Abstract

Objective

This study compared changes in emotion regulation and trait affect over the course of PTSD treatment with either prolonged exposure (PE) therapy or sertraline in adults with and without a history of childhood abuse (CA).

Method

Two hundred adults with PTSD received 10 weeks of PE or sertraline. Emotion regulation and trait affect were assessed at pre- and post-treatment and at six-month follow-up with the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003), the Negative Mood Regulation Scale (Catanzaro & Mearns, 1990), and the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988).

Results

Individuals with and without a history of CA did not differ from one another at pre-treatment on PTSD severity, emotion regulation, or positive/negative affect. In addition, treatment was effective at improving emotion regulation and trait affect in those with and without a history of CA, and no significant differences in emotion regulation or trait affect emerged at post-treatment or at six-month follow-up between adults with and without a history of CA. Furthermore, non-inferiority analyses indicated that the emotion regulation and trait affect outcomes of individuals with a history of CA were no worse than those of individuals without a history of CA.

Conclusion

These findings cast doubt on the assumption that CA is associated with worse emotion regulation following PTSD treatment, arguing against assertions that a history of CA itself is a contraindication for traditional PTSD treatment, and that there is a clear necessity for additional interventions designed at targeting assumed emotion regulation deficits.

Keywords: child abuse, emotion regulation, posttraumatic stress disorder, prolonged exposure, sertraline

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a debilitating disorder that develops in some individuals following exposure to a traumatic life event. Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and cognitive behavioral therapies, including prolonged exposure (PE) therapy, have been found to be efficacious in the treatment of chronic PTSD (e.g., Davis, Frazier, Williford, & Newell, 2006; Powers, Halpern, Ferenschak, Gillihan, & Foa, 2010), these treatments do not work with all clients. In fact, some claim that exposure therapy is inadequate for addressing the complex sequelae of childhood abuse (CA; e.g., Cloitre, Koenen, Cohen, & Han, 2002), including child sexual abuse, physical abuse, or both (Goldberg, Cloitre, Whiteside, & Han, 2003; Levitt & Cloitre, 2005; Stovall-McClough & Cloitre, 2006). These assertions, which may apply to both SSRIs and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), stem from findings indicating that one of the key problems associated with CA is impaired emotion regulation (e.g., Cloitre, Miranda, Stovall-McClough, & Han, 2005), which is the process that allows individuals to “influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express these emotions” (Gross, 1998, p. 275). For many individuals who have experienced CA, these emotion regulation deficits include difficulty recognizing and identifying emotions, managing emotional arousal, calming down, and letting go of distressing affective states (Roth, Newman, Pelcovitz, van der Kolk, & Mandel, 1997; Cloitre et al., 2005; Shipman et al., 2007).

Explanations for this association between CA and impairments in emotion regulation come from the developmental, behavioral neuroscience, and psychopathology literatures. Research from these areas suggests that there may be critical periods during childhood for learning how to properly respond to emotional stress (see Sánchez, Ladd, & Plotsky, 2001; Cicchetti & Toth, 1995, for reviews). Further, early life stress may be associated with neurobiological changes that may lead to later emotion dysregulation (see Heim & Nemeroff, 2001, for a review). Notably, pre-clinical research with animals has been instrumental in furthering understanding of the effects of early stress on emotion regulation. For example, in rodents, postnatal stress at two-weeks, but not three- or 10-weeks of age, has been shown to alter emotional responses to stress exhibited later in life (Matsumoto et al., 2005). These findings have led to the hypothesis that emotion regulation skills are acquired in humans initially during infancy and the preschool years (Widom, Kahn, Kaplow, Sepulveda-Kozakowski, & Wilson, 2007). Moreover, it is thought that CA during these early years, be it physical or sexual in nature, may affect children’s abilities to respond adaptively to emotional or stressful stimuli (e.g., Bremner, 2002) by interfering with key learning processes that are necessary for achieving the developmental task of regulating one’s emotions (van der Kolk, 2003).

Though the definition of CA varies from study to study, disturbances in emotion regulation are observed in adults who have experienced CA and in those who have undergone other prolonged forms of traumatic exposure (Roth et al., 1997; Cloitre et al., 2005; Frewen, Dozois, Neufeld, & Lanius, 2011), suggesting that CA and other kinds of chronic trauma exposure may have long-lasting effects on emotion regulation. Further, adults with a history of CA have been found to have moderately to substantially greater emotion regulation difficulties than those of individuals who have experienced trauma only in adulthood (e.g., Cloitre et al., 1997; Ehring & Quack, 2010; Kulkarni, Pole, & Timko, 2012). These studies are impressive in terms of their examination of not only PTSD symptoms, but also emotion regulation difficulties, in large samples of adults with and without histories of abuse. Although Ehring and colleagues (2010) found that these differences between those with and without a history of CA became non-significant after controlling for PTSD severity, it has been posited that the symptoms of adults with PTSD and a history of CA extend beyond the symptoms of PTSD and may include severe disturbances in emotion regulation (e.g., Ford, Courtois, Steele, van der Hart, & Nijenhuis, 2005). These disturbances may serve as critical barriers to the successful implementation of existing PTSD treatments (Zlotnick et al., 1997).

Given that PTSD treatment often encourages individuals to address disturbing emotions related to traumatic memories, some assume that a basic foundation of emotion regulation skills must be present in order to benefit from these treatments (Cloitre et al., 2002). Indeed, guidelines have been developed for treating what some term complex PTSD, which may result from CA and other chronic forms of trauma (Courtois, Ford, & Cloitre, 2009); though it is important to note that CA is not synonymous with complex PTSD and that not all those with a history of CA develop complex PTSD. These guidelines build off of the concerns of some that traditional forms of exposure therapy might overwhelm some patients due to a heightened risk for emotional instability, resulting in unsatisfactory emotion regulation outcomes (e.g., Zlotnick et al., 1997; Cloitre, Stovall-McClough, & Levitt, 2004; Ford et al., 2005). Consistent with this hypothesis is the finding that individuals with a history of CA, specifically child sexual abuse (CSA), have more PTSD symptoms following treatment with exposure therapy than do those without a history of CSA (Hembree, Street, Riggs, & Foa, 2004).

Three randomized controlled trials have shown that the addition of an emotion regulation skills component to exposure therapy for PTSD is effective at reducing PTSD symptoms and other difficulties in women with a history of CA. In the first two studies, Cloitre and colleagues found that a phase-based treatment consisting of both skills training in affect and interpersonal regulation (STAIR) and a modified form of prolonged exposure therapy (MPE) was more effective at improving PTSD symptoms and negative mood regulation than no treatment (Cloitre et al., 2002) and than both supportive counseling (SC) followed by MPE and STAIR followed by SC (Cloitre et al., 2010). In the third study, Steil, Dyer, Priebe, Kleindienst, and Bohust (2011) found that a residential form of dialectical behavior therapy for PTSD that included group skills training in mindfulness and in managing trauma-related emotions, as well as individual exposure treatment, was effective at reducing PTSD symptoms, trait anxiety, and depression.

However, it remains unclear whether phase-based treatments contribute to treatment effects on emotion regulation above and beyond those of exposure therapy alone (Cahill, Zoellner, Feeny, & Riggs, 2004; Ehring & Quack, 2010), as these treatments have yet to be compared to a full course of ten sessions of PE involving both imaginal and in vivo exposures. Furthermore, it is not clear that CA predicts worse outcome at post-treatment in the absence of additional targeted emotion regulation interventions. Specifically, Resick, Nishith, and Griffin (2003) found that women with a history of CSA fared as well as women without a history of CSA in terms of PTSD and other trauma reactions, including anxious arousal and anger-irritability, following treatment with either cognitive-processing therapy or PE. Similarly, McDonagh and colleagues found that, among women with PTSD and a history of CSA, those treated with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) were as likely as those treated with a problem-solving therapy tailored specifically for survivors of CSA to no longer meet criteria for PTSD following treatment (McDonagh et al., 2005). Although the dropout rate for CBT was higher than for problem-solving therapy, those in CBT were also less likely to have a diagnosis of PTSD at follow-up assessments than were those treated with problem-solving therapy. Additionally, individuals with PTSD subsequent to CA fared just as well as individuals without a history of CA in treatment with sertraline, showing marked improvement in PTSD symptom severity at post-treatment (Stein, van der Kolk, Austin, Fayyad, & Clary, 2006). Thus, these results suggest that non phase-based PTSD treatments may be effective in treating PTSD in adults with a history of CA.

Remarkably, however, no studies to date have examined whether PTSD treatment with CBT or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can improve the emotion regulation difficulties of adults with a history of CA. From a theoretical perspective, both treatments may be adequate for addressing the emotion regulation difficulties of these individuals. PE (Foa, Hembree, & Dancu, 2002; Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007), which is a type of CBT, directly and indirectly addresses many facets of emotion regulation, equipping patients with tools that might help them deal with intense emotions. Moreover, PE allows patients to experience in vivo that intense emotions associated with anxiety do not last indefinitely, but eventually subside, potentially teaching distress tolerance skills and facilitating inhibitory learning (Craske et al., 2008). Similarly, SSRIs may improve emotion regulation by acting through serotonergic pathways projecting from cortical regions, especially the orbitofrontal cortex, to key subcortical structures that have been implicated in emotional control processes, such as the amygdala (Cools, Roberts, & Robbins, 2008). Further, the SSRI, sertraline, has been found to improve emotion regulation (Davidson, Landerman, Farfel, & Clary, 2002; Simmons & Allen, 2011) and therefore may be an effective treatment for individuals suffering from both PTSD and emotion regulation difficulties.

The present study compared patients with and without a history of CA on key indices of emotion regulation and trait affect before and after receiving PTSD treatment with either PE or sertraline and at six-month follow-up. Notably, we took a multi-faceted approach to our examination of emotion regulation, assessing general emotion regulation and specific negative mood regulation, as well as positive and negative affect, which have been found to co-vary with emotion regulation (Saxena, Dubey, & Pandey, 2011). In addition, given the a priori hypothesis that individuals with and without CA would not differ on emotion regulation and trait affect outcomes, non-inferiority analyses were undertaken for non-significant differences. First, given that impaired emotion regulation has been associated not only with CA, but also with PTSD (Tull, Barrett, McMillan, & Roemer, 2007; Eftekhari, Zoellner, & Vigil, 2009; Lanius et al., 2010; Boden, Bonn-Miller, Kashdan, Alvarez, & Gross, 2012), we hypothesized that those with and without a history of CA would not differ in emotion regulation or trait affect at pre-treatment. Alternatively, if CA impairs emotion regulation (e.g., Cloitre et al., 1997; Kulkarni, Pole, & Timko, 2012), then those with CA should have greater emotion regulation difficulties and worse trait affect (i.e., lower positive affect, higher negative affect) than those without CA at pre-treatment. Second, given evidence suggesting that CA does not interfere with PTSD treatment (e.g., Resick, Nishith, & Griffin, 2003; Cahill et al., 2004; McDonagh et al., 2005; Stein, van der Kolk, Austin, Fayyad, & Clary, 2006), we predicted that the post-treatment and follow-up emotion regulation and trait affect outcomes of individuals with CA would not differ from those of individuals without CA. Further, we predicted that the emotion regulation outcomes for individuals with CA would be non-inferior to those for individuals without CA. However, if CA interferes with PTSD treatment (e.g., Zlotnick et al., 1997; Cloitre, Stovall-McClough, & Levitt, 2004; Ford et al., 2005), then those with CA should have worse emotion regulation and trait affect outcomes than those without CA.

Method

Participants

Two hundred participants were recruited from two large, metropolitan communities via referrals from providers in these communities and through advertising in buses, newspapers, and flyers placed in community centers, churches, grocery stores, convenience shops and libraries, and on campus message boards. Eligible participants were English-speaking men (24.5%, n = 49) and women (75.5%, n = 151) between the ages of 18 and 65 years old with a primary DSM-IV diagnosis of chronic PTSD related to a trauma that occurred at least three months prior to the initial evaluation. Exclusion criteria included: a current diagnosis of schizophrenia or delusional disorder; medically unstable bipolar disorder, depression with psychotic features, or depression requiring immediate psychiatric treatment; a diagnosis of alcohol or substance abuse within the previous three months; an ongoing intimate relationship with the perpetrator (in cases of sexual or physical assault); a change in the dose of psychiatric medication within the previous three months; an unwillingness to discontinue current antidepressant medication or psychotherapy; current use of sertraline; a previous, failed trial of either PE or sertraline; or a medical contraindication for taking sertraline, such as pregnancy or lactation.

A total of 426 individuals were screened for eligibility, of whom 172 were ineligible and 54 were eligible but declined study participation prior to randomization. The most common reasons for ineligibility were not meeting PTSD diagnostic criteria and a primary diagnosis other than PTSD. The remaining 200 individuals were provided with detailed treatment rationales for PE and sertraline and were randomized. Of those, 19 (9.5%) did not attend an initial treatment session. Individuals who did not follow through after hearing details about the treatment options did not differ from those who initiated treatment on CA indices, emotion regulation measures, or trait affect measures. The sample was primarily Caucasian (65.5%), with 21.5% African-Americans, and 13.0% of other backgrounds. The sample was predominantly female (75.5%) and not college educated (70%). The index trauma, defined as the trauma from which an individual’s current PTSD symptoms developed, reported by participants included sexual assault (31%), non-sexual assault (22.5%), childhood sexual abuse (17.5%), childhood non-sexual abuse (6.5%), a motor vehicle accident or some other kind of accident (13.5%), having a loved one die or be exposed to violence (6.5%), and combat or war (2.5%).

Approximately a quarter of participants reported CA as their index trauma (24%), and 65% (n = 170) of the participants reported having a history of CA, defined as either child sexual abuse or child physical abuse. Child sexual abuse was defined as one or more episodes of unwanted sexual contact (hand to genital or genital to genital) prior to the age of 13 by an individual five or more years older than the client. Child physical abuse was defined as one or more episodes prior to the age of 13 in which physical contact by an individual at least five years older than the client resulted in bruises or marks. For the full sample, the mean time since index trauma was 11.97 years (SD = 12.69, range .24 – 51.43 years) and the mean number of traumatic events participants reported experiencing over the course of their lives was 9.05 (SD = 6.23, range 0 – 26). The number of DSM-IV Criterion A lifetime traumatic events experienced was assessed using the trauma history section of the Standardized Trauma Interview (Foa, Hearst-Ikeda, Dancu, Hembree, & Jaycox, 1997; Foa, Rothbaum, Riggs, & Murdock, 1991). Given that many of the study participants endorsed having experienced one or more traumatic events “too many times to count” or “more than 100 times,” this maximum value of 26 traumatic events is based on the greatest exact count endorsed in the sample, plus the sample median value of five. Eighteen percent of the sample was stabilized on some form of psychotropic medication (e.g., lithium) other than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Measures

PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview Version (PSS-I; Foa et al., 1993)

The PSS-I is an interviewer-administered instrument that assesses the severity of the 17 DSM-IV PTSD symptoms on a 0 (not at all) to 3 (5 or more times per week/very much) scale. The PSS-I has good test-retest reliability (r = .80; Foa & Tolin, 2000). In the current study, diagnostic reliability was examined by rerating over 10% of the cases and was excellent (ICC = .985).

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders with Psychotic Screen (SCID-IV; First et al., 1995)

The SCID-IV is a semi-structured clinical interview that was used in the present study to assess for exclusion criteria and to assess for comorbid disorders. Over 10% of the cases from the current study were rerated for diagnostic reliability. There was good diagnostic agreement for current anxiety disorders (κ = 1.00, ppos = 1.00, pneg = 1.00), major depressive disorder (κ = .68, ppos = .88, pneg = .80), substance abuse disorders (ppos = .00, pneg = 1.00), and other diagnoses (ppos = .00, pneg = 1.00). In the present sample, 67.1% met criteria for another current Axis I disorder and 91.3%, lifetime.

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross & John, 2003)

The ERQ is a ten-item self-report measure of both cognitive reappraisal (i.e., cognitive attempts to dampen the emotional impact of situations) and expressive suppression (i.e., attempts to inhibit the expression of emotions). Items from both scales are assessed using 7-point Likert scales with scores ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with the mean score of the items on each scale being used as an indicator of reappraisal and suppression, respectively. Higher reappraisal is associated with more adaptive functioning, whereas higher suppression is associated with less adaptive functioning (Gross & John, 2003). The two subscales are only weakly correlated (r = −.01) and test-retest reliability is .69 for both scales (Gross & John, 2003).

Negative Mood Regulation (NMR; Catanzaro & Mearns, 1990)

The NMR is a 30-item self-report measure that assesses beliefs about one’s ability to effectively improve negative mood states using a 5-point Likert scale. Scores range from 1 (strong disagreement) to 5 (strong agreement), with higher scores reflecting better self-efficacy beliefs. The measure has both good internal consistency (.86 – .90) and temporal stability (.67 – .78; Catanzaro & Mearns, 1990).

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988)

The PANAS is a measure that consists of both positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) scales. In the present study, the trait version of the PANAS was used. The PA scale assesses the degree to which one experiences pleasant mood states such as excitement, inspiration, and pride; whereas, the NA scale assesses the extent to which one experiences unpleasant mood states such as nervousness, guilt, and disgust. The subscales contain 10 items each, and items are assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Test-retest reliability is .68 for PA and .71 for NA (Watson et al., 1988).

Treatment: Prolonged Exposure (PE)

Treatment with PE followed a standardized treatment manual (Foa, Hembree, & Dancu, 2002), and consisted of 10 weekly, 90–120 min sessions. Procedures included the following: education about common reactions to trauma; breathing retraining; repeated in vivo exposure; repeated imaginal exposure to the client’s trauma memory; processing of the trauma memory; and in vivo and imaginal exposure homework. All PE therapists were masters or PhD level clinicians who received standardized training in the delivery of PE. Weekly supervision occurred and included case discussions and video or audiotape review of the treatment sessions. Trained raters reviewed 10% of the session videotapes, providing integrity ratings, as well as PE therapist competence ratings (e.g., engaged in interactive exchange with the client) using a 3-point scale (1 = Inadequate, 2 = Okay, Mostly Adequate, 3 = Adequate or Better). PE therapists completed 90% of the essential components of PE and no protocol violations were observed. Additionally, overall PE therapist competence ratings were very good (M = 2.73, SD = .32).

Treatment: Sertraline

Pharmacotherapy with sertraline consisted of 10 weekly medication management sessions with board certified psychiatrists who were experienced in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Based on a treatment manual (Marshall, Beebe, Oldham, & Zaninelli, 2001), sessions lasted up to 30 min, with the first lasting up to 45 min. No exposure or anti-exposure instructions were given. Dosage started at 25 mg/day and if indicated and tolerated, increased to the goal of 200 mg/day, using a standard titration algorithm (Brady et al., 2000). Final average dosage was 115 mg/day (SD = 78.00). Medication adherence was documented with pill counts and medication diaries, and all sessions were recorded. Trained raters reviewed 10% of the videotapes, providing integrity ratings using the scale that Marshall et al. (2001) used. For essential components, psychiatrists completed 96% and no protocol violations were observed.

Procedures

After completing informed consent procedures, potential participants were interviewed by trained raters using the SCID-IV and the PSS-I. Eligible participants completed self-report questionnaires including the ERQ, NMR, and PANAS prior to randomization and then began acute treatment with either PE or sertraline. Participants again completed the ERQ, NMR, and PANAS at post-treatment and at six-month follow-up.

Data Analytic Strategy

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 19.0 (SPSS inc., Chicago). Pre-treatment continuous variables were analyzed using independent samples t-tests. In order to examine whether those with and without CA differed from one another at baseline, pre-treatment variables were compared for CA and no CA. Further, there were no differences between PE and sertraline on these variables at pre-treatment. To examine whether CA moderates the effects of treatment (PE vs SER) and time (pre-, post-treatment, 6-month follow-up) on emotion regulation (ERQ, NMR) and trait affect (PANAS), linear mixed effects models were used with a random intercept model, which provided the best fit for the data. Analyses were intent-to-treat, using Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) for handling missing data.

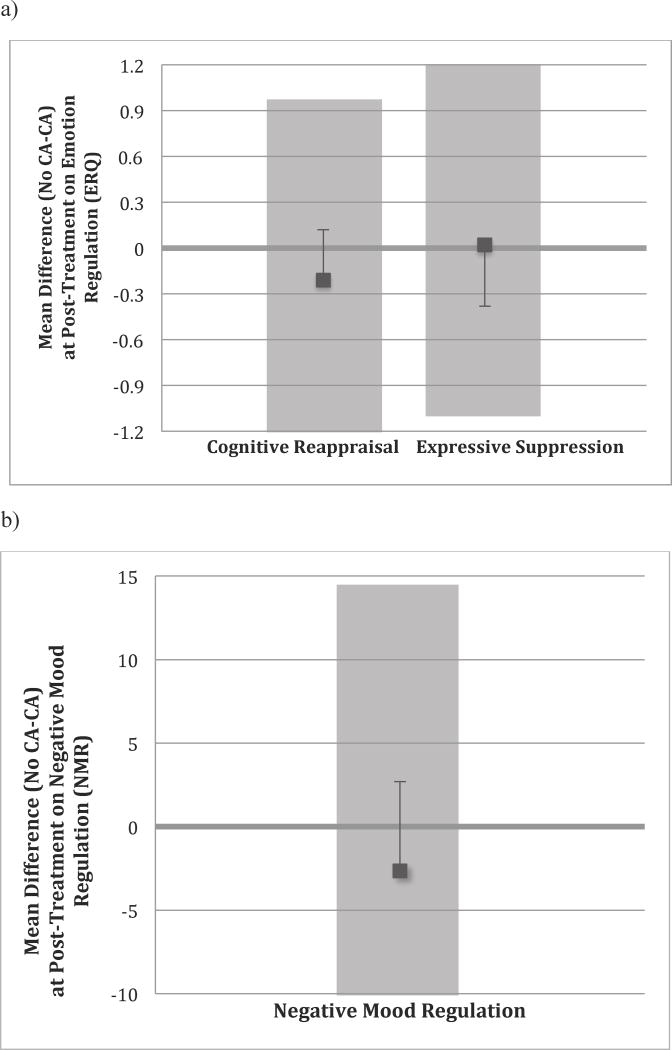

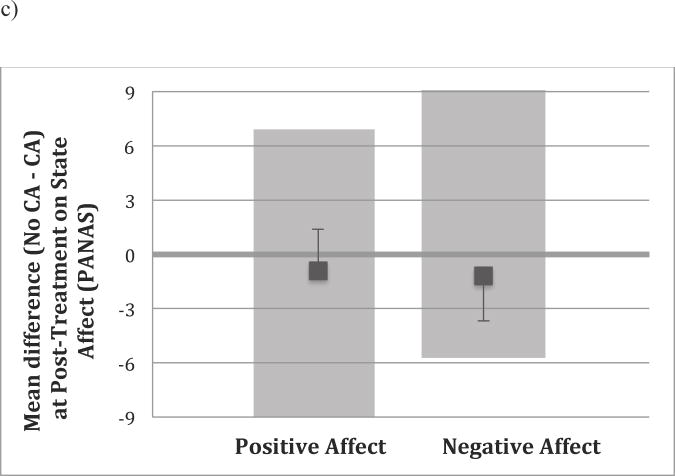

Non-significant findings were followed up with non-inferiority analyses (Pocock, 2003), which allowed us to examine whether the emotion regulation and trait affect outcomes of individuals with a history of CA were clinically non-inferior to those of individuals without a history of CA (Wellek, 2010). Non-inferiority margins (Wellek, 2010) were determined a priori on the basis of statistical reasoning and clinical judgment (Kaul & Diamond, 2006) using the standard deviations of healthy samples, which provided a conservative benchmark for healthy post-treatment responding. For the ERQ reappraisal and suppression scales, the non-inferiority margins were set at [−∞, 1] and [−1.16, ∞], respectively. These values were derived by weighting the standard deviations by gender of the healthy sample (Gross & John, 2003). The non-inferiority margins were similarly set for the NMR [−∞, 14.33], positive affect [−∞, 6.40], and negative affect [−5.90, ∞] (Catanzaro & Mearns, 1990; Watson et al., 1988). One-sided 95% confidence intervals, α = .05, were calculated for the difference between the emotion regulation outcomes for no CA and CA at post-treatment and at six-month follow-up. For cognitive reappraisal, negative mood regulation, and positive affect, positive values would indicate that those with a history of CA had worse outcomes than those without a history of CA. Conversely, for expressive suppression and negative affect, negative values would indicate that those with a history of CA had worse outcomes than those without a history of CA.

Results

Pre-treatment Differences on Childhood Abuse

We then examined whether those with CA differed from those without CA in terms of baseline severity, as measured by the PSS-I, ERQ, NMR, and PANAS. Individuals with a history of CA (M = 29.76, SD = 6.73) did not differ from those without a history of CA (M = 29.21, SD = 6.64) in terms of baseline PTSD severity; t(198) = −0.55, p = .62. As seen in Table 1, there also were no differences between groups on emotion regulation, as assessed by cognitive reappraisal, t(192) = 0.09, p = .37, expressive suppression, t(192) = −0.57, p = .63, and negative mood regulation, t(169) = −1.12, p = .52. In addition, there were no differences between groups on trait affect, as assessed by positive affect, t(191) = −1.70, p = .75, and negative affect, t(191) = 0.05, p = .64. Thus, there were no pre-treatment differences between those with and without a history of CA on PTSD severity, emotion regulation, or trait affect. See Table 1 for pre-treatment emotion regulation and trait affect means, as well as for effect sizes of the pre-treatment differences between those with and without a history of CA. The pattern of findings did not differ when examining PTSD specific to CA rather than a history of CA.1

Table 1.

Emotion Regulation at Pre- and Post-treatment and at Six-Month Follow-up and Mean Effect Size Difference between No CA and CA at Pre- and Post-Treatment and at Six-Month Follow-up

| Measure | No CA (n = 70) | CA (n = 130) | No CA Minus CA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Tx | Post-Tx | 6-Mo | Pre-Tx Minus Post-Tx |

Pre-Tx Minus 6- Mo |

Pre-Tx | Post-Tx | 6-Mo | Pre-Tx Minus Post-Tx |

Pre-Tx Minus 6- Mo |

Pre-Tx | Post-Tx | 6-Mo | |

| M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

Effect Size (d) |

Effect Size (d) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

Effect Size (d) |

Effect Size (d) |

Effect Size (d) |

Effect Size (d) |

Effect Size (d) |

|

| ERQ Rea | 4.32 (1.21) | 4.53 (1.34) | 4.61 (1.56) | 0.16 | 0.21 | 4.32 (1.22) | 4.74 (1.41) | 4.54 (1.51) | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.05 |

| ERQ Sup | 3.97 (1.32) | 3.59 (1.46) | 3.56 (1.68) | 0.27 | 0.27 | 4.13 (1.33) | 3.57 (1.52) | 3.18 (1.63) | 0.39 | 0.64 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.23 |

| NMR | 93.05 (20.72) | 105.16 (21.92) | 107.73 (24.43) | 0.57 | 0.65 | 95.70 (20.64) | 107.82 (21.79) | 108.58 (23.44) | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.04 |

| PA | 30.07 (8.26) | 35.22 (9.35) | 30.47 (9.27) | 0.58 | 0.05 | 32.09 (8.40) | 36.14 (9.47) | 30.80 (8.90) | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| NA | 29.4 (8.95) | 20.33 (10.18) | 24.43 (10.05) | 0.95 | 0.53 | 29.60 (9.12) | 21.52 (10.32) | 25.07 (9.60) | 0.83 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.07 |

Note. ERQ Rea = Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, Cognitive Reappraisal Subscale; ERQ Sup = Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, Expressive Suppression Subscale; NMR = Negative Mood Regulation; PA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Positive Affect Subscale; NA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale, Negative Affect Subscale.

Childhood Abuse as a Moderator of Time and Treatment Outcome

Next, to test the hypothesis that CA moderates treatment outcome, we used multilevel modeling to examine the two-way interaction between CA (present vs absent) and Time (pre-, post-, six-month follow-up). There was no CA x Time interaction for emotion regulation, as assessed by cognitive reappraisal, F(1, 447) = .05, p = .83, expressive suppression, F(1, 449) = 0.36, p = .55, and negative mood regulation, F(1, 280.91) = 0.78, p = .78. Further, there was no CA x Time interaction for trait affect, as assessed by positive affect, F(1, 315.47) = 0.61, p = .44, and negative affect, F(1, 312.71) = 0.27, p = .61. Thus, CA did not moderate the effect of time on emotion regulation or trait affect. The pattern of findings did not differ when examining PTSD specific to CA rather than a history of CA.2 See Table 1 for emotion regulation and trait affect effect sizes comparing No CA to CA.

To examine whether CA moderated the effect of either PE or sertraline over time, we examined the three-way interaction among CA (CA vs no CA), treatment (PE vs sertraline), and time (pre-, post-, six-month follow-up), on emotion regulation and trait affect. There were no three-way interactions for cognitive reappraisal, F(1, 447) = .33, p = .56, expressive suppression, F(1, 449) = 0.14, p = .71, or negative mood regulation, F(1, 280.91) = 0.48, p = .49. Further, there were no three-way interactions for positive affect, F(1, 315.47) = 1.68, p = .20, or negative affect, F(1, 312.71) = 0.02, p = .88. Thus, CA did not moderate the emotion regulation or trait affect treatment outcomes following treatment with either PE or sertraline. The general pattern of findings did not differ when examining PTSD specific to CA rather than a history of CA, though there was some indication, for those with CA specific PTSD, that PE was more effective than sertraline in reducing negative affect.3

Non-inferiority of Childhood Abuse at Post-Treatment and Six-month Follow-up

Given that a history of CA did not moderate change in emotion regulation or trait affect at post-treatment or at six-month follow-up according to conventional superiority tests, we further examined whether the emotion regulation outcomes of those with a history of CA were non-inferior to the outcomes of those without a history of CA. That is, were the emotion regulation and trait affect outcomes of individuals with a history of CA no worse than those of individuals without a history of CA at post-treatment and at six-month follow-up? Given that the main a priori hypotheses were not treatment specific and no differential effects were observed on CA for PE and sertraline, these analyses were collapsed across PE and sertraline. To do so, we examined the one-sided, 95% confidence intervals of the difference between the emotion regulation and trait affect outcomes for No CA and CA at post-treatment and at six-month follow-up. As illustrated for post-treatment data in Figure 1, which depicts the mean difference between No CA and CA, as well as the 95% confidence intervals and the non-inferiority margins for cognitive reappraisal, expressive suppression, negative mood regulation, positive affect, and negative affect, the emotion regulation and trait affect outcomes for individuals with a history of CA were not inferior to those of individuals without a history of CA. More specifically, for both post-treatment and follow-up, the confidence values fell within the pre-set, non-inferiority margins for reappraisal, 95% CI [−∞, 1.22], suppression, 95% CI [−0.382, ∞], negative mood regulation, 95% CI [−∞, 2.681], positive affect, 95% CI [−∞, 1.380], and negative affect, 95% CI [−3.689, ∞]. Thus, across all measures, individuals with CA were not worse in emotion regulation or trait affect at post-treatment or at six-month follow-up than individuals without CA.

Figure 1. Non-inferiority Margins and One-sided 95% CIs for Differences in Outcome Between Those With and Without a History of CA.

Note. Figures 1a, 1b, and 1c represents the non-inferiority margins and one-sided 95% CIs for the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), Negative Mood Regulation (NMR) scale, and Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS), respectively. The shaded regions are the non-inferiority margins. The line at zero represents where the mean difference (No CA-CA) would be if there were no difference between those with and without a history of CA at post-treatment. The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval of the mean difference. In order to reject the non-inferiority hypothesis, the error bars would have to be outside of the shaded region. CA = childhood abuse; No CA = no childhood abuse.

Discussion

The present study examined emotion regulation and trait affect in individuals with and without a history of CA before and after PTSD treatment with either PE or sertraline and at six-month follow-up. There were no baseline differences in PTSD severity, emotion regulation, or trait affect between those with and without a history of CA. Further, emotion regulation and trait affect both improved over time for those with and without a history of CA. Post-treatment and follow-up emotion regulation and trait affect outcomes of those with a history of CA were functionally the same as the outcomes of those without a history of CA. Notably, these findings were seen across measures of general and negative mood emotion regulation, as well as measures of positive and negative trait affect. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that individuals with a history of CA improve over the course of standard, evidenced-based treatment. Further, these findings suggest that among a sample of treatment-seeking individuals with PTSD, a history of CA need not necessarily be seen as a red flag for poor emotion regulation. Similarly, these findings indicate that a history of CA does not, by itself, necessitate the addition of targeted emotion regulation interventions to existing PTSD treatments.

The current study is novel in that it is, to our knowledge, the first to examine whether individuals with and without a history of CA differ in emotion regulation and trait affect before and after receiving treatment for PTSD. Although prior studies have focused on the effects of CA on post-treatment PTSD symptoms rather than on emotion regulation and trait affect, the results of the present study fit with previous findings suggesting that clients with and without a history of CA benefit similarly from treatment with either CBT or SSRIs (e.g., Resick et al., 2003; Stein et al., 2006). Further, the results of this study are consistent with previous findings suggesting that CA is not a reliable predictor of poorer PTSD treatment outcome (van Minnen, Arntz, & Keijsers, 2002; Karatzias et al. 2007). Accordingly, the current study’s findings lend support to the notion that CA should not be viewed as a contraindication for the use of exposure therapy to treat PTSD (Cahill et al., 2004; Hembree & Brinen, 2009).

Conversely, the findings of the present study contrast with previous research suggesting that those with a history of CA have elevated PTSD symptoms and greater emotion regulation impairments compared to trauma survivors without a history of CA. However, unlike previous studies, which examined PTSD symptoms and emotion regulation in trauma-exposed individuals who may or may not have had PTSD (Cloitre et al., 1997; Ehring & Quack, 2010; Kulkarni et al., 2012), the current study’s findings are based on a sample of individuals who had a primary diagnosis of PTSD and who were seeking treatment for their PTSD symptoms. In addition, although the current findings are inconsistent with the finding that CSA predicts worse PTSD outcomes following treatment with PE (Hembree et al., 2004), this discrepancy may be a reflection of different samples, outcome measures, and comparison treatments. Specifically, the present study included a sample of both men and women with heterogeneous trauma exposure, whereas Hembree et al. (2004) only examined assault-related trauma in women. Thus, it may be that within a homogenous sample, a history of CA emerges as a predictor of treatment outcome, but that within more heterogeneous samples, the differential predictive value of CA history disappears. Further, Hembree and colleagues (2004) assessed PTSD rather than emotion regulation and collapsed the treatment outcomes of those who received PE, stress inoculation training (SIT), and combined PE and SIT.

In addition, the moderate to large effect sizes found in the present study for those with a history of CA are not in line with the hypothesis that existing PTSD treatments are insufficient for improving emotion regulation in individuals with a history of CA (e.g., Cloitre et al., 2004). Indeed, it is likely that we would have seen even greater changes in emotion regulation had we specifically selected for individuals with baseline deficits in emotion regulation. Relatedly, the study’s main findings call into question claims that PTSD treatment for adults with a history of CA must explicitly include targeted emotion regulation interventions (e.g., Ford et al., 2005; Cloitre et al., 2011). In addition to presenting for treatment with similar emotion regulation abilities, individuals with and without a history of CA also showed positive changes in emotion regulation and trait affect following treatment with either PE or SSRIs, even though these treatments do not necessarily target either emotion regulation or trait affect. Furthermore, although it is possible that additional interventions could augment standard, evidenced-based PTSD treatment for individuals with a history of CA, there is no data to suggest that the addition of targeted emotion regulation interventions to PTSD treatment results in outcomes that are superior to those of stand alone PTSD treatments. Indeed, the only trial that has compared an augmented treatment of this nature to an existing PTSD treatment used a modified version of PE that did not include in vivo exposure. Moreover, given that the post-treatment negative mood regulation means from the present study for those with a history of CA were within one standard deviation of the means that Cloitre and colleagues obtained following their phase-based treatment for CA-related PTSD (Cloitre et al., 2002; 2010), it further raises doubts regarding whether individuals with PTSD with a history of CA benefit more from an emotion regulation skills augmented PTSD treatment than from standard PTSD treatment.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be noted. First, our sample was predominantly Caucasian and female and thus it is unclear as to whether these findings would generalize to more diverse samples of individuals seeking treatment for PTSD. Second, it is possible that the sample we selected of individuals with a history of CA was not representative of the general population of survivors of CA but instead was positively skewed in terms of pre-treatment emotion regulation and trait affect. However, this seems unlikely given that the pre-treatment NMR means of those in the current study were similar to the pre-treatment NMR means found in previous studies of individuals with a history of CA presenting for PTSD treatment (e.g., Cloitre et al., 2002; 2010). Third, given that a primary diagnosis of PTSD was one of our inclusion criteria, individuals with the most severe impairments in emotion regulation, such as those with a primary diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD), were excluded from the study. However, the study’s inclusion criteria were chosen in order to ensure that clients received the most appropriate clinical care given their presenting problems, as we believe that those with a primary diagnosis of BPD should be treated initially with treatment that targets BPD (Harned, Jackson, Comtois, & Linehan, 2010). Fourth, we assessed CA as a unitary construct despite theoretical arguments that CA during certain critical, early periods of development may lead to greater disturbances in emotion regulation than CA during later developmental periods (Widom et al., 2007). However, we chose to define CA as it is commonly defined, both clinically and in the current literature (e.g., Cloitre et al., 2010). In addition, we expanded upon previous investigations by not only comparing those with and without a history of CA, but also by examining whether CA was the target of PTSD treatment. Finally, this study lacked a wait-list condition, making it difficult to rule out the possibility that the observed improvements in emotion regulation and trait affect were an artifact of time. Yet, this seems unlikely given that the mean time since participants’ index trauma was over 11 years and that previous studies have failed to show improvements in PTSD symptoms over time alone (e.g., Rothbaum, Astin, & Marsteller, 2005; Stein et al., 2006).

The current findings are important in that they provide evidence that counters three common assumptions in the literature: 1) that individuals with PTSD and a history of CA have greater emotion regulation deficits than those without CA; 2) that individuals with a history of CA fare worse than individuals without a history of CA in terms of emotion regulation following standard, evidenced-based PTSD treatments; and 3) that existing PTSD treatments must be augmented with interventions that explicitly target emotion regulation. Additionally, the findings have potential clinical implications for clients with a history of CA who cannot afford the time or cost of longer, phase-based treatments, as well as for practitioners who worry that clients with a history of CA are not appropriate candidates for shorter, evidenced-based PTSD treatments. Additional research is needed, however, before any conclusions can be made regarding the superiority, equivalence, or non-inferiority of phase-based treatments to standard PTSD treatment. Furthermore, future research should move away from assessing CA as a monolithic entity and should instead assess whether and how the effects of CA on emotion regulation vary depending on the age at which the abuse occurred as well as the frequency and chronicity of the abuse. Doing so will be crucial in enabling us to respond to calls for the mental health field to find the best treatment approaches for individual patients given their particular characteristics and circumstances (Insel, 2009).

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported in part by NIH grants R01MH066347 and R01MH066348.

Footnotes

We re-ran these analyses for individuals with and without an index trauma of CA. An index trauma refers to the traumatic event from which the individual’s current PTSD symptoms developed. The results from these analyses did not differ from the main analyses. Individuals with an index trauma of CA (M = 29.15, SD = 6.99) did not differ significantly from those without (M = 29.69, SD = 6.61) in terms of baseline PTSD severity; t(198) = 0.48, p = .63. Moreover, individuals with an index trauma of CA (M = 4.36, SD = 1.17) did not differ from individuals without (M = 4.31, SD = 1.17) in terms of baseline cognitive reappraisal, t (192) = 0.81, p = .81. Individuals with an index trauma of CA (M = 4.22, SD = 1.22) also did not differ from individuals without (M = 4.03, SD = 1.33) in terms of expressive suppression, t(192) = −0.81, p = 0.42. There was also no difference between individuals with an index trauma of CA (M = 92.86, SD = 14.51) and those without (M = 95.49, SD = 19.82), in terms of negative mood regulation, t(169) = 0.75, p = .45. Similarly, individuals with an index trauma of CA (M = 33.14, SD = 8.28) did not differ from individuals without an index trauma of CA (M = 30.80, SD = 7.86) in terms of positive affect, t(191) = −1.70, p = .09. Further, individuals with an index trauma of CA (M = 31.33, SD = 8.48) did not differ from those without (M = 29.08, SD = 8.49) in terms of negative affect, t(191) = −1.54, p = .13.

For individuals with and without an index trauma of CA, there was not an index CA x Time interaction for cognitive reappraisal, F(1, 447) = 0.04, p = .84, expressive suppression, F(1, 449) = 0.14, p =.71, negative mood regulation, F(1, 287.46) = 0.00, p = .99, positive affect, F(1, 313.29) = 1.25, p = .27, or negative affect, F(1, 312.02) = 2.39, p = .12.

We reran the linear mixed effects models for individuals with and without an index trauma of CA and found no index CA x Treatment x Time interactions for cognitive reappraisal, F(1, 447) = .54, p = 0.46, expressive suppression, F(1, 449) = 0.21, p = .65, negative mood regulation, F(1, 287.46) = 3.80, p = .05. However, the three-way interactions for both positive affect, F(1, 313.29) = 4.10, p = .04, and negative affect, F(1, 312.02) = 5.12, p = .02, achieved significance. For positive affect, when examining an index trauma of CA and no index trauma of CA separately, there was no significant Treatment x Time interaction for either no index trauma of CA, F(1, 241.94) = 1.51, p = .22, or index trauma of CA, F(1, 70.53) = 2.49, p = .12. For negative affect, when examining an index trauma of CA and no index trauma of CA separately, a significant Treatment x Time interaction was not present for no index trauma of CA, F(1, 245.55) = 0.05, p = .83, but was present for an index trauma of CA, F(1, 65.52) = 5.74, p = .02. For those with an index trauma of CA, there was an effect of time for PE, F(1, 46.49) = 3.75, p = .06, and for sertraline, F(1, 19.04) = 11.09, p = .004.

Contributor Information

Alissa B. Jerud, University of Washington.

Lori A. Zoellner, University of Washington.

Larry D. Pruitt, University of Washington.

Norah C. Feeny, Case Western Reserve University.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. (Revised 4th ed.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD. Neuroimaging of childhood trauma. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2002;7:104–112. doi: 10.1053/scnp.2002.31787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady K, Pearlstein T, Asnis GM, Baker D, Rothbaum B, Sikes CR, Farfel GM. Efficacy and safety of sertraline treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:1837–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Luu P, Posner MI. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4:215–222. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill SP, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC, Riggs DS. Sequential treatment for child abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder: methodological comment on Cloitre, Koenen, Cohen, and Han (2002) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:543–548. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzaro SJ, Mearns J. Measuring generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation: Initial scale development and implications. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990;54:546–563. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5403&4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:541–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Courtois CA, Charuvastra A, Carapezza R, Stolbach BC, Green BL. Treatment of complex PTSD: Results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24:615–627. doi: 10.1002/jts.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Koenen KC, Cohen LR, Han H. Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1067–1074. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.5.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Miranda R, Stovall-McClough KC, Han H. Beyond PTSD: Emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:119–124. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80060-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Scarvalone P, Difede J. Posttraumatic stress disorder, self- and interpersonal dysfunction among sexually retraumatized women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:437–452. doi: 10.1023/A:1024893305226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, van der Kolk B, Pynoos R, Wang J, Petkova E. A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22:399–408. doi: 10.1002/jts.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stovall-McClough C, Zorbas P, Charuvastra A. Attachment organization, emotion regulation, and expectations of support in a clinical sample of women with childhood abuse histories. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:282–289. doi: 10.1002/jts.20339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stovall-McClough KC, Levitt JT. Treating life-impairing problems beyond PTSD: Reply to Cahill, Zoellner, Feeny, and Riggs (2004) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:549–551. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stovall-McClough KC, Nooner K, Zorbas P, Cherry S, Jackson CL, Gan W, et al. Treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse: A randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:915–924. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, Roberts AC, Robbins TW. Serotoninergic regulation of emotional and behavioural control processes. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2008;12:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Kircanski K, Zelikowsky M, Mystkowski J, Chowdhury N, Baker A. Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:5–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois CA, Ford JD, Cloitre M. Best practices in psychotherapy for adults. In: Courtois CA, Ford JD, editors. Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based guide. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 82–103. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Landerman LR, Farfel GM, Clary CM. Characterizing the effects of sertraline in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:661–670. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702005469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LL, Frazier EC, Williford RB, Newell JM. Long-term pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:465–476. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200620060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eftekhari A, Zoellner LA, Vigil SA. Patterns of emotion regulation and psychopathology. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal. 2009;22:571–586. doi: 10.1080/10615800802179860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, Quack D. Emotion regulation difficulties in trauma survivors: The role of trauma type and PTSD symptom severity. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV) Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hearst-Ikeda D, Dancu CV, Hembree EA, Jaycox LJ. The Standardized Assault Interview. Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety; 3535 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104: 1997. Appendix in Prolonged Exposure Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Dancu CV. Prolonged Exposure (PE) Manual: Revised Version. 2002. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Rothbaum BO. Treatments that work. New York, NY US: Oxford University Press; 2007. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences: Therapist guide. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490060405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Rothbaum BO, Riggs DS, Murdock TB. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:715–723. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Courtois CA, Steele K, van der Hart O, Nijenhuis ERS. Treatment of complex posttraumatic self-dysregulation. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:437–447. doi: 10.1002/jts.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen PA, Dozois DJA, Neufeld RWJ, Lanius RA. Disturbances of emotional awareness and expression in posttraumatic stress disorder: Meta-mood, emotion regulation, mindfulness, and interference of emotional expressiveness. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2012;4:152–161. doi: 10.1037/a0023114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JF, Cloitre M, Whiteside JE, Han H. An open-label pilot study of divalproex sodium for posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood abuse. Current Therapeutic Research. 2003;64:45–54. doi: 10.1016/S0011-393X(03)00003-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, New directions in research on emotion. 1998;2:271–299. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harned MS, Jackson SC, Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy as a precursor to PTSD treatment for suicidal and/or self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:421–429. doi: 10.1002/jts.20553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: Preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01157-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembree EA, Brinen AP. Prolonged exposure (PE) for treatment of childhood sexual abuse-related PTSD: Do we need to augment it? Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy. 2009;5:35–44. Retrieved from: http://www.pcsp.libraries.rutgers.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Hembree EA, Street GP, Riggs DS, Foa EB. Do assault-related variables predict response to cognitive behavioral treatment for PTSD? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:531–534. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR. Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: A strategic plan for research on mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:128–133. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatzias A, Power K, McGoldrick T, Brown K, Buchanan R, Sharp D, Swanson V. Predicting treatment outcome on three measures for post-traumatic stress disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2007;257:40–46. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0682-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni M, Pole N, Timko C. Childhood victimization, negative mood regulation, and adult PTSD severity. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0027746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lanius RA, Bluhm RL, Frewen PA. How understanding the neurobiology of complex post-traumatic stress disorder can inform clinical practice: a social cognitive and affective neuroscience approach. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2011;124:331–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Loewenstein RJ, Brand B, Schmahl C, Bremner JD, Spiegel D. Emotion Modulation in PTSD: Clinical and Neurobiological Evidence for a Dissociative Subtype. The American journal of psychiatry. 2010;167:640–647. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt JT, Cloitre M. A clinician’s guide to STAIR/MPE: treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2005;12:40–52. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(05)80038-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RD, Beebe KL, Oldham M, Zaninelli R. Efficacy and safety of paroxetine treatment for chronic PTSD: A fixed-dose, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1982–1988. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Higuchi K, Togashi H, Koseki H, Yamaguchi T, Kanno M, Yoshioka M. Early postnatal stress alters the 5-HTergic modulation to emotional stress at postadolescent periods of rats. Hippocampus. 2005;15:775–781. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh A, Friedman M, McHugo G, Ford J, Sengupta A, Mueser K, Demment CC, et al. Randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:515–524. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, Gillihan SJ, Foa EB. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Griffin MG. How well does cognitive-behavioral therapy treat symptoms of complex PTSD? An examination of child sexual abuse survivors within a clinical trial. CNS Spectrums. 2003;8:340–355. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900018605. Retrieved from: http://www.cnsspectrums.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Newman E, Pelcovitz D, van der Kolk B, Mandel FS. Complex PTSD in victims exposed to sexual and physical abuse: Results from the DSM-IV field trial for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:539–555. doi: 10.1023/A:1024837617768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Astin MC, Marsteller F. Prolonged exposure versus eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for PTSD rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:607–616. doi: 10.1002/jts.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez MM, Ladd CO, Plotsky PM. Early adverse experience as a developmental risk factor for later psychopathology: Evidence from rodent and primate models. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:419–449. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003029. http://dx.doi.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena P, Dubey A, Pandey R. Role of emotion regulation difficulties in predicting mental health and well-being. Journal of Projective Psychology & Mental Health. 2011;18:147–155. Retrieved from: http://www.somaticinkblots.com/SISJournal/tabid/61/Default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Shipman KL, Schneider R, Fitzgerald MM, Sims C, Swisher L, Edwards A. Maternal emotion socialization in maltreating and non-maltreating families: Implications for children’s emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:268–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00384.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons JG, Allen NB. Mood and personality effects in healthy participants after chronic administration of sertraline. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;134:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli S, Chefer S, Suomi SJ, Higley JD, Barr CS, Stein E. Early-life stress induces long-term morphologic changes in primate brain. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:658. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steil R, Dyer A, Priebe K, Kleindienst N, Bohus M. Dialectical behavior therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood sexual abuse: A pilot study of an intensive residential treatment program. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24:102–106. doi: 10.1002/jts.20617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Van Der Kolk BA, Austin C, Fayyad R, Clary C. Efficacy of sertraline in posttraumatic stress disorder secondary to interpersonal trauma or childhood abuse. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;18:243–249. doi: 10.1080/10401230600948431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stovall-McClough KC, Cloitre M. Unresolved attachment, PTSD, and dissociation in women with childhood abuse histories. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:219–228. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk BA. The neurobiology of childhood trauma and abuse. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2003;12:293–317. ix. doi: 10.1016/S1056-4993(03)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Minnen A, Arntz A, Keijsers GPJ. Prolonged exposure in patients with chronic PTSD: predictors of treatment outcome and dropout. Behaviour research and therapy. 2002;40:439–457. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellek S. Testing Statistical Hypotheses of Equivalence and Noninferiority, Second Edition. 2. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Kahn EE, Kaplow JB, Sepulveda-Kozakowski S, Wilson HW. Child abuse and neglect: Potential derailment from normal developmental pathways. NYS Psychologist, Innovations and interventions. 2007;19:2–6. Retrieved from: http://nyspa.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=837:nys-psychologist&catid=9:uncategorised. [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Shea TM, Rosen K, Simpson E, Mulrenin K, Begin A, Pearlstein T. An affect-management group for women with posttraumatic stress disorder and histories of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:425–436. doi: 10.1023/A:1024841321156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]