Despite the obvious benefits of peritoneal dialysis (PD) there are a number of associated complications, the most common being exit-site infection and peritonitis (1,2). Permanent and safe access to the peritoneal cavity is fundamental for the success of PD. There are 2 methods of catheter insertion; medical and surgical. Medical insertion is a well-tolerated technique where the catheter is inserted percutaneously under local anesthesia, using the Seldinger technique (3). It can be performed at the bedside, negating the need for operating room time and removing the risks associated with surgery. Surgical insertion is performed under general anesthesia using a paramedian or laparoscopic approach. The choice of insertion is largely dictated by the patient’s past surgical history.

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether the method of catheter placement influences catheter survival and complications.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of outcomes of PD catheters placed percutaneously, using a blind Seldinger technique (PIC) and surgically (SIC). All patients who had commenced PD and had primary placement of PD catheters in 2 centers between 2000 and 2010 were reviewed. Cases were excluded if a catheter insertion was unsuccessful or removed on the day of insertion. Details of the procedures and reasons for removal were collated from the electronic records and case notes.

Blind Seldinger techniques were performed by nephrologists and surgical placement by consultant vascular surgeons in both centers. Surgical placement was done if there was a past history of laparotomy or of severe peritonitis. Curled, double-cuffed PD catheters were used in all cases.

Definitions of Complications

Catheter survival was estimated to the point of catheter removal associated with a complication or elective removal as a result of transfer to another modality. Infective complications associated with PD catheter included peritonitis, exit-site infection or tunnel infection. Mechanical complications comprised catheter malposition or migration leading to poor drainage. Death and patient choice to discontinue PD were included in the general outcomes analyses but not in technique survival.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 13 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used. Catheter survival was analyzed using the Kaplan Meier method. Log Rank p value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Cox Proportional Hazard Model was used for multivariate regression analysis of variables affecting catheter survival. The primary endpoint was catheter removal due to infection or mechanical complications. Categorical variables were assessed using chi square tests and continuous variables using Student t test or Kolmogorov Smirnov Test depending on normality of distribution. Catheter survival was expressed in days, derived from the day of insertion to removal or the point of censor. Infective and mechanical complication rates were expressed as patient months per episode.

Results

Of the 613 patients, 244 were surgical (SIC) and 369 were percutaneous placements (PIC). There was no difference in age; 71.5% of PICs were male as compared with 50% of SICs (p = 0.000). The majority of patients (81.4%) were Caucasian. Predialysis follow-up was greater in the SIC group (p = 0.018). Late presentation (< 3 months of end-stage renal failure) accounted for 107 cases (17.4%) and 73% of these had PIC. Time to insert catheters from late presentation was a median of 0 days for PIC and 1 for SIC. There was no difference between the 2 groups in primary renal disease or diabetes status. Table 1 shows the main results.

TABLE 1.

Main Results

Catheter Removal and Complication Rates

Infections accounted for 28.7% (106/369) of catheter removals in PIC and 38.5% (94/244) in SIC cases (p = 0.014). Mechanical factors led to 16% (59/369) of catheter removals in PIC and 19% (46/244) in SIC cases (p = 0.382). Infective complication rates were 1 in 16.7 patient months in PIC and 1 in 14.7 in SIC. (p = 0.05). Mechanical complication rates were 1 in 4.1 patient months in PIC and 1 in 8.34 in SIC, (p = 0.01). The combined infective and mechanical complications rates were 1 in 12.24 patient months in PIC and 1 in 12.6 in SIC. Early complications (< 28 days) were similar between the groups.

Late Presenting Patients

One hundred and seven patients (17.4%) presented late (LP) with end-stage renal failure; 21% of all PIC and 11.9% of SIC (p < 0.05) were LP. Seventy-eight percent of LP had PIC with an odds ratio of PIC vs SIC of 1.265 (95% confidence interval 1.102 - 1.452, p < 0.05). Of the LP, 23% of PIC patients and 24% of SIC group had infective complications (p = 1.0); mechanical complication occurred in 14% of PIC and 20.7% of SIC (p = 0.39). On survival analysis, risk of catheter failure associated with either complication was similar between LP and early presenters. (Hazard ratio: 0.86, 95% confidence interval 0.62 - 1.20, p = 0.368).

Catheter Survival

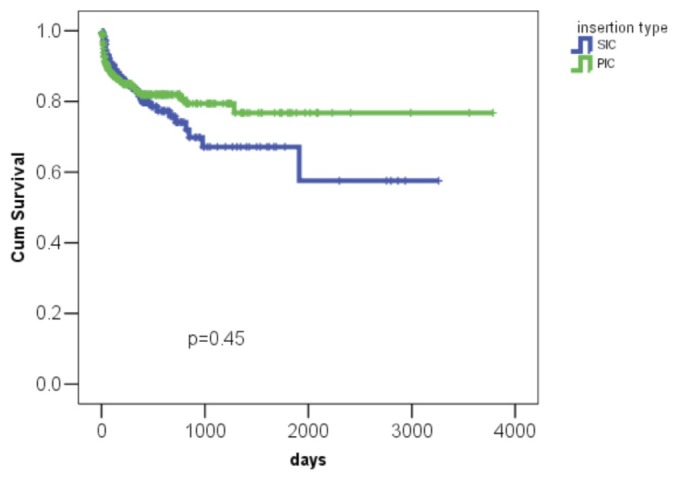

Primary catheter survival between PIC and SIC was similar when mechanical factors were considered alone (p = 0.45) (Figure 1) but not for infective causes (p = 0.018) (Figure 2). Multivariate analysis (Cox Proportional Hazard model) showed only younger age (< 65 years) was independently associated with catheter removal due to infection. Other factors, i.e. treatment center, catheter placement technique, gender, duration of predialysis care, primary renal disease and diabetes status, did not affect catheter survival.

Figure 1 —

Kaplan Meier curves for catheters encountering mechanical complications. SIC = surgical catheter; PIC = percutaneous catheter.

Figure 2 —

Kaplan Meier Survival curves for catheters complicated by infections. SIC = surgical catheter; PIC = percutaneous catheter.

Discussion

This study comparing percutaneously and surgically inserted PD catheters shows percutaneous catheter insertion to be a safe and effective method. Complication rates, early and late, infective and mechanical, were similar in the two groups. There was no difference in catheter survival between the groups. This study also demonstrates that percutaneous PD catheter insertion is safe and effective in patients presenting late for renal replacement therapy.

Most publications in this area are single center experiences (4-6) and all have been supportive of the PIC. In the past PIC was less popular due to concerns of leaks, mechanical complications and the risk of bowel perforation as it does not use direct visualization. To reduce the risk of complications, PIC placement has been performed with the aid of fluoroscopy (7). More recently, laparoscopic (LAP) techniques have been used (8,9). However, both SIC and LAP techniques involve general anesthesia and prolonged hospitalization. A recently published randomized controlled study comparing PIC under radiological guidance, with LAP placement under general anesthetic, showed comparable catheter survival at 1 year but higher mechanical complications in the LAP group (10). Furthermore, the published incidence of perforations following PIC is very low (0 - 1.3%) (11-13). In contrast, there are numerous publications describing visceral injury associated with LAP surgery (14,15).

Complications

There was an increased risk of infective complications in SIC. However, on multivariate analysis, patient’s age (younger cases) was the only factor independently associated with infective complications. This study did not examine the indication for SIC; but in both centers, per protocol, the indication of SIC had been a prior history of laparotomy and/or peritonitis. The overall peritonitis rate was similar to various audit and registry data (16,17). Furthermore, there was no significant difference between the 2 techniques in early complications following PD initiation.

Catheter Survival

Catheter survival between the 2 groups was similar when taking into account mechanical complications. When censored for infective complications, catheter survival was significantly better in the PIC group. However, considering that in a majority of patients surgical placement was performed in those with a previous history of abdominal surgery, one may argue that the overall catheter survival between the groups was comparable. Moreover, there was no difference in catheter survival according to infective or mechanical complications in the first 28 days.

Outcome in Late Presenters

Only 17% of patients presented late in this series, which is in keeping with the UK experience (18). Reassuringly, PD was successful in patients presenting late, with a large majority having PIC. There were no differences in adverse outcomes, either infective or mechanical, and catheter survival was similar in the 2 groups. This reinforces the utility of this technique in safely commencing renal replacement therapy in this group, avoiding the use of venous catheters and hemodialysis.

Limitations and Strengths

The main limitation is that it is a retrospective observational study. In addition, a potential bias is present in selecting patients for PIC or SIC. A randomized controlled study of PIC and SIC in patients, with no prior history of laparotomies, is needed to confirm the findings of this study.

The main strength of this study is that it involves a large cohort of patients with the racial mix reflecting the multicultural society of the UK. We believe the observations should be generalizable. This study also provides contemporary information of outcomes of PD in the UK. Moreover, this study has demonstrated that PIC in late presenting patients can be successfully utilized with comparable catheter survival to SIC.

The PIC technique is simple, easy to learn and reduces surgical burden. It should be adopted more widely with a view to offer safe and effective access for PD which will aid greater utilization of home-based dialysis therapies.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the efforts of the nursing teams and all consultant surgical colleagues involved (T Gardecki, AW Garnham, LD Coen, S Hobbs, S Al Rabban, MX Gannon, A Wilmink, M Scriven) in supporting the care of PD patients in both centers.

References

- 1. Szeto CC, Chow KM, Kwan BC, Law MC, Chung KY, Yu S, et al. Staphylococcus aureus peritonitis complicates peritoneal dialysis: review of 245 consecutive cases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2(2):245–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Szeto CC, Kwan BC, Chow KM, Law MC, Pang WF, Leung CB, et al. Repeat peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis: retrospective review of 181 consecutive cases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6(4):827–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zappacosta AR, Perras ST, Closkey GM. Seldinger technique for Tenckhoff catheter placement. ASAIO Trans 1991; 37:13–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Henderson S, Brown E, Levy J. Safety and efficacy of percutaneous insertion of peritoneal dialysis catheters under sedation and local anaesthetic. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24(11):3499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mellotte GJ, Ho CA, Morgan SH, Bending MR, Eisinger AJ. Peritoneal dialysis catheters: a comparison between percutaneous and conventional surgical placement techniques. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1993; 8:626–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ozener C, Bihorac A, Akoglu E. Technical survival of CAPD catheters: comparison between percutaneous and conventional surgical placement techniques. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001; 16:1893–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abdel-Aal AK, Gaddikeri S, Saddekni S. Technique of peritoneal catheter placement under fluroscopic guidance. Radiol Res Pract 2011; 2011:141707 Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crabtree JH, Kaiser KE, Huen IT, Fishman A. Cost-effectiveness of peritoneal dialysis catheter implantation by laparoscopy versus by open dissection. Adv Perit Dial 2001; 17:88–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crabtree JH, Fishman A. A laparoscopic approach under local anesthesia for peritoneal dialysis access. Perit Dial Int 2000; 20:757–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Voss D, Hawkins S, Poole G, Marshall M. Radiological versus surgical implantation of first catheter for peritoneal dialysis: a randomized non-inferiority trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27(11):4196–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Allon M, Soucie JM, Macon EJ. Complications with permanent peritoneal dialysis catheters: experience with 154 percutaneously placed catheters. Nephron 1988; 48:8–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith SA, Morgan SH, Eastwood JB. Routine percutaneous insertion of permanent peritoneal dialysis catheters on the nephrology ward. Perit Dial Int 1994; 14:284–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Asif A, Byers P, Vieira CF, Merrill D, Gadalean F, Bourgoignie JJ, et al. Peritoneoscopic placement of peritoneal dialysis catheter and bowel perforation: experience of an interventional nephrology program. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 42:1270–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dunne N, Booth MI, Dehn TC. Establishing pneumoperitoneum: Verres or Hasson? The debate continues. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2011; 93:22–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ahmad G, O’Flynn H, Duffy JM, Phillips K, Watson A. Laparoscopic entry techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 2:CD006583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown MC, Simpson K, Kerssens JJ, Mactier RA. Peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis rates and outcomes in a national cohort are not improving in the post-millennium (2000 - 2007). Perit Dial Int 2011; 31(6):639–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cho Y, Badve SV, Hawley CM, McDonald SP, Brown FG, Boudville N, et al. Seasonal variation in peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis: a multi-centre registry study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27(5): 2028–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Udayaraj UP, Haynes R, Winearls CG. Late presentation of patients with end-stage renal disease for renal replacement therapy—is it always avoidable? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26(11):3646–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]