Abstract

Background:

Dysmenorrhea has negative effects on women's life. Due to side-effects of chemical drugs, there is growing trend toward herbal medicine. The aim of this study was to assess the effect of Dill compared to mefenamic acid on primary dysmenorrhea.

Materials and Methods:

This double-blind, randomized, clinical trial study was conducted on 75 single female students between 18 and 28 years old educating in Nursing and Midwifery School and Paramedical Faculty of Qom University of Medical Sciences of Iran in 2011. They were allocated randomly into one of the three groups: In Dill group, they took 1000 mg of Dill powder q12h for 5 days from 2 days before the beginning of menstruation for two cycles. Other groups received 250 mg mefenamic acid or 500 mg starch capsule as placebo, respectively. Dysmenorrhea severity was determined by a verbal multidimensional scoring system and a visual analog scale (VAS). Students with mild dysmenorrhea were excluded. Data were analyzed by SPSS using the descriptive statistic, paired-samples t-test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Mann-Whitney test, and Kruskal-Wallis test.

Results:

There were no significant differences between three groups for demographic or descriptive variables. Comprising the VAS showed that the participants of Dill and mefenamic acid groups had lower significant pain in the 1st and the 2nd months after treatment, whereas in the placebo group this was only significant in the 2nd month (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Dill was as effective as mefenamic acid in reducing the pain severity in primary dysmenorrhea. Further studies regarding side-effects of Dill and its interactivity are recommended.

Keywords: Dill (Anethum graveolens), dysmenorrhea, mefenamic acid, pain, placebo

INTRODUCTION

Dysmenorrhea or painful menstruation is one of the most common gynecological problems[1] that involves about 50-70% of women during their reproductive life.[2] Its prevalence rate varies between 50% and 90% in different societies and in Iran was reported as many as 74-86.1%.[3] Primary dysmenorrhea is known as menstrual pain without pelvic disease, whereas secondary dysmenorrhea is associated with various pelvic causes.

Primary dysmenorrhea usually occurs during 1-2 years after the menarche.[4] Although the etiology of primary dysmenorrhea is not completely known, it is introduced that prostaglandins (PGs) originating in secretory endometrium causes myometrial contractions.[5] The excessive or imbalanced prostanoids of endometer increases the dysrhythmic uterine contractions and basic muscle tone and active pressure that these conditions decrease the uterine blood flow and increase the sensitivity of peripheral nerves and cause pain.[6,7] According to hypotheses, the women with dysmenorrhea have more activity of cyclooxygenase and prostanoid synthase enzymes. This provides the base of the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as inhibitors of cyclooxygenase enzymein treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.[4,8] However, NSAIDs have different side-effects. For example, various gastrointestinal adverse effects such as nausea, diarrhea, dyspepsia, and also fatigue are reported with taking mefenamic acid.[9,10] Moreover, in some conditions such as gastrointestinal ulcers and bronchial hypersensitivity to aspirin, taking them is contraindicated.[10] On the other hand, according to the results of some studies, 20-25% of women do not respond to current medicine.[11,12] These problems lead to withdrawing of the chemical treatment and or using the gastric drugs. Consequently, they increasingly appeal to other treatments such as herbal medicine. The suppressive effects of some herbal drugs such as Dang-Qui-Shao-Yao-san, chamomile tea, Feonicurum vulgare, etc. on uterine contractions and their pain–relief effects on dysmenorrhea have been reported in some studies.[13,14,15,16]

Anethum graveolens (Dill), from Apiaceae family, is a traditional herb that has various medical indications worldwide.[17] It is cultivated in the most areas of the world and also widely in Khozestan, Khorasan, and Eastern Azerbaijan provinces of Iran.[18] It is a 1 year plant with 30-100 cm length. Its fruit essence consists of carveol, d-Carvone, d-hydrocarveol, dihydrocarvone, limonene, carvacrol thymol, etc.[19] its seeds have 3-3.5% essential oil and are used for treatment of stomach illnesses, food digestion, stopping hiccup, flowing of milk in nursing mothers, relieving of pain and as anticonvulsant and antivomiting.[18] We found no controlled research of effect of Dill in primary dysmenorrhea. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of Dill seeds on pain severity of primary dysmenorrhea and to compare it with mefenamic acid and placebo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After initial approving by the vice chancellor for research of Qom University of Medical Sciences, complete explanations were given to the participants and informed consent form was taken. This double-blind, randomized study was conducted among 75 female students between 18 and 28 years old. Entry criteria were being single and educating in Nursing and Midwifery School and Paramedical Faculty of Qom University of Medical Sciences in 2011 (Qom city is almost situated in the center of Iran with about 150 km2 distance from Tehran [metropolis of Iran]). In the beginning of the study, a complete history was taken and the secondary dysmenorrhea was ruled out. Patients with the history of pelvic or organic disorders, any known gastrointestinal or urogenital or hematological or other systems disorders, irregularity of menstrual cycles, taking any drug, and previous sensitivity to NSAIDs or Dill and or mild dysmenorrheal were not included.

The participants were allocated randomly into one of the following groups: In the first group, the patients were treated by Dill capsules containing 500 mg of powder of Dill seed in which two capsules orally q12h (totally 1000 mg q12h) and in the second group by 250 mg mefenamic acid capsule orally q12h and in the third group by starch as placebo (the same company) 500 mg q12h, since 2 days before the beginning of their menstruation for 5 days. All of the capsules were made by Boo Ali Research Center of Qom city and were completely similar in shape. In regarding the blinding process, the researchers and the participants were uninformed of allocating manner of each group and a third one that did not involve in analyzing and interpreting, etc., allocated the participants in groups and allotted a code number to everyone. The capsules were been delivered to the subjects 1-week before beginning the menstruation bleeding and during the study. The researchers were following the participants throughout the study in view of regular taking the capsules. The subjects were followed for two cycles (2 months) and were asked to answer to the questionnaires at the end of every cycle.

The participants filled a two part questionnaire at the beginning of study, including demographic characteristics in the first part (such as age, height, weight, etc.) and menstrual characteristics in the second part (such as menarche age, duration of menses, interval of cycles, etc.).[11] The severity of dysmenorrhea was assessed by a verbal multidimensional scoring (VMS) system and by a visual analog scale (VAS). VMS that has been used in various previous studies[11,20] has four grades:

Grade 0: Menstruation with no influence on daily activities or use of analgesics

Grade 1: Menstruation with mild pain but rare influence on daily activities or use of analgesics

Grade 2: Menstruation with moderate pain with influence on daily activities and perpetuity need to analgesics,

Grade 3: Menstruation with severe pain with significant limitations on daily activities and ineffective use of analgesics and vegetative symptoms as headache, nausea, vomiting, tiredness, and diarrhea.[11,20]

According to the 10-point VAS, mild dysmenorrhea was defined as score of 0-3, moderate as score of 4-7 and severe as score of 8-10.[21] Women with mild dysmenorrhea (score of 0-3) were excluded from this study.[11] They also answered to the questionnaires at the end of the first and the 2nd months of treatment. These questionnaires had questions about changes of the menstrual cycle due to taking capsules or special events, etc.

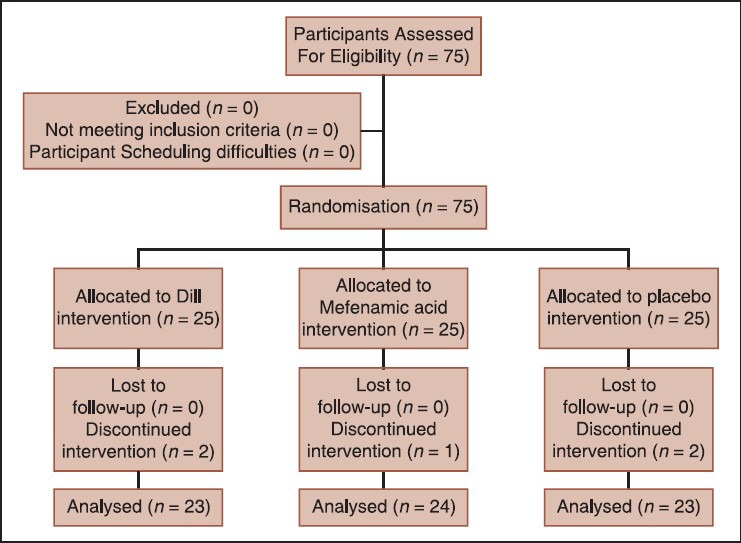

Of 75 participants of this study, five of them did not continue the study due to fearing of its side-effects; therefore we evaluated 70 students [Figure 1]. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and frequencies. Severity of pain was compared within groups with paired-samples t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test and between groups with Mann-Whitney test and Kruskal-Wallis test in SPSS 18 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Patients progress through the trial: Consolidated standards of reporting trials flowchart

Ethical considerations

The vice chancellor of Qom University of Medical Sciences approved the study. At beginning, complete information about this study was given to the participants then informed consents of randomized-controlled trial studies were taken from them. Students were ensured of being secret their answers. This research project is registered in IRCT with No. 201110205543N2.

RESULTS

Of 75 participants of this study, five of them did not continue the study; therefore finally, seventy students were analyzed: 23 students in Dill group, 23 in the placebo group and 24 in mefenamic acid group.

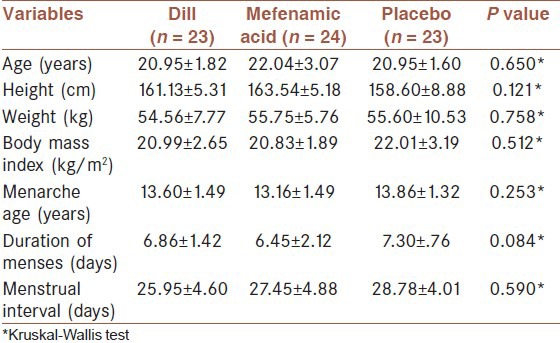

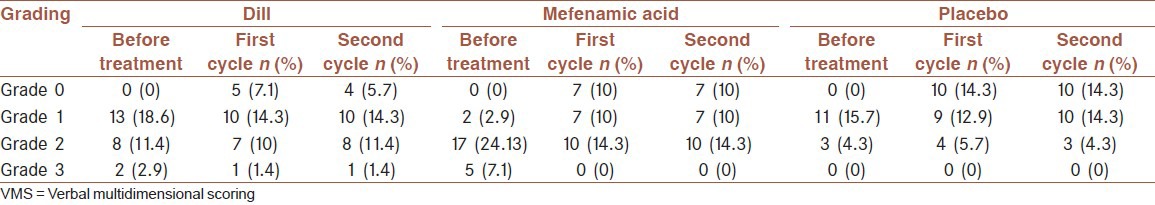

The mean age of the participants was 21.32 ± 2.3 years (ranging between 19 and 23 years). Characteristics of students are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference between three groups for demographic or descriptive variables. Comparison of pain severity in the three groups before and after treatment showed that before treatment, 2.9% of participants of Group 1 (Dill) and 7.1% of Group 2 (mefenamic acid) were complaint of menstruation with severe pain with significant limitations on daily activities that was not responding to analgesics, but after treatment, this rate reached to 1.4% and 0%, respectively in this two groups [Table 2].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants

Table 2.

Severity of dysmenorrhea assessed by VMS in three groups of study before and after treatment

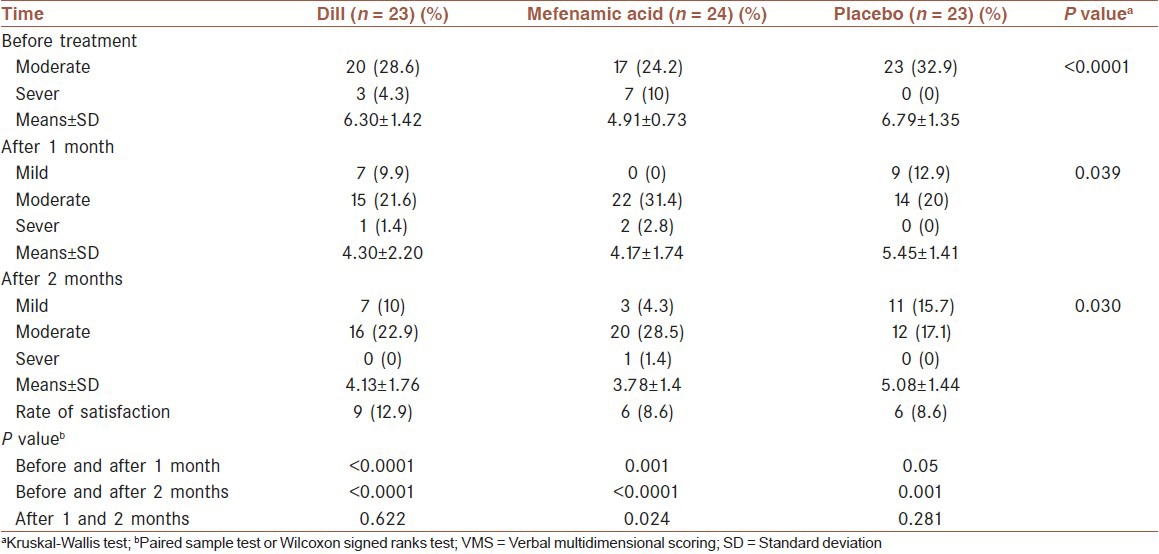

In comparison of VAS, before and after treatment, paired-sample t-test showed that in Group 1 (Dill), the subjects had lower significant pain in the 1st and the 2nd months after treatment than before it (P < 0.0001). In Group 2 (mefenamic acid), also Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that also participants had lower significant pain in the first (P = 0.001) and the 2nd months (P < 0.0001) than before treatment. In Group 3 (placebo) paired-sample t-test showed that this difference was nonsignificant in the 1st month (P = 0.05), but it was significant in the 2nd month than before treating (P = 0.001). In comparison of effect of Dill and mefenamic acid on decreasing the severity of primary dysmenorrhea, Mann–Whitney test showed no significant difference in the 1st and 2nd months after treatment (P > 0.05) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Severity of dysmenorrhea assessed by the VAS before and after treatment

In assessing the side-effects, in Dill group, two students reported menstrual changes as increasing in amount and duration of bleeding and one student reported gastrointestinal discomfort. In mefenamic acid group, menstrual changes and gastrointestinal discomfort were reported in one and two students, respectively. In placebo group, each of the mentioned side-effects was only observed in one student. These differences between three groups were statistically nonsignificant (P = 0.621).

DISCUSSION

In this double-blind randomized study, it was demonstrated that Dill can be as effective as mefenamic acid in decreasing the pain severity of primary dysmenorrhea. The results are in agreement with the results of Mohammadinia et al.[22] Furthermore, Our findings are similar to those of Gharib Naseri et al. that investigated the effects of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 mg/kg of Dill fruit hydroalcoholic extract (DFHE) on virgin rat uterus contractions induced by KCl (60 mM) and oxytocin (10 mU/m1).[19] In their study, in the presence of calcium, DFHE increased contractions, but in the absence of calcium, the contractions induced by oxytocin was weaker than KCL. Furthermore, Garib Naseri and Heidari explored the effects of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg DFHE on rat ileum contractions and found that DFHE has dose-dependently spasmolytic effect on the KCl-, acetylcholine and BaCl2 -induced contractions of ileum.[23] Also, our study results are in agreement with those of Iravani that found that branches of thyme such as Dill can decrease the severity of dysmenorrhea due to having tannin.[24]

One of the main mechanisms of dysmenorrhea is increasing the production of PGs (mainly PGF2α) in the endometrium that resulted in myometrial contractions and primary dysmenorrhea.[5,11] Anti-PGs such as NSAIDs can inhibit cyclooxygenase two and therefore PGs synthesis and relieve primary dysmenorrhea pain.[11,25] According to the conducted studies, Dill seeds have two main compounds include tannin and anethol that have sedative effects while increase the uterus contractions during and after child-bearing.[26,27,28] Anethol that is the main compound of essential oils of many herbal plants is used in the curing of anxiety, gastrointestinal comforts, and different pains.[28] Anethol in low dose, causes vasospasm through opening the voltage-dependent calcium channels but in high dose, relaxes the blood vessels.[29] Gharib Naseri et al. believe that the relaxant effect of Dill on uterus contractions is due to closing the voltage-dependent calcium channels and also, indirectly, due to calcium-releasing disorders from intracellular pool.[19] it is suggested that α- and B-adrenoceptors, opioid receptors and no production are not involved in this inhibitory effect of DFHE on contractions.[23] However, our findings do not support those of some studies.[26,30,31] Ishikawa et al. and Mahdavian et al. found that aqueous extract of Dill fruit decreases postpartum hemorrhage through increasing the uterus contractions.[26,30] Furthermore, Mansouri et al. found that the extract of Dill fruit induces the labor pains.[31] one possible explanation for these discrepancy is that the current study is done on nonpregnant uterus. Another possibility is that the compositions of seed and fruit of Dill are different. Hence, the accurate determination of the mechanisms needs to separate the constituent elements.

In view of side-effects, menstrual changes as increasing in amount and duration of bleeding and gastrointestinal discomfort were nonsignificantly reported in Dill group. Mohammadinia et al. also in comparing the effect of Anethum gravolens with mefenamic acid consumption on treatment of primary dysmenorrhea in students of Iranshahr reported nausea and dizziness in 6 students that were taken Dill.[22]

Mahdavian et al. (2001) in an investigation of effectiveness of oral Dill extracts on postpartum hemorrhage reported no side-effects in Dill recipients.[26]

We did not explore in this study the interactivity of Dill capsules with other drugs especially with NSAIDs and also its effects on other signs and symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea, so further research is recommended to assess them. Furthermore, because of all the participants were single, we did no pelvic examination for rule out organic pelvic disease and secondary dysmenorrhea. Hence, we were contented only to their history (age of beginning dysmenorrhea, history of lack of related disease, etc.).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This project was funded by Qom University of Medical Sciences (Iran). The authors hereby acknowledge the research deputy of Qom University of Medical Sciences and all who helped us in this research, especially all the students who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study is funded by Vice Chancellor for Education & Research of Qom (No: 90211), University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.French L. Dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:285–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott J. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2003. Danforth's Obstetrics and Gynecology; p. 523. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Namavar Jahromi B, Tartifizadeh A, Khabnadideh S. Comparison of fennel and mefenamic acid for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;80:153–7. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berek JS. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2012. Berek & Novak's Gynecology; p. 484. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Speroff L, Fritz MA. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility; pp. 539–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawood MY. Primary dysmenorrhea: Advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:428–41. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000230214.26638.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jabbour HN, Sales KJ. Prostaglandin receptor signalling and function in human endometrial pathology. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doty E, Attaran M. Managing primary dysmenorrhea. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19:341–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safari A, Shah Rezaei GH, Damavandi A. Comparison of the effects of vitamin E and mefenamic acid on the severity of primary dysmenorrheal. J Army Univ Med Sci. 2006;4:735–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proctor ML, Roberts H, Farquhar CM. Combined oral contraceptive pill (OCP) as treatment for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD002120. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002120.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozgoli G, Goli M, Moattar F. Comparison of effects of ginger, mefenamic acid, and ibuprofen on pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:129–32. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proctor ML, Murphy PA. Herbal and dietary therapies for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;3:CD002124. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu CS, Yang JK, Yang LL. Effect of a dysmenorrhea Chinese medicinal prescription on uterus contractility in vitro. Phytother Res. 2003;17:778–83. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu CS, Yang JK, Yang LL. Effect of “Dang-Qui-Shao-Yao-San” a Chinese medicinal prescription for dysmenorrhea on uterus contractility in vitro. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenabi E, Ebrahimzade S. Chamomile tea for relief of primary dysmenorrheal. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2010;13:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torkzahrani S, Mojab F, Akhavan Amjadi M, Alavi Majd H. Clinical effects of Feonicurum vulgare extract on primary dysmenorrheal. J Reprod Infertil. 2007;8:45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davazdah Emami S, Jahansooz MR, Sefidkon F, Mazaheri D. Comparison of planting season effect on agronomic characters and yield of Dill. J Crops Improv. 2010;12:41–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zargari A. Tehran, Iran: Tehran University Publication; 1996. Medicinal Plants; pp. 528–31. In Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gharib Naseri MK, Mard SA, Farboud Y. Effect of Anethum graveolens extract on rat uterus contractions. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2005;8:263–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindh I, Ellström AA, Milsom I. The effect of combined oral contraceptives and age on dysmenorrhoea: An epidemiological study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:676–82. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doulatian M, Mirabi P, Mojab F, Majd HA. Effects of Valeriana officinalis on the severity of dysmenorrheal symptoms. J Reprod Infertil. 2010;10:253–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammadinia N, Rezaei M, Salehian T, Dashipoor A. Comparing the effect of Anethum gravolens with mefenamic acid consumption on treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2013;15:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gharib Naseri MK, Heidari A. Spasmolytic effect of Anethum graveolens (Dill) fruit extract on rat ileum. Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;10:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iravani M. Study of trial effects thymus vulgaris on first dysmenorrhea. J Herb Med. 2009;30:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chantler I, Mitchell D, Fuller A. The effect of three cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors on intensity of primary dysmenorrheic pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:39–44. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318156dafc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahdavian M, Golmakani N, Mansoori A, Hosseinzade H, Afzalaghaee M. An investigation of effectiveness of oral Dill extracts on postpartum hemorrhage. J Women Midwifery Infertil Iran. 2001;7-8:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hekmatzade SF, Mirmolaei ST, Hosseini N. The effect of boiled dill (Anethum graveolens) seeds on the long active phase and labor pain intensity. Armaghane-Danesh. 2012;17:50–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts L, Gulliver B, Fisher J, Cloyes KG. The coping with labor algorithm: An alternate pain assessment tool for the laboring woman. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55:107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soares PM, Lima RF, de Freitas Pires A, Souza EP, Assreuy AM, Criddle DN. Effects of anethole and structural analogues on the contractility of rat isolated aorta: Involvement of voltage-dependent Ca2−+ channels. Life Sci. 2007;81:1085–93. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishikawa T, Kudo M, Kitajima J. Water-soluble constituents of Dill. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2002;50:501–7. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mansouri A, Pourjavad M, Hosseinzadeh H, Tarahomy M. Effect of dill extract on the uterus of pregnantmice. 3 rd International Congress of Health and Natural Products. Mashhad. 2004:64. [Google Scholar]