Abstract

Mutations in Parkin are the second most common known cause of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Parkin is an ubiquitin E3 ligase that monoubiquitinates and polyubiquitinates proteins to regulate a variety of cellular processes. Loss of parkin’s E3 ligase activity is thought to play a pathogenic role in both inherited and sporadic PD. Here we review parkin biology and pathobiology and its role in the pathogenesis of PD.

Introduction

Familial Parkinson’s disease (PD) with specific genetic defects may account for fewer then 10 percent of all cases of PD1, however, the identification of these rare genes and their functions has provided tremendous insight into the pathogenesis of PD and opened up new areas of investigation2–7 (Table 1). Five genes have been clearly linked to PD, and a number of other genes or genetic linkages have been identified that may cause PD. The first “PD-gene” (PARK1) was the gene encoding the presynaptic protein, alpha-synuclein8, 9. The second “PD-gene” (PARK2) is caused by mutations in the gene for parkin10, and it leads to autosomal recessive PD (AR-PD) and is the subject of this review. The third “PD-Gene” (PARK7) results from mutations in DJ-111. The fourth “PD-Gene” (PARK6) results from mutations in PTEN Kinase 1 (PINK1)12. The fifth “PD-Gene” (PARK8) is due to mutations in LRRK213, 14. Mutations in alpha-synuclein, parkin, DJ-1, PINK1, LRRK2 definitely cause PD. The identification of the genes for PARK1 (α-synuclein), PARK2 (parkin), PARK7 (DJ-1), PARK6 (PINK1) and PARK8 (LRRK2) has led to new insights and direction in PD research and pathogenesis.

Table 1.

Loci and genes linked to familial PD

| Locus | Chromosomal Location |

Gene | Mode of Inheritance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PARK1 / PARK4 | 4q21.3 | α-synuclein | Autosomal Dominant |

| PARK2 | 6q25.2-27 | Parkin | Autosomal Recessive |

| PARK3 | 2p13 | Unknown | Autosomal Dominant |

| PARK5 | 4p14 | UchL1 | Autosomal Dominant |

| PARK 6 | 1p35-p36 | PINK1 | Autosomal Recessive |

| PARK7 | 1p36 | DJ-1 | Autosomal Recessive |

| PARK8 | 12p11q13.1 | LRRK2/Dardarin | Autosomal Dominant |

| PARK9 | 1p36 | ATP13A2 | Autosomal Recessive (Kufer-Rakeb Syndrome) |

| PARK10 | 1p32 | Unknown | Late-Onset Susceptibility Gene |

| PARK11 | 2q36-37 | Unknown | Late-Onset Susceptibility Gene |

| PARK12 | Xq21-q25 | Unknown | X-Linked |

| PARK13 | 2p13.1 | Omi/HtrA2 | Autosomal Dominant |

Parkin

Parkin belongs to a family of proteins with conserved ubiquitin-like domain (UBL) and really interesting new gene (RING) finger motifs15. Mutations in parkin cause autosomal recessive Parkinson’s disease (AR-PD)10. Mutations in parkin are the most common cause of AR-PD16, 17. In addition, mutations in parkin may play a role in sporadic PD16–18. In the limited neuropathologic studies of patients with parkin mutations, there is a selective loss of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra and loss of noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus with accompanying gliosis19. There a few cases with α-synuclein positive inclusions or Lewy pathology, the hallmark feature of PD20–22, and others that lack of α-synuclein positive inclusions19. A few cases also show Tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles23, 24. The relationship of parkin to α-synuclein pathology requires additional study as it is not clear from the human post-mortem studies published to date whether parkin and α-synuclein participate in the same pathogenic pathway. However, clinical studies would suggest that PD due to parkin and α-synuclein mutations are distinct clinical diseases, albeit with PD symptomatology17.

Parkin and Ubiquitination

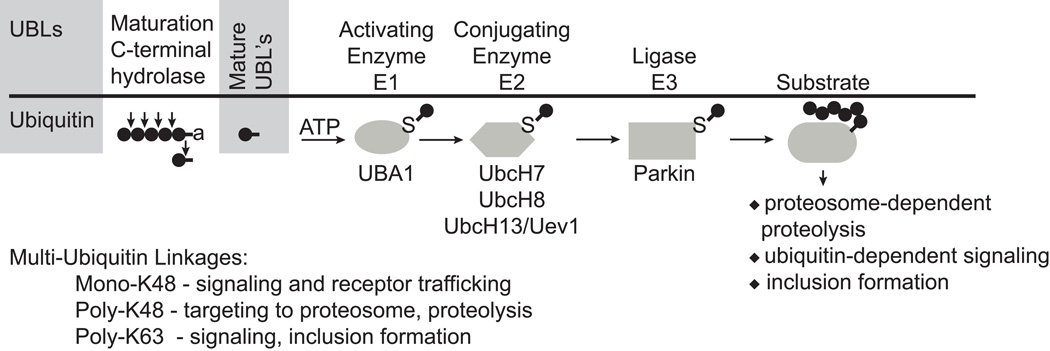

Parkin functions as an ubiquitin E3 protein-ligase (Figure 1)25–27. Parkin contains two RING finger domains separated by an in-between RING domain IBR. Ubiquitin is a 76-amino-acid protein produced from a number of ubiquitin precursor proteins encoded in the human genome. It is covalently attached to the lysine residue of substrate proteins in a process called ubiquitination. The process of ubiquitination occurs through the transfer of an ubiquitin molecule from an activated E1-enzyme to the conjugating E2 enzyme, where an E3-ligase catalyzes the transfer of the ubiquitin molecule from the E2 enzyme to a target substrate28. The E3-enzyme usually confers substrate specificity and acts as a scaffold to facilitate the stoichiometric requirements of the covalent attachment of ubiquitin. The ubiquitin chain elongation factors, otherwise known as E4s, can catalyze the multi-ubiquitination of proteins bound to the E2–E3 complexes. The ubquitination reaction may end with the attachment of a single ubiquitin molecule, a process called mono-ubiquitination, or the attachment of an ubiquitin molecule to several lysine residues in the target protein (multiple mono-ubiquitination). E3-ligase proteins can also promote the attachment of ubiquitin molecules to lysine residues in the ubiquitin molecule already attached to a target substrate including on lysine residues 48 or 63 in the ubiquitin molecule to form a chain of ubiquitin molecules. A chain of at least four lysine-48 linkages act as a signal for proteasomal degradation. Monoubiquitination and lysine-63 chains tend to function in non-degradative signaling roles. Parkin appears to perform monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination with either lysine-48 or lysine-63 linkages.

Figure 1.

Parkin is multifunctional ubiquitin E3 ligase. Parkin functions in the ubiquitin proteasome system as an E3 ligase. Ubiquitination requires the E1 activating enzyme and the E2 conjugating enzyme. Parkin utilizes a variety of E2s including UBCH7, UBCH8 and UbcH13/Uev1. Parkin utilizes a variety of linkages including monoubiquitination and polyubiquitanation via lysine-48 and lysine-63 chains.

Monoubiquitination by parkin may under certain circumstances be involved with receptor turnover29. Parkin mediated lysine-48 linkages are involved with protein degradation and parkin mediated lysine-63 linkages with protein inclusions30, 31. Parkin appears to use both UbcH7 and UbcH8 as its E225, 26. Parkin also utilizes the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated E2’s Ubc6 and Ubc732. Additionally, parkin interacts with the E2 complex UbcH13/Uev1 in mediating lysine-63-linked polymerization of ubiquitin33. The function and type of ubiquitin modification that parkin mediates is probably largely defined on the cellular context and the ubiquitin machinery that parkin utilizes. Purified, in vitro parkin ubiquitination reactions suggest that parkin mediates primarily mono-ubiquitination reactions34, 35. However, addition of the chaperone-dependent ubiquitin ligase CHIP (COOH terminus of heat shock protein 70-interacting protein), allows parkin to poly-ubiquitinate34, 35 and it is likely that other E4-like factors cooperate with parkin in vivo. Thus, parkin is a multifunctional E3-ligase, which has the capable of performing a variety of ubiquitin linkages and cellular functions.

Parkin and PD

Disease causing mutations in parkin range from single base pair substitutions to small deletions and splice site mutations, to deletions that span hundreds of thousands of nucleotides36, 37. The general view is that parkin-related PD arises from similar mechanisms. Along these lines, the simplest explanation is that parkin mutations serve to lead to a loss of parkin function. Parkin-linked PD where deletions span several exons is certainly consistent with a loss of parkin function. Nonsense-mediated decay would serve to destabilize any truncated transcripts that might be expressed leading to the absence of protein expression. Indeed, there is little evidence that truncated parkin protein is expressed in patients with exon deletions (Reviewed in West, Dawson and Dawson 38).

Many missense mutations also appear to lead to a loss of parkin function through decreased catalytic activity, aberrant ubiquitination and impairment of proteasomal degradation and/or destabilization of parkin leading to insolubility or rapid proteasomal degradation of mutant parkin34, 35, 39, 40. Thus, the general view is that disease-causing mutations in parkin lead to a loss of parkin function, albeit through different mechanisms.

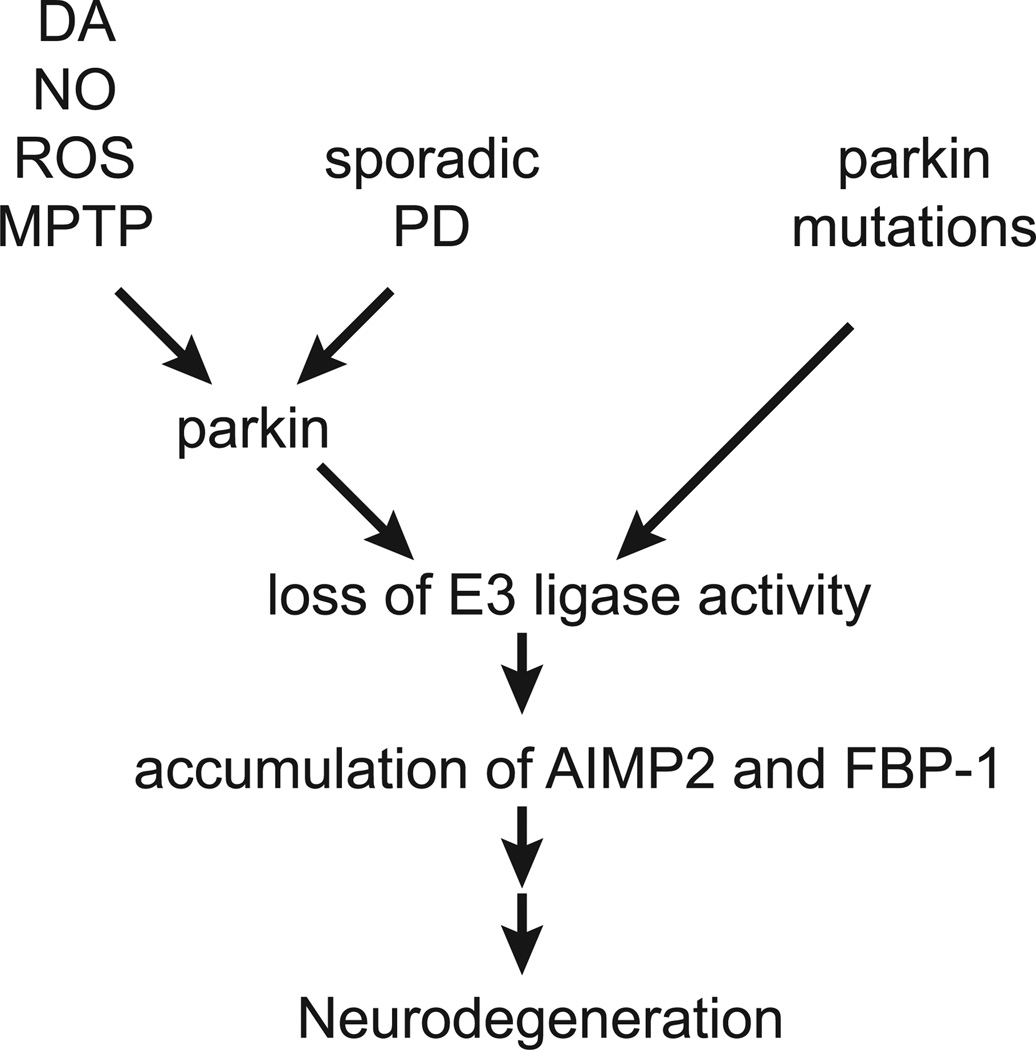

Parkin may play a role in sporadic PD through common and frequent mutations16, 18. In addition, it is inactivated due to nitrosative stress 41, 42, dopaminergic stress43 and oxidative stress44, 45, which are key pathogenic processes in sporadic PD. Thus, loss of parkin E3-ligase activity may not only play a role in AR-PD, but sporadic PD as well (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Parkin inactivation plays a role in both sporadic Parkinson’s disease (PD)and in patients with parkin mutations. Dopaminergic (DA), nitrosative (nitric oxide – NO), oxidative (reactive oxygen species – ROS) and MPTP intoxication can inactive parkin abrogating its ubiquitination and cytoprotective properties. In sporadic PD, parkin is inactivated through nitrosative and dopaminergic stress and autosomal recessive PD it is inactivated through a variety of mutations. The loss of parkin E3 ligase activity leads to the accumulation of AIMP2 and FBP1, which causes neurodegeneration through mechanisms that require further clarification.

Parkin Substrates

A number of parkin substrates have been identified and were recently reviewed by West, Dawson and Dawson38. “CDCrel-1 was the first parkin substrate identified. It belongs to a family of GTPases called septins and is robustly expressed in the nervous system where it associates with synaptic vesicles26. Adeno-associated viral mediated transduction of CDCrel-1 induces neurodegeneration46. However, there is limited evidence that CDCrel-1 accumulates in the absence of parkin and that parkin modulates CDCrel-1 levels in vivo47.

Parkin-associated endothelin receptor-like receptor (Pael-R) in another putative parkin substrate. It is a G-protein-coupled transmembrane protein with homology to the endothelin receptor type B32. Pael-R is primarily expressed in oligodendrocytes, but it is present dopaminergic neurons. Pael-R overexpression induces the unfolded stress response in cultured cells and becomes insoluble. Parkin attenuates the formation of insoluble Pael-R and its accompanying toxicity presumably through an ubiquitination dependent mechanism. Pan-neuronal Human Pael-R overexpression in Drosophila causes age-dependent selective degeneration of dopaminergic neurons lending some credibility to neurodegenerative specificity 48. However, limited evidence suggests that parkin is indeed a native physiological factor responsible for regulating levels of Pael-R.

The alpha-synuclein interacting protein, synphilin-1, interacts with and is ubiquitinated by parkin leading to the formation of protein aggregates when over-expressed with alpha-synuclein in cell culture49. Parkin preferentially mediates the formation of lysine-63 linked polyubiquitin chains onto synphilin-130. Recent studies suggest that lysine-63 mediated ubiquitination may participate in the degradation of inclusions by serving as signal for autophagic cargo when the ubiquitin proteasome system is dysfunctional 50, 51. Parkin mediated lysine-63 ubiquitination may be play an important role in this process52. Thus, parkin may play a specialized role in inclusion formation and targeting proteins for autophagic clearance when the ubiquitin-proteasome system is dysfunctional.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase interacting multifunctional protein type 2 (AIMP2), also named p38/Jtv1 was originally identified as a parkin substrate through a yeast two-hybrid screen53. AIMP2 is present in Lewy bodies. Parkin can promote the degradation of over-expressed AIMP2 presumably via polyubiquitination and proteasome degradation. Viral overexpression of AIMP2 leads to selective degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and it accumulates in parkin-null mice and in patients with parkin mutations54. Moreover, consistent with the notion that parkin is inactivated in sporadic PD, is the observation that AIMP2 also accumulates in the brains of sporadic PD. In a similar manner, the far up stream element binding protein 1 (FBP-1) accumulates in parkin knockout mice, patients with AR-PD due to parkin mutations, sporadic PD as well as the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) mouse model of Parkinson’s disease55. Parkin is inactivated in the MPTP model by S-nitrosylation41, 42. Thus, parkin substrates, such as AIMP2 and FBP-1 that are polyubiquitinated via lysine-48 chains should not only accumulate in parkin knockout mice and patients with parkin mutations, but also under conditions where parkin is inactivated such as MPTP-intoxication or sporadic PD. We propose that parkin substrates should fulfill at least these 4 criteria to be designated a true parkin substrates that are regulated by parkin-mediated ubquitination and the ubiquitin proteasomal system.

Yeast-two hybrid experiments followed by confirmation with co-immunoprecipitation and in vitro ubiquitination experiments identified a variety of other parkin substrates. Parkin interacts with α/β tubulin heterodimers and microtubules and acts to stabilize microtubule formation, potentially in an ubiquitin dependent manner56. In vitro steady-state levels of synaptotagmin XI are decreased in the presence of parkin, and protein aggregates in PD were found immunoreactive for synaptotagmin XI57. SEPT5_v2/CDCrel-2, another member of the septin family and a close homolog to CDCrel-1, has been reported as a parkin substrate and may accumulate in disease brains58. In another study, parkin was found to interact with cyclin E in the context of a protein complex including hSel-10 and Cullin-1, and found to prevent the accumulation of cyclin E in kainate acid treated neurons59. Parkin also binds to the RanBP2 protein in over-expression cell culture models and apparently influences the downstream ability of exogenous RanBP2 to sumoylate the HDAC4 protein due to ubiquitination of RanBP2 via parkin60. None of the latter substrates fulfill the criteria for a “true” parkin substrate.

A number of other functions have been attributed to parkin. Parkin monoubiquitinates HSP70, but the physiologic importance of this modification is not known 61. Parkin polyubiquitinates misfolded DJ-1 via lysine-63 chains in overexpression studies and targets misfolded DJ-1 to agggresomes via binding to HDAC6 52. Parkin-mediated monoubiquitination of the PDZ protein PICK1 regulates the activity of acid-sensing ion channels 62. Parkin reduces the cofilin-phosphorylation of LIM kinase-1 through ubiquitination 63. Both wild type and mutant ataxin-2 seems to be a substrate for parkin and ataxin-2 toxicity is attenuated by parkin overexpression 64. Parkin may also play a role in EGF receptor trafficking and PI(3) kinase signaling through interactions with the UIM protein, Eps15 29. Other parkin interactors and putative substrates have been identified 38 and their role in parkin-mediated PD is not clear.

Parkin and Neuroprotection

Parkin acts as a multipurpose protective agent when over expressed in a variety of stressful paradigms (reviewed by West, Dawson and Dawson 38). Parkin overexpression prevents mitochondrial swelling in PC-12 cells treated with ceramide or subjected to serum withdrawal 65. Kainic acid excitotoxicity is attenuated by parkin over-expression in neurons 59. Manganese-induced cell death is reduced by parkin overexpression 66 and parkin protects against dopaminergic toxicity 67. The exact mechanisms of how parkin overexpression protects against a variety of toxic insults is not known, but it seems to be dependent on its E3 ligase activity. Dopaminergic cell death was comparable between wild type and parkin null mice following MPTP or 6-OHDA intoxication 68, 69, thereby suggesting that cell line models of parkin overexpression may not recapitulate in vivo experiments.” Moreover, expression of parkin may provide a non-physiologic protection to a variety of stressors, but endogenous levels of parkin do not participate in neuronal survival to these various stressors.

α-Synuclein toxicity in rat, drosophila, and in cellular models is reduced by parkin overexpression 48, 70, 71. Parkin and α-synuclein fail to interact and cannot bind one another in most assays 49, 72. There is one report that the interaction of parkin with alpha-synuclein requires post-translation modification, but this has not been replicated 25. Thus, how parkin overexpression prevents α-synuclein toxicity is unclear. Indeed similar to exogenous stressors, parkin may be protecting against α-synuclein toxicity non-specifically. The toxicity and phenotype associated with mutant α-synuclein was not affected by the loss of parkin in a genetic cross between parkin-knockout mice and α-synuclein overexpressing mice 73. Little if any biochemical evidence suggests that loss of parkin expression influences overexpressed α-synuclein toxicity as might be assumed from studies employing the reverse context, namely overexpressing both parkin and α-synuclein. The implication is that parkin may acquire novel (perhaps non-specific) attributes when expressed at non-physiological concentrations (reviewed by West, Dawson and Dawson 38). Additional studies concerning endogenous parkin are required to understand its largely undefined role in protection against a variety of stressors including α-synuclein. More importantly is the focus on understanding how endogenous parkin functions and how it regulates the survival of dopamine neurons.

The diverse array of parkin substrates and its broad neuroprotective properties have hindered the generation of a consensus in the field on parkin’s physiologic function and pathologic role in PD. The majority of substrates are understood only by a limited number of experiments that, in general, fail to determine the effects of ubiquitination on the function of the host protein and whether the interaction has physiological relevance. The mouse parkin knockout models have not demonstrated a robust up-regulation of any protein as evident by several proteomic screens 47, 74. It is difficult to reconcile a common biochemical pathway among the interacting substrates and there is no clear pre-existing genetic or biochemical data that might elevate a particular substrate to a more important status with the possible exception of AIMP2 and FBP-1 as they accumulate in several in vivo models of parkin dysfunction (reviewed by West, Dawson and Dawson 38).

Parkin and Mitochondrial Function

Clues to the key determinant of parkin-mediated pathology may come from recent studies in drosophila. The absence of parkin in drosophila leads to mitochondrial pathology and apoptotic muscle degeneration and raises the possibility that similar mitochondrial impairment triggers the selective cell loss observed in AR-PD 75, 76. Despite having only having mild deficits, parkin knockout mice have features of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage 74 and parkin-deficient patients have decreased lymphocyte mitochondrial complex I activity 77 providing further support to the notion that loss of parkin function leads to mitochondrial deficits. How parkin might regulate mitochondrial function is not known. A small fraction of parkin may reside at or near the mitochondria 78, suggesting that parkin might regulate a mitochondrial protein that is important for mitochondrial function. However, the suitability for parkin antibodies to detect endogenous parkin raises questions about the mitochondrial localization of parkin 79. Parkin also seems to enhance mitochondrial biogenesis through as yet unconfirmed mechanisms 78. Further clues come from additional studies in drosophila. Loss of drosophila PINK1 also leads to defects in mitochondrial function resulting in male sterility, apoptotic muscle degeneration and minor loss of DA neurons mirroring the loss of drosophila parkin phenotype 80, 81. The loss-of-function PINK1 phenotype is rescued by overexpression of parkin, but the loss-of-function parkin phenotype is not rescued by PINK1 suggesting that PINK1 and parkin, at least in part, function in the same pathway and that PINK1 functions upstream 82. PINK1 deficiency in human cells also results in mitochondrial abnormalities, which is ameliorated by enhanced expression of parkin 83. The mechanism by which both parkin and PINK1 regulate mitochondrial function and integrity is not known, but the enlarged and swollen mitochondria in parkin and PINK1 deficient drosophila suggests that they regulate mitochondrial morphology 84. It is conceivable that parkin regulates the stead-state level of a protein critical for maintaining mitochondrial function. We posit that this putative parkin substrate should accumulate in models of parkin inactivation such as Parkin knockouts and the MPTP intoxication model as in AR-PD due to parkin mutations and in sporadic PD. Moreover, PINK1 should regulate its interaction or ubiquitination by parkin. Future studies are required to identify this missing link.

Conclusions

Parkin is an ubiquitin E3 ligase that plays an important role in the pathogenesis of PD. Not only does parkin play a role in AR-PD, it seems to play important roles in the pathogenesis of sporadic PD as it is inactivated in sporadic PD due to nitrosative, oxidative and dopaminergic stress. Parkin is multi-functional E3 ligase that is capable of different ubiquitin modifications including monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination via lysine-48 or lysine-63 chains. True parkin substrates that are regulated by the ubiquitin proteasome system should accumulate in both AR-PD and sporadic PD as well as animal models of parkin inactivation such as parkin knockouts and the MPTP-intoxication model. AIMP2 and FBP-1 fulfill the criteria for true parkin substrates suggesting that they may play important roles in parkin-mediated PD. Parkin appears to be a multi-functional neuroprotective protein when overexpressed, but whether it plays such a broad protective role when expressed at endogenous levels seems unclear. Finally, recent studies suggest that parkin may play important roles in mitochondrial function in a common genetic pathway that is shared by PINK1. Understanding the relationship of parkin to mitochondrial function, it relationship to PINK1 and the role of true parkin substrates in these processes will lead to a greater understanding of the normal physiologic role of parkin and its role in the pathogenesis of PD.

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH/NINDS P50 NS38377. T.M.D. is the Leonard and Madlyn Abramson Professor in Neurodegenerative Diseases.

References

- 1.Gasser T. Genetics of Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2001;248(10):833–840. doi: 10.1007/s004150170066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson TM. New animal models for Parkinson's disease. Cell. 2000;101(2):115–118. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80629-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Rare genetic mutations shed light on the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(2):145–151. doi: 10.1172/JCI17575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giasson BI, Lee VM. Parkin and the molecular pathways of Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2001;31(6):885–888. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00439-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lansbury PT, Brice A. Genetics of Parkinson's disease and biochemical studies of implicated gene products. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12(3):299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim KL, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. The genetics of Parkinson's disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2002;2(5):439–446. doi: 10.1007/s11910-002-0071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savitt JM, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease: molecules to medicine. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1744–1754. doi: 10.1172/JCI29178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polymeropoulos MH, Higgins JJ, Golbe LI, et al. Mapping of a gene for Parkinson's disease to chromosome 4q21-q23. Science. 1996;274(5290):1197–1199. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, et al. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson's disease [see comments] Science. 1997;276(5321):2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392(6676):605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonifati V, Rizzu P, van Baren MJ, et al. Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science. 2003;299(5604):256–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1077209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V, et al. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson's disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science. 2004;304(5674):1158–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1096284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paisan-Ruiz C, Jain S, Evans EW, et al. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2004;44(4):595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimprich A, Biskup S, Leitner P, et al. Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron. 2004;44(4):601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deshaies RJ, Joazeiro CA. RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:399–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein C, Lohmann K. Parkinson disease(s): is "Parkin disease" a distinct clinical entity? Neurology. 2009;72(2):106–107. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000333666.65522.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein C, Schlossmacher MG. Parkinson disease, 10 years after its genetic revolution: multiple clues to a complex disorder. Neurology. 2007;69(22):2093–2104. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271880.27321.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilcher H. Parkin implicated in sporadic Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(12):798. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(05)70237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa A, Takahashi H. Clinical and neuropathological aspects of autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. J Neurol. 1998;245(11) Suppl 3:P4–P9. doi: 10.1007/pl00007745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrer M, Chan P, Chen R, et al. Lewy bodies and parkinsonism in families with parkin mutations. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(3):293–300. doi: 10.1002/ana.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pramstaller PP, Schlossmacher MG, Jacques TS, et al. Lewy body Parkinson's disease in a large pedigree with 77 Parkin mutation carriers. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(3):411–422. doi: 10.1002/ana.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasaki S, Shirata A, Yamane K, Iwata M. Parkin-positive autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinsonism with alpha-synuclein-positive inclusions. Neurology. 2004;63(4):678–682. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134657.25904.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mori H, Kondo T, Yokochi M, et al. Pathologic and biochemical studies of juvenile parkinsonism linked to chromosome 6q. Neurology. 1998;51(3):890–892. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Warrenburg BP, Lammens M, Lucking CB, et al. Clinical and pathologic abnormalities in a family with parkinsonism and parkin gene mutations. Neurology. 2001;56(4):555–557. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimura H, Hattori N, Kubo S, et al. Familial Parkinson disease gene product, parkin, is a ubiquitin-protein ligase. Nat Genet. 2000;25(3):302–305. doi: 10.1038/77060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Gao J, Chung KK, Huang H, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Parkin functions as an E2-dependent ubiquitin- protein ligase and promotes the degradation of the synaptic vesicle-associated protein, CDCrel-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(24):13354–13359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240347797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imai Y, Soda M, Takahashi R. Parkin suppresses unfolded protein stress-induced cell death through its E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(46):35661–35664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fallon L, Belanger CM, Corera AT, et al. A regulated interaction with the UIM protein Eps15 implicates parkin in EGF receptor trafficking and PI(3)K-Akt signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(8):834–842. doi: 10.1038/ncb1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim KL, Chew KC, Tan JM, et al. Parkin mediates nonclassical, proteasomal-independent ubiquitination of synphilin-1: implications for Lewy body formation. J Neurosci. 2005;25(8):2002–2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4474-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim KL, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Parkin-mediated lysine 63-linked polyubiquitination: a link to protein inclusions formation in Parkinson's and other conformational diseases? Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27(4):524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imai Y, Soda M, Inoue H, Hattori N, Mizuno Y, Takahashi R. An unfolded putative transmembrane polypeptide, which can lead to endoplasmic reticulum stress, is a substrate of Parkin. Cell. 2001;105(7):891–902. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00407-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doss-Pepe EW, Chen L, Madura K. Alpha-synuclein and parkin contribute to the assembly of ubiquitin lysine 63-linked multiubiquitin chains. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(17):16619–16624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413591200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hampe C, Ardila-Osorio H, Fournier M, Brice A, Corti O. Biochemical analysis of Parkinson's disease-causing variants of Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase with monoubiquitylation capacity. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(13):2059–2075. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuda N, Kitami T, Suzuki T, Mizuno Y, Hattori N, Tanaka K. Diverse effects of pathogenic mutations of Parkin that catalyze multiple monoubiquitylation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(6):3204–3209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West AB, Maidment NT. Genetics of parkin-linked disease. Hum Genet. 2004;114(4):327–336. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West AB, Moore DJ, Choi C, et al. Parkinson's disease-associated mutations in LRRK2 link enhanced GTP-binding and kinase activities to neuronal toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(2):223–232. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.West AB, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. The Role of Parkin in Parkinson's Disease. In: Dawson TM, editor. Parkinson's Disease: Genetics and Pathogenesis: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc. 2007. pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang C, Tan JM, Ho MW, et al. Alterations in the solubility and intracellular localization of parkin by several familial Parkinson's disease-linked point mutations. J Neurochem. 2005;93(2):422–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winklhofer KF, Henn IH, Kay-Jackson PC, Heller U, Tatzelt J. Inactivation of parkin by oxidative stress and C-terminal truncations: a protective role of molecular chaperones. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(47):47199–47208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306769200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung KK, Thomas B, Li X, et al. S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates ubiquitination and compromises parkin's protective function. Science. 2004;304(5675):1328–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.1093891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao D, Gu Z, Nakamura T, et al. Nitrosative stress linked to sporadic Parkinson's disease: S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(29):10810–10814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404161101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LaVoie MJ, Ostaszewski BL, Weihofen A, Schlossmacher MG, Selkoe DJ. Dopamine covalently modifies and functionally inactivates parkin. Nat Med. 2005;11(11):1214–1221. doi: 10.1038/nm1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang C, Ko HS, Thomas B, et al. Stress-induced alterations in parkin solubility promote parkin aggregation and compromise parkin's protective function. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(24):3885–3897. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong ES, Tan JM, Wang C, et al. Relative sensitivity of parkin and other cysteine-containing enzymes to stress-induced solubility alterations. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(16):12310–12318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong Z, Ferger B, Paterna JC, et al. Dopamine-dependent neurodegeneration in rats induced by viral vector-mediated overexpression of the parkin target protein, CDCrel-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(21):12438–12443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2132992100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Periquet M, Corti O, Jacquier S, Brice A. Proteomic analysis of parkin knockout mice: alterations in energy metabolism, protein handling and synaptic function. J Neurochem. 2005;95(5):1259–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Y, Nishimura I, Imai Y, Takahashi R, Lu B. Parkin suppresses dopaminergic neuron-selective neurotoxicity induced by Pael-R in Drosophila. Neuron. 2003;37(6):911–924. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chung KK, Zhang Y, Lim KL, et al. Parkin ubiquitinates the alpha-synuclein-interacting protein, synphilin-1: implications for Lewy-body formation in Parkinson disease. Nat Med. 2001;7(10):1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan JM, Wong ES, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Lim KL. Lysine 63-linked polyubiquitin potentially partners with p62 to promote the clearance of protein inclusions by autophagy. Autophagy. 2007;4(2) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan JM, Wong ES, Kirkpatrick DS, et al. Lysine 63-linked ubiquitination promotes the formation and autophagic clearance of protein inclusions associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(3):431–439. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olzmann JA, Li L, Chudaev MV, et al. Parkin-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination targets misfolded DJ-1 to aggresomes via binding to HDAC6. J Cell Biol. 2007;178(6):1025–1038. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corti O, Hampe C, Koutnikova H, et al. The p38 subunit of the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complex is a Parkin substrate: linking protein biosynthesis and neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(12):1427–1437. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ko HS, von Coelln R, Sriram SR, et al. Accumulation of the authentic parkin substrate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase cofactor, p38/JTV-1, leads to catecholaminergic cell death. J Neurosci. 2005;25(35):7968–7978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2172-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ko HS, Kim SW, Sriram SR, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Identification of far upstream element-binding protein-1 as an authentic Parkin substrate. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(24):16193–16196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang F, Jiang Q, Zhao J, Ren Y, Sutton MD, Feng J. Parkin stabilizes microtubules through strong binding mediated by three independent domains. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(17):17154–17162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500843200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huynh DP, Scoles DR, Nguyen D, Pulst SM. The autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinson disease gene product, parkin, interacts with and ubiquitinates synaptotagmin XI. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(20):2587–2597. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choi P, Snyder H, Petrucelli L, et al. SEPT5_v2 is a parkin-binding protein. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;117(2):179–189. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Staropoli JF, McDermott C, Martinat C, Schulman B, Demireva E, Abeliovich A. Parkin is a component of an SCF-like ubiquitin ligase complex and protects postmitotic neurons from kainate excitotoxicity. Neuron. 2003;37(5):735–749. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Um JW, Min DS, Rhim H, Kim J, Paik SR, Chung KC. Parkin ubiquitinates and promotes the degradation of RanBP2. J Biol Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moore DJ, West AB, Dikeman DA, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Parkin Mediates the Degradation-Independent Ubiquitination of Hsp70. J Neurochem. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Joch M, Ase AR, Chen CX, et al. Parkin-mediated monoubiquitination of the PDZ protein PICK1 regulates the activity of acid-sensing ion channels. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(8):3105–3118. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lim MK, Kawamura T, Ohsawa Y, et al. Parkin interacts with LIM Kinase 1 and reduces its cofilin-phosphorylation activity via ubiquitination. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313(13):2858–2874. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huynh DP, Nguyen DT, Pulst-Korenberg JB, Brice A, Pulst SM. Parkin is an E3 ubiquitin-ligase for normal and mutant ataxin-2 and prevents ataxin-2-induced cell death. Exp Neurol. 2007;203(2):531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Darios F, Corti O, Lucking CB, et al. Parkin prevents mitochondrial swelling and cytochrome c release in mitochondria-dependent cell death. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(5):517–526. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Higashi Y, Asanuma M, Miyazaki I, Hattori N, Mizuno Y, Ogawa N. Parkin attenuates manganese-induced dopaminergic cell death. J Neurochem. 2004;89(6):1490–1497. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jiang H, Ren Y, Zhao J, Feng J. Parkin protects human dopaminergic neuroblastoma cells against dopamine-induced apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(16):1745–1754. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perez FA, Curtis WR, Palmiter RD. Parkin-deficient mice are not more sensitive to 6-hydroxydopamine or methamphetamine neurotoxicity. BMC Neurosci. 2005;6:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-6-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomas B, von Coelln R, Mandir AS, et al. MPTP and DSP-4 susceptibility of substantia nigra and locus coeruleus catecholaminergic neurons in mice is independent of parkin activity. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26(2):312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Petrucelli L, O'Farrell C, Lockhart PJ, et al. Parkin protects against the toxicity associated with mutant alpha-synuclein: proteasome dysfunction selectively affects catecholaminergic neurons. Neuron. 2002;36(6):1007–1019. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamada M, Mizuno Y, Mochizuki H. Parkin gene therapy for alpha-synucleinopathy: a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16(2):262–270. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liani E, Eyal A, Avraham E, et al. Ubiquitylation of synphilin-1 and alpha-synuclein by SIAH and its presence in cellular inclusions and Lewy bodies imply a role in Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(15):5500–5505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401081101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.von Coelln R, Thomas B, Andrabi SA, et al. Inclusion body formation and neurodegeneration are parkin independent in a mouse model of alpha-synucleinopathy. J Neurosci. 2006;26(14):3685–3696. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0414-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Palacino JJ, Sagi D, Goldberg MS, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in parkin-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(18):18614–18622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Greene JC, Whitworth AJ, Kuo I, Andrews LA, Feany MB, Pallanck LJ. Mitochondrial pathology and apoptotic muscle degeneration in Drosophila parkin mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(7):4078–4083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737556100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pesah Y, Pham T, Burgess H, et al. Drosophila parkin mutants have decreased mass and cell size and increased sensitivity to oxygen radical stress. Development. 2004;131(9):2183–2194. doi: 10.1242/dev.01095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Muftuoglu M, Elibol B, Dalmizrak O, et al. Mitochondrial complex I and IV activities in leukocytes from patients with parkin mutations. Mov Disord. 2004;19(5):544–548. doi: 10.1002/mds.10695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kuroda Y, Mitsui T, Kunishige M, et al. Parkin enhances mitochondrial biogenesis in proliferating cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(6):883–895. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pawlyk AC, Giasson BI, Sampathu DM, et al. Novel monoclonal antibodies demonstrate biochemical variation of brain parkin with age. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(48):48120–48128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306889200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Park J, Lee SB, Lee S, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Drosophila PINK1 mutants is complemented by parkin. Nature. 2006;441(7097):1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/nature04788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Clark IE, Dodson MW, Jiang C, et al. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature. 2006;441(7097):1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tan JM, Dawson TM. Parkin blushed by PINK1. Neuron. 2006;50(4):527–529. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Exner N, Treske B, Paquet D, et al. Loss-of-function of human PINK1 results in mitochondrial pathology and can be rescued by parkin. J Neurosci. 2007;27(45):12413–12418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0719-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Poole AC, Thomas RE, Andrews LA, McBride HM, Whitworth AJ, Pallanck LJ. The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(5):1638–1643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709336105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]