Introduction

Understanding the pathophysiology of hypertension requires a solid foundation in hemodynamic principles, an understanding of cardiovascular, renal, and endocrine physiology, and knowledge regarding the neural pathways involved in blood pressure control. The length constraints for this manual do not allow detailed coverage of basic physiological principles, so it may be helpful for the reader to review the physical principles of hemodynamics and the basic physiological processes responsible for the regulation of cardiac output, total peripheral resistance, and blood pressure.

Basic Hemodynamics

Static hydrodynamic considerations establish that, at steady state, mean arterial pressure is a function of cardiac output and peripheral vascular resistance, such that,

Thus, it follows that increased arterial pressure (hyper-tension) occurs when cardiac output or peripheral vascular resistance or both are inappropriately elevated. Nevertheless, it is also well recognized that these parameters are dynamically regulated by a plethora of systems and factors which impinge on one or more determinants of either cardiac output or peripheral vascular resistance. In certain conditions, an increased cardiac output, driven by increased cardiac contractility and heart rate reflecting increased sympathetic tone, contributes to a sustained hypertension or prehypertension. Importantly, the cyclical pumping nature of the heart imposes a heavy burden on the distensible characteristics of the aortic tree which is continuously subjected to a changing volume as the hydraulic pressure increases during systole and falls in diastole. A healthy distensible aortic tree can accommodate the influx from the left ventricle with a lesser increase in pressure than occurs in various disease states or in older subjects having reduced aortic distensibility. Indeed, decreased distensibility is primarily responsible for aortic stiffness leading to isolated systolic hypertension often found in elderly patients. In response to the same stroke volume from the left ventricle, the aortic pressure increases more and the fall off during diastole is faster and greater, thus accounting for the increased pulse pressure which provides an estimate of aortic distensibility. Nevertheless, the cardiovascular system is a closed hydrodynamic compartment, and there are both rapidly adjusting systems and long-term mechanisms providing regulatory inputs.

A cardinal factor responsible for long-term regulation of cardiac output and blood pressure is blood volume. Homeostatic regulation of blood volume is essential for the long-term control of blood pressure. Importantly, this long-term control of blood volume is closely associated with the long-term regulation of extracellular fluid volume (ECFV). In turn, the long-term regulation of ECFV is dependent on the ability of the kidneys to excrete sufficient salt to maintain normal sodium balance, ECFV, and blood volume. Decreases in sodium excretory capability under conditions of normal or increased intake lead to chronic increases in ECFV and blood volume. There is a direct relationship between salt intake and plasma volume, even in normal individuals. Thus, the long-term maintenance of blood pressure depends, in large part, on our ability to excrete extra salt which is regulated by many neurohumoral mechanisms. If there is chronic blood volume expansion or decreases in vascular capacitance, these conditions predis-pose to hypertension. A principal role of the kidneys is salt and water homeostasis which links the long-term control of blood volume, cardiac output, and arterial pressure with sodium balance and the control of ECFV. Nevertheless, this fundamental mechanism which maintains the volume within the cardiovascular system is subject to a large array of regulatory inputs which reflect the incredible complexity of the cardiovascular system.

As shown in Figure 1, homeostatic regulation of blood pressure involves many interacting systems that sense and respond to various environmental changes by continuously adjusting hemodynamic, endocrine, neural, and kidney mechanisms as needed to maintain the blood pressure. In essence, the two major determinants of arterial pressure, cardiac output, and peripheral resistance are continuously regulated by a combination of short-term and long-term mechanisms. On a long-term basis, mean circulatory pressure which determines venous return depends on blood volume. Superimposed hemodynamic, neural, and endocrine mechanisms interact to provide rapid adjustments and maintain blood pressure within the normal range. Derangements in any of these systems can lead to alterations in arterial pressure. The neurohumoral systems listed represent only a partial list of the many possible factors that can contribute to regulation of hemodynamics and arterial pressure. In addition, only a few of the most critical systems can be covered in this brief presentation.

Figure 1.

Homeostatic mechanisms regulating sodium balance and arterial pressure. ECFV, extracellular fluid volume.

Renal Function

The intrarenal hemodynamic environment determines the formation of the glomerular filtrate, the reabsorption of fluid by the peritubular capillaries, and the maintenance of a hyperosmotic medullary environment. These forces are controlled by the vascular smooth muscle cells of the renal vasculature which respond to neural, hormonal, and paracrine stimuli. Derangements in renal hemodynamics may give rise to hypertension and chronic kidney disease. About 20% of the cardiac output (renal fraction) goes to the kidneys which means that expressed per unit weight, renal blood flow (RBF) is 10–50 times greater than for most other organs and in excess of what is needed to provide the oxygen and metabolic needs of the kidneys.

The unique nature of the dual microvascular beds in the kidney, namely the glomerular and postglomerular vascular beds provide separation of the filtering process from the re-absorptive process. The preglomerular resistance, localized primarily in the afferent arterioles, and the postglomerular resistance, imposed primarily by the efferent arterioles, result in the “nesting” of the glomerular capillaries between the afferent and the efferent arterioles and allow the maintenance of a high glomerular pressure that is responsible for the formation of the glomerular filtrate. The low hydrostatic pressure within the peritubular capillaries allows the elevated plasma colloid osmotic pressure to predominate and thus be responsible for the return of the tubular reabsorbate to the circulation.

Renal regulatory systems are divided into those originating outside the kidney (such as circulating vasoactive agents or renal sympathetic nerve activity) and those intrinsic to the kidney. The autoregulatory intrinsic mechanisms are responsible for maintaining RBF and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) within narrow limits in the face of a variety of external perturbations including alterations in arterial pressure. This autoregulatory mechanism is important in stabilization of the glomerular pressure and filtered volume to the tubules under conditions of moderate variations in cardiovascular function. Even small increases in arterial pressure can cause marked increases in filtered load and sodium excretion in the absence of normal autoregulatory capability. Thus, autoregulation is a continuously operating negative feedback control system that maintains an optimum filtered load in the face of varying external influences, particularly changes in blood pressure. Autoregulation also contributes to the kidney's reserve capability that can be used in response to a variety of injurious process that could otherwise lead to diminished renal function. The autoregulatory responses are mediated by active adjustments of smooth muscle tone primarily in the afferent arterioles leading to highly efficient autoregulation of both RBF and GFR and regulation of the intrarenal pressures in the glomerular and peritubular capillaries. Hypertensive conditions are often associated with impairment of autoregulatory capability.

The highly efficient regulation of the filtered load to the tubules allows the sophisticated tubular transport mechanisms in the various nephron segments to determine the reabsorption of salt and other substances in accord with the needs of our body. With regard to tubular transport of sodium, about 60%–70% of the filtered sodium is reabsorbed by the proximal tubule, and another 15%–20% is reabsorbed by the loop of Henle with the reabsorption of the remaining fraction regulated by distal nephron segments. Fine regulation of sodium excretion is handled by distal transport mechanisms, and mutations in the activity of distal sodium transport mechanisms have been associated with hypertension and hypotension. Length constraints do not allow detailed consideration of the many tubular transport mechanisms regulating sodium reabsorption; however, some of these are often upregulated in hypertensive conditions.

Endothelial Function

There are many paracrine agents that influence the vascular smooth muscle cells of the microvasculature. One particularly intriguing area of interest is related to the formation and release of paracrine agents by adjoining endothelial cells. Endothelial cells respond to various physical stimuli (eg, shear stress) and hormonal agents (eg, thrombin and bradykinin) to release vasoactive factors. The substance that has received the most intense investigation recently is nitric oxide (NO) which was originally called endothelium-derived relaxing factor. NO is formed intracellularly by NO synthases which form NO from l-arginine. In endothelial cells, NO is formed constitutively and diffuses out of the cell into adjoining cells. Through stimulation of soluble guanylate cyclase and increased cGMP levels in smooth muscle cells, NO exerts powerful vasodilator actions. Because NO is derived from arginine, several nonmetabolizable analogs of arginine have been used to block the formation of NO. Blocking NO formation causes a 25%–40% increase in vascular resistance with increases in blood pressure and decreases in tissue blood flow. Some of this increase in vascular resistance is thought to be mediated by increased levels of reactive oxygen species and an enhanced activity of the renin–angiotensin system during NO blockade. Endothelial dysfunction that occurs in hypertension impairs the ability of endothelial cells to make sufficient amounts of NO and thus contributes further to the increased vascular resistance and hypertension.

As depicted in Figure 2, it is important to understand that there are many additional paracrine factors formed and released by the endothelial cells. Endothelial cells produce both vasoconstrictor and vasodilatory prostanoid products of arachidonic acid. In addition, metabolites of the cyto-chrome p450 enzymatic system also mediate dilator and constrictor signals to the vascular smooth muscle cells. Endothelin is another powerful vascular vasoconstrictor that is released by endothelial cells.

Figure 2.

Multiplicity of endothelium-vascular smooth muscle interactions with release of vasoactive agents. Examples of constricting and relaxing factors are indicated. ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; Ang, angiotensin; EDCF, endothelium-derived constricting factor; EDHF, endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor; NO, nitric oxide; TXA2, thromboxane A2.

Endothelial cells also contain abundant amounts of angiotensin-converting enzymes (ACE) which are responsible for forming angiotensin II (Ang II) from angiotensin I (Ang I), serving as one way of regulating the local concentration of Ang II. In summary, endothelial cells lining the blood vessels throughout the body contribute in a crucial manner to the overall integrity of the vasculature and produce many vasoactive paracrine factors thus playing a major role in regulating peripheral vascular resistance.

Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System

Ang II exerts many pleotropic actions on vascular, neural, and epithelial tissues throughout the body. Because of the widespread clinical use of drugs that antagonize or block the renin–angiotensin system, this topic has a very high degree of clinical relevance. The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system is one of the most important regulators of blood pressure, sodium excretion, and the slope of the pressure natriuresis relationship. Renin is an aspartyl proteinase that cleaves the decapeptide Ang I, from angiotensinogen, an α2-globulin formed primarily by the liver but also in the kidneys and other tissues. The major site of renin formation in the kidneys is the juxtaglomerular epithelioid cells of afferent arterioles. Renin release is stimulated by decreased sodium intake, reduced extracellular fluid and blood volume, decreased arterial pressure, and increased sympathetic activity. Ang I generation is determined by renin activity because substrate availability is usually ample. The decapeptide is subsequently cleaved to the octapeptide, Ang II, by ACE. ACE is abundant in the lungs, bound to endothelial cells, and is also found in many other organs including the kidney. The luminal surfaces of renal tubules have abundant ACE and form angiotensin peptides within proximal and distal nephron segments.

Although several peptides are formed by RAS, Ang II is the major active metabolite and exerts pleotropic effects on many different organs and tissues. The actions of Ang II help conserve sodium and maintain arterial pressure. These include stimulation of aldosterone by the adrenal gland, vascular constriction, increased sympathetic tone, and increased tubular sodium reabsorption. When inappropriately elevated, Ang II causes hypertension. The major effects of Ang II are mediated by AT1 receptors that are dominant in adults. AT1 receptors are extensively distributed throughout the vasculature. AT2 receptors are thought to counteract AT1 actions but have low expression in adults and are more prominent in fetal and newborn kidneys. AT2 receptors may also be increased in certain cardiovascular diseases.

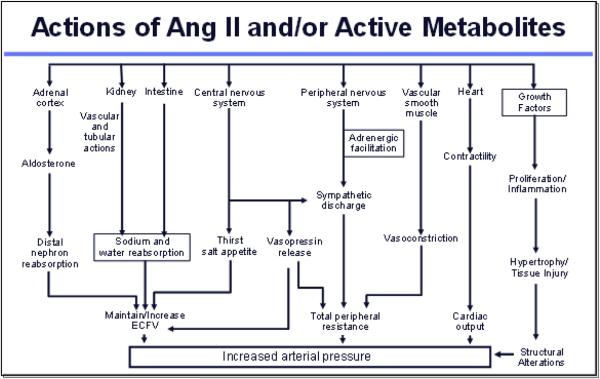

Ang II has an overall effect to minimize renal fluid and sodium losses and to maintain ECFV and arterial blood pressure. In addition to its vascular effects, Ang II stimulates aldosterone release, enhances tubular sodium reabsorption rate, stimulates thirst, and enhances sympathetic nerve activity. As shown in Figure 3, Ang II exerts powerful effects on many tissues which elicit decreases in blood flow and increases in vascular resistance. Essentially, every organ system in the body responds to Ang II, and Ang II is produced locally in many tissues.

Figure 3.

Ang II, angiotensin II; ECFV, extracellular fluid volume.

AT1 receptor antagonists, ACE inhibitors, and the recently available renin inhibitors are frequently used clinically to block the effects of endogenous Ang II in various conditions such as hypertension, congestive heart failure, and diabetes. During conditions associated with enhanced Ang II activity, inhibition of the renin–angiotensin system increases blood flow and reduces peripheral vascular resistance which leads to reductions in arterial pressure.

At the cellular level, Ang II increases cytosolic [Ca2+] by enhancing Ca2+ entry through voltage dependent Ca2+ channels and by mobilization of the Ca2+ from intracellular storage sites. Ang II-induced depolarization of vascular smooth muscle cells elicits opening of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and subsequent vasoconstriction. Accordingly, some of the vasoconstrictor responses to Ang II are blocked by calcium channel blockers.

Sympathetic Nervous System

Blood flow and vascular resistance are markedly influenced by extrinsic stimuli including stress, trauma, hemorrhage, pain, and exercise. These conditions elicit increases in sympathetic nervous activity which directly increases vascular resistance. Strong activation of the sympathetic nerves results in marked vasoconstriction mediated by α-adrenoreceptors, leading to decreases in blood flow. The kidneys are important targets of increased sympathetic tone which decreases RBF and GFR, increases renin release, and stimulates tubular sodium and water reabsorption. Increases in renal sympathetic nerve activity can be a part of an overall sympathetic response or may be more selective. Decreases in renal nerve activity can be elicited reflexively through cardiopulmonary receptors and renorenal reflexes.

Heightened sympathetic outflow also causes many systemic vascular effects by stimulating hypertrophy and proliferation, medial thickening, endothelial dysfunction, and increased arterial stiffness. The actions on the heart also include left ventricle hypertrophy, tachycardia, and increased incidence of arrhythmias. Renal effects also include decreased blood flow and GFR, increased sodium reabsorption, RAS activation, glomerulosclerosis, and proteinuria. Metabolic actions include insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis. The sympathetic nervous system also interacts with the immune system by contributing to inflammation, leukocyte activation, extravasation, increased oxidative stress, and production of chemokines and cytokines. Through the myriad of actions, the neural pathways can exert formidable alterations contributing to the development and progression of hypertension.

Low-level renal nerve stimulation elicits increases in renin release mediated by a direct action on JGA cells via β-adrenergic receptor activation, along with increases in tubular sodium reabsorption even in the absence of perceptible renal vasoconstriction. Moderate levels of renal nerve stimulation elicit parallel increases in afferent and efferent arteriolar resistance leading to greater decreases in RBF than in GFR. With higher stimulation frequency, a powerful preglomerular vasoconstrictor response predominates and the filtration coefficient is decreased, causing decreases in GFR. The increase in renal vascular resistance induced by α-adrenoceptors represents a pathway for α-adrenoceptor influence over renin secretion. The influence of neural activity on the medullary circulation may also be of importance, because outer medullary descending vasa recta receive sympathetic innervation. The tonic influence of the sympathetic nervous system on renal hemodynamics under unstressed conditions is relatively low.

The renal circulation is also subject to influences by the adrenal medulla which releases epinephrine systemically in response to many stress conditions. Smooth muscle-containing vessels of all sizes, from the main renal arteries to afferent and efferent arterioles, respond to exogenous norepinephrine and epinephrine. Afferent arterioles are more sensitive than efferent arterioles to the vasoconstrictive effect of norepinephrine.

The kidneys also have sensory receptors that are activated by various stimuli and send signals back to the central nervous system via afferent nerves. These afferent signals from the kidney and other hormones can activate multiple signals throughout the body and contribute to the augmentation of cytokines throughout the body.

Because of the important role that renal nerves have in regulating renal function, the renal ablation approach has been recently developed to control blood pressure in patients who are refractory to pharmacologic treatment. The available clinical trials have shown favorable long-term effects by reducing blood pressure in individuals with resistant hypertension. The consequences of renal ablation are due to blockade of both afferent and efferent neural pathways. Some studies suggest that ablation of afferent renal nerve activity leads to a suppression of overall sympathetic vasoconstrictor drive which contributes to the antihypertensive actions.

Footnotes

This article is part of the American Society of Hypertension Self-Assessment Guide series. For other articles in this series, visit the JASH home page at www.ashjournal.com.

Suggested References

- 1.Abboud FM, Harwani SC, Chapleau MW. Autonomic neural regulation of the immune system: implications for hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2012;59:755–62. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.186833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appel LJ, Frohlich ED, Hall JE, Pearson TA, Sacco RL, Seals DR, et al. The importance of population-wide sodium reduction as a means to prevent cardiovascular disease and stroke: a call to action from the American Heart Association. Circ. 2011;123:1138–43. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820d0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arendshorst WJ, Navar LG. Renal circulation and glomerular hemodynamics. In: Schrier RW, editor. Diseases of the Kidney and Urinary Tract. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 54–95. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briet M, Boutouyrie P, Laurent S, London GM. Arterial stiffness and pulse pressure in CKD and ESRD. Kidney Int. 2012;82:388–400. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis JT, Rao F, Naqshbandi D, Fung MM, Zhang K, Schork AJ, et al. Autonomic and hemodynamic origins of pre-hypertension: central role of heredity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:2206–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esler MD, Lambert EA, Schlaich M, Navar LG. Point: Counterpoint: the dominant contributor to systemic hypertension: chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system vs. activation of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:1996–2002. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00182.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher JP, Paton JF. The sympathetic nervous system and blood pressure in humans: implications for hyper-tension. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26:463–75. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grassi G, Bertoli S, Seravalle G. Sympathetic nervous system: role in hypertension and in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21:46–51. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32834db45d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaess BM, Rong J, Larson MG, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Levy D, et al. Aortic stiffness, blood pressure progression, and incident hypertension. JAMA. 2012;308:875–81. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobori H, Nangaku M, Navar LG, Nishiyama A. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: from physiology to the pathobiology of hypertension and kidney disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:251–87. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krum H, Schlaich M, Whitbourn R, Sobotka PA, Sadowski J, Bartus K, et al. Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension: a multi-centre safety and proof-of-principle cohort study. Lancet. 2009;373:1275–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60566-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navar LG, Arendshorst WJ, Pallone TL, Inscho EW, Imig JD, Bell PD. The renal microcirculation. In: Tuma RF, Duran WN, Ley K, editors. Handbook of Physiology: Microcirculation. Academic Press; 2008. pp. 550–683. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navar LG, Hamm LL. Hypertension and the Kidney. Current Medicine, Inc.; Philadelphia: 1999. The kidney in blood pressure regulation. In: Wilcox CS, editor. Atlas of Diseases of the Kidney. pp. 1.1–1.22. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Kobori H, Navar LG. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system. In: Carey RM, editor. Hypertension and Hormone Mechanisms. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey USA: 2007. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]