Abstract

Although developmental research continues to connect parenting behaviors with child outcomes, it is critical to examine how child behaviors influence parenting behaviors. Given the emotional, cognitive, and social costs of maladaptive parenting, it is vital to understand the factors that influence maternal socialization behaviors. The current study examines children’s observed emotion regulatory behaviors in two contexts (low-threat and high-threat novelty) as one influence. Mother-child dyads (n = 106) with toddlers of 24 months of age participated in novelty episodes from which toddler emotion regulation behaviors (caregiver-focused, attention, and self-soothing) were coded, and mothers reported their use of emotion socialization strategies when children were 24 and 36 months. We hypothesized that gender-specific predictive relations would occur, particularly from regulatory behaviors in the low-threat contexts. Gender moderated the relation between caregiver-focused emotion regulation in low-threat contexts and non-supportive emotion socialization. Results from the current study inform the literature on the salience of child-elicited effects on the parent-child relationship.

Keywords: emotion regulation, emotion socialization, parenting, toddlers, gender

Emotion regulation and emotion socialization are crucial and formative emotional processes that have been found to influence both individual socioemotional outcomes in children as well as the quality of parent-child relationships (Eisenberg, Fabes, & Murphy, 1996; Malatesta-Magai, 1989). Children’s emotion regulation has been most frequently studied as an outcome of maternal behavior (Morris et al., 2002; Shipman & Zeman, 2001; Eisenberg et al. 2001) or as a predictor of children’s own outcomes (Cole, Zahn-Waxler, Fox, Usher, & Welsh, 1996; Eisenberg et al., 1997; Walden, Lemerise, & Smith, 1999). Its role as a predictor of maternal behavior remains understudied. Relatedly, although maternal emotion socialization has been studied as a predictor of child outcomes (Eisenberg, Fabes, Carlo, & Karbon, 1992; Eisenberg et al., 1996), children’s effects on emotion socialization remain largely unknown. Given recent support for transactional models of development, it is important to investigate child-driven effects between these emotion processes. By examining toddler emotion regulation at age 2 as a predictor of maternal emotion socialization at age 3 longitudinally, the current study contributes to the growing literature on how children affect the parenting they receive, specifically within the realm of emotional processes. Furthermore, toddler gender provides an important context in which to understand parent-child interactions, as parents respond to boys’ and girls’ emotions (and potentially their regulation behaviors) differently (Eisenberg et al., 2001; Fivush & Buckner, 2000), so we consider toddler gender as a moderator of this predictive relation.

Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation refers to the initiation, maintenance, and modulation of emotional arousal in order to support individual goals and effectively adapt to one’s social environment (Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004). This can occur through both external and internal processes (Morris et al., 2007). In children, emotion regulation is encompassed in self-regulation, an active process developing throughout toddlerhood that relies both on internal mechanisms, like genetic heritability and temperament, and external processes such as parenting (Sroufe, 1996).

Toddlerhood is a significant developmental period for children’s navigation between externally- and internally-managed emotion regulation. For infants, emotion regulation is primarily managed externally by caregivers, while for school-aged children, adolescents, and adults, “self” emotion regulation is dominant (Kopp, 1982, 1989; Eisenberg, Spinrad & Morris, 2002; Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003). Due to cognitive and emotional advances in toddlerhood, children transition between relying on their caregivers and more independent strategies to regulate, so a variety of caregiver-focused and independent behavioral strategies would be expected to be observed (Grolnick, Bridges, & Connell, 1996). In this age group, caregiver-focused or “other-directed” regulation is characterized by contact seeking (e.g., reaching for or running toward their caregiver) and looking to their caregivers (e.g., social referencing; Ainsworth & Wittig, 1969; Grolnick et al., 1996). Independent regulation behaviors include self-soothing behaviors such as self-touching, self-stimulation (e.g., rhythmic, often unconscious touching or rubbing), and fidgeting (e.g., squirming), as well as attention-related behaviors, like gaze aversion and distraction (Goldsmith & Rothbart, 1996; Kopp, 1989; Mangelsdorf, Shapiro, & Marzolf, 1995; Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981). Whether they are caregiver-focused or more independent, regulatory behaviors have been theorized to be separable from, and therefore not interchangeable with emotion expression, which may be indicative of the distress these behaviors regulate (Cole et al., 2004). When expression and regulation have been measured distinctly, these aforementioned regulatory behaviors have been found to regulate negative affect in young children during observed emotion reactivity studies (Cole et al., 2004; Rothbart & Bates, 1998). Important for the current study, children’s regulatory behaviors may inform parenting outcomes above and beyond children’s expressed emotion or its valence, suggesting a unique contribution of children’s specific regulatory behavior strategies (Cole et al., 2004). Although the relation between emotion expression and regulation is complex, with even the most fine-grained analyses providing imperfect separation between expression and regulation, statistically controlling for children’s distress expressions may help parse out the unique effect of regulatory behaviors on parenting outcomes, with each providing effects independent of the other (Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, & Reiser, 2000; Eisenberg, Spinrad, Fabes, Reiser, Cumberland &, Shepard, 2004; Spinrad et al., 2007).

The effectiveness of regulation behaviors may vary by the specific emotional context. Research has asserted that mother-focused regulation and relying on mothers as a source of support are adaptive responses, particularly so during highly charged (or more subjectively threatening) emotional situations (Smith, Calkins, & Keane, 2006). Furthermore, Kopp (1989) points out that adaptive emotion regulation has long been considered in the specific context of how closely children meet their parents’ expectations for emotional expression. For example, parents might expect that toddlers rely on them during more stressful or seemingly threatening situations but be more self-sufficient during less stressful or less seemingly threatening situations, placing them in a unique developmental period relative to older children (Kopp, 1989). Thus, parents may prefer or at least tolerate toddlers’ use of more caregiver-focused regulation in high-threat situations while expecting more independent regulation in low-threat contexts. Given that, ultimately, toddlers are moving towards increasing independent regulation behaviors and decreasing dependent ones (Kopp, 1989), it is likely that caregiver-focused regulatory behaviors actually help the scaffolding process that results in more independent regulation at a later age (Diaz, Neal, & Amaya-Williams, 1990). Thus, certain emotion regulation behaviors may be more or less adaptive for particular children based on whether they fit maternal expectations, and this may depend on the context in which they are shown (although it should be acknowledged that there may be an underlying genetic component linking the match between both adaptive and maladaptive maternal expectations, on the one hand, and the reinforcement of behaviors in children on the other). In support of this, toddlers’ difficulties regulating fear in low-threat contexts, as opposed to solely in high-threat contexts, has been linked to their own physiological dysregulation and maladaptive outcomes (Buss, 2011; Buss et al., 2004), and parents have been shown to enact different levels of behavior in low versus high-threat contexts (Kiel & Buss, 2012). These pieces of evidence suggest that context is relevant to toddlers’ emotion regulation and affects parenting behaviors, although little is known about how context affects the predictive relation between toddlers’ emotion regulation and later parenting.

It is well established in the literature that parents affect the development of emotion regulation in children (Malatesta-Magai, 1989; Morris et al., 2007; Sroufe, 1996). However, it has not yet been determined how this emotion regulation behavior may, in turn, affect the parenting that children receive. Because it falls under the same larger domain of emotion processes, emotion socialization is a particularly relevant parenting outcome.

Emotion Socialization

Emotion socialization characterizes how parents express, model, discuss, and react to emotion with their children (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998). Maternal emotion socialization may be particularly relevant for very young children. Although older, school aged children may be more subject to peer influence (e.g., friends and classmates) and larger family contexts (e.g., siblings, relatives) (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), toddlers most directly learn from their parents’ reactions to emotion. Recently, parental responses to young children’s negative emotions have been a particular focus of research on emotion socialization (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000).

Emotion socialization has been conceptualized as involving both supportive and non-supportive responses to negative emotions such as fear, sadness, and anger (Eisenberg et al., 1998). According to Spinrad and colleagues (2007), supportive responses include problem-focused responses, emotion-focused responses, and expressive encouragement. Problem-focused responses involve helping children solve the problem which is causing them distress. Emotion-focused responses include comforting or distracting the child from the source of the distress. Expressive encouragement is the degree to which parents encourage the expression of negative emotion. Non-supportive responses, on the other hand, include minimization responses, or the devaluing or discounting of children’s negative emotions (e.g., saying, “get over it”), and punitive responses, which include verbal or physical punishment used to control children’s display of negative emotions (Fabes, Poulin, Eisenberg, & Madden-Derdich, 2002). Importantly, supportive and non-supportive responses are not opposites on a single spectrum. In a factor analysis performed by Spinrad and colleagues (2007), supportive and non-supportive responses loaded onto different factors, indicating that these responses are relatively independent.

Overall, the literature has found that parental responses to children’s negative emotions affect childhood emotional outcomes. Parental acceptance of emotion, greater frequency of emotion expression, and allowing children to have opportunities to express and learn about emotion may result in benefits such as early and later childhood social competence, constructive coping, and fewer behavioral problems (Denham & Grout, 1993; Eisenberg et al., 1996; Eisenberg et al., 2001, Eisenberg & Fabes, 1992; MacDonald & Parke, 1984; Saarni, 1990). Non-supportive responses ultimately lead to unhealthy emotional development by teaching young children to suppress emotional expressions and to use inappropriate emotion regulation strategies (e.g., avoidance, revenge-seeking), which may also promote the development of internalizing disorders, including child anxiety (Cicchetti, 1990; Eisenberg, Fabes, Carlo, & Karbon, 1992; Eisenberg et al., 1996; Hammen, Brennan, & Shih, 2004; Jones, Eisenberg, Fabes, & MacKinnon, 2002; Saarni, 1999; Shipman & Zeman, 2001). There has been very little research addressing the predictors of emotion socialization in general, but given the emerging evidence for a variety of child outcomes related to maternal emotion socialization, it is important to understand how mothers’ responses to negative emotions develop. Few studies have heeded the call by previous researchers to acknowledge and focus on child-driven effects on parenting. Pettit and Lollis (1997) and Pardini (2008) assert that researchers persist in considering children as passive recipients of the parenting they receive. Morris et al. (2007) also noted that while there is research focused on how socialization of emotion affects children, there is less research focused on how parents react to their children’s expressions of emotion. The current study will address this gap by examining 2-year-old toddlers’ emotion regulation behaviors as predictors of change in maternal emotion socialization from age 2 to age 3.

As mentioned, mothers of toddlers may begin to hold expectations for their young children’s emotional regulation, perhaps for more caregiver-focused regulation in more threatening situations and more independent regulation in minimally threatening situations (Kopp, 1989). Based on whether or not their toddlers’ regulatory behaviors conform to their expectations, mothers may respond differently to displays of negative emotion in the future. In low-threat situations, if toddlers conform to mothers’ expectations that they show more independent and less caregiver-focused regulation, mothers may respond to their toddlers’ future negative emotion with increased supportive and decreased non-supportive responses so as to encourage or sustain adaptive, independent emotion responses. Alternatively, for toddlers who do not conform to these expectations and use more caregiver-focused regulation, mothers must expend greater amounts of cognitive and emotional energy on soothing their children, which may decrease these supportive responses and increase mothers’ non-supportive responses.

When examining the predictive relation between toddlers’ emotion regulation and maternal emotion socialization, it is important to consider that regulatory behaviors may not predict maternal socialization in the same manner for all toddler-mother dyads. Therefore, the moderating influence of toddler gender is considered.

The Moderating Influence of Gender

Gender differences have been found in a variety of observed emotion processes (Brody, 1999; Buss, Brooker, & Leuty, 2008; Keenan & Shaw, 1997). A study by Buss, Brooker, and Leuty (2008) examined gender differences in toddler emotion regulation and found that girls were more likely to seek contact from and stay in closer proximity to their mothers compared to boys, even after controlling for distress. However, the association between distress and contact seeking or proximity was significant for boys but not for girls. Although it has been proposed that differences in expression may be a result of girls’ faster cognitive development, these differences may occur in part because parents discuss, express, or tolerate particular emotions in girls and boys to different degrees (Keenan & Shaw, 1997).

There are many examples in the literature of parents responding to emotion and behavior differently in girls and boys. Most generally, several studies have found that parents tend to openly discuss emotion overall more frequently around girls versus boys (Dunn, Bretherton, & Munn, 1987; Garner, Robertson, & Smith, 1997). It has also been found that parents are more tolerant of anger reactions in boys than in girls (Condrey & Ross, 1985). Mothers put more effort into their interactions and use higher levels of control to socialize difficult girls, whereas mothers of difficult boys tended to reduce the efforts in their interactions (Maccoby, Snow, & Jacklin, 1984; Smith et al., 2006). Furthermore, mothers respond to their boys more often with punishment in negative emotional situations (Smetana, 1989). In Simpson and Stevenson-Hinde (1985), parents responded differentially to shy boys versus shy girls. Shyness in girls was associated with more positive parenting behaviors, such as acceptance of the child, while shyness in boys was negatively associated with positive parenting behaviors and resulted in more parental worrying. This was consistent with the authors’ hypothesis that girls are encouraged to act according to sex-typed behaviors, including fearfulness, shyness, withdrawal, and compliance. Furthermore, it has been proposed that these different responses may occur because parents interpret behaviors differently for boys and girls (Keenan & Shaw, 1997). Not all studies have found meaningful gender differences in either child emotion regulation, expression, or parental responses to children’s emotions (Fivush, Brotman, Buckner, & Goodman, 2000; Fivush & Buckner, 2000; Lytton & Romney, 1991). Despite this, there is enough evidence to warrant the continued investigation of gender differences (Chaplin, Cole, & Zahn-Waxler, 2005). Specifically, because parents may respond differently to the exact same behavior in boys and girls, emotion regulatory behaviors might evoke different responses in mothers when displayed by boys versus girls. Understanding gender-specific developmental outcomes of emotion regulation may help tailor both theory and parenting interventions to individual children. Therefore, the current study hypothesized that gender may serve as a moderator of the relation between toddler emotion regulation and maternal emotion socialization.

Current Study

Overall, this study aimed to clarify the predictive relation between toddlers’ caregiver-focused and independent (i.e., self-soothing and attention-based) emotion regulatory behaviors, on the one hand, and maternal supportive and non-supportive socialization of emotion on the other, in the context of toddler gender. This study makes several contributions to the current literature. First, child-elicited effects on emotion socialization have not yet been explored. Another strength of the current study included controlling for age 2 emotion socialization in predicting age 3 outcomes. By doing so, we were able to assess change in emotion socialization over time. In addition, the current study examined the relation between emotion regulation and change in emotion socialization controlling for toddler distress occurring during observation of emotion regulation. We also considered the context (low versus high threat) in which toddlers’ emotion regulation occurs. Finally, we considered toddler gender as a condition under which there may be differences in relations between emotion regulatory behaviors and maternal emotion socialization responses. Therefore, several hypotheses are offered under the broader expectation that gender moderates the relation between toddlers’ emotion regulatory behaviors and maternal emotion socialization responses.

First, given recent evidence for behavior in low-threat contexts being especially salient to toddler and parenting outcomes (Buss, 2011; Buss et al., 2004; Kiel & Buss, 2012), it is hypothesized that emotion regulation will predict emotion socialization in low threat, but not high-threat contexts. More specifically, research suggests that mothers foster more independence in their boys by disengaging from them (Maccoby et al., 1984), which suggests a discouragement of caregiver-focused means of regulation. Therefore, in the low threat-contexts, it is hypothesized that boys’ higher levels of caregiver-focused regulation behaviors will predict lower levels of supportive socialization responses and more non-supportive responses from their mothers, while higher levels of independent regulation will predict more supportive socialization responses and lower levels of non-supportive responses. For girls, the literature offers less clear precedent for hypotheses. On the one hand, girls can express mild anxiety, dependency, and shyness that are considered normative by parents (Keenan & Shaw, 1997; Simpson & Stevenson-Hinde, 1985), so caregiver-responses may be preferred and independent strategies discouraged. Although discouragement of independent strategies of regulation may be in opposition to the idea that parents serve as a scaffold of regulation for young children with the goal that eventually children will regulate independently (Kopp, 1989), parents of toddlers are negotiating between caregiver-focused and independent regulation, so there may be periods or contexts in which parents do not want toddlers, particularly girls, to be completely independent. Early on in the scaffolding process, parents may want girls to use them as a source of regulation. On the other hand, girls show evidence of earlier cognitive and emotional maturity (Keenan & Shaw, 1997). This suggests that mothers might not be any more or less responsive to either type of strategy, resulting in no relation between their regulation strategies and emotion socialization responses in mothers. Therefore, we hypothesized that no predictive relations would exist for girls.

Method

Participants

A group of 117 mother-toddler dyads participated in the current study. Mothers were recruited through the mail based on birth announcements published in local newspapers and in person at meetings of the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program. The sample was reduced to those participants who completed all measures at the first assessment (n = 106). Toddlers (61 male and 45 female) were approximately 24-months-old (Mage = 24.74 mos., SDage = 0.71 mo.) at the time of the first assessment. Children were 84.9% European American, 4.7% African American, 8.5% Asian American, 1% biracial, and 1% “other.” Mothers in this sample tended to be college-educated (years of education: M = 16.40, SD = 2.45) with a range of 11 to 20 years of education. Mothers and children from the WIC program constituted 12.3% of the sample. Family gross income ranged from below $16,000 to higher than $61,000, with 40.7% of families making $60,000 or less. Mothers then completed a second questionnaire battery approximately 1 year after the age 2 assessment, with 11 mothers having been lost to attrition.

Procedure

Once a mother showed an interest in the study by mailing back a postcard or signing up at a WIC meeting, a laboratory staff member called the mother to arrange a laboratory visit and mailed her a packet with a consent form and a questionnaire packet including demographics and emotion socialization measures. At the laboratory, the experimenter told the mother that her toddler would be participating in a variety of activities (referred to as “episodes”), involving novel stimuli (i.e., a female clown, a puppet show, and a remote-controlled spider toy) modeled after the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB; Buss & Goldsmith, 2000; Goldsmith & Rothbart, 1996) and previous studies in the literature (Buss, 2011; Nachmias, Gunnar, Mangelsdorf, Parritz, & Buss, 1996).

Novelty episodes

For this study, toddler regulatory behaviors and overall level of distress were observed in three novelty episodes: interaction with a female clown, puppet show, and remote-controlled spider. Mothers were told to behave naturally or “as they typically would” for the duration of these episodes.

In the Clown episode, the toddler was invited to play a variety of games with a female research assistant dressed in a clown costume, complete with a wig and a nose. Games included blowing bubbles, playing catch with beach balls, and playing with musical instruments. Each game lasted approximately 1 minute, and then the clown asked the child to help her clean up the toys.

In the Puppet Show episode, the toddler was invited to watch and interact with lion and elephant puppets, which were controlled by the same research assistant from behind a small wooden stage. Toddlers were invited to play two games with the puppets; the first was to play catch with a small ball, and the second was a fishing game (1 min each). After the games, the toddler received a sticker from the puppets as a prize. The research assistant then appeared from behind the stage, showed the toddler the two puppets, and departed, leaving the puppets in the room for the toddler to examine until the primary experimenter returned.

In the Spider episode, the toddler interacted with a remote-controlled spider. The experimenter asked the mother to begin the episode with the toddler seated in her lap. A large plush spider, which was affixed to a remote-controlled truck hidden by a box lid, sat in the opposite corner of the room. The spider was controlled by remote from behind a one-way mirror. First, the spider approached halfway towards the toddler, paused for 10 seconds, and then retreated to its starting place in the corner. After another 10 seconds, it approached the toddler and mother the entire way, pausing for 10 seconds before it retreated back to the corner. The experimenter then re-entered the room and gave up to three friendly prompts for the toddler to touch the spider.

Measures

Emotion regulation

Toddler emotion regulation behaviors were coded by undergraduate and graduate level research assistants naïve to the hypotheses of the current study. Coders were trained by a master coder (omitted for blind review) for a minimum of 15–20 hours and were required to establish minimum reliability (kappa = .80) before coding independently. The master coder double-coded approximately 20% of cases to maintain reliability throughout coding. The coders and master coder reconciled discrepancies by watching episodes together and determining appropriate scores. Coding was conducted using the emotion regulation coding definitions provided in the Lab-TAB manual. Coders scored the presence versus absence of an array of toddlers’ behaviors that fit into broader categories of attention regulation, self-soothing, and caregiver-focused regulation established in previous studies (Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004; Grolnick, Bridges, & Connell, 1996; Rothbart & Bates, 1998) on a second-by-second basis. The percent agreement inter-rater reliabilities for attention regulation (98% agreement), self-soothing regulation (91% agreement), and caregiver-focused regulation (contact seeking, 100% agreement; looks to caregiver, 95% agreement) were all in the high range. Although there is precedent in the literature to consider both attention and self-soothing behaviors under the broader domain of independent regulation (Kopp, 1989), they are examined separately to determine unique influences. Attention-regulation behaviors included distraction (e.g., looking for several seconds at nothing in particular) and gaze aversion (e.g., brief glances away from the episode stimulus). Self-soothing behaviors included self-touching, or when a child inactively touched themselves (e.g. resting their hands on their lap), self-stimulation, when a child touched herself unconsciously and for soothing purposes (e.g. rubbing their hands, sucking their thumb), and fidgeting, when a child actively and/or nervously moved (e.g. waving their hands and/or limbs). Lastly, caregiver-focused behaviors were coded, such as looks to their caregiver and contact-seeking (e.g., running to or reaching for their caregivers). The current study used the frequency of attention-regulation and caregiver-focused behaviors (because these behaviors tend to occur for very short periods of time) and the duration of self-soothing behaviors (because these behaviors may continue for extended periods). To control for the slightly varying episode lengths among toddlers, proportions of regulatory behavior were created by dividing each toddler’s scores by the specific episode length. Furthermore, regulatory behaviors in the Clown and Puppet Show episodes were averaged to create low-threat regulation composites, while Spider episode regulatory behaviors were considered to be high-threat (see Buss, 2011 and Kiel & Buss, 2012 for previous studies validating these designations).

Emotion socialization

Emotion socialization was measured using the Coping with Toddlers’ Negative Emotion Scale (CTNES; Spinrad, Eisenberg, Kupfer, Gaertner, & Michalik, 2004), a toddler variant of the Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale that adjusted content to be more appropriate for toddlers versus preschool or school-aged children (Eisenberg et al., 1996; Fabes, Poulin, Eisenberg, & Madden-Derdich, 2002). The CTNES, administered at both age 2 and age 3, is a self-report measure with seven subscales that reflect how parents respond to their children’s negative emotions. Parents were asked how they would respond to their toddlers’ emotional expression in 12 hypothetical scenarios (e.g., “If my child becomes angry because he wants to play outside and cannot do so because he is sick, I would…”). Each situation was followed by seven responses, and parents rated the likelihood of responding on a scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely). Emotion-focused responses are strategies that are designed to help the child feel better, for instance in the above example, “I would: Soothe my child and/or do something with him to make him feel better.” Problem focused responses occur when parents help the child solve the problem that caused the child’s distress (e.g., “I would: Help my child find something he wants to do inside”). Expressive encouragement occurs when parents encourage children to express negative affect or validate children’s negative emotional states (e.g., “I would: Tell my child it’s ok to be angry”). Minimization responses capture how parents may devalue their children’s negative emotions (e.g., “I would: Tell my child that he is making a big deal out of nothing.”) Punitive responses capture how parents may punish or threaten their children for displaying negative emotions, for instance, “I would: Tell my child we will not get to do something else fun (i.e., watch T.V., play games) unless he stops behaving like that.” Following previously established guidelines resulting from a factor analysis by Spinrad et al. (2007), a “supportive responses” composite was created as the aggregate of emotion-focused responses, problem-focused responses, and expressive encouragement (36 items; αage2 = .83, αage3 = .87) whereas the “non-supportive responses” composite includes minimization responses, and punitive responses (24 items; αage2 = .87, αage3 = .72). The CTNES demonstrates good validity, with scores on the CTNES being related in expected ways to mothers’ attitudes about parenting, maternal responsivity, as well as the parents’ use of physical punishment. It also has acceptable test-retest reliability (rs =. 65 to .81) (Spinrad et al., 2004). The CTNES also shows good discriminant validity such that subscales capture parenting behaviors that are related to, yet distinct from broader based parenting measures (Fabes et al., 2001).

Distress

Overall toddler distress was coded observationally by episode and was included as a control variable in order to examine the effect of regulatory behaviors above and beyond children’s emotion expression. Coding of distress included all negative facial expressions (sadness, fear, etc.) and negative vocalizations such as crying, whimpering, and mothers’ comments about the child’s discomfort. One score on a 1 to 5 scale was provided for each toddler for each episode. A score of 1 indicated no distress shown, or a very fleeting display, neutral or other behavior; a score of 2 indicated one or two displays of low intensity distress; a score of 3 indicated any long displays of low intensity distress; a score of 4 indicated a few intense displays of distress, or consistent display of low intensity distress; and a score of 5 indicated a display of distress that lasted the whole episode, was very intense, or that the episode was stopped because of the child’s distress. Inter-rater reliability between coders and a master coder, assessed on approximately 20% of cases throughout coding, was found to be high (ICC = .91). Scores were averaged across the Clown and Puppet Show episodes for analyses concerning the low-threat episodes, and the score from Spider was used for the high-threat analyses.

Results

Missing Data

Independent samples t-tests on the106 dyads determined that mothers missing the age 3 assessment (n =11) did not significantly differ from those who completed the age 3 assessment in terms of demographic information or age 2 measures. Missing Value Analysis in SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, 2010) and Little’s MCAR test suggested that these data were consistent with the pattern of missing completely at random (χ2= 47.08, p > .05). Because listwise deletion has been found to bias results and reduce power of the analyses (Jeličić, Phelps, & Lerner, 2009; Widaman, 2006), missing Age 3 CTNES outcomes were imputed using multiple imputation (20 imputations), with emotion regulation strategies by episode, toddler gender, SES (as an auxiliary variable, although certainly, auxiliary variables are most beneficial when associated with patterns of missingness, which was not possible with MCAR missing data, Graham, 2009), age 2 values of CTNES scales, and existing values of age 3 CTNES used in the algorithm. We report pooled estimates of statistics, which represent weighted averages of statistics across the 20 imputations (i.e., each statistic’s contribution to the final estimate is weighted by its standard error).

Preliminary Analyses

Emotion regulation composites, age 2 and age 3 emotion socialization scales, and toddler distress were all found to have normal distributions (skew < 2.0). Descriptive statistics and gender t-tests for primary study variables are presented in Table 1. Girls were observed to have a significantly higher proportion of self-soothing regulation in the low threat contexts (M = 23.61, SD = 17.32) than boys (M = 17.56, SD = 13.60; Cohen’s d =.39). Girls also used a higher proportion of caregiver-focused regulation in the low threat context than boys (M = 2.95, SD = 1.56; M = 2.41, SD = 1.56; Cohen’s d =.34) at a marginal level (p < .10). Furthermore, girls demonstrated more distress than boys in the low threat context (p <. 05; M = 2.06, SD = 0.79; M = 1.79, SD = 0.65, respectively, Cohen’s d = .37) and marginally so (p < .10) in the high threat context (M = 3.18, SD = 1.05; M = 2.78, SD = 1.23, respectively, Cohen’s d = .34). There were no significant gender differences in age 2 or age 3 socialization scores. Paired samples t-tests revealed that toddlers demonstrated significantly less distress and fewer regulatory behaviors in the low-threat condition compared to the high-threat condition (six ts > 4.27, ps <.001).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Predictor, Moderator, and Outcome Variables

| Variable | Mean | SD | Gender t |

|---|---|---|---|

| LT Caregiver-focused regulation | 2.64 | 1.54 | −1.84† |

| LT Self-soothing regulation | 20.12 | 15.51 | −2.02* |

| LT Attention regulation | .83 | .77 | −.335 |

| HT Caregiver-focused regulation | 3.96 | 3.33 | −1.04 |

| HT Self-soothing regulation | 34.71 | 27.94 | −.242 |

| HT Attention regulation | 2.02 | 2.55 | .364 |

| LT Distress | 1.90 | .72 | −1.95* |

| HT Distress | 2.95 | 1.17 | −1.75† |

| Age 2 CTNES: Supportive | 5.58 | .77 | .660 |

| Age 2 CTNES: Non-Supportive | 2.56 | .78 | .648 |

| Age 3 CTNES: Supportive | 5.66 | .78 | 1.28 |

| Age 3 CTNES: Non-Supportive | 2.63 | .71 | 1.28 |

Note. N = 106. LT= low-threat. HT= high threat.t = independent samples t-test. Age 3 CTNES variable descriptives were obtained using an aggregate data set consisting of mean variables from 20 imputed data sets.

p< .10,

p< .05

Bivariate correlations are presented in Table 2. Low threat regulation strategies were positively correlated with distress in low-threat contexts. Only attention regulation in the high threat context positively related to distress in the high-threat context. Age 2 and age 3 supportive socialization, and age 2 and age 3 non-supportive socialization were positively associated.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations of Primary Variables

| Measure | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. LT caregiver-focused regulation | .14 | .09 | .34** | −.06 | .25* | .36** | .18† | .08 | −.05 | −.02 | −.21* |

| 2. LT self-soothing regulation | - | .20** | .07 | .07 | .01 | .34** | .06 | −.11 | −.08 | −.06 | −.14 |

| 3. LT attention regulation | - | −.01 | −.08 | .08 | .33** | .05 | .14 | .03 | .12 | −.05 | |

| 4. HT caregiver-focused regulation | - | .18† | .15 | .02 | .06 | .05 | .09 | −.08 | −.11 | ||

| 5. HT self soothing regulation | - | .18† | .02 | −.001 | −.08 | .05 | −.07 | .03 | |||

| 6. HT attention regulation | - | .04 | .25** | −.10 | .23* | −.10 | .14 | ||||

| 7. LT Distress | - | .33** | .11 | .12 | −.03 | −.03 | |||||

| 8. HT Distress | - | −.10 | .01 | −.12 | −.02 | ||||||

| 9. Age 2 CTNES: Supportive | - | −.14 | .68** | −.25* | |||||||

| 10. Age 2 CTNES: Non-Supportive | - | .04 | .70*** | ||||||||

| 11. Age 3 CTNES: Supportive | - | −.13 | |||||||||

| 12. Age 3 CTNES: Non-Supportive | - |

Note. N = 106. LT: low threat, HT: high threat

p < .10,

p< .05,

p< .01,

p<.001

Moderation Analyses

It was hypothesized that the relation between toddler emotion regulation behaviors and change in maternal socialization behaviors, controlling for distress, would depend on toddler gender. In a series of multiple regression models using the pooled estimates of the multiple imputations (which weight the contributions of each imputation’s estimate by its standard error), distress; caregiver-focused, self-soothing, and attention-focused regulation; gender; and the cross products between gender and each of the regulatory behaviors were entered as predictors of a particular emotion socialization strategy. Thus, each model contained all three regulatory behaviors and each of their interactions with toddler gender. Controlling for the age 2 measure suggests that models predicted change in emotion socialization. Power analyses suggested that with this number of predictors, regression models would be able to detect medium to large effect sizes (f2 values of .17 or above) with adequate power (> .80). Of note, the R2 values we observed in the following models were in the large range, which is consistent with effect sizes found in previous work examining emotion socialization and children’s emotional regulation and competence (Denham & Grout, 1993, Shipman & Zeman, 2001, Spinrad et al., 2007).

Models testing the outcome of each age 3 emotion socialization strategy, controlling for the respective age 2 emotion socialization strategy and toddler distress, were conducted separately for emotion regulation behaviors observed in low and high threat contexts. All moderation analyses described below follow guidelines set forth by Aiken and West (1991). Continuous variables were centered at their means prior to inclusion in models as main effects and creation of interaction terms. Toddler gender was dummy-coded (with boys initially coded as 0). Significant interactions found in any of the analyses were probed for simple effects by recoding the gender dummy variable and interpreting the mean-centered regulatory strategy simple effect for the appropriate gender. Given McClelland and Judd’s (1993) assertion that significant interaction effects are difficult to detect within non-experimental data, we chose to implement a Bonferroni correction at the level of simple effects to control for the two models tested within each emotional socialization outcome (p = .05/2 = .025).

Toddler gender was first examined as a moderator of age 2 emotion regulation in the high threat context predicting age 3 emotion socialization, controlling for age 2 socialization and toddler distress in a high threat context. As expected, there were no significant interactions or main effects in predicting age 3 supportive or non-supportive socialization responses in the high threat context (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of Regression Models Predicting Emotion Socialization with Gender as a Moderator

| Supportive LT non-supportive |

Non-Supportive HT non-supportive |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Threat | High Threat | Low Threat | High Threat | |||||||||

| F(9, 96)= 17.43*** | F(9, 94)= 16.91*** | F(9, 96)= 15.59*** | F(9, 94)=12.99*** | |||||||||

| R2=.620 | R2=.618 | R2= .594 | R2=.544 | |||||||||

| Variable | B | SE | t-test | B | SE | t-test | B | SE | t-test | B | SE | t-test |

| Age 2 CTNES scale | .793 | .133 | 5.98** | .773 | .118 | 6.54** | .587 | .105 | 5.60** | .607 | .109 | 5.58** |

| Distress | −.182 | .166 | −1.10 | −.044 | .071 | −.614 | −.024 | .145 | −.162 | −.008 | .066 | −.120 |

| Self-soothing regulation | −.001 | .008 | −.109 | −.004 | .003 | −1.28 | .005 | .007 | .693 | .002 | .003 | .497 |

| Caregiver-focused regulation | −.016 | .067 | −.237 | .002 | .036 | .059 | −.156 | .066 | −2.36* | −.049 | .044 | −1.13 |

| Attention regulation | .162 | .127 | 1.27 | .018 | .039 | .456 | −.097 | .126 | −.765 | .004 | .035 | .104 |

| Gender | −.127 | .154 | −.826 | −.141 | .155 | −.909 | −.068 | .147 | −.461 | −.092 | .150 | −.614 |

| Self-soothing regulation X gender | .003 | .011 | .239 | .000 | .006 | .022 | −.013 | .011 | −1.22 | −.007 | .006 | −1.05 |

| Caregiver-focused regulation X gender | .059 | .112 | .525 | −.024 | .053 | −.444 | .194 | .096 | 2.01* | .027 | .055 | .497 |

| Attention regulation X gender | −.103 | .205 | −.504 | −.005 | .066 | −.070 | .174 | .213 | .815 | −.021 | .069 | −.305 |

Note. N = 106. LT = low-threat. HT = high-threat. Coefficients, SEs, and t-tests were derived from pooled estimates of parameters (weighted by SEs) from 20 imputed data sets. ANOVA and R-squared statistics were estimated from an aggregated data set consisting of the mean of imputed data. Continuous predictors and covariates were centered at their means. Gender was dummy coded, with 0 = boys and 1 = girls.

p< .10,

p< .05,

p< .01,

p< .001

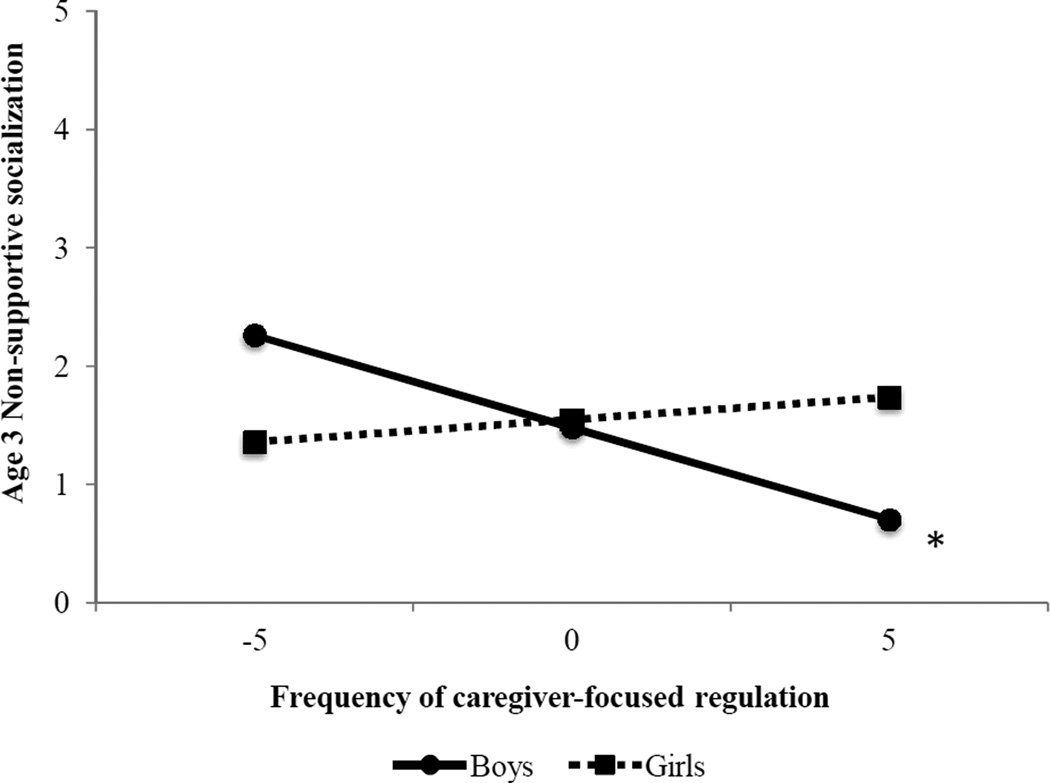

Toddler gender was then examined as a moderator of age 2 emotion regulation in the low threat context predicting age 3 emotion socialization, controlling for age 2 socialization and toddler distress. There were no significant interactions or main effects found to predict age 3 supportive socialization responses. A significant interaction between caregiver-focused regulation and gender was found in relation to non-supportive socialization (See Table 3). Specifically, as boys displayed a higher level of caregiver-focused regulation, they received fewer non-supportive socialization responses (b = −0.156, t (96) = −2.36, p = .02, SE = 0.066, 95% CI [−0.286, −0.025]). The effect was not significant for girls (b = 0.038, t (96) = 0.462, p = .645, SE = 0.082, 95% CI [−0.125, 0.201]) (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Probing of the significant interaction between caregiver-focused regulation and gender in relation to age 3 non-supportive socialization. Caregiver-focused regulation was centered at its mean. Gender was dummy coded to assist in probing (n = 106). Age 2 non-supportive socialization and toddler distress were included as covariates.

*p < .05

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to examine how toddler emotion regulation behaviors longitudinally predicted change in maternal emotion socialization, as moderated by toddler gender. Examining this relation contributes to the expanding knowledge of child-directed developmental effects, and when toddler characteristics play a role in these effects. The current study broadens the larger picture of emotional development by providing evidence for how toddlers elicit the parenting they receive. Analyses yielded longitudinal evidence for specific circumstances in which toddler gender moderated the predictive relation between age 2 toddler emotion regulation behavior and age 3 maternal emotion socialization, above and beyond toddler distress and controlling for age 2 emotion socialization. Although the current study did not explicitly explore potential bidirectional effects between emotion regulation and emotion socialization, it does provide evidence that child characteristics inform when toddlers may elicit parental socialization responses over time, suggesting the likelihood of transactional relations.

Consistent with hypotheses, no predictive relations emerged in the high-threat context. This is consistent with previous work demonstrating that individual differences in toddler behavior in these contexts may not be salient in relating to children’s future outcomes (Buss, 2011; Buss et al., 2004). The current study augments this growing area of research by showing that toddler emotion regulatory behavior in these contexts was also irrelevant in predicting parenting outcomes, specifically emotion socialization. We cannot speak to whether the strength of relations from analyses focusing on the high threat context were significantly less than those focusing on the low-threat context because context was not tested as a moderator. We encourage future research to address this issue.

Also consistent with hypotheses, gender was found to moderate the relation between emotion regulation behaviors in the low threat contexts and change in non-supportive socialization, but in an unexpected manner. When boys demonstrated higher levels of caregiver-focused regulation, they received decreased non-supportive socialization by age 3. Another way to conceptualize these results is that lower levels of caregiver-focused regulation at age 2 related to increased non-supportive socialization by age 3. These results have significant implications for boys because increased levels of non-supportive emotion socialization are linked to a variety of maladaptive child outcomes, including the development of internalizing problems (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1994; Eisenberg, Fabes, Carlo, & Karbon, 1992; Eisenberg et al., 1996; Gross & Levenson, 1993; Hammen, Brennan, & Shih, 2004; Shipman & Zeman, 2001). Interestingly, boys displayed fewer of all types of regulatory behaviors in the low-threat context than girls, yet these behaviors seem to have the greatest implication for them in eliciting non-supportive socialization. This could imply that boys have less freedom to make regulatory errors. It could also be the case that individual behaviors are less important for girls because they are using a broader range of regulatory strategies. These interpretations are in line with research by Buss and colleagues (2008), in which boys demonstrated significantly less caregiver-focused regulation relative to girls within a fear context. As a result, mothers may have less information or accuracy about boys’ emotional development relative to girls’ (Kiel & Buss, 2006), heightening the importance of what they do observe.

Perhaps boys between ages 2 and 3 may not be deemed to be “ready” by their mothers for solely using independent coping, and thus mothers prefer their boys to seek assistance from them to regulate their emotions. The current results provide more context for the main effects previously found in the literature. For instance, it has been found that boys receive more punishment in negative emotional situations (Smetana, 1989). The current study suggests that this may depend on boys’ specific regulatory strategies within a low-threat context. Mothers of boys may prefer to continue to see increased caregiver-focused regulation, and respond to less caregiver-focused regulation with increased non-supportive responses. Indeed, mothers’ behaviors in dyadic interactions do differ by child gender; there is also evidence to suggest that mothers respond more contingently to their boys’ expressions of emotion in infancy (Malatesta & Haviland, 1982) and toddlerhood (Buss et al., 2008). In an observational study by Radke-Yarrow and Kochanska (1990), mothers responded attentively to their toddler boys’ expressions of anger, but tended to ignore or attempt to inhibit their girls’ anger. Gender differences in maternal non-supportive responses to caregiver-focused regulation may be similar to findings of gender differences in other emotional competencies, such as emotion understanding, that develop within the parent-child relationship. For example, in Denham, Zoller, and Couchoud (1994), children with the lowest emotion understanding scores had mothers who showed more anger (which could be considered a punitive, non-supportive response). Interestingly,Eisenberg et al. (1998) suggested that mothers’ engagement and matching of emotional expressions in boys, assuming mothers’ desires to maintain positive affect, may be indicative of mothers’ perceptions that boys are more vulnerable to negativity and that they must counteract this with increased positive emotional interaction. Given the age of the toddlers in the current study, it is possible that mothers perceive their young boys to be more emotionally vulnerable than their young girls, which resulted in mothers’ increased non-supportive socialization responses as caregiver-focused regulation behaviors decreased in the low-threat context.

The current findings may also relate to previous literature on another type of emotion socialization, discussion of emotions. For instance, Brody (1993) found that mothers discussed positive emotions and emotional states more with their daughters than their sons, and focused on the causes and consequences of the child’s emotions moreso with their sons than their daughters. Brody (1993) posited that this was suggestive of mothers’ attunement to girls’ increased verbal abilities at young ages as compared to boys, which is consistent with findings that young girls may be more cognitively developed than boys (Keenan & Shaw, 1997). Gender differences in emotion discussion are similar to maternal emotion socialization results presented here, with mothers responding to boys with more punitive and minimizing responses when boys focused less on them to regulate their emotions. These effects could also indicate that mothers believe boys are less adept at soothing their own negative emotions. However, as Eisenberg, Cumberland, and Spinrad (1998) noted, more evidence is needed to determine if differences in verbal ability, sex-typed parental beliefs, or other variables are the cause of these differences in the Brody (1993) study and, thus, the gender differences in how emotion regulation predicts maternal supportive and non-supportive emotion socialization responses.

One recent, possible explanation for mothers’ preference of caregiver-focused regulation behaviors in boys within a low-threat context is that, as compared to previous generations, mothers currently recognize that boys need extra assistance in developing their emotional reactions and responses than girls do. In a qualitative study by Parker and colleagues (2012) examining parental emotional beliefs, it was found that across three ethnic groups, parents were concerned about teaching their boys how to express negative emotion without fear of consequences in order to allow them to be more emotionally open. Thus, mothers may have been increasingly responsive to boys’ emotion regulation strategies in low threat contexts in order to facilitate their boys’ positive emotional development.

There was no relation for any form of emotion regulation as it related to socialization outcomes over time in girls. Based on existing literature, mothers are more accepting of girls’ anxiety, and are less likely to encourage autonomy (Eggum et al., 2009; Nucci & Smetana, 1996; Pomerantz & Ruble, 1998). In this case, increased caregiver-focused regulation and decreased independent regulation would be expected to result in increased supportive and decreased non-supportive response, which was not the case here. These results seem to suggest that, compared to boys, girls are allowed a more flexible range of regulation strategies without changes in maternal socialization responses. This is not to say there are not additional variables that influence socialization outcomes for girls. One potential explanation centers on findings that suggest fathers’ parenting behaviors and responses affect girls more strongly than mothers’ behaviors do. For instance, Starrels (1994) found that fathers’ characteristics, such as education and parenting style, were related to supportive parenting outcomes only for daughters. Perhaps higher levels of caregiver-focused regulation behavior in girls, as it relates to increased supportive or decreased non-supportive socialization responses, are significant only when paternal emotion socialization responses are considered. The relation between child emotion regulation as it relates to changes in paternal emotion socialization could not be explored in the current study, but it is a promising direction for exploring both parent and child gender-specific effects.

There were no relations between either self-soothing or attention regulation and either supportive or non-supportive socialization responses for either boys or girls. However surprising, the specific development of socialization of effective self-soothing emotion regulation in young children has seldom been studied, so it is difficult to interpret this result in the context of the current literature. Literature stemming from the theory of Vygotsky suggests that the origins of broader self-regulation in childhood, including regulation of emotional processes, first come from adult-child interactions (Diaz, Neal, & Amaya-Williams, 1990). It can be further suggested that the success of effective self-regulation in toddlers is dependent on parent-child interactions. Since toddlers are less adept at self-soothing than older children, parent-child interactions should seek to reinforce the adaptive use of self-regulatory behaviors (Kopp, 1989). Assuming supportive socialization responses are adaptive, mothers should then encourage the use of increased self-soothing regulation with supportive responses. A lack of clear maternal supportive or non-supportive response to self-soothing regulation could be explained by toddlers being in a transition between mother-supported, scaffolded use of caregiver-focused strategies and self-soothing regulation. That is, mothers may vary in encouraging versus discouraging toddlers’ self-soothing in particular instances across both low and high threat contexts until they are deemed ready to soothe themselves (Kopp, 1989). Furthermore, contrary to hypotheses, there was no relation between toddlers’ attention regulation behaviors and maternal emotion socialization in either context, despite the fact that attention regulation’s relevance to future outcomes is a well-studied phenomenon (Eisenberg et al., 2000; Raffaelli, Crockett, & Shen, 2005). Perhaps these regulation behaviors are too subtle for parents to detect and respond to with toddlers, so they have little impact on emotion socialization outcomes.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of the current study provide insight into future directions of research. First, the community sample recruited for this study was composed mainly of European American mothers and toddlers. A valuable future direction would be to examine these relations in a more ethnically, racially, geographically, and clinically diverse sample. It could be that different cultural groups present different frequencies of emotion regulation strategies and socialization responses, and different relations between them, much like reactivity and emotional expressivity have been found to differ (Saarni, 1999). For example, Raval and Martini (2009) found that collectivism, religion, and social organization affected Gujarati mothers’ acceptance of their children’s emotions. Cultural differences in gender role constructs and therefore maternal expectations for boys and girls may also shape the moderating effect of gender. Our results primarily inform what is occurring in normative development, but an important area for future inquiry is whether or not these results are indicative of toddlers’ emotional dysregulation and future risk of psychopathology. Although the current study is unable to address maternal cognitions that may be driving socialization responses to toddlers’ regulatory behaviors, future research could investigate how explicit or implicit measures of maternal gender expectations moderate the relation between emotion regulation and emotion socialization over time. Assessing maternal cognitions could also address whether a “match” between maternal expectations and child behaviors is linked to known adaptive and maladaptive child outcomes.

Given reported differences between observed and parent-reported measures of child behaviors and temperament (Rothbart & Bates, 1998), there are likely to be differences in associations between toddlers’ behaviors and mothers’ behaviors depending on the modality of measurement as well. For example, results may differ when emotion socialization is measured in the laboratory as a direct response to toddlers’ regulatory behaviors, although this has not been studied explicitly. Relatedly, the complexity of parsing out children’s distress or emotion expression from regulatory behaviors may not be ideally acknowledged by controlling for a global rating of distress within each of the high and low-threat contexts. One solution may be to change the level of analysis, for example by using event-triggered sampling, or multiple, observed responses to novelty within an episode in order to directly measure toddler’s behavior in relation to specific expressions or changes in situational demands. Whether or not this approach shows marked improvement over other methods may depend on the density of the regulatory and expressive behaviors within a sample (Buss & Goldsmith, 1998). Furthermore, future work conducted with a larger sample size that explicitly tests a three-way interaction among context, gender, and regulation would elaborate upon our findings.

Although the current study does not explicitly examine the bidirectional relation between child emotion regulation and maternal emotion socialization, it provides needed evidence for the role of child-driven effects in a literature strong in documenting the effects of parent characteristics and practices on child outcomes. Future studies should incorporate this new perspective by providing a true test of bidirectional effects, and comparing the strength of parent-driven and child-driven effects.

Conclusion

The current study examines when, under the condition of toddler gender, toddler emotion regulation predicts emotion socialization. Gender was found to moderate the relation between caregiver-focused regulation in a low-threat context and non-supportive socialization, with boys’ increased caregiver-focused regulation resulting in decreased non-supportive socialization. Results intriguingly suggest that children’s regulation strategies and gender elicit the parenting they receive.

Acknowledgments

The project from which these data were derived was supported, in part, by a National Research Service Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (F31 MH077385-01) and a University of Missouri Department of Psychological Sciences Dissertation Grant granted to Elizabeth Kiel, and a grant to Kristin Buss from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH075750). We express our appreciation to the families and toddlers who participated in this project.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Wittig BA. Attachment and the exploratory behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. In: Foss BM, editor. Determinants of infant behavior. Vol. 4. London: Methuen; 1969. pp. 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR. On understanding gender differences in the expression of emotion. Human Feelings: Explorations in Affect Development and Meaning. 1993:87. [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR. Gender, emotion, and the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH, Goldsmith HH. Context-specific freezing and associated physiological reactivity as a dysregulated fear response. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40(4):583. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA. Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Context, fear regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(3):804–819. doi: 10.1037/a0023227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Brooker RJ, Leuty M. Girls most of the time, boys some of the time: Gender differences in toddlers' use of maternal proximity and comfort seeking. Infancy. 2008;13(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Goldsmith HH. Fear and anger regulation in infancy: Effects on the temporal dynamics of affective expression. Child Development. 1998;69(2):359–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Goldsmith HH. Manual and normative data for the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery - Toddler Version. (Psychology Department Technical Report) Madison: University of Wisconsin; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C. Parental socialization of emotion expression: Gender differences and relations to child adjustment. Emotion. 2005;5(1):80–88. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. The organization and coherence of socioemotional, cognitive, and representational development: Illustrations through a developmental psychopathology perspective on Down’s syndrome and child maltreatment. In: Thompson R, editor. Socioemotional development: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation 1988. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1990. pp. 259–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and direction for child development research. Child Development. 2004;75(2):317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condrey JC, Ross DF. Sex and aggression: The influence of gender label on the perception of aggression in children. Child Development. 1985;51:943–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Grout L. Socialization of emotion: Pathways to preschoolers’ emotional and social competence. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 1993;17:205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Zoller D, Couchoud EA. Socialization of preschoolers' emotion understanding. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30(6):928. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Neal CJ, Amaya-Williams M. The social origins of self-regulation. In: Moll LC, editor. Vygotsky and education: Instructional implications and applications of sociohistorical psychology. 1990. pp. 127–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Bretherton L, Munn P. Conversations about feeling states between mothers and their children. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Eggum ND, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Reiser M, Gaertner BM, Sallquist J, Smith CL. Development of shyness: Relations with children's fearfulness sex, maternal behavior. Infancy. 2009;14(3):325–345. doi: 10.1080/15250000902839971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Emotion, regulation, and the development of social competence. In: Clark MS, editor. Review of personality and social psychology: Emotion and social behavior. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 119–150. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Carlo G, Karbon M. Emotional responsivity to others: Behavioral correlates and socialization antecedents. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1992;55:57. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219925506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Reiser M. Dispositional emotionality and regulation: their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2000;78(1):136. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC. Parents' reactions to children's negative emotions: Relations to children's social competence and comforting behavior. Child Development. 1996;67(5):2227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Murphy BC, Guthrie IK, Jones S, Friedman J, Poulin R, Maszk P. Contemporaneous and longitudinal prediction of children's social functioning from regulation and emotionality. Child Development. 1997;68(4):642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Gershoff ET, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Cumberland AJ, Losoya SH. Mothers’ emotional expressivity and children’s behavior problems and social competence: Mediation through children’s regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:475–490. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Cumberland A, Shepard SA, et al. The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s resiliency and adjustment. Child Development. 2004;75:25–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Morris AS. Regulation, resiliency, and quality of social functioning. Self and Identity. 2002;1(2):121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Poulin RE, Eisenberg N, Madden-Derdich DA. The coping with children’s negative emotions scale (CCNES): Psychometric properties and relations with children’s emotional competence. Marriage and Family Review. 2002;34(3–4):285–310. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Brotman M, Buckner JP, Goodman S. Gender differences in parent–child emotion narratives. Sex Roles. 2000;42(3/4):233. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Buckner J. Gender, sadness and depression: The development of emotional focus through gendered discourse. In: Fischer AH, editor. Gender and emotion: Social psychological perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 232–253. [Google Scholar]

- Garner PW, Robertson S, Smith G. Preschool children's emotional expressions with peers: The roles of gender and emotion socialization. Sex Roles. 1997;36(11/12):675. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Rothbart MK. Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (LAB-TAB). Pre- and Locomotor Versions. University of Oregon; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS, Bridges LJ, Connell JP. Emotion regulation in two-year-olds: Strategies and emotional expression in four contexts. Child Development. 1996;67(3):928–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64(6):970. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.6.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA, Shih JH. Family discord and stress predictors of depression and other disorders in adolescent children of depressed and nondepressed women. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):994. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127588.57468.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeličić H, Phelps E, Lerner RM. Use of missing data methods in longitudinal studies: The persistence of bad practices in developmental psychology. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1195–1199. doi: 10.1037/a0015665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, MacKinnon DP. Parents' reactions to elementary school children's negative emotions: Relations to social and emotional functioning at school. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2002;48(2) [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Shaw D. Developmental and social influences on young girls' early problem behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121(1):95–113. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Buss KA. Associations among context-specific maternal protective behavior, toddlers' fearful temperament, and maternal accuracy and goals. Social Development. 2012;21(4):742–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:343–354. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):561. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H, Romney DM. Parents' differential socialization of boys and girls: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109:267–296. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, Snow ME, Jacklin CN. Children's dispositions and mother-child interaction at 12 and 18 months: A short term longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:459–472. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald K, Parke RD. Bridging the gap: Parent-child play interaction and peer interactive competence. Child Development. 1984;55(4):1265–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malatesta-Magai C. The role of emotions in the development and organization of personality. In: Thompson R, editor. Nebraska symposium: Socioemotional development. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press; 1989. pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Malatesta CZ, Haviland JM. Learning display rules: The socialization of emotion expression in infancy. Child Development. 1982:991–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf SC, Shapiro JR, Marzolf D. Developmental and temperamental differences in emotion regulation in infancy. Child Development. 1995;66(6):1817–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GH, Judd CM. Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114(2):376. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:361–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias M, Gunnar M, Mangelsdorf S, Parritz RH, Buss KA. Behavioral inhibition and stress reactivity: The moderating role of attachment security. Child Development. 1996;67(2):508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nucci L, Smetana JG. Mothers' concepts of young children's areas of personal freedom. Child Development. 1996;67(4):1870–1886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA. Novel insights into longstanding theories of bidirectional parent–child influences: Introduction to the special section. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(5):627–631. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9231-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AE, Halberstadt AG, Dunsmore JC, Townley G, Bryant A, Jr, Thompson JA, Beale KS. “Emotions are a window into one's heart”: A qualitative analysis of parental beliefs about children's emotions across three ethnic groups. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2012;77(3):1–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2012.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Lollis S. Introduction to special issue: Reciprocity and bidirectionality in parent–child relationships: New approaches to the study of enduring issues. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1997;14:435–440. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz EM, Ruble DN. The Role of Maternal Control in the Development of Sex Differences in Child Self-Evaluative Factors. Child Development. 1998;69(2):458–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke-Yarrow M, Kochanska G. Anger in young children. Psychological and biological approaches to emotion. 1990:297–310. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Crockett LJ, Shen YL. Developmental stability and change in self-regulation from childhood to adolescence. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2005;166(1):54–76. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.166.1.54-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raval VV, Martini TS. Maternal socialization of children's anger, sadness, and physical pain in two communities in Gujarat, India. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33(3):215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Eisenberg N, editor; Damon W, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3 Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 105–176. (Series Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Derryberry D. Development of individual differences in temperament. In: Lamb ME, Brown AL, editors. Advances in developmental psychology. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1981. pp. 37–86. [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. Emotional competence: How emotions and relationships become integrated. Socioemotional development. In: Thompson R, editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Vol. 36. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1990. pp. 115–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarni C. The development of emotional competence. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shipman KL, Zeman J. Socialization of children's emotion regulation in mother–child dyads: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(2):317. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescents' emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Development. 2003;74(6):1869. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson AE, Stevenson-Hinde J. Temperamental characteristics of three- to four-year-old boys and girls and child-family interactions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1985;26(1):43–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1985.tb01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Toddlers' social interactions in the context of moral and conventional transgressions in the home. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25(4):499. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, Calkins SD, Keane SP. The relation of maternal behavior and attachment security to toddlers' emotions and emotion regulation. Research in Human Development. 2006;3(1):21. [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad T, Eisenberg N, Kupfer A, Gaertner B, Michalik N. The coping with negative emotions scale; Paper presented at the International Conference for Infant Studies; 2004, May; Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Gaertner B, Popp T, Smith CL, Kupfer A, Greving K, Liew J, Hofer C. Relations of maternal socialization and toddlers’ effortful control to children’s adjustment and social competence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(5):1170–1186. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS for Windows 19.0 [Computer software] Chicago, IL: IBM Corporation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Emotional development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Starrels ME. Gender differences in parent-child relations. Journal of Family Issues. 1994;15(1):148–165. [Google Scholar]

- Walden T, Lemerise E, Smith MC. Friendship and popularity in preschool classrooms. Early Education. 1999;10(3):351. [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF. Missing data: What to do with or without them. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2006;71(3):42–64. [Google Scholar]