Abstract

Objective

To internally validate the Renal Pelvic Score (RPS) in an expanded cohort of patients undergoing PN.

Materials and Methods

Our prospective institutional RCC database was utilized to identify all patients undergoing PN for localized RCC from 2007–2013. Patients were classified by RPS as having an intra or extraparenchymal renal pelvis. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to examine the relationship between RPS and urine leak.

Results

831 patients (median age 60±11.6 years; 65.1% male) undergoing PN (57.3% robotic) for low (28.9%), intermediate (56.5%), and high complexity (14.5%) localized renal tumors (median size 3.0±2.3cm, median NS 7.0±2.6) were included. 54 (6.5%) patients developed a clinically significant or radiographically identified urine leak. 72/831 (8.7%) of renal pelvises were classified as intraparenchymal. Intrarenal pelvic anatomy was associated with a markedly increased risk of urine leak (43.1% vs. 3.0%; p<0.001), major urine leak requiring intervention (23.6% vs. 1.7%; p<0.001), and minor urine leak (19.4% vs. 1.2%; p<0.001) compared to patients with an extrarenal pelvis. Following multivariable adjustment, RPS (intraparenchymal renal pelvis) (OR 24.8 [CI 11.5–53.4]; p<0.001) was the most predictive of urine leak as was the tumor endophyticity (“E” score of 3 (OR 4.5 [CI 1.3–15.5]; p=0.018)), and intraoperative collecting system entry (OR 6.1 [CI 2.5–14.9]; p<0.001).

Conclusions

Renal pelvic anatomy as measured by the RPS best predicts urine leak following open and robotic partial nephrectomy. While external validation of the RPS is required, pre-operative identification of patients at increased risk for urine leak should be considered in peri-operative management and counseling algorithms.

Keywords: Renal cell carcinoma, renal pelvic score, urine leak, renal pelvis anatomy, partial nephrectomy

Introduction

Nephron sparing surgery (NSS) has become a current standard of care for management of the clinical T1a enhancing renal mass.1 For patients with cT1b lesions, guidelines recommend NSS when technically feasible and renal preservation is warranted.2,3 Relative to radical nephrectomy (RN), NSS is uniquely associated with risks inherent to the technical complexity of the procedure.4,5 As technical prowess grows, patients with anatomically more complex lesions are increasingly treated with partial nephrectomy (PN). The risk of perioperative complications increases with tumor complexity,6,7 with the most common perioperative genitourinary complications being urinary leak and fistulae which occur in upwards of 1 to 20% of patients4,5,8 (1.8%, 10.1%, and 28.1% among patients with low, intermediate, and high complexity tumors, respectively).9 Strategies to reduce the burden of genitourinary complications following PN could reduce perioperative morbidity and improve outcomes.

The Renal Pelvic Score (RPS) is a novel scoring system of renal pelvic anatomy which has previously been associated with urine leak following open PN among a small cohort of patients.10 Our objective was to examine factors associated with urine leak and validate the RPS as an independent predictor of urine leak among an expanded cohort of patients treated with PN.

Methods

Following IRB approval, our prospectively maintained Kidney Cancer Keystone database was queried to identify all patients undergoing PN for clinical stage I–III solid renal tumors from 2007–2013. Clinical variables evaluated included patient (age, gender, race, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] performance status, American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] classification, BMI), tumor (NS, stage, hilar designation, solitary kidney), and operative (procedure type, year of surgery, blood loss, operative time, ischemia time, collecting system entry [CSE]) characteristics. Urine leak was defined as persistent drain output more than 48 hours after PN with analysis consistent with urine or radiographic evidence of urine leak. Urine leak was further sub-classified as major or minor on the basis of need for secondary intervention to achieve leak resolution. Urine leak was examined as both a categorical (presence/absence of leak; need for secondary intervention) and continuous variable (duration of leak). Clinical co-morbidity severity was determined using the weighted Charlson comorbidity index (CCI).11 Tumor anatomic characteristics were assessed using the R.E.N.A.L.-Nephrometry scoring system (NS),12 and patients were stratified into low (NS 4–6), intermediate (NS 7–9), and high (NS 10–12) anatomic complexity groups.12

All surgeries were performed by one of five full-time urologic oncologists, and all masses were approached either through a retroperitoneal flank incision or laparoscopically with robotic assistance. Surgical technique and approach was at the discretion of the primary surgeon. Robotic procedures employed a three-arm technique with port location tailored to the location of the renal tumor and hilum, while open approaches were generally performed extraperitoneally. Intraoperative ultrasound was performed to rule out multifocal disease and delineate resection margins. Hilar control was performed in all cases and tumors were excised sharply with frozen section analysis to determine margin status. Collecting system defects are all noted prospectively and were closed with 4-zero chromic sutures under loupe magnification (open PN) or 3-zero vicryl (robotic PN). Bolsters of oxidized cellulose were placed in the tumor bed before capsular re-approximation. Renorrhaphy was performed using interrupted 3-zero chromic (open PN) or interrupted 3-zero vicryl (robotic PN) sutures. A retroperitoneal drain and urinary catheter were placed in all patients. All patients underwent routine post-operative imaging with either computed tomography or ultrasonography to evaluate renal flow, function and perinephric collections within 14 days post operatively per our institutional pathway. Routine imaging of all patients may identify more leaks than are clinically relevant.

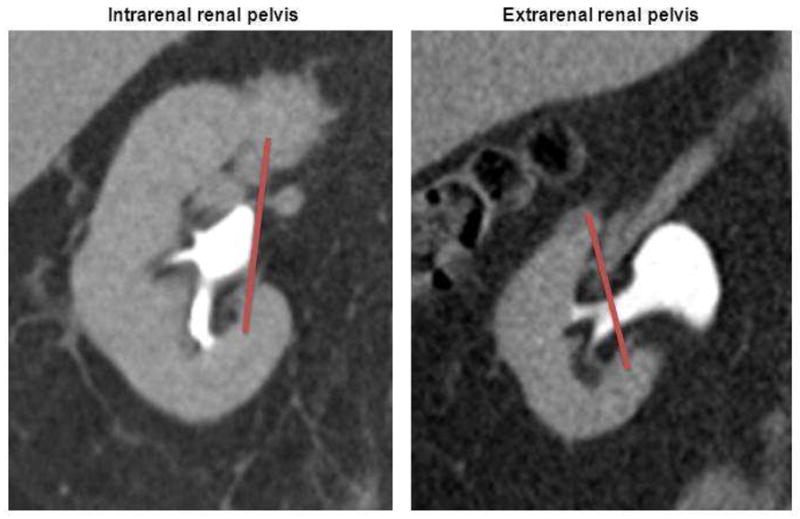

Renal pelvic anatomy was reviewed independently by two staff urologists on preoperative imaging (CT and/or MRI) which was available in all patients, and each pelvis was assigned a RPS as previously described.10 Briefly, a line was drawn connecting the two polar lines on excretory phase images and each pelvis was assigned an RPS based on the percentage of renal pelvis area (by linear dimension) contained inside the volume of the renal parenchyma. Based on the RPS, each renal pelvis was classified as intrarenal (RPS >50%) or extrarenal (RPS <50%) (Fig 1) as previously described,10 and the RPS was used as a categorical variable for statistical analysis.

Figure 1.

As previously described,10 renal pelvic score (RPS) is calculated based on the percentage of the renal pelvis area contained inside the volume of the renal parenchyma. Each renal pelvis can then be subclassified as intrarenal (RPS >50%) or extrarenal (RPS <50%).

Statistical Analysis

Patient, tumor, and operative characteristics were compared between treatment groups using ANOVA and Pearson chi-square analyses. The interobserver agreement between observers determining RPS was calculated using Cohen’s kappa coefficient. The associations between urine leak and intrarenal renal pelvic anatomy were assessed using multinomial logistic regression models using extrarenal renal pelvic anatomy as the reference group. Covariates meeting a P <0.10 level of significance were included for model development, and our final model was adjusted for intrarenal renal pelvis, NS complexity group, total NS, component NS, CCI, ECOG PS, ASA class, pathologic stage, EBL, operative time, warm ischemia time, procedure type, and CSE. All analyses were performed using Stata, version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), all hypothesis tests were 2-sided, and the criterion for statistical significance was P <0.05.

Results

A total of 831 patients (mean/median age 58/60±11.6 years, 65.1% male, 84.6% white, and mean CCI 1.2±1.5) undergoing PN (57.3% robotic) for low (28.9%), intermediate (56.5%), and high complexity (14.5%) localized renal tumors (mean/median tumor size 3.7/3.0±2.3cm, mean/median NS sum 6.1/7.0±2.6) met the final inclusion criteria. 64 (7.7%) patients had an absolute indication for NSS, including 54 (6.5%) patients who had a solitary kidney and 10 (1.2%) patients with bilateral tumors. 92.2%, 6.6%, and 1.2% of patients had clinical stage I, II, and III disease, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics stratified by renal pelvis anatomy.

| Characteristics | Overall Cohort (n=831) | Extrarenal Pelvis (n=759) | Intrarenal Pelvis (n=72) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| PATIENT LEVEL | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age (yrs) (mean ± SD) | 58 ± 12 | 58.4 ± 11.6 | 56.8 ± 11.7 | 0.219 |

|

| ||||

| Gender | 0.577 | |||

| Male | 540 (65.1) | 146 (63.8) | 13 (54.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Race | 0.492 | |||

| White | 704 (84.6) | 641 (84.5) | 63 (87.5) | |

| Non-white | 127 (15.4) | 118 (15.6) | 9 (12.5) | |

|

| ||||

| ECOG PS | 0.0056 | |||

| 0 | 80.7% | 81.3% | 72.2% | |

| ≥ 1 | 6.3% | 6.3% | 8.3% | |

| Unknown | 13.0% | 12.4% | 19.4% | |

|

| ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.6 ± 6.9 | 30.6 ± 6.8 | 30.5 ± 7.1 | 0.947 |

|

| ||||

| CCI | 1.2 ± 1.5 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 1.6 ± 1.7 | 0.0354 |

|

| ||||

| Solitary Kidney | 6.5% | 6.1% | 11.1% | 0.0966 |

|

| ||||

| TUMOR LEVEL | ||||

|

| ||||

| Maximal tumor size (cm) | 3.7 ± 2.3 | 3.7 ± 2.3 | 3.7 ± 2.0 | 0.482 |

|

| ||||

| Nephrometry Score | 6.1 ± 2.6 | 6.1 ± 2.6 | 6.3 ± 2.8 | 0.292 |

|

| ||||

| Tumor “R” NS | 0.0756 | |||

| 1 | 573 (70.6) | 531 (71.7) | 42 (59.2) | |

| 2 | 190 (23.4) | 166 (22.4) | 24 (33.8) | |

| 3 | 49 (6.0) | 44 (5.9) | 5 (7.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Tumor “E” NS | 0.865 | |||

| 1 | 284 (35.0) | 261 (35.2) | 23 (32.4) | |

| 2 | 425 (52.3) | 387 (52.2) | 93 (12.6) | |

| 3 | 103 (12.7) | 38 (53.5) | 10 (14.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Tumor “N” NS | 0.4717 | |||

| 1 | 212 (26.1) | 196 (26.5) | 16 (22.5) | |

| 2 | 117 (14.4) | 109 (14.7) | 8 (11.3) | |

| 3 | 483 (59.5) | 436 (58.8) | 47 (66.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Tumor “A” NS | 0.7937 | |||

| A | 388 (47.8) | 354 (47.8) | 34 (47.9) | |

| P | 339 (41.8) | 311 (42.0) | 28 (39.4) | |

| X | 85 (10.5) | 76 (10.3) | 9 (12.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Tumor “L” NS | 0.514 | |||

| 1 | 255 (31.4) | 237 (32.0) | 18 (25.4) | |

| 2 | 291 (35.8) | 263 (35.5) | 28 (39.4) | |

| 3 | 266 (32.8) | 241 (32.5) | 25 (35.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Tumor “h” NS | ||||

| Yes | 127 (15.3) | 115 (76.2) | 12 (70.6) | 0.612 |

|

| ||||

| NS complexity group | <0.001 | |||

| Low (NS 4–6) | 235 (28.9) | 220 (30.0) | 15 (21.1) | |

| Intermediate (NS 7–9) | 459 (56.5) | 415 (56.0) | 44 (62.0) | |

| High (NS 10–12) | 118 (14.5) | 106 (14.3) | 12 (16.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Pathologic stage | 0.0020 | |||

| T0 | 75 (9.1) | 70 (9.3) | 5 (6.9) | |

| T1 | 668 (80.9) | 612 (81.2) | 56 (77.8) | |

| T2 | 47 (5.7) | 44 (5.8) | 3 (4.2) | |

| T3 | 35 (4.2) | 28 (3.7) | 7 (9.7) | |

|

| ||||

| OPERATIVE LEVEL | ||||

|

| ||||

| Procedure type | 0.0399 | |||

| Robotic | 476 (57.3) | 443 (58.4) | 33 (45.8) | |

| Open | 355 (42.7) | 316 (41.6) | 39 (54.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Urine leak | 54 (6.5) | 23 (3.0) | 31 (43.1) | <0.001 |

| Major | 30 (3.6) | 13 (1.7) | 17 (23.6) | |

| Minor | 24 (2.9) | 10 (1.3) | 14 (19.4) | |

|

| ||||

| Collecting system entry | 265 (32.0) | 227 (30.0) | 38 (52.8) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Operative time (min) | 186 ± 62 | 184 ± 61 | 205 ± 77 | 0.0403 |

|

| ||||

| EBL (mL) | 197 ± 269 | 193 ± 270 | 236 ± 260 | 0.1208 |

|

| ||||

| Hospital stay (days) | 4.0 ± 2.9 | 3.9 ± 2.8 | 4.7 ± 3.4 | 0.103 |

|

| ||||

| Duration of leak (days; median) | 63 ± 53 | 56 ± 32 | 65 ± 61 | 0.0984 |

|

| ||||

| Duration ischemia time (min) | 32 ± 116 | 32 ± 121 | 31 ± 19 | 0.0423 |

54 (6.5%) patients developed a clinically identifiable urine leak (median leak duration 63 ± 53 days, range 8–230 days) with a median follow-up of 25.5 ± 51.9 months. 30/54 (55.6%) patients had a major urine leak requiring secondary intervention for leak resolution (22/54 (40.7%) stent, 4/54 (7.4%) nephrostomy tube, 8/54 (14.8%) percutaneous abdominal drain, 5/54 (9.3%) nephrectomy, reconstruction, or angioembolization). In comparing patients with and without urine leak, significant differences in the rate of CSE (79.6 vs. 20.4%; p<0.001), hospital length of stay, EBL, warm ischemia time, and procedure type were observed, while no differences were seen in age, gender, race, BMI, tumor laterality, CCI, largest tumor diameter, NS, operative time, ASA class, and ECOG PS (Table 2). 72 (8.7%) and 759 (91.3%) patients were classified with an intrarenal and extrarenal renal pelvis, respectively. The interobserver agreement (kappa coefficient) was 0.7 (95 CI [0.57–0.77]) for the determination of RPS. 43.1% of patients with an intrarenal pelvis were noted to have a urine leak compared to only 3.0% of patients with an extrarenal pelvis (p<0.001). 23.6% of patients with an intrarenal RPS had a major urine leak compared to 1.7% of patients with an extrarenal RPS (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics and management of urine leak.

| Urine Leak | No Urine Leak | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | 59.4 ± 12.1 | 58.2 ± 11.6 | 0.419 |

|

| |||

| Gender | 0.397 | ||

| Male | 70.4% | 64.7% | |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | 87.0% | 84.6% | 0.624 |

|

| |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.0 ± 7.0 | 30.7 ± 6.8 | 0.310 |

|

| |||

| CCI | 1.7 ± 1.8 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 0.0284 |

|

| |||

| Procedure Type | <0.001 | ||

| Robotic | 12 (22.2) | 464 (59.7) | |

| Open | 42 (77.8) | 313 (40.3) | |

|

| |||

| ECOG PS | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 59.3% | 82.2% | |

| ≥1 | 5.6% | 5.8% | |

| Unknown | 35.2% | 11.2% | |

|

| |||

| Largest Tumor Diameter | 4.1 ± 2.4 | 3.7 ± 2.3 | 0.0985 |

|

| |||

| Nephrometry Score | 5.8 ± 3.4 | 6.2 ± 2.5 | 0.5807 |

|

| |||

| NS Complexity Group | |||

| Low | 3 (5.7) | 232 (30.6) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate | 34 (64.2) | 425 (56.0) | 0.2341 |

| High | 16 (30.2) | 102(13.4) | <0.001 |

| Operative time | 201 ± 76 | 187 ± 61 | 0.1896 |

|

| |||

| Pathologic Stage | <0.001 | ||

| T0 | 2 (3.7) | 73 (9.5) | |

| T1 | 39 (72.2) | 629 (81.5) | |

| T2 | 7 (13.0) | 40 (5.2) | |

| T3 | 5 (9.3) | 30 (3.9) | |

|

| |||

| Solitary Kidney | 6 (11.1) | 48 (6.2) | 0.1550 |

|

| |||

| RPS (Intrarenal pelvis) | <0.001 | ||

| Intrarenal pelvis | 57.4% | 5.3% | |

| Extrarenal pelvis | 42.6% | 94.7% | |

|

| |||

| Collecting system entry | 79.6% | 28.7% | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| EBL (mL) | 322 ± 321 | 188 ± 263 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Duration ischemia time (min) | 32 ± 474 | 26 ± 40 | 0.0115 |

|

| |||

| Required treatment | |||

| Stent | 30 (55.6) | - | - |

| Nephrostomy tube | 22 (56.4) | - | - |

| Perc abd drain | 4 (10.3) | - | - |

| Nx or reconstruction | 8 (20.5) | - | - |

| * 9 patients required multiple interventions | 5 (12.8) | ||

Comparing patients by intra-and extra-renal pelvices, significant differences in procedure type (54.2% vs. 41.6% open, p=0.040), CSE (52.8% vs. 30.0%, p<0.001), operative time (205 ± 77 vs. 186 ± 61 minutes; p=0.041), warm ischemia time (31 ± 19 vs. 27 ± 120 minutes; p=0.042), ASA class, ECOG PS, and tumor stage were observed, while no differences were observed between the remaining variables (Table 2). Intrarenal pelvic anatomy was associated with a markedly increased risk of urine leak (43.1% vs. 3.0%; p<0.001), major urine leak (23.6% vs. 1.7%; p<0.001), and minor urine leak (19.4% vs. 1.2%; p<0.001), but not prolonged duration of urine leak (65 ± 8 vs. 56 ± 9 days; p=0.098) compared to patients with an extrarenal pelvis (Table 3). After controlling for NS, procedure type, CSE, ECOG PS, pathologic stage, ASA status, EBL, operative time, and ischemia time, intraparenchymal RPS (OR 24.8 [CI 11.5–53.4]; p<0.001), “E” score of 3 (OR 4.5 [CI 1.3–15.5]; p=0.018), and CSE (OR 6.1 [CI 2.5–14.9]; p<0.001) were associated with a significantly increased risk of urine leak.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis demonstrating associations between patient characteristics and urine leak.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrarenal pelvis | 24.8 | 13.2–169.4 | <0.001 |

| “E”xophytic/Endophytic score | 4.5 | 1.3–15.5 | 0.0182 |

| 3 (VS. 1) | |||

| Collecting system entry | 6.1 | 2.5–14.9 | <0.001 |

Multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for demographic characteristics, RPS, NS complexity group, total NS, component NS, CCI, ECOG PS, ASA class, pathologic stage, EBL, OR time, ischemia time, procedure type, and CSE. *Only significant associations are listed.

Discussion

Given concerns that significant loss of renal parenchyma may predispose patients to increased cardiovascular risk and shortened overall survival,13,14 the utilization of NSS has increased,15 and PN is now considered the standard of care for managing stage T1a RCC and an option for T1b tumors.1 While NSS remains underutilized,16 a recent analysis revealed that PN was performed in 42.9% and 14.2% of T1a and T1b tumors, respectively.15 With increasing utilization of NSS, the burden of risks uniquely associated with PN, specifically urine leak, may increase.6,9,17 In a previous proof of concept analysis, we identified and quantified intrarenal pelvic anatomy as a unique and quantifiable anatomic variant independently associated with urine leak.10 Herein we rigorously validate the ability of the RPS to predict urine leak and major urine leak among a large contemporary cohort of patients treated with open and robotic PN.

Following adjustment, patients with intrarenal pelvic anatomy had a 25- and 13-fold increased risk of urine leak and major urine leak, respectively. To date, no other preoperative characteristics except tumor complexity as measured by nephrometry9 have been identified that can reliably predict the risk of or the efficiency of intervention to correct a urinary leak.10 The ability to accurately identify patients at the highest risk for urinary leak has the potential to impact management algorithms, patient counseling, the need for intervention as well as associated costs and clinical outcomes. While clinician’s are already faced with numerous time restraints and preoperative nomograms, the utility of the RPS lies within its ease and rapidity of calculation during review of cross sectional imaging. Identification of the novel intrarenal renal pelvis anatomic variant has altered practice at our institution. In patients at highest risk of urine leak, placement of an open-ended temporary stent at the time of surgery and use of retrograde dye injection to facilitate identification of CSE’s is more commonly performed to assess intraoperative closure of CSE.

Genitourinary complications are the most frequent morbidity associated with PN (25.1%),9 and are largely due to the procedure-specific risk of urine leak.4,7,18 Rates of urinary leak range from 0.5–21%, and while contemporary rates following robotic (1.6%)19 and open (2.3%)20 PN are quite low, the risk of urinary leak increases with increasing anatomic tumor complexity,9 with rates as high as 9.8%–18.5%7,21 reported. Given the expanded indications1 for and utilization15 of NSS for larger and more complex tumors, urinary leak remains a challenging complication of NSS and highlights a targeted area for improving outcomes4,7,8,10,18,20 as well as potentially understanding costs and modeling bundled payments around NSS. Our original description of the RPS only considered open PN,10 while the current study represents an important extension to include patients treated in a minimally invasive fashion. While urine leak occurred more frequently following open (11.8%) versus robotic (2.5%) PN, this likely reflects selection of patients with more complex tumors for open intervention. However, following adjustment, the risk of urine leak was independent of procedure type, and the RPS remained the strongest overall predictor of leak. While further studies are needed to determine if incorporation of the RPS into management algorithms can improve the morbidity associated with PN, preoperative consideration of renal pelvic anatomy has the potential to impact patient counseling regarding drain management and expectations, as well as intraoperative reconstruction techniques.

Diligent attention to precise surgical technique is an important consideration in both open and robotic PN. Due to tumor anatomy and/or location, CSE may occasionally be unavoidable and in some cases may go unrecognized. Not surprisingly, CSE was associated with increased risk of major and minor urine leak. In all cases, CSE’s are identified and repaired following tumor excision, but despite adequate repair, the mechanically altered collecting system may predispose to urine leak.7 Distension of the renal pelvis results in non-homogeneous wall movement, and rigid wall areas (e.g., following collecting system repair) further affect regional strain distribution.10 The absence of CSE in some patients with urine leak highlights the multifactorial nature of urine leak, but incomplete CSE repair, unidentified CSE, and renal calyx exclusion can all portend urine leak; these variables, however, are difficult to capture completely at the time of surgery. Others have previously demonstrated an association between CSE and urine leak,7,22 however contrary results may be attributable to incomplete capture of collecting system repair among retrospective studies or studies with limited statistical power due to relatively low rates of urine leak.23,24 The intrarenal pelvis is commonly smaller and associated with longer, thinner infundibula, and a relative decrease in the functional radius of the renal pelvis could result in increased intrapelvic pressure and portend urinary leak following PN.10 In addition, pressure in the collecting system may be heterogeneously distributed with higher pressures present at the renal pole.25 No studies to date have characterized the effect of CSE location, magnitude, or quantity on the risk of urine leak, and classification of CSE as a dichotomous variable is unlikely to fully capture its effect on the complex and dynamic function of the renal pelvis, which may explain the discrepant results observed among different series.

Tumor anatomic attributes affect PN procedural complexity,9,26 and increasing anatomic complexity is associated with increased risk of urine leak.6,9,21,27 With each unit increase in total NS, the risk of postoperative urine leak increases by 35%.6 While overall NS was not associated with urine leak, we observed a greater than four-fold increased risk of urine leak associated with completely endophytic tumor location (“E” score of 3). Among PN cohorts including lesions of higher anatomic complexity, the risk of urine leak is higher, and approaches 20% for patients with stage T2 or greater disease.28 With PN increasingly performed for more complicated and centrally located masses,17 the incidence of urine leak would be expected to increase for larger and more endophytic lesions.7 Among NS elements, the endophytic component appears to have the strongest independent association with urine leak, corroborating the findings of Bruner and colleagues.6

Our analyses are limited by the selection bias inherent to all retrospective cohort studies. Further, as previously described,10 our description of renal pelvic anatomy likely oversimplifies a dynamic functional component of the kidney. While we utilize a strict and conservative definition of urine leak which may not be universally used by all institutions, it is the practice of our group to look intensely for leaks with post-operative imaging. Lack of standardized reporting methods has resulted in an existing body of complications literature that is difficult to interpret,9 and the rigid definition used was chosen in an attempt to capture all clinical leaks, and is consistent with the definition used by prior series.7–10,21 Further, while data regarding the complexity of collecting system repair is not collected (aside from the number of CSE’s), the nephrometry score, which was controlled for in the multivariable model, reflects the complexity of tumor dissection. While our findings require external validation, the current study provides useful clinical insight, identifies easily applicable preoperative risk-stratification parameters, and validates the ability of the RPS to predict urine leak following open and robotic PN. As assessed by preoperative imaging, patients with intrarenal pelvic anatomy as measured by RPS and endophytic tumors (“E” score of 3) should be considered high-risk for perioperative urine leak. Among this “high-risk” cohort, we recommend routine consideration of preoperative open ureteral catheter placement for intraoperative testing. Given the significant effect of CSE on the risk of urine leak, retrograde dye injection may aid in the intraoperative prevention, identification, and repair of CSE. Increasing utilization of PN for more complex tumors will likely increase the burden of perioperative complications, which makes incorporation of RPS into clinical practice all the more timely and useful.

Conclusions

Herein we identify a single anatomic feature, the renal pelvic score, that most reliably predicts the occurrence of a urinary leak following open or MIS NSS and the efficiency of interventions to correct the leak. Elevated pressures within a small intraparenchymal renal pelvis may explain the increased risk. While external validation of the RPS is required, pre-operative identification of patients at increased risk for urine leak should be considered in pre-operative counseling and peri-operative management algorithms.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Debra Kister and Michelle Collins for their expertise and support of the Fox Chase Kidney Cancer Database.

Funding/Support: Supported in part by grant number P30 CA006927 from the National Cancer Institute. Additional funds were provided by Fox Chase Cancer Center via institutional support of the Kidney Cancer Keystone Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Campbell SC, Novick AC, Belldegrun A, et al. Guideline for management of the clinical T1 renal mass. The Journal of urology. 2009;182:1271–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long CJ, Canter DJ, Kutikov A, et al. Partial nephrectomy for renal masses >/= 7 cm: technical, oncological and functional outcomes. BJU international. 2012;109:1450–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weight CJ, Larson BT, Gao T, et al. Elective partial nephrectomy in patients with clinical T1b renal tumors is associated with improved overall survival. Urology. 2010;76:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Poppel H, Da Pozzo L, Albrecht W, et al. A prospective randomized EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the complications of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for low-stage renal cell carcinoma. European urology. 2007;51:1606–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson AJ, Hakimi AA, Snyder ME, et al. Complications of radical and partial nephrectomy in a large contemporary cohort. The Journal of urology. 2004;171:130–134. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000101281.04634.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruner B, Breau RH, Lohse CM, et al. Renal nephrometry score is associated with urine leak after partial nephrectomy. BJU international. 2011;108:67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meeks JJ, Zhao LC, Navai N, et al. Risk factors and management of urine leaks after partial nephrectomy. J Urol. 2008;180:2375–2378. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uzzo RG, Novick AC. Nephron sparing surgery for renal tumors: indications, techniques and outcomes. The Journal of urology. 2001;166:6–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simhan J, Smaldone MC, Tsai KJ, et al. Objective measures of renal mass anatomic complexity predict rates of major complications following partial nephrectomy. European urology. 2011;60:724–730. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomaszewski JJ, Cung B, Smaldone MC, et al. Renal Pelvic Anatomy Is Associated with Incidence, Grade, and Need for Intervention for Urine Leak Following Partial Nephrectomy. European urology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kutikov A, Uzzo RG. The R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score: a comprehensive standardized system for quantitating renal tumor size, location and depth. J Urol. 2009;182:844–853. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;351:1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang WC, Levey AS, Serio AM, et al. Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: a retrospective cohort study. The lancet oncology. 2006;7:735–740. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70803-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang G, Villalta JD, Meng MV, et al. Evolving practice patterns for the management of small renal masses in the USA. BJU international. 2012;110:1156–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.10969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dulabon LM, Lowrance WT, Russo P, et al. Trends in renal tumor surgery delivery within the United States. Cancer. 2010;116:2316–2321. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simmons MN, Gill IS. Decreased complications of contemporary laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: use of a standardized reporting system. The Journal of urology. 2007;177:2067–2073. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.129. discussion 2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wheat JC, Roberts WW, Hollenbeck BK, et al. Complications of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. Urologic oncology. 2013;31:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spana G, Haber GP, Dulabon LM, et al. Complications after robotic partial nephrectomy at centers of excellence: multi-institutional analysis of 450 cases. J Urol. 2011;186:417–421. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill IS, Kavoussi LR, Lane BR, et al. Comparison of 1,800 laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomies for single renal tumors. J Urol. 2007;178:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroup SP, Palazzi K, Kopp RP, et al. RENAL nephrometry score is associated with operative approach for partial nephrectomy and urine leak. Urology. 2012;80:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell SC, Novick AC, Streem SB, et al. Complications of nephron sparing surgery for renal tumors. The Journal of urology. 1994;151:1177–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zorn KC, Gong EM, Orvieto MA, et al. Impact of collecting-system repair during laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. Journal of endourology / Endourological Society. 2007;21:315–320. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kundu SD, Thompson RH, Kallingal GJ, et al. Urinary fistulae after partial nephrectomy. BJU international. 2010;106:1042–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shindo S, Bernstein J, Arant BS., Jr Evolution of renal segmental atrophy (Ask-Upmark kidney) in children with vesicoureteric reflux: radiographic and morphologic studies. The Journal of pediatrics. 1983;102:847–854. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(83)80010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomaszewski JJ, Uzzo RG, Kutikov A, Hrebinko K, Mehrazin R, Corcoran AC, Ginzburg S, Viterbo R, Chen DYT, Greenberg RE, Smaldone MC. Assessing the burden of complications following surgery for clinically localized kidney cancer by age and co-morbidity status. Urology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer WA, Godoy G, Choi JM, et al. Higher RENAL Nephrometry Score is predictive of longer warm ischemia time and collecting system entry during laparoscopic and robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy. Urology. 2012;79:1052–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breau RH, Crispen PL, Jimenez RE, et al. Outcome of stage T2 or greater renal cell cancer treated with partial nephrectomy. The Journal of urology. 2010;183:903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]