Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of our study was to evaluate and quantify the bacterial adherence to the different components of total hip prosthesis.

Methods

The bacterial load of 80 retrieved hip components from 24 patients was evaluated by counting of colony-forming units (CFU) dislodged from component surfaces using the sonication culture method.

Results

Micro-organisms were detected in 68 of 80 explanted components. The highest bacterial load was detected on the polyethylene liners, showing a significant difference in distribution of CFU between the liner and metal components (stem and cup). Staphylococcus epidermidis was identified as the pathogen causing the highest CFU count, especially from the polyethylene liner.

Conclusions

Results of our study confirm that sonicate culture of the retrieved liners and heads, which revealed the highest bacterial loads, are reliable and sufficient for pathogen detection in the clinical diagnostic routine.

Keywords: Total hip prosthesis, Periprosthetic joint infection, Sonication culture, Microbial biofilm, Bacterial adherence, Biomaterial

Introduction

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a severe complication following arthroplasty. Associated with extended hospitalisations and patient immobilisation, it often leads to functional and emotional morbidity, as well as a substantial cost burden for the health-care system [1]. Although much effort has already been expended on reducing the incidence of PJI [2–4], the incidence after primary hip-joint arthroplasty is about 1 % [5] and after revision arthroplasty even five times higher [6, 7]. Tunney et al. concluded in their study that unrecognised infection is a potential major cause of prosthetic hip failure [8]. Bacterial adherence and subsequent biofilm formation on implant surfaces are involved in the origin and maintenance of implant-related infections [9], because the presence of biofilm hinders the microbiological diagnosis and eradication of the detached micro-organism. This is considered the key phenomenon in the pathogenesis of these infections [10]. Efforts to diagnose the causative agent on colonised implants were recently renewed with the introduction of retrieved implant sonification protocols [11–13]. With this technique, the presence of micro-organisms has been diagnosed with higher sensitivity and specificity [12–14], and a quantitative approach has been suggested as a new diagnostic criterion [11].

Experimental studies revealed that different biomaterials suffer differently from micro-organism adherence and biofilm formation, justifying component exchange in some cases of acute prosthetic joint infection. Petty et al. [15] reported a preferred adherence of micro-organisms to polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) compared with polyethylene (PE), stainless steel and cobalt–chromium (CoCr) alloys. CoCr alloys also showed experimentally a significantly higher infection susceptibility than titanium (Ti) alloys [16], and rough-surfaced Ti alloys were more prone to infection than polished Ti alloys [17].

Holinka et al. [18] evaluated the differential bacterial load on components of total knee prosthesis in patients with prosthetic joint infection with the sonication culture method. The most important finding of that study was that PE-inlay components and tibial components were most often affected by micro-organisms, but the ultra-high-molecular-weight PE (UHMWPE) components—PE inlay and patella—showed a much higher load of colony-forming units (CFU) per component than CoCr components. These clinical results, although not significant, confirm the experimental knowledge of higher bacterial adherence to UHMWPE components compared with other implant materials, but bacterial adherence was not restricted to only one of the prosthesis components. Accordingly, septic revision surgery and changing the UHMWPE components in case of early infection might reduce the load of micro-organisms in the knee joint but does not erase the infection.

Yet clinical studies confirming a preferred bacterial adherence to a certain prosthetic component of hip prosthesis are lacking. Therefore, we performed a descriptive data analysis from all culture-positive total hip prosthesis explanted between 2007 and 2011 and compared the CFU load on the different components: femoral stem, modular head, PE liner and acetabulum-cup shell. We aimed to isolate and quantify the adherent micro-organisms to the individual components to analyse the different bacterial adherence to each retrieved part and consequently, the different bacterial adherence to each biomaterial. Our hypothesis was that a separate processing of prosthetic components using the sonification method may yield additional information regarding bacterial adherence with biofilm formation on the different components in hip arthroplasty. This knowledge could support direct efforts for improving PJI detection.

Materials and methods

Between September 2007 and February 2011, we assessed 80 components of retrieved total hip prostheses from 24 consecutive patients (seventeen women and seven men). Criteria for inclusion were positive sonication cultures of explanted components. At the time of explantation, average patient age was 65.2 years, mean C-reactive protein (CRP) was 6.1 mg/dl and the operation was a second revision in the majority of cases (n = 13) (Table 1). Standard total hip prosthesis consists of four main components: femoral stem, femoral modular head, acetabular liner and acetabular-cup shell. We sonicated 16 titanium-aluminium-niobium (Ti6Al7Nb) alloy stems (Alloclassic®, Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland; SL-Plus®, Plus Orthopedics AG, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), 24 ceramic heads (Biolox®, Ceramtec GmbH, Plochingen, Germany), 24 highly cross-linked UHMWPE liners (Durasul®, Zimmer) and 16 pure titanium cups (Alloclassic® Zweymüller® CSF® Cup, Zimmer; Bicon Plus® Plus Orthopedics AG, Rotkreuz, Switzerland; Original M.E.Müller® Ring; Burch-Schneider® Reinforcement Cage, Zimmer). Patient characteristics and implant-related data are also shown in Table 1. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Medical University of Vienna.

Table 1.

Demographic and implant-related data at the time of operation (24 patients)

| Demographic and implant-related data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Characteristics | Number (%) |

| Age (years) | Mean 65.2 (range 39.3 to 90.4) | |

| CRP (mg/dl) | Mean 6.14 (range 0.3 to 23.82) | |

| Sex | M | 7 (29.2) |

| F | 17 (70.8) | |

| Type of operation | Revision | 11 (45.8) |

| Second revision | 13 (54,2) | |

| Femoral stem, Ti6Al7Nb (n = 16) | Alloclassic® | 14 (87.5) |

| SL-plus® | 2 (12.5) | |

| Femoral head, ceramic (n = 24) | Biolox® | 24 (100) |

| Liner, highly X-linked PE (n = 24) | Durasul® | 24 (100) |

| Metal-shell cup, pure titanium (n = 16) | CSF® | 9 (56.3) |

| Bicon plus® | 2 (12.5) | |

| M.E.Müller® ring | 2 (12.5) | |

| Burch-Schneider® reinforcement cage | 3 (18.7) | |

| Total number of components (n = 80) | No micro-organisms | 12 (15.0) |

| CFU ≤5 per explanted hip prosthesis or ≤3 per single component | 10 (12.5) | |

CRP C-reactive protein, Ti6Al7Nb titanium-aluminium-niobium alloy, PE polyethylene , CFU colony-forming units

The diagnosis of prosthetic infection was evaluated in accordance with the standard criteria of infection [19] on the presence of two or more cultures of joint aspirates or cultures of multiple (three to five) periprosthetic tissue samples yielding the same micro-organism, purulence surrounding the prosthesis at the time of explantation, acute inflammation consistent with infection during histopathological examination or a sinus tract that communicated with the prosthesis. Aseptic failure was defined as failure in the absence of any of these criteria.

For sonication, explanted hip components were separately packed into sterile, wide-mouth Nalgene® containers and covered with Ringer’s solution. The containers were then closed tight. Intact containers were sterilised by pressure-heat at 2 bar, 121 °C for 15 minutes. All specimens were to be transported to the laboratory and processed within six hours. Containers were vortexed for 30 s using a Labinco Vortex Mixer L-46 (Breda, The Netherlands) then subjected to sonication for five minutes in a Bandelin Sonorex Super RK 100 (frequency 35 kHz, RF-power p 80/320 W, Berlin, Germany), followed by additional vortexing for 30 seconds. The resulting sonicate fluid was plated in 500-μl aliquots onto aerobic Columbia-sheep-blood agar plates for five days and on anaerobic Schaedler-sheep-blood agar for seven days. Micro-organisms were enumerated and classified by routine microbiological techniques. A total of 50 ml of sonication fluid was centrifuged at 2,600 rpm for 15 minutes, and the sediment was Gram stained. All bacteria were counted and identified by standard methods (API or VITEK, bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Susceptibility testing was performed using the disc diffusion test according to the guidelines of the CLSI. All isolated organisms were collected and frozen at −72 °C. Cultures were quantified by counting the number of colonies that grew in the plate, adjusted to the number of CFU, and then adjusted to CFU/sample. A total number of CFU of ≤5 per explanted hip prosthesis or ≤3 per single component was defined as contamination.

Statistical methods

To investigate the distribution of CFU on the different hip components, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed, as the variables did not follow a normal distribution in the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and the Friedman test was highly significant. Pearson correlation was performed to evaluate the correlation between total bacterial load (CFU) and patient age, gender and preoperative CRP. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 22 (SPSS Inc./IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

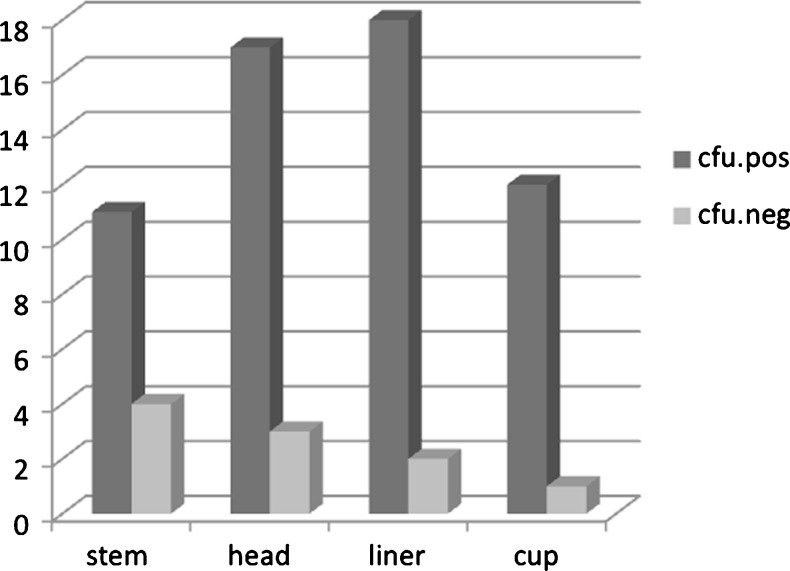

All 24 prostheses (24 patients) showed positive sonication culture. Micro-organisms were detected in 68 of 80 explanted components. Ten components were defined as contaminated (CFU ≤5 per explanted prosthesis or ≤3 per single component), leaving 58 components (11 stems, 17 heads, 18 acetabulum liners, 12 shell cups) from 20 patients (20 prostheses) for analysis (Fig. 1, Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of total hip prostheses components with positive and negative pathogen detection

Table 2.

Micro-organisms detected in sonication cultures

| Number of micro-organism-positive components | Number of detected colony-forming units | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hips | Components | Stem | Head | Liner | Cup | Micro-organism | Stem | Head | Liner | Cup | Total CFU |

| 5 | 16 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 332 | 2,560 | 5000 | 3,000 | 10,892 |

| 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Staphylococcus capitis | 3 | 1,016 | 1,000 | 1,128 | 3,147 |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Staphylococcus aureus | 1000 | 480 | 480 | 112 | 2,072 |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Corynebacterium | 300 | 300 | 1,000 | 300 | 1,900 |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Staphylococcus lugdonensis | 20 | 1,000 | 34 | 2 | 1,056 |

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Enterococcus faecalis | 17 | 17 | 1,000 | 0 | 1,034 |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Streptococcus anginosus | 100 | 100 | 300 | 300 | 800 |

| 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Sphingomonas paucimobilis | 0 | 160 | 35 | 16 | 211 |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Streptococcus constellatus | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 200 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Propionebacterium acnes | 0 | 0 | 128 | 0 | 128 |

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Enterococcus durans | 23 | 23 | 23 | 0 | 69 |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Klebsiella oxytoca | 0 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 102 |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Pseudomonas stutzeri | 0 | 13 | 13 | 0 | 26 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Aerobe Sporenbildner | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Enterobacter cloacae | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| 0 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | Enterococcus faecalis | 10 | 30 | 30 | 15 | 85 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Sphingomonas paucimobilis | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 0 | 0 | 1,000 | 0 | 1,000 |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Staphylococcus lugdonensis | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Candida tropicalis | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Fusobacterium nucleatum | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| 20 | 58 | 11 | 17 | 18 | 12 | 1,805 | 5,746 | 10,180 | 5,007 | 21,651 | |

Secondary positive micro-organism contamination not included in total results

Micro-organisms detected in sonication cultures are described in Table 2. Staphylococcus epidermidis (including one case of methicillin-resistant micro-organism) was identified as the pathogen causing the highest CFU count (10,92), especially from the PE liner (5,000 CFU) and was isolated from the majority of components (n = 16), particularly from head (n = 5) and liner (n = 5). The highest bacterial load was dislodged from PE liners [10,180 CFU; mean 566, range 0–5,000, standard deviation (SD) 1,178], followed by ceramic heads (5,746 CFU; mean 319, range 0–2560, SD 647), metal-shell cups (5,007 CFU; mean 278, range 0–3000, SD 731) and stem (1,805 CFU; mean 82, range 0–1000, SD 246). The highest CFU load per component was detected from PE liners (566), followed by the cup (417) and head (338). CFU load for the Ti6Al7Nb-alloy stem was much lower (164). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test revealed a highly significant difference between CFU distribution in stem and liner (P = 0.005) and a significant difference between cup and liner (P = 0.028). There were no significant differences between the other components.

In four patients, polymicrobial infection was detected on eight components (four liners, two heads, one stem, one cup) (Enterococcus faecalis, Sphingomonas paucimobilis, Staphylococcus epidermidis). In another four patients, micro-organisms were detected on ten components, with a maximum of two CFU per component and four per prosthesis classified as being contaminated. In these patients clinical signs and symptoms as well as histological and microbiological criteria for infection were absent. Additionally, we found only very weak correlations between total CFU on removed components and patient age (r = 0.07), gender (r = 0.2) and pre-operative CRP (r = 0.19).

Discussion

The development of implant sonication as a diagnostic tool for prosthetic joint infection is an important advancement for improving the sensitivity of conventional techniques. Several studies verified the importance of sonicated fluid cultures for improving microbiological diagnostics [11, 14, 20]. Understanding the aetiology of infection is of great importance, as it allows selection of the best antimicrobial therapy [10, 12]. Holinka et al. tested the sonication method for all explants in their clinical routine and found a significant benefit for detecting micro-organisms from component surfaces compared with tissue culture [13]. In their study, sonicated fluid cultures were defined as positive if >5 CFU of the same organism grew on aerobic or anaerobic plates, according to recommendations by Trampuz et al. [11]. Controversially, analysing the number of CFU in their study, Esteban et al. could establish no breakpoint between significant and nonsignificant isolates [12].

The most important finding of our study is the significantly higher bacterial adherence to highly cross-linked UHMWPE liners compared with metal implant materials of the stem and cup. In fact, we found a significant difference in bacterial load between PE liner and Ti6Al7Nb femoral stem and the pure titanium cup. CFU distribution between the ceramic components, such as liners and heads were not significant. These results confirm the lower bacterial adherence to metal, especially to titanium. This is confirmed by basic experimental knowledge that micro-organisms are more adherent to polymers, which supposedly could present a higher risk of infection than metals, especially titanium [15, 16]. In contrast, a clinical study by Gomez-Barrena et al. showed no significant preference of bacteria to infected components of 12 knee and 20 hip prostheses [21]. They explained this finding as due to variability in micro-organism adherence, even from the same species, and by the influence of host susceptibility, immune reaction, perfusion status and underlying local conditions. Bacterial adherence on each type of biomaterial even displayed a trend towards less adherence to UHMWPE in knee and to hydroxyapatite in hip implants in their study. Despite their conclusions about the prevailing effect of individual patient characteristics and micro-organisms, hip infections were apparently more severe cases with more isolated micro-organisms per surface unit when compared with the knee. We found similar results when comparing results of isolated knee components as those published by Holinka et al. [18], with no significant difference between components, in contrast to the results of our study. In contrast to total knee implants, components of total hip prostheses, especially the femoral stem, is osseointegrated in femoral bone, offering a smaller area for micro-organism detection compared with the liner and head. The unequal distribution of CFU between PE liners and ceramic heads in our study shows that not only component location and integration but also different biomaterials have an influence on differing bacterial loads detected on individual components.

Additionally there is evidence in the literature [22] that the incidence of infection is lower with the use of tantalum compared with titanium prostheses. This is particularly true when components were used in revisions performed to treat infection. This may be related to the three-dimensional structure and pore size of tantalum prosthesis, which prohibits bacterial growth and the formation of biofilm.

Similar to results reported by Gomez-Barrena et al. [21], the majority of components (n = 16) in our study yielded growth of Staphylococcus epidermidis, which caused the highest CFU count (10,892) on sonication. Although we found unequal micro-organism distribution between components, CFU in the individual stem or cup were as high as 1,000 in some cases (Table 2). Thus, in revision surgery due to sepsis, partial component exchange of head and liner to cure PJI may not be sufficient.

A limitation of this study was that we observed a high variability of micro-organism species, resulting in a relatively low number of components and joints per each micro-organism detected by sonication culture. Furthermore, it was not possible to differentiate the influence of individual patient susceptibility and the initial origin of infection, especially in cases of prior revisions.

In conclusion, we confirmed that sonication is a reliable method of detecting bacteria from component surfaces of retrieved total hip prostheses. Evaluating separate components improved the detection of different micro-organisms on the biofilm of different prosthetic materials, especially on PE components, thus improving micro-organism detection rate in PJI. Janz et al. [23] confirmed these results, also reporting an improved detection rate by using multiple sonicated fluid cultures. We also found it was possible to identify all detected micro-organisms simply by evaluating the liner and head. The remaining components did not reveal additional micro-organisms. Therefore, our study confirm that sonicated culture of retrieved liners and heads are reliable and sufficient for pathogen detection in the clinical diagnostic routine.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sonja Reichmann for the excellent technical work in sonication of explanted components and culture testing.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Klouche S, Sariali E, Mamoudy P. Total hip arthroplasty revision due to infection: a cost analysis approach. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charnley J, Eftekhar N. Postoperative infection in total prosthetic replacement arthroplasty of the hip-joint. With special reference to the bacterial content of the air of the operating room. Br J Surg. 1969;56:641–649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800560902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lidwell OM, Elson RA, Lowbury EJ, Whyte W, Blowers R, Stanley SJ, Lowe D. Ultraclean air and antibiotics for prevention of postoperative infection. A multicenter study of 8,052 joint replacement operations. Acta Orthop Scand. 1987;58:4–13. doi: 10.3109/17453678709146334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lidwell OM, Lowbury EJ, Whyte W, Blowers R, Stanley SJ, Lowe D. Effect of ultraclean air in operating rooms on deep sepsis in the joint after total hip or knee replacement: a randomised study. Br Med J. 1982;285:10–14. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6334.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1645–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips JE, Crane TP, Noy M, Elliott TS, Grimer RJ. The incidence of deep prosthetic infections in a specialist orthopaedic hospital: a 15-year prospective survey. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006;88:943–948. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B7.17150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi HR, von Knoch F, Kandil AO, Zurakowski D, Moore S, Malchau H. Retention treatment after periprosthetic total hip arthroplasty infection. Int Orthop. 2012;36:723–729. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1324-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tunney MM, Patrick S, Curran MD, Ramage G, Hanna D, Nixon JR, Gorman SP, Davis RI, Anderson N. Detection of prosthetic hip infection at revision arthroplasty by immunofluorescence microscopy and PCR amplification of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3281–3290. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3281-3290.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costerton JW (2005) Biofilm theory can guide the treatment of device-related orthopaedic infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res 7–11 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Del Pozo JL, Patel R. Clinical practice. Infection associated with prosthetic joints. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:787–794. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0905029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trampuz A, Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, Hanssen AD, Unni KK, Osmon DR, Mandrekar JN, Cockerill FR, Steckelberg JM, Greenleaf JF, Patel R. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:654–663. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esteban J, Gomez-Barrena E, Cordero J, Martin-de-Hijas NZ, Kinnari TJ, Fernandez-Roblas R. Evaluation of quantitative analysis of cultures from sonicated retrieved orthopedic implants in diagnosis of orthopedic infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:488–492. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01762-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holinka J, Bauer L, Hirschl AM, Graninger W, Windhager R, Presterl E. Sonication cultures of explanted components as an add-on test to routinely conducted microbiological diagnostics improve pathogen detection. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:617–622. doi: 10.1002/jor.21286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janz V, Wassilew GI, Hasart O, Matziolis G, Tohtz S, Perka C. Evaluation of sonicate fluid cultures in comparison to histological analysis of the periprosthetic membrane for the detection of periprosthetic joint infection. Int Orthop. 2013;37:931–936. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-1853-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petty W, Spanier S, Shuster JJ, Silverthorne C. The influence of skeletal implants on incidence of infection. Experiments in a canine model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1236–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cordero J, Munuera L, Folgueira MD. The influence of the chemical composition and surface of the implant on infection. Injury. 1996;27(Suppl 3):SC34–SC37. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(96)89030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cordero J, Munuera L, Folgueira MD. Influence of metal implants on infection. An experimental study in rabbits. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1994;76:717–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holinka J, Pilz M, Hirschl AM, Graninger W, Windhager R, Presterl E. Differential bacterial load on components of total knee prosthesis in patients with prosthetic joint infection. Int J Artif Organs. 2012;35:735–741. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berbari EF, Hanssen AD, Duffy MC, Steckelberg JM, Ilstrup DM, Harmsen WS, Osmon DR. Risk factors for prosthetic joint infection: case–control study. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1247–1254. doi: 10.1086/514991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trampuz A, Piper KE, Hanssen AD, Osmon DR, Cockerill FR, Steckelberg JM, Patel R. Sonication of explanted prosthetic components in bags for diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection is associated with risk of contamination. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:628–631. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.628-631.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomez-Barrena E, Esteban J, Medel F, Molina-Manso D, Ortiz-Perez A, Cordero-Ampuero J, Puertolas JA. Bacterial adherence to separated modular components in joint prosthesis: a clinical study. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:1634–1639. doi: 10.1002/jor.22114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Del Gaizo DJ, Kancherla V, Sporer SM, Paprosky WG. Tantalum augments for Paprosky IIIA defects remain stable at midterm followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:395–401. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2170-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janz V, Wassilew GI, Hasart O, Tohtz S, Perka C. Improvement in the detection rate of PJI in total hip arthroplasty through multiple sonicate fluid cultures. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:2021–2024. doi: 10.1002/jor.22451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]