Abstract

♦ Introduction: Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is occasionally used in western sub-Saharan Africa to treat patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The present study is a retrospective review of the initial six years’ experience with PD for ESRD therapy in Senegal, a West African country with a population of over 12 million.

♦ Material and Methods: Single-center retrospective cohort study of patients treated with PD between March 2004 and December 2010. Basic demographic data were collected on all patients. Peritonitis rates, causes of death and reasons for transfer to hemodialysis (HD) were determined in all patients.

♦ Results: Sixty-two patients were included in the study. The median age was 47 ± 13 years with a male/female ratio of 1.21. Nephrosclerosis and diabetic nephropathy were the main causes of ESRD. The mean Charlson score was 3 ± 1 with a range of 2 to 7. Forty five peritonitis episodes were diagnosed in 36 patients (58%) for a peritonitis rate of 1 episode/20 patient-months (0.60 episodes per year). Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were the most commonly identified organisms. Touch contamination has been implicated in 26 cases (57.7%). In 23 episodes (51%), bacterial cultures were negative. Catheter removal was necessary in 12 cases (26.6%) due to mechanical dysfunction, fungal or refractory infection. Sixteen patients died during the study.

♦ Conclusion: Peritoneal dialysis is a suitable therapy which may be widely used for ESRD treatment in western sub-Saharan Africa. A good peritonitis rate can be achieved despite the difficult living conditions of patients. Challenges to the development of PD programs include training health care providers, developing an infrastructure to support the program, and developing a cost structure which permits expansion of the PD program.

Keywords: Peritoneal dialysis, chronic renal failure, Dakar

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is increasingly recognized as a worldwide public health problem. The treatment for ESRD in Africa is often limited and the availability of dialysis is variable. In almost half of African countries, no dialysis patients are reported and no kidney transplants are being done (1).

Hemodialysis (HD) is generally used for ESRD treatment in Africa; peritoneal dialysis (PD) is used sparingly and rarely in West and Central Africa. PD was initiated in Senegal in March 2004 and the present paper reviews the experience with the modality.

Senegal, with an area of 196,712 km2, is located in West Africa. Dakar, the capital, is on a peninsula protruding into the Atlantic Ocean (Figure 1). The population of Senegal is 12,855,153 with an average density of 65.3 inhabitants per km2. Annual population growth is 2.2%. More than 25% of the population lives in the area of Dakar and over 50% lives in rural areas. The population is young, with 58% under 20 years of age. 94% of the population is Muslim, 6% are Christian. Senegal is one of the 50 least developed countries in the world with a gross domestic product (GDP) of 13.09 billion $ and an average life expectancy of 57.5 years. Public expenditures on health are 2.3% of GDP or $12.18 (US) per capita per year (2). The incidence of chronic kidney disease in Senegal has been estimated to be between 300 to 500 new cases per million inhabitants per year (3).The dialysis population number was 230 patients in December 2010; 30 patients were being treated by PD (13%). Six hemodialysis centers are available in the country, with five centers in Dakar and one in Saint Louis (270 km from Dakar). Kidney transplantation is unavailable as an ESRD treatment.

Figure 1 —

Map of Senegal.

The present study is a review of the initial six years of PD therapy in Senegal.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study of patients treated with PD from March 2004 to December 2010 in the nephrology department of the University Hospital A. Le Dantec in Dakar, the only public PD center in the country and the West African area. Patient selection was based on clinical and financial criteria. State employees receive 80% financial support. Some patients are paid for by their families or by private insurance and others paid the entire fee out of pocket. Eligible patients were examined to eliminate contra-indications to PD and their choice was confirmed after information about the different dialysis modalities was provided. Housing circumstances were reviewed using a home visit and a questionnaire prior to acceptance of the patient on PD. Acceptance was restricted to those who had running water, electricity and the availability of their own room to carry out the treatment. The study was approved by the local ethics committee. We included all incident ESRD patients who started PD and completed the initial 15 days of therapy. Surgical implantation of a double cuff Tenckhoff catheter was performed by one of six surgeons, using local anesthesia. For continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD), a Y-set connection system for exchanges was used; Baxter Healthcare (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL, USA) systems were used in the first three years and those of Fresenius Medical Care (Bad Homburg, Germany) since 2007. The Baxter HomeChoice Cycler was used for automated peritoneal dialysis (APD) from the beginning of the program. CAPD patients in general used four exchanges per day and APD patients six cycles per night with a daytime dwell. Patients were trained by the same nurse, usually as outpatients. Standard lactate-based solutions containing 1.36%, 2.27% and 3.86% dextrose were used. Icodextrin and amino acid-based solutions were used in selected cases to help with the management of fluid overload or malnutrition.

For every patient, basic epidemiological, clinical, and outcome data were obtained. The peritonitis rate was determined and examined according to sex, wet/dry season (4 vs 8 months’ duration respectively), cause of renal failure, and PD technique. In Dakar, the dry season runs from October to May and the wet season from June to September. Charlson scores were used to evaluate comorbidities at PD entry, using standardized criteria (4). The data were analyzed with Epi info 6.0 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to evaluate survival rate. Significant p values were <0.05.

Results

Sixty-two (62) ESRD patients were treated with PD. The mean age was 47 ± 13 years, with a male to female ratio of 1.21.The majority (n = 38) came from Dakar and suburbs. The patient who lived in the most distant area was in Tambacounda (600 km from Dakar). Thirty-seven percent of patients (n = 23) were State employees. Half the patients (50%, n = 31) were paid for by their families, 3% (n = 2) by private insurance and 10% (n = 6) paid the entire fee out of pocket. The duration of patient education fell from seven to two days on average with the change of PD technique (from Baxter to Fresenius). The causes of renal failure are summarized in Table 1; nephrosclerosis (n = 25) and diabetic glomerulosclerosis (n = 12) were the most common causes of ESRD. At the initiation of PD treatment, mean urine output was 891 ± 235 mL/day. Body mass index was 21 ± 2 kg/m2. Fifty-four patients (87%) did their exchanges alone and did not need assistance. Mean Charlson score was 3 ± 1 with a range of two to seven. Fifty-two (84%) patients were treated by CAPD and ten (16%) by APD. Four patients were Hepatitis B (HBsAg) positive and one was Hepatitis-C (HCV) antibody positive. There were no HIV-positive patients. Icodextrin was prescribed in 21 patients (33%) due to fluid overload.

TABLE 1.

Initial Nephropathy

Forty-five peritonitis episodes were diagnosed in 36 patients (58%) for a peritonitis rate of 1 episode/20 patient-months (0.60 episodes/year). Twenty-six patients (42%) had no episodes of peritonitis. One diabetic patient had four episodes and three episodes were noted in four patients. During the wet season, 31 episodes of peritonitis were noted (1 episode/18 patient-months) while 14 episodes occurred during the dry season (1 episode/23 patient-months). In 23 episodes (51%), bacterial cultures were negative. Of the 22 episodes with positive cultures, gram-positive cocci were noted in nine cases (Staphylococcus aureus in eight cases and Streptococcus in one case). Pseudomonas aeruginosa was the most common gram-negative organism (7/10 cases) but was not significantly different between wet (n = 4) and dry seasons (n = 3) (Table 2). Touch contamination was implicated in 26 cases (57.7%). Associated exit-site infection and tunnel infection were noted in 9 (20%) and 3 (6.6%) peritonitis episodes, respectively. No predisposing factors were identified in seven cases (15%).

TABLE 2.

Microorganisms Responsible for Peritonitis

Empirical treatment of peritonitis in the initial three years used intraperitoneal administration of third-generation cephalosporin for 14 days and gentamicin for five days. Antibiotics were adjusted based on culture results. After evaluation of local bacterial ecology from the first three years, we changed to oral fluoroquinolone with intraperitoneal cefotaxime for 14 days. In 28 cases (62.2%), peritonitis was eradicated and PD therapy successfully continued. Catheter removal was necessary in 12 cases (26.6%) because of mechanical dysfunction or fungal or refractory bacterial infection. Peritonitis rates were not significantly different between the sexes and between diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Peritonitis was more frequent during the wet season (n = 31) than dry season (n = 14) (p = 0.037) and in CAPD patients (n = 36) compared to APD patients (n = 9) (p < 0.025).

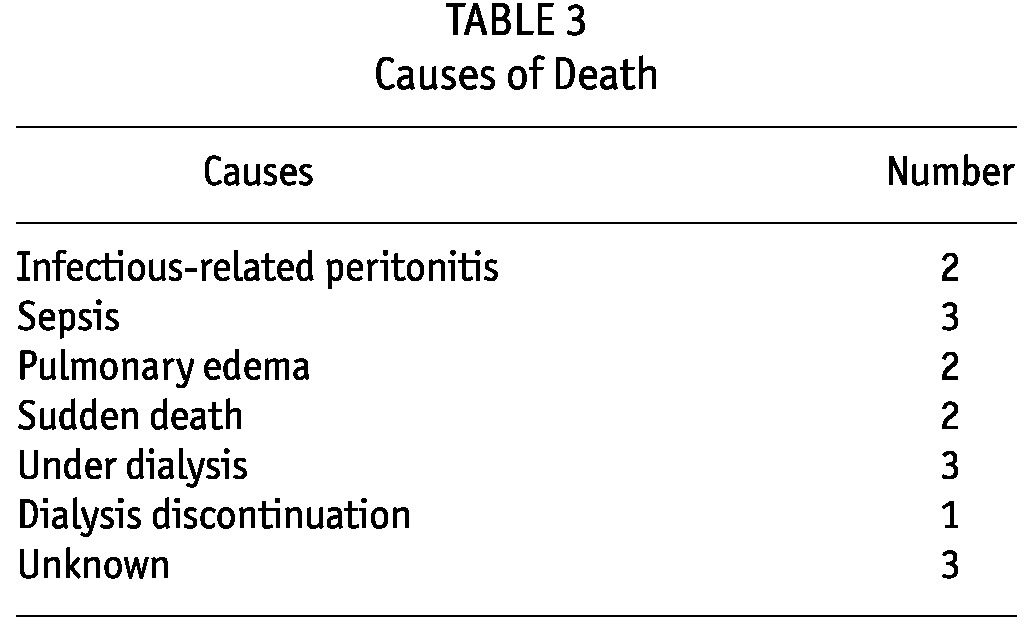

Twelve patients changed to hemodialysis (19.3%). Sixteen patients died (Table 3) from various causes. Death was related to infectious-related peritonitis in two cases and sepsis in three cases. At the end of the study, 34 (54.8%) patients were still maintained on PD (28 patients on CAPD and six on APD). The median time patients had been on PD was 13 months, ranging from 1 to 36 months.

TABLE 3.

Causes of Death

Discussion

Availability of ESRD therapy is limited in Africa. The total dialysis population of Africa was estimated at 69,800 patients in 2007, indicating a rate of 74 patients per million population compared to a global average of 250 per million (1). Of these patients, only 2,050 (2.9%) were treated by PD. The vast majority of ESRD and PD patients in Africa are in South Africa or North Africa. There is very little availability of PD in the western sub-Saharan region. Cost is a major factor in this region. Typically, patients bear the entire cost of treatment due to the absence of healthcare insurance or a social security system.

In Senegal, there are only four HD centers, all in Dakar. In our center, 130 patients are currently being treated for ESRD with dialysis; 22% of these started with PD. The choice of PD was influenced by financial concerns and the lack of HD centers outside of Dakar. At the beginning of our program, the cost of PD was US$1300 per month, similar to the hemodialysis monthly cost in the public sector, and the majority of patients treated had some financial support. In March 2010, the government decided to cover 95% of the PD cost and 80% of hemodialysis. Thus, a patient who begins PD has to pay about US$70 per month.

Clinical features of our population study include a young age (mean of 48 years), low rate of comorbidities, and low prevalence of HCV and HIV infection, reflecting the low prevalence of these infections in Senegal (0.25% and 0.7%, respectively (2,5)). Fifteen percent of the PD patients were HBsAg+, comparable to the HBsAg carrier rate (25%) in the general Senegalese population (5). This high carrier rate of Hepatitis B is a good argument in favor of PD due to the reduced risk of transmission to care providers and other patients. We achieved a good peritonitis rate of 1 episode every 20 patient-months (6). Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas were the most common organisms involved, similar to results reported in the Sudan program (7). As also noted in the Sudan experience, the culture-negative infection rate was higher than the 20% recommended by the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) (6), reflecting problems with basic laboratory support. Twelve catheter removals were required, primarily due to mechanical dysfunction and fungal or refractory bacterial infections. Sixteen patients died (25.8%) from a variety of causes; infections were the leading cause of death.

The present study suggests that PD is a useful dialysis modality in Senegal. Certainly for patients who do not live in large cities with access to HD facilities, PD may be a suitable treatment. There are certain challenges and barriers to the growth of PD. ESRD patients are often referred late in our practice, with no time for patient counseling or adequate planning for dialysis. A large proportion of the population live in rural settings, with limited access to dialysis facilities. Most of our patients face difficulties with transport of their PD supplies. A high occupant-to-bedroom ratio, no electricity, no water supply and informal housing were significantly associated with peritonitis rate (8). A high rate of infection is bad publicity for the modality with patients and practitioners. Lack of facilities for proper culture technique leads to an unacceptably high rate of culture negative peritonitis.

The growth of PD in the region will depend on keeping costs at an acceptable and affordable level. The promotion of domestic manufacture might significantly reduce the costs of dialysis, with substantial financial gain through a larger number of treated patients. Training primary care doctors may help early diagnosis and timely referral of chronic kidney disease patients to the nephrologist. Healthcare providers must be trained in basic PD techniques. The improvement of living standards of our people through access to clean water, electricity and decent housing plays an important role in the development of a PD program.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Fred Finkelstein, who corrected this manuscript.

References

- 1. Abu-Aisha H, Elamin S. Peritoneal dialysis in Africa. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30:23–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Main indicators of Senegal. Agence nationale de la statistique et de la démographie (National agency of statistics and demography). Available at http://www.ansd.sn/ Accessed on 28 September 2011

- 3. Diouf B, Ka EF, Niang A, Diouf ML, Mbengue M, Diop TM. Etiologies of chronic renal insufficiency in an adult internal service in Dakar. Dakar Med 2000; 45(1):62–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic co-morbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis 1987; 5:373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dieye TN. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus in Senegalese blood donors. Dakar Med 2006; 51:47–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, Bernardini J, Figueiredo AE, Gupta A, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections. Recommendations: 2010 update. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30:393–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elhassan EAM, Kaballo B, Fedail H, Abdelraheem MB, Ali T, Medani S, et al. Peritoneal dialysis in the Sudan. Perit Dial Int 2007; 27:503–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lent R, Myers JE, Donald D, Rayner BL. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: an option in the developing world. Perit Dial Int 1994; 14:48–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]