Abstract

As a result of their military experience, veterans with mental health problems may have unique motivations for seeking help from clergy. Patterns and correlates of seeking pastoral care were examined using a nationwide representative survey that was conducted among veterans of post-9/11 conflicts (adjusted N = 1,068; 56% response rate). Separate multivariate logistic regression models were used to examine veteran characteristics associated with seeking pastoral care and seeking mental health services. Among post-9/11 veterans with a probable mental disorder (n = 461) – defined as a positive screen for posttraumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, or alcohol misuse – 20.2% reported talking to a “pastoral counselor” in the preceding year, 44.7% reported talking to a mental health professional, and 46.6% reported talking to neither. In a multivariate analysis for veterans with a probable mental disorder, seeing a pastoral counselor was associated with an increased likelihood of seeing a mental health professional in the past year (OR: 2.16; 95% CI: [1.28, 3.65]). In a separate bivariate analysis, pastoral counselors were more likely to be seen by veterans who indicated concerns about stigma or distrust of mental health care. These results suggest that pastoral and mental health care services may complement one another and underscore the importance of enhancing understanding and collaboration between these disciplines so as to meet the needs of the veterans they serve.

Keywords: Veterans, Pastoral Care, Chaplain, Mental Health, Stigma

Veterans who have served since September 11, 2001 have faced wartime challenges that are distinct from those faced by veterans of previous conflicts. Their deployments are longer and more frequent (Pew Research Center, 2011); their likelihood of surviving combat casualties is higher (Cordesman & Sullivan, 2006; Wood, 2011); their enemy is defined less clearly (Aukerman, 2008); and they are more likely than veterans from previous eras to report that reintegrating into civilian life is difficult (Pew Research Center, 2011). These challenges place veterans at heightened risk for suffering from conditions such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder, and alcohol misuse (Hoge et al., 2004; Jacobson et al., 2008; Milliken, Auchterlonie, & Hoge, 2007; Vasterling et al., 2006). As more veterans of post-9/11 conflicts return home to civilian life, their mental health and readjustment difficulties will impose a substantial challenge on the systems and care providers to which they turn for help.

Many of these veterans are likely to turn to clergy. In the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), clergy were significantly more likely to be contacted by persons seeking treatment for a mental disorder (24% turned to clergy) than were psychiatrists (17%) or medical doctors (17%) (Wang, Berglund, & Kessler, 2003). Of those who sought help from clergy, 56% were seen exclusively by the clergyperson (i.e., did not see another care provider). Although data from the NCS and the NCS Replication suggest some decline over recent decades in reliance on clergy for provision of mental health care services (Wang et al., 2006, 2003), clergypersons remain a significant resource for individuals seeking mental health care. There are a number of reasons and hypotheses for why people with mental health problems turn to clergy: clergypersons are familiar and accessible (Weaver, Revilla, & Koenig, 2002); they tend to be less stigmatized than mental health care professionals (Milstein, Manierre, & Yali, 2010); they are frequently the first responders to crises (Oppenheimer, Flannelly, & Weaver, 2004); they often provide free or affordable care; and they are more likely than a mental health care provider to share a common worldview with the individual seeking care (Curlin et al., 2007).

For military service members and veterans who are suffering from mental health problems, there are additional potential motivations for contacting clergy. Perhaps most significant, service members and veterans are from a military culture that assigns an important and distinctive role to military chaplains. Chaplains in the military fulfill a wide array of duties, including advising commanding officers and providing confidential counsel and support to service members in distress. As a result of their commitment to confidentiality and their involvement in the daily lives of military personnel, chaplains may be identified by service members as the safest and most accessible point of contact for an emotional problem (Nieuwsma et al., 2013). In a recent study of military service personnel in the United Kingdom, it was discovered that 3 of every 4 service members with a mental health diagnosis did not access medical help for their problem but instead turned to informal sources of help like chaplains (Iversen et al., 2010). In the US, military chaplains have been recognized by the Department of Defense as playing a crucial role in the detection, treatment, and triaging of serious mental health problems, such as suicidality (Department of Defense Task Force on the Prevention of Suicide by Members of the Armed Forces, 2010). This model of military chaplains as a trusted resource may translate for many of the veterans who receive health care through the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), where chaplains provide services in a healthcare context. Slightly over half of chaplains in VA are themselves veterans, and, similar to military chaplains, VA chaplains understand that they may be perceived as a less stigmatizing point of contact than mental health professionals (Nieuwsma et al., 2013).

Clergypersons may have a particularly critical role to play for veterans who have experienced a traumatic event, given that such experiences frequently appear to have an impact on an individual’s religiosity and spirituality. Half of the 120 individuals who participated in the DSM-IV Field Trial Study on PTSD reported a change in their religiosity following a trauma, with 30% becoming less religious and 20% becoming more religious (Falsetti, Resick, & Davis, 2003). Similarly, Vietnam and post-9/11 veterans in treatment for PTSD have been found to suffer from significant religious and spiritual struggles (Drescher & Foy, 1995). Experiences at war appear to place many veterans at risk not only for PTSD but also for “moral injury” (Litz et al., 2009) – i.e., psychological and spiritual damage resulting from wartime experiences that transgress one’s moral code – with some evidence to suggest that veterans with PTSD are motivated to seek care less by their symptom severity than by a search to renew meaning in life (Fontana & Rosenheck, 2004, 2005). Such veterans are more likely to turn not only to mental health providers but also to clergy (Fontana & Rosenheck, 2005).

The present study extends previous research by examining data from the National Post-Deployment Adjustment Survey (NPDAS), a nationally representative survey of post-9/11 veterans. We examined the frequency of pastoral care utilization, the characteristics of veterans who seek pastoral care, the association between pastoral care and receipt of mental health services, and the relationship between seeking pastoral care and perceiving obstacles to obtaining mental health services among veterans with a probable mental disorder.

Methods

The National Post-Deployment Adjustment Survey methodology has been described in detail elsewhere (Elbogen et al., 2013). We provide a summary here, with a focus on methodological attributes unique to the current study. IRB approval was obtained prior to conducting the study.

Participants

A random sample of 3,000 veterans, with oversampling of women veterans, was selected from a database of over 1 million U.S. military personnel who had served since September 11, 2001. The random sample was drawn by the VA Environmental Epidemiological Service (EES) in May 2009 from a roster developed by the Defense Manpower Data Center. All participants were either separated from active duty or were in the Reserves / National Guard. A total of 63 veterans from the random sample did not have a complete address or were deceased, and an additional 438 had an incorrect address. Of the remaining 2,499 eligible study participants, 1,388 completed the survey – a 55.5% corrected response rate. Analyses of response rates based on age, gender, race / ethnicity, branch of the military, and geographic location indicated that the sample is representative of the post-9/11 veteran population.

Survey Procedures

Surveys were completed between July 2009 and April 2010. The Dillman Method (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2009) was used to contact study participants in two phases: 1) surveys were sent to 500 veterans in a pilot group to identify any technical problems, with respondents receiving $40 compensation; 2) surveys were sent to the remainder of the sample with respondents receiving $50 compensation. The estimated time needed to complete the survey was 30-35 minutes. Participants could complete a paper version of the survey or an online version; 80% chose the online option. There were no significant diagnostic or demographic differences between either online vs. paper survey completers, between those compensated $40 or $50, or between early vs. later responders to invitations to complete the survey.

Measures

The National Post-Deployment Adjustment Survey contained measures that assessed demographics, military service, combat exposure, health service utilization, perceived treatment barriers, substance misuse, and psychiatric status. Veterans were identified as having a history of arrest if they endorsed ever having been arrested for a non-violent crime, having been arrested for a violent crime, or having been in jail or prison. High combat exposure was determined as having a score below the median of 72 on the Combat Exposure Scale from the Neurocognition Deployment Health Study (King, King, & Vogt, 2003).

Use of pastoral care was assessed with the item: “How many times in the past year have you talked with a pastoral counselor (chaplain)?” For the purposes of the present study, answers to this item were dichotomized to divide participants by whether or not they saw a pastoral counselor at all during the preceding year. Use of mental health care services was assessed with two items: “How many times in the past year have you seen a psychiatrist (mental health person who can prescribe medicine)?” and “How many times in the past year have you talked with a psychologist, counselor, or any other mental health professional?” Again, responses to these questions were dichotomized, such that a non-zero answer to either question indicated receiving mental health care in the past year and answers of zero to both questions indicated receiving no mental health care.

The mental health problems of interest in the present study were PTSD, major depressive disorder (MDD), and alcohol use disorder, as these have been identified in previous research to be major mental disorders among veterans. PTSD was measured with the Davidson Trauma Scale (Davidson et al., 1997). Using a cut-off score of 48, the DTS has demonstrated 82% sensitivity, 94% specificity, and 87% diagnostic efficiency with diagnoses of PTSD in Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (McDonald, Beckham, Morey, & Calhoun, 2009). MDD was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). A cut-off score of over 10 has demonstrated sensitivity and specificity of 88% for MDD and this cutoff was used in the current study (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). Alcohol use disorder was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT), using a cut-off score of 8 to detect probable alcohol misuse (Bradley et al., 1998).

Barriers to mental health service use were assessed based on measures used in previous research in military and veteran samples (Burnam et al., 2008; Hoge et al., 2004). The scale contains a list of 17 potential barriers to treatment, which are preceded by the instruction: “Veterans may face obstacles getting or using mental health services for a number of reasons. Please rate how much you agree or disagree with each statement as it applies to you.” Participants rated their agreement with each of the 17 statements using a 4-item response choice scale of strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree. In the current study, the 17-item scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (alpha=.91).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were weighted by gender to adjust for the intentional oversampling of women. Women make up 15.6% of the military (FY2009 Annual Demographic Profile of Military Members in the Department of Defense and US Coast Guard, 2010) but constituted 33% of the National Post-Deployment Adjustment Survey. Because women were oversampled, the weight-adjusted sample of 1,102 participants, rather than the full sample of 1,388 veterans, was used. To accomplish this, female cases were assigned a weight of .38 each while male cases retained a weight of 1.00 each. Furthermore, for all analyses we excluded participants with missing information about their receipt of pastoral care (weight adjusted n = 34 [2.4%]), resulting in a final sample size of 1,068. Bivariate categorical differences were evaluated using chi-square analyses, and bivariate non-categorical differences were assessed using Student’s t-test or nonparametric Wilcoxon procedures. To estimate the association between pastoral care and the likelihood of receiving mental health services, we used multivariate logistic regression. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical software version 9 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas). All tests were conducted using a minimum significance level of 0.05.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Demographic characteristics for the overall sample and for the sub-sample of veterans with a positive mental disorder screen are presented in Table 1. In the overall sample, 17.8% (n = 190) of veterans reported seeing a pastoral counselor in the preceding year and 27.7% (n = 296) reported seeing a mental health professional (7.3% reported seeing both). Overall, 43.2% of veterans (n = 461) screened positive for at least one of the following three mental disorders: PTSD (n = 214; 20.0% of overall sample); major depressive disorder (n = 255; 23.9%); or alcohol misuse (n = 289; 27.1%). Veterans with a positive screen significantly differed from those veterans with a negative mental disorder screen on all measured demographic and military experience characteristics except race and gender. For example, veterans with a probable mental disorder were more likely to be younger, unmarried, unemployed, and homeless in the past year, and more likely to have a lower household income, a history of arrest, and a military experience that included multiple or over yearlong deployments with high combat exposure (Table 1). Veterans with a positive screen were more likely to only see a mental health professional (33.2% vs. 10.6%; p<0.001) or see both a pastoral counselor and a mental health professional (11.5% vs.4.1; p<0.001) than those veterans with a negative mental disorder screen. Seeing only a pastoral care provider did not vary significantly by whether or not the patient had a positive screen (8.7% vs. 11.9%; p=0.08). Of the 461 veterans with a probable mental disorder, 20.2% saw a pastoral counselor in the preceding year, 44.7% saw a mental health care provider, and 46.6% saw neither.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and military experience of post-9/11 veterans.

| Mental Disorder Screen Results

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Veterans (n=1,068)

|

Positive Screen (n=461) | Negative Screen (n=607) | p-value | |

| % | % | % | ||

| Received care services | 38.2 | 53.4 | 26.7 | <0.001 |

| Pastoral counselor only | 10.5 | 8.7 | 11.9 | 0.08 |

| MH care only | 20.4 | 33.2 | 10.6 | <0.001 |

| Both pastoral and MH care | 7.3 | 11.5 | 4.1 | <0.001 |

| Positive mental disorder screen | 43.2 | 100.0 | n/a | |

| PTSD | 20.0 | 46.4 | ||

| MDD | 23.9 | 55.3 | ||

| Alcohol misuse | 27.1 | 62.8 | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age < 33 years | 49.4 | 62.0 | 39.8 | <0.001 |

| Male | 84.3 | 84.6 | 84.0 | 0.7 |

| Currently married | 60.9 | 50.0 | 69.1 | <0.001 |

| White | 70.8 | 71.4 | 70.6 | 0.8 |

| Education beyond HS | 81.0 | 78.0 | 83.3 | 0.02 |

| Currently employed | 81.9 | 76.4 | 86.2 | <0.001 |

| Have children | 64.6 | 60.1 | 68.5 | 0.003 |

| Homeless in past year | 4.5 | 8.5 | 1.6 | <0.001 |

| Household income > $50K | 53.0 | 40.7 | 62.4 | <0.001 |

| History of arrest | 18.9 | 28.5 | 11.6 | <0.001 |

| Church attendance at least once a week | 21.7 | 16.5 | 25.6 | <0.001 |

| Military experience | ||||

| Multiple deployments | 27.0 | 31.4 | 23.7 | 0.004 |

| Over yearlong deployment | 26.2 | 31.6 | 22.1 | <0.001 |

| High combat exposure | 44.0 | 59.7 | 32.1 | <0.001 |

| Officer | 16.8 | 10.8 | 21.4 | <0.001 |

| Reserve or National Guard | 47.6 | 40.1 | 53.3 | <0.001 |

Note. Percentages and numbers are calculated for participants with complete data on all measures using the weighted sample, which adjusts for the oversampling of women in the original survey and reflects the actual gender balance within the military.

MH, Mental Health; PTSD, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; MDD, Major Depressive Disorder.

Pastoral Counselor Use in Veterans with a Probable Mental Disorder

Among veterans with a probable mental disorder, those who saw a pastoral counselor were less likely than those who did not to have a positive screen for alcohol misuse (53.2 % vs. 65.2%; p=0.02) and to be white (62.0% vs. 73.4%; p=0.02; see Table 2, Column 1). They were more likely to attend church once a week (40.2% vs. 10.5%; p<0.01), to have been on multiple deployments (44.0% vs. 28.2%; p<0.01), and to have seen a mental health care professional within the past year (56.8% vs. 41.6%; p<0.01).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics and military experience of post-9/11 veterans with a positive screen for a mental disorder by whether or not they received pastoral or mental health care in the past year.

| Saw a pastoral counselor (n = 93)

|

Did not see a pastoral counselor (n = 368)

|

p-value | Saw a mental health professional (n = 206)

|

Did not see a mental health professional (n =255)

|

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |||

| Received pastoral care services | n/a | 25.6 (53) | 15.7 (40) | 0.01 | ||

| Received MH care services | 56.8 (53) | 41.6 (153) | 0.01 | n/a | ||

| Positive mental disorder screen | ||||||

| PTSD | 49.8 (46) | 45.6 (168) | 0.44 | 65.8 (135) | 30.8 (78) | <0.001 |

| MDD | 62.2 (58) | 53.6 (197) | 0.12 | 74.6 (154) | 39.8 (101) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol misuse | 53.2 (49) | 65.2 (240) | 0.02 | 54.1 (111) | 69.8 (178) | <0.001 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age < 33 years | 57.9 (54) | 63.0 (232) | 0.33 | 56.8 (117) | 66.2 (169) | 0.03 |

| Male | 85.0 (79) | 84.5 (311) | 0.85 | 80.1 (165) | 88.2 (225) | <0.001 |

| Currently married | 57.3 (53) | 48.1 (177) | 0.10 | 47.7 (98) | 51.8 (132) | 0.36 |

| White | 62.0 (58) | 73.4 (270) | 0.02 | 72.4 (149) | 70.1 (179) | 0.56 |

| Education beyond HS | 80.4 (75) | 77.4 (285) | 0.52 | 81.6 (168) | 75.0 (191) | 0.08 |

| Currently employed | 69.2 (64) | 78.2 (288) | 0.06 | 72.3 (149) | 79.7 (203) | 0.05 |

| Have children | 61.1 (57) | 59.9 (220) | 0.82 | 63.5 (131) | 57.5 (146) | 0.17 |

| Homeless in past year | 9.4 (9) | 8.3 (31) | 0.72 | 11.6 (24) | 5.9 (15) | 0.03 |

| Household income > $50K | 33.2 (31) | 42.6 (157) | 0.08 | 33.0 (68) | 47.0 (120) | <0.001 |

| History of arrest | 26.9 (25) | 28.9 (106) | 0.70 | 31.3 (65) | 26.2 (67) | 0.21 |

| Church attendance at least once a week | 40.2 (37) | 10.5 (39) | < 0.01 | 17.2 (35) | 16.0 (41) | 0.71 |

| Military experience | ||||||

| Multiple deployments | 44.0 (41) | 28.2 (104) | < 0.01 | 32.5 (67) | 30.5 (78) | 0.62 |

| Over yearlong deployment | 38.1 (35) | 30.0 (110) | 0.12 | 36.3 (75) | 27.8 (71) | 0.04 |

| High combat exposure | 61.4 (57) | 59.3 (218) | 0.70 | 68.2 (141) | 52.8 (135) | <0.001 |

| Officer | 11.0 (10) | 10.8 (40) | 0.94 | 10.4 (22) | 11.1 (28) | 0.80 |

| Reserve or National Guard | 38.8 (36) | 40.5 (149) | 0.75 | 38.6 (79) | 41.4 (106) | 0.51 |

Note. Percentages and numbers are calculated using the weighted sample, which adjusts for the oversampling of women in the original survey and reflects the actual gender balance within the military. Also, please note that seeing a pastoral counselor and seeing a mental health professional was not mutually exclusive, in fact 11.5% of veterans with a positive mental health screen saw both.

MH, Mental Health; PTSD, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; MDD, Major Depressive Disorder; HS, High School.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3, Column 1) indicated that veterans who saw a mental health professional within the past year (Odds Ratio [OR]: 2.16; 95% Confidence Interval [CI] [1.27, 3.67]) or attended church once a week (OR: 5.69; 95% CI [3.25, 9.97]) had greater odds of seeing a pastoral counselor.

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression modeling the likelihood of receiving pastoral care or mental health care in the past year among veterans with a positive mental disorder screen (n=461).

| Likelihood of receiving pastoral care in the past year | Likelihood of receiving mental health care in the past year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Saw a pastoral counselor within the past year | n/a | 2.16** | [1.28, 3.65] | |

| Saw a MH professional within the past year | 2.16** | [1.27, 3.67] | n/a | |

| Positive mental disorder screen | ||||

| PTSD | 0.74 | [0.42, 1.32] | 2.67*** | [1.69, 4.22] |

| MDD | 1.05 | [0.60, 1.83] | 3.06*** | [1.92, 4.88] |

| Alcohol misuse | 0.77 | [0.44, 1.37] | 1.21 | [0.74, 1.98] |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age < 33 years | 0.98 | [0.57, 1.70] | 0.52** | [0.32, 0.85] |

| Male | 1.68 | [0.93, 3.06] | 0.44** | [0.27, 0.72] |

| Currently married | 1.60 | [0.92, 2.79] | 0.85 | [0.53, 1.36] |

| White | 0.63 | [0.37, 1.05] | 1.70* | [1.06, 2.74] |

| Education beyond HS | 1.07 | [0.60, 1.91] | 1.72 | [0.99, 2.98] |

| Currently employed | 0.70 | [0.40, 1.22] | 1.15 | [0.71, 1.87] |

| Have children | 0.67 | [0.39, 1.15] | 1.23 | [0.77, 1.96] |

| Homeless in past year | 1.28 | [0.58, 2.82] | 1.52 | [0.73, 3.19] |

| Household income > $50K | 0.67 | [0.36, 1.24] | 0.55* | [0.33, 0.90] |

| History of arrest | 0.96 | [0.56, 1.63] | 1.37 | [0.85, 2.23] |

| Church attendance at least once a week | 5.69*** | [3.25, 9.97] | 0.68 | [0.38, 1.23] |

| Military experience | ||||

| Multiple deployments | 1.86 | [0.99, 3.49] | 0.74 | [0.42, 1.31] |

| Over yearlong deployment | 0.91 | [0.47, 1.78] | 1.47 | [0.83, 2.62] |

| High combat exposure | 0.81 | [0.46, 1.40] | 1.53 | [0.94, 2.49] |

| Officer | 1.05 | [0.43, 2.53] | 1.36 | [0.68, 2.75] |

| Reserve or National Guard | 1.16 | [0.69, 1.97] | 0.87 | [0.56, 1.34] |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Note: Multivariate logistic regression using the weighted sample

MH, Mental Health; PTSD, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; MDD, Major Depressive Disorder; HS, High School.

Likelihood of Receiving Mental Health Care Services among Veterans with a Probable Mental Disorder

In veterans with a probable mental disorder, those who saw a mental health professional were more likely than those who did not to have seen a pastoral counselor in the past year (25.6% vs. 15.7%; p=0.01) and to have a positive screen for PTSD (65.8% vs. 30.8%; p<0.001) or MDD (74.6% vs. 39.8%; p<0.001; see Table 2, Column 2). They were less likely to have a positive screen for alcohol misuse (54.1% vs. 69.8%; p<0.001). Compared to veterans who did not see a mental health professional, those who did were also more likely to be older than 33 years old (p=0.03), female (p<0.001), currently unemployed (p=0.05), homeless in the past year (p=0.03), with a household income of less than $50,000 (p<0.001), or military experience that included high combat experience (p<0.001).

In a multivariate analysis examining the odds of receiving mental health services in the preceding year (Table 3, Column 2), veterans with a probable mental disorder were significantly more likely to receive mental health services if they saw a pastoral counselor within the past year (OR: 2.16; 95% CI [1.28, 3.65]). Other significant predictors of mental health care services receipt included having a positive screen for PTSD or MDD, being female, white, or having an annual household income of less than $50,000.

Perceived Obstacles to Mental Health Care

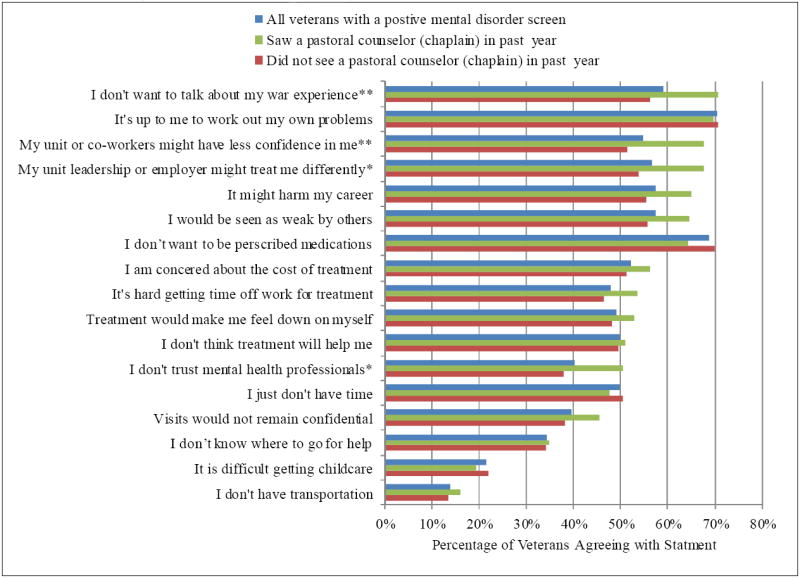

Among veterans with a probable mental disorder, those who had seen a pastoral counselor were more likely than those who had not to endorse the following as obstacles to receiving mental health care (Figure 1): not wanting to talk about their war experience (p=0.008); believing that they would be treated differently by their co-workers (p=0.004) or employers (p=0.013); and not trusting mental health professionals (p=0.02). These obstacles reflect concern about stigma and distrust of mental health care.

Figure 1. Obstacles to receiving mental health services among post-9/11 veterans with a positive mental disorder screen by whether received pastoral care.

Obstacles are presented in order of most commonly to least commonly agreed with statements among post-9/11 veterans who saw pastoral counselors.

* p<0.05 ** p<0.01

Discussion

Over 2 million veterans who have served since 9/11 are now either separated from the military or in the National Guard / Reserve (Kapp & Torreon, 2013; Office of Public Health: Veterans Health Administration, 2011). Extrapolating from findings in the present study, we estimate that 300,000 to 400,000 of these veterans – a slight majority of whom are likely to suffer from PTSD, MDD, or alcohol misuse – will see a pastoral counselor at least once during the course of a year. If anything, this is likely an underestimate, as participants in the current study may not have considered meaningful encounters with their pastor, rabbi, imam, or other clergyperson as constituting seeing a “pastoral counselor (chaplain),” per the wording of the item in the present survey.

Despite this and other methodological differences between the Post Deployment Adjustment Survey and the National Comorbidity Survey, the 20% of veterans with probable mental disorders who reported seeing a pastoral counselor in the present study compares closely with the 24% of persons seeking treatment for a mental health problem who reported turning to clergy in the National Comobidity Survey (Wang et al., 2003). Veterans in the National Post Deployment Adjustment Survey who had probable mental disorders and saw pastoral counselors were less likely to be seen solely by a clergyperson (43%) than their general population counterparts in the National Comorbidity Survey (56%). In fact, the multivariate regression analysis from the present study found that veterans with a probable mental disorder were significantly more likely to receive mental health services if they had seen a pastoral counselor within the past year.

It is possible to interpret this positive correlation between seeing a pastoral counselor and seeing a mental health provider as refuting the common perception of a divide between mental health and religious establishments, suggesting instead that representatives of these two establishments often work together collaboratively. Alternatively, this finding may imply little about cross-disciplinary collaboration between clergypersons and mental health professionals and indicate instead that veterans who seek help often do so via multiple avenues. This second interpretation seems more likely when considering evidence that mental health care providers who work with veterans tend to pay little attention to issues of religion and spirituality (Baroody, Everson, & Figley, 2011; Rosmarin, Pirutinsky, Green, & McKay, 2013). Additionally, a recent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD) study of chaplains and mental health professionals found that integration between these disciplines is often limited due to cross-disciplinary difficulties establishing familiarity and trust (Nieuwsma et al., 2013). Such limited integration is concerning given that chaplains in both VA and DoD report seeing veterans and service members with psychosocial problems more frequently than they see overtly spiritual problems (Nieuwsma et al., 2013). In DoD, chaplains serve primarily in operational contexts (rather than healthcare settings) and therefore often serve as frontline mental health providers for service members (Department of the Army, 2012). In VA, chaplains all serve in healthcare settings, mostly inpatient, yet are still major providers of psychosocial services (Nieuwsma et al., 2013; Zullig et al., 2012). One study of 1,199 male colorectal cancer patients seen across VA over a two-year period found that chaplaincy was the most frequently utilized form of psychosocial support – more than social work, psychology, psychiatry, or mental health nursing (Hamilton, Jackson, Abbott, Zullig, & Provenzale, 2011). Another study of 761 veterans in the Well-being Among Veterans Enhancement Study (WAVES) found current PTSD severity was positively correlated with recently seeking help from a spiritual counselor (Bonner et al., 2013).

Furthermore, the current study found that veterans with probable mental disorders who had concerns about stigma, did not want to talk about their war experiences, or did not trust mental health care providers were more likely to see a pastoral counselor than to not see a pastoral counselor. This is consistent with the finding that VA and DoD chaplains perceive veterans and service members as commonly seeking help from chaplains instead of mental health professionals (Nieuwsma et al., 2013). Importantly, this same study of VA and DoD chaplains found that over 95% of chaplains value the role of mental health professionals and believe that the two disciplines can closely collaborate. Given these findings, we offer the following recommendations for public sector mental health care providers wanting to improve their collaboration with clergy: 1) become familiar with the roles and responsibilities of local public sector chaplains (e.g., VA/DoD), including their linkages to community clergy; 2) help destigmatize mental health care and improve access to care by reaching out to public sector chaplains, community clergy, and other faith group leaders to equip them via psychoeducation with capacities to identify mental health problems, make appropriate referrals, provide education about mental health services, and address misconceptions or fears about mental health treatment; 3) develop a shared understanding between public sector chaplains and mental health providers around how to coordinate care – including how to screen and refer patients bidirectionally (i.e., from mental health to chaplains and chaplains to mental health), document care, respect confidentiality, and communicate about patients’ needs; and 4) when possible and appropriate, consider opportunities for synergizing care practices (e.g., developing a care plan wherein individual psychotherapy and chaplain-led spirituality groups complement and build on each other, or offering a group co-led by a mental health professional and chaplain).

One noteworthy finding from this study was that while positive screens for PTSD and MDD were found in the bivariate analysis to increase the likelihood of receiving mental health care (Table 2), a positive screen for alcohol misuse actually made it less likely that veterans received either mental health care or pastoral care. In further exploring this finding in the overall sample (not just the subsample of those with a probable mental disorder), we found that veterans with probable alcohol misuse were not more or less likely to receive pastoral care but were significantly less likely to receive mental health care. However, multivariate regressions run in both the overall sample and in the subsample of those with probable mental disorders (Table 3) indicate that the relationship between alcohol misuse and receipt of care services (either mental health or pastoral) becomes non-significant once controlling for covariates – including gender, age, PTSD and MDD screens, and church attendance. This suggests that alcohol misuse is not an important predictor of receiving mental health or pastoral care services once confounding variables are considered.

Of further note were the findings that certain demographic characteristics predicted receipt of mental health care. In both the bivariate analyses and multivariate logistic regression, making below $50,000 per year, being female, or being older than 33 years old increased the likelihood that a veteran with a positive mental health screen received mental health care, but none of these characteristics was a statistically significant predictor for receiving pastoral care. Also, race influenced receipt of mental health and pastoral care services, with the multivariate regression finding that non-whites were less likely to talk with a mental health professional and perhaps more likely to talk with a pastoral counselor (this later correlation was significant in the bivariate analysis and marginally significant in the multivariate regression). These findings suggest that contrary to being a barrier to receipt of mental health care, lower income among post-9/11 veterans actually increases likelihood of receiving such care. Additionally, these findings indicate that it may be especially important to coordinate with pastoral counselors around meeting the mental health needs of younger veterans, male veterans, and non-white veterans, as these veterans are less likely to connect with mental health providers but no less likely to talk with pastoral care providers (in the multivariate regression, there were non-significant trends towards males as well as non-whites being more likely to talk with pastoral counselors).

This study has limitations. First, veterans suffering from mental health problems other than probable PTSD, depression, or alcohol misuse were not included in the present sample of those likely to have a mental disorder. Second, likelihood of a mental disorder was determined via self-report, though it should be noted that rates of PTSD, depression, and alcohol misuse were not low and generally comported with other national estimates (Hoge et al., 2004; Iversen et al, 2010). Third, some respondents may have interpreted “pastoral counselor (chaplain)” to reference only a subset of clergypersons, thus potentially providing an underestimate of the number of veterans who see clergy (e.g., veterans who saw imams, rabbis, preachers, or pastors may not have considered these clergypersons to necessarily be a “counselor” or “chaplain”). Fourth, it is unknown whether the pastoral counselors and mental health professionals in the current study operated inside or outside of VA. Fifth, analyses could not account for course or effectiveness of services provided by clergy or mental health care providers. Finally, in part because it is unknown whether participants saw mental health professionals before or after seeing pastoral counselors, referral patterns and other forms of collaboration between clergy and mental health care providers cannot be discerned from the current study.

Nonetheless, taken together with data from other studies, the current study underscores the importance of enhancing understanding and collaboration between mental health professionals and clergy. These two professional groups are caring for the mental and spiritual needs of many post-9/11 veterans and have the opportunity to coordinate care services so as to capitalize on each discipline’s strengths in service to veterans.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH080988), the Office of Research and Development Clinical Science and Health Services, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the VA’s Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC). The authors extend sincere thanks to the participants who volunteered for this study. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- Aukerman MJ. War, crime, or war crime?Interrogating the analogy between war and terror. In: Linnan DK, editor. Enemy combatants, terrorism, and armed conflict law: A guide to the issues. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Baroody AN, Everson RB, Figley CR. Spirituality and trauma during a time of war: A systemic approach to pastoral care and counseling. In: Everson RB, Figley CR, editors. Families under fire: Systemic therapy with military families. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2011. pp. 165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner LM, Lanto AB, Bolkan C, Watson GS, Campbell DG, Chaney EF, Rubenstein LV, et al. Help-seeking from clergy and spiritual counselors among veterans with depression and PTSD in primary care. Journal of Religion and Health. 2013;52:707–718. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9671-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, Bush KR, McDonell MB, Malone T, Fihn SD Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project. Screening for problem drinking: Comparison of CAGE and AUDIT. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13:379–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnam MA, Meredith LS, Helmus TC, Burns R, Cox RA, D’Amico E, Yochelson MR, et al. Systems of care: Challenges and opportunities to improve access to high-quality care. In: Tanielian T, Jaycaox L, editors. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Washington, DC: RAND Corporation; 2008. pp. 245–428. [Google Scholar]

- Cordesman AH, Sullivan WD. The challenge of meeting the needs of our active and reserve military. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Curlin FA, Odell SV, Lawrence RE, Chin MH, Lantos JD, Meador KG, Koenig HG. The relationship between psychiatry and religion among U.S. physicians. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1193–1198. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.9.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, Feldman ME, et al. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:153–160. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense Task Force on the Prevention of Suicide by Members of the Armed Forces. The challenge and the promise: Strengthening the force, preventing suicide and saving lives: Final report of the Department of Defense task force on the prevention of suicide by members of the armed forces. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Department of the Army. Army 2020: Generating health and discipline in the Force. Washington, DC: Department of the Army; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman D, Smyth J, Christian L. Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. 3. New York, NY: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher KD, Foy DW. Spirituality and trauma treatment: Suggestions for including spirituality as a coping resource. National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Clinical Quarterly. 1995;5:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Johnson SC, Kinneer PM, Kang H, Vasterling JJ, Beckham JC, et al. Are Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using mental health services? New data from a national random-sample survey. Psychiatric Services. 2013;64:134–141. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.004792011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falsetti SA, Resick PA, Davis JL. Changes in religious beliefs following trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:391–398. doi: 10.1023/A:1024422220163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, Rosenheck R. Trauma, change in strength of religious faith, and mental health service use among veterans treated for PTSD. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192:579–584. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000138224.17375.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, Rosenheck R. The role of loss of meaning in the pursuit of treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:133–136. doi: 10.1002/jts.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistical series pamphlet 08-10. Satellite Beach, FL: Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute; 2010. FY2009 Annual Demographic Profile of Military Members in the Department of Defense and US Coast Guard. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton NS, Jackson GL, Abbott DH, Zullig LL, Provenzale D. Use of psychosocial support services among male Veterans Affairs colorectal cancer patients. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2011;29:242–253. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2011.563346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen AC, van Staden L, Hughes JH, Browne T, Greenberg N, Hotopf M, Fear NT, et al. Help-seeking and receipt of treatment among UK service personnel. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;197:149–155. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson IG, Ryan MAK, Hooper TJ, Smith TC, Amoroso PJ, Boyko EJ, Bell NS, et al. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300:663–675. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp L, Torreon B. Reserve component personnel issues: Questions and answers (No CRS Report No RL30802) Congressional Reporting Service; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- King DW, King LA, Vogt DS. Manual for the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI): A collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences in military veterans. Boston, MA: National Center for PTSD; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, Lebowitz L, Nash WP, Silva C, Maguen S. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SD, Beckham JC, Morey RA, Calhoun PS. The validity and diagnostic efficiency of the Davidson Trauma Scale in military veterans who have served since September 11th, 2001. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW. Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:2141–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milstein G, Manierre A, Yali AM. Psychological care for persons of diverse religions: A collaborative continuum. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2010;41:371–381. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwsma JA, Rhodes JE, Jackson GL, Cantrell WC, Lane ME, Bates MJ, Meador KG, et al. Chaplaincy and mental health in the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy. 2013;19:3–21. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2013.775820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Public Health: Veterans Health Administration. Analysis of VA health care utilization among Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation New Dawn (OND) veterans. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer JE, Flannelly KJ, Weaver AJ. A Comparative analysis of the psychological literature on collaboration between clergy and mental-health professionals – Perspectives from secular and religious journals: 1970-1999. Pastoral Psychology. 2004;53:153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. The military-civilian gap: War and sacrifice in the post-9/11 era. Washington, DC: Pew Social and Demographic Trends; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rosmarin DH, Pirutinsky S, Green D, McKay D. Attitudes toward spirituality/religion among members of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2013;44:424–433. [Google Scholar]

- Vasterling JJ, Proctor SP, Amoroso P, Kane R, Heeren T, White RF. Neuropsychological outcomes of army personnel following deployment to the Iraq War. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296:519–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund PA, Kessler RC. Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Services Research. 2003;38:647–673. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Demler O, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Changing profiles of service sectors used for mental health care in the United States. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1187–1198. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver AJ, Revilla LA, Koenig HG. Counseling families across the stages of life: A handbook for pastors and other helping professionals. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wood D. Beyond the battlefield: From a decade of war, an endless struggle for the severely wounded. The Huffington Post 2011 Oct 11; [Google Scholar]

- Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Provenzale D, Griffin JM, Phelan S, Nieuwsma JA, Ryn M. Utilization of hospital-based chaplain services among newly diagnosed male Veterans Affairs colorectal cancer patients. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014;53:498–510. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]