Abstract

Objective

To examine changes in depressive symptoms and treatment in the first three years following bariatric surgery.

Design and Methods

The Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2 is an observational cohort study of adults (n=2,458) who underwent a bariatric surgical procedure at one of ten US hospitals between 2006–9. This study includes 2,148 participants who completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) at baseline and ≥ one follow-up visit in years 1–3.

Results

At baseline, 40.4% self-reported treatment for depression. At least mild depressive symptoms (BDI score≥10) were reported by 28.3%; moderate (BDI score 19–29) and severe (BDI score ≥30) symptoms were uncommon (4.2% and 0.5%, respectively). Mild-to-severe depressive symptoms independently increased the odds (OR=1.75; p=.03) of a major adverse event within 30 days of surgery. Compared with baseline, symptom severity was significantly lower at all follow-up time points (e.g., mild-to-severe symptomatology was 8.9%, 6 months; 8.4%, 1yr; 12.2%, 2yrs; 15.6%, 3yrs; ps<.001), but increased between 1 and 3 years postoperatively (p<.01). Change in depressive symptoms was significantly related to change in body mass index (r=.42; p<0001).

Conclusion

Bariatric surgery has a positive impact on depressive features. However, data suggest some deterioration in improvement after the first postoperative year.

Keywords: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, severe obesity, weight loss, treatment, depression, antidepressant medication

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is now regarded as the most effective treatment to achieve and maintain a large and sustained weight loss in severely obese adults (1). Utilization of such procedures has escalated in recent years (2). Nevertheless, outcomes of bariatric surgery are variable and research is needed to identify predictors of outcome (3).

Depressive symptoms and mood disorders are commonly seen among severely obese adults. Data from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study demonstrated that depressive symptomatology was elevated relative to population data among both the obese sample electing bariatric surgery and conventionally treated matched controls (4). However, depressive symptomatology was significantly higher among those electing surgery (5). Studies using the Hamilton Depression Scale (HDS) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) have also shown elevated depression symptoms in bariatric surgery candidates (6,7,8). Additionally, it has been reported that antidepressants are the most frequently prescribed type of medication in this population (9), and are frequently continued after surgery (9, 10, 11).

An early report (12) found that depression prior to bariatric surgery was associated with a higher rate of medical complications in the post-surgery period. However, this study was conducted in a small sample (n=40) of patients who had undergone vertical-banded gastroplasty, a procedure rarely employed today.

The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) have accounted for the majority of bariatric surgical procedures performed in the United States over the last decade. Studies comparing pre- to post-operative rates of depressive symptoms and affective disorders following RYGB and LAGB have generally found decreases in both the severity of the symptoms (13, 14,15) and in the rate of mood disorder diagnoses (16,17,18). However, only a few studies have included follow-up beyond the first postoperative year, and most have been limited to small samples (15,18,19,20). An exception is the SOS (n=655), which found significant improvements in depressive symptoms 10 years following RYGB, fixed or laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, or vertical-banded gastroplasty, the modal procedure utilized (21).

Utilizing data from the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2, a large cohort study of adults who have undergone a bariatric surgical procedure at one of ten participating US hospitals, the aims of the current analysis are: 1) to determine whether baseline depressive symptoms and anti-depressant medication use predict short-term 30-day) major adverse outcomes; 2) to describe changes in depressive symptoms and treatment for depression during the first three years following surgery; 3) to determine if changes differ by surgical procedure (RYGB vs. LAGB); and 4) to examine whether depressive symptomatology changes in parallel with body mass index (BMI).

Methods

The Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2 (LABS-2) study is designed to assess the risks and benefits of bariatric surgery (22,23,24). Patients at least 18 years old seeking their first bariatric surgery procedure (RYGB, LAGB, sleeve gastrectomy, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, or banded gastric bypass) as part of clinical care by a LABS-certified surgeon at one of the ten participating hospitals throughout the United States were recruited between February of 2006 and February of 2009, resulting in a cohort of 2,458 patients. All participants provided an institutional review board approved consent. The study, #NCT00465829, is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Data collection and baseline health status for the LABS-2 cohort have been published (23,24). Measures were collected independently of surgical care, and prior to completing psychiatric questionnaires patients were informed that their responses would not impact their acceptance for surgery. Participants returned for a brief 6 month and then broader annual assessments. The analysis sample for this paper included 2,146 of 2,458 (87.3%) LABS-2 participants whose depressive symptoms were assessed at baseline and at least one follow-up visit within the first three years following surgery (1782 at 6 months, 1698 at 1 year, 1451 at 2 years and 1411 at 3 years).

Outcome Measures

Depressive Symptoms

Symptoms of depression over the past week were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory, version 1 (BDI-1) (25,26). Because many patients are advised to lose weight in preparation for surgery, no points were assigned to the BDI item, “I have lost more than 5 pounds,” for participants who indicated purposefully trying to lose weight. The following cut-offs were used for the total score: 0–9, 10–18, 19–29 and 30–63, reflecting no/minimal, mild, moderate and severe symptomatology, respectively.

Antidepressant Medication

Using a study-specific medication form (23) participants recorded the names and frequency of use of all prescribed medications taken within the past 90 days. Current antidepressant medication use was defined as taking a medication classified as an antidepressant, at least daily, because the reasons for taking medications were not determined.

Hospitalizations and Counseling for Depression

At baseline and annual follow-ups, participants self-reported a history of treatment for psychiatric or emotional problems, including hospital admissions and counseling with a mental health professional, and reason(s) for treatment. When bipolar disorder was indicated, it was not classified as “depression.”

Treatment for Depression

Participants were categorized as having recently received treatment for depression if they were currently taking an antidepressant medication or had attended counseling for depression in the past 12 months.

Short-term Adverse Surgical Outcomes

Adverse outcomes of surgery were assessed via medical records and participant interview 30 or more days following surgery. If any of the following occurred within 30 days after surgery the patient was considered to have had a major short-term adverse outcome: death; deep-vein thrombosis or venous thromboembolism; reintervention using percutaneous, endoscopic, or operative techniques; or failure to be discharged from the hospital within 30 days after surgery, termed the “composite endpoint”(10).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.3), R (version 3.0.0) and Mplus (version 7). All reported P values are two-sided; P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Baseline characteristics of LABS-2 participants in the analysis versus those who were excluded due to missing BDI data were compared with Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables.

Missing data were assumed to be missing at random (MAR) (27). Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) were used to evaluate baseline depressive symptoms and anti-depressant medication use, and specifically use of SRIs, as predictors of major short-term adverse outcome (i.e., the “composite endpoint”). Correlation among patients of the same surgeon was accounted for by including different random intercepts for sites and for surgeons within site. Factors that were independently related to the composite endpoint in previous work (i.e., surgical procedure, BMI, a history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolus, obstructive sleep apnea, and severe walking limitation) (22) were considered as covariates. Using backward elimination, only covariates that were independently significantly related to the outcome in this sample were retained. Predicted probabilities of having a major short-term adverse outcome were calculated based on the multivariable model.

Linear mixed models (LMM) were used to evaluate baseline depressive symptoms as a predictor of post-operative depressive symptoms. LMM and GLMM were also used to test whether depressive symptoms, hospitalizations for depression, and treatment for depression, changed over time. An interaction with time was considered in all models. Mixed-effects ordinal logistic regression models were used to determine the odds of depressive symptom severity changing over time. To compare more to less severe symptoms, the outcome was dichotomized in three ways (minimal-to-moderate symptoms vs. severe, minimal-to-mild symptoms vs. moderate-to-severe, and minimal symptoms vs. mild-to-severe symptoms). For all models, first each follow-up time point was compared to baseline; second, each follow-up time point was compared to the previous follow-up time point. To determine whether change in depression-related parameters differed by surgical procedure, GLMMs were run among those who underwent the two most common procedures, RYGB and LAGB, with a procedure indicator variable. Latent Growth Modeling (LGM) was used to examine the correspondence between changes in BMI with parallel change in BDI score trajectory in the entire sample and among only those with baseline mild-severe depressive symptoms.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the analysis sample are shown in Table 1. Compared to those who were excluded from analysis (n=312), those in the analysis (n=2, 146) had a higher household income (p=.03). There were no significant differences (ps>.05) between groups with respect to sex, age, race, ethnicity, marital status, employment status and BMI. Additionally, baseline depressive symptom severity or treatment for depression did not significantly differ between the analysis sample, and those who were excluded, but were not missing these data (n=206 for depressive symptom severity and n=246 for treatment for depression of the 312 excluded from analysis).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of those included and excluded from the main analysis

| Included (N=2146a) | Excluded (N=312a) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 461(21.5) | 66(21.2) | 0.90 |

| Age (years), median (IQR), [range] | 46(37,54) | 44(36,54) | 0.29 |

| [18–76] | [20–78] | ||

| Race | 0.21 | ||

| White | 1845(86.6) | 257(82.9) | |

| Black | 216(10.1) | 40(12.9) | |

| Other | 69(3.2) | 13(4.2) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 103(4.8) | 16(5.1) | 0.80 |

| Married or living as married | 1300(64.4) | 144(59.0) | 0.10 |

| Employed for pay | 1397(63.4) | 154(69.3) | 0.06 |

| Household income | 0.03 | ||

| <$25,000 | 343(17.4) | 59(25.0) | |

| $25,000–$49,000 | 515(26.2) | 53(22.5) | |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 462(23.5) | 60(25.4) | |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 319(16.2) | 34(14.4) | |

| ≥$100,000 | 329(16.7) | 30(12.7) | |

| Education | 0.08 | ||

| ≤High school | 454(22.5) | 67(27.3) | |

| Some college | 815(40.4) | 103(42.0) | |

| ≥ College degree | 750(37.1) | 75(30.6) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR), [range] | 45.9(41.8,51.4) | 45.8(41.5,52.6) | 0.57 |

| [33.0–94.3] | [34.8–77.2] | ||

| Surgical Procedure | 0.29 | ||

| Roux–en–Y gastric bypass | 1507(70.2) | 231(74.0) | |

| Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band | 539(25.1) | 71(22.8) | |

| Other proceduresb | 100(4.7) | 10(3.2) |

Values are expressed as no. (%) unless otherwise indicated. The number of participants across categories may not sum to the total number of participants due to missing data.

Sleeve gastrectomy, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, or banded gastric bypass.

Baseline Depressive Symptoms and Major Short-term Adverse Outcomes

Baseline BDI score (entered as a continuous variable) was not significantly related to likelihood of a major adverse event within 30 days of surgery (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.03 per BDI point; 95% CI=0.99–1.07; p=.18), whereas antidepressant medication use was (AOR=1.76; 95% CI=1.02–3.04; p=.04), controlling for significant covariates, surgical procedure (p<.01) and BMI (p=.03), as well as site and surgeon. However, having mild-severe depressive symptoms (BDI ≥10), compared to no or minimal symptoms (BDI<10) and taking antidepressant medication daily were both independently related to a higher odds of a major adverse event within 30 days (AOR=1.77; 95% CI=1.03–3.05; p=.04, and AOR=1.72; 95% CI=1.002–2.96; p=.04, respectively). Given the rarity of moderate (6.0%) and severe (0.9%) depressive symptomatology at baseline and the 30-day composite endpoint (3.1%), we were underpowered to test whether likelihood of a major short-term adverse event differed by severity of symptoms among those with BDI scores ≥ 10 or whether there was an interaction between depressive symptom groups (no/minimal vs. mild-severe) and surgical procedure. When analysis was limited to RYGB procedures, antidepressant medication use was no longer statistically significant (AOR=1.51; 95% CI=0.86–2.65; p=.15), whereas the odds associated with depressive symptoms was higher (AOR=2.13; 95% CI=1.22–3.75; p<.01). A model limited to LAGB (n=538) would not converge, as only four participants who had a LAGB had a major adverse outcome and all had no/minimal depressive symptoms.

Exploratory analysis was conducted to examine the relation between depressive symptoms and components of the composite endpoint. Death (n=0), DVT/PE (n=5) and failure to be discharged (n=4) were too rare to model. Sixty-three of 67 participants with the composite endpoint had at least one re-intervention, most commonly a reoperation (n= 47). Because of the known association between SRI usage and bleeding, we posited that perhaps a bleeding diathesis was involved (28). After controlling for site, surgeon, surgical procedure and BMI, those with baseline mild-severe depressive symptoms had a 2.52 higher odds of a reoperation (95% CI=1.29–4.91; p<.01), within 30 days of surgery, whereas antidepressant medication use, or specifically SRI use, was not statistically significant (AOR=1.86; 95% CI=0.95–3.67; p=.07, AOR=1.41; 95% CI=0.72–2.75; p=.31, respectively). Because only 6 participants (0.3%) had postoperative events attributed to bleeding we were underpowered to examine risk factors.

Baseline Depressive Symptoms and Post-operative Depressive Symptoms

Compared to those with no or minimal symptoms, those with depressive symptoms at baseline had a 6.77 higher odds (95% CI=5.47–8.38; p<.0001) of at least mild depressive symptoms at follow-up. Those with moderate-severe depressive symptoms at baseline had a 7.80 higher odds (95% CI= 5.26–11.58; p<.0001) of moderate-severe depressive symptoms at follow-up.

Table 2 shows BDI score, depressive symptom severity groups, hospitalizations for depression, and treatment for depression by time point. Data attainment for these outcomes was similar to the BDI (as reported in methods). There was a significant change in BDI score from baseline to each follow-up visit (p<.0001); the decrease in BDI score was greatest at the 1 year follow-up (mean=−3.6). Mean change in BDI score between 6 months and 1 year (mean=−0.2; p=.06) was not significant. Changes in scores between 1 and 2 years (mean=0.7; p<.0001) and 2 and 3 years (mean=0.5; p<.001), were significant.

TABLE 2.

Depressive symptoms, hospitalization for depression and treatment for depression by time point, based on mixed models a

| Baseline | Follow-up Visit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 monthsb | 1 year | 2 years | 3 years | ||

| BDI score, mean (95%CI) | 7.7(7.4–7.9) | 4.3(4.1–4.6) | 4.1(3.8–4.3) | 4.7(4.4–5.0) | 5.3(5.0–5.6) |

| Depressive symptom severity, %(SE) | |||||

| Minimal | 71.7(1.2) | 91.1(0.7) | 91.6(0.7) | 87.8(0.9) | 84.4(1.1) |

| Mild | 23.6(0.8) | 7.7(0.4) | 7.2(0.4) | 10.5(0.5) | 13.3(0.6) |

| Moderate | 4.2(0.2) | 1.1(0.1) | 1.0(0.1) | 1.5(0.1) | 2.0(0.1) |

| Severe | 0.5(0.08) | 0.1(0.02) | 0.1(0.02) | 0.2(0.03) | 0.2(0.04) |

| Hospitalization for depression, %(SE) | 0.9(0.2) | NA | 0.9(0.2) | 1.1(0.3) | 1.7(0.3) |

| Treatment for depressionc, %(SE) | 40.4(1.7) | NA | 32.0(1.7) | 33.1(1.8) | 34.6(1.9) |

| Antidepressant medication use, %(SE) | 35.3(1.8) | 24.0(1.5) | 26.7(1.7) | 27.6(1.8) | 27.5(1.8) |

| Counseling for depression, %(SE) | 14.6(0.9) | NA | 9.1(0.8) | 10.1(0.9) | 10.4(0.9) |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, CI: Confidence Interval, SE=Standard Error.

Results are based on models using all available data: depressive symptoms, n=2146; hospitalization for depression, n=2116; antidepressant medication, n=2143; counseling for depression, n=2115; and treatment for depression, n=2103.

Hospitalization and counseling for depression were not assessed at the six-month visit.

Antidepressant medication use and/or counseling.

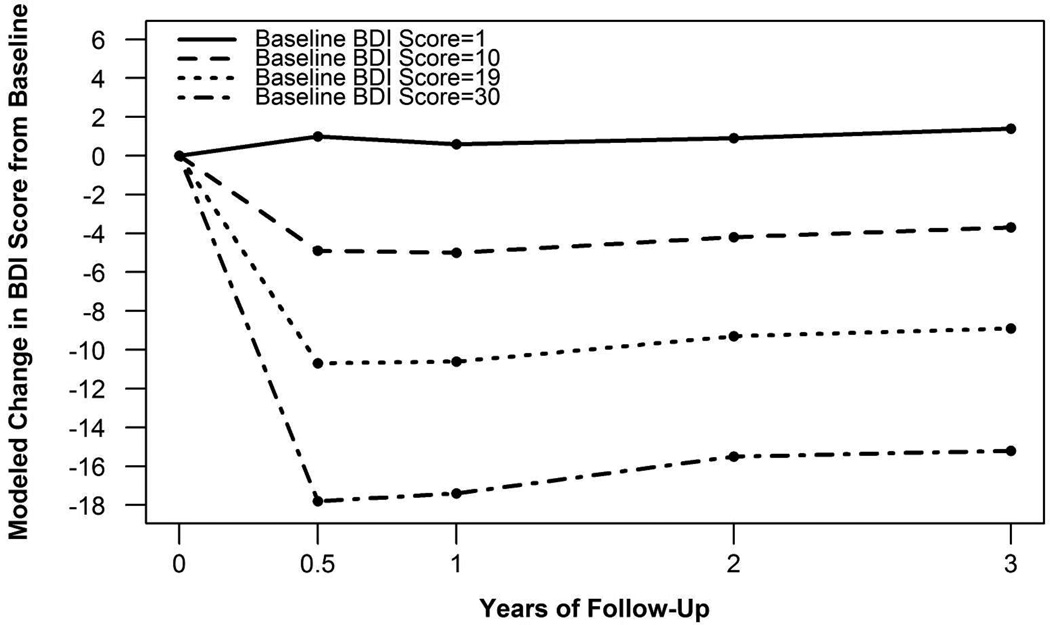

Change in BDI score following surgery was significantly related to baseline BDI score (p<.0001). Specifically, those with a higher baseline BDI score had a larger change in BDI score following surgery compared to those with a lower baseline score (Figure 1). A significant interaction between baseline BDI score and time (p<.01) indicated baseline BDI score had a larger effect at earlier follow-up time points compared to later follow-up time points.

Figure 1. Modeled change in BDI score from baseline by baseline BDI scorea.

aChange in BDI score following surgery was significantly related to baseline BDI score (p<.0001). A significant interaction between baseline BDI score and time (p<.01) indicated baseline BDI score had a larger effect at earlier compared to later follow-up time points. An example from each of the four depressive symptom severity groups is provided.

The distribution of depressive symptom severity by time point is also shown in Table 2. There was a significant change in severity of depressive symptoms from baseline to each follow-up visit (p=<.0001). Compared to baseline, participants had an odds ratio of 3.04, 3.33, 1.83, and 1.13 of having less severe depressive symptoms at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 3 years, respectively (p=<.0001). There was no significant difference in severity of symptoms between 6 months and 1 year (p=.53), but a 1.53 higher chance of more severe symptoms from 1 to 2 years (p<.001), and 1.33 higher chance from 2 to 3 years (p<.01).

Hospitalizations for Depression

At baseline, one in ten participants reported a history of being hospitalized for psychiatric or emotional problems; 0.9% reported hospitalization for depression in the past 12 months. Compared to baseline, hospitalizations rates for depression were similar in years 1 and 2 (0.9% and 1.1%, respectively) (p≥.05), but significantly higher (1.7%) in year 3 (p=.03).

Antidepressant Use and Counseling for Depression

At baseline, 35.3% of participants reported currently taking at least one antidepressant on a daily basis. The most frequently used types of antidepressants were selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine re-update inhibitors (SNRIs), bicyclic antidepressants (BCAs), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (in that order).

Counseling for depression was less common than antidepressant medication use, especially as a standalone treatment (table 2). Significantly more participants reported treatment for depression (counseling for depression and/or antidepressant treatment) at baseline vs. any of the follow-up visits (ps<.01). There was not a significant difference in prevalence of treatment, or its components, between any of the follow-up visits (ps>.05).

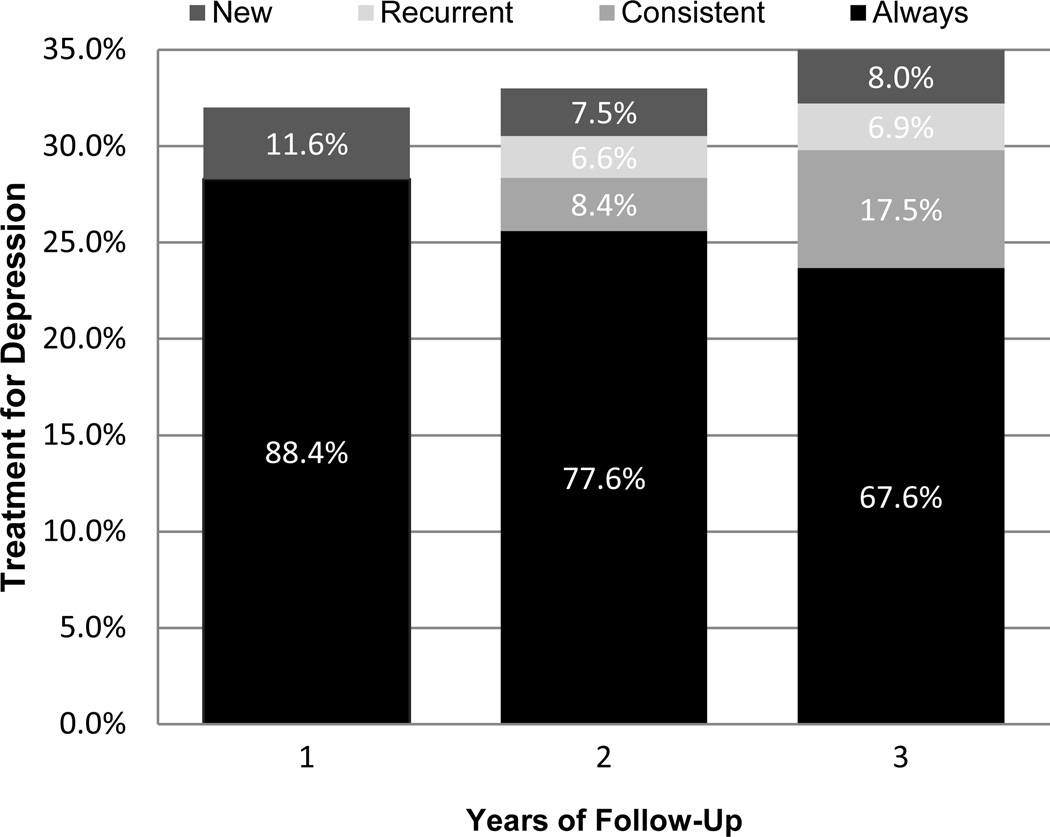

To understand patterns of treatment for depression over time, at each follow-up we categorized participants reporting either/both intervention based on prior treatment use. Among treatment users, Figure 2 shows the percentage of participants who reported treatment; 1) at each time point so far (always) 2) for the first time (new), 3) at the last time point, but not all previous time points (consistent), and 4) at any previous time point except the last time point (recurrent). In years 1–3, 8–12% of those receiving treatment for depression were new to treatment. In years 2 and 3, 7% received recurrent treatment after discontinuing treatment earlier. Over two-thirds (68%) of those receiving treatment at year 3 reported treatment at baseline and all follow-ups.

FIGURE 2. Patterns of treatment for depression over timea.

aPrevalence of treatment for depression at each time point was determined with General Linear Mixed Models using all observations. Among those reporting treatment, complete data at all previous time points was required to determine history of treatment (553 of 618 reporting treatment at 1 year, 455 of 564 reporting treatment at 2 years, and 377 of 545 reporting treatment at 3 years)

RYGB vs. LAGB

There was no significant difference in BDI score, distribution of depressive symptom severity categories, or treatment for depression between participants who underwent RYGB vs. LAGB at baseline or follow-ups (ps>.05). There also was no significant difference between procedures in change in BDI scores, depressive symptom severity categories, or treatment for depression from baseline to each follow-up or from each follow-up to the next, with two exceptions: RYGB vs. LAGB patients had a statistically significant larger decrease in BDI score from baseline to 1 year (mean change −3.7 vs. −2.9, respectively; p<.01), which was driven by the more favorable change in BDI score from 6 months to 1 year (mean change −0.4 vs. 0.4, respectively; p<.01). Due to the rarity of hospitalizations for depression, we were unable to fit a model to test whether there was a difference in hospitalization rate between RYGB vs. LAGB, taking into account a possible interaction with time. When testing the baseline data only, there was not a significant difference in hospitalizations for depression between procedures (Chi-square; p=0.97). However, when looking at the hospitalization rate for depression over 3 years, there was a significant difference in hospitalization rate for depression between RYGB and LAGB (p<.01), with a greater percentage of RYGB patients reporting hospitalizations. For example, at 1 year, 1.2% of RYGB reported a hospitalization for depression vs. 0% of LAGB; at 3 years, 2.1% vs. 0.6%, respectively.

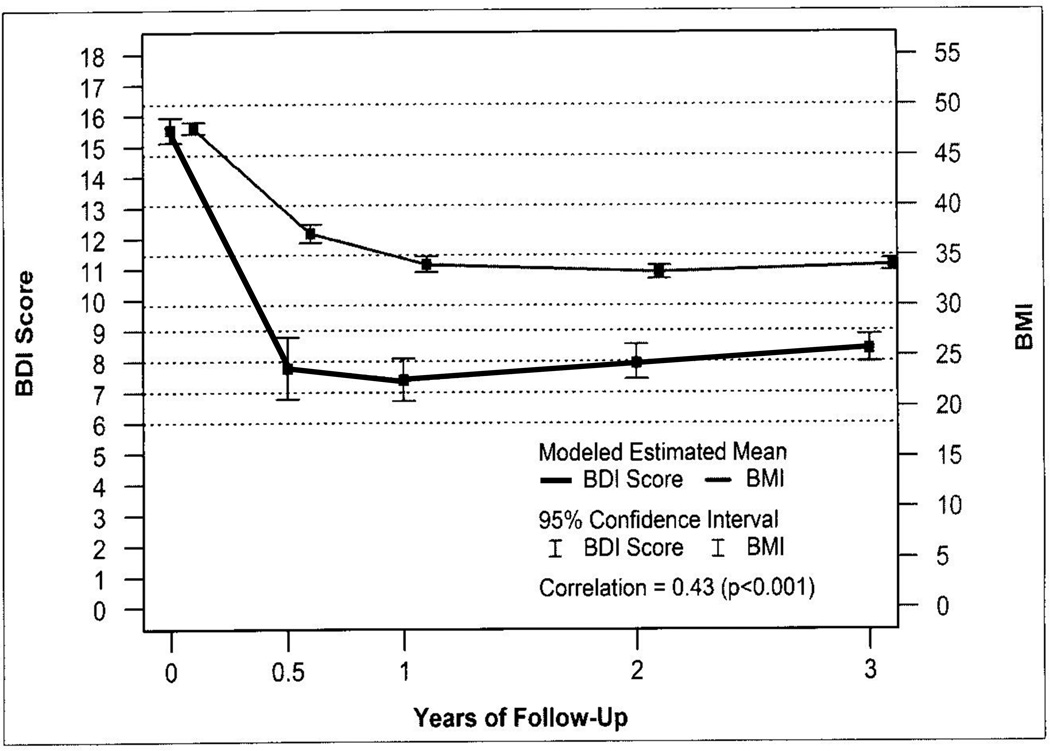

Change in Body Mass Index and Depressive Symptoms

The change in BDI was significantly associated with change in BMI, but the correlation was weak (r=.15; p<.001). However, as shown in figure 3, when analysis was limited to those with depressive symptomatology (BDI ≥ 10) at baseline, the correlation was moderate (r=.43; p<.001).

FIGURE 3.

Latent growth model testing the correspondence between changes in body mass index (BMI) with parallel change in Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score trajectory among those with baseline depressive symptoms (BDI ≥10) (n=671) a

Discussion

The current findings document that bariatric surgery is associated with significant improvements in depressive symptoms, and a modest but significant reduction in prevalence of treatment for depression in the first year after bariatric surgery. However, data suggests that there is some, albeit small, deterioration in years 1 to 3 post-surgery.

Although having significant depressive symptoms was common at baseline (28.3%), the proportion of patients with severe symptomatology was relatively low (0.5%), compared with moderate (4.2%) and mild (23.6%) symptomatology. Still, treatment for depression was quite common, with 40% of participants reporting counseling for depression and/or daily antidepressant use prior to surgery.

Exploratory analysis indicated that baseline depressive symptoms increase the odds of reoperation within 30 days of surgery. The reason for this is unclear and difficult to discern given the number of such events. Of potential relevance is a recent analysis suggesting an increased risk of short-term adverse outcomes associated with surgery in general in individuals treated in the peri-operative period with serotonin reuptake inhibitors (28). However in our current study the finding was strongest for depression severity per se rather than antidepressants broadly or this specific subgroups of antidepressants. There are a number of possible reasons for this, including the possibility that the presence of depressive symptoms is a marker or proxy for some underlying medical problem, or that depressive patients may have more physical complaints suggesting the need for re-intervention. However, this finding is based on an exploratory analysis and clearly requires replication in another cohort.

Consistent with previous work, this study found a significant decrease in depressive symptoms following surgery. After a major decline among those with baseline scores >10 in the first 6 months, the depressive symptoms score remained steady at the 1 year follow-up. Although changes in symptoms were modest from years 1 to 2 and 2 to 3, there was a significant increase in the score during this time frame, indicating some deterioration in the improvement in mood. More striking was the change in depressive symptom severity categories; compared to baseline, participants had a twofold increased likelihood of less severe depressive symptoms at 6 months vs. only a 13% odd of less severe depressive symptoms at 3 years. Our findings are in line with two small studies in adolescents which reported similar trends in change in BDI score following surgery, with increases starting at 9 months after LAGB (n=101) (29) and 18 months after RYGB (n=16) (18). Possible explanations for a deterioration in improvement in mood after the first postoperative year include: 1) disappointment from unrealistic expectations about surgery (30); 2) weight regain and/or reoccurrence of comorbidities (31,32); 3) various nutritional deficiencies, which theoretically could present with depressive features (33); 4) relative malabsorption of antidepressants (34,35). Only a few medications have been studied, and the time course and longevity of this change is not well understood. However, significant reduction in serum levels theoretically might result in increasing depression.

The moderate correlation between change in depressive symptoms and change in BMI (r=.43; p<.001) among those with baseline depressive symptoms, is consistent with previous reports (10,11). Given the greater weight loss generally experienced with RYGB, it was surprising that change in depressive symptoms was similar between procedures at the two and three year follow-ups. Expectations regarding the amount of weight loss may have varied between groups, contributing to this finding.

There are several limitations to the current study. This is an observational study, and therefore there was no randomization to procedure, and no control of depression treatment. Measurement of depressive symptoms was based on self-report only, not structured interviews. As mentioned earlier, data on treatment with medication and counseling were assessed with different time frames. Also the indication and dosage for antidepressant use were not ascertained, and what type of practitioner prescribed the medications was not recorded. Lastly, we were underpowered to test whether likelihood of a major adverse event differed by severity of symptoms or to investigate each component of the composite endpoint.

Important strengths of this study include that LABS is the largest prospective cohort study of individuals undergoing RYGB and LAGB to date. Its multi-center design, with sites across the U.S., speaks to its generalizability. Additionally, the cohort is very carefully characterized, and assessments include four time points over the first three postoperative years, when maximum weight loss and early weight regain generally occur. However, this sample is still being followed, and longer-term follow-up will be important to better understand relationships involved.

In summary, these data document that self-reported mild to severe depressive symptoms independently increases the odds of a major adverse event within 30 days of surgery, depressive symptomatology improves following bariatric surgery, but improvement deteriorates somewhat after the first post-operative year, and change in depressive symptoms is significantly related to change in BMI.

What is already known about this subject:

Depressive symptoms are common in bariatric surgery patients

Antidepressants are commonly being prescribed for bariatric surgery candidates

Bariatric surgery results in decreased depressive symptoms short-term

What this study adds:

Prospective, longitudinal assessment of self-reported depressive symptoms in large cohort, over 3 years

The finding that depressive symptoms are usually mild, do improve after surgery, then worsen somewhat

Depressive symptoms related to weight loss and antidepressant therapy

Study Acknowledgments

This clinical study was a cooperative agreement funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Grant numbers: DCC -U01 DK066557; Columbia - U01-DK66667 (in collaboration with Cornell University Medical Center CTRC, Grant UL1- RR024996); University of Washington - U01-DK66568 (in collaboration with CTRC, Grant M01RR-00037); Neuropsychiatric Research Institute - U01-DK66471; East Carolina University – U01-DK66526; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center – U01-DK66585 (in collaboration with CTRC, Grant UL1-RR024153); Oregon Health & Science University – U01-DK66555.

LABS personnel contributing to the study include:

Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY: Paul D. Berk, MD, Marc Bessler, MD, Amna Daud, Harrison Lobdell IV, Jemela Mwelu, Beth Schrope, MD, PhD, Akuezunkpa Ude, MD Cornell University Medical Center, New York, NY: Michelle Capasso, BA, Ricardo Costa, BS, Greg Dakin, MD, Faith Ebel RD, MPH, Michel Gagner, MD, Jane Hsieh BS, Alfons Pomp, MD, Gladys Strain, PhD Mt. Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY: W. Barry Inabnet, MD East Carolina Medical Center, Greenville, NC: Rita Bowden, RN, William Chapman, MD, FACS, Lynis Dohm, PhD, John Pender MD, Walter Pories, MD, FACS Neuropsychiatric Research Institute, Fargo, ND: Jennifer Barker, MBA, Michael Howell, MD, Luis Garcia, MD, FACS, MBA, Kathy Lancaster, BA, Erika Lovaas, BS, James E. Mitchell, MD, Tim Monson, MD, Oregon Health & Science University: Chelsea Cassady, BS, Clifford Deveney, MD, Katherine Elder, PhD, Andrew Fredette, BA, Stefanie Greene, Jonathan Purnell, MD, Robert O’Rourke, MD, Lynette Rogers, Chad Sorenson, Bruce M. Wolfe, MD, Legacy Good Samaritan Hospital, Portland, OR: Emma Patterson, MD, Mark Smith, MD, William Raum, MD, Lisa VanDerWerff, PAC, Jason Kwiatkowski, PAC, Jamie Laut, MEd Sacramento Bariatric Medical Associates, Sacramento, CA: Iselin Austrheim-Smith, CCRP, Laura Machado, MD University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA: Chris Costa, BA Anita P. Courcoulas, MD, MPH, FACS, Jessie Eagleton, BS, George Eid, MD, William Gourash, MSN, CRNP, Lewis H. Kuller, MD, DrPH, Carol A. McCloskey, MD, Ramesh Ramanathan, MD, Rebecca Search, MPH, Eleanor Shirley, MA University of Washington, Seattle, WA: David E. Cummings, MD, E. Patchen Dellinger, MD, Hallie Ericson, BA, David R. Flum, MD, MPH, Katrina Golub, MPH, CCRC, Brant Oelschlager, MD, Skye Steptoe, MS, CCRC, Tomio Tran, Andrew Wright, MD Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, WA: Lily Chang, MD, Stephen Geary, RN, Jeffrey Hunter, MD, Anne MacDougall, BA Ravi Moonka, MD, Olivia A. Seibenick, CCRC, Richard Thirlby, MD Data Coordinating Center, Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Abi Adenijii, PhD, Steven H. Belle, PhD, MScHyg, Lily (Jia-Yuh) Chen, MS, Nicholas Christian, PhD, Michelle Fouse, BS, Jesse Hsu, PhD, Wendy C. King, PhD, Kevin Kip, PhD, Kira Leishear, PhD, Laurie Iacono, MFA, Debbie Martin, BA, Rocco Mercurio, MBA, Faith Selzer, PhD, Abdus Wahed, PhD National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Mary Evans, Ph.D, Mary Horlick, MD, Carolyn W. Miles, PhD, Myrlene A. Staten, MD, Susan Z. Yanovski, MD National Cancer Institute: David E. Kleiner, MD, PhD

Footnotes

All of the authors were involved in data collection, data interpretation, and writing and had final approval of the submitted version. All of the authors except Chen, Garcia, Khandelwal, and Schrope were involved in study design. Mitchell, King, and Chen were involved in data analysis and generation of figures. Mitchell, King, Chen and Flum were involved in the literature review.

Possible conflicts of interest: Bruce Wolfe (EnteroMedics and Ethicon Endosurgery); David Flum (Pacira Pharmaceuticals; Nestle Healthcare).

References

- 1.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, et al. Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santry HP, Gillen DL, Lauderdale DS. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294:1909–1917. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, Berk PD, Flum DR, Garcia L, et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA. 2013;310:2416–2425. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rydén A, Torgerson JS. The Swedish Obese Subjects Study—what has been accomplished to date? Surg Obes Relat Disord. 2006;2:549–560. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karlsson J, Sjostrom L, Sullivan M. Swedish obese subjects (SOS)—an intervention study of obesity. Two-year follow-up of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and eating behavior after gastric surgery for severe obesity. Int J Obes Relat Met Disord. 1998;22:113–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O’Brien PE. Depression in association with severe obesity: Changes with weight loss. Arch Intern Med. 2009;163:2058–2065. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Moore RH, Baker AW, Gibbons LM, Raper SE, et al. Pre-operative eating behavior, post-operative dietary adherence and weight loss following gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Rerlat Dis. 2008;4:640–646. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Sarwer DB, Fabricatore AN, Crerand CE, Lipschutz PE, et al. Comparison of psychosocial status in treatment-seeking women with class III vs. class I–II obesity. Surg Obes Relat Disord. 2006;2:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham JJL, Merrell CC, Sarr M, Somers KJ, McApline D, Reese M, et al. Investigation of antidepressant medication usage after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2012;22:530–535. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0517-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Segal JB, Clark JM, Shore AD, Dominici F, Magnuson T, Richards TM, et al. Prompt reduction in use of medications for comorbid conditions after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1646–1656. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9960-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAlpine DE. How to adjust drug dosing after bariatric surgery. Current Psych. 2006;5:27–28. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powers PS, Rosemurgy AS, Coovert DL, Boyd FR. Psychosocial sequelae of bariatric surgery: A pilot study. Psychosomatics. 1988;29:283–288. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(88)72364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schowalter M, Benecke A, Lager C, Heimbucher J, Bueter M, Thalheimer A, et al. Changes in depression following gastric banding: a 5- to 7- year prospective study. Obes Surg. 2008;18:314–320. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emery CF, Fondow MDM, Schneider CM, Christofi FL, Hung C, Busy AK, et al. Gastric bypass surgery is associated with reduced inflammation and less depression: A preliminary investigation. Obes Surg. 2007;17:759–773. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thonney B, Pataky Z, Badel S, Bobbioni-Harsch E, Golay A. The relationship between weight loss and psychosocial functioning among bariatric surgery patients. Am J Surg. 2010;199:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayden MJ, Dixon JB, Dixon ME, Shea TL, O’Brien PE. Characterization of the improvement in depressive symptoms following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2011;21:328–335. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0215-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Assimakopoulos K, Karaivazoglou K, Panayiotopoulos S, Hyphantis T, Iconomou G, Kalfarentzos F. Bariatric surgery is associated with reduced depressive symptoms and better sexual function in obese female patients: A one-year follow-up study. Obes Sur. 2011;21:362–366. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0303-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Zwaan M, Enderle J, Wagner S, Mühlhans B, Ditzen B, Gefeller O, et al. Anxiety and depression in bariatric surgery patients: A prospective, follow-up study using structured clinical interviews. J Affect Disord. 2011;133:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeller MH, Reiter-Purtill J, Ratcliff MB, Inge TH, Noll JG. Two-year trends in psychosocial functioning after adolescent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:727–732. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholtz S, Bidlake L, Morgan J, Fiennes A, El-Etar A, Lacey JH, et al. Long-term outcomes following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: Post-operative psychological sequelae predict outcome at 5-year follow-up. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1220–1225. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlsson J, Taft C, Rydén A, Sjöström L, Sullivan M. Ten-year trends in health-related quality of life after surgical and conventional treatment for severe obesity: The SOS intervention study. Int J Obes (London) 2007;31:1248–1261. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flum Dr, Belle SH, King WC, Wahed AS, Berk P, Chapman W, et al. Peri-operative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:445–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belle SH, Berk PD, Courcoulas AP, Flum DR, Miles CW, Mitchell JE, et al. Safety and efficacy of bariatric surgery: Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belle SH, Berk PD, Chapman W, Christian NJ, Courcoulas AP, Dakin G, et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Longitudinal Assessments of Bariatric Surgery-2 (LABS-2) study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:926–935. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory. Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molenberghs G, Kenward MG. Missing Data in Clinical Studies. 1st ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2007. Terminology and framework; pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Auerbach AD, Vittinghoff E, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Young JQ, Lindenauer PK. Perioperative use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risks for adverse outcomes of surgery. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1075–1081. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sysko R, Devlin MJ, Hildebrant TB, Brewer SK, Zitsman JL, Walsh BT. Psychological outcomes and predictors of initial weight loss outcomes among severely obese adolescents receiving laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1351–1357. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, Womble LG, Foster GD, McGuckin BG, Schimmel A. Psychosocial aspects of obesity and obesity surgery. Surg Clin NA. 2001;81:1001–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiménez A, Casamitjana R, Flores L, Viaplana J, Corcelles R, Lacy A, et al. Long-term effects of sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on type 2 diabetes mellitus in morbidly obese subjects. Ann Surg. 2012;256:1023–1029. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318262ee6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schenthaner G, Brix JM, Kopp HP, Schernthaner GH. Cure of type 2 diabetes by metabolic surgery? A critical analysis of the evidence in 2010. Diabet Care. 2011;34:5355–5360. doi: 10.2337/dc11-s253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, Garvey WT, Hurley DL, McMahon MM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the peri-operative nutritional, metabolic, and non-surgical support of the bariatric surgery patient-2013 update. Obesity. 2013;21:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roerig JL, Steffen K, Zimmerman C, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Cao L. Preliminary comparison of sertraline levels in post-bariatric surgery patients versus matched non-surgical cohort. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roerig JL, Steffen KJ, Zimmerman C, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Cao L. A comparison of duloxetine plasma levels in post-bariatric surgery patients versus matched non-surgical control subjects. J Clin Psychopharm. 2013;33:479–484. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182905ffb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]