615 10.1093/infdis/jit419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxon C. A., Wassmer S. C., Milner D. A., Jr., Chisala N. V., Taylor T. E., Seydel K. B., et al. (2013). Loss of endothelial protein C receptors links coagulation and inflammation to parasite sequestration in cerebral malaria in African children. Blood 122, 842–851 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwanga-Amumpaire J., Ndeezi G., Tumwine J. K. (2012). Effect of vitamin A adjunct therapy for cerebral malaria in children admitted to Mulago hospital: a randomized controlled trial. Afr. Health Sci. 12, 90–97 10.4314/ahs.v12i2.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochola L. B., Siddondo B. R., Ocholla H., Nkya S., Kimani E. N., Williams T. N., et al. (2011). Specific receptor usage in Plasmodium falciparum cytoadherence is associated with disease outcome. PLoS ONE 6:e14741 10.1371/journal.pone.0014741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pain A., Ferguson D. J., Kai O., Urban B. C., Lowe B., Marsh K., et al. (2001). Platelet-mediated clumping of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes is a common adhesive phenotype and is associated with severe malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 1805–1810 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak N. D., Dzikowski R. (2009). PfEMP1: an antigen that plays a key role in the pathogenicity and immune evasion of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41, 1463–1466 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik J. K., Das B. S., Mishra S. K., Mohanty S., Satpathy S. K., Mohanty D. (1994). Vascular clogging, mononuclear cell margination, and enhanced vascular permeability in the pathogenesis of human cerebral malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 51, 642–647 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins D. J., Were T., Davenport G. C., Kempaiah P., Hittner J. B., Ong'echa J. M. (2011). Severe malarial anemia: innate immunity and pathogenesis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 7, 1427–1442 10.7150/ijbs.7.1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polimeni M., Prato M. (2014). Host matrix metalloproteinases in cerebral malaria: new kids on the block against blood-brain barrier integrity? Fluids Barriers CNS 11, 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongponratn E., Riganti M., Harinasuta T., Bunnag D. (1985). Electron microscopy of the human brain in cerebral malaria. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 16, 219–227 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongponratn E., Riganti M., Punpoowong B., Aikawa M. (1991). Microvascular sequestration of parasitized erythrocytes in human falciparum malaria: a pathological study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 44, 168–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponsford M. J., Medana I. M., Prapansilp P., Hien T. T., Lee S. J., Dondorp A. M., et al. (2012). Sequestration and microvascular congestion are associated with coma in human cerebral malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 205, 663–671 10.1093/infdis/jir812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portugal S., Pierce S. K., Crompton P. D. (2013). Young lives lost as B cells falter: what we are learning about antibody responses in malaria. J. Immunol. 190, 3039–3046 10.4049/jimmunol.1203067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postels D. G., Birbeck G. L. (2013). Cerebral malaria. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 114, 91–102 10.1016/B978-0-444-53490-3.00006-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prapansilp P., Medana I., Mai N. T., Day N. P., Phu N. H., Yeo T. W., et al. (2013). A clinicopathological correlation of the expression of the angiopoietin-Tie-2 receptor pathway in the brain of adults with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Malar. J. 12, 50 10.1186/1475-2875-12-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rask T. S., Hansen D. A., Theander T. G., Gorm Pedersen A., Lavstsen T. (2010). Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 diversity in seven genomes–divide and conquer. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6:e1000933 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renia L., Howland S. W., Claser C., Charlotte Gruner A., Suwanarusk R., Hui Teo T., et al. (2012). Cerebral malaria: mysteries at the blood-brain barrier. Virulence 3, 193–201 10.4161/viru.19013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riganti M., Pongponratn E., Tegoshi T., Looareesuwan S., Punpoowong B., Aikawa M. (1990). Human cerebral malaria in Thailand: a clinico-pathological correlation. Immunol. Lett. 25, 199–205 10.1016/0165-2478(90)90115-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley E. M., Stewart V. A. (2013). Immune mechanisms in malaria: new insights in vaccine development. Nat. Med. 19, 168–178 10.1038/nm.3083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson S. J., Tembenu R., Dobano C., Plitt S., Taylor T. E., Molyneux M. E. (1999). Cytoadherence characteristics of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes from Malawian children with severe and uncomplicated malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 61, 467–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe J. A., Claessens A., Corrigan R. A., Arman M. (2009). Adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to human cells: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 11, e16 10.1017/S1462399409001082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu U., Sahoo P. K., Kar S. K., Mohapatra B. N., Ranjit M. (2013). Association of TNF level with production of circulating cellular microparticles during clinical manifestation of human cerebral malaria. Hum. Immunol. 74, 713–721 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherf A., Lopez-Rubio J. J., Riviere L. (2008). Antigenic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62, 445–470 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydel K. B., Fox L. L., Glover S. J., Reeves M. J., Pensulo P., Muiruri A., et al. (2012). Plasma concentrations of pHRP2 distinguish between retinopathy-positive and retinopathy-negative cerebral malaria in Malawian children. J. Infect. Dis. 206, 309–318 10.1093/infdis/jis371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydel K. B., Milner D. A., Jr., Kamiza S. B., Molyneux M. E., Taylor T. E. (2006). The distribution and intensity of parasite sequestration in comatose Malawian children. J. Infect. Dis. 194, 208–205 10.1086/505078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikani H. J., Freeman B. D., Lisanti M. P., Weiss L. M., Tanowitz H. B., Desruisseaux M. S. (2012). Cerebral malaria: we have come a long way. Am. J. Pathol. 181, 1484–1492 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence P. J., Langhorne J. (2012). T cell control of malaria pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24, 444–448 10.1016/j.coi.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. M., Cerami C., Fairhurst R. M. (2013). Hemoglobinopathies: slicing the Gordian knot of Plasmodium falciparum malaria pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003327 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor T. E., Fu W. J., Carr R. A., Whitten R. O., Mueller J. S., Fosiko N. G., et al. (2004). Differentiating the pathologies of cerebral malaria by postmortem parasite counts. Nat. Med. 10, 143–145 10.1038/nm986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor W. R., Hanson J., Turner G. D., White N. J., Dondorp A. M. (2012). Respiratory manifestations of malaria. Chest 142, 492–505 10.1378/chest.11-2655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale G., Jennett B. (1974). Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 2, 81–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuma P. E., van Dijk J., Bucala R., Debebe Z., Nekhai S., Kuddo T., et al. (2011). Distinct clinical and immunologic profiles in severe malarial anemia and cerebral malaria in Zambia. J. Infect. Dis. 203, 211–219 10.1093/infdis/jiq041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner G. D., Ly V. C., Nguyen T. H., Tran T. H., Nguyen H. P., Bethell D., et al. (1998). Systemic endothelial activation occurs in both mild and severe malaria. Correlating dermal microvascular endothelial cell phenotype and soluble cell adhesion molecules with disease severity. Am. J. Pathol. 152, 1477–1487 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner G. D., Morrison H., Jones M., Davis T. M., Looareesuwan S., Buley I. D., et al. (1994). An immunohistochemical study of the pathology of fatal malaria. Evidence for widespread endothelial activation and a potential role for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in cerebral sequestration. Am. J. Pathol. 145, 1057–1069 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner L., Lavstsen T., Berger S. S., Wang C. W., Petersen J. E., Avril M., et al. (2013). Severe malaria is associated with parasite binding to endothelial protein C receptor. Nature 498, 502–505 10.1038/nature12216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heyde H. C., Nolan J., Combes V., Gramaglia I., Grau G. E. (2006). A unified hypothesis for the genesis of cerebral malaria: sequestration, inflammation and hemostasis leading to microcirculatory dysfunction. Trends Parasitol. 22, 503–508 10.1016/j.pt.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2013). World Malaria Report 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization [Google Scholar]

- Warimwe G. M., Fegan G., Musyoki J. N., Newton C. R., Opiyo M., Githinji G., et al. (2012). Prognostic indicators of life-threatening malaria are associated with distinct parasite variant antigen profiles. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 129ra45 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassmer S. C., Moxon C. A., Taylor T., Grau G. E., Molyneux M. E., Craig A. G. (2011). Vascular endothelial cells cultured from patients with cerebral or uncomplicated malaria exhibit differential reactivity to TNF. Cell. Microbiol. 13, 198–209 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01528.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White N. J., Pukrittayakamee S., Hien T. T., Faiz M. A., Mokuolu O. A., Dondorp A. M. (2014). Malaria. Lancet 383, 723–735 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60024-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White N. J., Turner G. D., Day N. P., Dondorp A. M. (2013). Lethal malaria: marchiafava and bignami were right. J. Infect. Dis. 208, 192–198 10.1093/infdis/jit116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White V. A., Lewallen S., Beare N., Kayira K., Carr R. A., Taylor T. E. (2001). Correlation of retinal haemorrhages with brain haemorrhages in children dying of cerebral malaria in Malawi. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 95, 618–621 10.1016/S0035-9203(01)90097-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo T. W., Lampah D. A., Gitawati R., Tjitra E., Kenangalem E., McNeil Y. R., et al. (2007). Impaired nitric oxide bioavailability and L-arginine reversible endothelial dysfunction in adults with falciparum malaria. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2693–2704 10.1084/jem.20070819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo T. W., Lampah D. A., Gitawati R., Tjitra E., Kenangalem E., Piera K., et al. (2008). Angiopoietin-2 is associated with decreased endothelial nitric oxide and poor clinical outcome in severe falciparum malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17097–17102 10.1073/pnas.0805782105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo T. W., Lampah D. A., Rooslamiati I., Gitawati R., Tjitra E., Kenangalem E., et al. (2013). A randomized pilot study of L-arginine infusion in severe falciparum malaria: preliminary safety, efficacy and pharmacokinetics. PLoS ONE 8:e69587 10.1371/journal.pone.0069587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo T. W., Lampah D. A., Tjitra E., Piera K., Gitawati R., Kenangalem E., et al. (2010). Greater endothelial activation, Weibel-Palade body release and host inflammatory response to Plasmodium vivax, compared with Plasmodium falciparum: a prospective study in Papua, Indonesia. J. Infect. Dis. 202, 109–112 10.1086/653211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]