Abstract

Background

Mesenchymal stem cells may offer therapeutic potential for asthma due to their immunomodulatory properties and host tolerability, yet prior evidence suggests that bloodborne progenitor cells may participate in airway remodeling. Here, we tested whether mesenchymal stem cells administered as anti‐inflammatory therapy may favor airway remodeling and therefore be detrimental.

Methods

Adipose tissue‐derived mesenchymal stem cells were retrovirally transduced to express green fluorescent protein and intravenously injected into mice with established experimental asthma induced by repeat intranasal house dust mite extract. Controls were house dust mite‐instilled animals receiving intravenous vehicle or phosphate‐buffered saline‐instilled animals receiving mesenchymal stem cells. Data on lung function, airway inflammation, and remodeling were collected at 72 h after injection or after 2 weeks of additional intranasal challenge.

Results

The mesenchymal stem cells homed to the lungs and rapidly downregulated airway inflammation in association with raised T‐helper‐1 lung cytokines, but such effect declined under sustained allergen challenge despite a persistent presence of mesenchymal stem cells. Conversely, airway hyperresponsiveness and contractile tissue underwent a late reduction regardless of continuous pathogenic stimuli and inflammatory rebound. Tracking of green fluorescent protein did not show mesenchymal stem cell integration or differentiation in airway wall tissues.

Conclusions

Therapeutic mesenchymal stem cell infusion in murine experimental asthma is free of unwanted pro‐remodeling effects and ameliorates airway hyper‐responsiveness and contractile tissue remodeling. These outcomes support furthering the development of mesenchymal stem cell‐based asthma therapies, although caution and solid preclinical data building are warranted.

Keywords: airway remodeling; asthma; mesenchymal stem cells; models, animal; muscle, smooth

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) immunoregulatory effects and allogenic tolerance 1 led to investigations into the treatment of severe immune‐mediated diseases 2, which in turn attracted interest on anti‐inflammatory MSCs as a potential asthma treatment. However, the use of MSCs for asthma may face significant limitations. There is evidence that airway remodeling, a relevant feature of asthma pathophysiology, may in part occur through the recruitment and differentiation of circulating progenitor cells, which may differentiate into fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and ultimately airway smooth muscle cells 4. Airway remodeling consists of structural alterations of the airway wall associated with chronic inflammation, including changes such as goblet cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy, subepithelial fibrosis, and increased airway smooth muscle, which underlie the mechanisms of airway hyperresponsiveness, airflow obstruction, and disease severity 13. MSCs administered for therapeutic purposes in asthma may therefore bear a dual potential by reducing inflammation, yet serving as building blocks for airway remodeling given their potential to originate airway structural cells. Here, we employed a mouse model of MSC infusion on asthma to challenge this argument. We genetically modified MSCs to permanently express green fluorescent protein (GFP) so as to track cell fate and administered the MSCs intravenously (i.v.) to animals with established experimental allergic asthma and rhinitis to probe the effects in a scenario reflecting a therapy for ongoing disease. We analyzed airway hyperresponsiveness, inflammation, and remodeling at both an early time point following MSC injection and after a subsequent extension of chronic allergen challenge.

Methods

A detailed description on methods is provided as online supporting information.

Generation and retroviral gene transduction of MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells were harvested from BALB/c mouse adipose tissue, and their phenotype was verified by cytometric marker detection plus verification of multilineage differentiation in adipogenic and osteogenic media. To induce GFP expression for in vivo tracking, AcGFP1 cDNA was subcloned into a murine stem cell virus (MSCV) retrovector and transfected into packaging cells, followed by stable packaging cell line selection. Target MSCs were transduced, and the MSCs, or phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) vehicle, were administered i.v. to recipient mice.

Experimental asthma, pulmonary function, and specimen processing

Syngeneic mice received serial intranasal (i.n.) instillations of standardized house dust mite (HDM) extract (100 μg/nare) or PBS. Lung function measurements were performed by forced oscillation technique on ventilated animals upon challenge with inhaled methacholine (MCh). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and serum were collected. The lungs were fixed under intratracheal standard pressure.

Specimen analyses

Bronchoalveolar lavage total and differential cell counts were performed and cytokines screened with a Luminex 20‐plex panel. Serum IgE was quantified by ELISA. Tissue localization of injected MSCs was detected by GFP. Lung sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E), Masson's trichrome, and periodic acid‐Schiff (PAS); airway contractile tissue (AwCT) was identified by α‐smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA) immunostaining, and quantitative morphology was performed. The craniofacial block was processed to examine the nasal mucosa.

Data analysis

Data distributions are represented as mean and standard error and compared using one‐way analysis of variance followed by Fisher's least significant difference test or Games–Howell test for unequal variances. AwCT and extracellular matrix (ECM) mass are dimensionless. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Numerical data and significant P values are detailed in the Supporting Information File, along with supplemental figures.

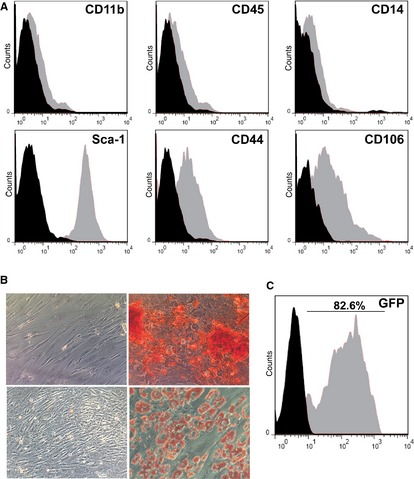

MSCs are efficiently transduced by MSCV‐derived retroviral vectors

Donor adipose tissue yielded MSCs, defined as per a Sca‐1+CD44+CD106+CD11b−CD45−CD14− phenotype (Fig. 1A), and osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation in conditioned media (Fig. 1B). Mesenchymal stem cells targeted with the MSCV/GFP retrovector preserved 99.4% average cell viability and yielded approximately 83% transduced cells expressing GFP (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Phenotyping and retroviral gene transduction of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). (A) Cell surface marker determination by flow cytometry. X‐axes represent fluorescence intensity, and black histograms are from isotype‐matched controls. Following harvesting and culture in MSC selective medium, the adherent cell population showed a Sca‐1+CD44+CD106+CD11b−CD45−CD14− cell surface marker phenotype. (B) The cells produced calcified extracellular matrix upon culture in osteogenic differentiation medium as demonstrated by alizarin‐red staining (upper‐right image) or fat deposits upon culture in adipogenic differentiation medium as shown by oil‐red O staining (lower‐right image). Upper‐left and lower‐left micrographs show the respective stainings on cells cultured in control media. (C) The MSCs were efficiently transduced to express green fluorescent protein employing a murine stem cell virus retroviral vector. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

A single MSC dose leads to a late downshift of airway hyper‐responsiveness

The study design is depicted in Fig. 2A. RL data analysis is detailed in Table S1. On the 72‐h cutoff, the HDM/Veh animals showed airway hyperresponsiveness as demonstrated by a significant increase in RL over baseline and vs the PBS/MSC group (Fig. 2B). The MSCs did not modify airway hyperresponsiveness in the HDM/MSC group, whose RL curve overlaid that of the HDM/Veh group. On the 2‐week cutoff (Fig. 2C), the HDM/MSC animals showed attenuated airway responsiveness as reflected by a downshift of the RL curve, which overlaid the PBS/MSC group, and a significantly decreased RL at 5 mg/ml MCh in comparison with the HDM/Veh group. The data are therefore consistent with a late attenuating effect of MSCs on airway hyperresponsiveness.

Figure 2.

Study design and airway responsiveness to MCh. (A) Experimental asthma was induced in syngeneic mice by intranasal (i.n.) instillation of house dust mite (HDM) extract, three times weekly. Upon 4 weeks on instillations, the mice received 3 × 105 transduced mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) intravenously (i.v.) (HDM/MSC group). Control groups were HDM‐instilled mice receiving i.v. vehicle (HDM/Veh group), or phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS)‐instilled mice receiving MSCs (PBS/MSC group). Pulmonary mechanics and specimen harvesting were performed at 72 h after i.v. MSCs or vehicle (72‐h cutoff), or after 2 weeks of additional i.n. instillations (2‐week cutoff). For those animals studied on the 2‐week cutoff, i.n. installations were thus continued after MSC injection to represent a scenario where subjects undergo continuing exposure to an allergen regularly present in their environment. Small arrows in the time scale and corresponding diamonds indicate i.n. instillations; ‘D’, data collection points. (B, C) Pulmonary resistance (RL) upon MCh challenge was measured at the 72‐h (B) and 2‐week (C) cutoffs. *: P < 0.05 vs PBS/MSC; †: P < 0.05 vs HDM/MSC. The group symbol legend in (B) applies to (B, C).

MSCs migrate to the pulmonary inflammatory infiltrates and alveolar air space and rapidly but transiently downregulate airway inflammation

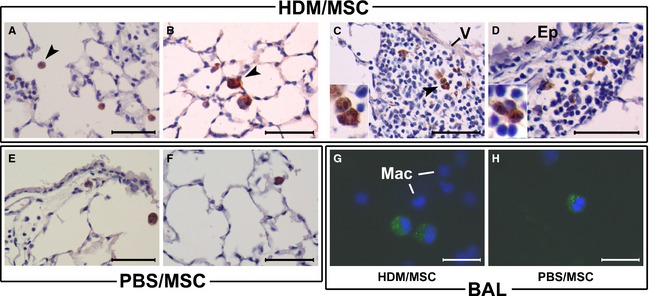

GFP+ MSC localization

GFP+ cells were found in the lungs of recipient mice, both at the 72‐h and at the 2‐week cutoffs (Fig. 3). In the HDM/MSC mice, GFP+ MSCs were found in the perivascular and peribronchial inflammatory infiltrates and in the alveolar air spaces and were retrieved in BAL, where they comprised approximately 5% of the BAL cells in a pooled count. A thorough scan showed no GFP+ MSC localization, nor histopathological evidence of integration or differentiation, into airway wall tissues.

Figure 3.

Location of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in the lung. MSCs were retrovirally transduced to permanently express green fluorescent protein (GFP) and delivered intravenously (i.v.) to mice with established experimental asthma (house dust mite, HDM/MSC group, A–D, G) or disease control mice (phosphate‐buffered saline, PBS/MSC group, E–F, H). Upon 72 h (A) or 2 weeks (B–H) of continued HDM or PBS instillations following MSC infusion, GFP was detected by immunohistochemistry on lung sections (A–F; brown cytoplasmic signal) or from its native fluorescence on cytocentrifuged bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) specimens (G, H). In the latter case, the GFP signal had a distinguishable granular pattern within the cytoplasm, whereas macrophage autofluorescence was below the photographing threshold (DAPI‐stained nuclei of surrounding monocyte/macrophages are shown for reference). GFP+ cells were found in the alveolar air spaces (A–B, E–F) and BAL of both the HDM/MSC and PBS/MSC mice, respectively, and also in the inflammatory infiltrates of HDM/MSC mice, in perivascular (C) and peribronchial (D) location. The GFP+ cells had a round‐shaped cell profile with a large cytoplasm/nucleus ratio and a cell size distinguishably larger than alveolar macrophages, all morphological characteristics consistent with cytological features of MSCs recruited to the lung; (C) and (D) insets show high‐magnification detail. V, vascular wall. Ep, airway epithelium. Mac, macrophages. Arrow heads signal examples of GFP+ MSCs. Scale bars: 100 μm in (A–F); 50 μm in (G, H).

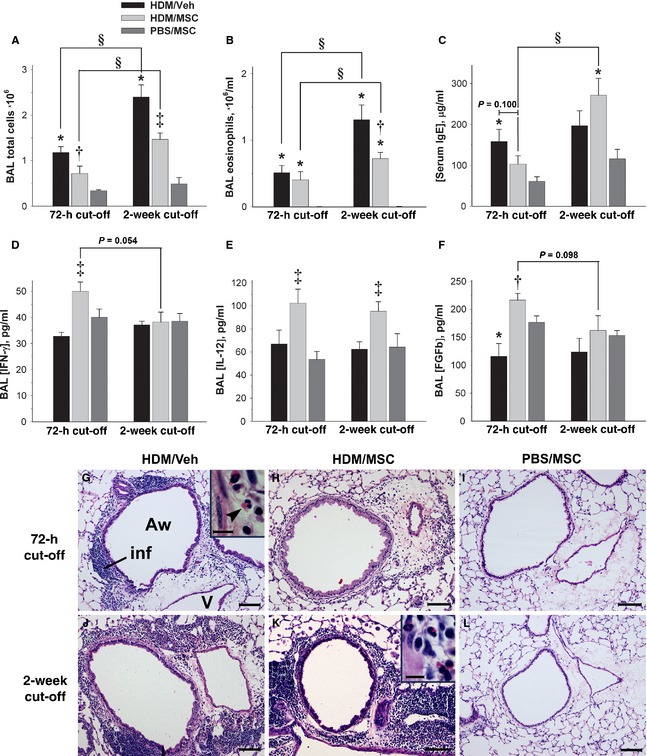

BAL cell counts and serum IgE

The HDM/Veh animals showed at the 72‐h cutoff, vs the PBS/MSC animals, significantly increased BAL cell counts and eosinophils and serum IgE (Fig. 4A–C; full differential leukocyte counts are in Fig. S1; data in Tables S2 and S3). The HDM/MSC animals had a significant reduction in total BAL cells without affecting the eosinophil numbers and a tendency to a reduction in IgE. On the 2‐week cutoff, the HDM/MSC animals showed, compared with the 72‐h cutoff, a significant increment in BAL total cells and absolute eosinophils, and the serum IgE also bounced back with a significant increment.

Figure 4.

Effect of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) on lung inflammation. (A–F) bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and serum analytes, as indicated. The group legend in (A) applies to all plots. *: P < 0.05 vs phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS)/MSC; †: P < 0.05 vs house dust mite (HDM)/Veh; ‡: P < 0.05 vs HDM/Veh and PBS/MSC; §: P < 0.05 for intermodel comparisons as indicated. (G–L) Lung sections (H&E stain), from the experimental groups and cutoff points as indicated. All micrographs show cross‐sectioned airways of approximately equivalent sizes and accompanying vessels. Inflammatory infiltrates, where present, can be observed in the airway wall and perivascular area. The high‐magnification insets show the eosinophilic and mononuclear profile of the inflammatory infiltrates. MSCs attenuated lung inflammation at the 72‐h cutoff as per BAL cell counts (A) and histopathological examination (H). On the 2‐week cutoff, the inflammatory infiltrates seen in the HDM/MSC animals (K) were not distinguishable from those of the HDM/Veh animals (J). Such attenuation and recovery of lung inflammation was associated with a decrease in and rebound of serum IgE (C). The PBS/MSC animals were devoid of lung inflammation (I, L). Aw, airway; inf, inflammatory infiltrate; V, vessel. The arrow head signals an example of eosinophil. Scale bars: 100 μm for large panels; 10 μm for insets.

Lung inflammatory infiltrates

The findings on BAL cellularity and serum IgE had a histopathological correlate on lung tissue sections (Fig. 4G–L). The HDM/Veh animals showed, for both the 72‐h and 2‐week cutoffs, mononuclear and eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrates distributed along the airway wall, perivascular areas, and connective tissue bridging airways and vessels. In the HDM/MSC animals, the intensity of the inflammatory infiltrates was reduced at the 72‐h cutoff in comparison with the HDM/Veh animals, but bounced back on the 2‐week cutoff. In summary, MSCs had an anti‐inflammatory effect at the 72‐h cutoff as reflected by a reduction in BAL leukocyte load, IgE, and tissue inflammatory infiltrates, followed by the restoration of inflammation on the 2‐week cutoff.

Lung goblet cells

Periodic acid‐Schiff staining revealed in the HDM/Veh vs PBS/MSC animals goblet cell enlargement and hyperplasia, which decreased significantly in the HDM/MSC group at the 72‐h cutoff. Concomitantly with the reduction in and rebound of inflammation, a significant goblet cell increment was also reestablished in the HDM/MSC animals on the 2‐week cutoff (Table S4 and Fig. S2).

BAL cytokines

Bronchoalveolar lavage cytokine scan with the Luminex 20‐plex array failed to show a Th2 signature consistent with the demonstration of allergic inflammation by BAL leukocyte counts, serum IgE, and histopathology (Fig. S3). Significant results were obtained for IFN‐γ, IL‐12, and basic fibroblast growth factor (FGFb; Fig. 5D–F and Table S5), which were significantly increased in the HDM/MSC vs HDM/Veh mice at the 72‐h cutoff. The IFN‐γ and FGFb increments faded by the 2‐week cutoff, whereas the increased IL‐12 persisted. The data suggest a transient immune deviation toward a Th1 profile.

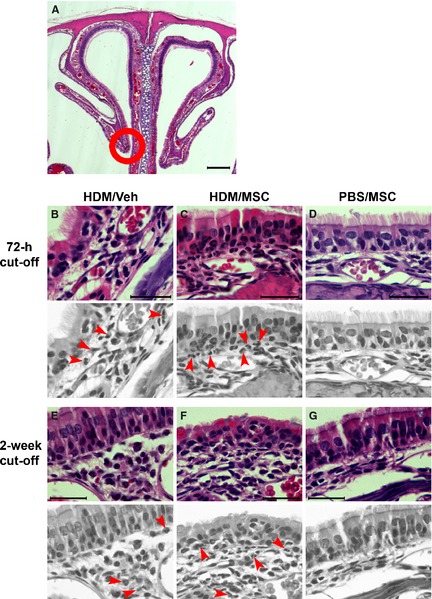

Figure 5.

Histopathology of the nasal mucosa. (A) Low‐magnification view of the nasal cavity showing the septum and nasoturbinates (H&E staining). (B–G) High‐magnification micrographs from the nasoturbinate region encircled in (A). To facilitate interpretation, arrows indicating examples of eosinophils were placed on gray‐scale replicas. The house dust mite (HDM)/Veh and HDM/mesenchymal stem cell animals showed similar inflammatory infiltration for both the 72‐h and 2‐week cutoffs. The eosinophils were mostly located in the subepithelial connective tissue, and some were intraepithelial. Scale bars: 200 μm in (A); 5 μm in (B–G).

Effect on allergic rhinitis

On examination of nose tissue sections (Fig. 5), the HDM/Veh animals showed rhinitis, defined as per eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrates in the nasal mucosa, on both the 72‐h and the 2‐week cutoffs. Such infiltrates were not attenuated in the HDM/MSC group, and no GFP+ cells were found in the nose tissue sections. No discernible structural alterations were observed, and PAS staining did not reveal differences (Fig. S4).

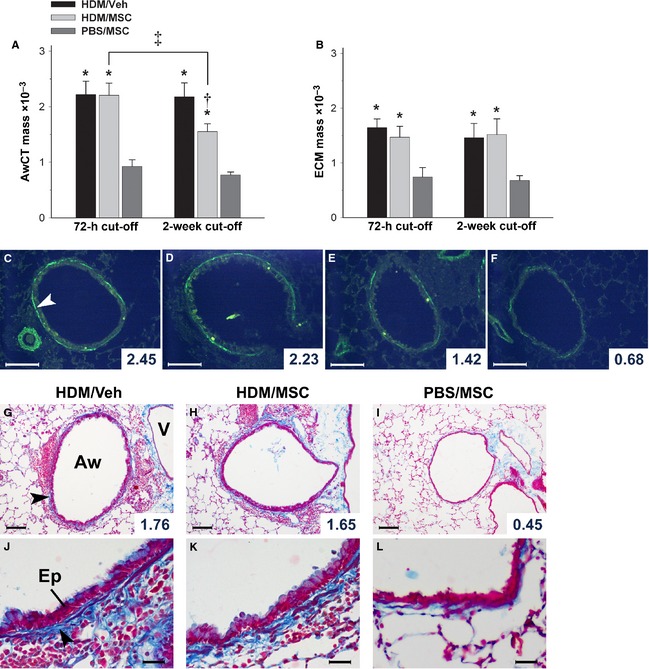

MSCs reduce AwCT mass in dissociation from inflammation and leave ECM unaffected

We analyzed the effects of MSCs on airway remodeling by quantitative morphology on AwCT as per immunofluorescent digital extraction of α‐SMA signal, and Masson's trichrome color extraction as an indicator of ECM deposition (Fig. 6 and Table S6). On the 72‐h cutoff, the HDM/Veh animals showed, in comparison with the PBS/MSC animals, airway remodeling comprising significantly increased AwCT mass and ECM mass. AwCT and ECM remained unchanged in both groups on the 2‐week cutoff. The HDM/MSC animals showed increased AwCT and ECM mass at the 72‐h cutoff, histopathologically and quantitatively indistinguishable from those observed in the HDM/Veh animals. On the 2‐week cutoff, the HDM/MSC animals had a significant reduction in the AwCT mass, whereas the ECM mass remained unchanged. The MSCs led therefore to a late reduction in AwCT mass.

Figure 6.

Effect of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) on airway structure. (A, C–F) AwCT was identified by α‐smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA) immunofluorescent detection. The tissue autofluorescence background allows for histological recognition to identify the α‐SMA signal that corresponds to AwCT. The selected AwCT signal was digitally extracted and normalized by airway size as AwCT mass. The images correspond to a house dust mite (HDM)/Veh animal at 72‐h cutoff (C), HDM/MSC animals at 72‐h (D) and 2‐week (E) cutoffs, and a phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS)/MSC animal at 72‐h cutoff (F). (B, G–L) Masson's trichrome staining was employed to evaluate overall extracellular matrix (ECM). The blue color component corresponding to the airway wall was selected, extracted, and normalized by airway size as ECM mass. Images in (G–L) correspond to the experimental groups as indicated, on the 2‐week cutoff. All micrographs show examples of airways with AwCT or ECM mass values close to the mean of the corresponding group (individual airway values shown). Aw, airway. V, vessel. Ep, airway epithelium. White arrow head in (C) signals AwCT. Black arrow heads in (G, J) signal ECM. *: P < 0.05 vs PBS/MSC; †: P < 0.05 vs HDM/Veh and PBS/MSC; ‡: P < 0.05 for intermodel comparison as indicated. Group legend applies to both A and B. Scale bars: 100 μm in C–I; 25 μm in J–L.

Discussion

We aimed at probing whether MSCs infused as an anti‐inflammatory therapy may favor airway remodeling and thus be detrimental in asthma. Data from clinical studies 11, mathematical modeling 16, and experimental asthma 18 suggest that increased airway smooth muscle is chiefly involved in airway hyperresponsiveness, airflow obstruction, and disease severity. Data on the mechanisms of airway smooth muscle growth in asthma (4, summarized in the Supporting Information File) support a role for recruited precursor cells and suggest the possibility that MSCs infused as an anti‐inflammatory therapy might also bear a potential to favor unwanted remodeling.

Reports on MSCs for asthma therapy, available from murine models only (23, further discussed in the Supporting Information File), show that MSCs attenuate airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness yet leave significant data gaps that should be addressed before any clinical trials can take place. In the clinical setting, that is, established asthma, MSC treatments will face continuing pathogenic stimuli on ongoing disease. Therefore, MSC preclinical development needs further studies that as closely as possible translate to the asthma therapy scenario. This requires to test the effects of MSCs on established disease, assess the outcomes under continuing allergen challenge, and employ models with assessable airway remodeling in a suitable mouse strain under repeated airway challenge for a sufficient period of chronicity. Furthermore, the research on asthma MSC therapy has overlooked the evidence on a role for recruited precursors in airway smooth muscle remodeling. Here, we report on MSCs in HDM‐induced experimental asthma, under the hypothesis of a deleterious contribution to remodeling. We performed chronic i.n. instillations using an actual aeroallergen in the absence of i.p. sensitization and adjuvants to best represent the pathogenesis of human allergic airway disease 30, and we employed the BALB/c mouse to closely encompass the features of human asthma including airway remodeling 22. Mesenchymal stem cells were GFP‐transduced for in vivo tracking and were administered upon established asthma features. Data were generated on two subsequent cutoffs to evaluate both early effects and the outcomes after continuing allergen challenge and active disease, such as in actual human asthma. GFP+ cells, morphologically consistent with infused MSCs in vivo 33, were found in the alveoli and exited in the BAL. In the HDM/MSC mice, GFP+ MSCs were also present in the lung inflammatory infiltrates. The MSCs rapidly attenuated, but did not abrogate, airway inflammation without modifying its eosinophilic profile and concomitantly decreased serum IgE. The proportional reduction in the BAL leukocyte populations is consistent with previous data 27. However, this anti‐inflammatory effect bounced back and airway inflammation was restored after 2 weeks of continued allergen challenge, with a rebound effect on infiltrates, goblet cell hyperplasia, serum IgE, and BAL cells. Such restoration of inflammation occurred despite sustained MSC presence in BAL and tissue sections on the 2‐week cutoff, an observation consistent with data showing that i.v.‐infused MSCs are largely retained in the lungs 23. BAL analysis showed an early increase in IL‐12, IFN‐γ, and FGFb with a subsequent decline of FGFb and IFN‐γ. Th2 cytokines, that is, IL‐5, IL‐4, and IL‐13, were either below quantification level or uninformative regardless of the presence of airway allergic inflammation, mucous metaplasia, and airway remodeling. Technical reasons related to dilution and fluid processing may have blunted the sensitivity to detect effects in the BAL supernatant for part of the cytokine panel analyzed. The effects observed on IL‐12 and IFN‐γ are consistent with a regulation of Th2‐driven inflammation through immune deviation 24 and suggest that the restoration of airway inflammation arose from a decline of the immunoregulatory mechanism. Airway mucous load was reduced by the MSCs as priorly reported 25, but bounced back along with inflammation. Our data therefore suggest that repeated MSC dosing may be necessary for a sustained anti‐inflammatory effect.

Contrary to the decrease in and rebound of inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness was untouched at the 72‐h cutoff but showed a tendency to subsequent attenuation. Although with limited strength, we inferred such attenuation on the basis that: (i) the methacholine response of the HDM/MSC animals, which tightly overlaid that of the HDM/Veh animals at the 72‐h cutoff, subsequently shifted down to equal the PBS/MSC animals on the 2‐week cutoff and (ii) the 2‐week vs 72‐h comparison for HDM/MSC animals was also consistent with a downshift. This was accompanied by a significant, unforeseen effect of the MSCs on airway AwCT remodeling. Whereas ECM remained unmodified, the MSCs led to a late reduction in AwCT mass with no histopathological evidence of MSC integration in the airway wall tissues nor differentiation into lung structural cells. The association with a tendency to declining airway hyperresponsiveness suggests a functional correlate of the decreased AwCT (see the Supporting Information File for further discussion). Noteworthily, AwCT decreased in dissociation from active airway inflammation, which suggests underlying pathways actively inducing a regression of the increased AwCT. A decrease in AwCT in dissociation from restored airway inflammation is to our knowledge the first observation of such nature, and its mechanism is presently unexplained. Because MSCs can differentiate into myofibroblasts and are involved in tissue repair, it is challenging to speculate on the pathways leading to the MSC‐driven decrease in AwCT within a pro‐inflammatory milieu. The fact that the MSCs did not attenuate the rhinitis, nor GFP+ cells were found in the nose tissue sections, suggests that the effects observed in the lungs require close proximity of the MSCs. The modulation of the AwCT mass may be driven through various routes also involving unidentified MSC mediators and indirect pathways, and further research is needed to ascertain its mechanisms (see the Supporting Information File for additional comments and hypothesis building).

In summary, MSCs administered on established experimental asthma rapidly downregulated airway inflammation and mucus production in association with a rise of Th1 cytokines in the lung, but such effects declined under sustained allergen challenge despite a persistent presence of the MSCs. The data suggest that a fading immune deviation mechanism may be, at least in part, responsible for the loss of anti‐inflammatory effect. Whether repeated MSC doses may lead to sustained anti‐inflammatory activity is a standing question of particular relevance for clinical translation that requires pharmacodynamics‐like studies. Conversely, airway AwCT mass underwent a late reduction, associated with a tendency to attenuated airway hyperresponsiveness, regardless of the continued pathogenic stimuli and inflammatory rebound. Furthermore, MSC tracking did not lead to evidence of integration nor differentiation in airway wall tissues. Our data suggest that adipose‐derived MSCs infused as an asthma therapy may be free of unwanted pro‐remodeling effects and may ameliorate AwCT remodeling and airway hyperresponsiveness. These outcomes support furthering research toward a potential use of MSCs in asthma, but caution and solid preclinical data building are warranted.

Author contributions

LMP participated in the experimental work, data compilation, and analysis. IM, OAC, RGI, BLC, IC, and MARM participated in the experimental work and data production. JGC supervised the work at the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid) site and contributed resources and methodological assessment. DRB generated the hypothesis, supervised the work at the INIBIC (A Coruña) and Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona) sites, contributed resources, completed data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria of Spain (FIS Operating Grants PI05/2478, PI05/2217, PI08/1822, PI08/0029, and PI11/01001; Ministry of Science and Innovation and European Regional Development Fund), GlaxoSmithKline (investigator‐driven Collaborative Research Trial), the Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica (SEPAR) and the Fundació Catalana de Pneumologia (FUCAP/Vifor Pharma grant). LMP is the recipient of an Ángeles Alvariño postdoctoral fellowship of Xunta de Galicia, Spain. IMA is supported by Grant PLE2009‐0115 of the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain. OAC and RFI are recipients of FIS postgraduate fellowships FI07/00399 and FI05/00171, respectively. IC is supported by FIS Fund CA10/01315. BLC is supported by Xunta de Galicia Research Unit Consolidation and Structuring Fund INCITE07PXI916208ES. DRB was for part of this work supported by FIS Miguel Servet investigator salary grant CP04/00313.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Extended methods section

Results, data tables

Table S1. RL response to methacholine challenge, cm H2O·s/ml.

Table S2. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cell counts, relative (%) and absolute (cells·106/ml).

Table S3. Serum IgE, μg/ml.

Table S4. Airway PAS+ cells (cells/mm2).

Table S5. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cytokines, pg/ml.

Table S6. AwCT and ECM mass.

Results, supplemental figures

Figure S1. Differential leukocyte counts in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL).

Figure S2. Periodic acid‐Schiff (PAS) staining and quantitative morphology on lung sections.

Figure S3. Mouse Cytokine 20‐Plex Panel.

Figure S4. Periodic acid‐Schiff (PAS) staining of nasal mucosa.

Discussion, supplemental comments

Evidence of progenitor cell contribution to airway smooth muscle growth.

Therapeutic MSCs in murine asthma models.

Airway hyperresponsiveness and AwCT mass.

Mechanism of MSCs‐driven regression of AwCT remodeling.

Mariñas‐Pardo L, Mirones I, Amor‐Carro Ó, Fraga‐Iriso R, Lema‐Costa B, Cubillo I, Rodríguez Milla MÁ, García‐Castro J, Ramos‐Barbón D. Mesenchymal stem cells regulate airway contractile tissue remodeling in murine experimental asthma. Allergy 2014; 69: 730–740

References

- 1.Garcia‐Castro J, Trigueros C, Madrenas J, Perez‐Simon JA, Rodriguez R, Menendez P. Mesenchymal stem cells and their use as cell replacement therapy and disease modelling tool. J Cell Mol Med 2008;12:2552–2565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, Locatelli F, Roelofs H, Lewis I et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid‐resistant, severe, acute graft‐versus‐host disease: a phase II study. Lancet 2008;371:1579–1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trounson A, Thakar RG, Lomax G, Gibbons D. Clinical trials for stem cell therapies. BMC Med 2011;9:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewster CE, Howarth PH, Djukanovic R, Wilson J, Holgate ST, Roche WR. Myofibroblasts and subepithelial fibrosis in bronchial asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1990;3:507–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gizycki MJ, Adelroth E, Rogers AV, O'Byrne PM, Jeffery PK. Myofibroblast involvement in the allergen‐induced late response in mild atopic asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1997;16:664–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt M, Sun G, Stacey MA, Mori L, Mattoli S. Identification of circulating fibrocytes as precursors of bronchial myofibroblasts in asthma. J Immunol 2003;171:380–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nihlberg K, Larsen K, Hultgardh‐Nilsson A, Malmstrom A, Bjermer L, Westergren‐Thorsson G. Tissue fibrocytes in patients with mild asthma: a possible link to thickness of reticular basement membrane? Respir Res 2006;7:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang CH, Huang CD, Lin HC, Lee KY, Lin SM, Liu CY et al. Increased circulating fibrocytes in asthma with chronic airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:583–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolgachev VA, Ullenbruch MR, Lukacs NW, Phan SH. Role of stem cell factor and bone marrow‐derived fibroblasts in airway remodeling. Am J Pathol 2009;174:390–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saunders R, Siddiqui S, Kaur D, Doe C, Sutcliffe A, Hollins F et al. Fibrocyte localization to the airway smooth muscle is a feature of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;123:376–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramos‐Barbon D, Fraga‐Iriso R, Brienza NS, Montero‐Martinez C, Verea‐Hernando H, Olivenstein R et al. T Cells localize with proliferating smooth muscle alpha‐actin+ cell compartments in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:317–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ou‐Yang HF, Han XP, Zhao F, Ti XY, Wu CG. The role of bone marrow‐derived adult stem cells in a transgenic mouse model of allergic asthma. Respiration 2012;83:74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bousquet J, Jeffery PK, Busse WW, Johnson M, Vignola AM. Asthma. From bronchoconstriction to airways inflammation and remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:1720–1745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodruff PG, Dolganov GM, Ferrando RE, Donnelly S, Hays SR, Solberg OD et al. Hyperplasia of smooth muscle in mild to moderate asthma without changes in cell size or gene expression. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169:1001–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox G, Thomson NC, Rubin AS, Niven RM, Corris PA, Siersted HC et al. Asthma control during the year after bronchial thermoplasty. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1327–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiggs BR, Moreno R, Hogg JC, Hilliam C, Pare PD. A model of the mechanics of airway narrowing. J Appl Physiol 1990;69:849–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambert RK, Wiggs BR, Kuwano K, Hogg JC, Pare PD. Functional significance of increased airway smooth muscle in asthma and COPD. J Appl Physiol 1993;74:2771–2781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sapienza S, Du T, Eidelman DH, Wang NS, Martin JG. Structural changes in the airways of sensitized brown Norway rats after antigen challenge. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;144:423–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salmon M, Walsh DA, Huang T‐J, Barnes PJ, Leonard TB, Hay DWP et al. Involvement of cysteinyl leukotrienes in airway smooth muscle cell DNA synthesis after repeated allergen exposure in sensitized Brown Norway rats. Br J Pharmacol 1999;127:1151–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leigh R, Ellis R, Wattie J, Southam DS, de Hoogh M, Gauldie J et al. Dysfunction and remodeling of the mouse airway persist after resolution of acute allergen‐induced airway inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;27:526–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson WRJ, Tang L, Chu S, Tsao S, Chiang GKS, Jones F et al. A role for cysteinyl leukotrienes in airway remodeling in a mouse asthma model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:108–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shinagawa K, Kojima M. Mouse model of airway remodeling: strain differences. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:959–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nemeth K, Keane‐Myers A, Brown JM, Metcalfe DD, Gorham JD, Bundoc VG et al. Bone marrow stromal cells use TGF‐beta to suppress allergic responses in a mouse model of ragweed‐induced asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:5652–5657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park HK, Cho KS, Park HY, Shin DH, Kim YK, Jung JS et al. Adipose‐derived stromal cells inhibit allergic airway inflammation in mice. Stem Cells Dev 2010;19:1811–1818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonfield TL, Koloze M, Lennon DP, Zuchowski B, Yang SE, Caplan AI. Human mesenchymal stem cells suppress chronic airway inflammation in the murine ovalbumin asthma model. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2010;299:L760–L770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodwin M, Sueblinvong V, Eisenhauer P, Ziats NP, Leclair L, Poynter ME et al. Bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stromal cells inhibit Th2‐mediated allergic airways inflammation in mice. Stem Cells 2011;29:1137–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SH, Jang AS, Kwon JH, Park SK, Won JH, Park CS. Mesenchymal stem cell transfer suppresses airway remodeling in a toluene diisocyanate‐induced murine asthma model. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2011;3:205–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Firinci F, Karaman M, Baran Y, Bagriyanik A, Ayyildiz ZA, Kiray M et al. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate the histopathological changes in a murine model of chronic asthma. Int Immunopharmacol 2011;11:1120–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ou‐Yang HF, Huang Y, Hu XB, Wu CG. Suppression of allergic airway inflammation in a mouse model of asthma by exogenous mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2011;236:1461–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson JR, Wiley RE, Fattouh R, Swirski FK, Gajewska BU, Coyle AJ et al. Continuous exposure to house dust mite elicits chronic airway inflammation and structural remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169:378–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCusker C, Chicoine M, Hamid Q, Mazer B. Site‐specific sensitization in a murine model of allergic rhinitis: role of the upper airway in lower airways disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;110:891–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fraga‐Iriso R, Nunez‐Naveira L, Brienza NS, Centeno‐Cortes A, Lopez‐Pelaez E, Verea H et al. Development of a murine model of airway inflammation and remodeling in experimental asthma. Arch Bronconeumol 2009;45:422–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liechty KW, MacKenzie TC, Shaaban AF, Radu A, Moseley AM, Deans R et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells engraft and demonstrate site‐specific differentiation after in utero transplantation in sheep. Nat Med 2000;6:1282–1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anjos‐Afonso F, Siapati EK, Bonnet D. In vivo contribution of murine mesenchymal stem cells into multiple cell‐types under minimal damage conditions. J Cell Sci 2004;117:5655–5664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tolar J, O'Shaughnessy MJ, Panoskaltsis‐Mortari A, McElmurry RT, Bell S, Riddle M et al. Host factors that impact the biodistribution and persistence of multipotent adult progenitor cells. Blood 2006;107:4182–4188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Extended methods section

Results, data tables

Table S1. RL response to methacholine challenge, cm H2O·s/ml.

Table S2. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cell counts, relative (%) and absolute (cells·106/ml).

Table S3. Serum IgE, μg/ml.

Table S4. Airway PAS+ cells (cells/mm2).

Table S5. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cytokines, pg/ml.

Table S6. AwCT and ECM mass.

Results, supplemental figures

Figure S1. Differential leukocyte counts in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL).

Figure S2. Periodic acid‐Schiff (PAS) staining and quantitative morphology on lung sections.

Figure S3. Mouse Cytokine 20‐Plex Panel.

Figure S4. Periodic acid‐Schiff (PAS) staining of nasal mucosa.

Discussion, supplemental comments

Evidence of progenitor cell contribution to airway smooth muscle growth.

Therapeutic MSCs in murine asthma models.

Airway hyperresponsiveness and AwCT mass.

Mechanism of MSCs‐driven regression of AwCT remodeling.