Abstract

The midbrain dopaminergic perikarya are differentially affected in Parkinson’s disease (PD). This study compared the effects of a partial unilateral intrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) lesion model of PD on the number, morphology, and nucleolar volume of dopaminergic cells in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), ventral tegmental area (VTA), and retrorubral field (RRF). Adult, male rats (n=10) underwent unilateral intrastriatal infusion of 6-OHDA (12.5 μg). Lesions were verified by amphetamine-stimulated rotation 7 days post-infusion. Rats were euthanized 14 days after treatment with 6-OHDA and brains were stained with a tyrosine hydroxylase-silver nucleolar (TH-AgNOR) stain. Dopaminergic cell number and morphology in the lesioned and intact hemispheres were quantified using stereological methods. The magnitude of decrease in planimetric volume, neuronal number, cell density, and neuronal volume resulting from 6-OHDA lesion differed between regions, with the SNpc exhibiting the greatest loss of neurons (46%), but the smallest decrease in neuronal volume (13%). The lesion also resulted in a decrease in nucleolar volume that was similar in all three regions (22–26%). These findings indicate that intrastriatal 6-OHDA lesion differentially affects dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc, VTA, and RRF; however, the resulting changes in nucleolar morphology suggest a similar cellular response to the toxin in all three cell populations.

Keywords: 6-hydroxydopamine, dopamine, stereology, substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area, retrorubral field

1. Introduction

The 6-hydroxydopamine lesion is a well-established animal model of Parkinson’s disease (PD), a chronic progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by loss of dopamine neurons (Kostrzewa and Jacobowitz, 1974). Although the loss of neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc, A9) is primarily responsible for the hallmark motor signs of basal ganglia dysfunction that occur in PD, such as tremor, bradykinesia, and rigidity, other midbrain dopaminergic cell populations are decreased as well. These include neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA, A10) and retrorubral field (RRF, A8), areas which may contribute to prodromal non-motor PD symptoms such as depression, sleep disturbances and anosmia. These symptoms can manifest years before the onset of motor signs, suggesting that functional changes to the VTA and RRF neurons could serve as a sentinel for future onset of PD (Becker et al., 2002; Claassen et al., 2010). The SNpc, VTA, and RRF are differentially affected in PD as well as in animal models (Deutch et al., 1986; German et al., 1989; German et al., 1992; German and Manaye, 1993; Hirsch et al., 1989; Rodríguez et al., 2001), although the reasons underlying the differential susceptibility of these regions are still unclear.

Understanding the patterns of neurodegeneration that may be occurring in early PD may elucidate the anatomical basis for the early non-motor signs of the disease. Accordingly, this study sought to determine and compare the changes in dopaminergic cell number and morphology, and nucleolar morphology, in the SNpc, VTA, and RRF using the partial unilateral intrastriatal 6-OHDA model. The partial unilateral lesion results in a moderate loss of midbrain dopamine neurons compared to more extensive lesions (Kirik et al., 1998), and is thus relevant to early-stage PD. Using this model, we have demonstrated decreased SNpc neuronal number and neuronal volume (Healy-Stoffel et al., 2012), as well as decreased volume of the nucleolus in SNpc dopaminergic cells (Healy-Stoffel et al., 2013). The nucleolus, the site of rRNA synthesis, is of particular interest as it is involved in directing the cellular response to stress (Boulon et al., 2010), and is thus a likely participant in the neurodegenerative processes in PD. Altered nucleolar size and nucleolar damage have been observed postmortem in PD as well as in several other neurodegenerative diseases (Hetman and Pietrzak, 2012; Mann and Yates, 1982; Rieker et al., 2011). Accordingly, this study extends those findings and demonstrates that intrastriatal partial 6-OHDA lesion results in loss of neurons in the VTA and RRF, as well as in the SNpc; however, the SNpc exhibited the greatest decrease in cell number and the smallest decrease in neuronal volume. The effect of the lesion on nucleolar volume was similar in all three regions.

2. Results

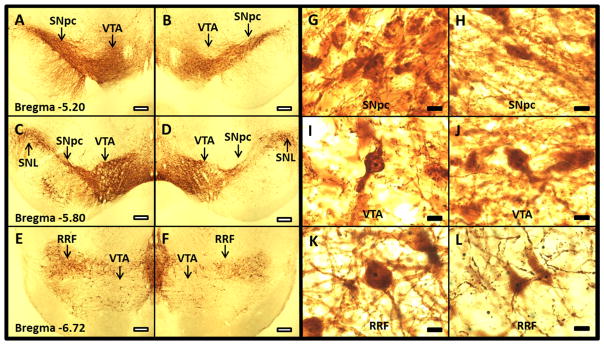

Low-and high-power photomicrographs show the morphology of the ipsilateral and contralateral SNpc, VTA and RRF TH-AgNOR-stained neurons. Low (4X) magnification demonstrates the loss of TH-positive neurons following 6-OHDA-induced neurodegeneration (Figure 1A–F). High-power (100X) magnification (Figure 1G–L) shows the outlines of nucleolar bodies within neurons in the SNpc, VTA and RRF. The nucleoli are heavily pigmented with the AgNOR stain compared to the surrounding cytoplasm. Quantitative data are summarized in Table 1. The stereological parameters used and the estimates of neuron numbers in individual rats are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1. Low- (A–F) and high-power (G–L) micrographs of TH-AgNOR stained sections of contralateral and ipsilateral SNpc, VTA and RRF.

4X images of TH-AgNOR-stained sections of contralateral and ipsilateral SN qualitatively show depletion of the contralateral SNpc (A and C), ipsilateral SNpc (B and D), contralateral VTA (A, C and E), ipsilateral VTA (B, D and F), contralateral RRF (E) and ipsilateral RRF (F). Size bar = 300 μm. 100X images show the outlines of the neurons and the AgNOR-stained nucleoli in contralateral SNpc (G), ipsilateral SNpc (H), contralateral VTA (I), ipsilateral VTA (J), contralateral RRF (K) and ipsilateral RRF (L). Representative sections from the same rat are shown. Size bar = 10 μm. Abbreviations: SNL- substantia nigra lateralis, SNpc- substantia nigra pars compacta, VTA- ventral tegmental area, RRF- retrorubral field

Table 1.

Effects of unilateral intrastriatal 6-OHDA lesion on neurons and nucleoli in the SNpc, VTA and RRF.

| Region | Contralateral | Ipsilateral | Within-subject % difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planimetric (Regional) Volume (mm3) | |||

| SNpc | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.2* | −20 ± 3 |

| VTA | 9.8 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 0.5* | −8 ± 2# |

| RRF | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.3* | −20 ± 5† |

| TH-AgNOR+ Neuronal Number | |||

| SNpc | 10,833 ± 1,042 | 5,546 ± 614* | −46 ± 6 |

| VTA | 16,641 ± 567 | 11,928 ± 449* | −28 ± 3§ |

| RRF | 3,032 ± 321 | 1,968 ± 204* | −28 ± 11§ |

| Cell Density (per mm3) | |||

| SNpc | 2,491 ± 193 | 1,609 ± 142* | −33 ± 6 |

| VTA | 1,724 ± 81 | 1,337 ± 53* | −22 ± 3 |

| RRF | 679 ± 56 | 570 ± 52 | −11 ± 10#† |

| TH-AgNOR+ Neuronal Volume (μm3) | |||

| SNpc | 3,735 ± 82 | 3,256 ± 175* | −13 ± 4 |

| VTA | 2,628 ± 101 | 2,075 ± 139* | −21 ± 5§ |

| RRF | 4,125 ± 163 | 3,104 ± 152* | −24 ± 4§ |

| TH-AgNOR+ Nucleolar Volume (μm3) | |||

| SNpc | 25 ± 1 | 20 ± 1* | −22 ± 3 |

| VTA | 21 ± 2 | 15 ± 1* | −24 ± 6 |

| RRF | 23 ± 1 | 17 ± 1* | −26 ± 4 |

Data are presented at the mean ± SEM (n = 10).

SNpc – substantia nigra pars compacta, VTA – ventral tegmental area, RRF – retrorubral field

P<0.05 vs. contralateral side by paired t-test.

P<0.05 vs. SNpc by repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test.

P<0.05 vs. SNpc by nonparametric repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

P<0.05 vs. VTA by repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test.

Planimetric (regional) volume was decreased on the side ipsilateral to the 6-OHDA injection compared to the contralateral side of the SNpc (−20%), VTA (−8%), and RRF (−20%) (P<0.05). The decreases in planimetric volume in the SNpc and RRF were roughly twice that observed in the VTA (P<0.05).

The number of AgNOR-positive neurons in all three regions was decreased on the ipsilateral side compared to the contralateral side (P<0.05). The percent decrease in TH-AgNOR-positive neuron number was roughly 60% greater in the SNpc, which exhibited a 46% decrease in neuronal number, than in the VTA and RRF, where neuronal number was decreased 28% in both regions (P<0.05).

The density of TH-AgNOR-positive neurons was decreased on the ipsilateral side compared to the contralateral side in the SNpc (−33%) and VTA (−22%) (P<0.05). The magnitude of the effect was not significantly different between these regions. In the RRF, there was no significant effect of 6-OHDA lesion on the density of AgNOR-positive neurons.

The cell body volume of TH-AgNOR-stained neurons was decreased on the ipsilateral side compared to the contralateral side in the SNpc (−13%), VTA (−21%), and RRF (−24%) (P<0.05). The decrease in cell volume was greater in the VTA and RRF than in the SNpc (P<0.05 and P<0.001, respectively).

The volume of the nucleoli of TH-AgNOR-positive cells was decreased on the ipsilateral side compared to the contralateral side in the SNpc (−22%), VTA (−24%), and RRF (−26%) (P<0.05). There was no significant difference between the percent decreases in nucleolar volume among the regions.

3. Discussion

This study determined the effects of a unilateral intrastriatal administration of 6-OHDA, which causes oxidative stress-induced neurodegeneration when taken into the cells by the monoamine transporter (Kostrzewa and Jacobowitz, 1974), on dopaminergic neuron number and morphology in the SNpc, VTA, and RRF in rats. The dose of 6-OHDA used was selected to produce a partial lesion, thus modeling the early stages of Parkinson’s disease (Bethel-Brown et al., 2010), and unilateral administration models the initially-unilateral presentation of PD (Hoehn and Yahr, 1967). The effects of the lesion were assessed 14 days after lesion, when the neurodegeneration induced by the toxin is near maximal (Tieu, 2011). Thus, the present study is an examination of dopaminergic cells remaining after a partial lesion. The data show that these brain regions exhibit differential responses to the intrastriatal administration of the toxin with respect to the resulting reduction in regional volume, neuron number, cell density and neuronal volume.

3.1. Effects on regional volume and neuronal number and density

The percentage of SNpc neurons lost in this study (46%) is comparable to others’ findings in moderate PD models (Lee et al., 1996; Rodríguez et al., 2001). As would be anticipated based on the larger number of projections to the striatum from the SNpc (German et al., 1988; Jimenez-Castellanos and Graybiel, 1987) and the intrastriatal route of toxin administration, the SNpc exhibited greater decreases in regional volume, neuron number and neuron density than the VTA and RRF. Nevertheless, in both this and in another study of unilateral intrastriatal 6-OHDA (8 μg) lesions in rats (Gomide et al., 2005), significant loss of cells in the VTA was observed consistent with the presence of dopaminergic projections from the VTA to the caudate-putamen, and reflective of their loss in PD and PD models (German et al., 1988; German et al., 1989; German et al., 1996; Jimenez-Castellanos and Graybiel, 1987; Uhl et al., 1985). Likewise, the dopaminergic cell loss in the RRF observed in this study supports the previous detection of dopaminergic projections from that region to the striatum and their destruction in PD (German et al., 1989; Jimenez-Castellanos and Graybiel, 1987; Rodríguez et al., 2001).

The pattern of dopamine cell loss induced by 6-OHDA is qualitatively similar to the losses reported in post-mortem PD brains. For example, in agreement with the present findings, decreased regional volume and dopaminergic neuronal density in the SN and the VTA were reported in PD (German and Manaye, 1993; Jellinger, 1991; Kashihara et al., 2011; McRitchie et al., 1997; Ziegler et al., 2013). However, most post-mortem studies of PD have examined an advanced stage of neuronal loss in which SNpc neurons are decreased by 70% or more (Hirsch et al., 1988). In PD, neuronal loss from the VTA, which projects chiefly to limbic and cortical brain regions (Oades and Halliday, 1987; van Domburg and ten Donkelaar, 1991), is similar to that in the RRF, but less than in the SNpc (German et al., 1988; German et al., 1996; Hirsch et al., 1988; Hirsch, 1994; Rodríguez et al., 2001; Uhl et al., 1985). Interestingly, in PD as well as in animal models of the disease with extensive dopaminergic cell loss, the ultimate level of neuronal loss in the VTA and RRF peaks at around 70% for the RRF neurons, and at around 60% for the VTA neurons in most studies (German et al., 1988; German et al., 1996; Hirsch et al., 1988; Rodríguez et al., 2001; Uhl et al., 1985). In contrast, in this study of a partial lesion designed to early-stage PD, significant loss of dopaminergic cells was observed in the VTA and RRF; however, the magnitude of cell loss in these regions was roughly 60% of that observed in the SNpc. Interestingly, although the number of dopaminergic cells was decreased in the RRF in PD, RRF regional volume and neuronal density were unaltered in PD (German and Manaye, 1993; Jellinger, 1991; McRitchie et al., 1997), similar to lack of change in neuronal density in the RRF observed in this study. It must be noted, however, that rodents have a lower proportion of dopaminergic neurons in the SN than the VTA compared to primates, while the proportions of RRF neurons are similar (German and Manaye, 1993). Accordingly, susceptibility to PD-modeling lesions may differ between species. Nevertheless, the consistencies in the vulnerability of the SNpc, VTA and RRF regions between rodents and primates underscores the value of rodent models in the study of the early mechanisms of PD disease.

3.2. Effects on neuronal volume

Altered neuronal volume is associated with neurodegeneration (Iacono et al., 2008; Rudow et al., 2008). Neuronal hypertrophy may occur as an initial compensatory reaction to stress, followed by atrophy as the insult overwhelms the cell’s ability to function, ultimately resulting in degeneration (Rudow et al., 2008). Thus, changes in neuron size can be a sign of cellular dysfunction (Janson et al., 1991; Rudow et al., 2008; Smith et al., 1999). In this study, intrastriatal 6-OHDA resulted in decreases in dopaminergic neuronal volume in all regions examined, with greater decreases in volume in the VTA and RRF than in the SNpc. That the SNpc neurons in this study were relatively resistant to change in neuronal volume compared to those of the VTA and RRF is especially intriguing when considered in the context of the greater SNpc dopaminergic neuron loss compared to the VTA and RRF. This may indicate that the ipsilateral RRF and VTA neurons are either more susceptible to decreased volume in early stages of the disease, or that there is relatively greater hypertrophy on the contralateral side, either of which could be indicators that these dopamine subpopulations may play an important role in the early disease process. Alternatively, the ipsilateral SNpc neurons could be relatively hypertrophied in comparison to those of the VTA and RRF in order to compensate for the greater degree of neuronal loss in the SNpc. Accordingly, in future studies, it would be interesting to compare neuronal morphology between lesioned and unlesioned rats. However, a stereological study comparing unilateral intrastriatal 6-OHDA (8μg) and solvent-injected control animals found no difference in contralateral TH-positive SNpc soma volumes between the 6-OHDA- and solvent-injected animals (Gomide et al., 2005), suggesting that such compensatory changes, if any, are minimal.

Post-mortem findings on neuronal volume in PD have been mixed (Rudow et al., 2008). However, a recent study using stereological analysis have found that neuronal volume is decreased in the SN of PD subjects, in clear contrast with the hypertrophy of SNpc neurons found in normal aging (Rudow et al., 2008). In the VTA, dopaminergic neuronal size was decreased in PD (McRitchie et al., 1997), as well as in a mouse chronic MPTP and probenecid model of PD (Ahmad et al., 2009). Furthermore, in the chronic MPTP and probenecid model, the decrease in VTA neuronal volume was restored after 18 weeks of exercise, indicating that the morphology of VTA neurons is an effective indicator of neuronal response to neuroprotective treatments (Ahmad et al., 2009). In the RRF, studies of neuronal volume are lacking, but decreased RRF neuronal diameter was observed after intraventricular 6-OHDA in rats (Rodríguez et al., 2001). A limitation of all of these studies, however, is the inability to determine whether the decrease in neuronal volume is due to neuronal atrophy or to preferential loss of larger neurons, which must be determined in future studies.

3.3. Effects on nucleolar volume

In addition to the changes to neuronal volume, the 6-OHDA lesion resulted in a decrease in nucleolar volume (22–26%) that was similar in all three dopaminergic cell populations. A 16% decrease in nucleolar volume has also been observed in postmortem PD brains (Mann and Yates, 1982). Although studies on the effects of PD on nucleolar volume in the VTA and RRF are lacking, it is interesting that in the present study the nucleolar volume is decreased in both the VTA and the RRF, suggesting that alterations in nucleolar morphology in these regions may also be present in PD. The nucleolus plays an important role in the cellular response to the oxidative stressors implicated in PD, and it is likely that morphological changes to the nucleolus of the surviving neurons reflect the presence of neurodegeneration (Boulon et al., 2010; Hetman and Pietrzak, 2012). The similarity in the effect of 6-OHDA in all three dopaminergic regions suggests that all of these neuronal populations are responding similarly to the toxic insult, at least with respect to its effects on the nucleolus.

3.4. Conclusions

The present findings demonstrate that dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc, VTA, and RRF are affected by a partial unilateral intrastriatal 6-OHDA lesion designed to model early PD. Limitations in experimental throughput restricted this study to the examination of a single dose of 6-OHDA at a single time point after administration, thus limiting interpretation of the results to the effects on surviving neurons, rather than changes occurring during the process of degeneration. Nevertheless, these findings could indicate that although the VTA and RRF may ultimately lose fewer neurons in end-stage PD compared to the SNpc, the VTA and RRF may be more sensitive to early loss of neurons. Moreover, dopaminergic projections from the VTA and RRF play roles in mood and sleep regulation, which are disturbed in early PD, supporting contribution of the loss of neurons from these cell groups in the early phases of the disease (Becker et al., 2002; Claassen et al., 2010). Elucidation of these alterations in morphology is an important step in determining the effects of a degeneration-causing insult, which can then be further explored with biochemical and functional assessments to determine the mechanisms of change and their functional consequences. Finally, although the effects of this lesion on cell number are greatest in the SNpc, all three regions exhibited similar changes in nucleolar morphology, suggesting a similar cellular response to the toxin in all three dopaminergic cell populations, at least with respect to effects on this organelle, and supporting the role of neurodegeneration in regions such as the VTA and RRF in the early neuropathology of PD.

4. Experimental Procedure

All experiments were performed in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Animals and were approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Care and Use Committee.

4.1. Animals, 6-OHDA lesion procedures and lesion validation

Male Long-Evans rats (90–100 days old, n=10; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled facility with a 14–10 hour light-dark cycle (on at 06:00 h) with ad libitum access to standard lab chow (Teklad 8604, Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) and water. Rats were group housed until the lesion surgery, after which they were housed individually.

As previously described in detail (Healy-Stoffel et al., 2012), rats were given single-site unilateral intrastriatal microinjections of 6-OHDA (12.5 μg in 5 μl). Lesions were validated on the basis of d-amphetamine-stimulated rotation (2.5 mg/kg, sc) assessed 7 days after administration of 6-OHDA. Rats were euthanized by transcardial perfusion under pentobarbital anesthesia 7 days after validation of the lesions. Brains were then extracted, cryoprotected and post-fixed.

4.2. Histological analysis

Coronal sections (50 μm) were stained with a modified tyrosine hydroxylase-silver nucleolar (TH-AgNOR) stain using MultiBrain® Technology (NeuroScience Associates, Knoxville, TN) as previously described (Switzer III et al., 2011). This procedure stains the nucleolus of tyrosine-hydroxylase-positive neurons, thus facilitating both stereological cell counting and assessment of nucleolar morphology (Healy-Stoffel et al., 2013). The antibody was rabbit polyclonal anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (Pel-Freez Biologicals, Rogers, AR; P40101-0, Lot# 06432; working dilution 1:1000), which was generated using SDS-denatured tyrosine hydroxylase purified from rat pheochromocytoma. The antibody was specific for a 60 kDa band on Western blots of rat striatal lysates (Haycock, 1989). The immunostaining pattern observed was also consistent with the reported distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase and its mRNA in rat brain (Chan and Sawchenko, 1998).

Every sixth section containing the regions of interest was selected for stereological quantitation (Bregma −4.70 mm to −7.04 mm). TH-AgNOR-stained cells were quantified using the Microbrightfield Stereoinvestigator software package combined with a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U microscope coupled to a Heidenhein linear encoder unit and a QImaging Retiga-2000R color digital video camera.

Using a rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 1998), the borders of the SNpc (Bregma −4.80 mm to −6.30 mm) were carefully outlined in rostrocaudal sections at 4X magnification to exclude the pars reticulata, pars lateralis, pars medialis, and the VTA. The VTA was outlined (Bregma −5.20 mm to −6.80 mm) to exclude the SNpc, SN medialis, fasciculus retroflexus, mammillotegmental tract, mammillary peduncle, interfascicular nucleus, the rostral line of the nucleus of Raphe, the medial lemniscus, the paranigral nucleus, the visual tegmental relay zone, the accessory optic tract, all portions of the interpeduncular nucleus, and the RRF. The parabrachial pigmented nucleus was excluded as much as it was distinguishable from the boundaries of the VTA (which is difficult to determine in the caudal portions). All sections were photographed at low magnification and compared for consistent definition of regions. The RRF was outlined (Bregma −6.30 mm to −7.04 mm) to exclude the SN reticularis and the VTA.

Pilot studies were completed to determine the optimal stereological study parameters for each reference space quantified, and the resultant grid size, counting frame size, and disector height are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Every sixth section containing the regions of interest was counted. Cells were counted and volumes measured at 100X magnification using the simultaneous application of the optical fractionator and a double nucleator method to quantify both the neuronal body and the nucleolar volumes in each neuron. Neurons were counted only when both the soma and the nucleus were present and within focus. The variations in brain positioning in the MultiBrain® embedding process provide a randomized sectioning start for each brain quantified.

Cells were counted using the optical fractionator by placing the disector marker on the nucleolus of the cell. The double nucleator was then employed by automatic software placement of four randomly oriented crossed rays centered at the counting point, and four discriminately placed markers on the outside borders of each of the nucleolus and the outline of the cell body, respectively as previously described in detail (Healy-Stoffel et al., 2013). In some neurons, the nucleolus was visible within the nucleus, but dark staining of the nucleus made it impossible to accurately distinguish the borders of the nucleolus for placement of the nucleator probe (SNpc: 9.8 ± 1.1% on the ipsilateral side and 9.9 ± 0.9% on the contralateral side; VTA: 7.1 ± 1.5% on the ipsilateral side and 10.2 ± 1.4% on the contralateral side; RRF: 9.6 ± 2.1% on the ipsilateral side and 11.2 ± 1.2% on the contralateral side; all not significant by paired t-test). These neurons were included in the total cell count, but were not included in the volumetric analyses of the nucleolus because it was not possible to employ the double nucleator technique.

A maximum coefficient of error of 0.15 (m=1) was accepted for all results, with the exception of the RRF(Gundersen et al., 1999). The RRF is both very small and has relatively fewer neurons than the other regions quantified, thus it was not possible to achieve ideal CE’s within the chosen sampling protocol. Accordingly, in the RRF CE’s ranged from 0.11 to 0.22.

4.3. Data analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. The effects of 6-OHDA between the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres were tested for statistical significance using paired t-tests. Within-subject changes in any parameter were expressed as a percentage relative to the contralateral side. The mean percentage changes among the SNpc, VTA and RRF were compared by repeated-measures one-way ANOVA, and post hoc comparisons were made using Student-Newman-Keuls. In the cases of neuronal number and neuronal volume, where the data were not normally distributed, nonparametric repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used (Instat, v.3.0).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Rats were subjected to a partial unilateral intrastriatal 6-OHDA lesions.

TH-AgNOR-stained neurons were assessed using stereological methods.

Loss of neurons differed between regions: SNpc > VTA ~ RRF.

The decrease in neuron volume differed between regions: VTA ~ RRF > SNpc.

The decrease in nucleolar volume was similarly in all three regions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Robert Switzer III and Stan Benkovic of NeuroScience Associates for preparing the AgNOR stained sections and facilitating our use of this staining technique in this study; and Heather Spalding for expert editorial assistance. Supported by NIH Grants NS067422 (BL), RR016475 (BL), HD02528 (BL, JAS), the University of Kansas Medical Center Research Institute Lied Endowment (BL), the Institute for Advancing Medical Innovation (MH-S), the Mabel A. Woodyard Fellowship in Neurodegenerative Disorders (MH-S), the University of Kansas Endowment (MH-S), and the University of Kansas Medical Center Institute for Neurological Discoveries (MH-S).

Abbreviations

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

- SNpc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

- RRF

and retrorubral field

- TH-AgNOR

tyrosine hydroxylase-silver nucleolar

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Michelle Healy-Stoffel, Email: mstoffel@kumc.edu.

S. Omar Ahmad, Email: sahmad13@slu.edu.

John A. Stanford, Email: jstanford@kumc.edu.

Beth Levant, Email: blevant@kumc.edu.

References

- Ahmad SO, Park JH, Stenho-Bittel L, Lau YS. Effects of endurance exercise on ventral tegmental area neurons in the chronic 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine and probenecid-treated mice. Neurosci Lett. 2009;450:102–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G, Müller A, Braune S, Büttner T, Benecke R, Greulich W, Klein W, Mark G, Rieke J, Thümler R. Early diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2002;249(Suppl 3):III/40–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-1309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethel-Brown CS, Zhang H, Fowler SC, Chertoff ME, Watson GS, Stanford JA. Within-session analysis of amphetamine-elicited rotation behavior reveals differences between young adult and middle-aged F344/BN rats with partial unilateral striatal dopamine depletion. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;96:423–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulon S, Westman BJ, Hutten S, Boisvert FM, Lamond AI. The nucleolus under stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:216–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RK, Sawchenko PE. Differential time- and dose-related effects of haemorrhage on tyrosine hydroxylase and neuropeptide Y mRNA expression in medullary catecholamine neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:3747–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claassen DO, Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, Silber MH, Tippmann-Peikert M, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder preceding other aspects of synucleinopathies by up to half a century. Neurology. 2010;75:494–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ec7fac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutch AY, Elsworth JD, Goldstein M, Fuxe K, Redmond DE, Sladek JR, Roth RH. Preferential vulnerability of A8 dopamine neurons in the primate to the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. Neurosci Lett. 1986;68:51–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein DI, Stanic D, Parish CL, Tomas D, Dickson K, Horne MK. Axonal sprouting following lesions of the rat substantia nigra. Neuroscience. 2000;97:99–112. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German DC, Dubach M, Askari S, Speciale SG, Bowden DM. 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced parkinsonian syndrome in Macaca fascicularis: which midbrain dopaminergic neurons are lost? Neuroscience. 1988;24:161–74. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German DC, Manaye K, Smith WK, Woodward DJ, Saper CB. Midbrain dopaminergic cell loss in Parkinson’s disease: computer visualization. Ann Neurol. 1989;26:507–14. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German DC, Manaye KF, Sonsalla PK, Brooks BA. Midbrain dopaminergic cell loss in Parkinson’s disease and MPTP-induced parkinsonism: sparing of calbindin-D28k-containing cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;648:42–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb24523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German DC, Manaye KF. Midbrain dopaminergic neurons (nuclei A8, A9, and A10): three-dimensional reconstruction in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;331:297–309. doi: 10.1002/cne.903310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German DC, Nelson EL, Liang CL, Speciale SG, Sinton CM, Sonsalla PK. The neurotoxin MPTP causes degeneration of specific nucleus A8, A9 and A10 dopaminergic neurons in the mouse. Neurodegeneration. 1996;5:299–312. doi: 10.1006/neur.1996.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomide V, Bibancos T, Chadi G. Dopamine cell morphology and glial cell hypertrophy and process branching in the nigrostriatal system after striatal 6-OHDA analyzed by specific sterological tools. Int J Neurosci. 2005;115:557–82. doi: 10.1080/00207450590521118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJ, Jensen EB, Kiêu K, Nielsen J. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology--reconsidered. J Microsc. 1999;193:199–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1999.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycock JW. Quantitation of tyrosine hydroxylase, protein levels: spot immunolabeling with an affinity-purified antibody. Anal Biochem. 1989;181:259–66. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy-Stoffel M, Ahmad SO, Stanford JA, Levant B. A novel use of combined tyrosine hydroxylase and silver nucleolar staining to determine the effects of a unilateral intrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine lesion in the substantia nigra: A stereological study. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;210:187–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy-Stoffel M, Ahmad SO, Stanford JA, Levant B. Altered nucleolar morphology in substantia nigra dopamine neurons following 6-hydroxydopamine lesion in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2013;546:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetman M, Pietrzak M. Emerging roles of the neuronal nucleolus. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:305–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E, Graybiel AM, Agid YA. Melanized dopaminergic neurons are differentially susceptible to degeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 1988;334:345–8. doi: 10.1038/334345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch EC, Graybiel AM, Agid Y. Selective vulnerability of pigmented dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1989;126:19–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1989.tb01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch EC. Biochemistry of Parkinson’s disease with special reference to the dopaminergic systems. Mol Neurobiol. 1994;9:135–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02816113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn M, Yahr M. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–42. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono D, O’Brien R, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Pletnikova O, Rudow G, An Y, West MJ, Crain B, Troncoso JC. Neuronal hypertrophy in asymptomatic Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:578–89. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181772794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson AM, Fuxe K, Goldstein M, Deutch AY. Hypertrophy of dopamine neurons in the primate following ventromedial mesencephalic tegmentum lesion. Exp Brain Res. 1991;87:232–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00228526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger KA. Pathology of Parkinson’s disease. Changes other than the nigrostriatal pathway. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1991;14:153–97. doi: 10.1007/BF03159935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Castellanos J, Graybiel AM. Subdivisions of the dopamine-containing A8-A9-A10 complex identified by their differential mesostriatal innervation of striosomes and extrastriosomal matrix. Neuroscience. 1987;23:223–42. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashihara K, Shinya T, Higaki F. Reduction of neuromelanin-positive nigral volume in patients with MSA, PSP and CBD. Intern Med. 2011;50:1683–7. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik D, Rosenblad C, Björklund A. Characterization of behavioral and neurodegenerative changes following partial lesions of the nigrostriatal dopamine system induced by intrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1998;152:259–77. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrzewa RM, Jacobowitz DM. Pharmacological actions of 6-hydroxydopamine. Pharmacol Rev. 1974;26:199–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Sauer H, Bjorklund A. Dopaminergic neuronal degeneration and motor impairments following axon terminal lesion by instrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine in the rat. Neuroscience. 1996;72:641–53. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00571-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann DM, Yates PO. Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:545–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1982.00510210015004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRitchie DA, Cartwright HR, Halliday GM. Specific A10 dopaminergic nuclei in the midbrain degenerate in Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 1997;144:202–13. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oades RD, Halliday GM. Ventral tegmental (A10) system: neurobiology. 1. Anatomy and connectivity. Brain Res. 1987;434:117–65. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(87)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 4. Academic Press; San Diego, California, USA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rieker C, Engblom D, Kreiner G, Domanskyi A, Schober A, Stotz S, Neumann M, Yuan X, Grummt I, Schütz G, Parlato R. Nucleolar disruption in dopaminergic neurons leads to oxidative damage and parkinsonism through repression of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling. J Neurosci. 2011;31:453–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0590-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez M, Barroso-Chinea P, Abdala P, Obeso J, González-Hernández T. Dopamine cell degeneration induced by intraventricular administration of 6-hydroxydopamine in the rat: similarities with cell loss in parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2001;169:163–81. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudow G, O’Brien R, Savonenko AV, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Pletnikova O, Marsh L, Dawson TM, Crain BJ, West MJ, Troncoso JC. Morphometry of the human substantia nigra in ageing and Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:461–70. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0352-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DE, Roberts J, Gage FH, Tuszynski MH. Age-associated neuronal atrophy occurs in the primate brain and is reversible by growth factor gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10893–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Switzer RC, III, Baun J, Tipton B, Segovia C, Ahmad SO, Benkovic SA. Program No. 304.05. 2011 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Vol. 2011. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2011. Modification of AgNOR staining to reveal the nucleolus in thick sections specified for stereological assessment of dopaminergic neurotoxicity in substantia nigra, pars compacta. Online. [Google Scholar]

- Tieu K. A guide to neurotoxic animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a009316. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR, Hedreen JC, Price DL. Parkinson’s disease: loss of neurons from the ventral tegmental area contralateral to therapeutic surgical lesions. Neurology. 1985;35:1215–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.8.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Domburg PH, ten Donkelaar HJ. The human substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area. A neuroanatomical study with notes on aging and aging diseases. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1991;121:1–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler DA, Wonderlick JS, Ashourian P, Hansen LA, Young JC, Murphy AJ, Koppuzha CK, Growdon JH, Corkin S. Substantia nigra volume loss before basal forebrain degeneration in early Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:241–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.